Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teleconsultations (TC) have been increasingly used in cancer care as an alternative to outpatient visits. We aimed to examine patient-related and cancer-specific characteristics associated with experiences with TC among patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methods

This population-based survey included patients with breast, lung, gastrointestinal, urological, and gynaecological cancers with appointments in the outpatient clinics, Department of Clinical Oncology and Palliative Care, Zealand University Hospital, Denmark in March and April 2020. Age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to study associations of sociodemographics, cancer and general health, anxiety, and health literacy with patients’ experiences of TC in regards to being comfortable with TC, confident that the doctor could provide information or assess symptoms/side effects and the perceived outcome of TC.

Results

Of the 2119 patients with cancer receiving the electronic survey, 1160 (55%) participated. Two thirds of patients (68%) had consultations with a doctor changed to TC. Being male, aged 65–79 years, and having TC for test results were statistically significantly associated with more comfort, confidence, and perceived better outcome of TC. Having breast cancer, anxiety, low health literacy, or TC for a follow-up consultation were statistically significantly associated with less positive experiences with TC. Living alone, short education, disability pension, and comorbidity were statistically significantly associated with anxiety and low health literacy.

Conclusions

Most patients reported positive experiences with TC, but in particular patients with anxiety and low health literacy, who were also the patients with fewest socioeconomic and health resources, felt less comfortable and confident with and were more likely to perceive the outcome negatively from this form of consultation. TC may be suitable for increasing integration into standard cancer care but it should be carefully planned to meet patients’ different information needs in order not to increase social inequality in cancer.

Background

To limit the outbreak of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in society, governments worldwide have imposed confinement rules and restrictions on social distancing. Patients with cancer are especially susceptible to infections [Citation1] and seem to be at higher risk of developing serious complications to COVID-19, such as hospitalisations, need for intensive care, and even death [Citation2–5]. Therefore, cancer care was changed as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic with, e.g., teleconsultations (TC) replacing in-person consultations where possible [Citation6]. Only little information exists on cancer patients’ perspectives on TC during the COVID-19 pandemic but some evidence supports positive experiences. In a German study, a considerable proportion of patients with urological cancer who were eligible for TC wished to have such an appointment (86%) [Citation7]. In Houston, Texas, surveys showed high satisfaction of TC in cancer patients (93%) and to some degree also in doctors (65%) [Citation8]. In a Dutch survey, 39% of cancer patients who had been changed to TC were willing to have a TC again [Citation9]. However, modifications of cancer care in general and concerns of not being able to visit their doctor due to COVID-19 restrictions were also seen as independent predictors of anxiety in a survey with cancer patients from 16 European countries [Citation10]. Further, the level of health literacy, defined as a person’s ability to obtain, process, and understand health information to make appropriate health decisions, is important for communication with health care professionals (HCP) and adherence to cancer treatment [Citation11]. Therefore, both anxiety and health literacy may influence patient perceptions of and adherence to care during the COVID-19 restrictions.

In Denmark, cancer care is tax-financed and provided free of charge to all patients. Across the country, departments of oncology to various degrees changed how cancer care were provided during the COVID-19 pandemic, including conversion from in-person outpatient visits to TC. The aim of this population-based study was to examine patient-related and cancer-specific characteristics associated with patients’ experiences of comfort, confidence, and perceived outcome of TC.

Material and methods

Design and participants

This cross-sectional population-based study included patients with cancer from the outpatient clinics, Department of Clinical Oncology and Palliative Care, Zealand University Hospital, Denmark. The department provides all oncological care in the Region Zealand of about 0.8 million inhabitants. As a response to COVID-19, as many outpatient appointments as possible were changed to TC from 15 March 2020. Exceptions to this strategy included consultations for newly diagnosed patients, if palpation of the tumour was necessary or other situations where the doctor decided that an in-person visit was warranted. As the department only offers video consultations on experimental basis, the large majority of TC were by telephone.

All patients with breast, lung, gastrointestinal, urological, and gynaecological cancers who had at least one doctor’s appointment in the outpatient clinics between 15 March and 30 April 2020 were identified from the hospital’s electronic outpatient lists. Between 24 June and 17 July 2020, an invitation letter with information on the study and a SurveyXact link to the questionnaire was sent electronically to all patients from this outpatient list who had a validated ‘e-Boks’ (a secure digital mail box linked to the Danish personal identification [CPR] number). Automatic reminders were sent out twice. The invitation letter invited participants who could not fill out the questionnaire electronically to provide their response orally by telephone.

Participants gave their informed consent by filling out the electronic questionnaire. The study was registered by the Region Zealand Data Protection Agency (number REG-076-2020). The study did not require Ethics Committee approval. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire contained study-specific questions about patient-related characteristics (age, sex, cohabitation status, children, education, work market affiliation, chronic somatic/psychiatric diseases, distance, and transport time to hospital) and cancer-specific characteristics (cancer type, current cancer treatment, and phase in the cancer trajectory). Further, questions were included about patients’ satisfaction and experiences of comfort and confidence with TC focusing on the latest TC with a doctor from the department. Symptoms of anxiety were assessed on the generalised anxiety disorder 7 scale (GAD-7), which is comprised seven items with response options ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the days’, ‘nearly every day’, and a summary score ranging from 0 to 21 with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms [Citation12]. We applied scores of 5, 10, and 15 as cutoff points for mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of anxiety, respectively [Citation13]. Health literacy was assessed on the Health Literacy Questionnaire subscale 6 ‘ability to actively engage with HCP’ and subscale 9 ‘understand health information enough to know what to do’. Each subscale had five items with response options ‘cannot do’, ‘very difficult’, ‘quite difficult’, ‘quite easy’, and ‘very easy’. A higher summary score indicated higher health literacy [Citation14,Citation15]. Scores were dichotomised into low versus high health literacy on both subscales using the cutoff score 4.0, which was the median score of both a Danish population [Citation14] and our sample.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the distribution of patients’ characteristics. Logistic regression analyses were performed to examine associations between patient-related and cancer specific variables (sex, age, cohabitation status, children, education, work market affiliation, cancer type, cancer trajectory, comorbidity, symptoms of anxiety, health literacy, transport, and distance to hospital) and the binary outcomes: 1) consultations changed to TC (yes vs. no); 2) patient experiences of being comfortable with TC (yes to a high degree/yes to some degree) vs. less comfortable with TC (to a lesser degree/not at all); 3) patients’ experiences of being confident (yes to a high degree/yes to some degree) vs. less confident (to a lesser degree/not at all) that the doctor could provide information or assess symptoms/side effects by TC, respectively; 4) patients’ perceived outcome of TC measured as having a positive (very satisfied/satisfied) vs. neutral/negative (neutral/unsatisfied/very unsatisfied) overall experience; 5) symptoms of anxiety (mild/moderate/severe vs. none); and 6) health literacy (low vs. high). Analyses were adjusted for the confounders age and sex with exception of cancer type, which was only adjusted for age. We did no further adjustments as the purpose of the study was to describe associations and risk groups among patients. In order to examine if sex was an effect modifier, we performed the regression analyses of experiences with TC stratified by men and women. Associations were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. The few missing values (education n = 1, work market affiliation n = 1) were omitted from the analyses. All analyses were performed in RStudio Statistical Package version 1.4.110 for Windows 6 (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Descriptive characteristics

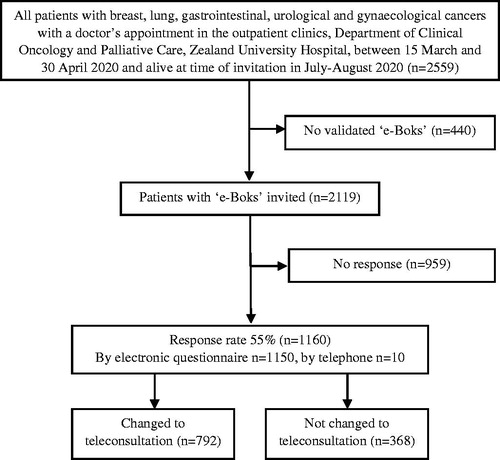

The response rate was 55% with 1160 of the 2119 invited patients completing the questionnaire (). Participants were relatively similar in terms of cancer diagnosis, sex, and age compared to non-participants, but patients without ‘e-Boks’ were older across all cancer diagnoses (Supplementary File A). The median age of the 1160 patients was 68 years (range 29–91 years). The majority were female (71%), living with a partner (74%), having vocational education (32%), and retired (58%). Most patients had breast cancer (47%) followed by lung cancer (20%) and were in follow-up or treatment (47% and 45%, respectively) (). Two thirds of patients (68%) reported having been changed to TC with a median of 2 TC per patient (ranges 1–12), 99% by telephone, and 1% by video. Patients in follow-up had higher odds of a change to TC compared to patients in treatment (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.79–3.07) (Supplementary File B).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 1160 patients with cancer – stratified by changed to teleconsultation (TC) or not changed to TC during the COVID-19 pandemic.

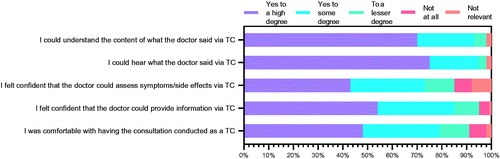

Among the 792 patients with TC, the majority understood the content (93%), could hear what the doctor said (95%), and felt comfortable and confident with TC (73–85%) to a high/some degree (). Few patients postponed or cancelled appointments or reported having omitted to contact the department with questions that they would normally ask (both 5%) (data not shown).

Patients’ experiences with TC

Male patients were more comfortable with TC (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.17–3.04) and more confident that symptoms/side effects could be assessed (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.06–2.75) compared to females. Findings of similar statistically significant ORs were observed for being comfortable, confident, and having perceived better outcome of TC in patients aged 65–79 compared to aged 50–64 years. Overall, patients with other cancer diagnoses were more comfortable and confident compared to patients with breast cancer, although only statistically significant for patients with lung and urological cancers in relation to being comfortable with TC (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.19–3.27 and OR 3.21, 95% CI 1.45–7.12, respectively) and confident that the doctor could provide information (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.06–3.37 and OR 4.41, 95% CI 1.51–12.89, respectively). Similar statistically significant associations were seen for patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancers for confidence of the doctor’s symptoms/side effect assessment. Patients who had TC for blood test results were more comfortable with TC (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.10–3.08), confident that the doctor could assess symptoms/side effects (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.06–2.94) and more had a positive perceived outcome of TC (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.04–2.29) compared to patients who received TC for another reason than blood test results. Similar statistically significant ORs were observed if the purpose of TC was results of scan/biopsy/surgery. Having a TC for follow-up was, however, inversely associated with being comfortable with TC (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36–0.77) and confident with TC (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.25–0.61 for the doctor’s information, OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.32–0.69 for symptoms/side effects, respectively). Similarly, having mild or moderate/severe anxiety or low health literacy were statistically significantly associated with being less comfortable and confident with TC, and reduced likelihood of having a positive perceived outcome of TC in all observed ORs compared to having no anxiety or high health literacy, respectively. We investigated if sex was an effect modifier. However, the point estimates differed only slightly by sex and in no systematic way that could change the results or conclusions (data not shown) ().

Table 2. Age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for experiences of comfort, confidence, and perceived outcome of teleconsultations among 792 cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anxiety and health literacy

In regards to having mild/moderate/severe symptoms of anxiety, ORs were increased among patients on disability pension (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.48–4.02), age retirement (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.06–2.80), having comorbidity (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.00–2.09 for 1 and OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.66–3.30 for +2, respectively), low ability to engage with HCP (OR 2.94, 95% CI 2.21-3.90) and low understanding of health information (OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.74–3.34). Likewise, disability pension (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.04–2.79) or having anxiety (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.82–3.50 for mild anxiety and OR 4.07, 95% CI 2.63–6.30 for moderate/severe anxiety, respectively) were associated with low ability to engage with HCP. Finally, ORs for low ability to understand health information were increased for patients living alone (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.03–2.02), having a short or medium education (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.55–3.55 and OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.35–2.80, respectively), and for those who received disability pension (OR 4.12, 95% CI 2.33–7.27). Similar statistically significantly increased ORs were seen for patients with lung cancer, who were not in treatment, who had +2 comorbidities, anxiety, and were living ≥ 80 km from the hospital ().

Table 3. Age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for having anxiety or low health literacy among 1160 patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

In this population-based survey, two-thirds of the responding cancer patients had consultations with a doctor replaced by TC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients in follow-up care were more likely to be changed to TC compared to patients in treatment. Despite what may have been feared, few patients cancelled or postponed appointments themselves or were reluctant to contact the department. Overall, most patients reported positive experiences with TC. These findings confirm previous studies reporting satisfaction with TC among patients and HCP during the cancer care trajectory both before [Citation16–18] and during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation7–9]. Still, having breast cancer or being in follow-up were characteristics associated with less positive experiences with TC. Further, particularly patients having symptoms of anxiety or low health literacy were less comfortable and confident with TC pointing towards potential barriers to optimal outcome of TC among these subgroups of patients. Living alone, short education, disability pension, and comorbidity were associated with having anxiety and low health literacy, which is in line with prior findings of low socioeconomic position associated with increased anxiety [Citation19] and low health literacy [Citation20] in cancer patients. Thus, patients least comfortable and confident with TC were patients with the fewest socioeconomic or health resources. Almost 3 out of 10 patients reported a potentially clinical level of anxiety in our sample. Moderate/severe anxiety was reported by 9% corresponding to 10% in oncological, haematological and palliative care settings reported in a meta-analysis of psychiatrically validated mood disorders in cancer patients [Citation21]. That as many as 19% reported mild clinical anxiety may, however, be related in parts to COVID-19. Likewise, low health literacy has been associated with difficulty understanding government messaging of COVID-19 related restrictions [Citation22]. While it is not surprising that the COVID-19 related changes to the clinical cancer care may increase level of anxiety, an important finding is that patients with low health literacy may be particularly anxious about juggling COVID-19 restrictions in the specialised cancer setting.

Having had TC for blood test results was associated with reporting more positive experiences with TC perhaps as some patients might be familiar with receiving blood test results by telephone. Results of scan/biopsy/surgery were borderline significant, which could reflect diverging attitudes depending on positive or negative messages. Having a TC for follow-up was associated with less positive experiences, possibly due to less frequent outpatient visits and a higher need of face-to-face contact with HCP among these patients. Since experiences with TC were dependent on particularly patient-related characteristics in both our study and previous research [Citation23], TC during cancer treatment and follow-up care may be suitable for some patients but should not be considered a ‘one-fits-all’ approach. Failure to meet patients’ different information needs could potentially increase social inequality in cancer.

Strengths and limitations

Of notable strengths were that our study included a large sample representing various cancer types across the cancer care trajectory and a wide age span with 61% being aged 65–91 years. However, the study excluded patients without ‘e-Boks’, who were older across all cancer diagnoses and thereby reducing generalisability of our findings. It remains, however, uncertain in which direction the inclusion of patients without ‘e-Boks’ would change the results. Further, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes any interpretation of direction in associations analysed. Since the patients were asked to focus on their latest TC with a doctor, our findings could be susceptible to both loss of more nuanced information and recall bias as it may have been difficult for patients to distinguish between past consultations. As a cross-sectional study, we cannot compare satisfaction with consultations before the COVID-19 pandemic and also not with those who did not have TC since patients receiving in-person consultations were highly selected. Lastly, since the department offers consultations by video solely on experimental basis, our findings only represent experiences with TC by telephone. Furthermore, the patients’ experiences with TC represent the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic only, where most of the patients and HCP were not acquainted with using TC in daily clinical practice as these were only used occasionally to communicate blood test results. Our study described how the patients experienced TC, but high patient satisfaction does not necessarily mean high clinical quality. It is important to supplement this study with studies of clinical quality to see whether the same results can be achieved regardless of cancer type.

Conclusion

Most cancer patients reported positive experiences with having consultations replaced by TC during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings offer important opportunities for telephone contacts to some patients during cancer care, also beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly patients with symptoms of anxiety and low health literacy felt less comfortable and confident with TC, and bearing in mind that low socioeconomic position was consistently associated with anxiety and low health literacy, the implementation of TC should be carefully planned to meet patients’ different information needs in order not to increase social inequality in cancer.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.3 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncology. 2020;25(6):e936–e945.

- Lièvre A, Turpin A, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Risk factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality among solid cancer patients and impact of the disease on anticancer treatment: a French nationwide cohort study (GCO-002 CACOVID-19). Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:62–81.

- de Joode K, Dumoulin DW, Tol J, et al. Dutch oncology COVID-19 consortium: outcome of COVID-19 in patients with cancer in a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:171–184.

- Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1108–1110.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337.

- Elkaddoum R, Haddad FG, Eid R, et al. Telemedicine for cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic: between threats and opportunities. Future Oncol. 2020;16(18):1225–1227.

- Boehm K, Ziewers S, Brandt MP, et al. Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic-potential, risk factors, and patients’ perspective. Eur Urol. 2020;78(1):16–20.

- Darcourt JG, Aparicio K, Dorsey PM, et al. Analysis of the implementation of telehealth visits for care of patients with cancer in Houston during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Oncol Oncol Practice. 2020;17:e36–e43.

- van de Poll-Franse LV, de Rooij BH, Horevoorts NJE, et al. Perceived care and well-being of patients with cancer and matched norm participants in the COVID-19 crisis: results of a survey of participants in the Dutch PROFILES registry. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):279–284.

- Gultekin M, Ak S, Ayhan A, et al. Perspectives, fears and expectations of patients with gynaecological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Pan-European study of the European Network of Gynaecological Cancer Advocacy Groups (ENGAGe). Cancer Med. 2021;10(1):208–219.

- Koay K, Schofield P, Jefford M. Importance of health literacy in oncology. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8(1):14–23.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Rutter LA, Brown TA. Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 (GAD-7) in outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2017;39(1):140–146.

- Maindal HT, Kayser L, Norgaard O, et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ): robust nine-dimension Danish language confirmatory factor model. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1232.

- Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, et al. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):658.

- Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540–545.

- Barsom EZ, Jansen M, Tanis PJ, et al. Video consultation during follow up care: effect on quality of care and patient- and provider attitude in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(3):1278–1287.

- Steindal SA, Nes AAG, Godskesen TE, et al. Patients’ experiences of telehealth in palliative home care: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e16218.

- Simon AE, Wardle J. Socioeconomic disparities in psychosocial wellbeing in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(4):572–578.

- Bo A, Friis K, Osborne RH, et al. National indicators of health literacy: ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers - a population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1095.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174.

- McCaffery K, Dodd R, Cvejic E, et al. Health literacy and disparities in COVID-19–related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours in Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 2020;30(4):30342012..

- Cox A, Lucas G, Marcu A, et al. Cancer survivors’ experience with Telehealth: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e11.