Abstract

Background

There are little and inconsistent data from clinical practice on time on treatment with the androgen receptor-targeted drugs (ART) abiraterone and enzalutamide in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). We assessed time on treatment with ART and investigated predictors of time on treatment.

Material and methods

Time on treatment with ART in men with mCRPC in the patient-overview prostate cancer (PPC), a subregister of the National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden, was assessed by use of Kaplan–Meier plots and Cox regression. To assess the representativity of PPC for time on treatment, a comparison was made with all men in NPCR who had a filling for ART in the Prescribed Drug Registry.

Results

2038 men in PPC received ART between 2015 and 2019. Median time on treatment in chemo-naïve men was 10.8 (95% confidence interval 9.1–13.1) months for abiraterone and 14.1 (13.5–15.5) for enzalutamide. After the use of docetaxel, time on treatment was 8.2 (6.5–12.4) months for abiraterone and 11.1 (9.8–12.6) for enzalutamide. Predictors of a long time on treatment with ART were long duration of ADT prior to ART, low serum levels of PSA at start of ART, absence of visceral metastasis, good performance status, and no prior use of docetaxel. PPC captured 2522/6337 (40%) of all men in NPCR who had filled a prescription for ART. Based on fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry, men in PPC had a slightly longer median time on treatment with ART compared to all men in NPCR, 9.6 (9.1–10.3) vs. 8.6 (6.3–9.1) months.

Conclusions

Time on treatment in clinical practice was similar or shorter than that in published RCTs, due to older age, poorer performance status and more comorbidities.

Introduction

In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) who in addition to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) received abiraterone or enzalutamide, two androgen receptor-targeted drugs (ART), had longer progression-free and overall survival compared with men treated with ADT [Citation1–4]. The increase in survival was observed both in the chemo-naïve and in the post-docetaxel setting and was longer in chemo-naïve men. As a result, the use of ART in addition to ADT in both settings is now recommended by many guidelines [Citation5]. Given that ART is expensive and that prostate cancer is the most prevalent in many high and intermediate-income countries, the use of ART will have a substantial impact on health care expenditure.

In previous observational studies (S1. Supplementary Table 1) there has been a large variation in the reported time on treatment with ART, for example, the median time on treatment with abiraterone ranged from 4 months in chemo-naïve men to 20 months after chemotherapy [Citation6–22]. In addition, for many studies, time on treatment with ART was investigated as a secondary endpoint, and many of these studies were based on few patients.

We recently investigated time on treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide in 6337 men with mCRPC in The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden by use of fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry with a special emphasis on the effect on time on treatment of the grace period, i.e., time without drug supply between two consecutive fillings [Citation23]. The strength of that study was that it was population-based and included all men on ART in Sweden, but it was limited by a lack of information on the use of chemotherapy, cancer characteristics, and performance status at the start of ART.

The aim of this study was to investigate time on treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide in clinical practice in men with mCRPC both in the chemo-naïve and the post-docetaxel setting and to assess factors associated with time on treatment, including data on the use of chemotherapy, cancer characteristics, and performance status at the start of ART.

Methods

The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden

Since 1998, NPCR captures 98% of all incident cases of prostate cancer (PCa) in Sweden compared to the National Cancer Registry to which reporting is mandated by law. NPCR holds data on cancer characteristics, diagnostic workup, and primary treatment [Citation24]. No registration on follow-up data is made in the primary registration in NPCR.

The Patient-overview Prostate Cancer (PPC)

PPC was created in order to capture longitudinal data for men with advanced PCa in NPCR [Citation25]. Men who start ADT are eligible to be registered in PPC and information is captured from the date of start of ADT to the date of death. For men who started ADT before their registration in PPC, data are retrospectively retrieved from medical charts. PPC includes the date for CRPC diagnosis, the date for start and stops of PCa treatments including chemotherapy and Radium-223 delivered in-hospital, results from imaging and laboratory tests, e.g., serum levels of prostate specific antigen (PSA), and registration of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/World Health Organization Performance Status (ECOG) and electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) at each consultation [Citation26,Citation27].

The Prescribed Drug Registry

Since their approval in 2015, all filled prescriptions for abiraterone (ATC code L02BX03) and enzalutamide (ATC code L02BB04) are registered in The Prescribed Drug Registry [Citation28,Citation29].

The Patient Registry

The In-Patient Registry holds data on diagnoses and procedures with a virtually complete capture. Data on discharge diagnoses in the In-Patient Registry were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on ten years before the start of follow-up [Citation30,Citation31].

The Cause of Death Registry

The Cause of Death Registry was used to retrieve the date and cause of death. Reporting to this Registry is mandated by law and it is made by the treating physician and monitored by staff at The National Board of Health and Welfare.

Study design and study population

The registers described above are held at the National Board of Health and Welfare, and they were linked to NPCR by use of the unique Swedish personal identity number in Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe) [Citation32].

All men who received abiraterone or enzalutamide according to PPC between 1 July 2015 and 31 October 2019 were included in this study (S2. Supplementary Figure 1). We excluded men for whom use of ART had been registered in PPC within 6 months after PCa diagnosis in order to exclude use in men with de novo metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPC). We also excluded men who had received docetaxel upfront for mHSPC, men treated with chemotherapy other than docetaxel before ART, and men treated with Ra-223 before ART. We restricted the analysis to first ART, i.e., men who used abiraterone before enzalutamide were assessed only in the abiraterone group and vice versa. Follow-up ended on 31 October 2019.

In order to compare time on treatment for men registered in PPC vs all men in Sweden who had received ART, we used information on fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry for abiraterone and enzalutamide between 1 July 2015 and 31 October 2019, for all men in NPCR. As in the analysis in PPC, the only use of first ART was analyzed and men who had filled a prescription for ART within 6 months after PCa diagnosis were excluded.

Variable definition and outcome measures

We used data in NPCR on the PCa risk category at diagnosis and primary treatment [Citation24]. The start of ADT was defined by the date for the first filling in the Prescribed Drug Registry for a GnRH agonist or anti-androgen, or date for bilateral orchiectomy in the Patient Registry. Duration of ADT only was calculated from this date until the date for first-line treatment for mCRPC, i.e., date of start of ART in chemo-naïve men and date of the first dose of docetaxel in men who received docetaxel before ART.

Information on metastatic site at ART start was classified as lymph nodes, bone metastasis including concomitant lymph nodes metastasis, and visceral metastases including concomitant metastasis in lymph nodes and/or bones.

Registration in PPC was categorized as prospective, i.e., all data had been entered at the date of each event, or retrospective, i.e., data were extracted from medical charts for events prior to the start of registration in PPC.

Time on treatment with ART in our main analysis was the time between start and stop of treatment in PPC.

Finally, a supporting analysis was performed in order to assess if the time on treatment with ART in PPC was representative of all men on ART in Sweden. For this analysis, which was based on data in the Prescribed Drug Registry, time on treatment was defined as the time between the date of first filling for ART and the date of the end of drug supply. If the date of the end of supply was at a later calendar date than the date of death, the date of death was used as a stop date for ART.

Statistical methods

There were some missing data, for example, for 500/2038 men (24%) data on ECOG at the start of ART was missing and for 271/2038 men (13%) date of treatment stop was missing. Multiple imputations by chained equation (MICE) were used to impute missing data. Twenty datasets with imputed values were constructed by use of imputation models including data on patient and cancer characteristics and on time on treatment from PPC and the Prescribed Drug Registry. Time on treatment based on fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry was included in the models to improve the imputation of missing time on treatment in PPC. Rubin's rule for multiple imputations was used to account for variability between the twenty imputed datasets. Kaplan Meier curves were used to analyze time on treatment and Cox regression analyses were used to investigate the association of putative predictive factors with the risk of drug stop.

Time on treatment with ART based on fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry for men in NPCR and registered in PPC vs. all men in NPCR was analyzed by use of Kaplan–Meier curves. We also assessed time on treatment for men prospectively vs retrospectively registered in PPC.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board in Uppsala, that waived the informed consent requirement.

Results

2038 men were included in the final study set, of whom 603 were treated with abiraterone and 1435 were treated with enzalutamide (). 493/603 men (82%) on abiraterone and 1108/1435 men (77%) on enzalutamide were chemo-naïve. At the date of PCa diagnosis, 392/603 men (65%) on abiraterone and 984/1435 men (69%) on enzalutamide had high-risk, locally advanced, or metastatic disease. Duration of ADT until the addition of first-line CRPC treatment was longer in men who received ART as first-line treatment, i.e., chemo-naïve men, compared to men who received docetaxel as first-line treatment. At ART start, chemo-naïve men were older, had higher median PSA, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index and higher ECOG than men who had received docetaxel prior to ART. Overall, the median follow-up in PPC was 17 months (IQR 9.0–27.9).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in the Patient-overview Prostate Cancer (PPC).

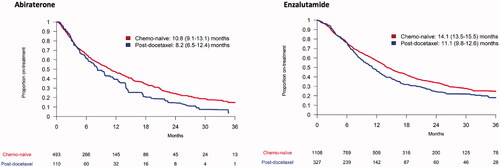

Median time on treatment with ART was longer for chemo-naïve men than for men who had received prior docetaxel (). Time on treatment with abiraterone in chemo-naïve men was 10.8 months (95% confidence interval CI 9.1–13.1) and after docetaxel 8.2 months (6.5–12.4) and for enzalutamide 14.1 months (13.5–15.5) in chemo–naïve men and 11.1 months (9.8–12.6) after docetaxel.

Figure 1. Median (95% confidence interval) time on treatment for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer on abiraterone and enzalutamide in the Patient-overview Prostate Cancer stratified into chemo-naïve and post-docetaxel.

Among chemo-naïve men, long-term response, defined as treatment longer than 36 months, was observed in 15% of men on abiraterone and 25% of men on enzalutamide. After docetaxel use, 18% of men on enzalutamide had a long-term response, whereas there was no man who had a long-term response to abiraterone.

Among chemo-naïve men, non-response, defined as time on treatment shorter than 3 months, was observed in 18% of men on abiraterone and 12% of men on enzalutamide. After docetaxel use, 20% of men on abiraterone and 10% on enzalutamide had a non-response to treatment.

A long time on ADT before first-line treatment for CRPC, low serum levels of PSA, absence of visceral metastasis, good performance status at the start of ART, and no prior docetaxel was associated with a long time on treatment with ART in multivariable analyses (). Age and calendar period at the start of ART was not associated with time on treatment.

Table 2. Risk of stop of treatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide according to cancer characteristics, previous cancer treatment, performance status, comorbidity, age and year at start of androgen receptor-targeted therapy.

The frequency of cause for drug stop was very similar for men on abiraterone and enzalutamide (S1. Supplementary Table 2). The most common cause for drug stop was tumor progression, which occurred in 828/1351 men (61%); 143/1351 men (11%) stopped ART because of side effects, and 25/1351 men (2%) died while on treatment.

Time on treatment with ART was similar in men for whom data had been prospectively or retrospectively collected (S2. Supplementary Figure 2).

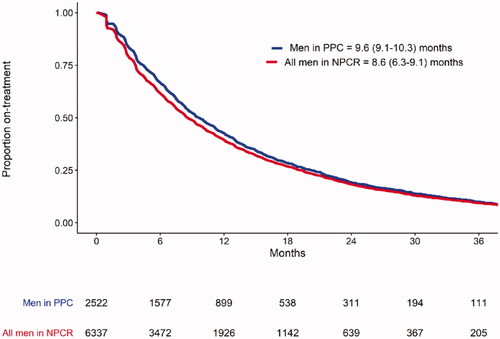

Out of 6337 men registered in NPCR who had filled a prescription for ART, 2522 men (40%) had also been registered in PPC. Based on data on fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry, time on treatment with ART was slightly longer for men in PPC, 9.6 months (95% CI 9.1–10.3) vs 8.6 months (6.3–9.1) for all men in NPCR, (). Baseline characteristics were quite similar in men registered/or not registered in PPC (S1. Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2. Median (95% confidence interval) time on treatment with both ARTs based on fillings in the prescribed drug registry for men in NPCR and registered in PPC vs. all men in NPCR who had filled a prescription for ART. ART: androgen receptor-targeted drugs; NPCR: the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden; PPC: the Patient-overview Prostate Cancer. Abiraterone and enzalutamide were analyzed altogether.

Discussion

In this register-based study of time on treatment with androgen receptor-targeted drugs in men with mCRPC in clinical practice, the median time on treatment for chemo-naïve men with abiraterone was 11 months and with enzalutamide 14 months. Among men who had previously received docetaxel, the median time on treatment with abiraterone was 8 months and with enzalutamide 11 months. No prior use of docetaxel, long time on ADT prior to first-line CRPC treatment, low PSA at start of ART, no visceral metastasis and good performance status were associated with a long time on ART. Roughly 10–20% of men with mCRPC remained on ART for more than three years. Tumor progression was the most common cause for drug stop overall.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is that it was based on the Patient-overview Prostate Cancer which includes comprehensive longitudinal data specifically registered for this purpose by physicians and staff (i.e., not administrative data) on chemotherapy, performance status and cancer characteristics at the start of ART. We also had access to comprehensive high-quality data through linkage with population-based registries [Citation25]. Another strength is that we could compare men in PPC vs virtually all men in Sweden who had a filling for abiraterone or enzalutamide since NPCR captures 98% ofall PCa cases and the Prescribed Drug Registry in Sweden captures virtually all fillings of all drugs. 40% of all men in NPCR with mCRPC treated with abiraterone or enzalutamide were registered in PPC. Time on treatment with ART assessed by fillings in the Prescribed Drug Registry, regardless of the use of other therapies before ART, was slightly longer for men also registered in PPC than for all men in NPCR. There were only minor differences in baseline characteristics between men in PPC and men in NPCR but not in PPC including cancer characteristics at the date of diagnosis, the primary treatment for PCa, and comorbidity, that could explain the small difference in time on treatment. Based on these findings, we argue that results from PPC are representative of the use of these drugs in Sweden.

Limitations of our study include that there were some missing data, in particular for the metastatic site and ECOG performance status for around a quarter of the men in the study. To overcome this limitation, multiple imputations were performed. For almost half of the men data had been retrospectively registered, i.e., extracted from medical charts, and for a large proportion of these men ECOG was missing, however, time on treatment was quite similar in men with prospectively collected data vs. men with retrospectively collected data.

Comparisons with RCTs

In comparison with RCTs on ARTs in the chemo-naïve setting, we found a shorter median time on treatment, 11 months in our study for abiraterone vs 14 months in the COU-AA-302 trial [Citation1], and 14 months in our study for enzalutamide vs. 17 months in the PREVAIL trial (S1. Supplementary Table 4) [Citation2]. These differences are likely caused by the fact that men in our study were older and less healthy than men in these RCTs. For example, the median age at the start for abiraterone was 79 years in our study vs. 71 years in the COU-AA-302 and for enzalutamide 78 years in our study vs. 72 years in the PREVAIL. More than 30% of men in our study had Charlson Comorbidity Index above 2 and 11–16% of men had ECOG performance status above 2, whereas in the RCTs study participants had less comorbidities and all had ECOG 0 or 1. In addition, we found that 9% of chemo-naïve men had visceral metastasis at the start of abiraterone use, while in the COU-AA-302 presence of visceral metastasis was an exclusion criterium.

When ART was used after docetaxel, time on treatment with abiraterone was 8 months in our study, i.e., similar to that in the COU-AA-301 trial [Citation4], and time on treatment with enzalutamide was longer in our study than in the AFFIRM trial, 11 vs. 8 months, respectively [Citation3]. The differences in characteristics between men in our study and men in RCTs on ART use after docetaxel were smaller than those for chemo-naïve men. For example, the difference in median age was smaller between our study and the COU-AA-30 and the AFFIRM, 72 vs. 69 years for abiraterone and 73 vs. 69 years for enzalutamide, respectively. Moreover, in these RCTs, almost 10% of men had ECOG up to 2. Overall, despite that man in our study were older and had a poorer performance status than men in RCTs, time on treatment with ART was quite similar.

Observational studies

Previous observational multi- or single-institution studies have reported a wide range in time on treatment with ART, from 3 to almost 20 months (S1. Supplementary Table 1). Our results are in line with most other large and contemporary studies in which time on treatment for abiraterone or enzalutamide has consistently been longer in chemo-naïve men than in men who had received prior docetaxel. Time on treatment in previous observational studies has been shorter or similar to that in RCTs, with a few exceptions [Citation6–22].

Time on treatment with abiraterone was shorter than with enzalutamide both in chemo-naïve and post-docetaxel settings, which is in line with most of the previous studies [Citation1–4,Citation12,Citation18,Citation20]. The reason for this difference in time on treatment is unknown. RCTs comparing head-to-head abiraterone and enzalutamide are lacking and therefore no conclusions can be drawn on differences in time on treatment or survival outcomes.

Prediction of time on treatment

Long duration of ADT, absence of visceral metastasis, and good performance status were also associated with a long time on treatment in previous studies [Citation13,Citation33,Citation34]. Prediction of time on treatment with ART is useful for clinical decision making and we found that information readily available in clinical practice were quite strong predictors. Better predictive biomarkers are however needed in order to further individualize treatment.

The proportion of long-term response in our study was between 10 and 20% in both the chemo-naïve setting and after docetaxel, which is in line with results obtained in previous studies confirming that few men are treated for very long periods of time [Citation9,Citation10,Citation14,Citation16–18,Citation21]. The proportion of men with no response was around 10–20% and quite similar in the chemo-naïve and the post-docetaxel setting and comparable to the results in RCTs [Citation1–4].

Drug stop

Around 60% of men stopped ART due to tumor progression, whereas other reasons were less common. The next most common reason stopped due to adverse effects, which was a common cause in the first months of treatment. The reasons for drug stops were similar for abiraterone and enzalutamide. In the RCTs, drug stop due to adverse events was above 10% for abiraterone and slightly lower than 10% for enzalutamide. Overall, the proportion of men who stopped treatment due to side effects was low in observational studies based on clinical practice, and in some cases even lower than that reported in RCTs. Thus, ART appeared to have a favorable safety profile for most men in clinical practice, even among men who are considerably frailer than men in RCTs.

Conclusion

In this register-based study of the use of abiraterone and enzalutamide in men with mCRPC, time on treatment was similar or slightly shorter than what has been reported from RCTs, likely due to the fact that men in clinical practice are on average, older, have a lower performance status, and more comorbidities than men included in randomized trials. Our results indicate that the use of these drugs, the proportion of non-responders, long responders, and men who experienced side effects are quite similar in clinical practice to what has been reported in RCTs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (366.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.6 KB)Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR) steering group: Pär Stattin (chair), Ingela Franck Lissbrant (deputy chair), Johan Styrke, Camilla Thellenberg Karlsson, Hampus Nugin, Stefan Carlsson, Marie Hjälm Eriksson, David Robinson, Mats Andén, Ola Bratt, Magnus Törnblom, Johan Stranne, Jonas Hugosson, Maria Nyberg, Olof Akre, Per Fransson, Eva Johansson, Gert Malmberg, Hans Joelsson, Fredrik Sandin, and Karin Hellström.

Disclosure statement

Region Uppsala has, on behalf of NPCR, made agreements on subscriptions for quarterly reports from Patient-overview Prostate Cancer with Astellas, Sanofi, Janssen, and Bayer, as well as research projects with Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138–148.

- Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):424–433.

- Cabot RC, Harris NL, Rosenberg ES, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197.

- Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):983–992.

- Mottet N, Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, et al. EAU – EANM – ESTRO – ESUR – SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer 2020. EAU – EANM – ESTRO – ESUR – SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer [Internet]. Arnhem, The Netherlands; [cited 2020 Jul 12]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/#1

- Alghazali M, Löfgren A, Jørgensen L, et al. A registry-based study evaluating overall survival and treatment duration in Swedish patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with enzalutamide. Scand J Urol. 2019;53(5):312–317.

- Biró K, Budai B, Szőnyi M, et al. Abiraterone acetate + prednisolone treatment beyond prostate specific antigen and radiographic progression in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Urologic Oncol Seminars Orig Investigations. 2018;36(2):81.e1-81–e7.

- Leibowitz-Amit R, Seah J-A, Atenafu EG, et al. Abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a retrospective review of the princess margaret experience of (I) low dose abiraterone and (II) prior ketoconazole. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(14):2399–2407.

- Houédé N, Beuzeboc P, Gourgou S, et al. Abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: long term outcome of the temporary authorization for use programme in France. Bmc Cancer. 2015;15:222.

- Boegemann M, Khaksar S, Bera G, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for the management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) without prior use of chemotherapy: report from a large, international, real-world retrospective cohort study. Bmc Cancer. 2019;19(1):60.

- Pilon D, Behl AS, Ellis LA, et al. Duration of treatment in prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide. JMCP. 2017;23(2):225–235.

- Salem S, Komisarenko M, Timilshina N, et al. Impact of abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide on symptom burden of patients with chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Oncol. 2017;29(9):601–608.

- Azad AA, Eigl BJ, Leibowitz-Amit R, et al. Outcomes with abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients who have poor performance status. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):441–447.

- Verzoni E, Giorgi UD, Derosa L, et al. Predictors of long-term response to abiraterone in patients with metastastic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2016;7(26):40085–40094.

- Ramalingam S, Humeniuk MS, Hu R, et al. Prostate-specific antigen response in black and white patients treated with abiraterone acetate for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(6):418–424.

- Beardo P, Osman I, José BS, et al. Safety and outcomes of new generation hormone-therapy in elderly chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients in the real world. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;82:179–185.

- Harshman LC, Werner L, Tripathi A, et al. The impact of statin use on the efficacy of abiraterone acetate in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2017;77(13):1303–1311.

- Schultz NM, Flanders SC, Wilson S, et al. Treatment duration, healthcare resource utilization, and costs among chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate: a retrospective claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2018;35(10):1639–1655.

- Flaig TW, Potluri RC, Ng Y, et al. Treatment evolution for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with recent introduction of novel agents: retrospective analysis of real-world data. Cancer Med. 2016;5(2):182–191.

- George DJ, Sartor O, Miller K, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in a real-world clinical practice setting in the United States. Clin Genitourin Canc. 2020;18(4):284–294.

- Svensson J, Andersson E, Persson U, et al. Value of treatment in clinical trials versus the real world: the case of abiraterone acetate (zytiga) for postchemotherapy metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients in Sweden. Scand J Urol. 2016;50(4):286–291.

- Lu C, Terbuch A, Dolling D, et al. Treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide does not overcome poor outcome from metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in men with the germline homozygous HSD3B1 c.1245C genotype. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(9):1178–1185.

- Fallara G, Lissbrant IF, Styrke J, et al. Observational study on time on treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide. PLOS One. 2020;15(12):e0244462.

- Hemelrijck MV, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. Cohort profile: the national prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):956–967.

- Lissbrant IF, Eriksson MH, Lambe M, et al. Set-up and preliminary results from the patient-overview prostate cancer. Longitudinal registration of treatment of advanced prostate cancer in the national prostate cancer register of Sweden. Scand J Urol. 2020;54(3):227–228.

- Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, et al. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2019;22(1):23–30.

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–656.

- Wettermark B, Hammar N, MichaelFored C, et al. The new Swedish prescribed drug register-opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726–735.

- Fallara G, Lissbrant IF, Styrke J, et al. Rapid ascertainment of uptake of a new indication for abiraterone by use of three nationwide health care registries in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(1):56–60.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Berglund A, Garmo H, Tishelman C, et al. Comorbidity, treatment and mortality: a population based cohort study of prostate cancer in PCBaSe Sweden. J Urology. 2011;185(3):833–840.

- Cazzaniga W, Ventimiglia E, Alfano M, et al. Mini review on the use of clinical cancer registers for prostate cancer: the national prostate cancer register (NPCR) of Sweden. Frontiers Medicine. 2019;6:51.

- Goodman OB, Flaig TW, Molina A, et al. Exploratory analysis of the visceral disease subgroup in a phase III study of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17(1):34–39.

- Loriot Y, Eymard J-C, Patrikidou A, et al. Prior long response to androgen deprivation predicts response to next-generation androgen receptor axis targeted drugs in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(14):1946–1952.