Abstract

Aim

To compare prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with cancer and general population controls.

Method

In two stratified nationally representative surveys, the 12-month prevalence of mental disorders was assessed in 2141 patients with cancer and 4883 general population controls by the standardized Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). We determined odds ratios (ORs) to compare the odds for mental disorders (combined and subtypes) in cancer patients with age- and gender-matched controls.

Results

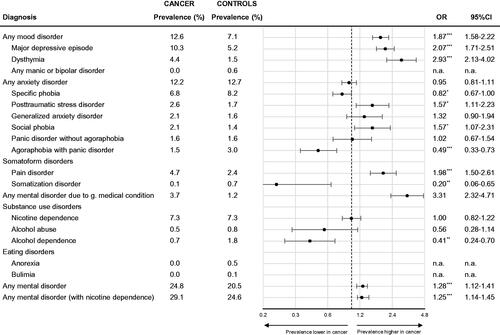

The 12-month prevalences rate for any mental disorder was significantly higher in patients with cancer compared to controls (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.14–1.45). Prevalence rates were at least two times higher for unipolar mood disorders (major depression: OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.71–2.51; dysthymia: OR 2.93, 95% CI 2.13–4.02) and mental disorders due to a general medical condition (OR 3.31, 95% CI 2.32–4.71). There was no significant elevation for anxiety disorders overall (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81–1.11). Mildly elevated prevalence rates emerged for post-traumatic stress disorder (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.11–2.23) and social phobia (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.07–2.31), while specific phobia (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.00) and agoraphobia (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.33–0.73) were significantly less frequent in cancer.

Conclusions

While elevated depression rates reinforce the need for its systematic diagnosis and treatment, lower prevalences were unexpected given previous evidence. Whether realistic illness-related fears and worries contribute to lower occurrence of anxiety disorders with excessive fears in cancer may be of interest to future research.

Introduction

High levels of subjective distress, psychiatric symptoms, and mental disorders are documented in patients with cancer [Citation1–3]. Living with a life-threatening disease may lead to an increased psychosocial burden as individuals confront a variety of stressors throughout the disease trajectory [Citation4]. Some tumors and treatments have been linked to neuropsychiatric mechanisms that underlie depression and anxiety [Citation5]. While many patients experience relevant yet non-pathological symptoms of distress, exposure to cancer-related stressors may substantially increase the risk for mental health problems [Citation6]. The diagnosis of a mental disorder is not only associated with a significantly reduced quality of life, but has also been linked to treatment non-adherence and critical health behavior in patients with cancer [Citation7].

The extent to which mental disorders are more prevalent in patients with cancer compared to controls is however difficult to evaluate from the current literature. Evidence from large health claims databases indicates a significantly increased clinical incidence of first-onset mental disorders after cancer [Citation8–11]. Depending on the time interval under study, the risk for any mental disorder compared to controls ranged from 6.7 in the first week after diagnosis to 1.7 in the first year after diagnosis.

While the aforementioned studies analyzed clinical diagnoses made on occasion of treatment in medical and mental health care facilities, survey studies have used structured diagnostic interview schedules to determine the presence of mental disorders in patients with cancer vs. controls. A large international study showed a significant 1.4-fold increase in 12-month prevalence rates of any mood or anxiety disorder in 357 patients with cancer compared to 64,657 cancer-free individuals [Citation12]. In another large recent survey, Mallet et al. [Citation13] compared 12-month prevalence rates of subtypes of mental disorders in 1300 patients with cancer and 35,009 general population controls. In this study, the prevalence rates did not differ significantly for all mental disorders combined, while odds ratios (ORs) ranged remarkably in size and direction across mental disorder types.

The current evidence regarding the risk for mental disorders in patients with cancer vs. controls relies predominantly on registered routine clinical diagnoses although standardized diagnostic interview assessments are more reliable [Citation14]. Moreover, the potential variation of risks in cancer vs. controls or aggregate prevalence rates is underinvestigated. The risk might be higher for affective and lower for anxiety and substance-related mental disorders [Citation9,Citation13]. While it has been established that, within cancer populations, younger and female individuals are more distressed [Citation15], it is not clear whether this pattern exceeds the same effect in the general population were mental disorders are also more frequent in those groups. The results for early vs. advanced disease and tumor sites are mixed. This study aimed to

a) compare the prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with cancer and age- and gender-matched controls and

b) explore prevalence rates in disease-related and sociodemographic subgroups of cancer patients compared to age- and gender-matched controls.

The prevalence data for both samples have been published [Citation16–18], this study focuses on the systematic age and gender-matched comparison of prevalence rates in both samples.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We analyzed data from two nationwide epidemiological studies. Cancer patients were recruited in a multicenter cross-sectional study from the following treatment settings: oncological inpatient clinics at acute care hospitals, specialized outpatient cancer care facilities, and inpatient cancer rehabilitation centers across Germany between July 2008 and December 2010 [Citation16,Citation19]. Sampling was stratified according to the frequency of tumor entities in Germany to establish a representative sample of cancer patients. Exclusion criteria were the following: age younger than 18 or older than 75 years, severe cognitive or physical impairment, and language barrier. No exclusion criteria regarding time since diagnosis were applied. The research ethics committee of the local medical association in each study center approved this study.

After providing written informed consent, all participants were screened with the Patient-Health-Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Patients with sum scores ≥ 9 were further assessed by a standardized diagnostic interview for mental disorders. Patients with sum scores < 9 were randomly assigned to the interview. Out of 5889 eligible cancer patients, 4020 (68%) participated in the study. See Mehnert et al. [Citation16] for a flowchart illustrating participation across screening arms. In total, 2141 patients completed the CIDI-O and were analyzed in this study. We adjusted for the oversampling of patients screened ≥ 9 on the PHQ-9 by applying the according design weights in all analyses.

General population controls were analyzed from the mental health submodule of the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1-MH). The DEGS1 recruited individuals aged 18–79 years from local population registries between November 2008 and December 2011 using a two-stage stratified random sampling procedure. Sampling was stratified for age, gender, and geographical location. Detailed information about the DEGS1 and DEGS1-MH design, sampling strategy, and representativity is available from Scheidt-Nave et al. [Citation20] and Jacobi et al. [Citation21]. The DEGS1-MH received ethical approval from the research ethics board of the Technical University Dresden. Out of 6,028 DEGS1 participants eligible for DEGS1-MH, 4483 completed the full DEGS1-MH survey including the CIDI. Design weights were applied to account for different probabilities of participation in different strata.

We determined a physically healthy subgroup of the general population sample by excluding all DEGS1-MH participants with the following diagnosed chronic health conditions present in the last 12 months: chronic musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurologic, allergic, thyroid, or lower respiratory tract diseases, cardiometabolic conditions, and cancer. The presence of these chronic health conditions was assessed as part of the DEGS1 procedures by a standardized physician-administered computer-based health interview and examination, standardized measurements, and laboratory tests [Citation20]. N = 990 (22%) individuals in the general population sample were physically healthy and had none of the assessed chronic health conditions.

Measures

The 12-month prevalence of mental disorders was assessed by the standardized computer-assisted Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The diagnostic assessment was done upon recruitment and thus included patients at various time intervals since first cancer diagnosis. The following mental disorders were covered in the cancer as well as the general population sample: disorders due to general medical condition (F06.x); mood disorders: mania and bipolar I disorder (F30.1, F31.1), hypomania and bipolar II disorder (F30.0, F31.0), major depressive episode (F32.1/.2), dysthymia (F34.1); anxiety disorders: agoraphobia with panic disorder (F40.01), panic disorder without agoraphobia (F41.0), generalized anxiety disorder (F41.1), social phobia (F40.1), any specific phobia (F40.2), posttraumatic stress disorder (F43.1); somatoform disorders: pain disorder (F45.4), somatization disorder (F45.1); anorexia (F50.0), bulimia (F50.2), alcohol abuse (F10.1), alcohol dependence (F10.2), and nicotine dependence (F17.2).

Statistical analysis

We firstly merged the prevalence data from both samples into one dataset. We then calculated a single design weight by combining both samples’ design weights, scaled to a mean value of 1. We used propensity scores to adjust the age and gender distribution in the general population sample to match the age and gender distribution in the cancer sample [Citation22,Citation23]. To establish this matched distribution of age and gender in both subsamples, we calculated the propensity score (ρ, predicted probability) in the design-weighted data using the cancer sample as a reference population. The propensity score was calculated using a binary outcome logistic regression model that predicted the probability for each participant to be assigned to the cancer sample (1) vs. the general population sample (0) based on the predictors age, gender, and the interaction age × gender. The interaction term was employed to account for the high frequency of specific age and gender combinations in the cancer sample. The resulting propensity score was then applied to the combined unweighted data set by assigning each participant in the cancer sample a weight of 1 and each participant in the general population sample a weight of ρ/(1 − ρ) [Citation23]. We further rescaled the propensity score weight to have a mean value of 1.

We then calculated the prevalence rates for all assessed mental disorders in the propensity score weighted data set. ORs were calculated to determine the odds for mental disorders in cancer patients compared to age, gender, and age × gender-matched general population controls. We calculated an analogous analysis comparing cancer patients with the physically healthy subgroup of the general population sample. We further calculated prevalence rates for any mental disorder by demographic and disease-related subgroups of the cancer sample and compared them with according prevalence rates in matched controls. We used SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

shows demographic and disease-related characteristics of the cancer sample before weighting. The mean age of the general population sample was M = 51.4 (SD = 16.4), 52.2% were female. Sample characteristics after weighting are shown in Table S1.

Table 1. Demographic and disease-related characteristics of the cancer sample, unweighted (n = 2141).

shows that the 12-month prevalences rate for any mental disorder was significantly higher in patients with cancer compared to age and gender-matched controls (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.14–1.45). Patients with cancer showed moderately elevated prevalence rates for mental disorders due to a general medical condition (OR 3.31, 95% CI 2.32–4.71) and unipolar mood disorders including dysthymia (OR 2.93, 95% CI 2.13–4.02) and major depression (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.71–2.51), as well as pain disorder (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.50–2.61).

Figure 1. Comparison of mental disorder prevalence rates in patients with cancer (n = 2141) vs. age and gender-matched general population controls (n = 4483). Prevalence rates in controls were weighted based on propensity score-matching. Matching accounted for age, gender, and age × gender interaction. 12-month-prevalence rates were assessed. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001.

Comparison of prevalence rates for anxiety disorders yielded a complex pattern. For all anxiety disorders combined, there was no significant difference between patients with cancer and matched controls (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81–1.11). For subtypes of anxiety disorders, prevalence rates showed significant, but small deviations between the cancer and general population samples. While post-traumatic stress disorder (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.11–2.23) and social phobia (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.07–2.31) were significantly more frequent in cancer patients, specific phobia (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.00), and agoraphobia (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.33–0.73) were significantly less frequent in cancer. Alcohol dependence was also significantly less frequent in cancer (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.24–0.70).

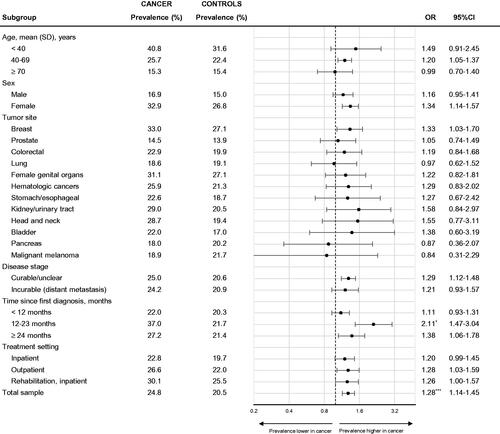

compares prevalence rates for any mental disorder in subgroups of cancer patients and age and gender-matched controls. Although younger, female and patients with head and neck, kidney/urinary tract, and breast cancer showed elevated prevalence rates compared to controls (ORs 1.33–1.57), most of the respective ORs were not significant due to small sample sizes in subgroup analyses. There was also no difference between early stage and metastasized cancer: the prevalence rates were similarly increased compared to controls in both groups. Although the pattern was largely similar for mood disorders (Supplement Figure S1), patients with lung and pancreatic cancer showed a non-significant increase of prevalence rates compared to controls when only mood disorders were considered, and decrease when only anxiety disorders were considered (Supplement Figure S2).

Figure 2. Prevalence rates for any mental disorder (without nicotine dependence) in patients with cancer vs. age and gender-matched controls by demographic and disease-related subgroups. Each medical subgroup (e.g., breast cancer) is compared with accordingly matched non-cancer controls, i.e., breast cancer patients (left column) are compared with female controls of matching age (right column). Prevalence rates in controls were weighted based on propensity score-matching. Matching accounted for age, gender, and age × gender interaction. 12-month-prevalence rates were assessed. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001.

Results were largely similar when prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with cancer were compared to physically healthy (no diagnosis of a chronic medical condition) individuals from the general population (Supplement Figure S3). There was a larger difference for mental disorders due to a general medical condition compared to the healthy subsample (cancer vs. general OR 3.31, cancer vs. healthy OR 6.37) and nicotine dependence (cancer vs. general OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.82–1.22, cancer vs. healthy OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47–0.79).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study so far comparing prevalence rates for mental disorder subtypes in patients with cancer vs. matched controls using standardized diagnostic interview assessments in nationally representative samples. Our result of a 1.3-fold increased prevalence rate in patients with cancer is in line with previous studies showing a 1.4–2.2-fold higher risk for a mental disorder when mood, anxiety, and stress reaction disorders were studied combined [Citation11,Citation12,Citation24].

Depending on the type and subtype of mental disorder, we found higher or lower prevalence rates among patients with cancer compared to controls. A compared to the present two to three times higher rate for unipolar depression, similarly increased risk one year after diagnosis has been found in some earlier studies [Citation8,Citation9,Citation11,Citation24], while others reported a smaller ratio of 1.7 [Citation10,Citation12]. The significantly lower prevalence rates in this study for some anxiety disorders (agoraphobia and simple phobia) were unexpected given previous studies [Citation9] showing 1.5–2 times higher rates of anxiety disorders in cancer [Citation9,Citation12,Citation24]. One exception is the study of Mallet et al. [Citation13] showing no significant difference for all anxiety disorders. As discussed further below, the dominance of realistic illness-related fears over excessive fear or worry in the context of a life-threatening disease might have contributed to partially lower prevalence rates of anxiety disorders, although we do not have sufficient data in this study to substantiate this assumption. The present mildly increased rate of PTSD is in line with a recent systematic review [Citation25].

We found lower rates of substance use disorders in cancer patients compared to controls, similar to earlier studies [Citation13,Citation26]. As Mehnert et al. [Citation16] discussed, this may be due to the small percentage of patients with alcohol- and tobacco-associated tumors according to the stratified cancer sample, interview reporting bias, or substance cessation after cancer. We found a three times higher rate of mental disorders due to a general medical condition. To our knowledge, there is no earlier study comparing this type of disorder in cancer vs. controls so far. The risk increase may reflect discussed pathophysiological effects of cancer and its treatment [Citation5]. Notably pain disorder, defined by persistent severe pain not sufficiently explainable by the cancer or another underlying medical condition, was also two times more frequent in cancer patients. Complex chronic pain is frequent in cancer survivors, and might be associated with a higher risk for pain disorder when untreated [Citation27].

Subgroups were too small to substantiate tendencies of greater vs. lower prevalence rate increases compared to controls in different age groups and cancer types. The overall pattern was largely similar to earlier studies with greater prevalence rate increases compared to controls among female and younger patients and lower or no prevalence rate increases in male or older patients [Citation8–10]. Cancer may exacerbate known vulnerability factors in these groups [Citation4]. Receiving a cancer diagnosis at a young age may also be associated with more substantial life disruption; female patients may report distress more openly [Citation1]. The pattern in patients with incurable, and relatedly lung and pancreatic cancer, is yet worthwhile of future investigation. It might tend toward lower prevalence of anxiety disorders compared to the general population. It might be hypothesized that anxiety disorders, defined by inadequate fears, are less frequent among individuals who are confronted with realistic death-related fears [Citation28].

The elevated 12-month prevalence rate for unipolar depression strengthens the need for systematic diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of depression in patients with cancer as shown effective through for example integrated collaborative care programs [Citation29]. In a substantial proportion of cancer patients with a diagnosed mental disorder, a history of this disorder before the diagnosis of cancer has been reported, ranging from 40% for major depression to 77% for PTSD and 90% for specific phobia [Citation13]. Taking elevated depression rates in patients with cancer together with its heterogeneous clinical presentation, adequate treatment reflecting individual patients’ supportive and mental health care needs remains challenging [Citation30]. As systematic evidence for specialized treatments for cancer-related depression is limited [Citation31,Citation32], further investigation of potential depression subgroups with varying cancer-related or other psychopathological mechanisms may contribute intervention development.

As a limitation to our study, bias may have occurred by analyzing data from two separate studies. However, the analogous computer-assisted assessment procedure supports comparability of the data. Our results do further not reflect recent changes to the DSM. Adjustment disorders were not included in the study because they were not assessed in the general population sample. Comparing the 12-month prevalence rates of adjustment disorder in the present cancer sample of 11.1% [Citation18] with that of 2.3% in a Swiss study in older adults [Citation33], an increase compared to controls is likely. The samples’ heterogeneity regarding time since diagnosis, disease phase, and tumor stage limits conclusions about mental disorder occurrence in response to potentially challenging events over the cancer trajectory including diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and recurrence. We did also not study the impact of hormonal treatments on mental health. Yet, the stratified cross-sectional design provides a representative overall estimate of mental disorder prevalence rates in cancer. Comparing the 4-week-prevalence rates of mental disorders in cancer vs. controls would have provided a more precise picture but was not possible due to lack of according data in the general population sample.

Conclusion

Results strengthen the need for systematic diagnosis and treatment of depression in cancer. Generalized conclusions about the extent of mental health burden across other types of mental disorders remain difficult. Further research is needed to enlighten the yet inconclusive pattern for anxiety disorders and substance use disorders. The contribution of realistic illness-related fears and worries to lower occurrence of anxiety disorders with excessive fears in cancer may be of interest in this regard.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SV, AM, UK; Data curation: SV, AM, KK, RK; Formal analysis: SV, RP; Funding acquisition: AM, UK; Methodology: AM, KK, RK, UK; Project administration: AM, UK; Resources: MH, KK, RK; Writing – original draft: all authors, Writing – review & editing: all authors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (848.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and effort.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carlson LE, Zelinski EL, Toivonen KI, et al. Prevalence of psychosocial distress in cancer patients across 55 North American cancer centers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(1):5–21.

- Zhu J, Fang F, Sjölander A, et al. First-onset mental disorders after cancer diagnosis and cancer-specific mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1964–1969.

- Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):343–350.

- Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415.

- Smith HR. Depression in cancer patients: pathogenesis, implications and treatment. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(4):1509–1514.

- Dekker J, Braamse A, Schuurhuizen C, et al. Distress in patients with cancer - on the need to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(7):1026–1029.

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB. Impact of depression on treatment adherence and survival from cancer. In: Kissane DW, Maj M, Sartorius N, editors. Depression and cancer. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. p. 101–124.

- Akechi T, Mishiro I, Fujimoto S, et al. Risk of major depressive disorder in Japanese cancer patients: a matched cohort study using employer-based health insurance claims data. Psycho-Oncology. 2020;29(10):1686–1694.

- Lu D, Andersson TML, Fall K, et al. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders immediately before and after cancer diagnosis: a nationwide matched cohort study in Sweden. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1188–1196.

- Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, et al. Increased risk for depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in Denmark, 1998–2011. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–3839.

- Hung YP, Liu CJ, Tsai CF, et al. Incidence and risk of mood disorders in patients with breast cancers in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2227–2234.

- Nakash O, Levav I, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Comorbidity of common mental disorders with cancer and their treatment gap: findings from the world mental health surveys. Psychooncology. 2014;23(1):40–51.

- Mallet J, Huillard O, Goldwasser F, et al. Mental disorders associated with recent cancer diagnosis: results from a nationally representative survey. Eur J Cancer. 2018;105:10–18.

- Rogers R, Williams MM, Wupperman P. Diagnostic interviews for assessment of mental disorders in clinical practice. In: Llewellyn C, editor. Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine. 3rd ed. Cambridge; New York (NY): Cambridge University Press; 2019. p. 179–183.

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):343–351.

- Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3540–3546.

- Jacobi F, Höfler M, Siegert J, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the mental health module of the German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(3):304–319.

- Kuhnt S, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(5):289–296.

- Mehnert A, Koch U, Schulz H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychosocial distress and need for psychosocial support in cancer patients – study protocol of an epidemiological multi-center study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:70.

- Scheidt-Nave C, Kamtsiuris P, Gößwald A, et al. German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS) - design, objectives and implementation of the first data collection wave. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:730.

- Jacobi F, Mack S, Gerschler A, et al. The design and methods of the mental health module in the german health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22(2):83–99.

- Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661–3679.

- Morgan SL, Todd JJ. 6. A diagnostic routine for the detection of consequential heterogeneity of causal effects. Sociol Methodol. 2008;38(1):231–282.

- Härter M, Baumeister H, Reuter K, et al. Increased 12-month prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):354–360.

- Swartzman S, Booth JN, Munro A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after cancer diagnosis in adults: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(4):327–339.

- Milam J, Slaughter R, Meeske K, et al. Substance use among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(11):1357–1362.

- Glare PA, Davies PS, Finlay E, et al. Pain in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1739–1747.

- Curran L, Sharpe L, Butow PN. Anxiety in the context of cancer: a systematic review and development of an integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;56:40–54.

- Sharpe M, Walker J, Hansen CH, et al. Integrated collaborative care for comorbid major depression in patients with cancer (SMaRT oncology-2): a multicentre randomised controlled effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1099–1108.

- Pirl WF, Roth AJ. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in cancer patients. Oncology. 1999;13(1293):1305–1306.

- King A. Behind the bright headlines, mind the long shadows. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(5):588–592.

- Walker J, Sawhney A, Hansen CH, et al. Treatment of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2014;44(5):897–907.

- Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Enzler A, et al. Adjustment disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive disorders in old age: findings from a community survey. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):113–120.