Abstract

Background

Psychological distress may be present among patients who are considering enrollment in phase 1 cancer trials, as they have advanced cancer and no documented treatment options remain. However, the prevalence of psychological distress has not been previously investigated in larger cohorts. In complex phase 1 cancer trials, it is important to ensure adequate understanding of the study premises, such as the undocumented effects and the risk of adverse events.

Materials and methods

In a prospective study, patients completed questionnaires at two time points. We investigated psychological distress, measured as stress, anxiety, and depression, among patients at their first visit to the phase 1 unit (N = 229). Further, we investigated the understanding of trial information among patients who were enrolled in a phase 1 cancer trial (N = 57).

Results

We enrolled 75% of 307 eligible patients. We found a lower mean score of stress in our population compared to population norms, while the mean scores of anxiety and depression were higher. A total of 9% showed moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and 11% showed moderate to severe symptoms of depression, which indicates higher levels than cancer patients in general. A total of 46 (81% of enrolled patients) completed questionnaires on trial information and consent. The understanding of the information on phase 1 cancer trials in these patients was slightly lower than the level reported for cancer trials in general. Some aspects relating to purpose, benefit, and additional risks were understood by fewer than half of the patients.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that distress is not as prevalent in the population of patients referred to phase 1 cancer trials as in the general cancer population. Although patients’ understanding of trial information was reasonable, some aspects of complex phase 1 cancer trials were not easily understood by enrolled patients.

Background

Participation in a phase 1 cancer trial is an option for patients with metastatic, progressive cancer disease who have exhausted all standard treatments but have good performance status. However, in the absence of clinical response, patients are at risk of rapid deterioration, which may cause psychological distress. The prevalence of psychological distress is not well documented in phase 1 settings. A meta-analysis of 4,000 cancer patients with advanced or late-stage cancer found that the prevalence of anxiety was 10%, and depression was 17% based on diagnostic psychiatric interviews [Citation1]. The prevalence of depression may be higher in a phase 1 setting, as suggested by three cross-sectional and two prospective studies including between 31 and 46 patients of which 3–49% demonstrated depression based on screening questionnaires [Citation2–6]. The prevalence of anxiety may also be higher as shown by a cross-sectional study that found a high anxiety score among 20% of 31 patients in phase 1 cancer trials [Citation2]. The occurrence of stress has not been reported among patients in phase 1 cancer trials, although its negative impact on cancer patients’ quality of life has been documented [Citation7].

The primary purpose of a phase 1 cancer trial is to determine a recommended dose and define a safety profile [Citation8]. The effects of the investigational treatment are undocumented. It is important to ensure that patients understand the trial premises before enrollment. However, in a systematic review including 30 studies of 2,788 patients, we demonstrated a consistent pattern of limited understanding [Citation9]. The development of personalized treatment strategies based on genomic profiling adds further complexity, which may complicate the identification of phase 1 cancer trials as experimental by potential participants.

To address the limitations of existing research, we prospectively investigated the levels of psychological distress measured as stress, anxiety, and depression among cancer patients referred to a phase 1 unit. Further, we investigated patients’ understanding of the information provided before consenting to participate in such trials.

Materials and methods

The reporting of this study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [Citation10].

Study design

This study was conducted from 10 March 2017, to 2 April 2018. Patients completed a questionnaire at their first visit to the phase 1 unit and a second questionnaire if invited to enroll in a phase 1 cancer trial. It was highlighted that participation in the study had no impact on their management in the unit.

Setting

The study was carried out in the phase 1 unit of the Department of Oncology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet. It is the only dedicated phase 1 unit in Denmark and receives patient referrals from the entire nation. Patients are referred by their oncologist when their treatment options have been exhausted, or when conventional therapy has limited expected benefit. The selection of patients for phase 1 cancer trials is based in part on the next-generation sequencing taking place at the unit. On their first visit, patients receive general information on phase 1 cancer trials and receive specific trial information at enrollment.

Participants

Patients were invited to participate in the study at their first visit to the phase 1 unit. Patients were excluded if they did not read or write Danish, or if they were not eligible (mainly due to poor performance status).

Data sources/measurements

Data sources were paper-form questionnaires administered during visits to the phase 1 unit, which were completed either in the department or at home and returned at the next visit or by mail.

Psychological distress was measured at the first visit. At enrollment, patients gave informed consent to a trial, and their understanding of the trial information was assessed.

We used official Danish translations of the validated scales given below except Quality of Informed Consent, which was translated into Danish following the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer translation manual [Citation11] and linguistically validated among nine patients enrolled in a phase 1 cancer trial.

Measurements in the questionnaire completed at the first visit to the phase 1 unit

Demographics

Self-reported demographics were registered at referral as gender (male/female), age (continuous), cohabitation (with/without a partner), children (yes/no), and education (highest attained level in three categories: elementary and junior high school, high school or vocational education, or higher education >12 years.)

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) assesses the extent to which respondents consider their situation as stressful [Citation12]. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale as the total sum (0–40) [Citation12,Citation13]. No clinically relevant cutoff was defined. In the original 14-item version, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.75 [Citation13]. Validation of the Danish version of the 10-item version showed good scale reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 [Citation14].

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) is a validated 7-item scale that identifies cases with generalized anxiety based on symptom severity in the past two weeks, resulting in a total score of 0 to 21 reflecting increasing severity [Citation15]. Cutoffs for severity were 0–4 (minimal), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), and 15–21 (severe). The scale reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 [Citation15].

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a validated 9-item scale that evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms in the past two weeks, resulting in a total score of 0 to 27 [Citation16]. Cutoffs for categories of increasing severity of depressive symptoms were 0–4 (minimal), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), and 20–27 (severe). The scale reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 [Citation17].

Measurements in the questionnaire completed at enrollment in a trial

Quality of Informed Consent (QuIC), part A, was developed by American researchers to assess the informed consent process by measuring patients’ objective understanding of cancer clinical trials (phases 1, 2, and 3). Based on federal regulations governing research with human subjects, the scale covers eight domains concerning different aspects of informed consent, such as purpose, risks, benefits, and voluntary nature. A total of 20 statements result in a total mean score between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating better understanding. The validation is limited, but good test-retest reliability and content validity have been reported [Citation18]. We included 17 statements relevant to phase 1 cancer trials and a Danish setting.

Statistical methods

The levels of perceived stress, anxiety, and depression were compared with population norms using the Welch modified two-sample t-test. Normative data from the general population served as the reference data for our findings. Normative data for PSS were provided from a random sample in Sweden drawn from the municipal register of 3,406 individuals (response rate 40% of all invited) aged 18–79 in 2010 [Citation19]. In this sample, the mean age was lower than that of our population (left-skewed age distribution). Norm scores among the elderly only (defined as age 55–79) were also reported, and since this age group was more comparable to our population, we compared our data with this group as well as with the whole sample.

Normative data for GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were obtained from a representative sample of the German population aged 14 years or older based on addresses of 5,036 individuals (response rate 73%) in 2006 for GAD-7 [Citation20] and 5,018 individuals (response rate 63%) in two waves in 2003 and 2008 for PHQ-9 [Citation11], respectively.

The results of the questionnaire measuring understanding of trial information were presented descriptively. Data were presented using the software R version 3.6.1.

Ethics

All participants in the study received oral and written information following Danish legislation and the Helsinki Declaration [Citation21] and completed a consent form. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (file number RH-2016-283). Ethical approval from the National Committee on Health Research Ethics was not required.

Results

Participants

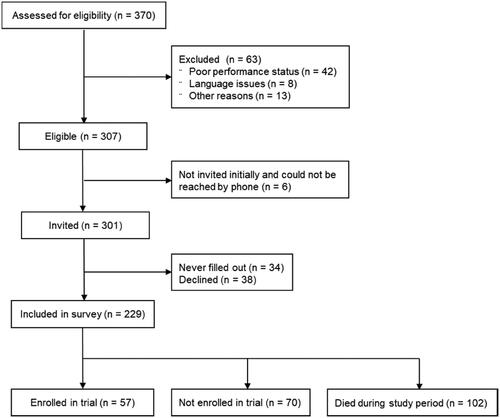

Among 307 patients who met the eligibility criteria for the study, 229 (75%) were enrolled. A total of 57 patients were enrolled in a phase 1 cancer trial and 102 patients died within the study period (). The median time from referral to the end-of-study was 227 days (range 7–388 days). For patients enrolled in a trial, the median time from referral to enrollment was 39 days (range 0–297 days). Of these patients, 46 (81%) completed a questionnaire at enrollment.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the inclusion of patients in the present study. Among referred patients, 83% were eligible; a total of 75% filled in the questionnaire at referral. Note: Other reasons for exclusion were referral for genomic profiling for causes other than possible enrollment in a phase 1 cancer trial.

The median patient age was 63 years. The largest diagnostic group of patients was diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer. The majority of patients had previously received two to four lines of treatment and had very limited comorbidity ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics based on self-reported information and patient chart reviews for referred patients (N = 229).

Psychological distress

The levels of stress, anxiety, and depression at the first visit are shown in .

Table 2. Distribution of the severity of stress, anxiety, and depression among patients at first visit (N = 229).

Psychological distress compared to population norms

The mean stress score in our population was 12.7 (standard deviation (SD) 6.0) vs. 14.0 (SD 6.3) in norm scores [Citation19], which was statistically significantly lower (p = 0.002). Norm scores among the elderly only (defined as age 55–79) were lower with a mean score of 12.9 (SD 6.0). There was no statistical difference in mean scores among the elderly and our study population.

The mean anxiety score in our population was 4.0 (SD 3.8) vs. 3.0 (SD 3.4) in norm scores [Citation20], and the mean depression score in our population was 5.0 (SD 4.0) vs. 2.9 (SD 3.5] in norm data [Citation11], which were both statistically significantly higher (p = 0.0002 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

At the first visit, 9% of the patients in our study had moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and 11% had moderate to severe symptoms of depression. In population norms, the prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety was 6% [Citation20], and the prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms of depression was 6.7% [Citation11].

Understanding of trial information

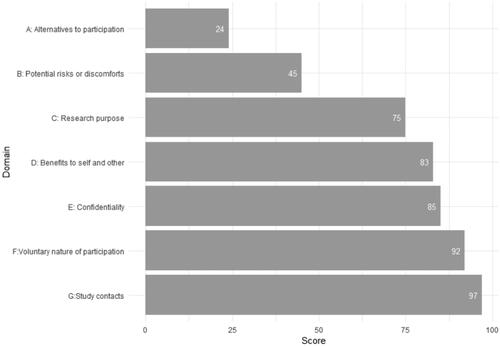

The mean QuIC was 73.6 (range 44–96, SD 9.7). The mean scores within the domains are shown in . Domains covering statements on potential risks and alternatives to participation had the lowest mean scores.

Figure 2. Mean scores of objective understanding of trial information measured with the Quality of Informed Consent Questionnaire, presented for each domain, among enrolled patients (N = 46).

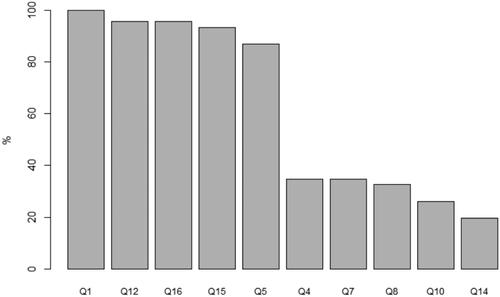

presents the five statements with the highest proportion of correct answers and the five with the lowest proportion. Fewer than 50% of patients correctly answered statements on the trial’s purpose (identification of trial as research; recognition of dose escalation regimen), benefit (unproven nature), additional risks compared to standard treatment, and disclosure of alternatives.

Figure 3. Proportion of patients (N = 46) responding correctly to each statement in the Quality of Informed Consent Questionnaire. Best: Q1. When I signed the consent form for my current cancer therapy, I knew that I was agreeing to participate in a clinical trial (correct answer: agree). Q12. By participating in this clinical trial, I am helping the researchers learn information that may benefit future cancer patients (correct answer: agree). Q16. If I had not wanted to participate in this clinical trial, I could have declined to sign the consent form (correct answer: agree). Q15. The consent form I signed lists the name of the person (or persons) whom I should contact if I have any questions or concerns about the clinical trial (correct answer: agree). Q5. In my clinical trial, one of the researchers’ major purposes is to test the safety of a new drug or treatment (correct answer: agree). Worse: Q4. All the treatments and procedures in my clinical trial are standard for people with my type of cancer (correct answer: disagree). Q7. The treatment being researched in my clinical trial has been proven to be the best treatment for my type of cancer (correct answer: disagree). Q8. In my clinical trial, each group of patients receives a higher dose of the treatment than the group before, until some patients have serious side effects (correct answer: agree). Q10. Compared with standard treatments for my type of cancer, my clinical trial does not carry any additional risks or discomforts (correct answer: disagree). Q14. My doctors did not offer me any alternatives besides treatment in this clinical trial (correct answer: disagree). Q: question.

Discussion

Based on the screening questionnaires, the level of psychological distress among patients referred to a phase 1 cancer trial unit was low. Patients understood most of the information on phase 1 cancer trials, although some critical aspects were poorly understood.

The main strength of our study was the relatively large cohort of prospectively collected data from more than 200 patients and the use of validated questionnaires whenever available. Furthermore, whereas patients’ understanding of trial information has previously been evaluated using a variety of study-specific questionnaires [Citation9], we applied a semi-validated questionnaire that allowed us to compare our results with those of other studies. The translation procedures followed international guidelines. Further, we consider our enrollment percentage of 75% of the eligible patients a strength; this was a population with end-stage cancer who may have been overwhelmed by participating in this study. Thus, the risk of inclusion bias was limited. Limitations included the risk of response bias; although patients were informed that their chance of enrolling in a phase 1 cancer trial was independent of their participation in the study and the study results, some may have answered more positively regarding psychological distress, thus affecting the study’s validity. Alternatively, being asked about study-specific aspects may have led to the improvement of patients’ attention to consigned trial information, thereby leading to a better mean score in QuIC. Furthermore, the comparison with population norms for anxiety and depression was limited by the difference in age distribution in our study population than for reported normative data. For both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, there was a statistically significant difference in score according to age group, with a tendency toward higher scores among older people [Citation11,Citation20], thus reducing the difference in mean score compared to our population. For all three studies reporting normative data, the distribution between genders was equal, as in our study population. However, our population had a higher proportion of more educated people when compared to those in the three studies. Normative data on PSS, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 were not reported according to the level of education [Citation11,Citation19,Citation20]. The selection of patients with a higher socioeconomic position in phase 1 trials was presented in a Danish registrar study [Citation22].

We found a lower mean level of stress in our population of patients referred to a phase 1 unit compared to population norms [Citation19], although there was no difference when considering age distribution. Stress levels have not been widely measured among cancer patients; however, we found it relevant to measure distress in our population. To our knowledge, PSS is the only validated scale that evaluates the extent to which individuals perceive their situation as stressful. Among 2252 testicular cancer survivors, the median PSS score was 11 (IQR 7–16) [Citation23], which is lower than that of our population (13) (IQR 9–16). A study of 111 women undergoing breast cancer surgery found a mean level of stress of 17.6 (SD 6.7) [Citation24], which was higher than the 12.7 (SD 6.0) in our population. These comparisons are difficult to make due to the very different populations, stages of cancer, and timing of measurements. In our population, it is reasonable to expect the level of stress to be higher. However, as presented in , 87% of the patients referred to the phase 1 unit had already received two or more previous treatments, which could be interpreted as being somewhat experienced in navigating future uncertainty.

The higher level of depression in our population compared to population norms was not surprising, as the association between cancer and subsequent depression is well known from registry data of more than 600,000 adults diagnosed with cancer [Citation25]. In our population, 11% had moderate-severe symptoms of depression (a score of ≥10 on the PHQ-9) [Citation17]. A control population of patients not referred to the Phase 1 Unit is not available, and although the clinical stage of the cancer and the limited treatment options are arguments for comparing patients in phase 1 cancer trials to patients in palliative-care settings, patients in phase 1 cancer trials have a better performance status. Nevertheless, we found a lower prevalence of depression than that of the 16–17% reported for both patients with mixed stages/early stages of cancer and late-stage cancer [Citation1]. Nine percent of the patients in our population had moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety (a score of ≥10 on the GAD-7), which is slightly lower than the prevalence of 10% among patients with both early and late-stage cancer [Citation1]. This suggests better psychological health in our population than in the general cancer population. Possible explanations include the referral of patients with better psychological health to the phase 1 unit, a selection bias in our population, or a psychological benefit gained from the prospect of a positive outcome through participating in a phase 1 cancer trial.

The QuIC has not been previously applied exclusively to patients consenting to phase 1 cancer trials. Cross-sectional studies including between 50 and 207 patients in phase 1, 2, and 3 trials reported mean QuIC scores of 77.8 (SD 9.4) [Citation26], 77.6 (95% CI, 75.7–79.4]) [Citation27], and 76.0 (SD 8.8) [Citation28], respectively, which was slightly higher than the score of 73.6 (SD 9.7) in our population; however, a score for patients specifically enrolled in phase 1 cancer trials was not reported in these studies. The reporting of scores within domains on different aspects of informed consent, as presented in a cross-sectional study of 282 patients in phase 2 and 3 cancer trials [Citation29], may explain this difference in the overall mean score. The domain scores in this study compared to our study reveal no pronounced differences except for the domain covering the specific statement ‘My doctors did not offer me any alternatives besides treatment in this clinical trial’. In our study, only 20% answered ‘disagree’ to the statement () compared to 75% of the population of patients in phase 2 and 3 cancer trials [Citation29]. There are several possible explanations for this. As the key eligibility criterion in phase 1 cancer trials is progression after standard-of-care treatments, some patients may have been told by their referring oncologist that there were no other treatment options. Further, palliative care as an alternative to a trial may not have been discussed with these patients due to their good performance status.

Other critical aspects of informed consent were poorly understood in this study. A total of 35% correctly responded ‘disagree’ to the statements ‘All the treatments and procedures in my clinical trial are standard for people with my type of cancer’ and to ‘The treatment being researched in my clinical trial has been proven to be the best treatment for my type of cancer’ (). Likewise, 26% answered ‘disagree’ to the statement ‘Compared with standard treatments for my type of cancer, my clinical trial does not carry any additional risks or discomforts’. These findings suggest that some patients may not recognize phase 1 cancer trials as research. This may be explained by the position of phase trials as a valid therapeutic option [Citation30]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement on phase 1 cancer trials acknowledges the importance of these trials in cancer treatment and emphasizes their therapeutic intent [Citation31,Citation32]. Indeed, advances in the understanding of genetic mechanisms underlying tumor biology have allowed for potential new targeted therapies that match tumors expressing a specific genomic alteration. Using this strategy, a median response rate (RR) of 31% was presented based on a meta-analysis of 346 studies [Citation33]. The evaluation of our phase 1 unit showed that among 500 patients biopsied for genomic profiling, 20% received a matched therapy, and 15% of these 101 patients had a partial response [Citation34]. One of the latest reviews of 224 studies suggested an overall RR of 20% in phase 1 cancer trials across both matched and non-matched trials [Citation35]. These promising results support the idea of therapeutic intent, although the research procedure may be less clear to patients.

Further, 33% answered ‘agree’ to the statement ‘In my clinical trial, each group of patients receives a higher dose of the treatment than the group before, until some patients have serious side effects’ (). However, this does not merely reflect misconceptions. Although phase 1 cancer trials are primarily designed as dose-escalation studies, some patients in our study were enrolled in the expansion part of the trials with a fixed dose of the investigational drug.

The QuIC enabled us to present the gaps in patients’ understanding of trial information. Whether these gaps represent insufficient information by physicians, the denial of the truth in patients or differences in the perspective of a changing research field cannot be exhaustively disclosed. However, knowledge of these gaps can guide healthcare professionals in information procedures.

Generalizability

There is a risk that patients experiencing higher levels of distress did not participate in our study, which may lead to the underestimation of the levels of psychological symptoms. As the participation percentage was high, the risk of inclusion bias was limited, and we expect our data to be representative of phase 1 units in general.

Conclusion

It is reassuring that psychological distress does not seem to be frequent in the population of patients referred to the phase 1 unit. Health care professionals working with this population should pay attention to their communication of all aspects of information, forming the fundament for consent to phase 1 cancer trials.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Examples of questionnaires, statistical codes, and deidentified participant data are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174.

- Tomamichel M, Jaime H, Degrate A, et al. Proposing phase I studies: patients’, relatives’, nurses’ and specialists’ perceptions. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(3):289–294.

- Cohen L, de Moor C, Amato RJ. The association between treatment-specific optimism and depressive symptomatology in patients enrolled in a phase I cancer clinical trial. Cancer. 2001;91(10):1949–1955.

- Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L, et al. Reasons given by patients for participating, or not, in phase 1 cancer trials. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(10):1490–1497.

- Rouanne M, Massard C, Hollebecque A, et al. Evaluation of sexuality, health-related quality-of-life and depression in advanced cancer patients: a prospective study in a phase i clinical trial unit of predominantly targeted anticancer drugs. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(2):431–438.

- Dunn LB, Wiley J, Garrett S, et al. Interest in initiating an early phase clinical trial: results of a longitudinal study of advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2017;26(10):1604–1610.

- Kreitler S, Peleg D, Ehrenfeld M. Stress, self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):329–341.

- Cook N, Hansen AR, Siu LL, et al. Early phase clinical trials to identify optimal dosing and safety. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(5):997–1007.

- Gad KT, Lassen U, Mau-Sørensen M, et al. Patient information in phase I trials: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):768–780.

- Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG, for the STROBE Initiative, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2007;4(10):e297–1654.

- Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):551–555.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Heal Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396.

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park (CA): Sage; 1988. p. 31–67.

- Eskildsen A, Dalgaard VL, Nielsen KJ, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the danish consensus version of the 10-item perceived stress scale. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41(5):486–490.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Jama. 1999;282(18):1737.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Joffe S, Cook E, Cleary P, et al. Quality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(2):139–147.

- Nordin M, Nordin S. Psychometric evaluation and normative data of the Swedish version of the 10-item perceived stress scale. Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(6):502–507.

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–274.

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194.

- Gad KT, Johansen C, Duun-Henriksen AK, et al. Socioeconomic differences in referral to phase I cancer clinical trials: a Danish matched cancer case-control study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(13):1111–1119.

- Kreiberg M, Bandak M, Lauritsen J, et al. Psychological stress in long-term testicular cancer survivors: a danish nationwide cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(1):72–79.

- Golden-Kreutz DM, Browne MW, Frierson GM, et al. Assessing stress in cancer patients: a second-order factor analysis model for the perceived stress scale. Assessment. 2004;11(3):216–223.

- Dalton SO, Laursen TM, Ross L, et al. Risk for hospitalization with depression after a cancer diagnosis: a nationwide, population-based study of cancer patients in Denmark from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1440–1445.

- Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, et al. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9295):1772–1777.

- Jefford M, Mileshkin L, Matthews J, et al. Satisfaction with the decision to participate in cancer clinical trials is high, but understanding is a problem. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:371–379.

- Schumacher A, Sikov WM, Quesenberry MI, et al. Informed consent in oncology clinical trials: a brown university oncology research group prospective cross-sectional pilot study. PLOS One. 2017;12(2):e0172957–13.

- Bergenmar M, Molin C, Wilking N, et al. Knowledge and understanding among cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(17):2627–2633.

- Adashek JJ, LoRusso PM, Hong DS, et al. Phase I trials as valid therapeutic options for patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(12):773–778.

- Weber JS, Levit LA, Adamson PC, et al. American society of clinical oncology policy statement update: the critical role of phase I trials in cancer research and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):278–284.

- Weber JS, Levit LA, Adamson PC, et al. Reaffirming and clarifying the American Society of Clinical Oncology's policy statement on the critical role of phase I trials in cancer research and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):139–140.

- Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, et al. Association of biomarker-based treatment strategies with response rates and progression-free survival in refractory malignant neoplasms. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1452–1458.

- Tuxen IV, Rohrberg KS, Oestrup O, et al. Copenhagen prospective personalized oncology (CoPPO)-clinical utility of using molecular profiling to select patients to phase I trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(4):1239–1247.

- Chakiba C, Grellety T, Bellera C, et al. Encouraging trends in modern phase 1 oncology trials. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2242–2243.