Abstract

Purpose

In a cross-sectional observational study to explore long-term satisfaction with treatment among men who had undergone radical prostatectomy (RP) or definitive pelvic radiotherapy (RT) for prostate cancer (PCa).

Methods

After mean 7 years from therapy (range: 6–8), 431 PCa-survivors (RP: n = 313, RT: n = 118) completed a mailed questionnaire assessing persistent treatment-related adverse effects (AEs) (Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite [EPIC-26]) and seven Quality indicators describing satisfaction with the health care service following a most often general practitioner (GP)-led follow-up plan. A logistic regression model evaluated the associations between long-term satisfaction and treatment modality, age, the seven satisfaction-related Quality indicators, and persistent AEs. The significance level was set at p< .05.

Results

Four of five (81%) PCa-survivors reported long-term satisfaction with their treatment. In a multivariable model, satisfaction was positively associated with sufficient information about treatment and AEs, patient-perceived sufficient cooperation between the hospital and the GP and sufficient follow-up of AEs (ref.: insufficient). Age ≥70 years (ref.: <70) and a rising summary score within the EPIC-26 sexual domain additionally increased long-term satisfaction. The treatment modality itself (RP versus RT) did not significantly impact on satisfaction.

Conclusions

The majority of curatively treated PCa-survivors are satisfied with their treatment more than 5 years after primary therapy. Sufficient information, improved cooperation between the hospital specialists and the responsible GP and optimized follow-up of AEs may further increase long-term satisfaction among prostatectomized and irradiated PCa-survivors.

Introduction

Radical prostatectomy (RP) and definitive pelvic radiotherapy (RT) represent curative treatment modalities for prostate cancer (PCa) with similar oncological outcomes, but the types and levels of treatment-related adverse effects (AEs) may vary [Citation1].

With an 8-year post-treatment overall survival rate of at least 75%, persisting AEs can affect the PCa-survivor’s life for many years [Citation2,Citation3]. Thus many PCa-survivors will repeatedly have contact with health care professionals not only for disease control, but also for handling of bothersome AEs.

Many authors have documented AEs following RP or RT [Citation4]. In the review of Ávila et al., post-RP incontinence and post-RT bowel problems are documented as the most frequent AEs followed by sexual dysfunction after both treatment modalities.

In Scandinavia, follow-up of PCa-survivors is recommended as shared care between the hospital specialists and the general practitioner (GP) [Citation5–7]. The GP is assumed to contact the specialist (urologist/oncologist) in case of suspicious signs of PCa-relapse or treatment-requiring AEs. However, only few studies have focused on satisfaction among PCa-survivors during long-term follow-up [Citation8–11]. These studies have emphasized the impact of AEs, patient participation, and information as key factors associated with satisfaction. No studies are available concerning the Norwegian PCa-survivors, and none of the mentioned studies have focused on the GP’s role, in spite of the increasing interest in a long-term GP-led follow-up plan in PCa-survivors.

With this background, this study deals with two questions: (1) What is the proportion of Norwegian men who more than 5 years after RP or RT are satisfied with their treatment in a GP-led follow-up strategy? (2) Which factors are associated with long-term satisfaction in these men?

Methods

Eligible patients were identified among PCa-survivors included in the Norwegian Urological Cancer Group (NUCG)-VII study, which from 2008 to 2010 included patients in whom RP or RT was planned. By three follow-up waves, this longitudinal questionnaire-based multicenter study aimed to document post-treatment AEs. At inclusion 914 men, planned for RP or RT, completed a pretreatment questionnaire. Of those, 902 finally underwent RP or RT. These men were again asked to complete a similar questionnaire 3 months, 1 year, and 3 years after their treatment. Selected findings related to the NUCG -VII study have been published elsewhere [Citation12,Citation13].

For the purpose of this study, patients who had responded to the 3-year questionnaire were in 2016 again asked to complete a long-term questionnaire. Finally, evaluable PCa-survivors fulfilled the two following criteria:

1)RP without post-RP radiotherapy or RT without salvage prostatectomy

AND

2)Completion of the long-term questionnaire with valid EPIC-26 domain summary scores.

The long-term questionnaire contained PCa-related questions (the Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite [EPIC-26]) [Citation14], sociodemographics and medical variables. Following published scoring instructions [Citation15], EPIC-26 single items and DSSs were converted to the range between 0 (worst) and 100 (best). Each domain summary score (DSS) thus consisted of four 25-point categories (0 to <25, 25 to <50, 50 to <75, and 75–100), indicating gradual decrease of the assessed AE [Citation9].

The long-term questionnaire also contained eight satisfaction-related questions, extracted from the Cancer Patient Experiences Questionnaire (CPEQ) [Citation16,Citation17]. This instrument assesses the patients’ perspective on their cancer care and has acceptable psychometric properties. For the purpose of this study, we verbally modified selected questions, addressing PCa patients. The PCa patients rated their experiences related to the specified questions by a score varying from 1 (worst) to 5 (best) (Supplementary Table 1). The outcome variable was the question: ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your prostate cancer treatment’? The responses to this question were dichotomized as ‘satisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’. Answers to the remaining seven satisfaction-related questions, Quality indicators, represented the independent variables, dichotomized as ‘sufficient’ or ‘insufficient’. Emerging mean values across PCa-survivors significantly differed between satisfied and dissatisfied men (Supplementary Table 2). After combining the seven Quality indicators in each patient, the resulting scale showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79).

The respondents also reported if a specialist or their GP had been mainly responsible for the PCa follow-up during the past 2 years. They also reported major comorbidity present by at least one of the following conditions: coronary artery disease, cardiac failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, stroke, and/or other cancer the past 5 years. Responses to how they evaluated their general health were dichotomized as ‘poor’ or ‘good/fair’, partner status as ‘single’ or ‘paired’ and level of education as ‘low’ (high school or less) or ‘high’ (university/college). The respondents also reported their most recent Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) level, and use of hormones.

The final research file also contained information provided by the Cancer Registry of Norway as type of treatment and tumor risk group in according to EAU guidelines [Citation1].

‘PCa relapse’ was defined as an elevated level of PSA (RP: ≥0.2 ng/ml, RAD: ≥2.0 ng/ml), current use of hormone therapy and/or irradiation to distant metastases.

Statistics

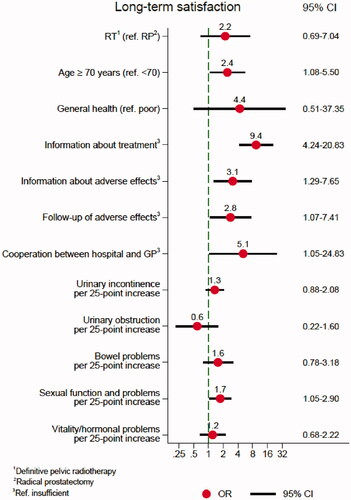

Standard descriptive statistics were presented by means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and by absolute numbers and proportions for categorical variables. The Independent t-tests and chi-square tests analyzed inter-group differences. Clinically relevant differences on continuous variables were described by Cohen’s d coefficient as small (0.2), medium (0.5) or large (0.8) [Citation18]. A multivariable logistic regression model assessed associations between long-term satisfaction and selected covariates: Treatment modality, age, AEs, and the Quality indicators. The final model is graphically illustrated as a figure ().

Figure 1. OR and confidence interval (95% CI) of the covariates in the final logistic regression model.

To arrive at the final simplified model, we first estimated a larger model with all independent variables deemed to be of potential statistical relevance. Insignificant covariates with the smallest effects or odds ratios (ORs) close to one were successively removed, comparing values of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) before and after the removal of a covariate. If the BIC was lower after removal of a covariate the covariate was dropped from the regression model.

All analyzes were performed by SPSS for PC version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Checklist -STROBE

We used the STROBE cross-sectional checklist when writing our report [Citation19].

Ethics

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of the South-Eastern Health Region in Norway (no. 2015/429). All patients gave written informed consent to participate.

Results

Of the 914 patients initially included in the NUCG-VII study, 715 PCa-survivors were in 2016 invited to participate in the long-term survey (Supplementary Figure 1). Finally, 431 respondents were evaluable (RP: n = 313; RT: n = 118) for this study. Low education and high-risk tumors were more frequently reported among non-evaluable patients (data not shown). There was no difference according to age between evaluable and non-evaluable men.

The mean time between RP or RT and completion of the long-term questionnaire was 7 years (). Compared to prostatectomized men, irradiated men were 4 years older and more often reported major comorbidity. The lowest EPIC-26 DSS was observed within the sexual domain, similar for both treatment modalities. A significant difference emerged for bowel function, favored prostatectomized men. Significantly more urinary incontinence appeared in the RP compared to the RT group. The majority in both groups (RP: 91%, RT: 62%) reported that their GP had mainly been responsible for PCa follow-up the past 2 years.

Table 1. Patient characteristics according to TREATMENT.

Satisfaction

Of the 431 evaluable PCa-survivors, 347 (81%) reported long-term satisfaction with their treatment (). Respondents aged 70 years or older expressed satisfaction more often than the younger ones. Major comorbidity and general health, but not the experience of PCa relapse, were significantly associated with satisfaction.

Table 2. Patient characteristics according to SATISFACTION.

Irrespective of treatment, satisfied men had higher DSSs in all five EPIC-26 domains compared to dissatisfied men (). Cohen’s coefficients indicated that these differences were relevant, most often of medium size. The largest coefficient (0.73) was observed within the sexual domain. The EPIC-26 single item scores principally confirmed the findings of the domains.

Table 3. Means (±SD) of the EPIC-26 domain summary scores and their single-item scores in patients satisfied or dissatisfied with TREATMENT.

shows frequencies and proportions of satisfied and dissatisfied PCa-survivors related to the seven Quality indicators. Overall, 273 men (65%) described sufficient follow-up in general and 251 of them were satisfied with their treatment. Among the satisfied men, 288 (84%) reported sufficient information about their treatment and 264 (77%) sufficient information about treatment options. Only 140 participants (33%) described perceived cooperation between the hospital and the responsible GP as sufficient. The majority of dissatisfied men reported insufficiency to all of the seven Quality indicators.

Table 4. Long-term satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

In the multivariable logistic regression model, the highest significant odds became evident for the Quality indicators ‘Information about treatment’ (OR 9.4) and ‘Cooperation between hospital and GP’ (OR 5.1) (). Age 70 years or older as well as sufficient information about and follow-up of AEs (ref.: insufficient) also remained significantly associated with satisfaction, together with a higher EPIC-26 score within the sexual domain. The treatment modality itself had no significant impact.

Discussion

At mean 7 years from RP or RT, four of five (81%) PCa-survivors expressed satisfaction with their treatment, though only two-thirds reported sufficient follow-up in general. In the multivariable regression model, ‘information about treatment’ remained the strongest factor associated with long-term satisfaction accompanied by the patient’s perception of sufficient ‘Cooperation between hospital and GP’. Age 70 years or older, as well as information about and follow-up of AEs, also contributed significantly to long-term satisfaction. The treatment modality itself (RP or RT) was not associated with satisfaction.

In line with previous studies, the great majority of PCa-survivors reported long-term satisfaction [Citation8–11]. Most of our respondents had during the past 2 years mainly been followed up by their GP as recommended in the Norwegian national guidelines [Citation5]. With this background, our finding of a strong association between long-term satisfaction and patient-perceived cooperation between the hospital and their GP is of importance, as well as the finding that only one-third of the men described this aspect of shared care as sufficient. Importantly, we lacked any objective data on existing interactions between the GPs and the specialist health care system. Nevertheless, the low percentage of patient-perceived sufficient cooperation leaves room for improvement. The addition of a ‘GP-dedicated’chapter in the current Norwegian national guidelines for PCa-management, is certainly a step in the right direction. Another possibility to improve this aspect is an individualized follow-up care plan provided to each patient at start of the follow-up period, accompanied by a copy to the GP. This will ensure a better, more uniform, and holistic communication between the actors: the patient, the GP and the specialist [Citation20–22]. Development of appropriate information technology which facilitates easy and ‘fast links’ between the different health care professionals, is a challenge and an opportunity, and should be prioritized [Citation20].

The importance of an individualized high-quality information, e.g., to facilitate an active patient participation in therapeutic decisions, has repeatedly been emphasized in the literature [Citation8–10, Citation21,Citation23]. Our study confirms that sufficient information through the entire PCa-pathway is essential. Use of decision aids, per internet or as flyers, in addition to consultations, may increase the patients’ experience of high-quality information [Citation24–27]. Further, use of specialized nurses may reduce the doctor’s time spent with information provided to the patient [Citation9,Citation20,Citation21,Citation28]. According to Bergengren et al., access to a ‘Nurse navigator’ was significantly associated with long-term overall satisfaction [Citation9]. In Norway, such specialized nurse practitioners are available only in hospitals, and as far as we know, not in the primary health care service.

In the univariate analyses, the levels of EPIC-26 DSSs reflected published rates of AEs after RP or RT [Citation4]. Most of our between-treatment differences (Cohen’s coefficients) were moderate, possibly explaining why the treatment modality itself, in the multivariable analysis, did not impact significantly on long-term satisfaction. Published findings are inconsistent, but the review of Christie et al. documents that the levels of regret are generally higher after RP compared to RT [Citation29]. In contrast to Bergengren et al.’s observations, persistent bowel and urinary AEs were in our study not associated with long-term satisfaction [Citation9]. Different case mix may be an explanation: Bergengren et al. included patients with the strategy ‘Active surveillance’ in their cohort in addition to prostatectomized and irradiated men. In line with Bergengren et al., an increasing DSS within the sexual domain was in our cohort positively associated with long-term satisfaction, pointing to the importance of sexuality also in elderly men.

Limitations and strengths

The fact that only one of every fourth evaluable patients had undergone RT is a limitation. Furthermore, the eight satisfaction-related questions have not been psychometrically tested only among PCa-survivors specifically. Our findings may only be relevant in health care systems with a similar follow-up strategy after RP or RT as in Scandinavia. Finally, our dichotomizations are debatable on the background of the ‘uncertain’ category and the resulting loss of information.

On the other hand, the major strength of this study is the nation-wide cohort focusing on long-term satisfaction in a GP-led shared care follow-up strategy. The use of EPIC-26, a validated questionnaire to assess treatment-related AEs after RP or RT, represents an additional strength.

Conclusion

At mean 7 years from RP or RT, the majority (81%) of curatively treated PCa-survivors, mainly followed up by their GP, reported satisfaction with their treatment. Sufficient information and improved cooperation between the hospital specialists and the responsible GP may, in addition to an optimized follow-up of AEs, further increase long-term satisfaction among prostatectomized or primary irradiated PCa-survivors.

Geolocation information

This is a nationwide study based on data delivered from patients treated at different hospitals throughout Norway.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (52.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download EPS Image (2.7 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andreas Steinsvik for providing relevant data from the NUCGVII-study. We also want to thank Siri Lothe Hess and Vigdis Opperud for support during collecting data and for layout tips of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):243–262.

- Aas K, Axcrona K, Kvåle R, et al. Ten-year mortality in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer in Norway. Urology. 2017;110:140–147.

- Stattin P, Holmberg E, Johansson JE, et al. Outcomes in localized prostate cancer: national prostate cancer register of Sweden follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(13):950–958.

- Ávila M, Patel L, López S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;66:23–44.

- Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonalt handlingsprogram med retningslinjer for diagnostikk, behandling og oppfølging av prostatakreft. 2020. Available from: https://www.helsebiblioteket.no/retningslinjer/prostatakreft/innhold

- RCC. Nationellt vårdprogram prostatacancer. 2021. Available from: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/prostatacancer/vardprogram/

- DMCG. Opfølgning af prostatacancer. 2020. Available from: https://www.dmcg.dk/Kliniske-retningslinjer/kliniske-retningslinjer/daproca/opfolgning-af-prostatacancer/

- Albkri A, Girier D, Mestre A, et al. Urinary incontinence, patient satisfaction, and decisional regret after prostate cancer treatment: a french national study. Urol Int. 2018;100(1):50–56.

- Bergengren O, Garmo H, Bratt O, et al. Satisfaction with care among men with localised prostate cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Eur Urol Oncol. 2018;1(1):37–45.

- Kretschmer A, Buchner A, Grabbert M, et al. Perioperative patient education improves long-term satisfaction rates of low-risk prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2017;35(8):1205–1212.

- Lehto US, Tenhola H, Taari K, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: a nationwide survey. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(7):864–873.

- Steinsvik EA, Axcrona K, Angelsen A, et al. Does a surgeon's annual radical prostatectomy volume predict the risk of positive surgical margins and urinary incontinence at one-year follow-up? Findings from a prospective national study. Scand J Urol. 2013;47(2):92–100.

- Storås AH, Sanda MG, Garin O, et al. A prospective study of patient reported urinary incontinence among American, Norwegian and Spanish men 1 year after prostatectomy. Asian J Urol. 2020;7(2):161–169.

- Fosså SD, Storås AH, Steinsvik EA, et al. Psychometric testing of the norwegian version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite 26-item version (EPIC-26). Scand J Urol. 2016;50(4):280–285.

- Sanda M, Wei J, Litwin M. Scoring instructions for the expanded prostate cancer index composite short form (EPIC-26). 2002. Available from: https://medicine.umich.edu/sites/default/files/content/downloads/Scoring%20Instructions%20for%20the%20EPIC%2026.pdf

- Folkehelseinstituttet. Spørreskjemabanken. 2014. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/kk/brukererfaringer/sporreskjemabanken2/

- Bjertnaes OA, Sjetne IS, Iversen HH. Overall patient satisfaction with hospitals: effects of patient-reported experiences and fulfilment of expectations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):39–46.

- Terrier JE, Masterson M, Mulhall JP, et al. Decrease in intercourse satisfaction in men who recover erections after radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2018;15(8):1133–1139.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296.

- Clarke AL, Roscoe J, Appleton R, et al. Promoting integrated care in prostate cancer through online prostate cancer-specific holistic needs assessment: a feasibility study in primary care. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(4):1817–1827.

- Appleton R, Nanton V, Roscoe J, et al. “Good care” throughout the prostate cancer pathway: perspectives of patients and health professionals. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;42:36–41.

- Hua A, Sesto ME, Zhang X, et al. Impact of survivorship care plans and planning on breast, Colon, and prostate cancer survivors in a community oncology practice. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(2):249–255.

- Reynolds BR, Bulsara C, Zeps N, et al. Exploring pathways towards improving patient experience of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP): assessing patient satisfaction and attitudes. BJU Int. 2018;121(3):33–39.

- Feldman-Stewart D, Tong C, Brundage M, et al. Prostate cancer patients’ experience and preferences for acquiring information early in their care. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018;12(5):E219–e225.

- Hacking B, Scott SE, Wallace LM, et al. Navigating healthcare: a qualitative study exploring prostate cancer patients’ and doctors’ experience of consultations using a decision-support intervention. Psychooncology. 2014;23(6):665–671.

- Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD001431.

- Violette PD, Agoritsas T, Alexander P, et al. Decision aids for localized prostate cancer treatment choice: systematic review and Meta-analysis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(3):239–251.

- Sykes J, Yates P, Langbecker D. Evaluation of the implementation of the prostate cancer specialist nurse role. Cancer Forum. 2015;39:199–203.

- Christie DR, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V. Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? A systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1002–1011.