Background

Two large randomized clinical trials (RCT), LATITUDE and STAMPEDE, demonstrated an increased overall survival by addition of the androgen receptor targeted agent abiraterone acetate to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment in men with de novo castration sensitive metastatic prostate cancer (mCSPC) [Citation1,Citation2]. In LATITUDE, the median time on treatment with abiraterone and prednisone for men with high-risk mCSPC was 26 months (inter-quartile range [IQR] 12 to 49). In STAMPEDE, the median time on treatment in the subgroup with metastatic disease, or nonmetastatic disease with no radiotherapy planned, was 33 months (IQR 14 to Not reported).

Subsidized use of abiraterone for the treatment of men with de novo mCSPC not suitable for treatment with docetaxel was approved in June 2018 in Sweden [Citation3]. Since men treated in clinical practice often are older and have more comorbidity than men in RCTs, it is relevant to study drug utilization in routine care to detect signals suggesting a potentially different effectiveness in clinical practice compared to what is expected from the efficacy estimated in the pivotal randomized controlled trials.

The aim of this study was to describe patient characteristics and time on treatment in a nation-wide population-based cohort of men with de novo mCSPC treated with abiraterone in clinical practice.

Material and methods

The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden captures 98% of all men with incident prostate cancer in Sweden compared to the Cancer Register, to which reporting is mandatory [Citation4]. In Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe) RAPID 2019 men in NPCR diagnosed with prostate cancer up to 31 December 2019 were linked to the National Patient Register and the Prescribed Drug Register [Citation5]. Data for follow-up were available until 14 December 2020. Cause of death was extracted from the Cause of Death Register and was available for men who died before 31 December 2019.

The source population for the study was men diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1 June 2018 and 31 December 2019 and who had metastases on imaging at diagnostic workup according to NPCR. Men who had a first filled prescription of abiraterone (ATC code L02BX03) in the Prescribed Drug Register within six months from diagnosis of prostate cancer were selected to the study population. Treatment initiation within six months was used as a criterion in order to restrict use of abiraterone to men with de novo mCSPC.

To contextualize the characteristics of men with mCSPC treated with abiraterone, we compared them to men receiving any other treatment than abiraterone. Baseline comorbidity was assessed by use of the Charlson comorbidity index calculated from hospital discharge diagnoses registered in the National Patient Register during a 10-year period prior to start of follow-up [Citation6,Citation7], and by use of a Drug Comorbidity Index based on the history of filled prescriptions [Citation8,Citation9].

The follow-up started on the date of the first filled prescription for abiraterone. The date for discontinuation of treatment was defined by the date of the last filling, plus the number of days covered by the prescribed amount of defined daily doses and an additional grace period of 28 days. Prescription of enzalutamide at any time after discontinuation of abiraterone was also captured from the Prescribed Drug Register, to detect a potential off-label treatment switch due to intolerance rather than disease progression. The cumulative incidence of treatment discontinuation was calculated considering death as competing risk.

In sensitivity analyses, we restricted the analysis to men who had filled a prescription for abiraterone within 90 days from prostate cancer diagnosis. In a complementary analysis, we stratified the result based on if there was an entry in the NPCR for referral for chemotherapy to an oncology department at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis. There is, however, no registration in NPCR that verifies actual administration of chemotherapy.

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Results

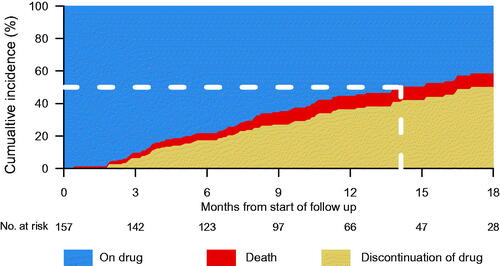

Ten percent (157 out of 1511) of men with de novo mCSPC had filled prescriptions for abiraterone between 1 June 2018 and 31 December 2019. Men whose treatment included abiraterone were younger, had higher Gleason score, higher PSA, but less comorbidity compared to men with mCSPC on standard of care defined as any other treatment as per clinical practice (). There was a fourfold difference between regions in the proportion of men with mCSPC who filled prescriptions for abiraterone. At the time of data cutoff, the median duration of follow-up was 14 months. The median time from diagnosis to first filled prescription for abiraterone was 75 days (IQR 53 to 112). The median time on treatment with abiraterone was 14 months (IQR 11 to ∞) ().

Figure 1. Stacked cumulative incidence of abiraterone treatment discontinuation and death among 157 men with de novo metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1 June 2018 and 31 December 2019 and with follow-up until 14 December 2020. Blue area: On treatment with abiraterone; Red area: Death; Light brown area: Discontinuation of abiraterone.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 1511 men in Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden RAPID 2019 diagnosed with de novo metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) from 1 June 2018 to 31 December 2019, who initiated treatment with abiraterone and prednisolone in addition to standard of care within six months from diagnosis.

Regarding the reason for discontinuation of abiraterone, we identified nine instances of treatment switch from abiraterone to enzalutamide. In total, 37 men died during follow-up, out of whom 13 died while still on abiraterone treatment. Six of these deaths occurred before data cutoff for cause of death data; five had prostate cancer and one had acute myocardial infarction as registered cause of death.

In a sensitivity analysis of men who filled a prescription for abiraterone within 90 days from diagnosis, the median time on treatment with abiraterone was 15 months (IQR 11 to ∞). Men with planned chemotherapy registered at the time of diagnosis had a longer lead time to initiation of treatment with abiraterone compared to men with no planned chemotherapy; 95 days (IQR 68 to 130) versus 70 days (IQR 50 to 101). The median time on treatment with abiraterone was the same irrespective if a referral for chemotherapy at the time of diagnosis had been registered in NPCR.

Discussion

In this drug utilization study of abiraterone for de novo metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer, covering the first 18 months after approval for subsidized use in Sweden, the median time on treatment was 14 months. The result was essentially the same in a sensitivity analysis restricting the study population to those who initiated treatment within 90 days instead of six months. There was a fourfold difference in use of abiraterone in men with mCSPC between health-care regions.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting time on treatment in clinical practice after approval of abiraterone for de novo mCSPC. We found time on treatment to be approximately half that in randomized controlled trials; 26 months in LATITUDE and 33 months in STAMPEDE [Citation1,Citation2]. LATITUDE included men with high-risk metastatic prostate cancer with two out of three of these criteria; Gleason score 8 or higher, more than three bone metastases, or visceral metastases [Citation1]. The median age at inclusion was 68 years compared to 73 years in our study, and only 2% of men had <3 foci of bone metastases compared to 14% of the men in our study. The median baseline PSA was 25 ng/ml in LATITUDE and 188 ng/ml in the Swedish cohort. A Gleason score <8 was found in 12% in our study but in only 2% in LATITUDE. The proportions with visceral disease were similar.

In STAMPEDE, men were also younger than in our study with a median age at inclusion of 67 years, but had less advanced disease; only half of the men had metastatic disease, and median PSA 53 ng/ml compared to 188 ng/ml in our study population [Citation2].

We have previously studied treatment of men with castration resistant prostate cancer using a similar design as the present study [Citation10]. The time on abiraterone was somewhat shorter in chemo-naïve men compared to the COU-AA-302 randomized trial [Citation11]; 11 versus 14 months. There was, however, no difference in the postchemotherapy setting with eight months treatment duration in our study as well as in the randomized controlled trial COU-AA-301 [Citation12]. In our current study, abiraterone was used upfront in addition to ADT as in LATITUDE and STAMPEDE. Our observation of a substantially shorter time on treatment compared with the large randomized trials on men with de novo mCSPC, but a substantially smaller difference in time on treatment for men with more advanced stages of prostate cancer (mCRPC) in our previous study [Citation10], raises the question if the magnitude of survival benefit estimated in LATITUDE and STAMPEDE for men with mCSPC will be achieved in clinical practise [Citation1,Citation2].

Men treated with abiraterone in our study population had a lower baseline comorbidity burden compared to those not treated with abiraterone. This was apparent from the difference in Charlson Comorbidity Index, but also observed in the distribution in quartiles of the more sensitive Drug Comorbidity Index [Citation8].

Strengths of our study include the high population-based coverage and reliable follow-up of men with de novo mCSPC who received abiraterone in Sweden during the first 18 months after approval for subsidized use. Our results do not suggest high mortality as a reason for the difference compared with the randomized trials. The lack of information on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/World Health Organization Performance Status (ECOG) limits our ability to compare baseline functional status to the randomized controlled trial populations. Limitations of our study also include that we did not have data on the reason for drug discontinuation. We can therefore not discriminate men who experienced disease progression from those who did not tolerate the treatment. This is an important area that we aim to explore in future studies.

There are no high-quality data on use of chemotherapy available neither in the Patient Register nor in the primary registration in NPCR. Forty-four patients were registered in NPCR by staff at the urological department as referred to the oncology department for chemotherapy. There is, however, no variable in NPCR verifying if chemotherapy was actually administered. These men filled a prescription for abiraterone within six months after diagnosis and had essentially the same time on treatment as other men who had filled a prescription for abiraterone. Our interpretation is that a majority of these men were in fact prescribed abiraterone upfront by the oncologist and did not receive chemotherapy. We cannot, however, exclude that some men initially received chemotherapy and that treatment was subsequently switched to abiraterone.

The initial experience of abiraterone treatment of men with de novo metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer in clinical practice in Sweden suggests a substantially shorter time on treatment compared to randomized controlled trials. The short time on treatment does not appear to be due to high mortality, and further studies are warranted to investigate the reasons for the shorter time on treatment in clinical practice compared to the clinical trials.

Disclaimers

Rolf Gedeborg is also employed by the Medical Products Agency (MPA) in Sweden. The MPA is a Swedish Government Agency. The views expressed in this article may not represent the views of the MPA.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.1 KB)Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR) steering group: Pär Stattin (chairman), Ingela Franck Lissbrant (co-chair), Camilla Thellenberg-Karlsson, Johan Styrke, Hampus Nugin, Eva Johansson, Magnus Törnblom, Stefan Carlsson, David Robinson, Mats Andén, Olof Ståhl, Thomas Jiborn, Hans Joelsson, Gert Malmberg, Olof Akre, Johan Stranne, Jonas Hugosson, Maria Nyberg, Per Fransson, Fredrik Jäderling, Fredrik Sandin and Karin Hellström.

Disclosure statement

Region Uppsala has, on behalf of NPCR, made agreements on subscriptions for quarterly reports from Patient-overview Prostate Cancer with Astellas, Sanofi, Janssen, and Bayer, as well as research projects with Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen. Ingela Franck Lissbrant has received speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca.

Data availability statement

Data used in the present study were extracted from the Prostate Cancer Database Sweden (PCBaSe), which is based on the National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden and linkage to several national health-data registers. The data cannot be shared publicly because the individual-level data contain potentially identifying and sensitive patient information and cannot be published due to legislation and ethical approval (https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se). Use of the data from national health-data registers is further restricted by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare (https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/) and Statistics Sweden (https://www.scb.se/en/) which are Government Agencies providing access to the linked healthcare registers. The data will be shared on reasonable request in an application made to any of the steering groups of NPCR and PCBaSe. For detailed information, please see www.npcr.se/in-english, where registration forms, manuals, and annual reports from NPCR are available alongside a full list of publications from PCBaSe. The statistical program code used for the present study analyses can be provided on request (contact [email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):686–700.

- James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):338–351.

- Fallara G, Lissbrant IF, Styrke J, et al. Rapid ascertainment of uptake of a new indication for abiraterone by use of three nationwide health care registries in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2021; 60(1):56–60.

- Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Wigertz A, et al. Cohort profile update: the national prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base-a refined prostate cancer trajectory. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(1):73–82.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–667.

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Gedeborg R, Sund M, Lambe M, et al. An aggregated comorbidity measure based on history of filled drug prescriptions: development and evaluation in two separate cohorts. Epidemiology. 2021;32(4):607–615.

- Gedeborg R, Garmo H, Robinson D, et al. Prescription-based prediction of baseline mortality risk among older men. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241439.

- Fallara G, Alverbratt C, Garmo H, et al. Time on treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide in the patient-overview prostate cancer in the national prostate cancer register of Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(12):1589–1596.

- Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138–148.

- Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):983–992.