Abstract

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus is increasing in incidence but remains a rare disease with good 3- and 5-year recurrence free and overall survival rates of 63%–86%. The treatment includes chemoradiotherapy, mainly with 5-fluoruracil (5FU) and mitomycin. The aim of this study was to describe long-term (up to 9 years after treatment) oncological outcome and the types of treatments given, in a Swedish national cohort of patients diagnosed with anal cancer between 2011 and 2013.

Method

Patients were identified in the Swedish Cancer Registry. Patients still alive were contacted and asked for consent. Clinical data were retrieved from National Patient Register at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and from medical records. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses were performed for overall survival.

Results

Three hundred and eighty-eight patients were included in the study of which 338 patients (87%) received treatment with a curative intent. Follow up was 85 months (0–113 months) for patients treated with curative intent (information missing in one patient) 7.5 months (0–55) for patients with treated with a palliative intent. Curative treatment varied and consisted of both chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy (46–64 Gy) alone. 5-FU, mitomycin and cisplatin were the most used chemotherapy agents. Five-year overall survival for patients treated with curative intent was 73%. In an adjusted analysis 5-FU and mitomycin is associated with a lower mortality than 5-FU and cisplatin but the association was weaker (HR 1.61 (95% CI: 0.904; 2.85) than in the unadjusted analysis

Conclusions

In this national cohort overall five-year survival was 73% for patients treated with curative intent. As reported by others our results indicate that 5-FU and mitomycin C should be the preferred chemotherapy in treatment for cure.

Introduction

In recent years a worldwide increase in the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus has been observed [Citation1–4]. However, it is still a rare disease with approximately 150 new cases yearly until 2015 in Sweden. In a majority of cases, the cancer is associated with Human Papilloma virus (HPV), above all high risk types HPV 16 or 18 [Citation5]. Apart from very small anal cancers where surgery might be an option, recommended primary treatment is chemoradiotherapy (CRT). Radiotherapy is often given with a total radiation dose of 50−60 Gray (Gy) and concomitant chemotherapy where fluorouracil (5-FU) in combination with mitomycin C (MMC) is considered gold standard [Citation6–8]. The prognosis is good with 3- or 5-year recurrence free and overall survival rates reported to between 63% and 86% in European and Nordic materials [Citation2,Citation9,Citation10]. In cases of incomplete remission or loco-regional recurrence patients may be considered for salvage surgery with abdomino-perineal excision (APE), after which 5-year survival rates have been reported to be 40% [Citation11,Citation12]. In the Nordic countries several treatment schedules have been developed over the last 20 years within the Nordic Anal Cancer Group (NOAC) in which most but not all centers in Sweden have been members [Citation9], but during the study period for this cohort there were no national treatment guidelines in Sweden. The aim of this study was to determine long-term (up to 9 years) oncological outcome and the types of treatments given based on data from a national cohort of patients with anal cancer treated before the development of national guidelines and before centralization of treatment in Sweden.

Material and methods

Study design

The patients were included in the ANal CAncer study (ANCA), a nation-wide longitudinal study based on a national cohort of patients diagnosed with invasive anal cancer in Sweden between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2013.

Data collection

Patients were identified through the Swedish Cancer Registry (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare). Inclusion criteria was a diagnosis of anal cancer between 2011 and 2013 registered in the Swedish Cancer Registry. Patients alive at the time for retrieval of data from the register were contacted and invited to participate and gave informed consent to retrieve clinical data and answer questionnaires at three and six years after diagnosis. For patients no longer alive only clinical data was retrieved. Clinical data was collected from the National Patient Register at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and from medical records using a standardized procedure with a pre-specified clinical record form (CRF). Tumor classification was performed according to TNM 7. Information on recurrent disease was retrieved both from medical records and from longitudinal questionnaires answered by patients (see below), any information on recurrence from either source was defined as a recurrence. Information about deaths was retrieved from the National Cause of Death Register (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare) in 2018 but additional information was added from the population register in August 2020 to achieve longer follow-up as the National Cause of Death Register has a delay in reporting. Survival was calculated as time from date of decision of treatment until death. Patients were treated at the following Oncological departments in Sweden: Göteborg, Linköping, Lund, Stockholm, Uppsala, Umeå, Örebro as well as several smaller hospitals.

Questionnaires

Through specific questionnaires patients in the ANCA study reported on socioeconomics, concurrent diseases, bodily functions and quality of life. For this analysis only data on recurrent disease were used to complement data from the clinical record.

Statistical analysis

As this was mainly a descriptive study no formal power calculation was performed. Survival among the three groups (chemoradiotherapy with fluorouracil (5-FU) in combination with mitomycin C, chemoradiotherapy with 5-FU in combination with cisplatin and radiotherapy alone) was characterized by Kaplan-Meier curves where follow-up time was from date of decision of treatment to retrieval from the population registry in August 2020. Only patients treated with a curative intent were included in this analysis. Mortality was analyzed using a Cox proportional hazard model where adjustment was made for factors considered to be confounders: age, cardiovascular disease (yes, no), tumor stage, comorbidity (yes if at least one of the following conditions was present: diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, renal dysfunction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma or HIV. Age was standardized (subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation) and included in the model as a natural cubic spline with three knots to allow for a non-linear relationship between age and outcome. Proportional hazards assumption was assessed by global test based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Results are presented as hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Follow-up for recurrence was at least three years (some patients did not enter dates for recurrence in their questionnaire and in some cases clinical follow-up was not complete for the entire study period). The level of statistical significance was set to 5%. No correction for multiplicity was performed. Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test were used to highlight potential differences between the different treatment groups. Statistical calculations were performed using R software version 4.1.0.

Ethical aspects

The ANCA study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (EPN) in Gothenburg. (Dnr. 495-15). The study was registered at Clinical Trials NCT02546973.

Results

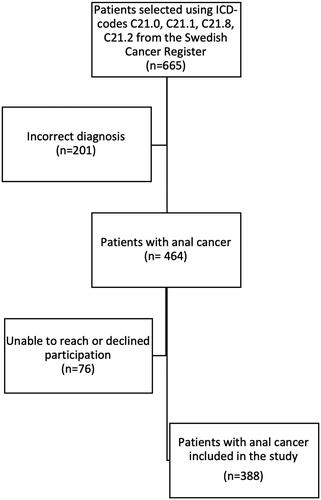

In total, 665 patients with the diagnosis of anal cancer were identified from the Swedish Cancer Registry using the following ICD-10 codes: C21.0, C21.1, C21.8, and C21.2. Two hundred and one patients were excluded due to incorrect diagnosis and 76 patients still alive could not be reached or declined participation, thus 388 patients were included in the study (). Three hundred and thirty-nine patients (87%) were treated in one of the seven university hospitals: Göteborg (85), Linköping (36), Lund (57) Stockholm (93), Uppsala (35), Umeå (21) and Örebro (12). Forty-nine patients were treated in other hospitals.

Figure 1. Flowchart over study inclusion. Patients were identified in the Swedish Cancer registry. In the registry anal intraepithelial dysplasias III is registered as well, accounting for many of the incorrect diagnoses.

Demography is displayed in . A majority were female 281/388 (72%) and the most common form of comorbidity; hypertension was present in 114/387 (29%). Mean age was 67 years. Seventy-two percent (283/388) of the patients were diagnosed with UICC stage II or III anal cancer. Treatment was given with curative intent to 87% of patients and 11% of the patients were treated with palliative intent. All treatment decisions were taken at the treating hospital. For some patients the intent of treatment was not possible to determine from the medical record (n = 6).

Table 1. Demography and patient characteristics.

Curative treatment (n = 338) consisted for 221 of patients of primary chemoradiotherapy of whom a majority received concomitant chemotherapy, most commonly 5-FU in combination with mitomycin C (FuMi). One third of patients received induction chemotherapy, mainly 5-FU in combination with cisplatin, followed by radiotherapy. More men than women and patients with more advanced tumors received cisplatin compared to patients receiving mitomycin. For patients treated with chemoradiotherapy, total doses to the primary tumor ranged between 46 and 64 Gy (see ). The fractions were 2 Gy for 277 patients, with a range of 1.8–4.3 Gy. Approximately one third of patients treated with curative intent received radiotherapy alone, with total doses to the primary tumor between 46 and 68 Gy. Most patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) or volumetric-modulated radiation therapy (VMAT) and one fourth of the patients received 3D-conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT).

Sixteen patients were treated with surgery as primary treatment, of which four were operated with an abdominoperineal excision due to previous pelvic radiotherapy.

A pretherapeutic colostomy was performed in 64 patients (52 patients with a curative intent), of whom 3 were operated as an emergency case. The reason for a colostomy were: bleeding (4), evacuation difficulties (24), fecal incontinence (13) and unknown or other causes (22) (missing data on 7 patients).

Twenty-eight patients were operated with an abominoperinal excision (28/364, 8% (missing data on 24 patients)), of which six were operated as primary treatment.

For patients treated with palliative intent radiotherapy alone and best supportive care were the most common treatment options ().

Mortality and recurrent disease

Patients were followed from date for decision of treatment to date of death or end of follow-up in August 2020, with a median follow-up of 85 months (0–113 months) for patients treated with curative intent (information missing in one patient) 7.5 months (0–55) for patients with treated with a palliative intent. During the follow-up period of up to nine years 161 patients died (41.5%).

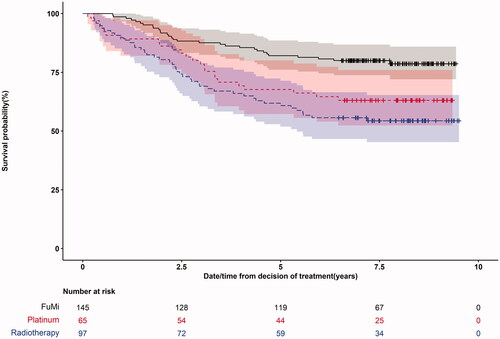

Five-year overall survival for patients treated with curative intent was 73% (95% CI:68%; 78%). Among patients with curative intent, being treated with 5-FU in combination with cisplatin was associated with higher mortality compared to 5-FU in combination with mitomycin C Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.94 (95% CI:1.13;3.34) (). Chemoradiotherapy with 5-FU in combination with mitomycin C was associated with a lower mortality compared to radiotherapy alone HR 2.63 (95%CI: 1.65;4.18). In an adjusted analysis 5-FU and mitomycin was associated with a lower mortality than 5-FU with cisplatin but the association was weaker (HR 1.61 (95% CI: 0.904;2.85). Survival curves show that chemoradiotherapy is superior to radiotherapy ().

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier graph showing the difference in survival for curative patients between the three curative treatment groups: 5-FU and Mitomycin C, Platinum based therapy and Radiotherapy alone.

Adjusted five-year overall survival differed between the three curative treatment groups: 5-FU and Mitomycin C 90% (95% CI:84%; 97%), 5-FU and cisplatin 85% (95% CI:74%; 97%) and Radiotherapy 73% (95% CI: 60%; 90%) ().

Table 2. Cox regression overall survival.

Recurrence was detected in 77/348 (22%) patients (data missing for 40 patients), and of these 37 patients had local recurrence only (For 6 patients details on the localization of the recurrence was uncertain).

Discussion

In this study of a national cohort of patients treated for anal cancer before national treatment guidelines we found a five-year overall survival of 73% and recurrence in 22% of patients after a median of seven years of follow-up. The most used curative treatment was a combination of radiotherapy and concurrent 5-FU plus mitomycin.

Our results are in line with results from previous Nordic studies. In a national Norwegian cohort treated between 1987 and 2016, the 5-year net survival was 76% [Citation2]. In a national Norwegian cohort treated between 2000 and 2007, overall five year survival was 66% [Citation13]. In a later Norwegian cohort, treated between 2013 and 2017, five-year survival rates were higher with OS at 86% [Citation10].

A Scandinavian cohort with shorter follow-up, reported 3-year recurrence-free survival ranging from 63% to 76% [Citation9]. Even though our cohort indicated a higher rate of distant metastases, survival rates were comparable or higher, which is interesting and may indicate that disease progression can be slow even with distant metastases [Citation9,Citation13]. It could also be attributed to different treatment strategies for metastatic disease. The accrual period was short, 2011–2013, but we found a diversity of treatment protocols, both regarding radiation doses and chemotherapy regimens used. Also, almost 12% of patients were treated at institutions with a small yearly caseload, centers not included in previous studies from Scandinavia. Also, a decade ago, most hospitals participating in the treatment of anal cancer did not have formal multidisciplinary meetings. Since the centralization of care for anal cancer in Sweden in 2017, all patients are discussed at a national multidisciplinary conference.

Chemoradiotherapy is considered as standard treatment for anal cancer since more than two decades [Citation6,Citation7,Citation14,Citation15]. In this cohort, a surprisingly large fraction of patients treated with curative intent still received radiotherapy alone without the addition of chemotherapy. Even though comorbidity was more common in the group that received radiotherapy without chemotherapy, the medical records did not reveal obvious reasons for the choice of treatment in all cases. Treatment with radiotherapy alone was associated with poorer survival compared with patients treated with chemoradiotherapy, irrespective of chemotherapy regimen, supporting the addition of chemotherapy in the treatment for all patients with curative intent.

A survival benefit, although not statistically significant in adjusted analyses, for patients receiving 5-FU combined with mitomycin compared with 5-FU combined with platinum-based therapy was observed. In previous randomized controlled trials comparing chemoradiation with 5-FU and mitomycin to 5-FU and cisplatin, a statistically significant difference has been reported for disease-free survival where 5-FU and mitomycin was advantageous [Citation16], and significant differences have also been reported for overall survival [Citation16,Citation17]. Although not significant in adjusted analysis, our findings support the current international guidelines on 5-FU combined with mitomycin as gold standard [Citation8].

The variety of treatment regimens used probably reflects treatment being given at many centers as well as lack of national guidelines at that time and possibly also the lack of multidisciplinary meetings. To date it can only be speculated but seems probable that the national guidelines now in place may improve outcome, as adherence to guidelines in for example breast cancer has been shown to improve oncologic outcome [Citation18]. However, the effect of guidelines will be difficult to separate from centralization of anal cancer treatment in Sweden from 2017.

This study has several strengths, firstly in being a national cohort, including low volume centers and with only 11% of the total number of patients missing making data generalizable. Another strength is the long-term follow-up of a recent cohort. The data were collected both from medical records and through detailed patient reported questionnaires with high response rates, probably rendering more comprehensive data. In addition, we used a pre-specified clinical record form and one of the authors (AA) made a quality control of data retrieved from the medical records.

One limitation of this study was the retrospective collection of data where not all information on treatment intent as well as details on the rationale behind treatment decisions could be elucidated. Another limitation was that HPV status was not yet in routine use in health care at the time of the study. It is possible that including such information in the analysis of overall survival could have improved the understanding of our results. The cohort finally included 89% of all possible patients, which could be argued to be a limitation but in fact is a high percentage for a national study. However, it is reasonable to assume that at three years after onset, the missing patients could have severe concomitant and recurrent disease. The high number of cases with incorrect diagnosis, retrieved from the National patient/cancer register, was due to the coding by ICD 10, where premalignant tumors are included in the codes.

Conclusions

In conclusion we found that survival after a diagnosis of anal cancer in Sweden was as expected although treatment was diversified and decentralized.

As many patients in this cohort received treatment that today may be considered insufficient, the survival is likely to improve further with the treatment guidelines used today.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.3 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research with large questionnaires, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Islami F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):924–938.

- Guren MG, Aagnes B, Nygard M, et al. Rising incidence and improved survival of anal squamous cell carcinoma in Norway, 1987–2016. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18(1):e96–e103.

- Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, et al. Incidence trends and burden of human Papillomavirus-associated cancers among women in the United States, 2001–2017. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):792–796.

- Kang YJ, Smith M, Canfell K. Anal cancer in high-income countries: increasing burden of disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205105.

- Bjorge T, Engeland A, Luostarinen T, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for anal and perianal skin cancer in a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2002; 87(1):61–64.

- Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014; 40(10):1165–1176.

- Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. UKCCCR anal cancer trial working party. UK Co-ordinating committee on cancer research. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1049–1054.

- Werner RN, Gaskins M, Avila Valle G, et al. State of the art treatment for stage I to III anal squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2021;157:188–196.

- Leon O, Guren M, Hagberg O, et al. Anal carcinoma - survival and recurrence in a large cohort of patients treated according to Nordic guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113(3):352–358.

- Slørdahl KS, Klotz D, Olsen J, et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(7):921–930.

- Hagemans JAW, Blinde SE, Nuyttens JJ, et al. Salvage abdominoperineal resection for squamous cell anal cancer: a 30-year single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(7):1970–1979.

- Nilsson PJ, Svensson C, Goldman S, et al. Salvage abdominoperineal resection in anal epidermoid cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(11):1425–1429.

- Bentzen AG, Guren MG, Wanderas EH, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of anal carcinoma: survival and recurrence in an unselected national cohort. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012; Jun 183(2):e173–e180.

- Bosset JF, Pavy JJ, Roelofsen F, et al. Combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy for anal cancer. EORTC radiotherapy and gastrointestinal cooperative groups. Lancet. 1997;349(9046):205–206.

- Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer radiotherapy and gastrointestinal cooperative groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):2040–2049.

- Gunderson LL, Winter KA, Ajani JA, et al. Long-term update of US GI intergroup RTOG 98-11 phase III trial for anal carcinoma: survival, relapse, and colostomy failure with concurrent chemoradiation involving fluorouracil/mitomycin versus fluorouracil/cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4344–4351.

- James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(6):516–524.

- Ricci-Cabello I, Vasquez-Mejia A, Canelo-Aybar C, et al. Adherence to breast cancer guidelines is associated with better survival outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies in EU countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):920.