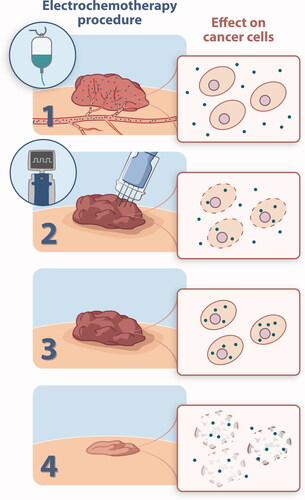

Electrochemotherapy (ECT) is a treatment method, which uses electroporation to permeabilize the cell membrane and improve the delivery of chemotherapy into cells, thus increasing the cytotoxic effect several hundred fold [Citation1–3] (). ECT was first described in the early 1990s [Citation4] and is an established treatment option for primary and secondary cutaneous malignancies. The treatment was standardised in 2006 and updated in 2018 [Citation5,Citation6] and is now implemented in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) melanoma guidelines [Citation7,Citation8]. Over the past 30 years, ECT has been proven to have high and consistent overall tumour response (OR) and is performed in many cancer centres across Europe [Citation9–11].

Figure 1. (1) Cutaneous tumours are identified for treatment and bleomycin is injected either intravenously (many or large tumours) or intratumourally. Bleomycin does not easily pass the cell membrane due to its hydrophilic and charged nature. (2) Electric pulses (400 V, 8 pulses of 0.1 ms) are applied to the tumour area, these pulses cause permeabilization of the cell membrane, thus allowing entry of bleomycin to the cell interior. The electrode is moved to cover the entire tumour volume with margins. (3) Bleomycin is now intracellular and can exert single and double strand DNA breaks, the cytotoxicity being enhanced several hundred fold after internalization. (4) Cell death ensues, most patients are treated only once due to the high efficacy.

Treating malignant melanoma metastases is one of the most common indications for ECT, comprising one third of cases treated with the method [Citation11]. ECT is used for cutaneous metastases when systemic treatments fail to provide long-term responses or metastases are deemed inoperable. Melanoma metastases often present a surgical challenge and are considered unresectable if they present in high numbers, with bulky growth or rapid recurrence. Other local treatment strategies include radiotherapy, isolated limb perfusion and intra-lesional injection of cytotoxic drugs [Citation12]. ECT has the advantage of being applicable all over the surface of the body and head and neck area, showing high response rates across different tumour subtypes [Citation11]. If a patient has few, smaller lesions, the treatment can be performed with local anaesthesia.

As ECT is commonly used in patients with disseminated disease, the treatment is often palliative – helping patients with symptomatic or cosmetically distressing cutaneous lesions. Since ECT is by default a once-only treatment, it can easily be implemented in treatment plans for melanoma patients.

In this issue of Acta Oncologica, Petrelli and colleagues present an extensive and up-to-date review and meta-analysis of all data on ECT for the treatment of superficially metastatic melanoma [Citation13]. The review found a pooled OR of 77.6%, similar to the OR of 82% in patients with malignant melanoma observed by Clover et al. in a large prospective European study of ECT for cutaneous tumours [Citation11], confirming a very high response rate.

A palliative treatment like ECT needs definition of treatment toxicity, response after retreatment, local control and patient-reported outcomes. Here, the Petrelli study makes an effort to give a comprehensive evaluation of ECT for malignant melanoma metastases to skin, including duration of response. Petrelli and colleagues emphasise that data on these parameters are challenging to obtain but nonetheless imperative. This knowledge is essential for evaluating the influence of ECT on quality of life for patients with cutaneous metastases, an area that lacks data and is largely overlooked. Petrelli et al.’s review also highlights the variation in reporting of current ECT literature. Altogether they confirm the favourable oncologic outcomes of ECT in the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma, however some parameters are yet to be established in order to properly evaluate palliative treatments, e.g., extension of treatment field, inclusion of treatment margins and frequency of treatment [Citation13].

With the compelling response rates seen with ECT along with the great advances this past decade in precision medicine (e.g., Ipilimumab, PD-1- and BRAF inhibitors), further investigation of ECT in combination with these therapies is encouraged. Such studies could include malignant melanoma metastases, or even primary melanomas if surgical excision would cause severe disfigurement or disability and the patient is duly informed of standard treatments. Using ECT to limit surgical resections that require amputation could potentially allow limb-sparing surgery for melanoma patients and new opportunities for disease management in complex patients. An increased response and overall survival when using ECT in combination with immunotherapy for the treatment of malignant melanoma (e.g., Ipilimumab) has already been reported [Citation14]. Petrelli and colleagues mention the possibility of combining local and systemic treatment, thereby maximising the long-term benefit of ECT. They therefore conclude that future studies should aim to enrol as homogenous populations as possible, to better delineate subgroups most likely to benefit from treatment and define the most effective treatment protocols [Citation13]. A unique feature of ECT is a similarly high response rate across tumour histologies. Thus, any experience from treatment of malignant melanoma metastases is valuable for palliative treatment of patients with skin metastases, not only from malignant melanoma but from all tumour subtypes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Orlowski S, Belehradek J, Jr., Paoletti C, et al. Transient electropermeabilization of cells in culture. Increase of the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37(24):4727–4733.

- Gehl J, Skovsgaard T, Mir LM. Enhancement of cytotoxicity by electropermeabilization: an improved method for screening drugs. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9(4):319–325.

- Jaroszeski MJ, Dang V, Pottinger C, et al. Toxicity of anticancer agents mediated by electroporation in vitro. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11(3):201–208.

- Belehradek M, Domenge C, Luboinski B, et al. Electrochemotherapy, a new antitumor treatment. First clinical phase I-II trial. Cancer. 1993;72(12):3694–3700.

- Mir LM, Gehl J, Sersa G, et al. Standard operating procedures of the electrochemotherapy: Instructions for the use of bleomycin or cisplatin administered either systemically or locally and electric pulses delivered by the CliniporatorTM by means of invasive or non-invasive electrodes. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2006;4(11):14–25.

- Gehl J, Sersa G, Matthiessen LW, et al. Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(7):874–882.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Electrochemotherapy for metastases in the skin from tumours of non-skin origin and melanoma; 2013. Available from: http://publicationsniceorguk/electrochemotherapy-for-metastases-in-the-skin-from-tumours-of-non-skin-origin-and-melanoma-ipg446

- Michielin O, van Akkooi A, Lorigan P, et al. ESMO consensus conference recommendations on the management of locoregional melanoma: under the auspices of the ESMO guidelines committee. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(11):1449–1461.

- Gothelf A, Mir LM, Gehl J. Electrochemotherapy: results of cancer treatment using enhanced delivery of bleomycin by electroporation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29(5):371–387.

- Seyed Jafari SM, Jabbary Lak F, Gazdhar A, et al. Application of electrochemotherapy in the management of primary and metastatic cutaneous malignant tumours: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(3):287–313.

- Clover AJP, de Terlizzi F, Bertino G, et al. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous malignancy: outcomes and subgroup analysis from the cumulative results from the pan-European international network for sharing practice in electrochemotherapy database for 2482 lesions in 987 patients (2008–2019). Eur J Cancer. 2020;138:30–40.

- Dossett LA, Ben-Shabat I, Olofsson Bagge R, et al. Clinical response and regional toxicity following isolated limb infusion compared with isolated limb perfusion for in-transit melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(7):2330–2335.

- Petrelli F, Ghidini A, Simioni A, et al. Impact of electrochemotherapy in metastatic cutaneous melanoma: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2021;10:1–12.

- Heppt MV, Eigentler TK, Kahler KC, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade with concurrent electrochemotherapy in advanced melanoma: a retrospective multicenter analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(8):951–959.