Introduction

Osimertinib is a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). It is currently approved for the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose tumors exhibit specific mutations as either adjuvant, first-line, or second-line treatment. First and second-generation EGFR-TKI’s, (erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, and others), are well known for inducing cutaneous toxicities. The pathogenesis of these toxicities is attributed to EGFR inhibition, as EGFR is widely expressed in the basal cell layer of the epidermis, hair follicles, sebaceous and sweat glands, and periungual tissue. Consequently, blocking EGFR leads to the disturbance of epidermal homeostasis and the development of cutaneous pathologies [Citation1].

First and second-generation EGFR-TKI’s most commonly cause papulopustular acneiform rash, pruritus, and nail toxicities. Typically, cutaneous toxicities from EGFR-TKI’s are low grade (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Grade 1-2) but reports of severe grades have been recorded and have led to dose modification or interruption of cancer treatment [Citation1]. Currently, less literature exists describing cutaneous toxicities from third-generation EGFR-TKI’s, like osimertinib. With informed consent from the patient, we present a case of Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans (EDP) occurring during osimertinib treatment. To our knowledge, this is the second case of de-novo pigmentary change secondary to a third-generation EGFR-TKI reported [Citation2].

Case report

A 52-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to the outpatient oncodermatology clinic for dyschromia on bilateral arms for ‘several months’. Two and half years prior, the patient was diagnosed with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, which had metastasized to the spine, brain, and liver at the time of diagnosis. Her tumor was found to be positive for an EGFR exon 19 deletion. Upon tumor genotyping, a decision to initiate osimertinib was made. Two weeks after initiation, she developed a transient Grade 1 acneiform rash localized to her chest and face which did not necessitate treatment. After three months of treatment, marked improvement of metastases in the brain and liver were noted. At 8 months, her treatment course was complicated by new bilateral lung ground-glass opacities concerning for interstitial lung disease (ILD) thought to be associated with EGFR-TKI treatment [Citation3]. The decision was made to hold osimertinib for one month which improved pulmonary CT findings, and it was restarted cautiously without any further respiratory symptoms. Additional cancer treatments included two doses of palliative radiation therapy to the patient’s spine one month and two years after initial diagnosis. Other medications include denosumab indicated for hypercalcemia of malignancy and pain medications (oxycodone, acetaminophen, and gabapentin). No new topical agents were introduced before or during this period.

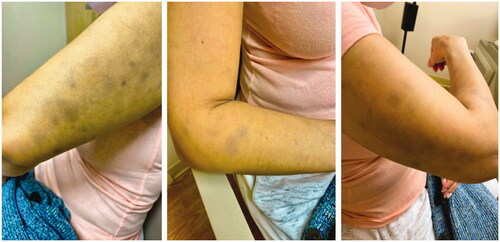

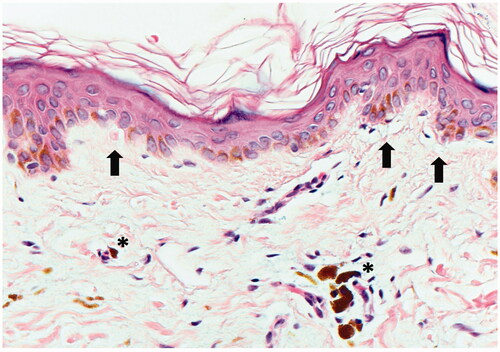

At the time of her initial visit to dermatology, the patient had been taking osimertinib, along with the same medications listed above, for two and half years with excellent treatment response. The patient noted progressive skin discoloration on her upper arms for months, without any associated symptoms. Physical exam was notable for multiple, distinct, ill-defined blue-gray pigmented macules and patches on her bilateral upper outer arms and forearms (). The differential diagnosis considered was Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) vs. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP) vs. Drug-induced pigmentation. A punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed hyperkeratosis, with a vacuolar interface at the dermo-epidermal junction. There were necrotic keratinocytes also present. The dermis contained a superficial perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate that contained lymphocytes, histiocytes, and macrophages with brown pigment that was consistent with melanin (). The biopsy was interpreted as subtle interface dermatitis with post-inflammatory pigmentary alteration, which has a broad differential diagnosis. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and an extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) panel were negative, ruling out a connective tissue disease. Based on clinco-pathologic correlation and the clinical history, a diagnosis of EDP secondary to osimertinib was made. Triamcinolone 0.1% ointment was prescribed but did not result in cosmetic improvement.

Figure 1. Patient’s bilateral upper outer arms and forearms with distinct, ill-defined, blue-gray pigmented macules and patches.

Figure 2. A punch biopsy of the right upper arm shows a subtle vacuolar interface with vacuolar changes and necrotic keratinocytes (black arrows). Perivascular inflammation is present and dermal melanophages (asterisks) are seen (Hematoxylin and Eosin, 400x).

Unfortunately, three months after her initial dermatology appointment the patient’s cancer progressed, and therefore her treatment with osimertinib was discontinued and she was started on a combination of pembrolizumab, pemetrexed, and carboplatin. Since then, the patient has not returned to dermatology for follow-up.

Discussion

Cutaneous toxicities secondary to third-generation EGFR-TKI’s are less common than with first or second-generation EGFR-TKI’s. In one study comparing first and second-generation TKI’s to osimertinib, cutaneous toxicities were observed at a lower rate in patients on osimertinib [Citation1]. The decreased rates of cutaneous toxicities are likely because osimertinib inhibits, amongst other mutations, mutant EGFR (T790), as opposed to wild-type EGFR [Citation4]. However, despite their decreased incidence, cutaneous toxicities due to third-generation EGFR-TKI’s can be symptomatic and necessitate clinical assessment. In one study, mavelertinib (a third-generation EGFR-TKI), caused up to 30% of participants to experience a CTCAE Grade 3 skin toxicity, when given a dose of >150 mg [Citation5]. In a phase II study of osimertinib, generalized rash was seen in 34%, xerosis in 23%, and, paronychia in 22% of study patients. Additionally, a few case studies describing cutaneous toxicities from osimertinib have been published. A case series in 2018 described ‘cut-like lesions’ on the fingertips of two patients taking osimertinib. Three cases of Toxic epidermal necrolysis/Stevens-Johnson syndrome after initiation of osimertinib have been recorded in patients of Asian descent [Citation6]. Cutaneous vasculitis and exacerbation of subacute cutaneous lupus (SCLE) secondary to osimertinib have been recently reported [Citation7,Citation8]. Dual therapy of osimertinib and ramucirumab (a VEGF-R inhibitor) has been shown to induce the growth of pyogenic granulomas [Citation9].

Pigmentary changes secondary to EGFR-TKI’s have been reported rarely and have been attributed to post-inflammatory changes. To our knowledge, this report represents the second case of new-onset pigmentary changes due to osimertinib in the published literature [Citation2]. Combining clinical and histologic evidence, a diagnosis of EDP was established. However, LPP was another diagnosis considered, and thus it is important to explore and clarify the differences that exist between the two similar cutaneous pigmentary pathologies.

Historically, it has been debated whether LPP and EDP are distinct pathologies or are variants of the same underlying disease. A recent global consensus statement was released in which EDP and LPP were established as two separate diseases with subtle histological and clinical differences [Citation10]. Epidemiologically, EDP has a stronger female predominance while LPP exists equally amongst males and females. Both diseases are mostly seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III-V, but EDP typically occurs in patients of Latin descent, like our patient, with a lighter skin type than LPP which is primarily seen in patients of Indian descent with more pigmented skin types [Citation11]. In terms of pathogenesis, LPP is thought to be caused by an aberrant immune response in which CD8+ T-cells attack epidermal keratinocytes inducing pigmentary incontinence [Citation12]. EDP’s etiology is thought to be caused by an abnormal immune response to antigens with elevated levels of CD8+ T-cells in the dermal layer and HLA-DR + keratinocytes in the epidermal layer [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14].

Clinically, EDP presents with blue-gray macules, with some lesions showing an erythematous border, symmetrically distributed on the trunk and extremities. LPP’s macules are characterized as dark brown and are typically seen on photo-exposed areas like the face and neck, often starting on the temples and preauricular areas [Citation11]. In both conditions, histopathology is characterized by basal vacuolization along the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ), superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, and the presence of melanophages in the upper dermis. In LPP, however, epidermal changes like hypergranulosis and hyperkeratosis are commonly also seen. In one review, EDP cases showed a higher frequency of lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and melanophages [Citation11]. Given our patient’s ethnicity, lesion morphology, and distribution of blue-gray macules on bilateral arms, the diagnosis was most consistent with EDP compared to LPP. Standardized treatment for EDP does not exist. For limited disease, topical treatment options may include mid to high potency topical steroids, tacrolimus, skin lightening creams, and tretinoin with minimal improvement. In some studies, clofazimine was shown to be effective, but the accompanying side effects were intolerable to participants [Citation11].

Our goal in presenting this case is to broaden the collection of known cutaneous effects of EGFR-TKI’s.

This case is valuable as it illustrates a rare, pigmentary disease occurring secondary to a third-generation EGFR-TKI. This report differs from the first case report published as our patient was taking osimertinib for over two years before the development of EDP, as opposed to a shorter period of six months reported in the first case report [Citation2]. As this condition is benign and the therapeutic potential of osimertinib is promising, it is important to weigh the risk-benefit analysis of ceasing or reducing the medication in response to this cutaneous effect. Standardized treatment options for EDP and LPP have yet to be established, but we hope our report encourages continued efforts in defining effective treatment.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Chu CY, Choi J, Eaby-Sandy B, et al. Osimertinib: a novel dermatologic adverse event profile in patients with lung cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(8):891–899.

- Lertpichitkul P, Wititsuwannakul J, Asawanonda P, et al. Osimertinib-associated ashy dermatosis-like hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(2):86–88.

- Fan M, Mo T, Shen L, et al. Osimertinib-induced severe interstitial lung disease: a case report. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(7):1657–1660.

- Yi L, Fan J, Qian R, et al. Efficacy and safety of osimertinib in treating EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC: a Meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(1):284–294.

- Murtuza A, Bulbul A, Shen JP, et al. Novel Third-Generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(4):689–698.

- Sato I, Mizuno H, Kataoka N, et al. Osimertinib-Associated toxic epidermal necrolysis in a lung cancer patient harboring an EGFR Mutation-A case report and a review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(8):403.

- Hamada K, Oishi K, Okita T, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis induced by osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(12):2188–2189.

- Ferro A, Filoni A, Pavan A, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus Erythematosus-Like eruption induced by EGFR -Tyrosine kinase inhibitor in EGFR-Mutated non-small cell lung cancer: a case report. Front Med. 2021;8:570921.

- Daze RP, Dinkins J, Mahoney MH. Osimertinib and ramucirumab induced pyogenic granulomas: a possible synergistic effect of dual oncologic therapy. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15076.

- Kumarasinghe SPW, Pandya A, Chandran V, et al. A global consensus statement on ashy dermatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation, and riehl's melanosis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(3):263–272.

- Leung N, Oliveira M, Selim MA, et al. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a case report and systematic review of histologic presentation and treatment. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(4):216–222.

- Robles-Mendez JC, Rizo-Frias P, Herz-Ruelas ME, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and its variants: review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(5):505–514.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(3):325–329.

- Pinkus H. Lichenoid tissue reactions. A speculative review of the clinical spectrum of epidermal basal cell damage with special reference to erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107(6):840–846.