Abstract

Aim

The prognosis for local recurrence after rectal cancer treatment is poor. A minority of patients are eligible for surgery with curative intent, which could possibly be improved by earlier detection. The aim of this study was to determine symptoms at presentation and how local recurrence was diagnosed, and to identify alarm symptoms for local recurrence as opposed to symptoms found among patients after surgery for rectal cancer in general.

Methods

In a population-based retrospective cohort (cohort A), all patients who had undergone resection surgery for rectal cancer in the region of Västra Götaland, Sweden, diagnosed 2010–2014, were identified through the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry. After a follow-up period of at least five years, medical records were reviewed to identify patients diagnosed with local recurrence. Data on symptoms, diagnostic procedures and treatment of local recurrence were retrieved. A prospective cohort of patients who had undergone surgery for rectal cancer without local recurrence (the QoLiRECT-study, cohort B) was used for comparison regarding symptoms at two years after treatment.

Results

Cohort A consisted of 1208 patients, out of whom 78 (6%) were diagnosed with local recurrence. Forty-six patients were diagnosed between scheduled follow-up visits. Fifty-eight patients were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, and the most common symptoms were pain, bleeding and urogenital symptoms. Pain was more common in patients with local recurrence when comparing cohort A with cohort B.

Conclusion

A majority of patients with local recurrence were diagnosed outside of the scheduled follow-up. Most of the patients were symptomatic at diagnosis. Symptoms were common in patients after rectal cancer surgery in general, however pain was more common in patients with local recurrence and could represent an alarm symptom.

Introduction

Local recurrence is a feared outcome after treatment for rectal cancer, often associated with considerable suffering for the patients [Citation1,Citation2]. Radical surgical resection is considered the only possible cure for local recurrence, but this is achievable for only a minority of patients with local recurrence, and overall, the prognosis is poor [Citation3–6]. Early detection of local recurrence could possibly increase the proportion of patients available for surgery with curative intent [Citation7–10], however it has not been shown to result in better prognosis [Citation7,Citation9–12].

The incidence of local recurrence of rectal cancer has decreased substantially in the last 30–40 years, mainly due to preoperative radiotherapy and improvement of surgical technique with the introduction of total mesorectal excision (TME) [Citation13–17]. From rates as high as 20–40%, local recurrence is now down to 5–10% [Citation13,Citation18,Citation19]. However, as rectal cancer is a common disease affecting more than 700 000 individuals annually worldwide [Citation20], many patients will still suffer from local recurrence.

Improved survival through detection and treatment of local recurrence and distant metastases is the main purpose of scheduled follow-up after rectal cancer surgery [Citation21]. Local recurrence can be diagnosed by various methods: clinical examination, endoscopy and/or radiographic imaging such as computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [Citation7,Citation21]. Previous studies have indicated that the value of routine rectoscopy in diagnosing local recurrence is limited [Citation22,Citation23]. Current Swedish national guidelines for colorectal cancer suggest follow-up with CT thorax and abdomen, CEA, and rectoscopy for patients with remaining rectum, at one and three years postoperatively [Citation24]. The frequency and examination modality for postoperative surveillance has been investigated, but needs to be re-considered as diagnostic tools evolve. Blood samples such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) have not yet been found sufficiently helpful [Citation25,Citation26], but perhaps in the future circulating DNA (“liquid biopsies”) might be a useful tool [Citation27,Citation28].

The aim of this study was to determine symptoms at diagnosis of local recurrence of rectal cancer as well as diagnostic modalities used to establish the diagnosis, and to compare the occurrence of symptoms in patients with local recurrence with symptoms in patients two years after treatment for rectal cancer without local recurrence, to identify possible alarm symptoms indicating local recurrence that should prompt workup.

Methods

Overall study design

A retrospective population-based cohort (Cohort A) was used to study symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and outcome of treatment for local recurrence. A reference population of patients who had undergone surgery for rectal cancer was identified in the Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer (QoLiRECT) study (Cohort B), and symptoms were compared.

Cohort A - study population and data collection

A retrospective population-based cohort identifying all patients diagnosed with rectal cancer in the region of Västra Götaland, Sweden, during the period 2010-2014, through the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR). This is a national registry with a coverage rate of 98.5% [Citation29]. From the SCRCR data were retrieved including preoperative evaluation, neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy, surgical treatment and pathological examination. Patients who did not undergo surgery with abdominal tumour resection were excluded. A retrospective review of the medical records at least five years after treatment for all patients who underwent resection surgery was conducted. Data on local recurrence, metastases, and diagnosis, symptoms, treatment and outcome of the locally recurrent disease were retrieved using a predefined clinical record form (CRF).

Cohort B (QoLiRECT) - study population and data collection

Cohort B was identified from the two-year follow-up of the QoLiRECT study, a prospective longitudinal observational multicenter study focussing on functional impairment and quality of life in patients with rectal cancer [Citation30]. The study included patients with biopsy verified rectal cancer in 16 hospitals in Sweden and Denmark during 2012 to 2015. Patients were included at the time of diagnosis, and filled in questionnaires at baseline and at one, two and five years following diagnosis [Citation30], and clinical data were retrieved from the Swedish and Danish ColoRectal Cancer Registries. In the current study, patients with local recurrence at the time of the two-year follow-up, and patients with local recurrence at any point who were also included in cohort A, were excluded from cohort B to form a local recurrence free group as comparison. Data on pain and urogenital symptoms were retrieved from the QoLiRECT-study at two-year follow-up. Data on pain in the abdominopelvic region was obtained from the markings on the pain drawing from the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form included in the questionnaire [Citation31]. Urogenital symptoms were derived from the responses to questions regarding urinary function in the last month including evacuation problems, urgency and incontinence, and questions about vaginal bleeding and discharge, combined into one variable. An affirmative answer to one of these questions, regardless of the frequency with which the symptoms occurred, was considered as presence of urogenital symptoms. Two years was chosen to mimic the median time from surgery to local recurrence as described in several other studies [Citation2,Citation32].

Definitions

Local recurrence of rectal cancer in cohort A was defined as tumour recurrence within the pelvis, alone or as part of a generalised disease, detected by clinical examination, radiology and/or histopathology.

Scheduled follow-up

Cohort A: During the study period, there was no standardised follow-up programme after rectal cancer surgery in the region of Västra Götaland. Patients were followed with CT-scans of the thorax and abdomen at least at one and three years after surgery, which is in line with the Swedish national guidelines as well as the minimum recommendation in the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines [Citation21,Citation24], but some were followed with annual CT-scans for 5 years. Annual visits to an outpatient surgical clinic were customary, and in many cases, rectoscopy was performed on patients with an anastomosis at these clinical examinations. The follow-up for patients with stage IV rectal cancer was individualised.

Cohort B: Follow-up routine varied in the 16 hospitals including patients in the QoLiRECT study but most patients were followed at least at one and three years after surgery with radiology examinations.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarised descriptively with measures of central tendency and variance as appropriate, using SPSS® version 27 for Mac OS.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg, Sweden (Dnr 715-17) and registered at Clinical Trials NCT04406974. The QoLiRECT-study, from which data were retrieved, was approved by the Ethical Review Boards in Sweden (Dnr 595-11) and Denmark (H-3-2012-FSP26).

Results

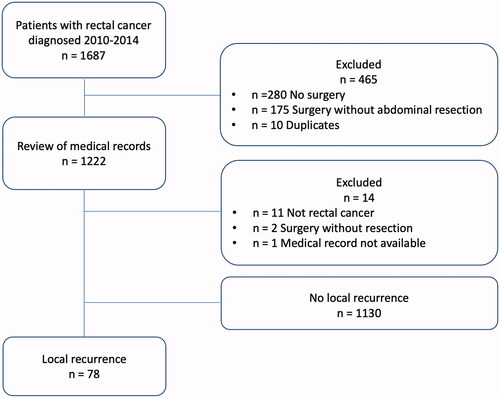

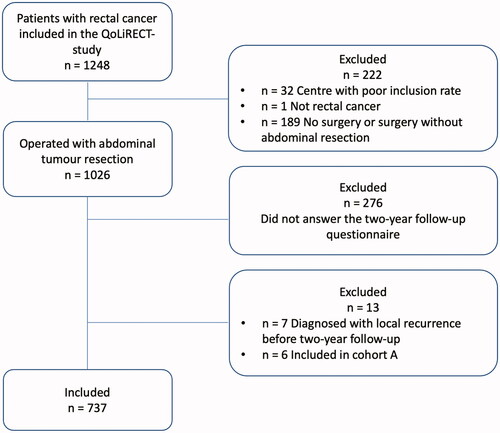

In the retrospective cohort A, a total of 78 out of 1208 patients (6%) were diagnosed with local recurrence during the follow-up period of at least 5 years after primary resection surgery for rectal cancer (). Patient characteristics for cohort A as well as data on primary tumour and treatment are presented in Supplement 1. Cohort B, extracted from the prospective longitudinal observational study QoLiRECT, consisted of 1248 patients, of which 33 patients were subsequently excluded (). Out of the remaining 1215 patients, 1026 patients had undergone abdominal resection surgery, and of these 750 patients answered the questionnaire at two-year follow-up. Of these, 13 patients had a local recurrence diagnosed by the time of the two-year follow-up, or were included in Cohort A with a local recurrence diagnosed at some point, and were thus excluded, resulting in 737 patients without known local recurrence in cohort B. Patient and primary tumour characteristics for cohort B are presented in Supplement 2.

Diagnosing of local recurrence

In the population based retrospective cohort (A), 32 patients were diagnosed with a local recurrence at a scheduled follow-up visit, while 46 patients were diagnosed between such examinations (). The median time from primary surgery to diagnosis of local recurrence was 21 months, ranging from 1 to 99 months (). Eighteen patients were diagnosed more than three years after index surgery. Radiological imaging was the dominating diagnostic modality confirming the diagnosis of local recurrence in 72 out of 78 patients, while clinical examination and/or endoscopy revealed signs of recurrent disease in 37 patients (). Distant metastases were diagnosed in half of the patients before or at the same time as diagnosis of the local recurrence.

Table 1. Diagnosis and management of local recurrence (Cohort A).

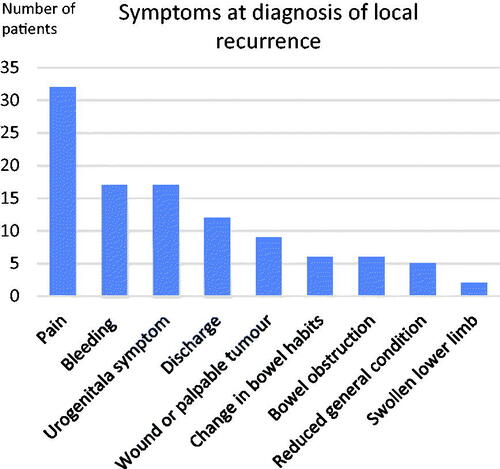

Symptoms at diagnosis of local recurrence

In cohort A, 58 patients had symptoms at the time of diagnosis of local recurrence, and 20 patients were asymptomatic at this point (). Of those diagnosed at scheduled follow-up visits 13 of 32 patients had symptoms, while almost all of those who were diagnosed between follow-up visits, 45 out of 46, were symptomatic, the exception being one patient diagnosed through radiology performed for suspected abdominal wall metastases. The most common symptom was pain (32/78), followed by bleeding and urogenital symptoms (). Of the symptomatic patients, more than half had multiple symptoms. The duration of symptoms was only documented in the medical records for 25 of the 58 symptomatic patients, and most had experienced symptoms for less than three months at diagnosis. In cohort B were no patients had a local recurrence 115/737 (16%) experienced pain in the abdominopelvic area, and 470/737 (64%) had urogenital symptoms. Pain seemed to be more common in patients with local recurrence compared with patients treated for rectal cancer without local recurrence at two-year follow-up.

Management of local recurrence

In cohort A, at the time of diagnosis of local recurrence, 16/78 patients were considered possible to treat with a curative intent, while the remaining 62 patients were treated with palliative intent (). Out of the patients treated with a curative intent 15/16 were discussed at a multidisciplinary team conference (MDT), and the corresponding proportion for patients treated with palliative intent was 39/62. Of the patients treated with curative intent 12/16 received neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with chemo- and/or radiotherapy for the local recurrence. A resection of the tumour was possible in 13/16 patients, and a microscopically radical resection was achieved in 7/13. Of the patients treated with palliative intent a majority were treated with surgery and/or chemo-and/or radiotherapy, while 16/62 patients were given symptom-directed palliative care ().

Outcome after local recurrence

In cohort A, the median survival after the diagnosis of local recurrence was 37 months for patients treated with curative intent (range 9-105) and 10 months for patients treated with a palliative intent (range 0–65) (). At the end of follow-up, 9/16 patients treated with curative intent were still alive, and six of those were considered tumour free. The corresponding number for patients treated with a palliative intent was 6/55 still alive, and two patients were considered tumour free although initially not considered possible to cure.

Table 2. Outcome (Cohort A).

Discussion

In this retrospective population-based study of patients with local recurrence of rectal cancer, most were not diagnosed in a scheduled follow-up programme, but were diagnosed with symptomatic disease between scheduled follow-up visits. Most patients had symptoms at diagnosis but only pain was identified as a possible alarm symptom.

Our findings about symptoms may reflect that patients do not know which symptoms should prompt them to contact their surgical team to discuss an additional check-up. However, since symptoms were also common among patients treated for rectal cancer without local recurrence, this is not surprising. Information to patients should perhaps include advice to contact health care if new symptoms occur between follow-up visits, as it is possible that the scheduled follow-up programmes may give some patients a false sense of security with trust in a negative check and in turn lower inclination to seek medical attention when symptoms occur.

Our results are corroborated by previous studies that also have indicated that patients often are symptomatic when diagnosed with local recurrence of rectal cancer [Citation2,Citation33]. One possibility to achieve earlier detection could thus be to educate patients about which symptoms that indicate the need for an extra examination. However, the data from patients without local recurrence (cohort B) suggested that symptoms were common also in patients who had undergone resection surgery for rectal cancer in general, and we found no symptom that exclusively indicated local recurrence. However, while urogenital symptoms affected a large proportion of patients with or without local recurrence, abdominopelvic pain, which was the most common symptom in patients with local recurrence in this as in previous studies [Citation2,Citation33], could be a possible alarm symptom, as it was less common among patients without local recurrence. Prospective studies are required to determine the significance of the individual symptoms for differentiation between patients with higher risk of local recurrence needing an additional examination, and patients who can continue scheduled follow-up. As local recurrence of rectal cancer fortunately is uncommon, a prospective study of this kind would need to be rather large to include a sufficient number of patients with local recurrence to allow such a comparison. It is however possible that self-assessed reporting of symptoms could contribute to earlier diagnosis of recurrent disease if implemented as part of the follow-up, as suggested in a study on lung cancer [Citation34].

The presence of symptoms at diagnosis of local recurrence has previously been reported to be associated to palliative treatment intent [Citation33], which could indirectly suggest that it might be of value to try to identify local recurrence before symptoms develop. Since the scheduled follow-up programme in a majority of cases failed to detect local recurrence at an early asymptomatic stage, a more intensive surveillance may be required to achieve earlier detection. However, while a more intense follow-up programme has been reported to increase the proportion undergoing surgery with curative intent [Citation7–10], it has not been translated into improved long-term survival [Citation7,Citation9–11]. Thus, it is unclear if the increased resource consumption as well as the worry and anxiety that can be associated to more intensive follow-up [Citation35,Citation36] would be balanced by improved survival. Since local recurrence is rare, the majority of patients operated for rectal cancer would not benefit from intensified surveillance in this regard. This underpins the need to identify symptoms or other risk factors, such as stage of the disease [Citation37], to select patients for intensified follow-up. Taking in to account a combination of risk factors, including alarm symptoms, in a predication model for local recurrence [Citation38], it might be possible to tailor the follow-up according to the risk profile of the individual patient.

In the current study, only a minority of patients with local recurrence were treated with curative intent, and even fewer had a microscopically radical resection with a possibility of cure. As expected, survival seemed better for patients treated with curative intent, which suggests that detecting local recurrence at an earlier, resectable stage could be beneficial. It must however be considered that if the prognosis is not improved, diagnosing local recurrences earlier would merely expose the patients to a longer period of living with the knowledge of recurrent disease without possible cure and without any additional benefit. Thus, it is important to take in to account the possibility of lead time bias when studying the effect of earlier detection of local recurrence on survival.

Multidisciplinary team conferences, MDT, have been proposed to affect the treatment given for as well as the outcome of locally advanced rectal cancer [Citation39]. Since local recurrence of rectal cancer is rare, it is reasonable to believe that the experience of each surgeon is limited, which should increase the importance of MDT where the joint experience would be larger. In this study, a larger proportion of patients, who were discussed in an MDT, underwent treatment with curative intent. Not discussing some cases in an MDT may have influenced the treatment given to those patients, though it is possible that they were not deemed available for curative treatment why MDT was not considered necessary. However, what is regarded as curable changes over time, and including palliative cases in a multidisciplinary meeting might increase the number of curatively treated patients as well as adding valuable experience to the individualised care given also to patients with incurable disease, why MDT is always warranted.

The main strengths of this study are the population-based design and the long follow-up (cohort A). The diagnosis of local recurrence was confirmed through review of the medical records for all patients in cohort A who underwent surgery for rectal cancer diagnosed during the study period, to reduce the risk of missing cases. The comparative material from QoLiRECT (cohort B) has strengths including the prospective design, and the international and multicentre set-up with 16 centres including patients from county, regional and university hospitals. A further strength in cohort B is that symptoms and functional disorders were reported directly by the patients through the use of specific questionnaires returned to a third party. In contrast a limitation in cohort A is the retrospective study design, and the use of the medical records written by healthcare professionals as the source of information on symptoms which may result in an underreporting. Thus, there are limitations when comparing these two cohorts as the different sources of data could mean that symptoms are reported to different extents. Further, data on all symptoms of interest were not available for cohort B, for example bleeding which was one of the most common symptoms in patients with local recurrence. As data for cohort B were based on the two-year questionnaire, a not insignificant proportion of the original QoLiRECT-cohort was excluded as they did not answer the questionnaire, which is a possible source of bias. Moreover, the frequency of local recurrence in cohort B at two years was low, probably due to some patients with early local recurrence being deceased at the time of the two-year questionnaire, and some patients not having gone through their planned two-year check-up when answering the questionnaire. The scheduled follow-up differed somewhat between hospitals in both cohorts; however, the aim was not to evaluate a particular follow-up program.

In conclusion, pain reported by patients after rectal cancer surgery could be an alarm symptom for local recurrence. Since the majority of the patients were symptomatic at diagnosis of local recurrence, one possibility could be to enable patients to contact health care if certain symptoms occur. However carefully designed prospective studies are needed to determine if there are more specific alarm symptoms indicating local recurrence that could be used to differentiate these patients from those without local recurrence.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg, Sweden (Dnr 715-17 and Dnr 595-11) and Denmark (H-3-2012-FSP26). The study was registered at Clinical Trials NCT04406974 and NCT01477229.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study can be shared upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author (SW).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJ. The impact of recurrent rectal cancer on quality of life. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001; 27(4):349–353.

- Kodeda K, Derwinger K, Gustavsson B, et al. Local recurrence of rectal cancer: a population-based cohort study of diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(5):e230-7–e237.

- Denost Q, Faucheron JL, Lefevre JH, et al. French current management and oncological results of locally recurrent rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(12):1645–1652.

- Hagemans JAW, van Rees JM, Alberda WJ, et al. Locally recurrent rectal cancer; long-term outcome of curative surgical and non-surgical treatment of 447 consecutive patients in a tertiary referral centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(3):448–454.

- Jankowski M, Las-Jankowska M, Rutkowski A, et al. Clinical reality and treatment for local recurrence of rectal cancer: a single-center retrospective study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(3):286.

- Matsuyama T, Yamauchi S, Masuda T, Japanese Study Group for Postoperative Follow-up of Colorectal Cancer, et al. Treatment and subsequent prognosis in locally recurrent rectal cancer: a multicenter retrospective study of 498 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(6):1243–1250.

- Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9(9):Cd002200.

- Verberne CJ, Zhan Z, van den Heuvel E, et al. Intensified follow-up in colorectal cancer patients using frequent Carcino-Embryonic antigen (CEA) measurements and CEA-triggered imaging: results of the randomized "CEAwatch" trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(9):1188–1196.

- Pita-Fernández S, Alhayek-Aí M, González-Martín C, et al. Intensive follow-up strategies improve outcomes in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer patients after curative surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):644–656.

- Primrose JN, Perera R, Gray A, FACS Trial Investigators, et al. Effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer: the FACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(3):263–270.

- Wille-Jørgensen P, Syk I, Smedh K, COLOFOL Study Group, et al. Effect of more vs less frequent follow-up testing on overall and colorectal cancer-specific mortality in patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer: the COLOFOL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 19(20):2095–2103.

- Rosati G, Ambrosini G, Barni S, GILDA working group, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus minimal surveillance of patients with resected dukes B2-C colorectal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):274–280.

- Maurer CA, Renzulli P, Kull C, et al. The impact of the introduction of total mesorectal excision on local recurrence rate and survival in rectal cancer: long-term results. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(7):1899–1906.

- den Dulk M, Krijnen P, Marijnen CA, et al. Improved overall survival for patients with rectal cancer since 1990: the effects of TME surgery and pre-operative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(12):1710–1716.

- Bernardshaw SV, Ovrebo K, Eide GE, et al. Treatment of rectal cancer: reduction of local recurrence after the introduction of TME - experience from one university hospital. Dig Surg. 2006;23(1-2):51–59.

- Folkesson J, Birgisson H, Pahlman L, et al. Swedish rectal cancer trial: long lasting benefits from radiotherapy on survival and local recurrence rate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5644–5650.

- van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):575–582.

- Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry. Rectal Cancer 2019 - National quality report for the year 2019 from the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry. [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Dec 12]. Avaliabel from: https://www.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/tjock–och-andtarm-anal/kvalitetsregister/tjock–och-andtarm-2020/rektalrapport-2019.pdf.

- Kodeda K, Johansson R, Zar N, et al. Time trends, improvements and national auditing of rectal cancer management over an 18-year period. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(9):O168–79.

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89–103.

- Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, ESMO Guidelines Committee, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_4):iv22–iv40.

- Martin LA, Gross ME, Mone MC, et al. Routine endoscopic surveillance for local recurrence of rectal cancer is futile. Am J Surg. 2015;210(6):996–1001. discussion 1001–2.

- Tronstad PK, Simpson LVH, Olsen B, et al. Low rate of local recurrence detection by rectoscopy in follow-up of rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(3):254–260.

- Regional Cancer Centers in Collaboration. Swedish National Care Program for ColoRectal Cancer. 2021.

- Sørensen CG, Karlsson WK, Pommergaard HC, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of carcinoembryonic antigen to detect colorectal cancer recurrence - A systematic review. Int J Surg. 2016;25:134–144.

- Nicholson BD, Shinkins B, Pathiraja I, et al. Blood CEA levels for detecting recurrent colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):CD011134.

- Mathai RA, Vidya RVS, Reddy BS, et al. Potential utility of liquid biopsy as a diagnostic and prognostic tool for the assessment of solid tumors: implications in the precision oncology. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):373.

- Diehl F, Li M, Dressman D, et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(45):16368–16373.

- Registry SCC. Rectal Cancer 2018 - National Quality Report for the year 2018 [Internet]2018.

- Asplund D, Heath J, González E, et al. Self-reported quality of life and functional outcome in patients with rectal cancer–QoLiRECT. Dan Med J. 2014 May;61(5):A4841.

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23(2):129–138.

- Westberg K, Palmer G, Johansson H, et al. Time to local recurrence as a prognostic factor in patients with rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(5):659–666.

- Westberg K, Palmer G, Hjern F, et al. Population-based study of factors predicting treatment intention in patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104(13):1866–1873.

- Denis F, Yossi S, Septans AL, et al. Improving survival in patients treated for a lung cancer using self-evaluated symptoms reported through a web application. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(5):464–469.

- Lampic C, Wennberg A, Schill JE, et al. Anxiety and cancer-related worry of cancer patients at routine follow-up visits. Acta Oncol. 1994;33(2):119–125.

- Nordin K, Glimelius B, Påhlman L, et al. Anxiety, depression and worry in gastrointestinal cancer patients attending medical follow-up control visits. Acta Oncol. 1996;35(4):411–416.

- Kudose Y, Shida D, Ahiko Y, et al. Evaluation of recurrence risk After curative resection for patients With stage I to III colorectal cancer using the hazard function: Retrospective analysis of a single-institution large cohort. Ann Surg. 2022;275(4):727–734.

- Waldenstedt S, Bock D, Haglind E, et al. Intraoperative adverse events as a risk factor for local recurrence of rectal cancer after resection surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24(4):449–460.

- Palmer G, Martling A, Cedermark B, et al. Preoperative tumour staging with multidisciplinary team assessment improves the outcome in locally advanced primary rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(12):1361–1369.