Abstract

Background

Overall survival (OS) with advanced esophageal or gastric cancer is poor. To avoid overly aggressive treatments at the end-of-life and assure adequate end-of-life quality, the decision to focus on symptom-centered palliative care (PC) and terminate anticancer treatments, i.e., the PC decision, should be made in time.

Material and methods

We reviewed the charts of patients (N = 160) with esophageal or gastric cancer treated at the Department of Oncology at Helsinki University Central Hospital in 2013 and deceased by December 2014. The use of acute services (Emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations) and places of death were compared according to the timing of the PC decision. Reasons for ED visits and hospitalizations were collected.

Results

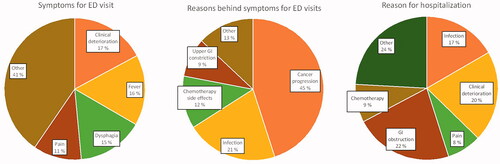

The median OS from diagnosis of advanced cancer was 6 months. Anti-cancer treatments were never started for 34% of the patients. The PC decision was made early (>30 days before death) for 54% of the patients and late (≤30 days before death) or not at all for 46%. Patients with late or no PC decision died more often in tertiary/secondary hospital (29 versus 7%, p = 0.001) and had more ED visits (49 versus 29%, p < 0.001) and hospitalizations (53 versus 28%, p = 0.001) in their last month, and visited the PC unit less often (18 versus 69%, p < 0.001), than the patients with early PC decision. The ED visits were most commonly related to cancer progression, and clinical deterioration (17%), fever (16%), and dysphagia (15%) were the most common symptoms.

Conclusion

The decision to focus on PC and terminate anticancer treatments, i.e., the PC decision, was made late or not at all in every other patient, leading to increased tertiary/secondary hospital service use and deaths at tertiary/secondary hospital. Early decision-making increased end-of-life care at specialized PC services or at home, implying better end-of-life care.

Introduction

The prognosis of esophageal and gastric cancers is poor: 5-year survival rates are 16 and 26%, respectively [Citation1]. The majority (70–80%) of these cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage [Citation2–5], with an overall survival of 8–11 months with life-prolonging chemotherapy and 3–4 months with palliative care (PC) only [Citation6–9]. Patients with advanced esophageal and gastric cancers suffer from major symptom burden and functional deterioration [Citation10–12]. The primary tumor causes upper gastrointestinal obstructions and inadequate nutritional intake, leading to weight loss and cachexia [Citation13]. Fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms, like nausea, further proceed to cachexia and anorexia [Citation14]. Poor physical functioning and malnutrition predict poor prognosis [Citation15–18]. The complication risk increases, and response to anticancer treatments decreases [Citation17,Citation19].

PC is defined as an approach that aims to relief suffering and improve quality of life (QOL) among patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illnesses [Citation20]. Considering the aggressive nature of these cancers and impaired QOL, PC should be integrated in the treatment process early during the disease trajectory. PC is associated with better symptom control and better QOL [Citation21], less aggressive treatments at the end-of-life (EOL) and earlier referral to specialized PC [Citation22]. In contrast, administration of chemotherapy late in life increases admissions to hospital, diminishes the chances of dying at home, and may also be associated with shortened survival time [Citation23]. A high number of Emergency Department (ED) visits or hospitalizations, chemotherapy administration near death, intensive care admission in the last month, no or very late admission to specialized PC, and death in acute care hospital setting indicate poor quality EOL care [Citation24,Citation25].

Despite the advantages of PC, aggressive cancer treatment at the EOL (>10% of patients treated with systemic anticancer treatments 14 days before death) [Citation24] is still common and PC is integrated into cancer care relatively late in life [Citation26,Citation27]. We have previously reported from a heterogeneous cancer population that termination of anticancer treatments and focusing on PC happens approximately 6 weeks before death [Citation28] and 18% of the patients were still receiving systemic anticancer therapy 14 days before death. The terminology and the timing of the PC period are not well established. In earlier studies PC referral is often defined early when done ≥30 [Citation29,Citation30] to >90 days [Citation31,Citation32] before death.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the timing of the PC decision, i.e., the decision to terminate life-prolonging anticancer treatments and focus on PC, of patients with esophageal or gastric cancer and the impact of the PC decision on acute resource use (ED visits and hospitalizations) and the place of death. The secondary aim was to study the reasons for ED visits and hospitalizations at EOL.

Material and methods

Cohort selection

All adults with esophageal or gastric cancer diagnosis (ICD-10 C15–C16) treated at the Department of Oncology, Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH), during 1 January 2013–31 December 2013 and deceased by 31 December 2014, were identified (n = 165) from the HUCH database. The final study group consisted of 160 patients, after five patients were excluded because their primary cause of death was other than esophageal or gastric cancer. Of the patients in the current study, 30 esophageal and 37 gastric cancer patients were also included in our previous study [Citation28,Citation33].

Data sources and collection

We reviewed the medical records of these 160 patients. The information collected from the medical records included age, gender, cancer diagnosis, anticancer treatments, PC decisions, do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, ED visits and hospitalizations, place of death, University hospital PC outpatient unit visits, height, weight before cancer diagnosis and the last recorded weight and nutritional therapist consultations. Symptoms for ED visits, reasons beneath these symptoms and reasons for hospitalizations were also collected. Most of the data was collected in structured form, but some data (e.g., reason for ED visits and hospitalizations) was collected manually from hospital charts. Primary care data (visits, hospitalizations) was not available.

Palliative care decision

The PC decision is defined as termination life-prolonging anticancer treatments and focusing on PC. Patients were divided into two groups based on the timing of the PC decision: (1) no PC decision or PC decision made during the last 30 days before death and (2) PC decision made more than 30 days before death. There is a PC outpatient unit in the Helsinki University Hospital, but municipalities are responsible for EOL care. At the time of our study, 2013–2014, early integrated PC during anticancer treatments was not widely used.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including medians, interquartile ranges, means, ranges, frequencies, and percentages were used for patient characteristics. We compared patient groups based on the timing of the PC decision. Comparisons were made using a one-way ANOVA for continuous variables (e.g., time from diagnosis of advanced cancer to death), and Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square for categorical variables (e.g., whether the patient visited ED in the last month or place of death). If variances in groups were not equal, the analysis was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. The statistical analyses were done by two of the authors (P. K. and R. L).

The completed STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) checklist is provided in Supplementary Material.

Ethical considerations

According to the Finnish regulation for research [Citation34], no ethics committee approval is needed in retrospective register based studies. The authorities of HUCH gave permission for this retrospective registry-based study. All data are stored and handled according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Results

Patient characteristics

In this cohort of 160 adults with esophageal or gastric cancer, approximately half of the patients had esophageal cancer (49%) and half (51%) had gastric cancer. Other characteristics are provided in .

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Of all the patients, 55 patients (34%) were referred directly to PC and were not given any treatment with life-prolonging intent. These patients’ median OS after the diagnosis of advanced cancer was 3 months as compared to eight months in patients who received anticancer treatments with life-prolonging intent (n = 98).

The most commonly used first line chemotherapy regimen for advanced cancer was a combination of epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine (EOX), and for the second line treatment docetaxel. More than half (51%) of the life-prolonging chemotherapies were interrupted because of progressive disease, 24% were terminated because of side-effects, and 5% because of death of the patient, and 20% of the treatments were intentionally paused in partial or stable response.

The median weight loss in the follow-up time was 20% (range − 3.5–50%). The median Body Mass Index (BMI) before cancer diagnosis was 26 (range 16–43) and the last recorded median BMI was 20 (range 13–33).

Palliative care decision

During the follow-up, the PC decision was made for 135 (84%) out of 160 patients. The PC decision was made more than 30 days before death for 87 patients (54%), and 30 days or less before death for 48 patients (30%), and not at all for 25 patients (16%). Compared to patients with no or late PC decision, patients with early PC decisions more often died at home or in a nursing home (23 versus 12%, p = 0.001), visited the PC unit more often (69 versus 18%, p < 0.001), and had fewer ED visits (29 versus 49%, p = 0.0009) and hospitalizations (28 versus 53%, p = 0.001) in their last month. Time from the diagnosis of advanced cancer to death was longer in patients with early PC compared to patients with no or late PC decision (8 versus 4 months, p < 0.001). A comparison of subgroups based on the timing of the PC decision is presented in .

Table 2. Comparison of subgroups based on timing of the palliative care decision.

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations

The total number of ED visits was 413. After the diagnosis of cancer, the mean number of ED visits was 2.6 per person and the median was 2 (range 0–14). From ED, 34% of the patients were discharged home, 61% referred to a tertiary/secondary hospital ward, and 5% to a primary care hospital ward. The total number of hospitalizations was 395. The mean number of hospitalizations per person was 2.5 and the median was 2 (range 0–14). Symptoms for ED visits, reasons behind these symptoms, and reasons for hospitalizations are shown in .

Figure 1. Symptoms for emergency department (ED) visits, reasons behind symptoms and reasons for hospitalizations. Upper GI constriction – no evidence of cancer progression, e.g., stricture. Chemotherapy side effects excluding chemotherapy-induced infection, infection including chemotherapy-induced infection.

The last 30 days of life

Fourteen patients (9%) received chemotherapy within 14 days before death and 23 patients (14%) within 30 days before death. Eight patients received radiation therapy in the last 30 days before death.

In the last 30 days of life, the most common symptoms for ED visits were clinical deterioration and dysphagia (21 and 19%, respectively), and the most common reason behind the symptoms (77%) was cancer progression. From the ED, 63 patients (68%) were admitted to tertiary/secondary hospital. Of the patients admitted to hospital (n = 85) during the last month of life, 35 patients (40%) were discharged home from hospital, 21 patients (25%) died during hospitalization, 10 patients (12%) were discharged to hospice/specialized PC wards, and 20 patients (24%) to primary care hospital.

Discussion

The prognosis of esophageal and gastric cancer is very poor. In our study, no systemic anticancer treatment was even started in every third patient. Of those patients who started systemic therapy, every fourth patient interrupted the therapy because of the side effects. The decision to terminate anticancer treatments i.e., PC decision, was made late or not at all in every other patient, increasing the use of tertiary/secondary hospital services (ED visits and hospitalizations) in the last month of life and the risk of dying in tertiary/secondary hospital.

The late decision making and the lack of advanced care planning led to increased use of tertiary/secondary hospital services at the EOL. Every other patient with no or late PC decisions visited ED and was hospitalized in tertiary/secondary hospital during the last month of life, compared to less than one-third of patients with early PC decisions. In a previous study of patients with GI cancer, 19% of hospitalizations occurring near the EOL were identified as potentially avoidable [Citation35]. In that study, the most common reasons for hospital admission were fever/infection, abdominal pain, and GI tract obstruction, while in our study the most common reasons for hospitalizations were GI tract obstruction, clinical deterioration, and infections. Cancer progression explained most of the ED visits, which could at least partly reflect a lack of advanced care planning and early integrated PC. ED visits led to hospitalization in two-thirds of patients and one fourth of them died during hospitalization, suggesting that ED visits increase the risk of dying in tertiary/secondary hospital and not being admitted to specialized EOL care. Instead, if the PC decisions had been made earlier, more patients would have visited the PC unit and the probability of being referred to specialized PC would have increased, which are considered signs of better EOL quality [Citation24,Citation25].

In the present study, patients with early PC decision had better OS than patients with aggressive cancer treatments at the EOL. This could, however, be related to patient selection rather than timing of PC decision because of the unrandomized nature of the population. Patients with aggressive disease could have had rapid progression and shorter life expectancy after termination of the anti-cancer treatments. However, this further highlights the need for integration of PC into oncology at an early stage of the disease.

Our cohort is assumed to represent the general esophageal and gastric cancer population. In line with the previous literature, median overall survival with advanced disease was 6 months [Citation6–9]. In addition, EOX and docetaxel were the most frequently used chemotherapy regimens for advanced disease, which are in accordance with current guidelines [Citation36,Citation37].

Thirty-four percent of the patients did not receive any anti-cancer treatment for advanced cancer, and their median overall survival (mOS) was particularly poor, only three months as compared to eight months for patients who received life-prolonging chemotherapy. Likewise, in a previous retrospective study [Citation38] with advanced gastro esophageal adenocarcinomas, 49% of patients received no oncological treatment, with mOS of 3 compared to 9 months with life-prolonging chemotherapy. In our study, half (51%) of the life-prolonging chemotherapies were eventually terminated because of progression, 24% because of side-effects, and 5% because of the death of the patient.

In the present study, cancer treatment at the EOL was not overly aggressive, as less than 10% of patients received chemotherapy 14 days prior to death, which is a commonly accepted figure [Citation24]. The median time from last chemotherapy to death was 69 days, even though the PC decision was made late (within 30 days prior death) or not at all for 46% of the patients. This discrepancy implies a lack of timely advanced care planning for EOL care.

Significant weight loss was very common in our cohort. Almost half of our patients lost ≥20% of their bodyweight during the follow-up period. This was true despite their access to nutritional therapy. In line with a previous study, most (60%) of the patients with esophageal or gastric cancer were malnourished [Citation39]. In another study, gastrointestinal cancer patients with weight loss were found to have shorter overall survival and decreased QOL and performance status [Citation18].

The major strength of our study is its population-based real-life data representing all the deceased esophageal and gastric cancer patients in our hospital area during the study period. However, there are some limitations in this study, including its retrospective design and small cohort size. Due to the retrospective design of the study, QOL data was not available. The lack of medical records in primary health care services is an additional limitation, since this information is not available in our hospital databases. The final limitation is the age of data, considering the progress in the field of palliative care in the last years, as the value of early integrated PC has been documented [Citation40]. However, early integrated PC is still not widely available [Citation41], but the traditional PC starting after termination of anticancer therapy is still often used, leading us to believe that our findings are relevant also in current circumstances, showing that even small-scale palliative care does have impact.

Conclusions

OS of advanced esophageal or gastric carcinoma is poor. Every third patient was not even a candidate for anti-cancer treatment. The PC decision was made late or not at all in every second patient even though anti-cancer treatments were terminated, leading to increased tertiary/secondary hospital service use and deaths at tertiary/secondary hospital. Early decision-making and advanced care planning enable early access to EOL care at specialized PC services or at home, signaling better EOL care.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.5 KB)Acknowledgments

Kenneth Quek is acknowledged for language revision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Finnish Cancer Registry [Internet]. Finland; 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 27]. Available from: http://cancerregistry.fi/

- Castro C, Boseti C, Malvezzi M, et al. Patterns and trends in esophageal cancer mortality and incidence in Europe (1980–2011) and predictions to 2015. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):283–290.

- Rouvelas I, Zeng W, Lindblad M, et al. Survival after surgery for oesophageal cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(11):864–870.

- Janunger KG, Hafström L, Nygren P, SBU-Group, Swedish Council of Technology Assessment in Health Care, et al. A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in gastric cancer. Acta Oncol. 2001;40(2–3):309–326.

- Coupland VH, Lagergren J, Lüchtenborg M, et al. Hospital volume, proportion resected and mortality from oesophageal and gastric cancer: a population-based study in England, 2004–2008. Gut. 2013;62(7):961–966.

- Murad AM, Santiago FF, Petroianu A, et al. Modified therapy with 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer. 1993;72(1):37–41.

- Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(2):163–168.

- Jung H-K, Tae CH, Lee H-A, Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research, et al. Treatment pattern and overall survival in esophageal cancer during a 13-year period: a nationwide cohort study of 6,354 Korean patients. PLOS One. 2020;15(4):e0231456.

- Pyrhönen S, Kuitunen T, Nyandoto P, et al. Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(3):587–591.

- Chau I, Fuchs CS, Ohtsu A, et al. Association of quality of life with disease characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with advanced gastric cancer: exploratory analysis of RAINBOW and REGARD phase III trials. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:115–123.

- Blazeby JM, Farndon JR, Donovan J, et al. A prospective longitudinal study examining the quality of life of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88(8):1781–1787.

- O'Neill L, Moran J, Guinan EM, et al. Physical decline and its implications in the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):601–618.

- Kern K, Norton J. Cancer cachexia. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12(3):286–298.

- Anandavadivelan P, Lagergren P. Cachexia in patients with oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(3):185–198.

- Jack S, West MA, Raw D, et al. The effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness and survival in patients undergoing oesophagogastric cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(10):1313–1320.

- Nikniaz Z, Somi MH, Naghashi S. Malnutrition and weight loss as prognostic factors in the survival of patients with gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74:1–6.

- Grundmann O, Yoon SL, Williams JJ. Cachexia in patients with gastrointestinal cancers: contributing factors, prevention, and current management approaches. EMJ Gastroenterol. 2020;9(1):62–70.

- Andreyev HJN, Norman AR, Oates J, et al. Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(4):503–509.

- Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(4):491–497.

- World Health Organization. Palliative care, vol. 2021; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care.

- Merchant SJ, Brogly SB, Booth CM, et al. Palliative care and symptom burden in the last year of life: a population-based study of patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(8):2336–2345.

- Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120(11):1743–1749.

- Näppä U, Lindqvist O, Rasmussen BH, et al. Palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life. Ann Oncol off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2011;22(11):2375–2380.

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(6):505–509.

- Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1133–1138.

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315–321.

- Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1587–1591.

- Hirvonen OM, Leskelä R-L, Grönholm L, et al. Assessing the utilization of the decision to implement a palliative goal for the treatment of cancer patients during the last year of life at Helsinki University Hospital: a historic cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(12):1699–1705.

- Poulose JV, Do YK, Neo PSH. Association between referral-to-death interval and location of death of patients referred to a hospital-based specialist palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(2):173–181.

- Blackhall LJ, Read P, Stukenborg G, et al. CARE track for advanced cancer: impact and timing of an outpatient palliative care clinic. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):57–63.

- Alsirafy SA, Raheem AA, Al-Zahrani AS, et al. Emergency department visits at the end of life of patients with terminal cancer: pattern, causes, and avoidability. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(7):658–662.

- Nieder C, Tollåli T, Haukland E, et al. Impact of early palliative interventions on the outcomes of care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(10):4385–4391.

- Hirvonen OM, Leskelä R-L, Grönholm L, et al. The impact of the duration of the palliative care period on cancer patients with regard to the use of hospital services and the place of death: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):37.

- Guidelines for ethical review in human sciences. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 8]. Available from: https://tenk.fi/en/advice-and-materials/guidelines-ethical-review-human-sciences.

- Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):496–503.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Gastric cancer 2.2021 [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers 2.2021 [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/esophageal.pdf.

- Cavanagh KE, Baxter MA, Petty RD. Best supportive care and prognosis: advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021. DOI:10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002637

- Hébuterne X, Lemarié E, Michallet M, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition and current use of nutrition support in patients with cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(2):196–204.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742.

- Collins A, Sundararajan V, Burchell J, et al. Transition points for the routine integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(2):185–194.