Abstract

Background

Oesophageal cancer surgery is extensive with high risk of long-term health-related quality of life (HRQL) reductions. After hospital discharge, the family members often carry great responsibility for the rehabilitation of the patient, which may negatively influence their wellbeing. The purpose was to clarify whether a higher caregiver burden was associated with psychological problems and reduced HRQL for family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors.

Material and methods

This was a nationwide prospective cohort study enrolling family members of all patients who underwent surgical resection for oesophageal cancer in Sweden between 2013 and 2020. The family caregivers reported caregiver burden, symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and HRQL 1 year after the patient’s surgery. Associations were analysed with multivariable logistic regression and presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences between groups were presented as mean score differences (MSD).

Results

Among 319 family caregivers, 101 (32%) reported a high to moderate caregiver burden. Younger family caregivers were more likely to experience a higher caregiver burden. High-moderate caregiver burden was associated with an increased risk of symptoms of anxiety (OR 5.53, 95%CI: 3.18–9.62), depression (OR 8.56, 95%CI: 3.80–19.29), and/or posttraumatic stress (OR 5.39, 95%CI: 3.17–9.17). A high-moderate caregiver burden was also associated with reduced HRQL, especially for social function (MSD 23.0, 95% CI: 18.5 to 27.6) and role emotional (MSD 27.8, 95%CI: 19.9 to 35.7).

Conclusions

The study indicates that a high caregiver burden is associated with worse health effects for the family caregiver of oesophageal cancer survivors.

Background

After hospital discharge, family members of cancer survivors often carry great responsibility for the continued care and rehabilitation of the patient. A family member, partner or friend providing a broad range of care for the cancer survivor is generally regarded as an informal or family caregiver [Citation1]. Their role is complex and may involve a range of activities from assisting in household activities, mobility, health, and medical care such as managing treatment-related effects, to providing emotional support, and coping with the uncertainty of the cancer trajectory [Citation2]. In previous literature, it has been described that family caregivers of cancer patients experience significant caregiver burden, a high prevalence of psychological distress and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQL) [Citation3–5] and there seems to be a correlation between patients’ and their caregivers’ level of distress (dyadic coping) [Citation6,Citation7]. Suffering from psychological distress, while also caring for a person newly diagnosed with cancer who additionally has undergone extensive surgery, may hamper the family caregiver’s capability to work, imposing financial and emotional burden. Deterioration in the health of the family caregiver may also limit his/her ability to contribute with help in the patient’s recovery. Caregiver burden is a multidimensional term and involves problems in shouldering the responsibility as a caregiver. When care demands exceed resources, caregiving may have negative health consequences [Citation8]. Even though the prevalence of unmet needs is reduced with time, a significant minority of caregivers continues to experience needs related to the cancer experience during the survivorship phase [Citation9]. To date, there is a paucity of information on burdens associated with the patients’ specific cancer diagnosis. One understudied population is family caregivers of surgical cancer patients [Citation10]. Oesophageal cancer is a severe disease with poor prognosis [Citation11]. About 30% of diagnosed patients are eligible for curative intended treatment and of those who undergo this treatment, the 5-year survival rate is about 30%. The prevailing curative treatment of oesophageal cancer is neoadjuvant therapy followed by oesophagectomy, which is an extremely extensive surgery where the oesophagus is removed and replaced by the upper part of the stomach [Citation11]. Following the treatment, life-long reductions of HRQL are common [Citation12–15] and approximately one-third of the patients suffer from symptoms of anxiety and/or depression [Citation16]. Most postoperative symptoms are related to the digestive tract, e.g., eating difficulties, dysphagia, dumping and severe reflux [Citation12–Citation15] and may be explained by the permanent anatomical changes following oesophagectomy, such as the loss of the gastric reservoir, potential scarring of the proximal oesophagus, the removed antireflux barrier of the gastric cardia and vagotomy [Citation15]. To adapt to the consequences of the cancer disease and its treatments, complex life-changes are often required which also present challenges for the close family. Since the majority of oesophageal cancer patients are elderly (>60 years) men when they receive the cancer diagnosis [Citation11], a family member usually becomes the primary caregiver. In a recent qualitative study, family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors reported experiencing extensive life-changes after the patients’ surgery. They stated that problems with food intake and a general weakened condition of the patient led to fewer social interactions for the patient but also contributed to feelings of own isolation [Citation17]. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has investigated caregiver burden among family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors. In this study, one third of the spouses reported high to moderate caregiver burden 3 years after treatment and higher burden were associated with depressive symptoms among the caregivers [Citation18]. However, only 47 couples (patient and family caregivers) were included in the single centre study and larger studies were recommended to confirm the results. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide, prospective study to elucidate whether a high caregiver burden among family caregivers of survivors of oesophageal cancer was associated with psychological distress and reduced HRQL.

Material and methods

Study design

All patients who underwent surgery for oesophageal cancer in Sweden between January 2013 and June 2020 were eligible for inclusion in the prospective nationwide study entitled ′Oesophageal Surgery on Cancer patients – Adaption and Recovery study (OSCAR)’. One year after surgery, consenting Swedish-speaking patients with no cognitive impairments were included in the study. The patients, in turn, selected which family caregiver to include, on the conditions that the family caregiver was a Swedish speaking adult and conformed with the Family Caregiver Alliance’s definition of an informal caregiver: An informal caregiver is an unpaid individual (e.g., a spouse, partner, family member, friend or neighbor) involved in assisting with activities in daily living and/or medical tasks [Citation19]. For the study, it was not required that the family caregiver cohabited with the person with cancer who needed care. The research project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (diary number 2013/844-31/1). All participants gave written informed consent.

Data collection

Detailed description of the OSCAR data collection can be found elsewhere [Citation20]. In brief, the patient and his/her closest family caregiver were followed up with a questionnaire kit containing well-validated instruments assessing the psychological status and HRQL aspects in the first years after the patient’s surgery. During the 1-year follow-up, a research nurse visited the patient and the family caregiver to obtain the consent form and questionnaire kits. The patient performed an additional web-based questionnaire guided by the research nurse. For the purpose of this study, 1-year postoperative data from the family caregiver were studied. Demographic data on the family caregiver were self-reported and collected in the questionnaire kit.

Exposure

The exposure was caregiver burden assessed with The Caregiver burden scale [Citation21] assessed 1 year after the patient’s oesophagectomy. The self-assessed instrument was developed in Sweden and contains 22-items distributed on a five-factor scale: general strain (8 items), isolation (3 items), disappointment (5 items), emotional involvement (3 items), and environment (3 items). Each item has four response alternatives which generates an overall score between 1 and 4; Not at all (1), Seldom (2), Sometimes (3), and Often (4). Higher scores indicate a higher burden [Citation21]. Results are presented as mean values for the total score and each dimension. Mean scores of 1.00 to 1.99 is considered as a low burden, while 2.00–2.99 corresponds to moderate burden and 3.00–3.99 to high burden. For this study, a total/overall mean score with a cut-off of ≥2 was considered as high to moderate caregiver burden. The scale has been tested for validity and reliability among a Swedish population of caregivers of patients with cognitive disorders [Citation21]. It has also been shown to apply to caregivers of patients with other diagnoses [Citation22]. The reliability was considered as substantial with kappa values above 0.69 [Citation21].

Outcomes

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) assesses anxiety and depression in two separate subscales [Citation23]. The questionnaire contains 14 items and is responded through a four-point scale scored from 0 to 3 [Citation24]. A subscale score ≥8 identifies possible symptoms of anxiety or depression. Internal consistency of HADS has been shown to be satisfactory [Citation25].

Also, the psychometric properties have been validated in a large general population of elderly people in Sweden [Citation26].

Impact of event scale-revised

The instrument Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was used to assess post-traumatic stress symptoms perceived by the family caregivers, in relation to the patient’s cancer diagnosis. The questionnaire contains 22-items and is divided into three subscales; intrusion, avoidance and hyperarousal with five response alternatives graded on a Likert-like scale from 0 to 4 (not at all – extremely). The responses are scored from 0 to 88 where high scores indicate a high symptom burden. A score exceeding 24 is considered as clinically significant symptoms for post-traumatic stress [Citation27].

RAND-36

HRQL was assessed with the RAND-36 Item Health Survey [Citation28,Citation29]. The RAND-36 is identical to the Short Form-36 Item Survey (SF-36) [Citation30] of which items were originally collected from the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) [Citation28]. The RAND-36 is a generic HRQL instrument and contains eight subscales: physical function, physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health, energy/fatigue, social functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. The item responses are scored from 0 to 100. A higher score indicates a better HRQL [Citation28]. The RAND-36 has been validated across the general population in Sweden [Citation31].

Statistical analysis

Missing items in the questionnaires were handled with imputation of mean values (21 patients had one missing question and 9 had 2–7 missing questions). If more than half of the items were missing in the questionnaire, it was excluded from the analysis [Citation32]. Five questionnaires were excluded for Caregiver burden, 2 for HADS and 3 for IES. Characteristics were presented in numbers (n) and proportions (%). Potential differences between groups were compared with student’s t-test and Chi-2 test where appropriate. For associations between caregiver burden and psychological symptoms, multivariable logistic regression was used, and results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For HRQL data, associations were calculated with Chi- Square test for nominal data and t-test for continuous data and presented as mean scores (MS) and mean score differences (MSD) with 95% CI. All data management and statistical analyses were conducted by a senior biostatistician (Asif Johar) with expertise in analyses of patient-reported outcome measures. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics

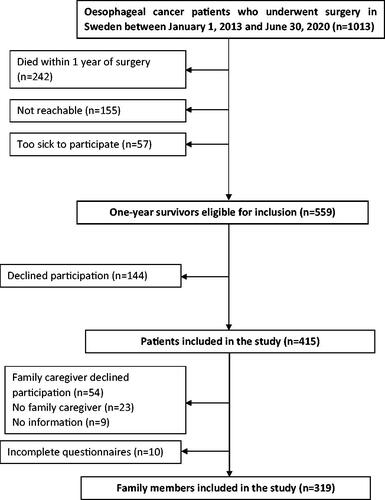

Between January 2013 and June 2020, 1013 patients underwent surgery for oesophageal cancer in Sweden. Among them, 771 survived for at least 1 year and 415 patients were included in the study. Of these, 86 had no family caregiver or had a family caregiver who declined participation. In total, 319 family caregivers with complete data participated in the study (). The mean age of the patients was 67 years. The majority were men (87%) with adenocarcinoma (85%). Approximately 35% had tumour stages III–IV. Among the family caregivers, the majority were spouses (83%), 86% were women and the mean age was 66 years ().

Table 1. Characteristics of family caregivers of patients with oesophageal cancer with low high-moderate caregiver burden.

Family caregiver burden

Among the 319 family caregivers, 101 (32%) reported a high to moderate caregiver burden 1 year after the patient’s surgery. The total mean scores for low versus high caregiver burden were 1.4 and 2.4, respectively. Isolation was the most common aspect of caregiver burden, reported by 143 (45%) of the family caregivers, followed by general strain (n = 124, 39%) and disappointment (n = 122, 38%; ). Family caregivers reporting high to moderate caregiver burden were of younger age compared to those who reported low caregiver burden (p < .05).

Table 2. Caregiver burden scores in family caregivers of patients 1 year after oesophageal cancer surgery presented as numbers and proportions.

Caregiver burden, symptoms of psychological distress, and HRQL

Among the 319 family caregivers, 80 (20%) suffered from symptoms of anxiety, 36 (11%) from depression, and 100 caregivers (32%) suffered from post-traumatic stress. High-moderate caregiver burden was associated with an increased risk of symptoms of anxiety (OR 5.53, 95%CI: 3.18–9.62), depression (OR 8.56, 95%CI: 3.80–19.29), and/or post-traumatic stress (OR 5.39, 95%CI: 3.17–9.17; ). Compared with low caregiver burden, high to moderate burden was associated with reductions in all HRQL aspects (). Specifically, distinct reductions were seen for role physical (MSD 20.8, 95%CI: 12.4–29.3), vitality (MSD 20.3, 05%CI: 15.9–24.8), social function (MSD 23.0, 95% CI: 18.5–27.6), and role emotional (MSD 27.8, 95%CI: 19.9–35.7).

Table 3. Associations between caregiver burden and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress in family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors, presented as numbers (%), odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Table 4. Caregiver burden and HRQL (RAND-36) in family caregivers to oesophageal cancer of oesophageal cancer survivors, presented as mean scores (MS) and mean score differences (MSD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study indicates that a substantial proportion of family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors perceive a high caregiver burden 1 year after surgery and that a higher caregiver burden is associated with psychological problems and reduced HRQL. Our findings indicate potential value to target not only the patient but also the family caregiver for follow-up after oesophageal cancer surgery.

The prospective and population-based design with a relatively high participation rate counteracts selection bias. However, even though the participation rate was acceptable, we cannot rule out that non-participation influenced the results because responders tend to be physically and psychologically healthier. Also, the patients selected their family members for the study which could have possibly introduced selection bias in the study. The use of well-validated questionnaires limited the risk of misclassification. However, HADS was originally developed for hospitalised patients to differentiate the physical symptoms from the psychological effects of the illness [Citation23] and may, therefore, not be optimal for assessing anxiety and depression in caregivers. More recently though, HADS’ psychometric properties have also been evaluated in family caregivers [Citation33]. The paucity of information on psychological status at baseline prevents more extensive adjustments for potential differences between the groups. Inclusion of more detailed baseline characteristics of the family caregivers would have been useful to compare the applicability of results with those of other studies. Finally, the observational design of the study by nature precludes determining causal inference.

A substantial proportion of people are providing unpaid care for an adult with functional or health limitations around the world [Citation19,Citation34]. Still, caregiver burden is often an ignored problem. In the present study, 32% of the family caregivers experienced high to moderate caregiver burden, a result comparable to the prevalence reported in the smaller Dutch study, in which 34% experienced a substantial burden [Citation18]. Slightly more family caregivers suffered from psychological problems in the Dutch study, compared to what was reported in our study. However, this discrepancy might be related to differences in power and/or follow-up time (1 year versus 3 years). Increased caregiver burden has in other previous studies been associated with depressive symptoms [Citation35]. The prevalence of anxiety and post-traumatic stress was substantially higher in these studies than among family caregivers in a female general population [Citation36], whereas depression was in the range of the total general population [Citation37]. In a meta-analysis of 30 included studies with more than 21,000 family caregivers of patients with cancer, the prevalence of anxiety and depression were 47% and 42%, respectively [Citation35]. Since only 10 of the included studies used HADS for assessing psychological symptoms, we cannot rule out that the lower level of anxiety and depression found in our study population is related to the choice of assessment tool. Another explanation may be that family caregivers of patients who received palliative care were not included in our study. Family caregivers of bereaved family members have previously been shown to suffer from more severe psychological problems compared to those who actively provide care during the illness course [Citation38]. In a qualitative study, family caregivers of patients with oesophageal cancer expressed that they felt burdened with the responsibility of the patients’ care after hospital discharge [Citation17]. Most family caregivers were not prepared to take on caregiving tasks, especially more medically skilled caregiving. Younger family caregivers of elderly cancer patients are usually experiencing a higher caregiver burden [Citation39], which also was confirmed in our study. This finding might be explained by that their activities are more constrained and their financial situation less secure compared to older caregivers [Citation40]. Most patients are routinely followed-up years after oesophageal cancer surgery. However, the health and wellbeing of family caregivers are rarely brought up at these meetings.

Healthcare should play a greater role in assessment and aid with support where necessary.

To improve the readiness and clarify what is expected of the caregivers after the patients are discharged, it would be beneficial for them to have access to evidence-based interventions that can alleviate or prevent adverse psychological effects. Because the caregiver burden is complex by nature, recommended interventions that are found likely to reduce caregiver burden are also multifaceted such as caregiver skill training, couples therapy, decision support, and mindfulness-based stress reduction [Citation41]. Education programs including follow-up meetings after surgery for patients and their caregivers could be one way to make sure that all patients and family caregivers receive valuable information, contacts, and tools to improve survivorship.

The current study contributes to the evidence supporting that a high caregiver burden is associated with worse health effects for the family caregiver of oesophageal cancer survivors. This finding is confirmed in studies of other cancer populations and must be addressed in clinical practice. Today, treatments for cancer are complex and since hospital length of stay is getting shorter and nursing home rehabilitation is limited, the number of family caregivers of cancer survivors will increase. Future studies should be focussed on evaluating supportive interventions for patients and their families in the years after cancer treatment.

In conclusion, this nationwide prospective cohort study with follow-up of family caregivers of oesophageal cancer survivors indicates that caregiver burden is a distinct long-term problem with a direct negative effect on the family caregivers’ health and wellbeing.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Anna Schandl, Cecilia Ringborg, and Pernilla Lagergren; Collection and assembly of data: Kalle Mälberg and Pernilla Lagergren; Data analysis: Asif Johar; Interpretation of results and manuscript writing: All authors; Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all participants of the study for sharing their experiences and the members of the Surgical Care Science patient research partnership group for comments throughout the development of the publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request by the corresponding author [AS].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Family Caregiver Alliance. 2022. Definitions; [cited 2022 May 20]. Available from: https://www.caregiver.org/resource/definitions-0/

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995.

- Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):721–732.

- Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2556–2568.

- Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, et al. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1227–1234.

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, et al. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(1):1–30.

- Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):1–12.

- Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(4):438–445.

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Ting A. Family caregivers’ unmet needs in long-term cancer survivorship. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(4):380–383.

- Sun V, Raz DJ, Kim JY. Caring for the informal cancer caregiver. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2019;13(3):238–242.

- Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2383–2396.

- Taioli E, Schwartz RM, Lieberman-Cribbin W, et al. Quality of life after open or minimally invasive esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer-a systematic review. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29(3):377–390.

- Scarpa M, Valente S, Alfieri R, et al. Systematic review of health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(42):4660–4674.

- Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Elbers RG, et al. Meta-analysis shows clinically relevant and long-lasting deterioration in health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(4):1155–1176.

- Schandl A, Lagergren J, Johar A, et al. Health-related quality of life 10 years after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:43–50.

- Hellstadius Y, Lagergren J, Zylstra J, et al. A longitudinal assessment of psychological distress after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(5):746–752.

- Ringborg CH, Schandl A, Wengstrom Y, et al. Experiences of being a family caregiver to a patient treated for oesophageal cancer-1 year after surgery. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):915–921.

- Mohammad NH, Walter AW, van Oijen MGH, et al. Burden of spousal caregivers of stage II and III esophageal cancer survivors 3 years after treatment with curative intent. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(12):3589–3598.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. 2022. Caregiver statistics: demographics; [cited 2022 May 20]. Available from: https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/

- Schandl A, Johar A, Anandavadivelan P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes 1 year after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(6):613–619.

- Elmstahl S, Malmberg B, Annerstedt L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(2):177–182.

- Agren S, Evangelista L, Stromberg A. Do partners of patients with chronic heart failure experience caregiver burden? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(4):254–262.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Altoe G. Defining hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) structure by confirmatory factor analysis: a contribution to validation for oncological settings. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(10):2330–2333.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

- Djukanovic I, Carlsson J, Arestedt K. Is the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) a valid measure in a general population 65–80 years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health Qual Life Out. 2017;15(1):193.

- Weiss DMC. The impact of event scale – revised. New York, Guilford: Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; 1996.

- Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):350–357.

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2(3):217–227.

- Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Ohlsson-Nevo E, Hiyoshi A, Noren P, et al. The Swedish RAND-36: psychometric characteristics and reference data from the Mid-Swed health survey. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):66.

- Bell ML, Fairclough DL, Fiero MH, et al. Handling missing items in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): a simulation study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):479.

- Gough BA, Hudson P. Psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(5):797–806.

- American Association of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute. 2022. Caregiving in the US 2020: American Association of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute. Available from: https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states-01-21.pdf

- Geng HM, Chuang DM, Yang F, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e11863.

- Ditlevsen DN, Elklit A. The combined effect of gender and age on post traumatic stress disorder: do men and women show differences in the lifespan distribution of the disorder? Ann Gen Psychiatr. 2010;9:32.

- Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman A, et al. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ. 2013;1:e98.

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Park ER, et al. Psychological distress in bereaved caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2021;61(3):488–494.

- Ge LX, Mordiffi SZ. Factors associated with higher caregiver burden among family caregivers of elderly cancer patients a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(6):471–478.

- Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative’s cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012;21(3):273–281.

- Jadalla A, Ginex P, Coleman M, et al. Family caregiver strain and burden a systematic review of evidence-based interventions when caring for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020;24(1):31–50.