During the past decade, immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) has become one of the core treatment modalities for several cancer types, such as melanoma, renal cancer, and lung cancer. The majority of immune related adverse events (irAEs) are mild to moderate in severity [Citation1]. Severe irAEs might necessitate discontinuation of ICI, lead to significant morbidity or have a lethal outcome [Citation2]. Cutaneous immune related adverse events (cirAEs) are among the most frequent irAEs [Citation3,Citation4], but treatment related deaths are rare [Citation2]. Among cirAEs, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is the most severe with mortality rates reported to be over 60% [Citation5]. Classic Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and TEN are overlapping reactions characterized by skin and mucous membrane detachment and systemic involvement of various degrees [Citation6]. SJS/TEN is most commonly triggered by medications such as antibiotics, antiepileptic drugs, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but has also been associated with infectious agents, malignancy, and idiopathic causes. The pathogenesis of TEN involves a cell-mediated immune reaction. Destruction of the basal epithelial cells involves accumulation of CD8-positive cells and macrophages in the superficial dermis, potentially resulting in necrosis and detachment of the epidermis [Citation7]. Further, TEN is characterized by Fas- and granulosyn-mediated apoptosis of keratinocytes, initiated by drug-induced cytotoxic T cells. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha and reactive oxygen species are also involved [Citation8]. Somewhat similar to immune therapy related adverse events, TEN has been compared with graft-versus-host disease, in which the T cells (activated or donor) attack the recipient cells that bear a perceived foreign histocompatibility antigen.

In biopsies, early lesions show apoptotic keratinocytes scattered in the basal epidermis, while later lesions show numerous necrotic keratinocytes, full thickness epidermal necrosis and subepidermal bullae. However, clinical correlation is essential to distinguish SJS and TEN, as they may look nearly identical histologically.

Case report

Here, we report two patients, a woman with metastatic melanoma and a man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Both developed TEN during anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 combination therapy. Details on the course, treatment and outcome are shown in . Verbal informed consent for publication was obtained from Patient 1 and from the next of kin of Patient 2.

Table 1. Two patient cases with TEN following ICI.

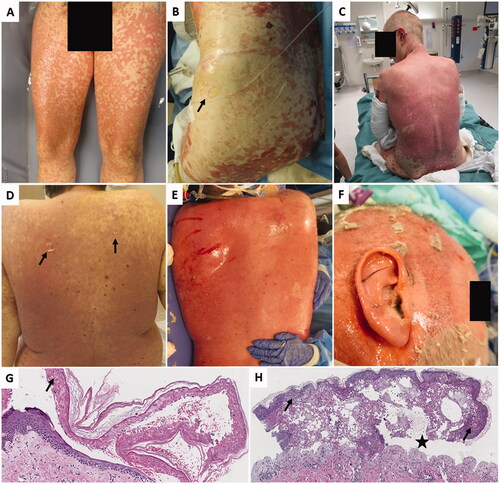

Patient 1, a previously healthy 54-year-old female, started ICI for metastatic melanoma in July 2019. In November 2019, she had an irAE in the form of hypophysitis grade 2 (CTCAE) requiring cortisone replacement therapy and transiently thyroid hormone replacement. In December 2019, she experienced decreased general condition and laboratory testing revealed elevated liver enzymes (ALT 1132 U/L), interpreted as hepatitis grade 4 (CTCAE). She was successfully treated with tapering prednisolone doses from 2 mg/kg, and ICI was paused. From January 2020, she had an evolving maculopapular rash that developed into TEN 16 days later (). TEN was treated with high dose (methyl)prednisolone, cyclosporine and immunoglobulins. ICI was permanently discontinued. She was critically ill before re-epithelialization, but is now fully recovered.

Figure 1. Two patient cases with TEN following ICI. (A) Pt. 1 at day 1 after admission to the BU. (B) Pt. 1 at day 10. (C) Pt. 1 at day 18. (D) Pt. 2 before admission to the BU. Generalized polymorphic eruption with dark red skin and positive Nikolsky’s sign (arrows). (E) Pt. 2 at day 4. Total epidermiolysis on the back. (F) Pt. 2 at day 8. (G) Skin biopsy from Pt. 1 showing intact stratum corneum, while full thickness epidermal necrosis is seen (arrow). Numerous necrotic keratinocytes at all levels of the epithelium is obvious. (H) Skin biopsy from Pt. 2 showing less apoptotic keratinocytes scattered through the epithelium (arrow). Subepidermal bulla formation can be seen (star), with infiltrate of inflammatory cells.

Patient 2 was a 34-year-old male with previously known myotonic dystrophy Type 2, severe obesity and mild obstructive sleep apnea. He was started on ICI for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in September 2021. The patient had an unspecific macular itchy rash Grade 1 (CTCAE) on his back 3 days prior to ICI initiation. He then experienced progressive worsening and developed a generalized exanthema that was diagnosed as TEN 1 week after ICI initiation (). TEN was treated with moderate/high dose (methyl)prednisolone and cyclosporin. Due to declined renal function, cyclosporin was later replaced by mycophenolic mofetil. Re-epithelialization began already at day 6, but the patient died 3 weeks later from complications and subsequent multiple organ failure. Cancer progression was confirmed at autopsy.

A variable degree of epithelial cell necrosis was observed in the biopsies, ranging from focal changes (Patient 2) to full thickness epithelial necrosis with a subsequent epithelial detachment from basal membrane (Patient 1). In both cases, a variable amount of inflammatory cells in the superficial reticular dermis was found and stratum corneum was intact ().

Discussion

Supportive care

As by burn injuries, epithelial detachment makes the TEN patients susceptible for infections and disturbance in fluid balance. Studies indicate a better prognosis if transferred promptly to a burn unit (BU) or an intensive care unit [Citation7]. Treatment includes wound care and infection control, fluid and electrolyte management, nutritional support, pain control, temperature management and, in severe cases, circulatory and respiratory support.

Wound care

Most centers would advise early debridement to remove all loose epidermis. The open wounds are then covered with a dressing, which aids infection control. Modern silver-containing dressings are often used [Citation9]. This decreases the need for painful dressing changes. Alternatives are the use of allografts or synthetic skin substitutes such as Suprathel© [Citation10]. All mucosal surfaces can be affected, including oral mucosa, larynx, esophagus, conjunctiva, cornea, urethra, and vagina. Especially, ocular and vulvovaginal complications are common and should be monitored [Citation11].

Causative treatment

In a pharmacovigilance study of the FEARS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) database, ICIs were significantly associated with an increased risk of SJS/TEN (n = 411; ROR = 2.88, 95% CI: 2.61–3.17) [Citation5], suggesting that ICI may increase the risk of SJS/TEN. In the same article, a meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials including a total of 11597 patients was conducted. In the meta-analysis, treatment with ICIs was associated with an increased risk of SJS/TEN (OR =4.33, 95% CI: 1.90–9.87). In these studies, median time to onset of symptoms was 25.2 days. As demonstrated by our 2 cases, as well as in this meta-analysis, the latency period from ICI treatment to severe skin reactions can span from subacute (<24 h), to several months, necessitating continuous vigilance through and beyond the treatment period. There are few reports on predictive markers for the development of irAEs. In a retrospective study, baseline absolute eosinophil count was significantly associated with a risk of developing skin related irAEs [Citation12].

Recently, a comprehensive overview of current treatment options for cirAEs was published [Citation4]. Still, the majority of studies on ICI related SJS/TEN consists of case reports and case series, and evidence based treatment recommendations are lacking. Both our patients were treated according to ASCO guidelines for immune related Grade 4 severe cutaneous adverse reactions [Citation13]. These include holding further ICI, consulting dermatologist, intravenous (methyl) prednisolone, admittance to BU, consider intravenous immunoglobulin, and cyclosporine as well as optimal intensive supportive and multidisciplinary care. The use of immunomodulating drugs, and in particular corticosteroids, in treatment of classical SJS/TEN has been debated, but resent studies suggest beneficial effect of moderate-high dose corticosteroid therapy if given early in the course of SJS/TEN [Citation14,Citation15]. Infliximab is not specifically mentioned in the ASCO, ESMO, or NCCN treatment guidelines for SJS/TEN. Treatment with TNF alpha inhibitors infliximab and etanercept show promising results in reports raging from case series to RCTs of classical SJS/TEN, but optimal dosing regime and clinical use remains to be further elucidated [Citation16]. Use of infliximab for immunotherapy induced SJS/TEN has been reported [Citation4]. Of note, safety of anti-TNF-alpha therapy in patients with malignancy is a concern, especially in curative Stage 3 patients, and needs to be addressed in further studies.

Recently, the use of immunomodulating drugs, such as prednisolone [Citation17], antibiotics [Citation18], and acetaminophen [Citation19], has been associated with impaired efficacy from immunotherapy and should be used with care. These drugs, in particular prednisolone, are nevertheless indispensable in the setting of potentially life threatening adverse reactions from immunotherapy.

Although disputed [Citation20], it has been suggested that immunotherapy induced SJS/TEN differ from classical SJS/TEN by late onset, mild initial morphologic presentation and rare ocular involvement [Citation21]. A two-hit mechanism was suggested, whereby ICI reduces immune tolerance and induces sensitivity to subsequent drugs. Both our patients had a second potential culprit drug and Patient 1 had relatively mild initial symptoms. Both experienced ocular involvement. Clinically and by histopathology our two cases were regarded and treated as classical TEN. Classical TEN is most frequently triggered by NSAIDS, anti-epileptic drugs and certain antibiotics [Citation22]. Interestingly, Zhu et al., reported that mortality rates among ICI related cases seem to be higher when compared with SJS/TEN caused by other drugs [Citation5]. Some of this effect might be due to age and comorbidity, but the majority of the patients treated with ICI are in ECOG 0-1. This indicates that ICI contribute to the onset of SJS/TEN as well as to the seriousness of the course.

Conclusion

ICI is used in the treatment of a steadily increasing number of cancers, many of which suffered from a desperate lack of effective treatment before the immunotherapy era. Although SJS/TEN are rare complications to ICI treatment, the high mortality rates, prolonged morbidity and need of intensive care unit admissions, demand further investigation into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, predictive biomarkers and risk factors as well as optimal treatment strategies. Our cases underline the importance of early establishment of a multidisciplinary team to implement causal treatment as well as symptomatic and life supportive treatment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- Conroy M, Naidoo J. Immune-related adverse events and the balancing act of immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):392.

- Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721–1728.

- Long GV, Atkinson V, Cebon JS, et al. Standard-dose pembrolizumab in combination with reduced-dose ipilimumab for patients with advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-029): an open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1202–1210.

- Nadelmann ER, Yeh JE, Chen ST. Management of cutaneous immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(1):130.

- Zhu J, Chen G, He Z, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a safety analysis of clinical trials and FDA pharmacovigilance database. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37:100951.

- Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, et al. Current perspectives on Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;54(1):147–176.

- Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, et al. A multicenter review of toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in U.S. burn centers at the end of the twentieth century. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23(2):87–96.

- Downey A, Jackson C, Harun N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: review of pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(6):995–1003.

- Castillo B, Vera N, Ortega-Loayza AG, et al. Wound care for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(4):764–767.

- Lindford AJ, Kaartinen IS, Virolainen S, et al. Comparison of suprathel(R) and allograft skin in the treatment of a severe case of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Burns. 2011;37(7):e67–e72.

- Noe MH, Micheletti RG. Diagnosis and management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38(6):607–612.

- Bai R, Chen N, Chen X, et al. Analysis of characteristics and predictive factors of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. Cancer Biol Med. 2021;18(4):1118–1133.

- Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, in oration with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714–1768.

- Zimmermann S, Sekula P, Venhoff M, et al. Systemic immunomodulating therapies for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):514–522.

- Tsai TY, Huang IH, Chao YC, et al. Treating toxic epidermal necrolysis with systemic immunomodulating therapies: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):390–397.

- Zhang S, Tang S, Li S, et al. Biologic TNF-alpha inhibitors in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systemic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(1):66–73.

- Bai X, Hu J, Betof Warner A, et al. Early use of high-dose glucocorticoid for the management of irAE is associated with poorer survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(21):5993–6000.

- Elkrief A, Derosa L, Kroemer G, et al. The negative impact of antibiotics on outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy: a new independent prognostic factor? Ann Oncol. 2019;30(10):1572–1579.

- Bessede A, Marabelle A, Guegan JP, et al. Impact of acetaminophen on the efficacy of immunotherapy in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2022. DOI:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.05.010

- Choi EC, Heng YK, Lim YL. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(2):e109.

- Molina GE, Yu Z, Foreman RK, et al. Generalized bullous mucocutaneous eruption mimicking Stevens-Johnson syndrome in the setting of immune checkpoint inhibition: a multicenter case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1475–1477.

- Barvaliya M, Sanmukhani J, Patel T, et al. Drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and SJS-TEN overlap: a multicentric retrospective study. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57(2):115–119.