Abstract

Aim

This study examined treatment and survival among women with locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) through comparative analyses of women ≥70 years and those <70 years. The primary endpoint was surgery with curative intention following neoadjuvant therapy. Secondary endpoints were 3-year disease free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), response rates, and adherence to treatment guidelines.

Methods

Patients diagnosed and treated for LABC between 2010 and 2019 at Odense University Hospital, Denmark, were eligible. Surgical information was dichotomized into surgery and no surgery for patients ≥70 years and <70 years, and treatment response was extracted from scan and pathology reports. Adherence to treatment guidelines was registered for the initiated neoadjuvant treatment, and 3-year OS and DFS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier and Log-rank-test.

Results

Of 210 women, 57/102 (55.9%) of those ≥70 years received surgery with curative intent compared with 103/108 (95.4%) of those <70 years. The main reason for omitting surgery was the patient’s request. Fewer women ≥70 years received neoadjuvant therapy according to guidelines compared with their younger counterparts (63.7% versus 98.1%, p < 0.001), but treatment response for women who underwent surgery was similar in both groups. A non-significant difference in 3-year DFS and OS was observed between the groups. Three-year DFS was 80.5% and 73.3%, whereas 3-year OS was 89.6% and 88.7% for patients ≥70 years and <70 years, respectively.

Conclusion

Among women with LABC, women ≥70 years were less likely to receive neoadjuvant therapy according to guidelines. Only half of the patients ≥70 years reached the goal of surgery with curative intent, with no difference in 3-year OS and DFS between age groups.

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, representing nearly 12% of all cancer cases [Citation1], with approximately one-third of patients being diagnosed after 70 years of age [Citation2,Citation3]. The prognosis following breast cancer is determined by various disease-related factors, patient characteristics, and choice of treatment [Citation4].

Although the group of older breast cancer patients is increasing, these patients are often underrepresented in clinical trials [Citation3,Citation5], with only 1–2% of patients enrolled being more than 65 years [Citation5,Citation6]. This challenge contributes to the scarcity of evidence-based treatment in older patients with breast cancer, and treatment is consequently often based on subgroup analyses and extrapolated based on younger patients [Citation7,Citation8]. However, it is unknown whether such extrapolation is appropriate, as the heterogeneity of the older population is considerable, and breast cancer tumor biology differs from that of younger patients [Citation5]. Furthermore, comorbidities leading to competing risks of non-breast cancer mortality and concomitant medication may interact with treatment choices and impact survival [Citation5,Citation8]. It has been suggested that non-adherence to treatment guidelines contributes to the poorer survival seen among older patients due to suboptimal care and inferior treatment than younger patients [Citation3,Citation8,Citation9].

Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is a subset of breast cancer characterized as the most advanced tumors without distant metastases [Citation10]. It includes any T3/T4 tumors and N2/N3 lymph node involvement [Citation11,Citation12]. According to subtype, a multimodality treatment approach is required to manage LABC, consisting of neoadjuvant ± adjuvant chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, ± targeted therapies such as endocrine therapy and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-directed treatments.

Although LABC is more common in older women, little data exist on clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and survival of these patients. Therefore, this study aimed to examine treatment and survival among women with LABC. Comparative analyses of patients 70 years or older and those younger than 70 years were conducted, with the primary endpoint being surgery with curative intention following neoadjuvant therapy. The secondary endpoints were 3-year disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), response rates, adherence to treatment guidelines, and reasons for deviations from those.

Method

This retrospective cohort study was based on data from women diagnosed with LABC between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2019. They were treated at the Department of Oncology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, and identified through the Danish Breast Cancer Group (DBCG) database [Citation13] and the local treatment register.

Data collection and ethics

Baseline characteristics and information on neoadjuvant therapy, treatment response, and surgery were collected from medical records, pathology reports, and scan reports. Data were stored in a secure Sharepoint database after approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (record no. 21/12559) and the Region of Southern Denmark (record no. 21/12084). Due to the observational study design with no intervention for enrolled patients, the ethics committee waived informed consent.

Measures for outcomes

For the primary outcome of surgery with curative intention following neoadjuvant therapy, surgical information was dichotomized into surgery and no surgery for patients ≥70 years and <70 years [Citation3,Citation14,Citation15].

Regarding secondary endpoints, the date of diagnosis was defined as the date of the diagnostic biopsy, and OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause [Citation12]. DFS was defined as the time from surgery to the first relapse (distant or local) or death for any reason [Citation16]. Medical records were reviewed for information on death.

Treatment response was extracted from scan reports and categorized as regression, no change (NC), and progression (PD). The pathological complete response (pCR) rate was also registered. As treatment response was not consistently evaluated by RECIST 1.1 criteria [Citation17], regression was defined as either partial response (PR) or complete response (CR), the latter being assigned when no residual invasive cancer was detected clinically or on preoperative imaging [Citation18].

Guideline treatment was defined as the initiation of standard-of-care following current Danish guidelines [Citation19] and treatment alterations after the first and second evaluations were registered. The first evaluation was performed after two cycles of chemotherapy or approx. 3 months of endocrine therapy, and the second evaluation was performed before surgery.

Adherence to treatment guidelines was registered for the initiated neoadjuvant treatment only. Three main reasons for non-adherence to treatment guidelines were defined before data extraction as patient’s request, age, or comorbidity [Citation14]. Age indicated the treating physician’s convention of the patient being too old/frail to benefit from neoadjuvant therapy and surgery. The patient’s request reflected the patient perspective of treatment benefit, whereas comorbidity was used in cases of comorbidities not complying with medical treatment and/or surgery by a judgment of the treating oncologist.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to summarize data and was reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were calculated using median and range. Categorical data were compared according to age group (≥70 years versus <70 years) using the χ2 test, excluding unknowns. The significance level was set at 0.05. For patients receiving surgery with curative intent, OS and DFS were visualized using Kaplan–Meier plots with 3-year estimates for OS and DFS for the two age groups (≥70 years versus <70 years). Kaplan–Meier curves were compared using the Log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9. 1.1 (225) (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and Excel version 2105 (Microsoft 365, Redmond, WA).

Results

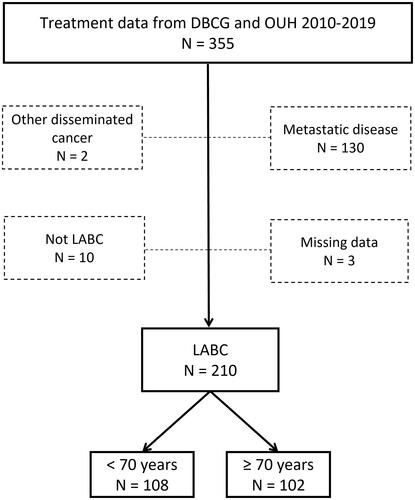

A total of 355 patients were eligible for the study, while 145 were subsequently excluded for different reasons, as shown in , resulting in 210 patients available for analysis. Of those, 102 (48.6%) patients were 70 years or older and 108 (51.4%) patients were younger than 70 years.

Figure 1. A total of 355 women with LABC identified from the DBCG database and treatment files of the Department of Oncology, OUH diagnosed between 2010 and 2019 and treated at OUH, Denmark. Dotted boxes indicate patients excluded from the study. LABC: Locally advanced breast cancer; DBCG: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group; OUH: Odense University Hospital.

Patient and tumor characteristics are shown in . Among 108 women <70 years, 50 (46.3%) were premenopausal, 57 (52.8%) postmenopausal, and one patient had unknown menopausal status. A significantly larger amount of grade III tumors was found in younger patients compared with patients ≥70 years (30.6% versus 14.7%, p = 0.02), while tumor erosion through skin or chest wall (T4 tumor) was more common in women ≥70 years (59.8% versus 20.4%, p < 0.001). In addition, more patients ≥70 years had ER-positive tumors (88.2% versus 68.5%, p < 0.002). We found no difference in the rate of lymph node involvement suspected on diagnostic imaging.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of women diagnosed with locally advanced breast cancer (N = 210).

The median duration of neoadjuvant treatment for patients who underwent surgery was 24 weeks (9–60 weeks). We observed a significant difference in the choice of initiated treatment between the two age groups, with more patients <70 years receiving chemotherapy ± anti-HER2 treatments compared with women ≥70 years (88.9% versus 26.5%, p < 0.001). In contrast, more women ≥70 years received endocrine therapy ± CDK4/6 inhibitors compared with women in the younger age group (71.6% versus 9.26%, p < 0.001) ().

Table 2. Treatment among women diagnosed with locally advanced breast cancer (N = 210).

Surgery

Curative intended surgery was performed in 95.4% (103/108) patients <70 years but only in 55.9% (57/102) of patients ≥70 years (p < 0.001). Five women ≥70 years were inoperable due to inadequate treatment response. In the younger group, two patients were inoperable, and one died before surgery. Significantly fewer women ≥70 years had breast-conserving surgery than younger women (3.51% versus 11.7%, p = 0.04), but no difference was found for axillary lymph node dissection (). We observed no age group-related difference in the number of patients who received accelerated surgery due to progression (p = 0.18).

Survival

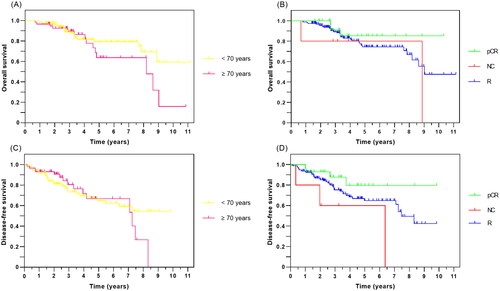

In total, 23.8% (50/210) of patients did not undergo surgery, with a 3-year OS being 35.7%, compared with 75.8% for the total cohort. Three-year OS for those who had surgery were 89.6% and 88.7% for women ≥70 years and <70 years, respectively. For patients undergoing surgery with curative intent, no significant difference was observed for 3-year DFS, being 80.5% for women ≥70 years and 73.3% for women <70 years (). Further, no significant difference in OS and DFS was found between the two age groups or for treatment response (p values > 0.05 for all comparisons).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curves for 160 women with LABC after curative intended surgery showing (A) overall survival according to age group, (B) overall survival according to treatment response, (C) disease-free survival according to age group, and (D) disease-free survival according to treatment response. LABC: locally advanced breast cancer; OS: overall survival; DFS: disease-free-survival; pCR: pathological complete response; NC: no change; R: regression.

Treatment response

More patients <70 years experienced treatment alterations following the first evaluation due to insufficient tumor regression compared with their older counterparts (17.6% (19/108) versus 3.92% (4/102), p = 0.01) (). However, preoperative treatment responses (regression, no change, and progression) were similar across the age groups for women undergoing surgery. Fewer patients ≥70 years achieved pCR at surgery than younger women, 10.5% (6/57) versus 21.4% (22/103, p = 0.08) (). Two patients experienced progression preoperatively, but both underwent surgery.

Table 3. Treatment response and adjuvant therapy among women with locally advanced breast cancer undergoing curative intended surgery (N = 160).

Adherence

Fewer women ≥70 years received neoadjuvant therapy according to guidelines compared with their younger counterparts (63.7% versus 98.1%, p < 0.001). Non-adherence to guidelines was due to age and/or comorbidity in 20 patients ≥70 years (19.6%), while the patient’s request was the reason in 17 patients (16.7%). Two women <70 years (1.85%) refused treatment.

Among women ≥70 years, 45 patients (45/102, 44.1%) did not undergo surgery. The main reason was patient’s request 22/45 (48.9%), while age and/or comorbidity was the reason in 18/45 patients (40.0%). The remaining five women (5/45, 11.1%) were inoperable due to inadequate treatment response.

According to guidelines, adjuvant medical therapy was given in 97.1% of younger women and 94.7% of women ≥70 years. Only 69.8% of patients ≥70 years received radiotherapy as suggested in the guidelines, whereas 96.1% of the younger age group received radiotherapy.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, women ≥70 years were less likely to receive neoadjuvant therapy according to guidelines compared with their younger counterparts, and only half of the patients ≥70 years reached the goal of surgery with curative intent, mainly due to their own request. However, among women who had surgery, no significant difference for 3-year OS and DFS was found between the age groups. Our findings indicate that older women ≥70 years undergoing surgery benefit from the treatment equally to their younger counterparts, at least on a short-term basis.

The strength of this study was the individual review of all extracted patient files, ensuring data quality and follow-up. Further, this study reflects patients with LABC from daily clinical practice, adding important information on differences in treatment and outcomes for older versus younger patients. Weaknesses encounter the retrospective single-center design with a relatively small sample size. In addition, data may be restricted by selection bias or residual confounding, the latter due to incomplete data in terms of medical treatment compliance. As the data were retrospectively collected from medical records, there is a risk of missed information from the medical records and lack of information, for example, performance status and comorbidities. However, these data were inconsistently registered in the medical records, limiting us from further data retrieval.

We observed significant differences in the choice of initiated treatment between the two age groups, with the vast majority of older patients receiving neoadjuvant endocrine therapy ± CDK4/6 inhibitors instead of the chemotherapy regimen suggested in clinical guidelines () [Citation19]. Fewer women in the oldest age group experienced treatment changes after the first evaluation, mainly because many patients in this group were considered unfit for chemotherapy and initiated endocrine therapy. These women had similar response rates as those in the youngest group, indicating that the treatment choices were fair. This finding is in line with previous studies, showing neoadjuvant endocrine therapy ± CDK4/6 inhibitors to be well tolerated and with comparable response rates and surgical and survival outcomes for older patients [Citation20–23].

Research investigating the survival and treatment benefits of older patients with LABC is limited compared with younger patients. Previous studies have compared treatment responses in patients with early breast cancer, including LABC. They found a significantly higher OS rate for patients achieving pCR but no difference in OS between age groups, corresponding with our findings [Citation24,Citation25].

While previous studies have reported 3-year OS for older patients with LABC between 62% and 82% [Citation11,Citation12], a recent study by Klein et al. [Citation25] found a 2-year OS of 95% and a 2-year recurrence-free survival of 85% for LABC patients undergoing surgery following neoadjuvant therapy. Despite the reported 2-year estimates and a lower mean age of patients, the findings of Klein et al. [Citation25] seem comparable to those of this study. The differences in OS reported may be due to differences in age span and fewer patients receiving surgery, as seen in a study by Hornova et al. [Citation12], whereas a previous study from our institution by Cold et al. is more in line with the present findings [Citation11].

As women age, comorbidities increase, with an increased risk of non-cancer mortality. Of the 50 patients who did not undergo surgery in this study, 45 were 70 years or older. In addition, they were approximately 5 years older than those receiving surgery. Our observations align with a previous report in which 80% of patients ≥70 years, in whom surgery was omitted, had multiple health issues [Citation26]. Therefore, we might speculate that the group of women ≥70 years who underwent surgery in this study was somehow preselected compared with the younger and more fit patients who underwent surgery. However, as registration of comorbidities, regular medication, and performance status was not feasible, it limits us from further analysis. Moreover, significantly more patients ≥70 years had ER-positive tumors, which might have influenced treatment decisions for the older patients not undergoing surgery.

We found that the patient’s request was the reason for omitting surgery in nearly 50% of cases, whereas age and/or comorbidities were the reason in 40%. Previous studies report that patient request account for 32–58% of patients in whom surgery was omitted [Citation26,Citation27].

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) may improve compliance and treatment tolerability in patients [Citation26] and has been suggested as a possible useful approach, especially concerning older and/or frail cancer patients [Citation28]. A multidisciplinary oncological and geriatric approach may aid in optimizing the treatment, considering patient’s preferences, and ensuring the quality of life [Citation8].

Evidence suggests that management of breast cancer in older women tends not to follow national guidelines, often resulting in the omission of surgery despite a lack of clinical reasoning [Citation29] or fear of increased postoperative mortality [Citation30]. However, the general approach to treating older women with breast cancer should be based on an overall assessment of benefits and risks for the individual patient taking patient preferences, potential comorbidities, and breast cancer subtype into account [Citation29,Citation31].

Future research should focus on patient-centered shared decision-making, the impact of CGA in older frail patients, or alternative, less toxic treatment options in the neoadjuvant setting, i.e., endocrine therapy ± CDK4/6 inhibitors.

Conclusion

In this retrospective cohort study, women ≥70 years were less likely to receive neoadjuvant therapy according to guidelines. Only half of the patients ≥70 years reached the goal of surgery with curative intent, with no difference in 3-year OS and DFS between age groups. Our findings indicate that older women ≥70 years undergoing surgery benefit from the treatment equally to their younger counterparts, at least on a short-term basis.

Ethical approval

Data were stored in a secure Sharepoint database after approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (record no. 21/12559) and the Region of Southern Denmark (record no. 21/12084). Due to the observational study design with no intervention for enrolled patients, the ethics committee waived informed consent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249.

- Derks MGM, Bastiaannet E, Kiderlen M, et al. Variation in treatment and survival of older patients with non-metastatic breast cancer in five European countries: a population-based cohort study from the EURECCA breast cancer group. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(1):121–129.

- Jensen JD, Cold S, Nielsen MH, et al. Trends in breast cancer in the elderly in Denmark, 1980–2012. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(1):59–64.

- Land LH, Dalton SO, Jørgensen TL, et al. Comorbidity and survival after early breast cancer. A review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;81(2):196–205.

- Van De Water W, Bastiaannet E, Dekkers OM, et al. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival in patients with early-stage breast cancer by age at diagnosis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(6):813–820.

- Hillner BE, Mandelblatt J. Caring for older women with breast cancer: can observational research fill the clinical trial gap? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(10):660–661.

- Angarita FA, Chesney T, Elser C, et al. Treatment patterns of elderly breast cancer patients at two Canadian cancer centres. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 May;41(5):625–634.

- Biganzoli L, Wildiers H, Oakman C, et al. Management of elderly patients with breast cancer: updated recommendations of the international society of geriatric oncology (SIOG) and European society of breast cancer specialists (EUSOMA). Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):e148–e160.

- Weggelaar I, Aben KK, Warlé MC, et al. Declined guideline adherence in older breast cancer patients: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Breast J. 2011;17(3):239–245.

- Garg PK, Prakash G. Current definition of locally advanced breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(5):409–410.

- Cold F, Svolgaard O, Thygesen PH, et al. 461 Locally advanced breast cancer; twelve years results from a single institution. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2010;8(3):193–194.

- Hornova J, Bortlicek Z, Majkova P, et al. Locally advanced breast cancer in elderly patients. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2017;161(2):217–222.

- Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B, Jensen M-B, et al. Danish breast cancer cooperative group. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:445–449.

- Vogsen M, Bille C, Jylling AMB, et al. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival in older women with early-stage breast cancer in Denmark 2008–2012. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(7):741–747.

- Biganzoli L, Battisti NML, Wildiers H, et al. Updated recommendations regarding the management of older patients with breast cancer: a joint paper from the European society of breast cancer specialists (EUSOMA) and the international society of geriatric oncology (SIOG). Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):e327–e340.

- Saad ED, Squifflet P, Burzykowski T, et al. Disease-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in patients with HER2-positive, early breast cancer in trials of adjuvant trastuzumab for up to 1 year: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):361–370.

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247.

- Koh J, Kim MJ. Introduction of a new staging system of breast cancer for radiologists: an emphasis on the prognostic stage. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20(1):69–82.

- Jensen MB, Laenkholm AV, Offersen BV, et al. The clinical database and implementation of treatment guidelines by the Danish breast cancer cooperative group in 2007–2016. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(1):13–18.

- Cao L, Sugumar K, Keller E, et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy as an alternative to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients: pathologic and surgical outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(10):5730–5741.

- Delaloge S, Dureau S, D’Hondt V, et al. Survival outcomes after neoadjuvant letrozole and palbociclib versus third generation chemotherapy for patients with high-risk oestrogen receptor-positive HER2-negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2022;166:300–308.

- Prat A, Saura C, Pascual T, et al. Ribociclib plus letrozole versus chemotherapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, luminal B breast cancer (CORALLEEN): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(1):33–43.

- Goetz MP, Okera M, Wildiers H, et al. Safety and efficacy of abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in older patients with hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer: an age-specific subgroup analysis of MONARCH 2 and 3 trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;186(2):417–428.

- Battisti NML, True V, Chaabouni N, et al. Pathological complete response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy in 789 early and locally advanced breast cancer patients: the royal Marsden experience. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;179(1):101–111.

- Klein J, Tran W, Watkins E, et al. Locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):306.

- Verholt AB, Foss ACH, Christiansen P, et al. Non-surgically treated older women with operable early breast cancer in Denmark. Dan Med J. 2020;67(11):A04200226.

- Hamaker ME, Bastiaannet E, Evers D, et al. Omission of surgery in elderly patients with early stage breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):545–552.

- Fusco D, Allocca E, Villani ER, et al. An update in breast cancer management for elderly patients. Transl. Cancer Res. 2018;7(S3):S319–S328.

- Tesarova P. Breast cancer in the elderly—should it be treated differently? Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2012;18(1):26–33.

- Rocco N, Rispoli C, Pagano G, et al. Breast cancer surgery in elderly patients: postoperative complications and survival. BMC Surg. 2013;13(S2):S25.

- Katz SJ, Belkora J, Elwyn G. Shared decision making for treatment of cancer: challenges and opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):206–208.