Abstract

Background

Despite structural and cultural similarities across the Nordic countries, differences in cancer survival remain. With a focus on similarities and differences between the Nordic countries, we investigated the association between socioeconomic position (SEP) and stage at diagnosis, anticancer treatment and cancer survival to describe patterns, explore underlying mechanisms and identify knowledge gaps in the Nordic countries

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of population based observational studies. A systematic search in PubMed, EMBASE and Medline up till May 2021 was performed, and titles, abstracts and full texts were screened for eligibility by two investigators independently. We extracted estimates of the association between SEP defined as education or income and cancer stage at diagnosis, received anticancer treatment or survival for adult patients with cancer in the Nordic countries. Further, we extracted information on study characteristics, confounding variables, cancer type and results in the available measurements with corresponding confidence intervals (CI) and/or p-values. Results were synthesized in forest plots.

Results

From the systematic literature search, we retrieved 3629 studies, which were screened for eligibility, and could include 98 studies for data extraction. Results showed a clear pattern across the Nordic countries of socioeconomic inequality in terms of advanced stage at diagnosis, less favorable treatment and lower cause-specific and overall survival among people with lower SEP, regardless of whether SEP was measured as education or income.

Conclusion

Despite gaps in the literature, the consistency in results across cancer types, countries and cancer outcomes shows a clear pattern of systematic socioeconomic inequality in cancer stage, treatment and survival in the Nordic countries. Stage and anticancer treatment explain some, but not all of the observed inequality in overall and cause-specific survival. The need for further studies describing this association may therefore be limited, warranting next step research into interventions to reduce inequality in cancer outcomes.

Study registration

Prospero protocol no: CRD42020166296

Introduction

Cancer has in recent years become one of the leading causes of death in high-income countries, including the Nordic countries [Citation1]. Despite structural and cultural similarities of the Nordic welfare states, differences between the countries have been documented both in cancer incidence and survival [Citation2,Citation3]. Although shorter and longer education as well as both primary and secondary health care is tax-funded and requires no or relatively low co-payment, patients with low socioeconomic position (SEP) have considerably lower cancer survival in all Nordic countries compared to patients with higher SEP [Citation4–10]. This socioeconomic inequality in cancer has been documented for most frequent cancers [Citation6,Citation10].

SEP is a complex concept describing patients’ social and economic position in society [Citation10]. SEP is related to a wide range of health factors, such as symptom perception and recognition, health care seeking behavior, adherence to health- and lifestyle recommendations, communication with health care professionals and participation in screening programs [Citation10]. These factors may translate into socioeconomic differences in stage at diagnosis, comorbidity and access to treatment [Citation11–14], which are reported to be the main drivers of the socioeconomic inequality in cancer survival [Citation15].

Examining patterns of socioeconomic inequality at key points in the cancer trajectory, and across countries that have differences in cancer survival despite similar welfare and health care, will provide an opportunity to discuss possible underlying mechanisms that may be targeted in clinical practice. The aim of this study is therefore to summarize the literature, describe patterns and identify knowledge gaps concerning associations between SEP and stage at cancer diagnosis, anticancer treatment and cancer survival in the Nordic countries.

Methods

Protocol and registration

A study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO portal (CRD42020166296) before initiation of the study. The review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation16].

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE and Medline up till May 2021. The search was adapted to each database and was limited to literature on humans and literature published after January 1st, 2005. A search in PROSPERO and the Cochrane library ensured that there were no ongoing systematic reviews on the topic. Covidence and Endnote software X9 were used to manage references. The specific search strings for each database are available upon contact to the authors.

Study eligibility

Studies with observational design, including cohort or cross-sectional studies, which were published in peer-reviewed journals in English, Danish, Swedish or Norwegian language were eligible for inclusion. Studies had to be population-based including persons aged 18 years and above, diagnosed with cancer and resident in either Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Greenland or the Faroe Islands. To be eligible, the studies should report on at least one of the following outcomes: stage at diagnosis, anticancer treatment or survival after cancer (relative survival or ratios of risk, rates or odds). SEP had to be measured as education or income (individual or household level).

Study selection

All studies from the searches were independently screened for eligibility by two authors; first by title, secondly by abstract and finally by full-text. Any disagreements at any phase of the screening were resolved by discussion with a third author. The software ‘Covidence’ was used to manage the screening process.

Data items and extraction

Data extraction was carried out by one author and double-checked by another author. The following data was extracted: author, year of publication, country, study design, setting, inclusion period, number of participants, definition of SEP, effect measurement, confounding variables and estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or p-values for the highest and lowest category of SEP for relevant outcomes (stage at diagnosis, treatment, survival). Data for the crude/least adjusted and most adjusted estimates were extracted when available. In studies reporting both 1-year, 5-year or 10-year survival, 5-year survival was prioritized. If studies provided several measures of survival, estimates for both cancer-specific, relative and overall survival were extracted.

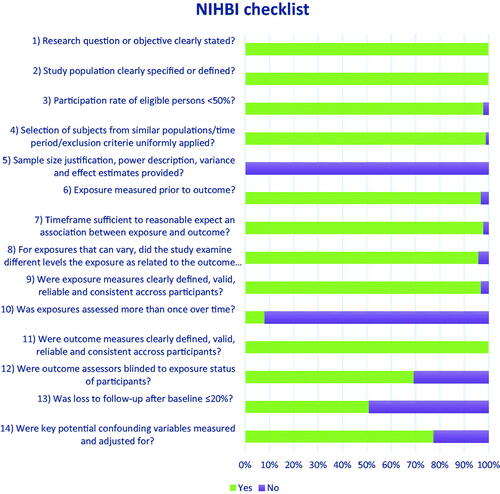

Study quality

Study quality were appraised in accordance with the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies provided by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools). Study quality was evaluated by one author and double-checked by another author. An overview of the quality of included studies can be seen in .

Summary measures and synthesis of results

All extracted data is presented in summary tables for each study outcome; stage at diagnosis, anticancer treatment and survival (Supplementary material, table S1, S2, S3). Where estimates were hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR), data was uploaded to the statistical software R, version 4.1.0, packages ‘readxl, ggplot2, Rcolorbrewer’ [Citation17], and presented graphically in focused forest plots for each outcome. To enhance comparability between studies for the forest plots, estimates were inverted if the exposure reference group was the highest SEP category, well aware that this may be problematic for exposure variables with more than 2 levels. All original estimates are found in the result tables.

Results

Included studies

The search resulted in 3629 hits. We excluded 179 duplicates and 3193 studies through title and abstract screening, which left 257 studies to be assessed in full text for eligibility. After full-text screening we included 98 studies in the review (see PRISMA flow diagram, ). Study characteristics of the included studies are reported in , and detailed results are presented in Table S1, S2 and S3 in supplementary materials. It was possible to present the results of 55 studies which provided comparable estimates in forest plots, whereas all studies contribute to qualitative analyses. The quality of the included studies was generally high in criteria relevant to register based studies ().

Figure 2. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation15] flow diagram over the review process showing number of included and excluded studies with reasons [Citation16].

![Figure 2. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation15] flow diagram over the review process showing number of included and excluded studies with reasons [Citation16].](/cms/asset/52c6493e-a6e2-4375-9545-fbfcb2a76c6e/ionc_a_2143278_f0002_c.jpg)

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

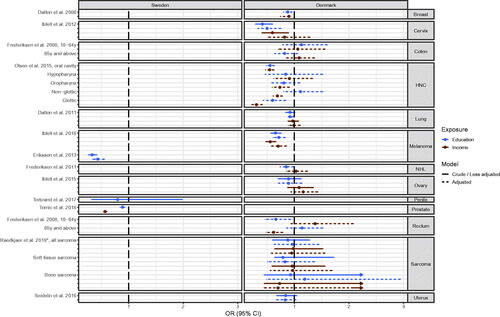

Stage at diagnosis

Of the 14 studies examining the association between SEP and stage at diagnosis (Table S1), 13 studies reported ORs and are presented in [Citation11–13,Citation26,Citation54,Citation55,Citation68,Citation69,Citation79,Citation80,Citation83,Citation85,Citation93]. Results were reported from two countries and multiple cancer sites; 10 studies from Denmark (cancers of the breast [Citation68], cervix [Citation83], colon [Citation80], head and neck [Citation12], lung [Citation69], melanoma [Citation85], Non-Hodgkin lymphoma [Citation79], ovaries [Citation11], rectum [Citation80], sarcoma [Citation93] and uterus [Citation13]) and 4 studies from Sweden (breast cancer [Citation48], melanoma [Citation26], penis [Citation55] and prostate cancer [Citation54]) (Table S1).

Figure 3. Odds ratio (OR) of late stage at diagnosis for cancer patients with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by cancer site and country. Estimates on the left of OR = 1.00 favors high SEP. *disseminated stage vs. localized stage

Long education and high income were associated with lower odds for late stage in eight out of 13 studied cancer sites [Citation12,Citation26,Citation48,Citation54,Citation68,Citation69,Citation79,Citation83,Citation85] (). In five out of 13 cancer sites, namely in cancer of the colon [Citation80], ovary [Citation11], penis [Citation55], sarcoma [Citation93] and for uterus [Citation13] no risk estimates indicated an association, and for rectum cancer the direction of associations differed by age group and SEP-indicator [Citation80]. Further, the results for cancer of the lung [Citation68] and head & neck [Citation11] were inconsistent, depending on exposure or anatomical sub-site of the cancer, respectively ( and Table S1).

Anticancer treatment

The various anticancer treatments represented in the included studies are curatively/palliatively intended, salvage/non-salvage therapy, surgery (including acute/elective), adjuvant/neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, Tyrasine Kinase Inhibitors, radiotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplant, and hormonal/endocrine treatment (Table S2).

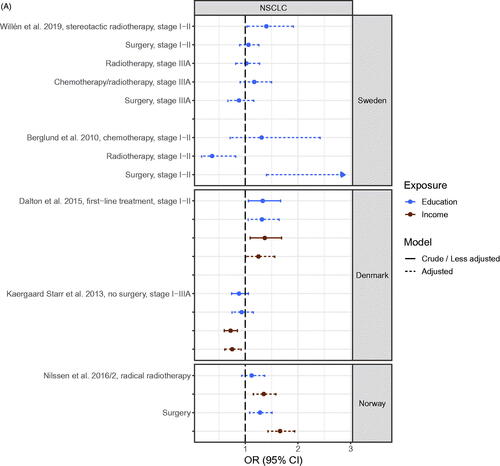

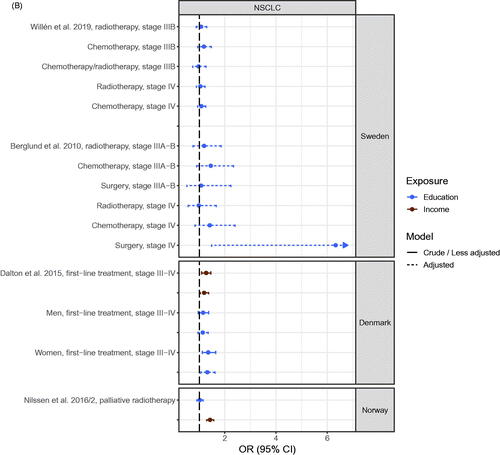

Of the 24 studies which included anticancer treatment as an outcome (Table S2), 23 studies reported OR [Citation14,Citation19,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation40–42,Citation44–46,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58–60,Citation63,Citation73,Citation74,Citation87,Citation97,Citation100,Citation108] and 20 of these were possible to present in , 1SA and 2S [Citation14,Citation19,Citation27,Citation28,Citation40–42,Citation44,Citation45,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58–60,Citation63,Citation73,Citation74,Citation87,Citation100,Citation108]. Inapplicability for presentation in figures was due to results being presented for all cancers combined [Citation46,Citation97], using the middle category as reference [Citation30] or using an incompatible effect measure [Citation36]. Results were reported from four countries on multiple cancer sites; 16 studies from Sweden (cancers of rectum [Citation44,Citation45], prostate [Citation41,Citation42,Citation54], breast [Citation27,Citation28,Citation56,Citation58,Citation60], esophagus [Citation40], lung [Citation19,Citation59], all sites [Citation46], lymphoma [Citation30] and leukemia [Citation36]), 5 studies from Denmark (colorectal cancer [Citation74], lymphoma [Citation14,Citation63], and lung cancer [Citation73,Citation87]), 2 studies from Norway (lung cancer [Citation100] and all-sites [Citation97]) and one study from Finland (prostate cancer [Citation108]). In general, income showed stronger associations than education for anticancer treatment (, Figures 1SA and 2S).

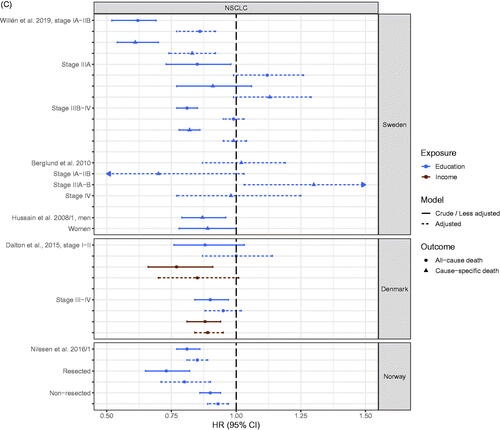

Figure 4. (A) Odds ratio (OR) of receiving anticancer treatment for patients with early stage NSCLC with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by country. Estimates on the right of OR = 1.00 favors high SEP. (B) Odds ratio (OR) of receiving anticancer treatment for advanced stage NSCLC patients with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by country. Estimates on the right of OR = 1.00 favors high SEP. (C) Hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause or cause-specific death in NSCLC patients with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by country. Estimates on the left of HR = 1.00 favors high SEP.

The cancer site that was studied most was lung cancer (Table S2). Results of analyses of receiving versus not receiving anticancer treatment (radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy) for early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [Citation19,Citation59,Citation73,Citation87,Citation100] showed a pattern with results generally favoring patients with high SEP. Most clear was a higher risk of receiving surgery (or lower risk of not receiving surgery) for patients with high SEP [Citation19,Citation73,Citation87,Citation100]. Of the 20 estimates, 18 favored high SEP with 11 being statistically significant and 7 being statistically insignificant or being close to the line of no difference, while two estimates favored low SEP (). For late-stage NSCLC, estimates favored patients with high SEP regardless of anticancer treatment type, although 13 out of 19 estimates were non-significant () [Citation19,Citation59,Citation73,Citation100].

The odds of receiving surgery or radiotherapy among patients by SEP for rectal cancer was studied in two Swedish studies [Citation44,Citation45] and risk of acute versus elective surgery (acute surgery carries higher risk of complications and is an adverse outcome compared to elective surgery) for colon cancer in one Danish study [Citation74] (Figure 1SA). Out of the 30 estimates, 21 estimates favored patients with high SEP and 11 of these were statistically significant [Citation44,Citation45,Citation74] (Figure 1SA). In the two Swedish studies [Citation44,Citation45] (Figure 1SA), the estimates favored patients with low SEP in four out of ten estimates when the SEP indicator was education whereas the estimates favored patients with low SEP in nine out of 10 estimated when the SEP indicator was income. In the Danish study the estimate for acute versus elective surgery favored high SEP for all age groups combined, and more pronounced for the youngest age group [Citation74].

Differences in anticancer treatment for prostate cancer was examined in three studies from Sweden [Citation41,Citation42,Citation54] and one study from Finland [Citation108] (Figure 2S). Results showed a pattern of patients with high SEP having a higher odds of receiving chemotherapy, curatively intended treatment, and radical prostatectomy compared to patients with low SEP [Citation40,Citation41,Citation54,Citation56,Citation108] (Figure 2S). The same was the case for radiotherapy among patients with metastatic or locally advanced prostate cancer, while there was no apparent association between receiving radiotherapy and SEP among patients with low, intermediate or high-risk prostate cancer [Citation108]. Conversely, the odds for receiving hormonal therapy was higher in patients with low SEP [Citation42].

Five studies investigated breast cancer treatment, all from Sweden [Citation27,Citation28,Citation56,Citation58,Citation60] (Figure 2S). Estimates did not consistently reach statistical significance, but indicated a tendency favoring patients with high SEP in terms of receiving chemotherapy vs none, breast conserving surgery vs. mastectomy and adherence to endocrine treatment versus non-adherence [Citation27,Citation28,Citation56,Citation58,Citation60] (Figure 2S). Only one study examined SEP and chemotherapy among breast cancer survivors [Citation56].

The remaining studies were from Denmark (two studied Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma) [Citation14,Citation63], Sweden (one studied esophagus cancer [Citation40], one Mantle Cell Lymphoma [Citation30], one Chronic Myeloid Leukemia [Citation36] and one all-sites [Citation46]) and Norway (one study of all sites [Citation97]). Although only few estimates reached statistical significance, in fact only two out of ten estimates for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma were statistically significant, results still consistently favored patients with high SEP in regards to all types of anticancer treatment (receiving immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy versus none, curatively intended vs palliative treatment, and chemotherapy + stem cell transplant vs. no treatment) (Figure 2S and Table S2).

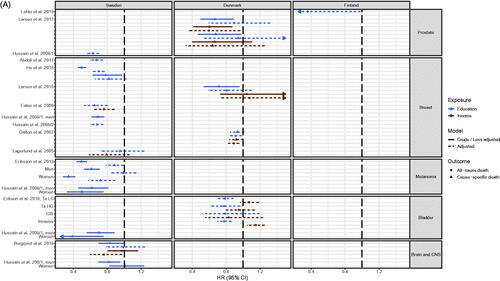

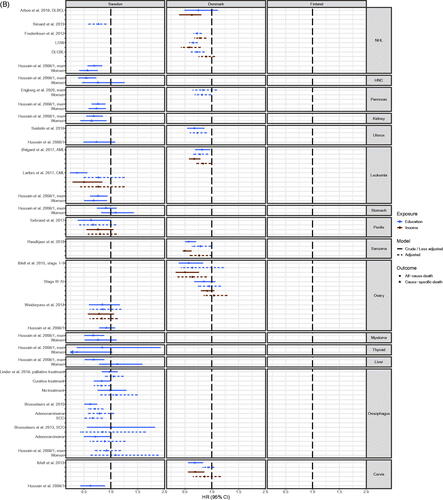

Survival

Seventy-three studies reported cause-specific and/or all-cause survival (Table S3), and the majority presented HRs or ORs and were compatible for presentation in figures ( (NSCLC) [Citation19,Citation34,Citation59,Citation73,Citation101], 1SB (colorectal cancer) [Citation34,Citation43,Citation51,Citation74,Citation82] and 5 A [Citation18,Citation20,Citation25,Citation26,Citation32–35,Citation71,Citation78,Citation88,Citation89,Citation110] and 5B [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14,Citation22,Citation23,Citation34,Citation36,Citation40,Citation50,Citation55,Citation57,Citation62,Citation76,Citation84,Citation92,Citation93] (all other cancer sites)). Estimates from 31 studies with incompatible outcome measures or estimates for all cancer sites combined could not be included in figures [Citation21,Citation24,Citation31,Citation37–39,Citation47,Citation49,Citation52,Citation53,Citation61,Citation64–67,Citation70,Citation72,Citation75,Citation77,Citation81,Citation86,Citation90,Citation91,Citation94–96,Citation99,Citation103,Citation105,Citation106,Citation109].

Studies from Sweden (n = 30) [Citation18–26,Citation29,Citation31–40,Citation43,Citation47,Citation49–53,Citation55,Citation57,Citation59], Denmark (n = 32) [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14,Citation29,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64–67,Citation70–78,Citation81,Citation82,Citation84–86,Citation88–96], Finland (n = 6) [Citation29,Citation106,Citation107,Citation109–111] and Norway (n = 8) [Citation29,Citation98,Citation99,Citation101–105] examined survival as an outcome and covered multiple cancer sites (Table S3, , Citation5(A,B), Figure 1SB). The most frequently studied cancer sites were breast cancer with 19 studies [Citation18,Citation21,Citation25,Citation29,Citation31–35,Citation67,Citation70,Citation71,Citation89,Citation98,Citation102–105,Citation109] (Table S3 and ), lung cancer with 13 studies [Citation19,Citation34,Citation38,Citation49,Citation53,Citation59,Citation70,Citation72,Citation73,Citation98,Citation99,Citation101,Citation103] (Table S3 and ) and colorectal cancer with 13 studies [Citation24,Citation34,Citation43,Citation51,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75,Citation81,Citation82,Citation98,Citation103,Citation106] (Table S3 and Figure 1SB).

Figure 5. (A) Hazard Ratio (HR) for all-cause or cause-specific death in cancer patients with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by cancer site and country. Estimates on the left of HR = 1.00 favors high SEP. LG: low grade; HG: high grade; CIS: carcinoma in situ; (B) Hazard Ratio (HR) for all-cause or cause-specific death in cancer patients with high socioeconomic position (SEP) compared to patients with low SEP in the Nordic countries, by cancer site and country. Estimates on the left of HR = 1.00 favors high SEP. DLCBL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; LOW: Low grade; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; CML: Chronic myeloid leukemia; SCC: Squamous-cell carcinoma.

Five studies of lung cancer were compatible for presentation (). In the Danish and Norwegian studies, a clear pattern of better overall survival for lung cancer patients with high SEP was apparent [Citation73,Citation101] (). In the Swedish studies a more mixed pattern was found and also outcomes covered both overall and cause-specific survival. Here, the associations across studies were weaker, as only eight out of the eleven estimates that favored patients with high SEP were statistically significant and one estimate with a wide confidence interval significantly favored patients with low SEP. Four estimates were very close to the line of no difference [Citation19,Citation34,Citation59] ().

Studies in colorectal cancer were of Swedish, Danish and Finish origin, and consistently showed that patients with high SEP had substantially better overall and cause-specific survival [Citation24,Citation34,Citation43,Citation51,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75,Citation81,Citation82,Citation98,Citation103,Citation106] (Table S3 and Figure 1SB).

The same association was found for most other studied cancer sites when looking at overall survival, with a few exceptions (Table S3, ). Very few of the adjusted estimates for cause-specific survival reached statistical significance [Citation25,Citation26,Citation34,Citation50] (Table S3, ). The most marked exception was a Swedish study in penis cancer, where low-precision estimates for cause-specific survival tended to favor patients with low SEP [Citation55] (Table S3 and ). Furthermore, studies in breast, bladder and cervix cancer were not consistent across countries (Table S3, ). For example, Swedish studies of breast, bladder or cervix cancer showed a pattern of better overall and cause-specific survival for patients with high SEP [Citation18,Citation25,Citation32–35], while the Danish studies of breast, bladder or cervix cancer varied according to SEP indicator used, as high education was associated with better overall survival whereas high income was not when looking at adjusted estimates [Citation71,Citation78,Citation84,Citation89] (). For cancers of the esophagus and stomach, we did not find a consistently significant association between SEP and overall or cause-specific survival, respectively [Citation22,Citation23,Citation34,Citation40] (). Finally, for patients with pancreatic cancer, those with high SEP had a statistical significant better cause-specific survival than patients with low SEP [Citation34].

Discussion

Principal findings

In this systematic review, we present an overview of the evidence of socioeconomic inequality in cancer in the Nordic Countries. Based on generally high-quality studies, it shows an association between low SEP and late stage at diagnosis, receiving less favorable anticancer treatment and poorer overall and cause-specific survival. The results were quite consistent across studies from Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway and across cancer types.

Interpretation of results

Stage of diagnosis

Results from this study show socioeconomic inequalities in stage at diagnosis across cancer types in the Nordic countries. Suggested explanations to this may be delays in diagnosis due to i.e. symptom debut perception and health literacy [Citation15,Citation112]. Health literacy has implications for how persons interpret symptoms and how they act in response. This may delay a consultation with a doctor and thereby prolonging the time from symptom debut to diagnosis, allowing the cancer to progress to more advanced stages. It may also impact the way people communicate with health professionals as well as how the health professionals respond.

Another possible explanation is the presence of more comorbidity among socioeconomically deprived people [Citation15,Citation112]. If a patient suffers more competing illnesses, symptoms may be muddled and new symptoms may be harder to detect. Further, for the health professional caring for the multi-morbid patient, it may be equally difficult to distinguish symptoms of a new cancer from symptoms of progressive non-cancer morbidity.

Finally, a likely explanation for the socioeconomic inequality in stage at diagnosis may arise from an unequal participation in screening, which is relevant for major cancer types like cervical [Citation113], breast [Citation114] and colorectal cancer [Citation115]. It has been suggested that patients with low SEP generally have more negative beliefs about screening, early detection and treatment, worrying that a diagnosis and treatment is worse than the cancer itself, which may lead to inappropriate health behavior and nonparticipation in screening [Citation15].

Anticancer treatment

Overall, we found the same socioeconomic inequality in anticancer treatment as described for stage, despite high-quality health care being considered accessible and free to all residents in the Nordic countries. Early-stage diagnosis increases chances of being offered curatively intended treatment, whereas later stage diagnosis leads to fewer treatment options. Further, the increased frequency of comorbidity in patients with low SEP also reduces the treatment options available due to poorer health and performance status leading to worse treatment tolerance and post-treatment recovery [Citation15,Citation112]. However, even in the studies where analyses were adjusted for stage and comorbidity, we still found consistent inequalities in receipt of anticancer treatment.

In universal healthcare systems, aside from stage, comorbidity and general health status, other factors may influence the offered anticancer treatment, such as age, the oncologist’s subjective evaluation of treatment tolerance, geographical area and distance to available treatments. However, our findings mostly align with those of a systematic review and meta-analysis about socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer treatment by Forrest et al. [Citation116] showing that lower SEP was associated with less access to surgery and chemotherapy in both universally funded healthcare systems and insurance financed healthcare systems. This indicates that there may be explanatory factors for socioeconomic inequality yet unaccounted for, and that the type and structure of the healthcare system may only play a smaller role. Health literacy and other mechanisms involved in the interaction between the patient and health professionals such as social capital may be equally important in explaining inequality in the treatment offered, but this has earned little focus in research.

Survival

Results from this review are in alignment with the findings of previous reviews from 1997 and 2006 [Citation117,Citation118], reporting that low SEP is associated with poorer cancer survival. Still, the mechanisms behind this association remains incompletely understood. Strong mediators of the association has been proposed to include stage at diagnosis, comorbidity and access to anticancer treatment, although the mediating effect of stage at diagnosis actually differs across cancer sites and between countries [Citation117,Citation119]. We observed a strong association between low SEP and worse overall survival and a similar but less strong association with cause-specific survival in the Nordic countries independent of stage at diagnosis in this review (Table S1). Some of the included studies took anticancer treatment into account when analyzing the association between SEP and survival [Citation19,Citation23,Citation25,Citation36,Citation40,Citation49,Citation59,Citation73,Citation74,Citation92,Citation101,Citation103,Citation109], but the significant socioeconomic difference in both overall and cause-specific survival persisted. Further, the associations remained significant after adjusting for comorbidity, which was done in one-third of studies [Citation11,Citation13,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation32,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation49,Citation55,Citation59,Citation65,Citation71,Citation73,Citation74,Citation76,Citation81,Citation82,Citation88,Citation89,Citation93,Citation100]. In most of the studies presenting both crude and adjusted estimates, adjusting for comorbidity did not affect the estimates. However, this was sometimes slightly different for early and late stage disease with either a weakening or strengthening impact.

Taken together, stage, anticancer treatment and comorbidity explain some, but not all of the observed socioeconomic inequality in overall and cause-specific survival.

Looking beyond the Nordic countries, a recent systematic review by Afshar and colleagues [Citation15] included besides stage and anticancer treatment also tumor characteristics, lifestyle behavior (i.e. alcohol intake and smoking), comorbidity, health-seeking behavior, rural/urban distribution, ethnicity, and access to health care [Citation15]. The authors found that differences in disease stage, tumor characteristics, lifestyle behavior, comorbidity, and anticancer treatment were consistently reported as mediating factors of socioeconomic inequalities in cancer-specific survival. However, in alignment with our results, the mediating impact of these factors on the socioeconomic differences in survival varied depending on cancer sites; in breast cancer, early stage at diagnosis seemed to be a major determinant of better survival, while in colorectal cancer, emergency presentation and comorbidity seemed to be more important [Citation15]. Despite our findings of SEP being associated with survival across all cancer types, the mechanisms behind this finding seem to differ according to cancer type, probably related to differences in patient population and aggressiveness of disease, both within and beyond the Nordic countries.

Another mediating factor which might influence survival and also be associated with SEP is quality of life (QOL), which has been the subject of previous studies over the past 20 years [Citation120–122]. It has not so far been explored in the Nordic countries, most likely because these studies are often register-based and QOL data are not systematically collected in registries. However, in a systematic review including 104 studies, the authors found that better pretreatment QOL was associated with increased cancer survival [Citation121]. Further, another systematic review with 10,108 patients contributing to independent patient data meta-analysis across cancer types, found that QOL, sociodemographic and clinical factors were strongly associated with survival in patients with cancer, although some QOL domains (appetite loss, fatigue, physical function and pain) were more strongly associated with survival than others and this again differed across cancer types [Citation122]. Data was pooled from randomized clinical trials, and lends strong support to the relevance of including QOL when examining the intricate mechanisms involved in inequality in cancer survival.

Strengths and limitations

SEP is a complex construct, and no single measure contains all aspects [Citation10]. In research examining health inequalities according to SEP, previous studies have suggested that the choice of SEP indicator may not be of substantial importance, as they by large will show the same associations [Citation11]. However, different indicators may reveal different strengths of associations [Citation10]. We included both SEP measured as education and income, which are well recognized and frequently used measurements of SEP. It varied only slightly which of the two measures had the strongest association to the different cancer outcomes, and studies using other SEP measures have consistently found similar associations [Citation121].

A strength of this study is that we included studies from countries that have longstanding nationwide cancer registration. Further, information on vital status, education and income in the Nordic countries is well documented at an individual level, which minimizes misclassification substantially. However, clinical data in the registries vary according to cancer type, and consequently so did the included studies in terms of adjustment for covariates. Thus, not all of the studies included details on stage at diagnosis, histology, comorbidity and anticancer treatment. Consequently, the estimates presented in forest plots have not been consistently adjusted for the same covariates, and direct comparisons may therefore be hampered. Similarly, it may be considered a limitation that we did assess publication bias in this systematic review, but most included studies were large-scale, population-based and register-based and in these study designs risk of publication bias is generally considered to be low.

We only identified and included studies published from 2005-2021, but they contained patients diagnosed between 1977 and 2017, with the majority of patients diagnosed in the 2000s. As anticancer treatment has advanced vastly with time, older study populations may be less relevant to current clinical practice.

In this review several of the included studies reported overall and not cancer-specific survival. With the inclusion of overall survival as an outcome, we might capture other elements of socioeconomic inequality, as there is solid evidence that SEP is also associated with death from other causes than cancer [Citation123]. Finally, inequality in cancer includes more aspects than could be the focus of this study, and especially inequality in access to rehabilitation and end-of-life care deserves enhanced attention [Citation124]. It is likely that this aspect would shed further light on the association between SEP and survival in patients with cancer.

Next steps

While we consistently found inequality in cancer stage at diagnosis, anticancer treatment and survival for several cancer types in the Nordic countries, mechanisms behind these differences remain largely unknown. This calls for further research into what happens in the interaction between the patient and the health care system. A qualitative study suggests that the current health discourse might be less appropriate in groups of low SEP and fails to acknowledge the distinct ways of engaging in health and illness prevention in different socioeconomic groups [Citation125]. Another qualitative study investigating mechanisms in play in the clinical meeting between the patient and the health professional found that health professionals’ presumptions about patients’ resources influenced the communication [Citation126]. Further, Cultural Health Capital, Health Literacy, and QOL may be constructs to explore further in terms of inequality. In particular, there is an urgent call for research that tests the effectiveness of health care interventions to reduce inequality in cancer outcomes. The well-documented socioeconomic inequality in cancer demonstrated in this systematic review, suggests that a focus on inequality should be incorporated into all cancer research to avoid that development of new interventions are designed in a way that they favor patients with a higher SEP, disadvantaging patients with low SEP and thereby increasing the gap. An increased focus on and prioritization of implementation research as an integrated part of research programs testing clinical interventions may be a strategy to ensure equal benefit for all patients regardless of SEP.

Conclusion

This systematic review of population-based Nordic studies gives a comprehensive overview of the literature describing socioeconomic inequality in cancer stage at diagnosis, anticancer treatment and survival. With few exceptions, we found worse outcomes for patients with low SEP across countries, cancer types and outcomes. All cancer sites and outcomes were, however, not represented equally in studies across the countries, and only five cancer sites were examined for all three outcomes (breast, prostate, lung, colorectal and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma). Next steps in reducing socioeconomic inequality in cancer should focus on strategies beyond equal and free access to the health care system, and upscale efforts in intervention and implementation research specifically targeting socioeconomically vulnerable patient groups.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (184.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (54.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data from this study can be accessed upon request with reasonable purpose.

References

- Stringhini S, Guessous I. The shift From heart disease to cancer as the leading cause of death in High-Income countries: a social epidemiology perspective. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(12):877–878.

- Danckert B, Ferlay J, Engholm G NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Survival in the Nordic Countries, et al. 2019. updated 26.03.2019. Version 8.2. https://www-dep.iarc.fr/nordcan/dk/frame.asp

- Lundberg FE, Andersson TM, Lambe M, et al. Trends in cancer survival in the nordic countries 1990-2016: the NORDCAN survival studies. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(11):1266–1274.

- Auvinen A. Social class and Colon cancer survival in Finland. Cancer. 1992;70(2):402–409.

- Brooke HL, Talback M, Martling A, et al. Socioeconomic position and incidence of colorectal cancer in the swedish population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;40:188–195.

- Kravdal O. Social inequalities in cancer survival. Population Studies. 2000;54(1):1–18.

- Mogensen H, Modig K, Tettamanti G, et al. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival among swedish children. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(1):118–124.

- Vehko T, Arffman M, Manderbacka K, et al. Differences in mortality among women with breast cancer by income - a register-based study in Finland. Scand J Public Health. 2016;44(7):630–637.

- Vidarsdottir H, Gunnarsdottir HK, Olafsdottir EJ, et al. Cancer risk by education in Iceland; a census-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(3):385–390.

- Olsen MH, Kjær TK, Dalton SO. Social ulighed i kræft i danmark., Hvidbog København: livet efter kræft, Kraeftens Bekæmpelse 2019.

- Ibfelt EH, Dalton SO, Hogdall C, et al. Do stage of disease, comorbidity or access to treatment explain socioeconomic differences in survival after ovarian cancer? - A cohort study among danish women diagnosed 2005-2010. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(3):353–359.

- Olsen MH, Bøje CR, Kjaer TK, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage at diagnosis of head and neck cancer - a nationwide study from DAHANCA. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):759–766.

- Seidelin UH, Ibfelt E, Andersen I, et al. Does stage of cancer, comorbidity or lifestyle factors explain educational differences in survival after endometrial cancer? A cohort study among danish women diagnosed 2005-2009. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(6):680–685.

- Frederiksen BL, Dalton SO, Osler M, et al. Socioeconomic position, treatment, and survival of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Denmark–a nationwide study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(5):988–995.

- Afshar N, English DR, Milne RL. Factors explaining Socio-Economic inequalities in cancer survival: a systematic review. Cancer Control. 2021;28:10732748211011956.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria 2017. [Available from: http://www.R-project.org/.

- Abdoli G, Bottai M, Sandelin K, et al. Breast cancer diagnosis and mortality by tumor stage and migration background in a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Breast. 2017;31:57–65.

- Berglund A, Holmberg L, Tishelman C, et al. Social inequalities in non-small cell lung cancer management and survival: a population-based study in Central Sweden. Thorax. 2010;65(4):327–333.

- Bergqvist J, Iderberg H, Mesterton J, et al. The effects of clinical and sociodemographic factors on survival, resource use and lead times in patients with high-grade gliomas: a population-based register study. 2018.

- Bower H, Andersson TM, Syriopoulou E, et al. Potential gain in life years for swedish women with breast cancer if stage and survival differences between education groups could be eliminated - Three what-if scenarios. Breast. 2019;45:75–81.

- Brusselaers N, Ljung R, Mattsson F, et al. Education level and survival after oesophageal cancer surgery: a prospective population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003754.

- Brusselaers N, Mattsson F, Lindblad M, et al. Association between education level and prognosis after esophageal cancer surgery: a swedish population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121928.

- Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, et al. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(9):1398–1406.

- Eaker S, Halmin M, Bellocco R, Uppsala/Orebro Breast Cancer Group, et al. Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a national health care system (Sweden). Int J Cancer. 2009;124(1):180–187.

- Eriksson H, Lyth J, Mansson-Brahme E, et al. Low level of education is associated with later stage at diagnosis and reduced survival in cutaneous malignant melanoma: a nationwide population-based study in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(12):2705–2716.

- Frisell A, Lagergren J, Halle M, et al. Socioeconomic status differs between breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy and breast conservation, and affects patient-reported preoperative information. 2019.

- Frisell A, Lagergren J, Halle M, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status on immediate breast reconstruction rate, patient information and involvement in surgical decision-making. BJS Open. 2020;4(2):232–240.

- Gadeyne S, Menvielle G, Kulhanova I, et al. The turn of the gradient? Educational differences in breast cancer mortality in 18 european populations during the 2000s. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(1):33–44.

- Glimelius I, Smedby KE, Albertsson-Lindblad A, et al. Unmarried or less-educated patients with mantle cell lymphoma are less likely to undergo a transplant, leading to lower survival. Blood Adv. 2021;5(6):1638–1647.

- Halmin M, Bellocco R, Lagerlund M, et al. Long-term inequalities in breast cancer survival–a ten year follow-up study of patients managed within a national health care system (Sweden). Acta Oncol. 2008;47(2):216–224.

- He W, Sofie Lindstrom L, Hall P, et al. Cause-specific mortality in women with breast cancer in situ. 2017.

- Hussain SK, Altieri A, Sundquist J, et al. Influence of education level on breast cancer risk and survival in Sweden between 1990 and 2004. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(1):165–169.

- Hussain SK, Lenner P, Sundquist J, et al. Influence of education level on cancer survival in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(1):156–162.

- Lagerlund M, Bellocco R, Karlsson P, et al. Socio-economic factors and breast cancer survival–a population-based cohort study (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(4):419–430.

- Larfors G, Sandin F, Richter J, et al. The impact of socio-economic factors on treatment choice and mortality in chronic myeloid leukaemia. 2017.

- Li X, Sundquist J, Calling S, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and risk of cervical cancer morbidity and mortality: a multilevel analysis from Sweden. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(2):283–289.

- Li X, Sundquist J, Zoller B, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and lung cancer incidence and mortality: a multilevel analysis from Sweden. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(2):256–263.

- Li X, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Neighborhood deprivation and prostate cancer mortality: a multilevel analysis from Sweden. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(2):128–134.

- Linder G, Sandin F, Johansson J, et al. Patient education-level affects treatment allocation and prognosis in esophageal- and gastroesophageal junctional cancer in Sweden. 2018.

- Lissbrant IF, Garmo H, Widmark A, et al. Population-based study on use of chemotherapy in men with castration resistant prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(8):1593–1601.

- Lycken M, Drevin L, Garmo H, et al. The use of palliative medications before death from prostate cancer: swedish population-based study with a comparative overview of European data. 2018.

- Olsson LI, Granstrom F. Socioeconomic inequalities in relative survival of rectal cancer most obvious in stage III. World J Surg. 2014;38(12):3265–3275.

- Olsson LI, Granstrom F, Glimelius B. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(3):347–353.

- Olsson LI, Granstrom F, Pahlman L. Sphincter preservation in rectal cancer is associated with patients’ socioeconomic status. Br J Surg. 2010;97(10):1572–1581.

- Randen M, Helde-Frankling M, Runesdotter S, et al. Treatment decisions and discontinuation of palliative chemotherapy near the end-of-life, in relation to socioeconomic variables. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(6):1062–1066.

- Russell B, Hemelrijck MV, Gardmark T, et al. A mediation analysis to explain socio-economic differences in bladder cancer survival. Cancer Med. 2020;9(20):7477–7487.

- Rutqvist LE, Bern A, Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group Socioeconomic gradients in clinical stage at presentation and survival among breast cancer patients in the Stockholm area 1977-1997. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(6):1433–1439.

- Sachs E, Jackson V, Sartipy U. Household disposable income and long-term survival after pulmonary resections for lung cancer. Thorax. 2020;75(9):764–770.

- Simard JF, Baecklund F, Chang ET, et al. Lifestyle factors, autoimmune disease and family history in prognosis of non-hodgkin lymphoma overall and subtypes. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(11):2659–2666.

- Sjöström O, Silander G, Syk I, et al. Disparities in colorectal cancer between Northern and SouthernSweden - a report from the new RISK North database. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(12):1622–1630.

- Stromberg U, Peterson S, Holmberg E, et al. Cutaneous malignant melanoma show geographic and socioeconomic disparities in stage at diagnosis and excess mortality. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(8):993–1000.

- Tendler S, Holmqvist M, Wagenius G, et al. Educational level, management and outcomes in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): a population-based cohort study. Lung Cancer. 2020;139:111–117.

- Tomic K, Ventimiglia E, Robinson D, et al. Socioeconomic status and diagnosis, treatment, and mortality in men with prostate cancer. Nationwide Population-Based Study. Int J Cancer. 142(12):2478–2484.

- Torbrand C, Wigertz A, Drevin L, et al. Socioeconomic factors and penile cancer risk and mortality; a population-based study. BJU Int. 2017;119(2):254–260.

- Valachis A, Nystrom P, Fredriksson I, et al. Treatment patterns, risk for hospitalization and mortality in older patients with triple negative breast cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(2):212–218.

- Weiderpass E, Oh JK, Algeri S, et al. Socioeconomic status and epithelial ovarian cancer survival in Sweden. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(8):1063–1073.

- Wigertz A, Ahlgren J, Holmqvist M, et al. Adherence and discontinuation of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer patients: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(1):367–373.

- Willen L, Berglund A, Bergstrom S, et al. Educational level and management and outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer. A Nationwide Population-Based Study. 2019;131:40–46.

- Wulaningsih W, Garmo H, Ahlgren J, et al. Determinants of non-adherence to adjuvant endocrine treatment in women with breast cancer: the role of comorbidity. 2018.

- Andersen ZJ, Lassen CF, Clemmensen IH. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1950–1961.

- Arboe B, Halgren Olsen M, Duun-Henriksen AK, et al. Prolonged hospitalization, primary refractory disease, performance status and age are prognostic factors for survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. 2018.

- Arboe B, Olsen MH, Gorlov JS, et al. Treatment intensity and survival in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Denmark: A real-life populationbased study. 2019.

- Birch-Johansen F, Hvilsom G, Kjaer T, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from malignant melanoma in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2043–2049.

- Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Hertzum-Larsen R, et al. Prognostic impact of socioeconomic status on long-term survival of non-localized epithelial ovarian cancer I The extreme study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161(2):458–462.

- Baastrup R, Sorensen M, Hansen J, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the oesophagus, stomach and pancreas in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1962–1977.

- Carlsen K, Hoybye MT, Dalton SO, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from breast cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1996–2002.

- Dalton SO, During M, Ross L, et al. The relation between socioeconomic and demographic factors and tumour stage in women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark, 1983–1999. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(5):653–659.

- Dalton SO, Frederiksen BL, Jacobsen E, et al. Socioeconomic position, stage of lung cancer and time between referral and diagnosis in Denmark, 2001-2008. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(7):1042–1048.

- Dalton SO, Olsen MH, Johansen C, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in cancer survival - changes over time. A population-based study, Denmark, 1987–2013. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):737–744.

- Dalton SO, Ross L, During M, et al. Influence of socioeconomic factors on survival after breast cancer–a nationwide cohort study of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark 1983–1999. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(11):2524–2531.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Engholm G, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from lung cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1989–1995.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Jakobsen E, et al. Socioeconomic position and survival after lung cancer: influence of stage, treatment and comorbidity among danish patients with lung cancer diagnosed in 2004-2010. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):797–804.

- Degett TH, Christensen J, Thomsen LA, et al. Nationwide cohort study of the impact of education, income and social isolation on survival after acute colorectal cancer surgery. 2019.

- Egeberg R, Halkjaer J, Rottmann N, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the Colon and rectum in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1978–1988.

- Engberg H, Steding-Jessen M, Oster I, et al. Regional and socio-economic variation in survival after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in Denmark. Danish Med J. 2020;67(2):A08190438.

- Eriksen KT, Petersen A, Poulsen AH, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the kidney and urinary bladder in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2030–2042.

- Erikson MS, Petersen AC, Andersen KK, et al. National incidence and survival of patients with non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma: a danish population study. Scand J Urol. 2018;52(5–6):364–370.

- Frederiksen BL, Brown PdN, Dalton SO, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in prognostic markers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: analysis of a national clinical database. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(6):910–917.

- Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, Danish Colorectal Cancer Group, et al. Social inequalities in stage at diagnosis of rectal but not in colonic cancer: a nationwide study. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(3):668–673.

- Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, Danish Colorectal Cancer Group, et al. The impact of socioeconomic factors on 30-day mortality following elective colorectal cancer surgery: a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1248–1256.

- Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, et al. Do patient characteristics, disease, or treatment explain social inequality in survival from colorectal cancer? Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(7):1107–1115.

- Ibfelt E, Kjaer SK, Johansen C, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage of cervical cancer in danish women diagnosed 2005 to 2009. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):835–842.

- Ibfelt EH, Kjaer SK, Høgdall C, et al. Socioeconomic position and survival after cervical cancer: influence of cancer stage, comorbidity and smoking among danish women diagnosed between 2005 and 2010. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(9):2489–2495.

- Ibfelt EH, Steding-Jessen M, Dalton SO, et al. Influence of socioeconomic factors and region of residence on cancer stage of malignant melanoma: a danish nationwide population-based study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:799–807.

- Jensen KE, Hannibal CG, Nielsen A, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer of the female genital organs in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2003–2017.

- Kaergaard Starr L, Osler M, Steding-Jessen M, et al. Socioeconomic position and surgery for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: a population-based study in Denmark. Lung Cancer. 2013;79(3):262–269.

- Larsen SB, Brasso K, Christensen J, et al. Socioeconomic position and mortality among patients with prostate cancer: influence of mediating factors. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(4):563–568.

- Larsen SB, Kroman N, Ibfelt EH, et al. Influence of metabolic indicators, smoking, alcohol and socioeconomic position on mortality after breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):780–788.

- Marsa K, Johnsen NF, Bidstrup PE, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from male genital cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2018–2029.

- Mosgaard BJ, Meaidi A, Hogdall C, et al. Risk factors for early death among ovarian cancer patients: a nationwide cohort study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2020;31(3)(pagination):e30.

- Ostgard LSG, Norgaard M, Medeiros BC, et al. Effects of education and income on treatment and outcome in patients With acute myeloid leukemia in a Tax-Supported health care system: a national Population-Based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3678–3687.

- Raedkjaer M, Maretty-Kongstad K, Baad-Hansen T, et al. The association between socioeconomic position and tumour size, grade, stage, and mortality in danish sarcoma patients-A national, observational study from 2000 to 2013. Acta Oncologica. 2020;59(2):127–133.

- Roswall N, Olsen A, Christensen J, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukaemia in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2058–2073.

- Schmidt LS, Nielsen H, Schmiedel S, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from tumours of the Central nervous system in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2050–2057.

- Steding-Jessen M, Birch-Johansen F, Jensen A, et al. Socioeconomic status and non-melanoma skin cancer: a nationwide cohort study of incidence and survival in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34(6):689–695.

- Asli LM, Myklebust TA, Kvaloy SO, et al. Factors influencing access to palliative radiotherapy: a norwegian population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(9):1250–1258.

- Braaten T, Weiderpass E, Lund E. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival: the norwegian women and cancer study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:178.

- Kinge JM, Modalsli JH, Øverland S, et al. Association of household income With life expectancy and Cause-Specific mortality in Norway, 2005-2015. Jama. 2019;321(19):1916–1925.

- Nilssen Y, Strand TE, Fjellbirkeland L, et al. Lung cancer treatment is influenced by income, education, age and place of residence in a country with universal health coverage. 2016.

- Nilssen Y, Strand TE, Fjellbirkeland L, et al. Lung cancer survival in Norway, 1997-2011: from nihilism to optimism. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):275–287.

- Robsahm TE, Tretli S. Weak associations between sociodemographic factors and breast cancer: possible effects of early detection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14(1):7–12.

- Skyrud KD, Bray F, Eriksen MT, et al. Regional variations in cancer survival: impact of tumour stage, socioeconomic status, comorbidity and type of treatment in Norway. 2016.

- Strand BH, Tverdal A, Claussen B, et al. Is birth history the key to highly educated women’s higher breast cancer mortality? A follow-up study of 500,000 women aged 35-54. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(6):1002–1006.

- Trewin CB, Johansson ALV, Hjerkind KV, et al. Stage-specific survival has improved for young breast cancer patients since 2000: but not equally. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;182(2):477–489.

- Finke I, Seppä K, Malila N, et al. Educational inequalities and regional variation in colorectal cancer survival in Finland. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;70:101858.

- Kilpelainen TP, Talala K, Raitanen J, et al. Prostate cancer and socioeconomic status in the finnish randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(10):720–731.

- Kilpelainen TP, Talala K, Taari K, et al. Patients’ education level and treatment modality for prostate cancer in the finnish randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2020;130:204–210.

- Lehto US, Ojanen M, Dyba T, et al. Baseline psychosocial predictors of survival in localised breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(9):1245–1252.

- Lehto US, Ojanen M, Vakeva A, et al. Early quality-of-life and psychological predictors of disease-free time and survival in localized prostate cancer. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(3):677–686.

- Seikkula HA, Kaipia AJ, Ryynanen H, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on stage specific prostate cancer survival and mortality before and after introduction of PSA test in Finland. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(5):891–898.

- Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Saracci R, et al. Reducing social inequalities in cancer: setting priorities for research. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(5):324–326.

- De Prez V, Jolidon V, Willems B, et al. Cervical cancer screening programs and their context-dependent effect on inequalities in screening uptake: a dynamic interplay between public health policy and welfare state redistribution. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):211.

- Lagerlund M, Åkesson A, Zackrisson S. Population-based mammography screening attendance in Sweden 2017-2018: a cross-sectional register study to assess the impact of sociodemographic factors. Breast. 2021;59:16–26.

- Skau B, Deding U, Kaalby L, et al. Odds of incomplete colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening based on socioeconomic status. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;12(1):171.

- Forrest LF, Sowden S, Rubin G, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in stage at diagnosis, and in time intervals on the lung cancer pathway from first symptom to treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2017;72(5):430–436.

- Kogevinas M, Porta M. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival: a review of the evidence. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;(138):177–206.

- Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):5–19.

- Auvinen A, Karjalainen S. Possible explanations for social class differences in cancer patient survival. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;138:377–397.

- Maione P, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter talian lung cancer in the elderly study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6865–6872.

- Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:102.

- Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, EORTC Clinical Groups, et al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):865–871. 2009 Sep 10:

- Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam A-JR, European Union Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 european countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2468–2481.

- Rowley J, Richards N, Carduff E, et al. The impact of poverty and deprivation at the end of life: a critical review. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2021;15:26323524211033873.

- Merrild CH, Andersen RS, Risør MB, et al. Resisting “reason”: A comparative anthropological study of social differences and resistance toward health promotion and illness prevention in Denmark. Med Anthropol Q. 2017;31(2):218–236.

- Dencker A, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Pedersen PV. A qualitative study of mechanisms influencing social inequality in cancer communication. Psycho‐Oncology. 2021;30(11):1965–1972.