Abstract

Background

In-person meeting is considered the gold standard in current communication protocols regarding sensitive information, yet one size may not fit all, and patients increasingly demand or are offered disclosure of bad news by, e.g., telephone. It is unknown how patients’ active preference for communication modality affect psychosocial consequences of receiving potentially bad news.

Aim

To explore psychosocial consequences in patients, who themselves chose to have results of lung cancer workup delivered either in-person or by telephone compared with patients randomly assigned to either delivery in a recently published randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Methods

An observational study prospectively including patients referred for invasive workup for suspected lung cancer stratified in those declining (Patient’s Own Choice, POC group) and those participating in the RCT. On the day of invasive workup and five weeks later, patients completed a validated, nine-dimension, condition-specific questionnaire, Consequences of Screening in Lung Cancer (COS-LC). Primary outcome: difference in change in COS-LC dimensions between POC and RCT groups.

Results

In total, 151 patients were included in the POC group versus 255 in the RCT. Most (70%) in the POC group chose to have results by telephone. Baseline characteristics and diagnostic outcomes were comparable between POC and RCT groups, and in telephone and in-person subgroups too. We observed no statistically significant between-groups differences in any COS-LC score between POC and RCT groups, or between telephone and in-person subgroups in the POC group.

Conclusion

Continually informed patients’ choice between in-person or telephone disclosure of results of lung cancer workup is not associated with differences in psychosocial outcomes. The present article supports further use of a simple model for how to prepare the patient for potential bad news.

Background

Lung cancer is the world leading cause of cancer death [Citation1] with significant social inequality in both tobacco use and cancer survival [Citation2,Citation3]. Worldwide, most patients are diagnosed at Departments of Respiratory Medicine [Citation4,Citation5] during more or less standardised workup packages. The emotional burden for patients undergoing diagnostic workup under suspicion for lung cancer is considerable and associated with shock and uncertainty [Citation6]. Therefore, assessment of patients’ psychosocial response to the diagnostic pathway is an important aspect when developing best practice of communication, including the mode of delivery of the results of diagnostic workup. Disclosure of potentially bad news is a burden for patients, informal caregivers and healthcare professionals leading to ongoing awareness among healthcare professionals on how best to tailor and deliver communication in accord with patients’ preferences, values, and needs [Citation7–9]. For healthcare professionals, disclosure of a cancer diagnosis is considered a difficult task but also regarded a key moment in the patient relationship. Current communication models highlight the in-person meeting as an important condition for empathetic relationship with the patient and/or their family, yet, protocols are emerging on delivery of bad news by telephone or video [Citation10]. Our healthcare system is increasingly oriented towards patient autonomy and shared decision making, including inviting patients and informal caregivers to participate actively in decisions on diagnostic workup and treatment [Citation11,Citation12]. Concerns about this development has been raised that only socially strong patients have the capability to benefit from shared decision making, leading to increased social inequality in health [Citation13].

We have recently published a randomised controlled trial (RCT) on having the workup result of suspected lung cancer delivered by telephone versus in-person meeting in patients, who were informed early and continuously of a possiblecancer diagnosis [Citation14]. Our RCT accommodated a lack of rigorous intervention studies measuring psychosocial consequences in the context of cancer workup [Citation15,Citation16]. We found no differences in psychosocial consequences, but are aware that our results may not be representative since nearly 50% of eligible participants refused randomisation and thus were excluded from the study. The attempt to increase internal validity of an RCTs is often a trade-off with decreased external validity, thus RCTs often provide firm conclusions on a subset of patients [Citation17]. Furthermore, it is likely that different patients have different preferences for mode of communication, which may relate to a multitude of aspects related to e.g., the distance to the hospital, patients’ personal background, and socioeconomic resources [Citation18,Citation19]. Such aspects, which necessarily are not accommodated by a process of randomisation. Parallel to the RCT, we therefore conducted the present non-randomised observational study including all patients who refused randomisation. The observational study built on the theory that psychosocial consequences of facing a possible lung cancer diagnosis may influence patients’ choice of participating in a RCT. For those who refused to participate, we furthermore hypothesised that the psychosocial consequences of a potential lung cancer diagnosis may affect their choice of mode of delivery of the final workup result, and thereafter influence their response to this result. Hence, we assumed that if having the opportunity to choose freely, patients who choose the telephone over an in-person meeting will find themselves appropriately prepared and may not become further psychosocially burdened by this mode of delivery. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore psychosocial consequences in those patients, who actively chose how to have results of lung cancer workup, and comparing this with patients who were randomly assigned to either telephone or in-person meeting in a recently published RCT.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

A single-centre, non-randomised observational design including both patients, who participated and those, who declined to participate in an RCT study conducted within the same time period [Citation14]. As showed in Supplementary File A, study reporting adheres to the STROBE statement [Citation20].

The study was carried out in Department of Respiratory Medicine, Zealand University Hospital Naestved, one of the 14 Danish centres for diagnostic lung cancer package pathways (LCPP).

In Denmark, all patients referred for workup of suspected lung cancer enter a predefined fast track pathway (the LCPP), which aims to ensure rapid and correct assessment and treatment and hopefully improve prognosis and quality of life [Citation21]. The goal is also to provide diagnosis and stage within 28 days, and patients should commence treatment within 35 days, so the LCPP encompasses a standard workup of steps of visitation, diagnostic examinations, assessment and conclusion, and a conversation, where the final diagnosis is disclosed to the patient [Citation21].

Recruitment and participants

Eligible patients in the Participants with Own Choice (POC) group: patients who declined to participate in the RCT due to unwillingness to randomisation, and actively chose to have the final result delivered in-person or by telephone. The RCT group: patients participating in the RCT [Citation14].

Both groups included patients with suspicious lesions in lung, pleura or mediastinum at CT or PET-CT, planned invasive workup, and expected survival >1 month. Patients were excluded if age <18 years, need of in-patient care, or inability to provide verbal and written informed consent. The study was carried out from 2012 to 2016 with last follow-up data entered 31 March 2019.

The intervention

The intervention are described in detail in the RCT study [Citation14]. In short, patients were offered continual information in a mix between telephone calls and in-person meetings tailored to each step of the workup programme. The possibility of malignancy was addressed each time, however, the specific content depended on the clinical likelihood of cancer, suspected stage, differential diagnoses, and patients’ preferences. At step 1 (shortly after referral), patients received a telephone call by an expert in lung cancer workup, and after medical history taking, patients were informed about available imaging results, clinical suspicion, and a plan was made for the next steps was complying with patient’s preferences. Step 2 consisted of additional advanced imaging (e.g., CT, MR, PET-CT) with results and revised clinical suspicion and plan delivered by telephone as default. Step 3 involved the invasive workup in the Bronchoscopy suite. Here, patients met to a physical examination and confirmation of medical history; a sharing of CT, MR, PET-CT images; randomisation (RCT group) to or patient’s decision of (POC group) in-person or telephone disclosure of workup results; and then invasive procedures were performed. Before discharge, the patient was informed about any unexpected findings, and that final results were expected after 3–5 working days. Finally, at step 4, results were disclosed as preferred by the patient.

Generally, physicians strived to communicate in a plain, non-medical language. At the first contacts, typical phrases were: ‘we need to rule out cancer’, ‘cancer is [likely/possible/unlikely]’, ‘if cancer, curative treatment is [likely/unlikely]’, or ‘if biopsies reveal lung cancer, then the most likely treatment is [curative surgery/drugs or radiation that reduce the cancer burden/…]’.

Data collection

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected after inclusion at the day of the invasive workup (baseline) approximately one hour before physical examination and invasive procedures (see Step 3 above), and included the first completion of the Danish version of the questionnaire Consequences of Screening in Lung Cancer (COS-LC) [Citation22] to explore psychosocial status and consequences of going through the workup intervention. Four weeks after delivery of final results (follow-up), participants completed the COS-LC questionnaire again. The COS-LC was sent by email to the participants’ home address with written instructions and a pre-paid return envelope. The research nurse reminded participants who did not respond after two to four weeks, by a telephone call.

Six months after the baseline visit, clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records to obtain baseline data on performance status, lung function, comorbidity, previous cancer, number of medications used, and smoking status. Furthermore, data on the diagnostic outcome and final diagnosis were retrieved.

Content of the questionnaire

The COS-LC is a condition-specific questionnaire measuring psychosocial consequences in lung cancer screening [Citation23]. Until now, no targeted tool has been developed to measure psychosocial consequences of cancer workup, including lung cancer. However, we have previously tested the content validity of COS-LC in a context of lung cancer diagnostic workup where it was found to have high content validity (content relevance and content coverage) [Citation14]. The content validity and psychometric properties of COS-LC are described in detail by Brodersen et al. [Citation22]. The COS-LC part I was applied to measure the psychosocial aspects relevant for patients facing the workup for a potential lung cancer diagnosis. The COS-LC part I comprises four scales: ‘anxiety’ (seven items, score 0–21), ‘behaviour’ (seven items, score 0–21), ‘sleep’ (four items, score 0– 12), and ‘sense of dejection’ (six items, score 0–18) – in total 24 items (). In addition, part I encompasses also five lung cancer specific scales: ‘self-blame’ (five items, score 0–15), ‘focus on airway symptoms’ (two items, score 0–6), ‘introvert’, ‘stigmatization’ (four items, score 0–12), ‘introvert’ (four items, score 0–12), and ‘harms of smoking’ (two items, score 0–6) – in total 17 items. All these 41 items of the nine psychosocial scales have four response categories ranging from 0, 1, 2, or 3. The higher the score of the outcome, the more negative the psychosocial consequences [Citation22].

Statistics

Continuous variables were summarised using mean and standard deviation (SD), and compared using Student’s t test. Categorical variables were summarised using frequencies and percentages and compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared test. Estimates of the means of the various dimensions of COS-LC, corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and a comparison between the development of the dimensions between the POC and the RCT group are done in linear regression models. Missing data were excluded from analyses. No imputation was made. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.4 was used to analyse the data.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Region Zealand, Denmark (no. 12/000660) and was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. For RCT trial protocol, please see clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04315207).

Results

In total, 492 potential participants were approached of whom 151 (31%) participated in the non-randomised study, and 255 (52%) in the RCT, and 86 (17%) were not enrolled or withdrew for different reasons. In the group of participants choosing themselves (POC group) (mean age 67.3 years (SD 9.6); 68 (45%) females), the majority (n = 105; 70%) chose to receive results by telephone (). Supplementary Table 1 shows results of diagnostic workup. In total 116 (77%) were diagnosed with malignancy (predominantly lung cancer) with comparable cancer prevalence between patients choosing in-person meeting versus telephone communication.

Table 1. Baseline data of patients deciding themselves (POC; n = 151) or accepting randomisation (RCT; n = 255) to receive results of lung cancer workup by telephone or in-person.

Change in COS-LC scores from baseline to follow-up (primary outcome)

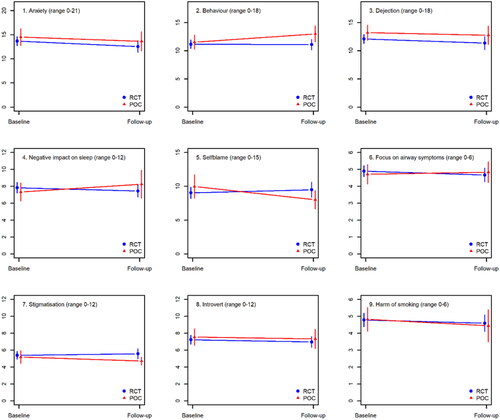

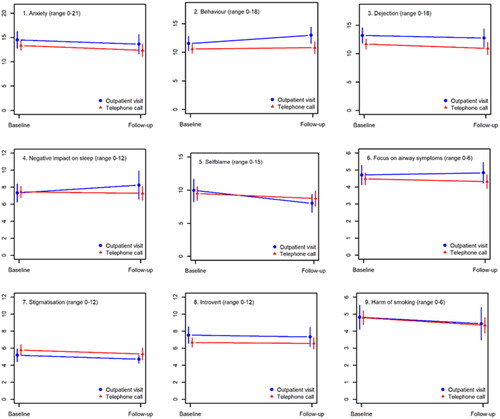

shows that changes in COS-LC scores did not differ significantly between the POC and the RCT population. Similarly, no significant differences in COS-LC changes were observed between patients wanting news by telephone or in-person in the POC group ().

Baseline comparison of patients choosing themselves (POC) and RCT participants

and show that POC and RCT telephone and in-persons subgroups were comparable in all baseline characteristics. Similar results were observed concerning telephone communication subgroups. Baseline COS-LC values were also comparable between these subgroups ().

Table 2. Baseline psychosocial stamina in patients deciding themselves (POC; n = 151) or accepting randomisation (RCT; n = 255) to receive results of lung cancer workup by telephone or in-person.

Table 3. Baseline data of patients deciding themselves (POC; n = 151) or accepting randomisation (RCT; n = 255) to receive results of lung cancer workup by telephone or in-person.

Table 4. Baseline psychosocial stamina in patients deciding themselves (POC; n = 151) or accepting randomisation (RCT; n = 255) to receive results of lung cancer workup by telephone or in-person.

and show identical variables as and but for the overall POC and RCT groups, that were comparable except for a slightly lower drug use in the POC group (). Supplementary Table 2 shows that the prevalence of cancer was similar in the POC and RCT groups.

Discussion

In this study, we did not find any differences between patients participating in an RCT on how to receive the results of lung cancer workup versus patients who chose themselves. Furthermore, we could not demonstrate that patients in the RCT differed in baseline demographics, final diagnoses, or psychosocial stamina from patients choosing communication modality themselves. This suggests that in consenting patient results of cancer workup can be disclosed by telephone without jeopardising their psychosocial condition.

In the current study, most patients chose to receive potentially bad news by telephone rather than as in-person communication. This is in conjunction with findings in both many health-care settings, where telephone conversation is an acceptable communication tool since patients during the last 30 years increasingly perceive the telephone a well-known and safe technology already well-integrated in daily life and health management [Citation24,Citation25]. Until our RCT, little was known on breaking bad news by telephone despite an increasing use of telephone in cancer care [Citation15]. Our study was designed and conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, where telecommunication became an attractive alternative to in-hospital consultations, thus the European Respiratory Society international task force on palliative care recommended that health-care providers should receive systematic training in online communication by telephone or video [Citation26]. Thus, during the pandemic it became no longer a question of whether it was acceptable but on how to best have the difficult conversation by telephone. Telecommunication is not a one-size-fits-all solution, as it may not meet the need of all patients, as illustrated by Kjeldsted et al. [Citation19], who found that having breast cancer, anxiety, or low health literacy were factors associated with a negative experience of telecommunication.

In organising a workup programme for lung cancer, one must weigh the patient’s autonomy and respect for free choice with the known socio-economic inequality in diagnosis, treatment, and mortality [Citation3]. Ultimate autonomy may drive social inequality, well-educated people might end up making better choices and fight for more choices [Citation27]. Patients faced with serious medical decisions may be over- or under-influenced by their physicians, depending on the degree of paternalism or respect for autonomy [Citation27]. Especially when dealing with a potentially vulnerable patient group, it is crucial to know whether the choice of communication promotes or inhibits further treatment success and psychosocial well-being. Sound therapeutic alliances between patients diagnosed with cancer and healthcare professionals can contribute to better adherence of treatment and thereby ultimately potentially reduction in cancer-specific mortality [Citation28–30]. Our results comply with the Shared Decision Making model, a useful guide for healthcare professionals to equip their patients to make well-informed choices, supporting patient empowerment and increased mastery of own health [Citation12,Citation31].

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Strengths are study sample size, novelty, well-defined endpoints, pragmatic design with few exclusion criteria, and use of a validated nine-dimensional questionnaire in a prospective cohort. All patients who received telecommunication had consented to this, either by accepted randomisation or by their own specific choice, and we searched for confounding demographic or disease-related factors driving patients to accept or decline RCT participation. An obvious weakness is that it was a single-centre study on ambulatory patients only in a setting with a unique systematic approach on timing and content of continuously breaking potentially bad news, so the external validity to centres with other information strategies is probably low. Furthermore, we have no qualitative data to understand underlying reasons for patients’ choices, or the apparent psychosocial stability despite disclosure of a malignant diagnosis. COS-LC baseline scores were 6 to 10-fold higher in the present clinical population than in a lung cancer screening cohort suggesting that the COS-LC is a sensitive tool separating patients with low-risk for lung cancer from those with high-risk [Citation14,Citation23]. However, it also raises the hypothesis that being referred in a lung cancer package can have substantial psychosocial consequences maybe also for those patients not diagnosed with lung cancer. Future research most reveal if this hypothesis can be confirmed – and if so, how long such psychosocial consequences last.

Conclusion

The present study supports that disclosure of potentially bad news by telephone is not associated with increased psychosocial consequences compared to in-person meeting in consenting patients to both conversation content and communication modality. Patient-centred care includes communication, and individualised use of alternatives to standard in-person in-hospital visits potentially saves time and costs for both patients, relatives, staff and health-care organisation. Future studies may provide more in-depth knowledge about experiences and reasons why patients choose as they do.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants and staff for their interest and time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data pertaining to this study are included in the manuscript and Supplementary Material. Additional datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Mentis A-F. Social determinants of tobacco use: towards an equity lens approach. Tob Prev Cessat 2017;3:7–8.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Jakobsen E, et al. Socioeconomic position and survival after lung cancer: influence of stage, treatment and comorbidity among danish patients with lung cancer diagnosed in 2004-2010. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):797–804.

- Madsen KR, Høegholm A, Bodtger U. Accuracy and consequences of same-day, invasive lung cancer workup – a retrospective study in patients treated with surgical resection. Eur Clin Respir J. 2016;3:32590.

- Sidhu JS, Salte G, Christiansen IS, et al. Fluoroscopy guided percutaneous biopsy in combination with bronchoscopy and endobronchial ultrasound in the diagnosis of suspicious lung lesions – the triple approach. Eur Clin Respir J. 2020;7(1):1723303.

- Christensen HM, Huniche L. Patient perspectives and experience on the diagnostic pathway of lung cancer: a qualitative study. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120918996.

- Bousquet G, Orri M, Winterman S, et al. Breaking bad news in oncology: a metasynthesis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(22):2437–2443.

- Villalobos M, Siegle A, Hagelskamp L, et al. Communication along milestones in lung cancer patients with advanced disease. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(1–2):41–46.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES – A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302–311.

- Sobczak K. The “CONNECT” protocol: delivering bad news by phone or video call. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:3567–3572.

- Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, et al. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):741–745.

- Steffensen KD. The promise of shared decision making in healthcare. AMS Rev. 2019;9(1–2):105–109.

- Davies M, Elwyn G. Advocating mandatory patient “autonomy” in healthcare: adverse reactions and side effects. Health Care Anal. 2008;16(4):315–328.

- Bodtger U, Marsaa K, Siersma V, et al. Breaking potentially bad news of cancer workup to well-informed patients by telephone versus in-person: a randomised controlled trial on psychosocial consequences. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;30(5):1–11.

- Campbell L, Watkins RM, Teasdale C. Communicating the result of breast biopsy by telephone or in person. Br J Surg. 1997;84(10):1381.

- Paul CL, Clinton-McHarg T, Sanson-Fisher RW, et al. Are we there yet? The state of the evidence base for guidelines on breaking bad news to cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(17):2960–2966.

- Herland K, Akselsen JP, Skjønsberg OH, et al. How representative are clinical study patients with asthma or COPD for a larger “real life” population of patients with obstructive lung disease? Respir Med. 2005;99(1):11–19.

- McElroy JA, Proulx CM, Johnson L, et al. Breaking bad news of a breast cancer diagnosis over the telephone: an emerging trend. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):943–950.

- Kjeldsted E, Lindblad KV, Bødtcher H, et al. A population-based survey of patients’ experiences with teleconsultations in cancer care in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(10):1352–1360.

- Elm E, von Altman DG, Egger M, STROBE Initiative, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Pakkeforløb for lungekraeft. 2018. Available from: pakkeforløb-for-lungekraeft-2018.ashx (sst.dk)

- Brodersen J, Thorsen H, Kreiner S. Consequences of screening in lung cancer: development and dimensionality of a questionnaire. Value Health. 2010;13(5):601–612.

- Rasmussen JF, Siersma V, Pedersen JH, et al. Psychosocial consequences in the Danish randomised controlled lung cancer screening trial (DLCST). Lung Cancer. 2015;87(1):65–72.

- McBride CM, Rimer BK. Using the telephone to improve health behavior and health service delivery. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37(1):3–18.

- Alexander KE, Ogle T, Hoberg H, et al. Patient preferences for using technology in communication about symptoms post hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):11.

- Janssen DJA, Ekström M, Currow DC, et al. COVID-19: guidance on palliative care from a European respiratory society international task force. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(3):2002583.

- Quill TE, Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(9):763–769.

- Trevino KM, Fasciano K, Prigerson HG. Patient-oncologist alliance, psychosocial well-being, and treatment adherence among young adults with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(13):1683–1689.

- Kissane D. Beyond the psychotherapy and survival debate: the challenge of social disparity, depression and treatment adherence in psychosocial cancer care. Psychooncology. 2009;18(1):1–5.

- Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186458.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923–1939.