Abstract

Background

Oesophago-gastric cancers have had sharply different and changing incidence patterns depending on subsite and histology, but incidence data for the last few years are missing. We aimed to provide updated incidence trends of oesophago-gastric tumours by subsite and histology in Sweden.

Material and Methods

The Swedish Cancer Registry provided data for 74,303 patients with oesophago-gastric cancer aged ≥50 years in 1970–2020. The focus was on the last available 6-year period, i.e., from 2015 until 2020 inclusive. We calculated yearly age-standardized and sex-specific incidence rates per 100,000 person-years, with the age distribution (in 5-year age groups) of the Swedish population in year 2000 as reference.

Results

For oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, the incidence continued to decrease between 2015 and 2020 (from 6.46 to 5.53/100,000 person-years in men, and from 4.26 to 3.78/100,000 person-years in women). For oesophageal adenocarcinoma, the earlier increasing incidence rates rather slightly decreased in men between 2015 and 2020 (from 12.39 to 11.70/100,000 person-years) and increased marginally in women (from 2.49 to 2.85/100,000 person-years). The incidence rates of cardia adenocarcinoma were stable between 2015 and 2020 (from 9.83 to 10.13/100,000 person-years in men, and from 2.21 to 2.41/100,000 person-years in women). For gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma, the incidence rates continued to decrease between 2015 and 2020 (from 14.67 to 13.29/100,000 person-years in men, and from 9.37 to 8.14/100,000 person-years in women). There were no major age-group differences in recent incidence trends.

Conclusion

The 6-year period from 2015 to 2020 inclusive has witnessed stabilising incidence rates of oesophageal and cardia adenocarcinoma in Sweden, whereas the incidence rates of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma have continued to decrease.

Introduction

Oesophago-gastric cancers are among the most common and deadly tumours globally [Citation1,Citation2]. The incidence rates have changed greatly during the last few decades, with divergent trends depending on histology and subsite. For oesophageal cancer, the histological type squamous cell carcinoma dominates globally [Citation3], but its incidence has decreased in western populations [Citation4–6]. Meanwhile, the incidence of adenocarcinoma, the other main histological type of oesophageal cancer, has increased rapidly in most western countries [Citation4–6]. As a result, adenocarcinoma has become the most common histological type of oesophageal cancer in several western countries, including Sweden [Citation7–9]. For gastric cancer, adenocarcinoma is the predominant histological type (>95%), but there is evidence of diverging incidence trends with regards to the topographical subsites cardia (proximal stomach) and non-cardia (distal stomach) [Citation1,Citation10]. The incidence of cardia adenocarcinoma has namely increased during the last few decades, similar to that of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, whereas the incidence of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma has steadily decreased [Citation11–13]. These differences in time trends may be due to changes in the prevalence of the main risk factors, i.e., tobacco smoking and alcohol overconsumption for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obesity for oesophageal and cardia adenocarcinoma, and Helicobacter pylori-infection for non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma [Citation9,Citation14]. In addition, sex and age influence the incidence of all these tumours [Citation15]. There is a great need to know the recent trends in the incidence of these tumours, but delays in national cancer recording reduce the availability of incidence data, which are lacking for the last few years [Citation4–6,Citation15,Citation16]. Previous studies on the incidence of these tumours in Sweden provided data until 2014, but not later [Citation8,Citation10]. However, the Swedish Cancer Registry now has complete and accurate national incidence data for the year 2020, enabling us to achieve the aim of providing national incidence trends of oesophago-gastric cancer in Sweden for a recent period. We hypothesised that the incidence trends seen during the last few decades have continued during the last few years.

Material and methods

Design

This population-based cohort study included all Swedish residents with oesophago-gastric cancer at 50 years and older (there are few oesophago-gastric cancer patients diagnosed below this age) between 1970 and 2020. The focus was on the last 6 years, i.e., 2015–2020, which were not included in our previous incidence studies from Sweden [Citation8,Citation10]. The incidence of four oesophago-gastric cancer subtypes was analysed separately: 1) Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, 2) oesophageal adenocarcinoma, 3) cardia adenocarcinoma, and 4) non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma. Data were retrieved from the national Swedish Cancer Registry, which has over 98% nationwide completeness in the recording of oesophago-gastric cancer and 100% completeness regarding histological confirmation of these tumours according to validation studies examining the period 1995–1997 for oesophageal cancer and 1989–1994 for gastric cancer [Citation17,Citation18]. The Cancer Registry provided age- and sex-specific data and year of diagnosis. The seventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-7) was used to identify site codes representing oesophageal cancer (150), cardia cancer (151.1), and non-cardia gastric cancer (151.0, 151.8, 151.9). The Swedish Cancer Registry uses ICD-7 codes for all tumours for uniformity reasons. Histology codes in the WHO/HS/CANC/24.1 defined squamous cell carcinoma (146) and adenocarcinoma (096). Each malignant tumour is reported to the Swedish Cancer Registry also if there are multiple primaries. The Cancer Registry includes autopsy-proven tumours, but does not include tumours only recorded in a death certificate [Citation19]. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (number 2022-05431-02). We used the STROBE checklist for cohort studies for the reporting.

Statistical analysis

The sex-specific annual age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 person-years were calculated using the direct method, with the age distribution (in 5-year age groups) of the Swedish population in the year 2000 as reference. Besides stratifying by sex (male and female), the age-standardized results were also stratified by two age groups (50–69 and ≥70 years). Log-linear joinpoint regression was used to identify change points in incidence rates and to estimate annual percentage changes with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in the time segments before and after any change points, assuming that the rates changed at a constant percentage per year on a log scale in each time segment. A maximum of 4 change points and a minimum of 9 observations between 2 joinpoints were allowed. All data management and statistical analyses were conducted by an experienced biostatistician (FM) who followed a detailed and pre-defined study protocol. The analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), except for the joinpoint regression which was performed using the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.9.1.0 (Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute, United States).

Results

Patients

The study included 74,303 patients with oesophago-gastric cancer diagnosed at the age of 50 years or older (). Of these, 10,196 had oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (66% men), 6,555 had oesophageal adenocarcinoma (81% men), 8,587 had cardia adenocarcinoma (77% men), and 48,965 had a diagnosis of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma (60% men).

Table 1. Distribution of 74,303 patients with oesophago-gastric cancer diagnosis between 1970–2020 in Sweden.

Incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma

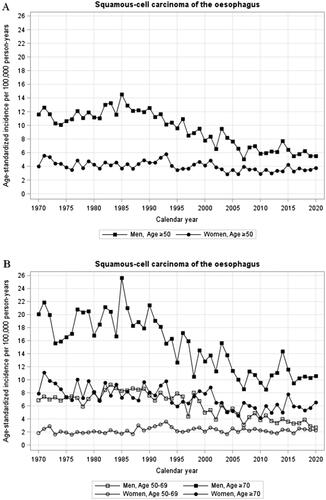

Men: For oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, the age-standardized incidence rate in men decreased strongly between 1985 and 2007, from when the incidence decreased only moderately without any joinpoint (annual percentage change −1.0, 95% CI −2.3 to 0.3) (, ). During the last 6 years, the incidence continued to decrease moderately (from 6.46 to 5.53/100,000 person-years between 2015 and 2020). There were no clear differences in incidence trends between age groups (, ).

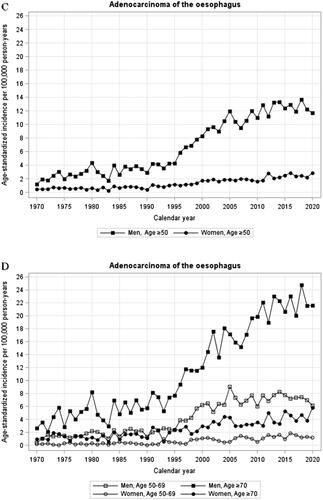

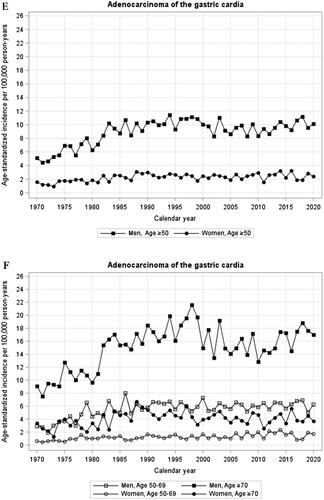

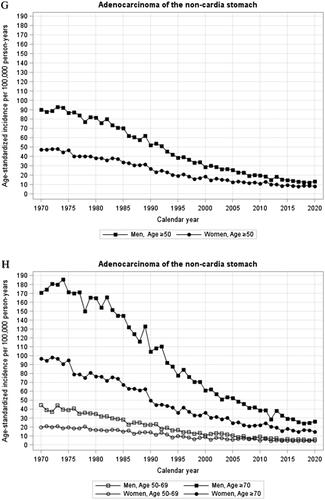

Figure 1. (A-H) Annual age-standardized incidence rates by sex and age of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (A,B), oesophageal adenocarcinoma (C,D), cardia adenocarcinoma (E,F), and gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (G,H) in Sweden, 1970–2020.

Table 2. Annual percentage changes (APC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in age-standardized incidence rates of oesophago-gastric cancer.

Women: The incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma slightly decreased in women throughout the study period without joinpoints (annual percentage change −0.6%, 95% CI −0.9 to −0.4) (, ). Between 2015 and 2020, the incidence decreased slightly from 4.26 to 3.78/100,000 person-years. There were no major differences in incidence trends over time comparing younger and older women (, ).

Incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma

Men: The incidence rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma increased strongly in men between 1993 and 2001, and slightly from 2003 onwards (), with joinpoints identified in 1993 and 2001 (). However, the incidence rather slightly decreased between 2015 and 2020 (from 12.39 to 11.70/100,000 person-years) (, ). Among men aged 50–69 years, the incidence decreased from 7.74/100,000 person-years in 2015 to 6.12/100,000 person-years in 2020, while the corresponding incidence rates in men older than 70 years were unchanged between 2015 and 2020 (, ).

Women: The incidence rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma increased in women during the entire study period without joinpoints (annual incidence change 3.9%, 95% CI 3.4 to 4.5%) (, ). The incidence increased only marginally between 2015 and 2020 (from 2.49 to 2.85/100,000 person-years). The number of cases in the age group 50–69 years was too few to analyse, and the incidence in women older than 70 years followed the same trend as for all women (, ).

Incidence of cardia adenocarcinoma

Men: Following an increase in the incidence of cardia adenocarcinoma in men between 1970 and 1986 (, ), the incidence has been stable from 1986 onwards without joinpoints (annual incidence change −0.1%, 95% CI −0.5 to −0.2). The incidence was similar in 2015 (9.83/100,000 person-years) and 2020 (10.13/100,000 person-years). There were no major differences in incidence trends over time comparing younger and older men (, ).

Women: The age-standardized incidence rate of cardia adenocarcinoma in women increased from 1970 until 1988 after which it has been stable, including the last 6 years (, ).

Incidence of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma

Men: The incidence of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma decreased during the entire study period in men, particularly after a joinpoint in 1982 (annual percentage change −4.9%, 95% CI −5.1 to −4.8) (, ). During the last 6 years, the incidence decreased moderately (from 14.67 in 2015 to 13.29/100,000 person-years in 2020) without joinpoints. There were no major differences comparing the age groups ( and ).

Women: The incidence trends of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma in women were similar to that seen in men, the only major difference being that the stronger decrease started a few years later (in 1986) and flattened slightly from 1995 onwards (annual percentage change −3.7%, 95% CI −4.1 to −3.4) (, ). The incidence decreased moderately without joinpoint between 2015 and 2020 (from 9.37 to 8.14/100,000 person-years). There were no major differences between age groups ( and ).

Discussion

This study indicates that during 2015–2020 the incidence rates of oesophageal and cardia adenocarcinoma have stabilised in Sweden, whereas the incidence rates of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma have continued to decrease moderately.

Among strengths of the study is the utilisation of highly complete, accurate, and updated information on national incidence rates of the studied tumours in Sweden. Among limitations is that the joinpoint regression analysis is a relatively inexact instrument to assess shifts in incidence trends, and the specific years in which we describe trend shifts should be interpreted cautiously. Yet, joinpoint regression does allow an objective assessment of incidence changes over time. The statistical power was limited and variations could by chance influence the incidence estimates, making the assessment of changes in time trends less robust. Tumour misclassification is uncommon when separating the histological types adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma, but is a known problem for cardia adenocarcinoma, which can be confused with both oesophageal and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma [Citation17,Citation18]. However, such misclassification should not much influence changes the incidence trends studied here. The Covid-19 pandemic might have contributed to diagnostic delays in the year 2020, but due to the aggressiveness and alarming symptoms of oesophageal and gastric cancer, this should not have been a major concern for the present study. Finally, the results may not be generalisable to other countries. However, similar trends may likely be seen in other western countries with similar trends in the prevalence of the main etiologic factors.

The Swedish incidence rates of these tumours are similar to most Nordic countries, but lower than in most other countries in Europe and globally. The decreasing incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, seen in most of the western world, has largely been attributed to reduced tobacco smoking and alcohol abuse [Citation20], while in high-incidence areas (e.g., China), the decline may rather be driven by improvements in food preservation [Citation1,Citation21]. The present study indicates that the decrease might have slowed down slightly during the last few years in Sweden, which could be due to a more stable prevalence of the main risk factors. But this hypothesis remains to be established in future research.

The rapidly increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and cardia should not be explained by changes in diagnostic assessments, because the increase has continued during long periods without any major changes in diagnostic tools. The increase has been paralleled by an increasing prevalence of the risk factors gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and obesity, combined with a decreasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, which decreases the risk of these tumours [Citation9,Citation14]. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori has decreased also in Sweden, and been estimated to currently be as low as around 11% [Citation22]. The stabilisation in incidence rates seen during the last 6 years in Sweden could potentially be due to unchanged prevalence rates of these aetiological factors. This hypothesis needs to be confirmed in other studies. Only time will tell whether this is a temporary observation or the start of a plateau or even a peak.

The declining incidence of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma has mainly been attributed to the reduced prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and advances in food preservation [Citation11,Citation21,Citation23]. The decrease was slightly less marked during the last few years in Sweden, which might potentially be due to a more stable prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. This hypothesis warrants research.

Taken together, the stabilising incidence of oesophageal and cardia adenocarcinoma and the continued decrease in the incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma in Sweden are encouraging and provide hope for an overall decreasing incidence of these devastating tumours in the future.

In conclusion, this nationwide Swedish study suggests that the age-standardized incidence rates of oesophageal and cardia adenocarcinoma have stabilised during the period 2015–2020 compared to earlier years, which slightly differ from the hypothesis, and that the recent incidence rates of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma as hypothesised have continued to decrease although at a possibly slower rate. If these trends remain over time and are found also in other countries, the overall burden of oesophago-gastric cancer may decrease.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at the governmental agency Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author JL on request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33.

- Collaborators GBDOC The global, regional, and national burden of oesophageal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(6):582–597.

- Lin Y, Wang HL, Fang K, et al. International trends in esophageal cancer incidence rates by histological subtype (1990-2012) and prediction of the rates to 2030. Esophagus. 2022;19(4):560–568.

- Rumgay H, Arnold M, Laversanne M, et al. International trends in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma incidence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(5):1072–1076.

- Huang J, Koulaouzidis A, Marlicz W, et al. Global burden, risk factors, and trends of esophageal cancer: an analysis of cancer registries from 48 countries. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(1):141.

- Fan J, Liu Z, Mao X, et al. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer from 1990 to 2017. Cancer Med. 2020;9(18):6875–6887.

- Xie SH, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Incidence trends in oesophageal cancer by histological type: an updated analysis in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;47:114–117.

- Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2383–2396.

- Lagergren F, Xie SH, Mattsson F, et al. Updated incidence trends in cardia and non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(9):1173–1178.

- Wong MCS, Huang J, Chan PSF, et al. Global incidence and mortality of gastric cancer, 1980-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2118457.

- Arnold M, Park JY, Camargo MC, et al. Is gastric cancer becoming a rare disease? A global assessment of predicted incidence trends to 2035. Gut. 2020;69(5):823–829.

- Lin Y, Zheng Y, Wang HL, et al. Global patterns and trends in gastric cancer incidence rates (1988-2012) and predictions to 2030. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(1):116–127 e8.

- Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, et al. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396(10251):635–648.

- Wang S, Zheng R, Arnold M, et al. Global and national trends in the age-specific sex ratio of esophageal cancer and gastric cancer by subtype. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(9):1447–1461.

- Zhang T, Chen H, Zhang Y, et al. Global changing trends in incidence and mortality of gastric cancer by age and sex, 1990-2019: findings from global burden of disease study. J Cancer. 2021;12(22):6695–6705.

- Lindblad M, Ye W, Lindgren A, et al. Disparities in the classification of esophageal and cardia adenocarcinomas and their influence on reported incidence rates. Ann Surg. 2006;243(4):479–485.

- Ekstrom AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, et al. Evaluating gastric cancer misclassification: a potential explanation for the rise in cardia cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(9):786–790.

- Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, et al. The completeness of the swedish cancer register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):27–33.

- Prabhu A, Obi KO, Rubenstein JH. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(6):822–827.

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Camargo MC, et al. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: a population-based modelling study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101404.

- Agreus L, Hellstrom PM, Talley NJ, et al. Towards a healthy stomach? Helicobacter pylori prevalence has dramatically decreased over 23 years in adults in a swedish community. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4(5):686–696.

- Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–429.