Abstract

Background

The promise of prolonged survival after psychosocial interventions has long been studied, but not convincingly demonstrated. This study aims to investigate whether a psychosocial group intervention improved long-term survival in women with early-stage breast cancer and investigate differences in baseline characteristics and survival between study participants and non-participants.

Methods

A total of 201 patients were randomized to two six-hour psychoeducation sessions and eight weekly sessions of group psychotherapy or care as usual. Additionally, 151 eligible patients declined to participate. Eligible patients were diagnosed and treated at Herlev Hospital, Denmark, and followed for vital status up to 18 years after their primary surgical treatment. Cox’s proportional hazard regressions were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for survival.

Results

The intervention did not significantly improve survival in the intervention group compared with the control group (HR, 0.68; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.41–1.14). Participants and non-participants differed significantly in age, cancer stage, adjuvant chemotherapy, and crude survival. When adjusted, no significant survival difference between participants and non-participants remained (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.53–1.11).

Conclusions

We could not show improved long-term survival after the psychosocial intervention. Participants survived longer than nonparticipants, but clinical and demographic characteristics, rather than study participation, seem accountable for this difference.

Background

For decades, it has been assumed that psychological factors such as stress [Citation1], personality [Citation2–5], or depression [Citation1] increased cancer initiation and progression. These ideas were extended to include the hypothesis that psychological states and interventions had the potential to prolong life in cancer survivors [Citation6]. This notion of a mind-body survival connection for especially breast cancer patients was advocated by Spiegel et al. [Citation7], who were among the first to report a survival advantage for breast cancer patients after a psychosocial intervention.

Overall, results of published trials on survival among breast cancer patients have been conflicting, with several negative findings from trials including metastatic [Citation8–12] and early-stage [Citation13] breast cancer patients, and a few positive findings in trials of metastatic [Citation7] and early-stage cancer [Citation14,Citation15] (Supplemental Table 1 lists study details). These studies were all based on group-delivered interventions with a duration between 15 and 39 therapy hours. The interventions included psychological approaches and strategies to reduce distress, improve quality of life and health behaviors, facilitate cancer treatment compliance and medical follow-up [Citation15,Citation16], cognitive-existential group therapy [Citation13,Citation17], and group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention and relaxation training [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19]. Many studies, however, have either not had sufficient statistical power or length of follow-up to evaluate survival effects [Citation16,Citation20,Citation21].

Following these reports, two meta-analyses synthesized the findings regarding survival in early-stage breast cancer patients after psychosocial interventions [Citation22,Citation23], with conflicting findings. The most recent meta-analysis found a statistically significant effect on survival in early-stage cancer [Citation23], while the previous publication reported a statistically non-significant survival effect [Citation22]. Although pathways and mechanisms of the mind-body connection applied to cancer survival have yet to be conclusively established [Citation1,Citation6], the underlying assumption is that negative psychosocial states harm body functions and cancer resistance mediated through biological mechanisms [Citation1] and health behavior [Citation24].

Whether or not psychosocial interventions are effective, may also depend on the population targeted and included in trials. As psychosocial interventions may appeal only to a selected sub-population of patients with greater psychological or social resources [Citation25] studies published so far [Citation26–28] may suffer from a general problem of generalizability. Further, it has been argued that psychological interventions have the greatest impact on psychosocial outcomes in those patients distressed at the time of inclusion [Citation16,Citation29]. Whether those most distressed also have the greatest survival advantage is still unsure.

Here we report the effect of a combined psychoeducational and cognitive–supportive group intervention on overall long-term survival in early-stage breast cancer patients up to 18 years after primary surgery, using register-based data on vital status free from information bias. Further, to address the issue of generalizability to the overall population, we investigate differences in baseline characteristics and survival for participants and non-participants (decliners).

Material and methods

The original trial was a two-arm randomized clinical trial (RCT), conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, registered at clinicaltrail.gov (NCT01108224), and approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Copenhagen County (KA 04005). The purpose of the trial was to test the effectiveness of a psychosocial group intervention to improve psychological distress and 4-year survival.

Patients

Eligible patients were diagnosed and treated at Herlev Hospital (University Hospital of Copenhagen, Denmark) for primary breast cancer stage I to IIIA, between 18 and 70 years old, and fluent in Danish. Patients were ineligible if they had previously been diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm (except for non-melanoma skin cancer and cervical dysplasia), or had any known psychiatric diagnosis, dementia, or neuropsychological deficits.

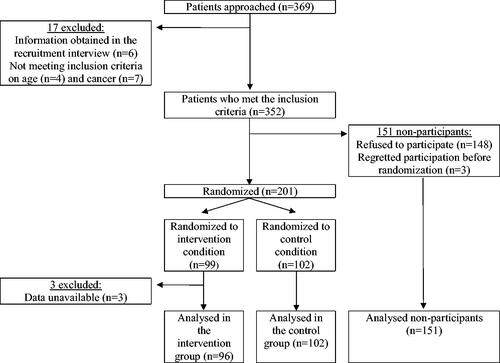

Between 1 October 2003 and 1 December 2005, physicians approached a total of 369 patients, excluding 17 patients based on inclusion criteria (). A total of 201/352 patients (57%) provided informed consent and were randomized to the intervention or control group, using a combination of sealed envelopes and an online database, thus blinding study personnel to the randomization sequence. The remaining 151 patients (43%) declined to participate in the RCT, but their clinical data were available for analysis. Three patients from the intervention group were excluded from the present analyses as data were unavailable. Thus, the final population for the present study consisted of 96 patients in the intervention group, 102 in the control group and 151 nonparticipating patients.

Baseline clinical and outcome measures

Clinical data on surgery (mastectomy, lumpectomy, other), cancer stage (I, II, III, missing), date of primary cancer surgery, tumor size (1–10, 10.1–20, 20.1–40; ≥40.1 mm), lymph nodes status (positive, negative), estrogen receptor status (positive, negative), adjuvant chemotherapy (yes, no), and adjuvant anti-hormonal therapy (yes, no) were retrieved from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) clinical database [Citation30]. The DBCG database contains data from the departments of pathology, surgery, and oncology concerning diagnostic procedures, surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy, and clinical follow-up, recurrence, contralateral breast cancer and other malignant disease for up to 10 years [Citation30]. Through linkage via the unique 10-digit personal identifier, assigned to all persons living in Denmark since 1968, date of birth and vital status on 20 January, 2021 were retrieved from the Danish Civil Registration System [Citation31].

Group intervention

This intervention consisted of an adapted Cognitive-existential Group Therapy with two parts (details reported in Boesen et al. 2011 [Citation21]): (A) two days with 6 h of lectures about treatment, social rights, diets, strategies from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, sexual problems, and physical training, given by breast cancer specialists within medicine and nursing; (B) eight sessions of 2.5 h group therapy to share cancer stories, followed by a half hour informal gathering with refreshments. These sessions were held in groups of eight women and led by a clinical psychologist trained to integrate cognitive therapy in the group work; further, a specialized nurse was available during the lessons to answer questions about disease and treatment. The primary aim of the intervention was to improve the psychological and physical well-being, disease coping, social relations and health behavior, and the secondary outcome was to improve survival.

Statistical analyses

Patients were followed from the date of primary surgery until the date of death, emigration, disappearance, or end of follow-up (January 20th, 2021), whichever came first. Descriptive statistics were computed for baseline characteristics (number and frequency) and group differences were compared by chi-squared test. Mortality patterns for the patient groups were compared by Kaplan-Meier curves. A Cox’s proportional hazards (PH) regression was performed to investigate the survival differences between the intervention group, the control group, and non-participants using estimates of hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and Schoenfeld residual were inspected. A sensitivity analysis with complete cases only was performed adjusting for strong prognostic factors: Age, lymph node status, tumor size, and estrogen receptor status. We planned to stratify participants according to the effect on self-reported depression at 1 year follow-up (significant change vs. not) but were unable to perform this analysis due to limited power. Further Cox’s PH regressions were performed to investigate survival of participants (intervention and control group combined) compared with non-participants: First, a crude analysis including the whole population, second a sensitivity analysis with complete cases, adjusted for prognostic factors. We performed a post hoc power analysis to determine minimum detectable HRs given our sample size and design (Supplemental Material 1). All analyses were performed in R version 1.3.959.

Results

Of 349 patients included, 124 had died (36%), 2 had emigrated (0.6%), and 223 (64%) were still alive on 20 January 2021. Of those who died, 25/96 (26%) were from the intervention group, 37/102 (36%) were from the control group, and 62/151 (41%) were non-participants (). At baseline, the randomized groups only differed in tumor size, as a greater proportion of the intervention group had small tumors compared to the control group (). Non-participants were statistically significantly older, more likely to have lower cancer stage, and less like to have received adjuvant chemotherapy than participants ().

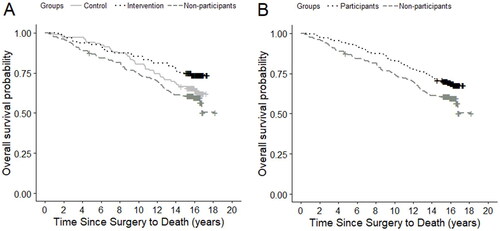

Figure 2. (A,B) Kapla–Meier survival curves of 18-year mortality patterns in the randomized intervention study of psychoeducation and group psychotherapy, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003–2006. (A) Control group, intervention group, and non-participants. (B) Participants (intervention and control group combined) and non-participants.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 349 women with breast cancer included in a randomized intervention study of psychoeducation and group psychotherapy, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003–2006.

Although the groups’ survival curves do diverge in Kaplan-Meier plots (), no statistically significant differences in survival were found when comparing the intervention group (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.41–1.14) nor the non-participants (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.82–1.85) with the control group (). We observed the longest survival, as expected, in the intervention group and progressively decreased survival in the control group and non-participants. The sensitivity analysis adjusted for prognostic factors did not change the conclusion (). Furthermore, no statistically significant difference in survival was found between all participants (intervention and control group) (adjusted HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.51–1.10) and non-participants ().

Table 2. Overall survival analyses by randomization group from the randomized intervention study of psychoeducation and group psychotherapy, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003–2006.

Table 3. Overall survival analyses by participation status from the randomized intervention study of psychoeducation and group psychotherapy, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003–2006.

Discussion

In this long-term follow-up analysis of a randomized controlled psychosocial intervention trial, we observed no statistically significant survival effect up to 18 years after the intervention was concluded. Neither did we observe that participants in the RCT lived statistically significantly longer than non-participants. The HR of 0.68 with a 95% CI ranging from 0.41 to 1.14 for the intervention group compared with the control group, indicates lack of power, but does not rule out that an effect could be seen with a larger sample size. Indeed, a lot of the plausible effects within the CI would be clinically meaningful.

Our findings are in line with Kissane et al.’s findings of no significantly improved survival five years after an intervention in the same patient population, although with HRs in opposing directions [Citation13]. In contrast, Andersen et al. and Stagl et al. found a significant survival effect 12 months and 11 years after the interventions, respectively [Citation14,Citation15]. One may wonder if differences in characteristics of the intervention provided contributed to explaining the observed differences between published studies in this field. However, not many general differences between the interventions are apparent; All were group-delivered and consisted of weekly sessions to improve psychological well-being [Citation13–15], while two studies supplemented the intervention with relaxation training [Citation13,Citation14] and one other intervention, in addition to the present, included strategies to improve quality of life, health behaviors and treatment compliance [Citation15]. Interventions ranged from 15 to 39 h in total, with the shortest and longest interventions given in the two studies with statistically significant survival effects. Indeed, no intervention-characteristics alone were identified as potential moderators of the intervention effects in a previous meta-analysis, though cognitive-behavioral interventions may be particularly beneficial in patients with early stage cancers [Citation23]. The same meta-analysis pointed to population characteristics as potential moderators, with greater survival effects in populations with a mean age below 50 or a larger proportion of unmarried patients [Citation23]. In our population less than 50% patients were below age 50 and most were married or cohabiting [Citation21], potentially limiting the intervention effect.

A hypothetically more important moderator, however, could be the intervention effect on psychological outcomes. Spiegel et al. [Citation7] who originally reported improved survival after a psychosocial intervention in breast cancer patients, also identified an effect on the psychological outcomes [Citation7,Citation32], which was not found in the present trial [Citation21]. If effects of psychosocial interventions on survival are mediated by improvement in psychological outcomes, we would not observe a survival effect in this study. Previous trials reported beneficial effects on psychological outcomes, such as reduced anxiety [Citation13,Citation16], or depression [Citation18,Citation19]. If, however, psychosocial interventions could affect behaviors related to health, such as lifestyle or health care seeking, as seen in significantly greater knowledge about cancer and its treatment in one trial [Citation13,Citation17], such changes may affect survival [Citation33,Citation34] in the absence of effects on psychological well-being. We collected self-reported data before randomization and at 1, 6, and 12 months after the intervention, and thereby had data available in the present trial on effects on depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up. However, our sample size was too small to stratify the survival analysis based on this information, and we did not have data on health behaviors. Thus, we are not able to shed light on one potential mechanism of psychosocial intervention effects on survival, namely that those with a reduction in depressive symptoms would live longer. Furthermore, we did not have data to assess the effects on lifestyle, health behaviors or general health. As a result, we are unable to assess and distinguish between these different pathways that potentially would be the mechanism explaining the hypothesized effect. However, if psychosocial interventions indeed confer greater benefit among the subgroup of those most distressed [Citation16,Citation29], adopting an approach of individualized rehabilitation may be beneficial (e.g. [Citation35,Citation36]).

Of the women invited into the present trial, 57% chose to participate. We included non-participants in our analyses, which enabled us to assess the representativeness of participants. Non-participants were statistically significantly older, had lower cancer stage, and less often received adjuvant chemotherapy. This emphasizes the importance of including non-participants in the analysis to investigate generalizability of the findings. There was, however, no statistically significant difference between participants and non-participants’ survival, when adjusting for age and clinical characteristics. This finding might be influenced by the limited available covariates, as demographics and health behavior variables were inaccessible for non-participants. The reasons why some women declined to participate were investigated among 64 women, who most frequently cited practical circumstances, time constraints and dislike of group therapy [Citation21]. Spiegel et al. [Citation12] reported a perceived change in attitude toward and willingness to receive psychosocial support when comparing recruitment into their two studies separated by almost two decades. Although none of the previous trials have accounted for generalizability by including non-participants in the analysis, there is reason to believe that participants likely were not representative of the overall patient population, as it is well-established that some patients have a higher tendency to decline participation in intervention studies testing physical training, information and coping skills training [Citation27], mindfulness-based stress reduction [Citation37], or psychosocial group interventions [Citation38,Citation39]. Although no survival differences were found between participants and non-participants in this trial, the differences in group characteristics and preference-based reasons for nonparticipation should prompt future research to include analyses of this aspect of generalizability.

Our study had certain advantages including the use of virtually complete follow-up data from the registration of vital status in the Danish Civil Registration System [Citation31]. We had up to 18 years of follow-up, ensuring more events compared to previous studies in early-stage breast cancer patients [Citation13–15]. Even though we can present the longest follow-up to date, we cannot rule out that long-term effects could surface after this period of time. Our population was recruited through systematic invitation of patients at Herlev Hospital (Denmark), in a tax based, free for all health system that promotes equitable access to care and should therefore increase the generalizability of our findings.

Furthermore, the register-based data on tumor, treatment, and vital status were recorded independently of the study, which reduces the risk of bias and differential, dependent misclassification [Citation40]. Generally, Danish databases contain high-quality data suitable for epidemiological research [Citation41]. However, among the weaknesses of the study was the unavailability of information on adjuvant radiotherapy as well as a substantial proportion missingness for data on receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy and anti-hormone therapy, limiting our ability to control for treatment factors. This did not affect the primary unadjusted analysis but would have provided valuable information in our sensitivity analysis. Instead, we included disease related variables (tumor size, receptor, and lymph node status) as these often are highly correlated with the chosen treatment. The sensitivity analysis also addressed the baseline difference in tumor size occurring between the control- and intervention groups, as randomization was not stratified for tumor size. Our study is further limited by the unblinded nature of the intervention, although this is a limitation of all behavioral interventions with a care as usual control group, as well as limited power for moderation analyses, no records of compliance or dropouts, and the 43% nonparticipation rate, which we have however utilized to address differences between participants and non-participants.

The main limitation of our study is the limited sample size, which may the reason our findings can neither support there being an effect of psychosocial interventions on survival, nor convincingly contradict it. Post hoc calculations revealed that for the given design and a power of 80%, the minimal detectable HRs were 0.43 and 1.87 when comparing the intervention group with the control group (Supplemental Material 1). Given that also effects closer to the null are clinically relevant, the current study was not large enough to have a high power for detecting all clinically relevant effects. Despite the limited power, we believe the data presented add to the knowledge base for future studies in this field and could add a further piece of the puzzle for future meta-analyses.

Our study population was slightly different compared to the original study with four year follow-up [Citation21], as we selected the population based on an “intention-to-treat” approach. This was done before we retrieved data for the survival outcome, keeping the selection independent and unbiased. The ‘intention-to-treat’ approach tends to underestimate the effect size of the intervention in case of noncompliance or non-adherence [Citation40], so our estimate may be correspondingly conservative.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we did not observe that the psychosocial intervention in patients with early-stage breast cancer significantly improved overall survival. Yet, based on the limited sample size, our results also do not allow us to reject a possible effect.

We confirmed that participants and non-participants differed statistically significantly at baseline in age, cancer stage, and receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, however, when adjusted for strong prognostic factors, our analysis did not reveal a statistically significant survival difference between these two groups of patients. However, we cannot rule out a possible prolonged survival among participants due to the limited power.

Based on our findings, we are not able to confirm nor discount the promise of longer life expectance convincingly as an evidence-based benefit of psychosocial interventions for women with early-stage breast cancer.

Ethical approval & trial registry information

The original trial was a two-arm RCT, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, registered at clinicaltrail.gov (NCT01108224), and approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Copenhagen County (KA 04005). All participants provided informed consent.

Author contributions

Anne Marie Kirkegaard: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Susanne Oksbjerg Dalton: Resources, funding acquisition, and writing-review and editing. Ellen Helle Boesen: Conceptualization, software, investigation, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, and writing-review and editing. Randi V. Karlsen: Conceptualization, software, investigation, methodology, and writing-review and editing. Henrik Flyger: Conceptualization, and writing-review and editing. Christoffer Johansen: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, and funding acquisition. Annika von Heymann: Conceptualization, supervision, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors thank Jorne Biccler for statistical assistance.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AH, upon reasonable request and in compliance with European and national laws governing consent and data security.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antoni MH, Knight JM, Lutgendorf SK. Psycho-Oncology, stress processes, and cancer progression. In: Breitbart W et al., editors, Psycho-Oncology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021. p. 636–643.

- Dalton SO, Boesen EH, Ross L, et al. Mind and cancer: do psychological factors cause cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(10):1313–1323.

- Nakaya N, Tsubono Y, Hosokawa T, et al. Personality and the risk of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(11):799–805.

- Bleiker EMA, Hendriks JHCL, Otten JDM, et al. Personality factors and breast cancer risk: a 13-Year follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(3):213–218.

- Nakaya N, Bidstrup PE, Saito-Nakaya K, et al. Personality traits and cancer risk and survival based on finnish and swedish registry data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):377–385.

- Boesen E, Johansen C. Impact of psychotherapy on cancer survival: time to move on? Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:372–377.

- Spiegel D, Kraemer H, Bloom J, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;334(8668):888–891.

- Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive‐expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: survival and psychosocial outcome from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):277–286.

- Cunningham AJ, Edmonds CVI, Jenkins GP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of group psychological therapy on survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psycho Oncol. 1998;7(6):508–517.

- Edelman S, Lemon J, Bell DR, et al. Effects of group CBT on the survival time of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Psycho Oncol. 1999;8(6):474–481.

- Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1719–1726.

- Spiegel D, Butler LD, Giese-Davis J, et al. Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized prospective trial. Cancer. 2007;110(5):1130–1138.

- Kissane DW, Love A, Hatton A, et al. Effect of Cognitive-Existential group therapy on survival in Early-Stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4255–4260.

- Stagl JM, Lechner SC, Carver CS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in breast cancer: survival and recurrence at 11-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(2):319–328.

- Andersen BL, Yang H-C, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3450–3458.

- Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3570–3580.

- Kissane DW, Bloch S, Smith GC, et al. Cognitive‐existential group psychotherapy for women with primary breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2003;12(6):532–546.

- Stagl JM, Antoni MH, Lechner SC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral stress management in breast cancer: a brief report of effects on 5-year depressive symptoms. Health Psychol. 2015;34(2):176–180.

- Stagl JM, Bouchard LC, Lechner SC, et al. Long‐term psychological benefits of cognitive‐behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11‐year follow‐up of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2015;121(11):1873–1881.

- Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(5):494–501.

- Boesen E, Karlsen R, Christensen J, et al. Psychosocial group intervention for patients with primary breast cancer: a randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(9):1363–1372.

- Jassim GA, Doherty S, Whitford DL, et al. Psychological interventions for women with non‐metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;1(1):CD008729.

- Mirosevic S, Jo B, Kraemer HC, et al. “Not just another meta-analysis”: sources of heterogeneity in psychosocial treatment effect on cancer survival. Cancer Med. 2019;8(1):363–373.

- Andersen BL. Biobehavioral outcomes following psychological interventions for cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(3):590–610.

- Lillquist PP, Abramson JS. Separating the apples and oranges in the fruit cocktail: the mixed results of psychosocial interventions on cancer survival. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;36(2):65–79.

- Boesen E, Boesen S, Frederiksen K, et al. Survival after a psychoeducational intervention for patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma: a replication study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5698–5703.

- Berglund G, Bolund C, Gustafsson U-L, et al. Is the wish to participate in a cancer rehabilitation program an indicator of the need? Comparisons of participants and Non-Participants in a randomized study. Psycho Oncol. 1997;6(1):35–46.

- Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52(12):1143–1156.

- Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, et al. Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2010;33(1):1–14.

- Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B, Jensen M-B, et al. Danish breast cancer cooperative group. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:445–449.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549.

- Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer: a randomized prospective outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):527–533.

- Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):305–338.

- Demark‐Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, et al. Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(3):167–189.

- Olsson I-M, Malmström M, Rydén L, et al. Feasibility and relevance of an intervention with systematic screening as a base for individualized rehabilitation in breast cancer patients: a pilot trial of the ReScreen randomized controlled trial. JMDH. 2022;ume 15:1057–1068.

- Envold Bidstrup P, Mertz BG, Kroman N, et al. Tailored nurse navigation for women treated for breast cancer: design and rationale for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(9-10):1239–1243.

- Würtzen H, Dalton SO, Andersen KK, et al. Who participates in a randomized trial of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) after breast cancer? A study of factors associated with enrollment among danish breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):1180–1185.

- Fukui S, Kugaya A, Kamiya M, et al. Participation in psychosocial group intervention among japanese women with primary breast cancer and its associated factors. Psychooncology. 2001;10(5):419–427.

- Boesen E, Boesen S, Christensen S, et al. Comparison of participants and Non-Participants in a randomized psychosocial intervention study Among patients With malignant melanoma. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(6):510–516.

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: wilkins; 2008.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563–591.