Abstract

Background

After primary treatment, patients with early breast cancer (EBC) are followed-up for at least 5 years. At the Helsinki University Hospital (HUS) surveillance includes appointments at 1, 3 and 5 years, and between pre-planned visits a phone call service operated by a nurse practitioner for counseling about symptoms related to side-effects or potential recurrence. In 2015 HUS launched a digital solution for cancer patients. This study was designed to find out patient preference, Health related (HR) quality of life (QOL) and satisfaction with a digital solution compared to a phone call service during the first year of follow-up.

Material and methods

Patients with EBC were randomized at the final visit of radiotherapy to surveillance by phone calls or by the digital Noona solution during the first year outside pre-planned visits. After six months the groups were crossed over to the other arm. Primary endpoint was patient preference for either follow-up method among those who had contacted the study nurse at least once by both phone service and digital solution.

Results

Out of the 765 patients randomized, 142 had contacted the hospital with both methods and were eligible for inclusion in the analyses of the present study. Out of the 142 patients, 56 preferred phone calls, 43 the digital solution while 43 considered both modalities equal. Preference for the digital solution was higher among patients aged 65 or less. There were no differences in HR QoL or overall satisfaction between the modalities. However, the patients rated the timeliness of response better while using the digital solution.

Conclusion

Of the patients 30% preferred the digital solution, 40% phone calls while 30% found them equal as the primary follow-up method for EBC during the first year outside pre-planned visits. There is a need to include also digital solutions in surveillance of EBC.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

NCT04980989

Background

Scientific evidence for telehealth technology applications is needed as their use in numerous areas in healthcare expands [Citation1].

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females in the Western world. Most patients have local disease at primary diagnosis [Citation2]. About 20% of breast cancer patients will later be diagnosed with a recurrence. After primary treatment, patients with early breast cancer are followed up for at least 5 years [Citation3]. Most patients with estrogen receptor-positive tumors receive endocrine treatment for 5–10 years. All treatment modalities of breast cancer may cause long time morbidity.

According to the guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the aims of follow-up of breast cancer are to detect early local recurrences or contralateral breast cancer, to evaluate and to treat therapy-related complications, to motivate patients to continue hormonal treatments, and to provide psychological support and information in order to enable a return to normal life [Citation3].

In 2000 at the Comprehensive cancer center (CCC) of the Helsinki University Hospital (HUS), regular appointments during five-year surveillance were reduced to three, at one, three and five years after primary diagnosis since 10-year follow-up of a randomized study showed that intensive diagnostic follow-up of EBC had no impact on overall survival [Citation4]. At the same time, a phone call service operated by breast cancer nurse practitioners was set up for patients who needed counseling about symptoms related to side effects or potential recurrence between preplanned visits.

However, phone call services are time-consuming and may become overloaded whereupon patients do not reach nurses as easily as needed. The use of digital services is increasing, and more and more people are used to doing errands or seeking information digitally via the Internet whenever it is most convenient for them. Moreover, the combination of an increasing number of breast cancer survivors and limited healthcare resources has raised the interest in developing digital communication methods between patients and healthcare personnel.

Measuring and identifying patients’ individual problems and care needs can be achieved by patient-reported outcomes (PROs). PRO comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else [Citation5]. Symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are examples of information suitable for reporting as PROs [Citation6]. An electronic PRO Measure (ePROM) is an online question or questionnaire that is used to collect ePROs. Previous studies have shown that use of PROMs increases patient satisfaction [Citation7]. ePRO-symptom monitoring at prespecified intervals can contribute to timely health risk detection and subsequently allow earlier intervention [Citation8–10].

HUS CCC developed an electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) digital solution for cancer patients together with a Finnish startup company. The Noona solution is a web-based application enabling patients to contact cancer nurses between pre-planned appointments and self-report symptoms or adverse events of treatments by completing ePROMs via a computer or smart mobile devices [Citation11]. The nurse practitioners answer the questions digitally and send care instructions. The first module of the digital Noona solution was tailored for the follow-up of EBC.

A prospective controlled randomized cross-over study was designed to find outpatient preference for the modality of surveillance as the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints were patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life (HR QoL) during surveillance modalities. The aims of this study were to investigate whether a digital solution would be accepted by a large majority of patients instead of a conventional phone call service.

Material and methods

Patients

Eligibility criteria included age ≥ 18 years and histologically confirmed EBC or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Exclusion criteria included presence of distant metastases, another malignant tumor, or severe cognitive failure. Patient eligibility was screened during postoperative radiotherapy. Patient recruitment lasted from 17th July 2015 to 2nd January 2017.

The standard procedure of follow-up of EBC at HUS

As standard therapy patients with EBC at HUS receive at their last visit of radiotherapy a printed leaflet on the routine surveillance of EBC including instructions when to contact the hospital outside preplanned appointments, i.e., if they have symptoms that may be related to adverse events of therapy, disease recurrence or if they have other questions or worries. Additionally, nurse practitioners follow written routine standard operational procedure (SOP) in their response to these contacts of patients with EBC. Pre-planned visits were at 1, 3 and 5 years from primary diagnosis. In addition, breast imaging was done yearly.

The digital Noona solution

Noona® is a patient outcomes management solution designed to engage patients in their care with real-time symptom reporting and monitoring, The first module of the digital Noona solution was the module for follow-up of EBC and it was designed in collaboration with HUS. The symptom questionnaires and answers to the most common questions were designed according to the contents of the standard operational procedure (SOP) for breast cancer nurse practitioners on the follow-up of EBC.

In the first page of the questionnaire was listed and asked if the patient had any of the most common symptoms related to BC recurrence or adverse events of treatments. Additionally, there was an open question where the patient could report any other symptoms. If the patient reported having symptoms (any of the listed ones, or as free text) a further questionnaire related to the severity of the symptom according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) came into view. The Noona solution was designed in collaboration with senior experts in clinical breast oncology and IT solutions.

Study design

This study was a prospective, open-label, and randomized cross-over clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT04980989). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to entry into the study. The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local ethical and legal requirements. The protocol and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Helsinki University Hospital (HUS), Finland (Dnro 112/13/03/2015).

At the final visit of adjuvant radiotherapy patients were recruited and randomized to surveillance during the following year outside preplanned visits by means of standard phone calls or the interventional digital Noona solution. Group A used the digital solution first and Group B the phone call service. After the first six months, the groups crossed over to the other follow-up method for a further six months of follow-up. The study nurse informed the patient when it was time to change the follow-up method and activated or de-activated the access to the digital solution. The Noona solution was only available for the patients in the study during the study. All patients were thus exposed to both follow-up methods, the order of which was determined by randomization. The aim of randomization in this study was not to detect any differences between the two randomized arms but to enable each patient to compare the two follow-up methods and eliminate the possibility that any difference would be due to the order of the two sequential follow-up methods.

At the beginning of follow-up all patients were given a printed leaflet on the routine surveillance of early breast cancer including instructions on when to contact the hospital, i.e., if patients have symptoms that may be related to adverse events of therapy, disease recurrence or they have other questions or worries. Additionally, during both follow-up modalities, the nurse practitioners acted according to the written routine standard operational procedures (SOP) for patient contacts during the surveillance of EBC.

During follow-up by digital solution, the patients communicated with breast cancer nurse practitioners by asking questions or reporting symptoms by using structured questionnaires that were designed to find out more about the symptoms possibly related to breast cancer recurrence or adverse events of treatments. The nurse practitioners digitally answered the questions and sent care instructions during the same working day. They could utilize a library of standard answers to the most common questions. During both follow-up modalities the nurses consulted an oncologist if needed according to SOPs. According to the study protocol breast cancer nurse practitioners reported all patient contacts and the duration of each contact.

Outcome measures

At 12 months the patients were asked in a written paper questionnaire if they preferred to use the digital Noona solution (Supplemental Table 1), telephone call service or both. Preference was analyzed as the primary endpoint after the patients had contacted the breast cancer nurse practitioner at least once with both modalities. The patients were also asked reasons for their preference with free text fields.

In addition, patients completed a written paper satisfaction survey at 6 and 12 months. The questionnaire for patient satisfaction was designed for the present study (Supplemental Table 1) since no validated questionnaires to address the purpose of the present study were available at the time of study design. The score of the questionnaire ranges between one and four. The overall satisfaction score was calculated as the mean of the scores for questions 1–15.

The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core30 questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) [Citation12] with its breast cancer-specific module (EORTC QLQ-BR23) [Citation13] and the generic 15D which is a 15-dimensional questionnaire providing both a health profile and a preference-based single index score [Citation14]. The patients answered HRQoL questionnaires on paper at baseline and at 6 and 12 months thereafter. The questionnaires were on paper since digital versions were not available at the time of study design.

The breast cancer nurse practitioners recorded all contacts and the time spent responding to each contact.

Statistical analyses

The primary endpoint was a patient preference among patients who contacted the breast cancer nurse practitioner by both follow-up modalities and only these patients were analyzed in the present report. According to historical data from HUS CCC it was estimated that about 10% of the patients would contact the hospital outside preplanned visits twice during the first year of follow-up of EBC. The study was dimensioned to be able to estimate the preference or acceptance (preference plus the proportion stating no preference for any of the methods) with a confidence interval of approximately 10%. To achieve this, we decided to randomize about 800 patients during a planned inclusion period of 1.5 years. As the number of patients (765) at the end of the planned recruitment period was close to 800, we stopped randomization in January 2017.

Patient preference was tested with the related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test coded as three alternative ordinal variable values, preference for follow-up with the digital solution, no preference or preference for follow-up with the phone call service. Exact confidence intervals for preference were calculated according to the method of Clopper-Pearson. Factors associated with preference for follow-up with digital solution were compared to no preference or preference for follow-up with phone calls and tested in a binary logistic regression model.

Patient satisfaction and HRQoL were tested in a repeated measurements linear model including also the randomization arm in order to take the time (first or second six months period) of follow-up into account. Patients who completed the questionnaires at both 6 and 12 months were included in the statistical analyses. Differences due to follow-up method (digital solution or phone calls) were tested as a within-patient factor including the randomization arm as a between-patients variable and also the interaction between randomization arm and follow-up method. Thus, in the comparison of the two follow-up methods, the patient served as her own control, and the p-value for the follow-up method tests the mean difference between these methods. The p-value for the randomization arm tests the effect of the order of the two follow-up methods, and the interaction term whether the follow-up period (first or second six months) had any impact on the difference between follow-up with the digital solution or phone call service.

Differences in scores for the 15 separate questions of the satisfaction questionnaire between the two follow-up modalities’ scores were tested with the nonparametric, related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank test, since the distribution of scores did not always necessarily fulfill the requirements for the repeated measurements linear model.

Mean contact time was the time the nurse spent in replying to each contact.

Descriptive statistics were computed for the digital Noona solution and phone call groups at baseline, six and 12 months. The results were expressed as integers and proportions for discrete variables, and as mean values and standard deviation or median and range for continuous variables depending on the data distribution and statistical test used.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 25). The limit for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patients

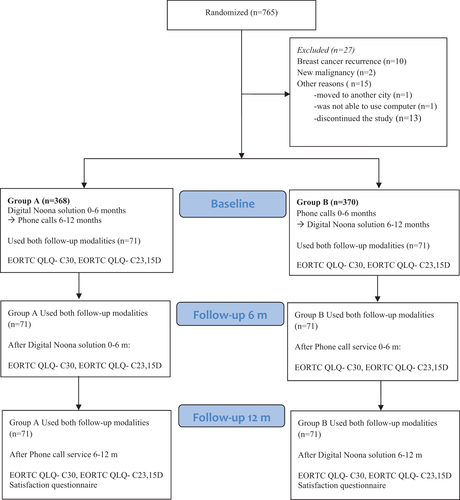

Seven hundred and sixty-five patients with early breast cancer were randomized to surveillance by phone calls or by the digital Noona solution. For details about patient inclusion, see the flow chart in . Ten patients were excluded due to breast cancer recurrence (1.3%) and two patients due to a new malignancy (0.3%). Fifteen patients discontinued the study owing to some other reason (2.0%). Of these, one patient moved to another region, another patient was not able to use the computer and the rest preferred not to continue. Thus, 738 patients completed both follow-periods. Out of the patients, 292 (39%) did not contact the hospital at all during the first year of early breast cancer surveillance. One hundred forty-two patients (19%) contacted the breast cancer nurse at least once with each follow-up modality (digital solution and phone calls) and were included in the present analysis.

The characteristics of the patients and tumors are shown in . The median age was 60 years (range 35-–79). All were female. The majority of the participants had ductal (66%), T 1, (73%) grade 2 (41%), and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (86%). The patients contacted the breast cancer nurse between 1 and 17 times (median 2) during the digital solution follow-up period and between 1 and 6 times (median 1) during the phone call follow-up period. Mean number of contacts and meantime allocated by the breast cancer nurse during the first and second six months of follow-up and follow-up method are shown in . The number and times of contacts were higher during the first period (mean 2.14 contacts and 19.8 min) than during the second period (mean 1.88 contacts and 17.4 min). Both the mean number of contacts and mean time allocated by the breast cancer nurse were higher while using the digital solution during both periods.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 2. Contacts and satisfaction score during both follow-up modalities at 6 and 12 months.

Outcomes

Fifty-six patients (40%, 95% confidence interval 31– 48%), preferred phone calls and 43 digital solutions (30%, 95% confidence interval 23–39%) while 43 patients (30%) considered both modalities equal. The difference in preference for the two modalities was not statistically significant (p = 0.191). Patient acceptance, i.e., preference plus proportion stating no difference, was 70% (95% confidence interval 62–77%) for phone calls and 61% (95% confidence interval 52–69%) for the digital Noona solution. Randomization arm, educational level (high school or not) and age were tested as predictive factors for preference of follow-up method. Only age was significantly associated with preference (p = 0.002), with 36/94 (38%) of patients aged 65 or less preferring follow-up with the digital solution compared to 7/48 (15%) for the older ones. According to written free-text comments on the questionnaires, most patients who preferred phone calls valued personal contact, and the ones choosing digital solution easiness to contact or the possibility to use their own language.

Secondary endpoints included patient satisfaction and HRQoL. Patient satisfaction score was high in both groups as shown in . There was no difference in mean satisfaction scores between the groups in terms of follow-up modality (p = 0.59). Mean patient satisfaction score improved from the first (mean 3.29) to the second time period (mean 3.41), (p = 0.04 for interaction between randomization group and follow-up time).

Table 3. Quality of life during both follow-up modalities at 6 and 12 months.

As for the differences in scores for the 15 separate questions of the satisfaction questionnaire (Supplemental Table 1) 104 patients rated the timeliness of responding to their request better for the digital solution (mean score 3.6/4) than for the phone call service (3.5/4) p = 0.03. The proportion of patients, who rated the timeliness as excellent (score 4) was 74% (n = 90/122) for the digital solution and 65% (n = 77/119) for the phone call period. No other significant differences in scores for the separate questions of the satisfaction questionnaire were found. In both groups, the majority of patients reported that they knew where to contact, if necessary (92% (n = 127/138) and 91% (n = 127/139), scored 3 or 4 for the digital solution and hone call periods, respectively) and that nurses responded professionally to their problems (89% (n = 103/116) and 87% (n = 96/111), respectively). Most patients noted that they had been supported psychologically well (74% (n = 53/72) and 80% (n = 63/79), respectively) and they had felt safe (84% (n = 106/127) and 77% (n = 94/122), respectively).

QLQ-C30 questionnaires were completed by all 142 participants, and the 15D questionnaire by 139 patients (). No significant differences between the two follow-up modalities were found in global quality of life score according to the EORTC (p = 0.15) or 15D score (p = 0.59), nor were there any difference in HR QoL between the first and second 6-month periods (p-value for interaction between randomization group and follow-up method p = 0.77 and 0.09, respectively).

Discussion

Due to the lack of evidence of survival benefits from routine examinations, HUS CCC started the more individualized phone call service-based follow-up of EBC already in 2000 with only three pre-planned visits during five years. In the present study, our primary aim was to find out whether patients would prefer a digital solution after having had experience of both follow-up modalities during the first year. Nineteen percent of the patients with EBC contacted the breast cancer nurse at least once during the first year with both the digital solution and phone call. Of these 40% preferred phone calls, 30% the digital solution, and 30% considered both methods equal. Consequently, 60% of the patients were willing to use digital software as the primary method for communication with the hospital between preplanned visits. This is a high proportion of patients in a highly personal and sensitive matter like breast cancer surveillance indicating a need for also including the availability of digital solutions in the follow-up of EBC. Seventy percent of the patients preferred using either one of the two methods, with similar proportions preferring the digital and phone call solution, indicating the diverse preferences and needs of different patient groups. This was also illustrated by the difference in preference by age. Thirty-eight percent of patients aged 65 or less prefer mobile software follow-up compared to 15% for the older ones. The median age of 60 in the present study is well representative for patients with EBC. Altogether the patient preference results indicate, that to satisfy the needs of the majority the health service ideally should provide both a conventional telephone service and a digital solution.

In a Danish study 124 patients with EBC were randomized to standard follow-up including visits every six months or to ePRO-based follow-up with a secure link to complete an electronic questionnaire every three months [Citation15,Citation16]. Patients’ experience of care was similar in both groups, but with a tendency toward more involvement, higher satisfaction rate and a lower percentage of unmet needs among women in the ePRO-based surveillance. Riis et al. also concluded that their findings justify further actions toward implementing ePROs in follow-up care. Moreover, the use of ePRO-based individualized follow-up could change the organization of follow-up care and re-allocate services for those in need of it. In fact, presently many breast cancer patients are treated with endocrine treatment up to 10 years which means increasing number of patients in need of surveillance. Patients with very high-risk early breast cancer might benefit from surveillance extending beyond the end of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Also in the present study, the patients rated their mean satisfaction score equal for the two follow-up periods but reported higher satisfaction with timeliness during the digital solution period. This may be one of the advantages with a digital follow-up program. Digital solutions enable patients to contact the hospital easily whenever most convenient for them.

Interestingly, number and times of contacts were higher during the first period than during the second period. Both mean number of contacts and mean time allocated by the breast cancer nurse were higher while using the digital solution during both periods. A similar finding of increased contacts with a digital solution was also seen in the study by Bärlund et al. [Citation17]. Taken together, this indicates that digital PROMS enable more detailed documentation and follow-up of the symptoms but on the other hand, easier access to the care team may also increase the workload of dealing with contacts.

Our study included only the first year of follow-up when breast cancer recurrence is quite rare. However, in some patients, disease recurrence has to be ruled out because of symptoms. Additionally, many patients experience adverse events during endocrine therapy and may need counseling or medication to alleviate the symptoms. Moreover, some patients may need mental support or rehabilitation to recover from the disease or adverse effects of the treatments. In fact, digital coaching for a healthy diet and exercise to support the recovery might be feasible for patients with EBC [Citation3].

Takala et al. investigated the usefulness of PROs with the module for radiotherapy (RT) of the same digital Noona solution during adjuvant radiotherapy of 253 patients with EBC in a real-world setting [Citation18]. They found out that patients were motivated to use the ePRO system, and the response rates were high (82.5%). During RT, 39.3% of the ePRO responses were about symptoms and 60.7% were about treatment-related questions or advice. Patients seemed to find that the ePRO system was an easy way to contact their own health care professionals.

Richards et al. found that use of the ePRO system for the real-time, remote monitoring of symptoms in patients recovering from cancer-related upper gastrointestinal surgery is feasible and acceptable [Citation19].

In the intervention group, responses to ePROs were used to screen for symptoms, detect declines in function or quality of life, and tailor follow-up care to the individual needs of the patient.

Participants found the ePRO system reassuring, providing timely information and advice relevant to supporting their recovery. Clinicians regarded the system as a useful adjunct to usual care.

Digital systematic weekly follow-up of cancer patients with metastatic disease during chemotherapy may even have an impact on treatment outcome and on the use of health-care services [Citation8–9]. Additionally, after primary treatment 133 lung cancer patients with stage III/IV disease were randomized to traditional surveillance or to use the digital Moovcare application once a week [Citation10]. The software analyzed 12 symptoms with algorithms and reported the results to oncologists who confirmed the suggested procedures. In the web application arm the disease recurrence was noted earlier, fewer imaging tests were done, quality of life was better and the median survival was seven months longer.

Along with the Covid19 pandemic, the need for remote services also for cancer patients have grown rapidly [Citation20]. The majority of the patients in an Irish study felt that there should be a role for a virtual clinic in the future [Citation21]. Digital follow-up with PROMs instead of preplanned visit during follow-up enables remote contacts and staying at home. It has been suggested that patients in the future will be seen less often in person at the hospital and that broad implementation of remote digital services will increase virtual contacts with personal nurses and doctors [Citation22]. However, the patient preference results of our study indicates that at least presently all patients are not able or willing to use digital equipment. Therefore, preferentially, the patients themselves should be able to choose the follow-up modality that best suits them [Citation23]. Well-designed digital services with dedicated care-giving teams may in the future be the best option for many patients when proven feasible at that point of the patient path.

In conclusion, thirty per cent of the patients preferred to contact breast cancer nurse by the digital solution, forty per cent preferred phone calls while thirty per cent found them equal in the follow-up of EBC between pre-planned visits during the first year. Patient satisfaction was high for both digital solution and phone call service, but the patients rated the timeliness of response better during the digital solution follow-up period. Due to the diversity of patients’ needs, the follow-up service should ideally contain both possibilities, a digital solution in addition to a possibility of personal phone contact.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families who made this trial possible. We also thank study nurses Satu Forsström, Kaisa-Liisa Heikkilä and Riitta Mustonen for their assistance in collecting the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins M. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1585–1592.

- Harbeck N, Gnant M. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1134–1150.

- Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1194–1220.

- Palli D, Russo A, Saieva C, et al. Intensive vs clinical follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: 10-year update of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1586.

- Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measuresuse-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims. (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- van den Hurk CJG, Mols F, Eicher M, et al. A narrative review on the collection and use of electronic patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivorship care with emphasis on symptom monitoring. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(6):4370–4385.

- Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1480–1501.

- Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565.

- Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–198.

- Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, et al. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djx029.

- https://www.varian.com/products/software/care-management/noona.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–2768.

- Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):328–336.

- Riis CL, Jensen PT, Bechmann T, et al. Satisfaction with care and adherence to treatment when using patient reported outcomes to individualize follow-up care for women with early breast cancer – a pilot randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(4):444–452.

- Riis CL, Stie M, Bechmann T, et al. ePRO-based individual follow-up care for women treated for early breast cancer: impact on service use and workflows. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(4):485–496.

- Bärlund M, Takala L, Tianen L, et al. Real-world evidence of implementing eHealth enables fluent symptom-based follow-up of a growing number of breast cancer patients with the same healthcare. Clin Breast Cancer. 2022;22(3):261–268.

- Takala L, Kuusinen TE, Skyttä T, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcomes during breast cancer adjuvant radiotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2021;21(3):e252-70–e270.

- Richards HS, Blazeby JM, Portal A, et al. A real-time electronic symptom monitoring system for patients after discharge following surgery: a pilot study in cancer related surgery. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):543.

- Liu R, Sundaresan T, Reed ME, et al. Telehealth in oncology during the COVID-19 outbreak: bringing the house call back virtually. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract. 2020;16(6):289–293.

- O’Reilly D, Carroll H, Lucas M, et al. Virtual oncology clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;190(4):1295–1301.

- Patt DA, Wilfong L, Toth S, et al. Telemedicine in community cancer care: how technology helps patients with cancer navigate a pandemic. J Clin Oncol Pat Pract. 2021;17(1):e11–e15.

- Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205873.