Abstract

Background

As earlier studies found that early onset specialized palliative care (ESPC) results in better quality of life (QoL), less hospitalization and chemotherapy toward end-of life, we implemented ESPC in our oncology outpatient clinic. The aim of this study was to describe reasons for referral, interventions performed and the satisfaction among the oncologic staff.

Material and Methods

The outpatient ESPC clinic was established in the department of oncology. Prespecified selected data was obtained from the patients records. All patients were asked to fill in a questionnaire concerning their symptoms and QOL. A survey among the oncologic personnel concerning their perception of the clinic was conducted. All data were consecutively collected in a share point database.

Results

We included 134 patients. The primary referral symptoms were pain (69%) or psychological/existential challenges (23%). 55% of patients filled in an EORTC questionnaire and rated a median (QoL) of 3.4. Interventions initiated were on based on the following symptoms: pain (70%), constipation (53%), nausea (15%), dyspnea (10%) and depression (7%). Median waiting time was 13 days. Of the 134 patients referred to the ESPC clinic 101 was admitted. Symptoms and problems were resolved in the ESPC clinic for 81 of the 101 admitted patients (80%), i.e., after one consultation for 25 patients and after a follow up course in the clinic for 56 patients. A survey among the staff at the Department of Oncology demonstrated a high degree of satisfaction with the ESPC clinic.

Conclusions

We report experiences from implementation of ESPC in our outpatient oncologic clinic, where 81 (80%) of the admitted patients could be finished after one or a few follow up contacts, as their symptoms had been resolved. There was a high degree of satisfaction with the clinic among the oncologic staff.

Introduction

Traditionally, specialized palliative care (SPC) has been initiated as part of the oncologic patient trajectory when palliative treatment is no longer possible and life-prolonging chemotherapy was terminated. In recent years, this paradigm has shifted, and palliative care is thought to – ideally – be an integrated part of the treatment course of oncologic patients, preferably with an early onset. In 2018, Kaasa et al. [Citation1] published recommendations of how, systematically to integrate palliative care, addressing several areas of action. A key area is awareness of palliative care needs in seriously ill patients in a busy outpatient oncology setting. Another area is enhancing cooperation between the oncology staff and SPC workers, hence increasing symptom management among patients as well as improving basic palliative skills among the oncology staff. Studies have shown that early integrated palliative care not only reduces symptom burden and improves quality of life [Citation1–5] but also reduces proportion of hospitalization in the last two months of life [Citation6] and the use of intensive cancer treatment at the end of life [Citation7–8]. Furthermore, a randomized study showed that when offered early palliative support, a larger amount of patients die in the comfort of their own home, and they spend less time at hospitals and more time at home or in nursing homes [Citation9]. In 2017, the Danish Health Authorities recommended a palliative approach for all patients with life threatening disease, and that palliative care was to be provided as early as at the time of first palliative diagnosis [Citation10]. Furthermore, the goal was set for these patients to have access to SPC within 10 days of referral. Based on these recommendations we implemented an outpatient clinic for early specialized palliative care (ESPC). It was introduced exclusively for patients with a non-curable malignant diagnosis and was physically placed directly in our oncologic outpatient clinic. The patients were booked for an assessment in the ESPC clinic while they were either still in an active oncological course, receiving oncological treatment, or while they were in a follow-up course.

The focus was on the symptoms that empirically have a large impact on the everyday life of the palliative cancer patients and their families, i.e., pain, dyspnea, anxiety, nausea, constipation, anorexia and psychosocial and existential issues. In addition, we wanted to promote the cooperation between the oncology and the specialized palliative care staff, hence increasing the palliative skills among the staff in the Department of Oncology.

The aim of this study was to describe the implementation process; our patient population based on pre specified clinical observations. Furthermore, to evaluate the satisfaction among the oncologic staff and thereby contribute to the expansion of ESPC into the oncologic society.

Method

Prior to the onset of the ESPC clinic, physicians from our local SPC team introduced the oncologic staff, nurses and physicians to the idea of the outpatient clinic. The introduction was completed at several meetings where the staff was educated about ‘the typical palliative patient’ according to physical symptoms and awareness of psychosocial and existential conditions. Furthermore, we wrote a pamphlet describing the concepts of the ESPC clinic. Both doctors and nurses from the oncologic department could refer patients for the ESPC clinic when identifying palliative needs, which were not handled in the traditional oncological setting. The clinic was located directly in the oncologic outpatient clinic. Patients were seen by a SPC physician and an oncologic nurse in an one hour consultation. Follow up consultations of 30-minute sessions were available if needed. Follow-up sessions could be conducted by physical attendance or by telephone, depending on patient’s preferences.

According to RECORD guidelines [Citation11] data were continuously entered into a SharePoint™ database. Sex was defined as a binary variable corresponding to the biological sex registered. Age at referral as a continuous variable, type of cancer sorted into groups according to cancer site, type of oncologic therapy categorized into (chemotherapy/other cytostatic therapy/radiotherapy/no active treatment), civil status categorized as living alone or together with a partner, employment status categorized as working, retired or off work sick. All patients were asked to fill out the patient self-assessment questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 [Citation12] at the first visit. In this questionnaire, a total of 30 common symptoms are lined out and the patient is asked to grade these symptoms as ‘1’ Not at all, ‘2’ A little, ‘3’ Quite a bit or ‘4’ Very much. Furthermore, rating of overall health and rating of quality of life (QOL) on a numeric rating scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is very poor and 7 is excellent was performed. We registered the reason for referral to the ESPC clinic, given by the referring staff and the presence of several physical symptoms as pain, nausea, constipation and dyspnea as well as psychosocial and existential symptoms such as anxiety and depression unveiled during the consultation. Interventions performed in the ESPC clinic as prescription of analgetics, laxatives, medication against nausea, depression and anxiety was registered. Furthermore, we recorded if the ESPC clinic referred patients to other interdisciplinary interventions as social workers, psychologist, physiotherapist or home care nurses. The patients were finished from the clinic in cases, where as well the patient as the staff agreed, that their complaints were resolved. The Danish Palliative Care Database [Citation13] recommends a waiting time of a maximum of ten days for patients referred to SPC. There is no golden standard for waiting time for basic palliative care needs. We recorded waiting time to the ESPC clinic from date of referral to first visit. For follow-up we registered if and how many times patients were seen in the ESPC clinic and to which instance patients were allocated after the clinic; either department of oncology, their general practitioner or a SPC team. The purpose of the follow- up was to complete the initiated palliative effort within a limited number of consultations. In case of complex symptoms not possible to solve in the ESPC clinic patients were referred directly to the SPC team. Patients were followed until death regarding registration of later referral to a SPC team. To investigate potential differences between patients seen in the ESPC clinic and patients referred to the SPC team we looked at median survival as a surrogate marker for early referral. Median overall survival was obtained for patients referred to and seen in the SPC team in 2021. After one year, we conducted a written survey among the referring staff in the oncologic department (doctors and nurses). The questions asked were whether the ESPC clinic contributed in a positive way to the oncologic outpatient clinic, whether they found it helpful in their daily work and whether they found that the clinic was helpful for the patients.

Statistics

All data were analyzed with the statistical software package STATA™. We used non-parametrical statistics. Numerical values are shown as median (range). For survival analysis, log rank analysis was performed and survival time was illustrated using a Kaplan–Meier plot.

Results

In total, 134 patients consulted the ESPC clinic from January 1st to December 31st 2021. Their clinical baseline characteristics appear from . As shown, about two thirds of all patients had pulmonary, breast or gastrointestinal cancer. Two thirds of patients were receiving oncologic treatment at the time of assessment in the ESPC clinic, whereas approximately one third did not. Reasons for referral to the ESPC clinic appear from .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Table 2. Reason for referral.

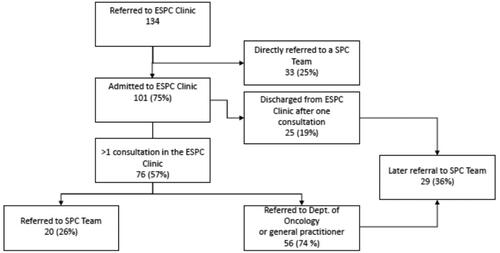

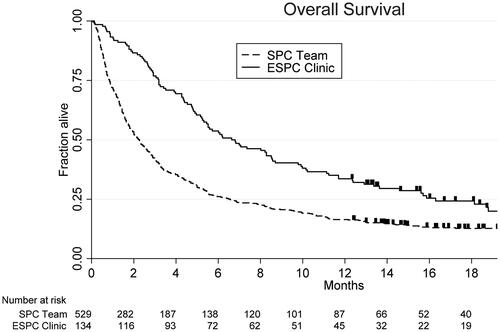

The most prominent reason was the need for optimization of pain management, identified as the most frequent complaint in nearly 70% of patients. In one third of patients, the referring staff had identified more than one complaint. The interventions given in the ESPC clinic are listed in . As illustrated, several other symptoms or complaints were unveiled during the consultations. Besides pain management, constipation was the most prevalent symptom, present in more than half of patients. Further symptoms that required medical intervention were nausea, dyspnea and mental depression. Of the 134 included patients, QOL was reported in 74 (55%). Median QOL among these patient was 3.4 (range 1–7). Median waiting time to the ESPC clinic was 13 (0–40) days and only 40% were seen in the ESPC clinic within 10 days of referral. In order to investigate if patients seen in the ESPC clinic had earlier access to SPC compared to the population in our SPC team we looked at patient survival time. A total of 529 patients were referred to and seen by the SPC team in 2021. The median survival for ESPC patients was 6.6 (5.2–18.5) months, whereas the median survival for the population in the palliative team was 2.2 (1.9–2.6) months. illustrates a Kaplan Meier plot for patients seen in the ESPC clinic and SPC team. Amongst the 134 patients, 76 patients (57%) had a follow up course in the clinic as illustrated in the flowchart in . illustrates the number of follow up visits in ESPC. Fifty-six (74%) patients were completed in the ESPC clinic as it was possible to resolve their palliative problems in this setting. Thirty-three patients (25%) were referred directly to the SPC team due to complex palliative care needs, requiring an interdisciplinary effort. In total, the ESPC clinic managed to solve the palliative issues in 81 of the 134 (60%) referred patients without involving the SPC team. However, later on an additional 29 (36%) of the 81 patients initially finished from the ESPC clinic developed complex palliative symptoms and were referred to a SPC team. illustrates the results of the survey among the oncologic staff members. Fourteen physicians and 34 nurses completed the survey. The majority of the staff gave the ESPC clinic very high scores. The survey demonstrated the clinic as helpful in the busy daily routines of the oncologic outpatient clinic, covering important issues of the patient’s complaints.

Figure 1. Survival estimate of patient population in the ESPC clinic compared to patient population in the SPC team.

Table 3. Interventions in the ESPC clinic.

Table 4. Survey of the staff.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that implementation of early palliative care significantly improves quality of life and reduces symptom burden in patients with advanced cancer [Citation1,Citation14] which was one of the main reasons for introducing the ESPC outpatient clinic. As described in the results section, to assess symptom burden, we asked patients to fill out the EORTC qlq-c30 pall prior to their visit in the clinic. Results demonstrated that the majority of patients referred to the ESPC clinic reported an inferior quality of life of a median of 3.4. This illustrated that there was a huge need for intervention. In several cases, patients expressed gratitude when finishing the consultation, appreciating someone taking the time to show interest in not merely their diagnosis, but in them as a person, their lives and their loved ones. Our results also showed the most prominent demand was for improvement of pain management, improved treatment of constipation, as well as management of psychological and existential pain. These findings are concordant with the results of Skjoedt et al. [Citation15]. One could argue that symptoms as pain and constipation ought to be handled by the oncologic staff. However, in a busy daily routine, focus of the dialogue is usually on treatment options concerning the oncologic diagnosis, possible effects and side effects to this treatment, prognosis and other oncologic issues. This might have the consequence that dialogue about other symptoms is not prioritized as highly, but this is merely an assumption. It could also be speculated, that the busy atmosphere in the outpatient clinic, may lead to many patients wishing to avoid bothering the staff with their basic complaints. Patients might also fear that their treatment possibilities will be reduced, if they present too many complaints, which might bias the symptoms reported to the oncologist. We believe that patients might have fewer reservations in the ESPC consultation, as focus of the dialogue is different, and the aim is an improvement of symptom burden and QoL, and not a matter of receiving treatment or not. Hence, as the oncologists manage the oncologic challenges, the ESPC staff can concentrate on patient reported symptoms, and how their disease affects their daily lives, rather than on diagnosis, disease stage and status. This opens up the possibility to touch subjects of a more personal character, as there is also time and sentiment for asking about psychological and existential challenges for the patients and their relatives. Results showed that most of our patients were terminated from the ESPC clinic after the initial contact and only one follow up visit. As we have only terminated patients, after either solving the issues they were referred with, or by referring them to our SPC unit, this illustrates that patients were screened effectively in the EPSC clinic. Patients with complex issues, and a need for a more intense follow up course, were quickly referred to the SPC clinic, and those with more basic palliative care issues, were followed up and finished in the ESPC clinic, demonstrating a rational use of resources in the clinic. Some of the complex patients, primary younger patients, who were assessed in the ESPC clinic had been offered a referral to the SPC unit prior to the visit in the ESPC clinic, but had declined due to the stigmatization of being a patient connected to a SPC unit. During the consultation in the ESPC clinic we were able to explain to these patients the benefits of being referred, which made them accept referral. Therefore, the ESPC clinic might also serve as a catalyst for early referral to SPC in patients with a complex symptom burden and reservations toward receiving SPC. Furthermore, the ESPC clinic also acts as a filter, where differentiation of non-complex versus complex patients is performed effectively and with a high level of expertise. Based on the above, we conclude that with our ESPC clinic, we were able to make a difference in many patient’s daily challenges with a relatively low effort, and hence also low costs for the health system. The Danish Palliative database [Citation13] have set a goal of no more than 10 days waiting time, from referral to a SPC unit, to primary contact. Our waiting times from referral to the first contact in the ESPC clinic did not meet this criterion. This illustrates the high need of a palliative effort in palliative oncologic patients, and that the ESPC clinic has filled a gap in treating and handling palliative care needs of our oncologic patients, though more available slots could be desired to bring down waiting times. We already determined that the ESPC clinic has benefited the palliative oncologic patients. We also wanted to determine satisfaction with the clinic among the staff in the oncologic outpatient clinic, and hence conducted a questionnaire survey among doctors and nurses in the clinic. Evaluation by the staff in the oncologic outpatient clinic revealed a high level of satisfaction with the ESPC clinic. We learned that the implementation process could have been even better by more intensive introduction to the staff. It was expressed that clarification of the referral criteria in addition to the oral and written information about the ESPC clinic would be beneficial. After completion of the survey, we made oral presentations of some of our data at the respective staff meetings with the purpose of accommodating the wishes from the staff. We specified in detail which patients might profit from assessment in the ESPC clinic and which interdisciplinary skills are not available there, but in the SPC unit. We believe that this specification will increase the referral rate, and that repeating this regularly would be beneficial. As mentioned by Kaasa et al. the achievement of integration among the different services and levels of health care is by no means straightforward. Although it has been known for years that integration of an early palliative approach at least results in better quality of life for oncologic patients [Citation7,Citation14] and several studies demonstrated a lesser consumption of health care services [Citation16] this process has not to our knowledge been implemented as a routine at the oncologic departments in Denmark. Whether the reason for this might be economic limitations is unknown. We have not made any cost – benefit analyses in our implementation process. Possible hurdles for implementation of ESPC might be the meeting of two different cultures with different foci—i.e., the tumor-centered and patient-centered pathways. These two cultures need to join forces and attend to the patient’s needs during the development and implementation of the ESCPs. The development of ESPC teams is a method for meeting these challenges [Citation1]. In the future, we aim to conduct follow up EORTC-questionnaires, to better evaluate the effect of our effort, including improvements in QoL. Furthermore, we are currently working on an electronic solution for the EORTC 30 questionnaire; which will hopefully make it easier for the patient to fill out the EORTC 30, and we will be able to automatically send out follow up questionnaires. Our next area of development will be expanding the staff composition to also include family team employees (psychologists and social workers) to our ESPC clinic, as these psychosocial family related problems were prominent in many of our patients and we think that many of them can be handled in an outpatient setting. It is not our intention to phase out the home visits, as these provide a completely different insight into the family composition. However, if some of the consultations took place in the ESPC clinic, one would be able to work with the issues earlier in the process and thus perhaps be able to resolve challenges for the families earlier on. Moreover, it would save time resources, which would benefit other patients. In addition, it is our long term aim that the participating oncologic nurses of the ESPC clinic will be able to undertake some of the follow-up visits, which are currently carried out by the doctors from the specialized palliative care unit. This could free up more ‘doctor consultation sessions’ and thus provide more patients the opportunity for ESPC. Unfortunately, we did not conduct a follow up survey after 1–4 weeks, as is standard with other patients in the palliative unit. Hence, we cannot demonstrate an effect of the effort in the ESPC clinic. However, to the best of our knowledge, and based on the oral feedback we have received from patients and their relatives, we are convinced that we were able to help most of our patients with reducing their symptom burden.

Ethics

As the study was conducted as a quality assurance study, only approval from Odense University Hospital was necessary and the approval was granted. The project was approved by with the Danish title: ‘Tidlig palliativ indsats hos uhelbredeligt syge kræftpatienter i et onkologisk forløb’ = ‘Early palliative approach in incurable cancer patients during an oncologic course’ as a quality assurance project. All patients gave written and oral informed consent.

Conclusion

This work describes our first year experiences after implementing an ESPC clinic in our Oncologic Department. Out of 101 admitted patients, we could solve the palliative needs for 81 patients after one or a few consultations. The most frequent palliative needs were pain, constipation and psychological needs. A survey at the oncologic staff showed large satisfaction with this new initiative, which hopefully in the future will expand, so more patients with complex palliative needs may have consultations in the clinic.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Katrine R Schønnemann, Sabine UA Gill and Stine Hollegaard. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sabine U Gill and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the enthusiastic contribution of our oncologic nurses Anja Ranum Broenserud, Christina Lykke Buhl, Mette Adelgaard, Ida Oerum Vestergaard, Helle Lyzet Hansen and Susanne Sejersen during the implementation process. Furthermore, we would like to thank the two reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback in the publication process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–e653.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730.

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749.

- Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):99–121.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients With lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834–841.

- Riolfi M, Buja A, Zanardo C, et al. Effectiveness of palliative home-care services in reducing hospital admissions and determinants of hospitalization for terminally ill patients followed up by a palliative home-care team: a retros. Palliat Med. 2014;28(5):403–411.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742.

- Woldie I, Elfiki T, Kulkarni S, et al. Chemotherapy during the last 30 days of life and the role of palliative care referral, a single center experience. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):20.

- Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, et al. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: a cluster randomised trail. Lancet. 2000;356(9233):888–893.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats. [Anbefaling] København S, Danmark: s.n., 05. Dec 2017.

- Langan SM, Schmidt SAJ, Wing K, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ 2018;363:k3532.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The Europen organisation for research end treatent of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Bang Hansen M, Adsersen M, Grønvold M. Dansk palliativ database: Årsrapport 2021. København. Aarhus: Regionernes Kliniske Kvalitetsudviklingsprogram; 2022.

- Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD011129.

- Skjoedt N, Johnsen AT, Sjøgren P, et al. Early specialised palliative care: interventions, symptoms, problems. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11(4):444–453.

- Bandieri E, Banchelli F, Artioli F, et al. Early versus delayed palliative/supportive care in advenced cancer: an observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(4):e32–e32.