Abstract

Background

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15% of lung cancer and is associated with poor prognosis. In platinum-refractory or -resistant SCLC patients, few treatment options are available. Topotecan is one of the standards of care for these patients, however, due to its high toxicity, several different approaches are employed. FOLFIRI (folinate, 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) is a chemotherapy regimen used in digestive neuroendocrine carcinoma, which shares pathological similarities with SCLC. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of FOLFIRI in patients with platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC.

Methods

Medical records from all consecutive SCLC patients treated with FOLFIRI in a French University Hospital from 2013 to 2021 were analyzed retrospectively. The primary endpoint was the objective response rate according to RECIST v1.1 or EORTC criteria (ORR); secondary endpoints included duration of response, disease control rate, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and safety profile.

Results

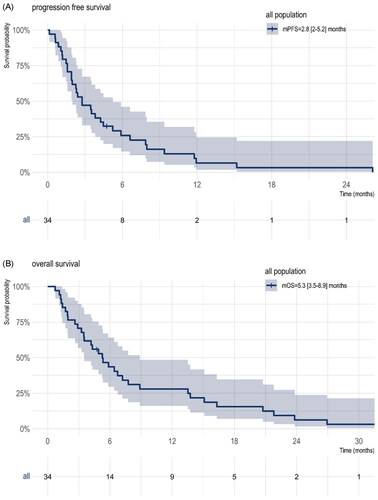

Thirty-four patients with metastatic platinum-resistant (n = 14) or -refractory (n = 20) SCLC were included. Twenty-eight were evaluable for response, with a partial response observed in 5 patients for an overall ORR in the evaluable population of 17.9% (5/28) and 14.7% (5/34) in the overall population. The disease control rate was 50% (14/28) in the evaluable population. The median PFS and OS were 2.8 months (95%CI, 2.0–5.2 months) and 5.3 months (95%CI, 3.5–8.9 months), respectively. All patients were included in the safety analysis. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 13 (38.2%) patients. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were asthenia, neutropenia, thrombopenia and diarrhea. There was no adverse event leading to discontinuation or death.

Conclusion

FOLFIRI showed some activity for platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC in terms of overall response and had an acceptable safety profile. However, caution is needed in interpreting this result. FOLFIRI could represent a potential new treatment for platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC patients. Further prospective studies are needed to assess the benefits of this chemotherapy regimen.

FOLFIRI showed some activity for platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC in terms of overall response.

FOLFIRI was well-tolerated in platinum resistant/refractory SLCL patients.

FOLFIRI could represent a potential new treatment for SCLC, prospective studies are needed.

HIGHLIGHTS

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [Citation1]. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15% of lung cancer and is associated with poor prognosis [Citation2]. Immunotherapies and targeted therapies have been a breakthrough in patients’ care with non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLC) [Citation3–6]. However, no major progress has been made in the last 30 years in the management of advanced SCLC, and platinum-etoposide regimens remain the cornerstone of treatment [Citation7]. Recently, the addition of immunotherapies atezolizumab or durvalumab (PD-L1 blockade) to platinum-etoposide first-line chemotherapy in phase III clinical trials IMpower 133 and CASPIAN resulted in a significant but modest improvement in overall survival (OS) [Citation8,Citation9].

Although SCLC is highly sensitive to chemotherapy, most patients relapse within the first six months. Second-line therapy depends on the treatment-free interval (TFI) and response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy [Citation7]. Platinum-etoposide rechallenge for platinum-sensitive SCLC (i.e., TFI≥ 3 months) is associated with a high objective response rate (ORR = 49%) and better clinical outcomes than subsequent chemotherapy [Citation10]. In platinum-refractory (i.e., cancer progressing during platinum-based chemotherapy) and -resistant (i.e., TFI <3 months) cancer, outcomes are poor, and the clinical benefit of further systemic therapy is highly uncertain. In this setting, ORR to second-line chemotherapy is about 15% [Citation7]. Topotecan proved to significantly increase OS compared to the best supportive care and represents one of the standards of care in this setting [Citation11]. However, topotecan use is challenging because of its association with severe and frequent haematological toxicities and limited clinical benefit [Citation12]. Compared to topotecan amrubicin showed a modest improvement in OS in a subset of platinum-refractory patients (HR = 0.77, p = 0.047) in a phase III randomized trial and represents another standard of care for this population [Citation13]. The anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen: CAV (Cyclophosphamide-Adriamycin-Vincristine) showed similar efficacy compared to topotecan in a phase III randomized trial [Citation14]. Recently, lurbinectedin has shown an ORR of 22.2% in second-line treatment for platinum-resistant SCLC [Citation15], but its association with doxorubicin failed to improve OS compared to topotecan [Citation16]. More recently, several novel therapeutic strategies in the second-line setting, such as rovalpituzumab-tesirine [Citation17], nivolumab [Citation18], and nivolumab-ipilimumab [Citation19] have not improved outcomes. There is, therefore, an unmet need for effective and well tolerated treatment options.

The type 1 topoisomerase inhibitor irinotecan monotherapy has been evaluated in relapsed SCLC on 16 patients in a phase II study which found an ORR of 47% and a median OS of 187 days [Citation20]. Furthermore, it has been assessed in combination with platinum versus platinum-etoposide for platinum-sensitive SCLC with comparable clinical outcomes [Citation21–23] and is used in several institutions instead of etoposide in the platinum chemotherapy combination in first-line setting. Irinotecan is associated with less severe anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia than topotecan but with more digestive toxicities with frequent diarrheas as well as nausea and vomiting, which can be managed with supportive care.

FOLFIRI (folinate, 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) is a widely used chemotherapy regimen, especially in digestive cancers [Citation24]. FOLFIRI has also been effective in treating high-grade digestive neuroendocrine carcinoma, which shares pathological similarities with SCLC [Citation25–27]. FOLFIRI has never been assessed in advanced SCLC, but the synergic activity between 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan could be promising in advanced SCLC.

We propose herein to report our local experience of FOLFIRI use in pretreated SCLC. We aimed to assess the clinical benefit and the safety profile of FOLFIRI in platinum-resistant/refractory advanced SCLC patients from the Medical Oncology Department of Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), France.

Material and methods

Study design and patients

Data were retrospectively collected from all consecutive patients with SCLC who received FOLFIRI during an eight-year period, from 2013 to 2021 in the Medical Oncology department of the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, a University Hospital in Paris, France. Patients with a histologically confirmed SCLC treated with FOLFIRI were considered for inclusion. Other eligibility criteria were: ≥18-year-old, at least one prior platinum-based chemotherapy line, platinum-resistant (<3 months after platinum discontinuation) or -refractory (during platinum-based chemotherapy) tumor progression, and at least one fully administered cycle of FOLFIRI. Patients with a concomitant treatment for another neoplasm were excluded.

Study treatment

Irinotecan was administered intravenously on day 1 at a dose of 180 mg/m2, and 5-fluorouracil was administered on days 1–2 by continuous infusion over 44 h at the dose of 2400 mg/m2 of a 14-day cycle. Treatment was discontinued upon disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, altered performance status (PS), or physician decision.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the radiological or metabolic response rate according to Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) [Citation28] or European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria [Citation29]. Secondary endpoints were the duration of response, disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), OS and safety profile. The median duration of response was defined as the time between initiation of FOLFIRI treatment and disease progression (RECIST or not-RECIST progressive disease) for patients who achieved an objective response. PFS was defined as the time between introducing FOLFIRI and disease progression (RECIST or not-RECIST progressive disease) or death. OS was defined as the time between introducing FOLFIRI and death. For the safety evaluation, adverse events were retrospectively collected and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0. Given the retrospective nature of the study, we limited our collection of adverse event data to only those events that were classified as serious (CTCAE grade >2) or resulted in a dose reduction or interruption of treatment.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistical analysis involved calculating the median and interquartile range for each quantitative parameter, as well as the number of missing values. The progression-free survival (PFS) the overall survival (OS) and the follow-up time data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier curves. The follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.1.3). To determine the median PFS, OS and follow-up and their corresponding confidence intervals, we used the R "survminer" package.

Ethics statement

All living patients received written information and provided their oral consent for data collection. Patients’ clinical charts were retrospectively collected from electronic files using a de-identified form. This study was approved by the Inserm Ethics Evaluation Committee (CEEI) on 6 December 2022: 22-973.

Results

Patient characteristics

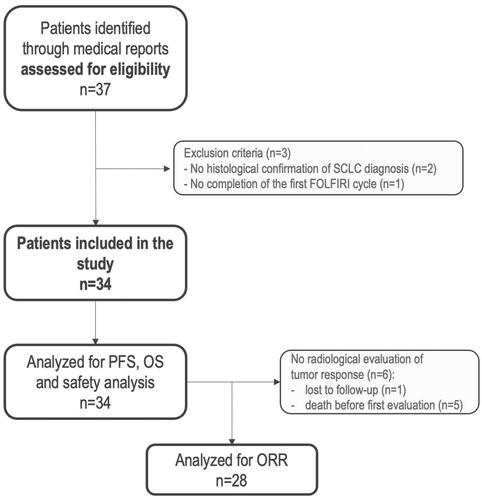

Between March 2013 and November 2021, a total of thirty-seven patients were identified through the local database. Three patients did not meet inclusion criteria (no histological diagnosis of SCLC (n = 2), did not receive a complete cycle of FOLFIRI (n = 1)) and were excluded (Flow chart ) for a total of thirty-four patients included. Median follow-up was not reached (Supplementary Figure 1). Only one patient was lost to follow-up, and all other patients except one had died at the time of data collection.

Figure 1. Flow chart. SCLC: small-cell lung cancer; FOLFIRI: 5fluorouracile irinotecan; PFS: progression free-survival; OS: overall survival; ORR: objective response rate.

The patient characteristics are listed in . The median age was 63 years (range from 45 to 84), 23/34 (67.6%) patients were male, 24/34 (70.6%) presented an ECOG PS of 1 and 10/34 (29.4%) of ≥2, 6/34 (17.6%) experienced tumor recurrence after initial locoregional treatment, and 17/34 (50%) patients presented central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Before FOLFIRI initiation, 19/34 (55.9%) patients received only 4–6 cycles of platinum-etoposide, 11/34 (32.4%) were rechallenged with platinum-etoposide (10 one rechallenge and 1 two rechallenges), 1/34 (2.9%) received platinum-etoposide followed by paclitaxel, and 1/34 (2.9%) received platinum-etoposide then topotecan then adriamycin-cyclophosphamide (). At the time of FOLFIRI initiation, 14/34 (41.2%) were considered platinum-resistant and 20/34 (58.8%) platinum-refractory ().

Table 1. Patients baseline characteristics.

Efficacity

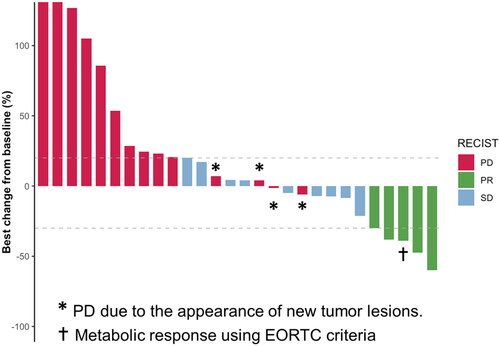

Among the thirty-four patients, twenty-seven had a CT-scan evaluation and measurable tumor lesion according to RECIST 1.1 criteria. One patient had a PET-scan evaluation with a measurable tumor lesion according to EORTC criteria. The median time from the first administration of FOLFIRI to the radiological tumor nadir CT scan was 73 days (IQR: 49 days). Six patients had no radiological evaluation on treatment available: one was lost to follow-up and five died before the first evaluation: 2 from hypoxemic infectious pneumonia with decompensation of chronic illness (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic heart failure) and without chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, 2 from clinical tumor progression and 1 from unknown cause. The ORR is shown in . Four patients obtained a partial response according to RECIST 1.1 criteria and one according to EORTC criteria for an overall ORR of 17.9% (5/28) in the evaluable population and 14.7% (5/34) in the overall population. Among the evaluable population, the ORR in the platinum-resistant group was 30.0% (3/10) and 11.1% (2/18) in the platinum-refractory group (). The median duration of response was 40.1 weeks (IQR 34.6–52) among the 5 patients who exhibited objective responses. The DCR was 50% in the evaluable population (Waterfall plot ). The median PFS and OS were 2.8 months (95%CI, 2.0–5.2 months)((A)) and 5.3 months (95%CI, 3.5–8.9 months) ((B)), respectively.

Figure 2. Waterfall plot of radiological objective response. RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors version 1.1; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Table 2. Analysis of tumor response.

Safety

All patients were included in the safety analysis (). Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 13/34 (38.2%) patients. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were asthenia, neutropenia, thrombopenia and diarrhea. Adverse events led to dose reductions in 11/34 (32.4%) patients. Five (45.5%) of these dose reductions were due to hematotoxicity. There was no adverse event leading to discontinuation or death. It should be noted that two patients died approximately one month after their first cycle of FOLFIRI due to respiratory infections, which led to the decompensation of their preexisting chronic conditions (COPD and chronic heart failure). We evaluated these deaths as not being directly related to the chemotherapy, as they did not experience chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.

Table 3. Safety profile.

Discussion

This retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and the safety profile of the FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimen in platinum-resistant or -refractory SCLC. In this cohort of thirty-four unselected patients, FOLFIRI showed some activity for platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC in terms of ORR and DCR and presented an acceptable safety profile in this frail population.

Of note, topotecan is the only drug that has demonstrated an improvement in OS versus best supportive care (median 25.9 versus 13.9 weeks) in the second-line setting of patients with SCLC in phase III randomized trial [Citation11]. A study analyzing topotecan in relapse platinum-sensitive SCLC compared to CAV showed a similar ORR and OS within the two treatment arms [Citation14]. In this setting, lurbinectedin recently showed an encouraging ORR in a phase II trial [Citation14], but its association with doxorubicin failed to improve OS compared to topotecan [Citation16]. Several phase II trials evaluating single chemotherapy regimens in SCLC second-line setting showed interesting but highly heterogeneous clinical efficacy [Citation30–32]. However, these studies included platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant SCLC patients. In a recent meta-analysis by N. Horita evaluating 1347 patients with relapse SLCL treated with topotecan, the ORR in platinum-sensitive patients was 17% but dropped to 5% for platinum-resistant/refractory patients [Citation33].

Like topotecan, irinotecan is a type 1 topoisomerase inhibitor but has a more manageable safety profile. Its synergic activity with 5-fluorouracil has led to the routine use and development of the FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimen, especially in digestive cancers [Citation24]. SCLC is the most frequent neuroendocrine lung tumor and shares pathological and molecular similarities with extrapulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas [Citation34]. FOLFIRI is one of the preferred treatment options as a second-line in patients with digestive advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma after failure of the etoposide–platinum combination [Citation27, Citation35]. This led our center to adopt FOLFIRI as the preferred treatment option for platinum-resistant/refractory advanced SCLC patients in routine clinical practice.

This retrospective study included unselected patients with several poor prognostic factors, such as poor general condition (29.4% PS ≥ 2), CNS metastases (50%) and platinum-refractory tumor progression (58.8%). Despite those features, FOLFIRI showed some activity for platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC with a 50% of disease control rate and an encouraging ORR of 17.9% in the evaluable population. The overall response results are supported by the durability of responses, with a median duration of response of 40.1 weeks. The median PFS was 2.8 months, and the median OS 5.3 months, which is noteworthy in the platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC setting. Of note, in platinum-resistant SCLC evaluable patients, the ORR achieved 30%. Furthermore, the safety profile was acceptable and similar to previous trials assessing this FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimen. We found significant toxic digestive and hematologic effects, but these adverse events were manageable, and there was no treatment-related death or discontinuation.

Our study has several limitations, most of which relate to its retrospective and single-center nature. Only twenty-eight patients were evaluable for objective radiological or metabolic tumor response. We used two different methods to evaluate tumor responses: RECIST and EORTC. The interpretation of the results is further limited by the variability of the interval between the first administration of FOLFIRI and the radiological tumor nadir CT scan, which had a median of 73 days (IQR= 49 days). Considerable heterogeneity between patients was also observed in terms of prior chemotherapy regimens administered. Considering the heterogeneity of the patient population and the use of different prior treatment regimens suggest that the study sample may not be representative of a typical SCLC patient. The choice of the primary endpoint (ORR) is a matter of debate. It is worth noting that ORR is a commonly used surrogate endpoint for anticancer activity in early-phase trials, and our results suggest that this treatment approach may have promise in this patient population. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the limitations of our study, and further prospective and comparative studies are needed to evaluate the potential of this treatment approach.

Irinotecan has been shown to be effective in treating SCLC [Citation20–23]. Therefore, the observed antitumor effect may be solely attributed to Irinotecan, and the contribution of adding 5FU to the treatment is uncertain. Furthermore, it is important to note that the safety profile observed in this study may not be applicable to the entire population of SCLC patients, especially those of Asian origin.

To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the clinical benefit of FOLFIRI in advanced platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC patients. Our analysis suggests that FOLFIRI might be effective in this setting with an acceptable safety profile. FOLFIRI could represent a potential new treatment for patients with platinum-resistant/refractory SCLC. Further prospective studies are needed to assess the benefits of this chemotherapy regimen in this setting. A phase II clinical trial evaluating FOLFIRI in platinum-resistant/refractory advanced SCLC patients is currently under development at our center.

Ethics statement

All living patients received written information and provided their oral consent for data collection. Patients’ clinical charts were retrospectively collected from electronic files using a de-identified form. This study was approved by the Inserm Ethics Evaluation Committee (CEEI) on December 6th 2022: 22-973.

Author contributions

Roussel-Simonin Cyril: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Visualization; Writing original draft; Writing review & editing.

Gougis Paul and Lassoued Donia: Formal analysis; Data curation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing review & editing.

Vozy Aurore, Veyri Marianne, Morardet Laetitia, Wassermann Johanna, Foka Tichoue Hervé, Jaffrelot Loïc, Hassani Lamia, Perrier Alexandre, Bergeret Sebastien, Taillade Laurent, Spano Jean-Philippe: Resources; Writing review & editing.

Campedel Luca: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing review & editing.

Abbar Baptiste: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing review & editing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [BA], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249.

- Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):3.

- Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):829–838.

- Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–125.

- Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639.

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833.

- Dingemans AMC, Früh M, Ardizzoni A, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(7):839–853.

- Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-Cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2220–2229.

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum–etoposide versus platinum–etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1929–1939.

- Baize N, Monnet I, Greillier L, et al. Carboplatin plus etoposide versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1224–1233.

- O'Brien MER, Ciuleanu T-E, Tsekov H, et al. Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed Small-Cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(34):5441–5447.

- Eckardt JR, von Pawel J, Pujol JL, et al. Phase III study of oral compared with intravenous topotecan as second-line therapy in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):2086–2092.

- Von Pawel J, Jotte R, Spigel DR, et al. Randomized phase III trial of amrubicin versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):4012–4019.

- Von Pawel J, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, et al. Topotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(2):658–667.

- Trigo J, Subbiah V, Besse B, et al. Lurbinectedin as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):645–654.

- Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu T, Navarro A, et al. PL02.03 lurbinectedin/doxorubicin versus CAV or topotecan in relapsed SCLC patients: phase III randomized ATLANTIS trial. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2021;16(10):S844–S845.

- Uprety D, Remon J, Adjei AA. All that glitters is not gold: the story of rovalpituzumab tesirine in SCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(9):1429–1433.

- Spigel DR, Vicente D, Ciuleanu TE, et al. Second-line nivolumab in relapsed small-cell lung cancer: checkMate 331⋆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):631–641.

- Owonikoko TK, Park K, Govindan R, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab as maintenance therapy in extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: checkMate 451. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(12):1349–1359.

- Masuda N, Fukuoka M, Kusunoki Y, et al. CPT-11: a new derivative of camptothecin for the treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(8):1225–1229.

- Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):85–91.

- Hanna N, Bunn PA, Langer C, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2038–2043.

- Lara PN, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2530–2535.

- Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1386–1422.

- Bardasi C, Spallanzani A, Benatti S, et al. Irinotecan-based chemotherapy in extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas: survival and safety data from a multicentric Italian experience. Endocrine. 2021;74(3):707–713.

- Sugiyama K, Shiraishi K, Sato M, et al. Salvage chemotherapy by FOLFIRI regimen for poorly differentiated gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2021;52(3):947–951.

- Hentic O, Hammel P, Couvelard A, et al. FOLFIRI regimen: an effective second-line chemotherapy after failure of etoposide-platinum combination in patients with neuroendocrine carcinomas grade 3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19(6):751–757.

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247.

- Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC) PET study group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(13):1773–1782.

- Yamamoto N, Tsurutani J, Yoshimura N, et al. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel for relapsed and refractory small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(1B):777–781.

- Masters GA, Declerck L, Blanke C, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine in refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer: eastern cooperative oncology group trial 1597. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(8):1550–1555.

- Zugazagoitia J, Paz-Ares L. Extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: first-line and second-line treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6):671–680.

- Horita N, Yamamoto M, Sato T, et al. Topotecan for relapsed small-cell lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of 1347 patients. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):15437.

- Oronsky B, Ma PC, Morgensztern D, et al. Nothing but NET: a review of neuroendocrine tumors and carcinomas. Neoplasia. 2017;19(12):991–1002.

- L de M, Lepage C, Baudin E, et al. Digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN): french intergroup clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (SNFGE, GTE, RENATEN, TENPATH, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, SFR). Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(5):473–492.