Abstract

Aim

The aim of this descriptive study is to analyze the cost for the treatment of NSCLC and SCLC patients (2014–2019) in Finland. The primary objective is to understand recent (2014–2019) cost developments.

Methods

The study is retrospective and based on hospital register data. The study population consists of NSCLC and SCLC patients diagnosed in four out of the five Finnish university hospitals. The final sample included 4047 NSCLC patients and 766 SCLC patients.

Results

Cost of the treatment in lung cancer is increasing. Both the average cost of the first 12 months as well as the first 24 months after diagnosis increases over time. For patients diagnosed in 2014, the average cost of the first 24 months was 19,000 €and for those diagnosed in 2015 22,000 €. The annual increase in the nominal 24-month costs was 10.4% for NSCLC and 7.3% for SCLC patients.

Conclusion

The average cost per patient has increased annually for both NSCLC and SCLC. Possible explanations to the cost increase are increased medicine costs (especially in NSCLC), and the increased percentage of patients being actively treated.

Introduction

Lung cancer has been responsible for 8% of cancer-related healthcare costs in EU countries [Citation1]. Costs per lung cancer patient varies between studies and countries and can depend on the methodology of the study, costs that are considered, and the healthcare system in the countries. In the UK, the total cost of treatment of lung cancer patients is estimated to be around £25,000 [Citation2] while in Finland in 2014 it was estimated to €29,100 per patient over the whole treatment period [Citation3]. In the USA, the treatment cost for the first 12 months is reported to be $35,000 and as high as $52,000 for the last 12 months of life [Citation4]. Although it is thus difficult to make international comparisons of costs the trend of costs over time can be analyzed to further understand recent cost developments.

Several novel drugs have been introduced for lung cancer during the study period ([Citation5–9]). Especially, in high income countries, the current treatment guidelines are under pressure as new innovative treatments promote drugs for a larger portion of patients than before [Citation10,Citation11].

However, there is little evidence of whether and how the new treatment options have an influence on time on treatment and the total cost of treatment as Nicolson [Citation12] suggests. Especially, with increasing strain on public finances in developed countries [Citation13], it is important to understand the effect of the recent development of new treatments on costs [Citation14,Citation15]. It is not enough to examine only the cost of direct oncological treatments, but to analyze the healthcare cost more comprehensively, including all the service usage due to disease itself, treatment complications and adverse events [Citation16–18].

The aim of this descriptive study is to analyze recent (2014–2019) trends in cost of the treatment of NSCLC and SCLC patients in Finland. The Finnish healthcare system offers good opportunities for real-world data (RWD) as electronic medical records are in use in each hospital, recording of treatments is standardized and structured and every event can be linked to the patient by a unique personal identity code.

In this study, we analyze the trends in treatment costs per patient for lung cancer patients in Finland from 2014 to 2019 (diagnosed 2014–2018). The primary objective is to understand the cost developments.

Materials and methods

The study is retrospective and based on hospital register data. The study population consists of NSCLC and SCLC patients diagnosed in four out of the five Finnish university hospitals: Helsinki University Hospital (HYKS), Tampere University Hospital (TAYS), Kuopio University Hospital (KYS) and Turku University Hospital (TYKS), between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2018. In 2018, the populations of these four university hospital districts covered 53% of the Finnish population. The inclusion criteria are: an NSCLC diagnosis (ICD-10 codes C34.X1-5) or SCLC diagnosis (ICD-10 codes C34.X6-7) recorded between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2018 and municipality of residence in the hospital district of the caring university hospital. The study is restricted to adult (age > = 18) patients at diagnosis. The final sample included 4047 NSCLC patients and 766 SCLC patients. The study cohort included patients taking part in clinical trials.

Data were gathered from hospital information systems (electronic medical records EMR, and the pharmacy information system). Both structured and unstructured data were used. All events and episodes were linked to the patient based on a personal identity code. The structured EMR data includes data on inpatient days, surgical procedures, emergency department visits, physician and nurse visits and consultation over phone, diagnostics, prescriptions, radiotherapy visits, as well as gender, age and municipality of residence. Each visit or inpatient episode includes information on the date, diagnosis, clinic, speciality and possible procedures. The structured hospital pharmacy data included dates of administration and drugs (ATC codes) for all medicines administered in the hospital to each patient in the study population. Data on prescriptions for outpatient medicines was collected separately from hospital information systems.

Cancer stage and performance status of the patient at the time of diagnosis were retrieved from unstructured medical report data with keywords (Supplementary Appendix B for the list of used keywords). An algorithm was used to classify the search results for stage into categories I, II, III and IV, and for performance status into ECOG categories of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The classifications were validated by a clinician. Both the stage and performance status at the time of diagnosis were identified based on the closest input date to the lung cancer diagnosis date per patient. The maximum date difference being ± 60 days.

The treatments analyzed were surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, IO treatment, targeted therapies, other biological treatments and other cancer medication. See Supplementary Appendix C for the list of treatment profiles included in the study. The patients were grouped based on the profile of treatments they received into mutually exclusive groups: IO treatment, (defined as having received IO treatment regardless of what other treatment the patient has received), targeted therapy (defined as having received targeted therapy regardless of what other treatment the patient has received, excluding IO treatment), chemotherapy only, chemotherapy and surgery, surgery only, radiotherapy only, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, other, and palliative treatment (including palliative radiotherapy). The category ‘Other’ includes all treatment profiles that are not included in the previous categories. All costs for treatment of each patient in the study cohort are included in the cost analysis, regardless of which treatment profile the patient was in.

The costs components for treatment of lung cancer in this study are: outpatient care, inpatient care and medicines. The cost per patient was calculated based on the number of outpatient visits, the number and length of inpatient care periods and the number doses and prescriptions of medicines that the patient received between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2019, starting from 60 days prior to the patient’s time of diagnosis. The starting point of cost incurrence was defined to be 60 days before the actual time of diagnosis, in order to take into account possible differences between hospitals regarding the entering of diagnosis information into patient records. Medicine costs and surgery cost were retrieved as actual unite cost and the episode and visit cost were calculated as average cancer care costs for university hospitals in Finland. All outpatient and inpatient care received by the patient was included in the costs, regardless of whether the primary diagnosis related to the event was lung cancer. This was because recording practices e.g., regarding the treatment of complications differ between hospital and specialists. According to clinical experts, lung cancer patients undergoing cancer treatments are seldom treated for conditions entirely unrelated to lung cancer and there is only a minor risk that other non-lung cancer related cost would be included. Medicines administered in the hospital and prescriptions prescribed on the basis of the patient’s lung cancer diagnosis were included in the cost calculations. All costs are considered in 12-month intervals.

Outpatient care costs were calculated based on the number of outpatient visits per patient. The costs of outpatient visit and other (non-surgery-related) inpatient episodes were calculated based on average unit costs for outpatient visits and inpatient days in pulmonology clinics in university hospitals in Finland. The applied unit costs (adjusted to the 2019 price level) per visit were equal to the average costs in Finnish university hospitals reported by the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare [Citation18] adjusted for inflation. The costs of outpatient visit and other (non-surgery-related) inpatient episodes were calculated based on average unit costs for outpatient visits and inpatient days in pulmonology clinics in university hospitals in Finland. The unit cost reflects the average cost of visits or inpatient days include e.g., personnel, materials, diagnostics and facilities.

Outpatient visits were assigned three different unit costs based on the type of visit and the speciality assigned to the visit. Planned lung cancer-related outpatient visits, e.g., radiotherapy, were assigned the cost of non-emergency lung disease visits (296€). Emergency visits were assigned the average cost of emergency visits (393€). Other visits, which were not related to lung cancer based on the speciality, were assigned the average cost of non-emergency visits (328). Outpatient visits occurring physically in the hospital were assigned a unit cost. For example, phone calls between patients and medical staff were not included in the cost calculations, as the expenses incurred from these are included in the aforementioned costs of physical visits.

Inpatient care episodes were assigned a unit cost depending on whether the episode included surgery or not. The unit costs of inpatient care periods including surgery were determined based on the average cost of the episode’s DRG (diagnosis-related group) code in Finnish university hospitals [Citation19].

The cost of inpatient care periods not including surgery were calculated based on the length of the period in terms of days and the average cost per day of inpatient care in Finnish university hospitals [Citation18] adjusted for inflation (554€per day).

The costs of medicines administered in the hospital were estimated based on the number of doses per ATC code received by each patient (obtained from electronic medical records) and the unit cost of each ATC code (obtained from hospital pharmacy billing data). The medicine costs are patient specific (cost per dose times the number of doses for each patient) and obtained from the pharmacies. The unit cost per dose for each ATC code in hospital medicine data was calculated based on the average price of the given ATC code in university hospitals between 2014 and 2019 in the hospital pharmacy billing data. Costs incurred from medicines administered at home were estimated based on patients’ prescriptions and average cost per prescription for each ATC code obtained from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (Kela). In the Finnish healthcare system, the costs of medicines administered inside a hospital are covered by the hospital, while the costs of prescription medicines are covered by Kela. The cost data on prescription medicines includes those ATC codes for which the patient was granted a reimbursement on the basis of a lung cancer diagnosis (including all diagnoses beginning with C34). Overall, the costs of treatment are reported in 2019 prices, with the exception of costs of medicines administered in the hospital, the price of which is set as the average price per ATC code in university hospitals between 2014 and 2019. This is due to the substantial yearly fluctuation of the prices of these medicines.

Patients are grouped based on the year of diagnosis to form cohorts. This allows the analysis of changes in costs over time. Cost trend analysis is done based on costs incurred during the first 24 months of treatments to ensure comparability between different cohorts. The analysis for 24 months is conducted for patients diagnosed between 2014 and 2017. Patients diagnosed after 2017 have not all been in treatment for full 24 months because the study data ends on 31 December 2019. Average costs per patient grouped by stage or performance status at the time of diagnosis are reported only for NSCLC patients, because when grouped into the aforementioned smaller cohorts, the number of SCLC patients in the study population becomes too small to allow significant findings.

The statistical significance of trends and magnitude of increase in costs per patient was analyzed by linear regression models using the Python statsmodels package. If the estimated slope of the model differed from zero at the 0.05 level, the trend was significant.

Results

Patient demographics

The total population in the study is 4047 NSCLC patients and 766 SCLC patients. The number of patients diagnosed yearly in both patient groups remains fairly stable throughout the study period ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics by the year of diagnosis.

Amongst the NSCLC patients for whom data on the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis could be found from patient records (28% of the patients, n = 1133), 17% were identified as having stage I, 12% as stage II, 22% as stage III and 49% as stage IV. The patient’s performance status at the time of diagnosis could be defined for 30% of the NSCLC patient population (n = 1195). Amongst these, ECOG 1 represented the largest share of patients (47%). The second largest share of patients, 21%, were defined as ECOG 0. The remaining patients were defined as ECOG 2 (20%), ECOG 3 (10%) and ECOG 4 (2%).

Treatment costs

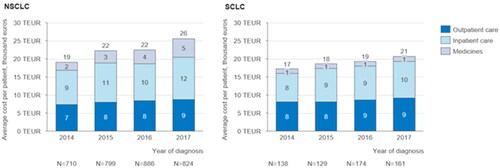

The treatment cost per patient for the first 24 months of treatment varies between 19,000€ and 26,000€ for NSCLC patients (, first panel) and between 17,000€ and 21,000€ for SCLC patients (, second panel) depending on the year of diagnosis. The average cost per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis increases for both NSCLC patients (slope: 1983; 95%CI: 203–3762; p = .041) and SCLC patients (slope: 1247; 95%CI: 636–1858; p = .013). On average, the largest cost category for both NSCLC and SCLC patients is inpatient care, which accounted for 47% of the costs per NSCLC patient and 49% of the costs per SCLC patient diagnosed in 2017. Costs per patient for the first 24 months increase fairly evenly for each cost category amongst NSCLC patients. The highest absolute increase between 2014 and 2017 is in cost component of medicine costs (slope: 889; 95%CI: 429–1350; p = .014), which increase from €2 000 amongst patients diagnosed in 2014 to €5000 amongst patients diagnosed in 2017. However, the increase in inpatient cost is almost as large. Amongst SCLC patients, the cost per patient for the 24 months increases mainly due to increase in inpatient care costs. This increase is, however, not statistically significant (slope: 685; 95%CI: 86–1455; p = .062).

Figure 1. Average cost (thousands of eur) per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis grouped by year of diagnosis: Average outpatient care, inpatient care and medicine costs per patient incurred during the first 24 months after the time of diagnosis, grouped by the year of diagnosis for NSCLC and SCLC patients.

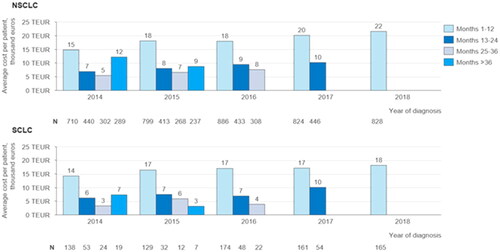

Amongst both NSCLC and SCLC patients, the largest share of costs is incurred during the first year after diagnosis (, first and second panel). There is a statistically significant increase in costs during the first 12 months of treatment for patients diagnosed between 2014 and 2018 for both NSCLC patients (slope: 1552; 95%CI: 694–2409; p = .01) and SCLC patients (slope: 841; 95%CI: 183–1499; p = .027). There is also an increase in costs during months 13 to 24 after diagnosis amongst NSCLS and SCLC patients, but this increase is only statistically significant for NSCLC patients (slope: 1120; 95%CI: 712–1527; p = .007). Second year costs are not yet available for patients diagnosed in 2018 or later. There is also a statistically significant increase in the average cost during months 25 to 36 for NSCLC patients (slope: 1083; 95%CI: 186–1980; p = .041). On average, first-, second- and third-year costs are higher for NSCLC patients than for SCLC patients.

Figure 2. Average yearly cost per patient after diagnosis grouped by year of diagnosis: Average cost per patient incurred during the first-, second- and third-year after the time of diagnosis, grouped by the year of diagnosis for NSCLC and SCLC patients. The average costs for months 13 to 24 and after include only patients receiving treatment during this time period.

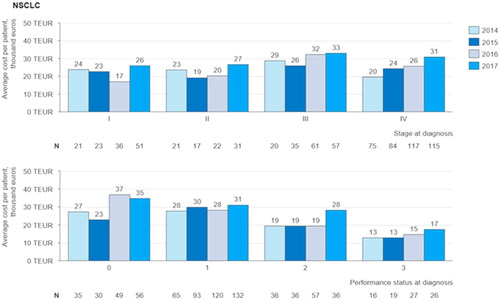

Figure 3. Average cost per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis grouped by stage and performance status at diagnosis and by year of diagnosis: Average total cost per patient incurred after the time of diagnosis, grouped by the stage of disease at the time of diagnosis, the patient’s performance status at the time of diagnosis, and by the year of diagnosis for NSCLC patients.

First 24 months after diagnosis, the average cost per patient increases over time (). The increase is statistically significant only for patients diagnosed at stage IV (slope: 3529; 95%CI: 1312–5745; p= .021), Amongst patients diagnosed during 2014 and 2017, stage III patients have the highest average cost per patient, varying from €26,000 in 2015 to €33,000 in 2017.

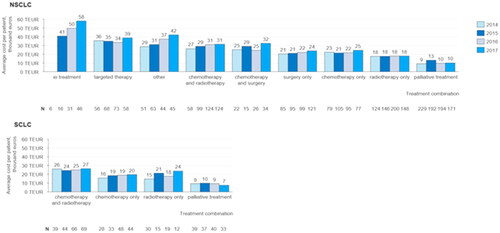

The average cost for the first 24 months after diagnosis for an NSCLC patient is between €9000and €58,000 depending on the year of diagnosis and the treatment profile of the patient (). The highest average costs per patient are amongst patients receiving IO treatments, ranging from €41,000 to €58,000, depending on the year of diagnosis. Costs for patients diagnosed in 2014 receiving IO treatment are not included, as the number of patients in this cohort is too small to allow comparison with the following years. Throughout the time period examined in the study total costs per patient were lowest for those patients receiving palliative treatment.

Figure 4. Average cost per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis grouped by treatment profile and by year of diagnosis: Average total cost per patient incurred during the first 24 months after the time of diagnosis, grouped by treatment profile and by year of diagnosis for NSCLC and SCLC patients.

The average cost for SCLC patients during the same time period varies between €7000 and €27,000. The costs per patient for SCLC patients are, on average, lower than those of NSCLC patients in the same treatment profile category, except for patients receiving only radiotherapy. For NSCLC patients there is a statistically significant positive trend in the average cost per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis in the treatment profile categories IO treatment (p = .012), Other (p = .014), Chemotherapy and radiotherapy (p = .049) and Surgery only (p = .010). Also, the average cost for the first 24 months for the entire NSCLC patient population increases between patients diagnosed in 2014 and 2017 (p = .044).

The average costs per patient grow between 2014 and 2017 for SCLC patients receiving chemotherapy and radiotherapy, chemotherapy only and radiotherapy only. However, the trend is not statistically significant.

The most common treatment profile amongst NSCLC patients diagnosed between 2014 and 2017 was no active oncological treatment, followed by radiotherapy only. However, the number of patients receiving no active oncological treatment (or only palliative radiotherapy) decreased during the time period. SCLC patients diagnosed during the same time period most commonly received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The share of NSCLC patients receiving IO treatment grew significantly from only 0.9% amongst patients diagnosed in 2014 to 5.6% amongst patients diagnosed in 2017. The share of NSCLC patients receiving surgery only also grew during the same time period from 12.1% to 14.8%. Amongst SCLC patients there is a systematic decline in the share of patients receiving radiotherapy only, which decreases from 21.7% amongst patients diagnosed in 2014 to 7.6% amongst patients diagnosed in 2017

Average costs per patient for the first 24 months after diagnosis are on average lowest for those NSCLC patients with a weaker performance status at diagnosis and higher for those with a better performance status (). On the basis of the study population there are no statistically significant trends in the average costs per patient by the patient’s performance status at the time of diagnosis.

Discussion

The main finding in this study is that treatment costs increase over the observation period, in line with previous findings [Citation10]. Both the average cost of the first 12 months as well as the first 24 months after diagnosis increase over time. The annual increase in the nominal 24-month costs was 10.4% for NSCLC and 7.3% for SCLC patients.

For treatment of NSCLC patients, the cost categories, medicine costs and inpatient care cost showed an increase. For SCLC the largest increase occurred only in the category of inpatient care costs. Our study findings support previous studies [Citation5–9], indicating that the introduction of new treatments, including IO therapies in the treatment of NSCLC could explain the increase in medicine costs.

The increase in costs for NSCLC treatment was found highest for those diagnosed with stage IV cancer. New treatments introduced in the care of NSCLC have targeted metastatic diseases which has resulted in both more patients with advanced stages receiving treatments, as well as patients receiving more expensive treatments than patients in the past [Citation20]. At the same time treatments for stage I and II patients did not change significantly, leading to a much more moderate cost development for these patient groups. The treatment of patients diagnosed with a stage III NSCLC is on average the most expensive. This is most likely due to that stage III NSCLC patients are eligible to receive a variety of treatments and they might require hospitalization as their condition weakens.

The overall NSCLC treatment cost increase is somewhat curbed by the much more moderate cost increase in stage I and stage II NSCLC. However, the majority of patients are diagnosed in stage III and IV so the medicine costs for NSCLC can be expected to continue increasing at least for some years, as the uptake of IO treatments increases.

As for the treatment of SCLC, the category of inpatient costs has driven the costs while medicine costs have remained stable. It is likely that this will change once new treatments, e.g., IO therapies become available also for SCLC.

The strength of the study is that it covers a large population making the results robust. However, the coverage of stage and performance status information for 2014 and 2015 is low and we could not completely rule out that changes in patient characteristics might also impact on the cost increase. Another limitation of the study is that to enable comparability for the whole patient cohort we were only able to consider the costs for the first 24 months. In addition, the statistical significance of trends in costs was tested by linear models. A linear model may not fit for complex data patterns. It is suitable for monotonic and steadily changing costs. However, we have only four data points (years 2014–2017) and a simple model reduced the risk of overfitting. In further study, it is planned to collect more data and also study models of non-linear growth.

In order to contain increases in the total treatment costs of lung cancer, improving the early diagnostics of lung cancer would be important especially if assuming that not all lung cancers detected at an early stage eventually metastasize. The possibilities of screening and targeted screening in the future might help in detecting lung cancer earlier. Early detection would also help improve the treatment outcomes in terms of survival, which have not improved in Finland as much as in other Nordic countries [Citation21] in the recent years.

In the latest years there has been new indications which are not reflected yet in this study cohort but which could impact on the costs. Once the new treatment becomes available for patients who earlier had no treatment options further research should consider the effects of the new treatments: what is the increase in overall survival – and importantly, what is the quality-adjusted increase in the overall survival.

Conclusions

For patients diagnosed in 2014, the average cost of treatment of the first 24 months was €19000 and for those diagnosed in 2015 €22,000. The average total treatment cost for these patients incurred up until the end of 2019 was €26,300 and €27,200, respectively, compared to previous research indicating €29,100 per patient for year 2014 over the whole lung cancer treatment period in Finland [Citation3]. The explanations for the cost increase are increased medicine costs (for NSCLC), and the increased percentage of patients being actively treated.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (84.2 KB)Disclosure statement

R-LL, SK, IH, MN, EP and FH report that their employer has received funding from MSD, SK, A-MA and KN were employees of MSD at the time of the study. ST, MS, JA, AK and JK report having received consultancy fees from MSD.

Data availability statement for trends in cost of treatment of lung cancer patients in 2014–2019 in Finland

The Data in this study is generated at four University hospitals in Finland. Raw data were generated at Helsinki University Hospital (HYKS), Tampere University Hospital (TAYS), Kuopio University Hospital (KYS) and Turku University Hospital (TYKS). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the University hospitals by study permit and data request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, et al. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: a population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(12):1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70442-X

- Laudicella M, Walsh B, Burns E, et al. Cost of care for cancer patients in England: evidence from population-based patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1286–1292. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.77

- Torkki P, Leskelä RL, Linna M, et al. Cancer costs and outcomes in the Finnish population 2004–2014. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(2):297–303. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1343495

- Yabroff KR, Mariotto AB, Feuer E, et al. Projections of the costs associated with colorectal cancer care in the United States, 2000–2020. Health Econ. 2008;17(8):947–959. doi: 10.1002/hec.1307

- Bhalla N, Brooker R, Brada M. Combining immunotherapy and radiotherapy in lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 13):S1447–S1460. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.107

- Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):299–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8

- Leidl R, Wacker M, Schwarzkopf L. Better understanding of the health care costs of lung cancer and the implications. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10(4):373–375. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1149064

- Koivunen J, Knuuttila A, Mali P. Levinneen keuhkosyövän nykyaikainen lääkehoito – mitä totunnaisten solunsalpaajien lisäksi? Duodecim. 2016;132:555–560.

- Palmer S, Kuhlmann GL, Pothier K. IO nation: the rise of immuno-oncology, current pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine (formerly current pharmacogenomics). CPPM. 2015;12(3):176–181. doi: 10.2174/1875692113666150115222451

- DiBonaventura MD, Shah-Manek B, Higginbottom K, et al. Adherence to recommended clinical guidelines in extensive disease small-cell lung cancer across the US, Europe, and Japan. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:355–366. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S183216

- Lindqvist J, Jekunen A, Sihvo E, et al. Effect of adherence to treatment guidelines on overall survival in elderly non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2022;171:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.07.006

- Nicolson M. ES05. 01 lung cancer survival: progress and challenges. Thor Oncol. 2019;14(10):S24. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.087

- Voda A, Bostan I. Public health care financing and the costs of cancer care: a cross-national analysis. Cancers. 2018;10(4):117. doi: 10.3390/cancers10040117

- Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(10):933–980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3

- McGuire A, Martin M, Lenz C, et al. Treatment cost of non-small cell lung cancer in three european countries: comparisons across France, Germany, and England using administrative databases. J Med Econ. 2015;18(7):525–532. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1032974

- Fox KM, Brooks J, Kim J. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: costs associated with disease progression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(9):565–571.

- Skinner KE, Fernandes AW, Walker MS, et al. Healthcare costs in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and disease progression during targeted therapy: a real-world observational study. J Med Econ. 2018;21(2):192–200. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1389744

- Kapiainen S, Väisänen A, Haula T. Terveyden- ja sosiaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset suomessa vuonna 2011. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. 2014.

- Hoitojaksotietokanta [Data file], Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2020.

- Leskelä R-L, Peltonen E, Haavisto I, et al. Trends in treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in Finland 2014–2019. Acta Oncol. 2022;61(5):641–648. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2022.2042474

- Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3