Introduction

This case series describes three unusual cases of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas (SNSCC). Moreover, the associated literature has been systematically reviewed. As HPV, especially high-risk types 16 and 18, has been considered a possible culprit in the development of SNSCC, studies have addressed the significance of HPV infection in SNSCC in particular [Citation1–4]. A systematic review reported approximately 30% of SNSCCs being HPV positive – this both with and without association to inverted papilloma [Citation5].

Symptoms of sinonasal malignancy are often quite unspecific, which often leads to diagnostic delay even with a classic presentation; in cases with unusual symptoms, clinical diagnosis may be rather challenging—as illustrated by the presented cases.

Materials and methods

In April 2022, two authors (BBL and SS) systematically searched PubMed and Embase for articles in English using the following keywords: sinonasal carcinoma and sinonasal cancer combined with human papillomavirus, HPV, ‘Papillomaviridae’, and p16. See Supplementary for the detailed search strategy. We defined the research question according to the PICO (Patient, Interventions, Comparison, and Outcome) structure; all patients were diagnosed with SNSCC and were tested for HPV status. Regarding comparison, we compared the prognosis of HPV positive SNSCCs with HPV negative SNSCCs, and outcome was survival.

The study population for the case series consisted of three patients with HPV-positive SNSCC treated at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, and Audiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark from 2010 to 2020. The SCC diagnosis was confirmed by morphology and immunohistochemical analysis; HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma (HMSC) cases were excluded.

HPV analysis was performed as part of the standard diagnostic workup testing for HPV DNA using HPV DNA PCR with general primers GP5+/6+ (GP5+: 50-TTTGTTACTGTGGTAGATACTAC-3′0; GP6+: 50-GAAAAATAAACTGTAAATCATATTC-3′0) and Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Naerum, Denmark) followed by inspection of PCR products by gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, genotyping was performed using next generation sequencing (NuGEN Technologies Inc., San Francisco, California) for sequencing on Illumina instruments as previously described [Citation6] or by using the HPV chip assay (VisionArray® HPV Chip by Zytovision, Germany).

Results

Systematic review

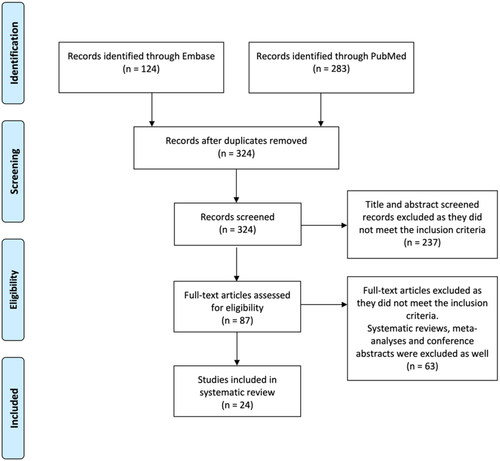

The Embase and PubMed search generated a total of 324 articles after removal of duplicates. Twenty-four articles met the inclusion criteria, as shown in . The studies reported data on more than 4000 SNSCC patients. Study characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Study characteristics: inclusion period, source, and number of cases.

HVP and overall survival

Eighteen of the included studies (n = 3688) reported on the occurrence of HPV in SNSCC and the association with OS [Citation1,Citation4,Citation7–13,Citation15,Citation18–23,Citation25,Citation26]. Eleven of these studies (n = 3396) reported improved survival in HPV-positive patients [Citation1,Citation7,Citation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation20–23], whereas seven studies (n = 292) did not find any statistically difference in survival rate [Citation4,Citation9–11,Citation19,Citation25,Citation26]. Two of the studies (n = 108) reported a trend towards better overall survival for the HPV positive SNSCCs, but did not find the correlation being statistically significant [Citation4,Citation11].

HPV and p16

Eleven of the studies examined the role of p16 as a surrogate marker for HPV [Citation4,Citation8,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17,Citation20,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28]. Six studies (n = 475) reported that p16 positivity was strongly associated with the presence of HPV DNA [Citation8,Citation10,Citation13,Citation17,Citation20,Citation28]. Svajdler et al. moreover, detected that sensitivity of transcriptionally-active HPV status, via p16 as a surrogate marker, was 62.5% and specificity was 92.3% [Citation10]. In several small cohorts (n = 139), p16 was not found to be a reliable surrogate marker of HPV status in SNSCC [Citation14,Citation16,Citation24,Citation27].

Case study

Three patients with HPV-positive SNSCC were included in this study as they had an unusual presentation and course of disease. The patients were seen and treated in accordance with the Danish fast track cancer program and consented to participate in this research report [Citation29].

Case 1 – cancer of unknown primary

A 57-year-old woman presented with an HPV16-positive head and neck cancer of unknown primary (CUP). The initial treatment of her CUP was left-sided-superficial parotidectomy revealing an intraparotid lymph node with non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (NKSCC) and no additional parotid pathology. Moreover, the surgical intervention comprised dissection of lymph nodes in levels II and III on the left side and bilateral tonsillectomy. Afterwards, resection of the lingual tonsils was performed using transoral robotic surgery (TORS). The primary tumour was not identified despite fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), computed tomography (CT) scan, and additional multiple biopsies from oro- and rhinopharynx.

Four years after the CUP diagnosis, the patient presented with nasal stenosis and ulceration on the left side of the nasal septum. Due to her history, an FDG-PET/CT was performed, and based on the findings a biopsy was obtained from the nasal ulceration. The latter demonstrated HPV-positive SNSCC, T1N0M0, containing the same HPV-type as her previous head and neck CUP. In agreement with our pathologists, the primary tumour was finally identified i.e. four years following her initial cancer diagnosis. Subsequently, a lateral alar rhinotomy, with resection of most of the nasal septum, was performed followed by local postoperative radiation therapy (RT).

The cancer recurred 15 months following the nasal surgery, suspected due to odontalgia, epistaxis and ulceration of the nose. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and biopsies showed SCC involvement of the left side of the maxillary bone close to the nasal septum. Surgery was performed in October 2020 with radical resection of the palate and the maxillary bone from region +6 to 6+.

Six months later, FDG-PET/CT and biopsies showed recurrence of the cancer at T-site. The patient was treated with chemo- and immunotherapy. 18 months following the FDG-PET/CT, a new recurrence in the oral cavity (upper gum region +1 to +3) was identified. The patient is now in palliative treatment with chemo- and immunotherapy.

Case 2 – multiple recurrences

A 63-year-old man was referred with a history of recurring painless left-sided epistaxis in 2009. Initial biopsy from the anterior part of the left side of the nasal septum contained a papillomatous tumour with carcinoma in situ. Subsequent biopsies demonstrated an HPV16- and p16-positive SNSCC, T1N0M0. Clinically, tumour invasion to the right side was visible and the patient was treated with radiotherapy (RT). A few months after RT, a rhinectomy was performed due to recurrence involving most of the nasal septum and the overlying skin.

During the following five years post RT, the patient had six minor recurrences in different sinonasal locations. These were all HPV-positive and treated surgically. At follow-up, seven months after the sixth recurrence, new biopsies containing SNSCC were obtained from the left lamina papyracea area close to a previously identified recurrence of the SCC. The tumour was surgically removed.

New recurrences close to the previous location were removed six months following the aforementioned surgery. New biopsies obtained at follow-up three months later, from areas close to the latter, showed HPV16-positive SCC. As it seemed that following the biopsies there was no visible tumour left, the patient declined further extensive surgery. At the subsequent examination one month later, no tumour or ulcer was visible.

In 2019, i.e. five years after the latest recurrence, the patient complained of irritation and bleeding from the nasal cavity. Biopsies confirmed a recurrence again at the lamina papyracea. Subsequent endoscopic surgery was performed, obtaining radicality. Currently, there is no sign of recurrence.

Case 3 – HPV39

In a 51-year-old woman with enlarged cervical lymph nodes and a lymph node fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) containing SCC, an FDG-PET/CT scan demonstrated a focus in rhinopharynx with bilateral neck metastases. Biopsies from rhinopharynx and a resected cervical lymph node contained the same type of tumour, which were HPV39-positive. Treatment with three series of chemotherapy, followed by RT on T-site and weekly chemotherapy, was commenced.

Five years following this, a new primary tumour—an HPV39- and p16-positive SNSCC on the left side of the nasal septum reaching the ipsilateral ethmoidal cells—was diagnosed. Surgical resection of the tumour, as well as reconstruction of the external nose followed by post-operative RT, was performed.

Nineteen months later, recurrence was suspected due to an FDG-PET/CT showing PET-positive foci in the chin, left submental lymph node, and posterior left nasal cavity. Excision of the PET-positive tumour, lymph nodes, and initial T-site was performed, demonstrating HPV39-positive recurrence. Six months following the surgery, new biopsies of the right facial lymph node, level I, showed another recurrence, which was resected successfully. Currently, five years after, there is no sign of recurrence.

Discussion

The current three cases illustrate a wide range of symptoms and disease course associated with HPV-positive SNSCC. As SNSCC is not a frequent disease, and because of the vague and unspecific symptoms associated with it, the clinical diagnosis can be difficult—even more so with uncommon symptoms [Citation30]. This was clearly illustrated by the case of the patient previously treated for an HPV-positive CUP of the neck before the final diagnosis of the HPV-positive SNSCC. To the best of our knowledge, only one other case of SNSCC presenting as CUP has been described [Citation31]. Lymph node metastases are not common at presentation of SNSCC; only around 10% present with nodal neck metastases, and in follow up, around 10% develop distant metastases (often alongside local recurrence) mostly those with higher tumour stages and tumour located in the maxillary sinus [Citation30,Citation32]. Interestingly, the primary lesion, in all our three cases, was found in the nasal cavity. This demonstrates that HPV infection in the nasal cavity might be more frequent than previously expected [Citation33].

All three included patients were diagnosed with multiple recurrence of their SNSCC. This demonstrates the importance of long-term systematic follow-up in patients with HPV-positive SNSCC, and how focus also should include other locations comprising neighbouring organs like nasopharynx. However, the result of an active and persistent therapy seems to have been justified.

The association between HPV and OPSCC, and the improved prognosis of the HPV-positive OPSCC patients compared with HPV-negative OPSCC, is well-established. Currently, the significance of HPV in SNSCC is still unclear, but the association is investigated [Citation34–38]. Our review highlights that several studies indicate that HPV may play a role in the development of sinonasal cancer—particularly SNSCC [Citation5,Citation18,Citation39–41]. In parallel with OPSCC, a positive prognostic value of HPV-positivity in SNSCC has been described. This was also reported as significant in eleven of our included studies [Citation1,Citation7,Citation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation20–23]. Four of the enrolled studies reported on data from the National Cancer Database. As the data was extracted with overlapping time period, it is seen as a limitation to our review [Citation1,Citation18,Citation22,Citation25]. Whether the improved prognosis can be attributed in part to younger patients in the HPV-positive SNSCC patient group, remains to be explored [Citation4,Citation8].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the cases described in this letter serve as reminders of the multifaceted symptoms of HPV-positive SNSCC, which should also be taken into consideration when usual workup fails to identify the primary tumour in a patient with CUP. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the importance of an awareness of HPV in SNSCC and systematic long-term follow-up along attention on new locations for recurrency. The general significance of HPV-positivity in SNSCC has not yet been determined - nor has the role of p16 overexpression in SNSCC, but our review indicates that patients with HPV-positive SNSCC may have a better survival than patients with HPV-negative SNSCC. Testing for HPV and p16 in the SNSCC is also recommended for future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

References

- Kılıç S, Kılıç SS, Kim ES, et al. Significance of human papillomavirus positivity in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(10):980–989. doi: 10.1002/alr.21996.

- But-Hadzic J, Jenko K, Poljak M, et al. Sinonasal inverted papilloma associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Radiol Oncol. 2011;45(4):267–272. doi: 10.2478/v10019-011-0033-4.

- Bishop JA, Ma X-J, Wang H, et al. Detection of transcriptionally active high-risk HPV in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as visualized by a novel E6/E7 mRNA in situ hybridization method. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(12):1874–1882. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318265fb2b.

- Tendron A, Classe M, Casiraghi O, et al. Prognostic analysis of HPV status in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(8):1874. doi: 10.3390/cancers14081874.

- Sjöstedt S, von Buchwald C, Agander TK, et al. Impact of human papillomavirus in sinonasal cancer—a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(9):1175–1191. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2021.195092.

- Garset-Zamani M, Carlander AF, Jakobsen KK, et al. Impact of specific high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes on survival in oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2022;150(7):1174–1183. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33893.

- Nishikawa D, Sasaki E, Suzuki H, et al. Treatment outcome and pattern of recurrence of sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma with EGFR-mutation and human papillomavirus. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2021;49(6):494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2021.02.016.

- Cabal VN, Menéndez M, Vivanco B, et al. EGFR mutation and HPV infection in sinonasal inverted papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma. Rhin. 2020;58(4):368–376. doi: 10.4193/Rhin19.371.

- Cohen E, Coviello C, Menaker S, et al. P16 and human papillomavirus in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2020;42(8):2021–2029. doi: 10.1002/hed.26134.

- Doescher J, Piontek G, Wirth M, et al. Epstein–Barr virus infection is strictly associated with the metastatic spread of sinonasal squamous-cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(10):929–934. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.008.

- Larque AB, Hakim S, Ordi J, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus is transcriptionally active in a subset of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(3):343–351. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.155.

- Hongo T, Yamamoto H, Jiromaru R, et al. PD-L1 expression, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, mismatch repair deficiency, EGFR alteration and HPV infection in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(11):1966–1978. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00868-w.

- Li H, Torabi SJ, Yarbrough WG, et al. Association of human papillomavirus status at head and neck carcinoma subsites with overall survival. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(6):519–525. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0395.

- Hu C, Quan H, Yan L, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma with and without association of inverted papilloma in Eastern China. Infect Agent Cancer. 2020;15:36. doi: 10.1186/s13027-020-00298-4.

- Laco J, Sieglová K, Vošmiková H, et al. The presence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 mRNA transcripts in a subset of sinonasal carcinomas is evidence of involvement of HPV in its etiopathogenesis. Virchows Arch. 2015;467(4):405–415. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1812-x.

- Jo VY, Mills SE, Stoler MH, et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: frequent association with human papillomavirus infection and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(11):1720–1724. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b6d8e6.

- Kim Y, Joo YH, Kim MS, et al. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus and its genotype distribution in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54(5):411–418. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2020.06.22.

- Jiromaru R. HPV-related sinonasal carcinoma clinicopathologic features, diagnostic utility of p16 and rb immunohistochemistry, and EGFR copy number alteration. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(3):305–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001410.

- Oliver JR, Lieberman SM, Tam MM, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1413–1423. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32679.

- Schlussel Markovic E, Marqueen KE, Sindhu KK, et al. The prognostic significance of human papilloma virus in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1070–1078. doi: 10.1002/lio2.468.

- Hongo T, Yamamoto H, Jiromaru R, et al. Clinicopathologic significance of EGFR. Mutation and 2021;45(1):108–118. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001566.

- Svajdler M. Significance of transcriptionally-active high-risk human papillomavirus in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma: case series and a meta-analysis. Neoplasma. 2020;67(6):1456–1463. doi: 10.4149/neo_2020_200330N332.

- Al-Qurayshi Z, Smith R, Walsh JE. Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma presentation and outcome: a national perspective. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2020;129(11):1049–1055. doi: 10.1177/0003489420929048.

- Yamashita Y, Hasegawa M, Deng Z, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and immunohistochemical expression of cell cycle proteins pRb, p53, and p16INK4a in sinonasal diseases. Infect Agents Cancer. 2015;10(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13027-015-0019-8.

- Alos L, Moyano S, Nadal A, et al. Human papillomaviruses are identified in a subgroup of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas with favorable outcome. Cancer. 2009;115(12):2701–2709. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24309.

- Chowdhury N, Alvi S, Kimura K, et al. Outcomes of HPV-related nasal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(7):1600–1603. doi: 10.1002/lary.26477.

- Cheung FMF, Lau TWS, Cheung LKN, et al. Schneiderian papillomas and carcinomas: a retrospective study with special reference to p53 and p16 tumor suppressor gene expression and association with HPV. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2010;89(10):E5–E12. doi: 10.1177/014556131008901002.

- Bishop JA, Guo TW, Smith DF, et al. Human papillomavirus-related carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(2):185–192. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182698673.

- Toustrup K, Lambertsen K, Birke-Sørensen H, et al. Reduction in waiting time for diagnosis and treatment of head and neck cancer – a fast track study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(5):636–641. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.551139.

- Lewis JS. Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma: a review with emphasis on emerging histologic subtypes and the role of human papillomavirus. Head and Neck Pathol. 2016;10(1):60–67. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0692-y.

- Zhang SC, Wei L, Zhou SH, et al. Inability of PET/CT to identify a primary sinonasal inverted papilloma with squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with a submandibular lymph node metastasis: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):749–753. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3328.

- Ahn PH, Mitra N, Alonso-Basanta M, et al. Risk of lymph node metastasis and recommendations for elective nodal treatment in squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus: a SEER analysis. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(9-10):1107–1114. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1216656.

- Forslund O, Johansson H, Madsen KG, et al. The nasal mucosa contains a large spectrum of human papillomavirus types from the betapapillomavirus and gammapapillomavirus genera. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(8):1335–1341. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit326.

- Zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers – a brief historical account. Virology. 2009;384(2):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046.

- Chow LQM. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):60–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1715715.

- Grønhøj C, Jensen D, Dehlendorff C, et al. Impact of time to treatment initiation in patients with human papillomavirus-positive and -negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Oncol. 2018;30(6):375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2018.02.025.

- Carlander ALF, Grønhøj Larsen C, Jensen DH, et al. Continuing rise in oropharyngeal cancer in a high HPV prevalence area: a Danish population-based study from 2011 to 2014. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.015.

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217.

- Syrjänen S, Syrjänen K. HPV in head and neck carcinomas: different HPV profiles in oropharyngeal carcinomas – why? Acta Cytol. 2019;63(2):124–142. doi: 10.1159/000495727.

- Grønhøj Larsen C, Jensen DH, Fenger Carlander A-L, et al. Novel nomograms for survival and progression in HPV + and HPV- oropharyngeal cancer: a population-based study of 1,542 consecutive patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(44):71761–71772. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12335.

- Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S. Detection of human papillomavirus in sinonasal carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(6):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.08.017.