Abstract

Background

Benign struma ovarii (SO) with synchronous ascites and elevated CA125 level is extremely rare that the incidence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors remain unclear.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of patients with SO treated in our hospital between 1980 and 2022. Logistic regression was used to identify potential risk factors for SO patients presenting with ascites and elevated CA125 levels. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the predictive performance of the identified risk factors.

Results

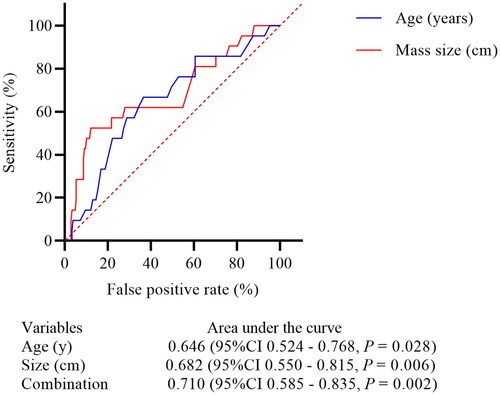

A total of 21 patients with synchronous ascites and elevated CA125 levels were identified in 229 patients with SO, the crude incidence rate was 9.17%, and four patients (1.75%) had pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome. Ascites were completely involuted within 1 month postoperatively and the serum CA125 level decreased to normal between 3 d and 6 weeks after surgery. Multivariate logistic regression showed that age ≥49 years (OR 3.71, 95% CI 1.29 − 10.64, p = 0.015), tumor size ≥10.0 cm (OR 8.79, 95% CI 3.05 − 25.35, p < 0.001), and proliferative SO (OR 11.16, 95% CI 3.01 − 41.47, p < 0.001) were the independent risk factors for patients presenting ascites and elevated CA 125 level. The ROC curve revealed that the predictive performance for age and tumor size was unsatisfactory with an area under the curve (AUC) was 0.646 and 0.682, respectively. Linear regression demonstrated that the serum CA125 level has a moderate positive correlation with the volume of ascites (log2CA125 = 0.6272*log2ascites + 2.099, p = 0.0001, R2 = 0.5576).

Conclusions

Less than one-tenth of patients with SO would present ascites and elevated CA125 levels, while age ≥49 years, tumor sizes ≥10 cm, and the presence of proliferative SO were the risk factors.

Introduction

Struma ovarii (SO) is an uncommon, benign, monodermal ovarian teratoma that thyroid tissue comprising more than 50% of all its components, which accounts for less than 5% of ovarian teratomas [Citation1,Citation2]. Patients with SO usually present with unspecific symptoms, but may manifest ascites, hydrothorax, and/or elevated CA-125 levels, which clinically mimic ovarian carcinoma [Citation3–6]. Accurate preoperative identification of SO patients presenting with ascites and elevated CA125 levels will be helpful to reduce the chance of overtreatment. It has been reported that approximately 20% of the patients with SO present with ascites and elevated CA125 levels [Citation3,Citation6]. Nevertheless, this cluster of symptoms remains extremely rare only about 20 cases have been documented in the English literature [Citation3,Citation4]. However, all these cases were reported as part of case reports or within cohorts with very small sample sizes. No study has investigated the incidence of ascites and elevated CA125 levels in SO patients, or the risk factors for this comorbid presentation. Furthermore, some authors have suggested that elevated CA125 levels may be secondary to ascites, but no study has fully examined this association [Citation7]. Therefore, more detailed information about these signs and symptoms in patients with SO is needed.

To evaluate the incidence, clinical characteristics, and pathological features, and risk factors for SO patients presenting with ascites and elevated CA125 levels, we conducted a single-center retrospective study. Evaluation of identified clinical predictors and a description of patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA125 levels were subsequently performed. The relationship between ascites and serum CA125 levels in SO patients was further assessed.

Material and methods

The Peking Union Medical College Hospital Ethics Committee approved this study. Patients with pathologically confirmed benign SO who were treated at Peking Union Medical College Hospital between 1980 and 2022 were included. Comprehensive medical information, including patients’ demographic characteristics, and clinical and pathological features, was collected. We screened all patients with the ICD-10 code for benign SO (ICD-10 code: D27 M9090/0) in their medical records, and excluded those with incomplete medical record data (the inclusion process was summarized in Figure S1). We divided patients into two groups: patients with synchronous ascites and elevated CA125 levels (Group A), and patients did not present both ascites and elevated CA125 levels (Group B). Exploratory factors include age at diagnosis (<49 or ≥49 years), tumor components (i.e., tumors that were pure SO vs. tumors with other teratoma components), proliferative SO (yes or no; we defined proliferative SO as tumors that contained a proliferative SO component), tumor size (<10.0 or ≥10.0 cm), coexistence with other non-teratoma tumors (yes or no), SO location (left or right), and ascites (yes or no). The cutoff value of age and tumor size was based on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Predictive models based on clinical characteristics without pathologic features were also established. We also included a brief description of the patients who presented with hydrothorax and ascites (i.e., pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome, defined as non-fibroma benign ovarian tumors such as teratoma, fibromyomas, cystadenomas that had coexisted ascites and hydrothorax [Citation8]) along with elevated CA125 levels.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as means ± standard deviations if they were normally distributed or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) if they were not normally distributed. Discrete variables were expressed as counts (percentages). Between-group variables were compared using univariate analysis. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U-test, depending on the distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Variables in the univariate analysis with p values <0.1 were selected for potential inclusion in the multivariate logistic regression model. Forward, stepwise logistic regressions were performed to determine the potential risk factors for SO with synchronous ascites and elevated CA125 levels. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values were calculated. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the predictive performance of the identified risk factors. We used linear regression to assess the relationship between ascites volume and serum CA125 levels in patients who presented with those symptoms. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) or GraphPad Prism Version 8.0 (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

A total of 12,864 patients with ovarian teratoma were identified. Of 229 of these patients with SO (1.78%) and were included in the screening process. There were also 33 patients with ovarian strumal carcinoid and 13 patients with malignant struma ovarii (MSO) in the teratoma cohort. The median age at diagnosis was 43.0 years (range: 17–92) and patients with SO usually had ovarian massin moderate size. Elevated CA125 and CA19-9 levels were observed in 20.5 and 8.7% patients, respectively.

We identified a total of 39 patients presented with ascites (range: 80–12000 ml), 21 of whom also had elevated CA125 levels. Ovarian cystectomy, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (USO), and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (H/BSO) were the most common surgical interventions for these tumors (). However, due to coexisting malignancies within the female genital tract or intraoperative ovarian cancer diagnosis, nine patients also underwent surgical staging surgeries.

Table 1. The clinical characteristics of so patients and those with ascites and elevated CA125 levels (N = 21).

Clinical characteristics of patients with synchronous ascites and elevated CA125 levels

Twenty-one patients had SO with ascites and elevated CA125 levels, with a crude incidence rate of approximately 9.17%. Most of them presented with abdominal masses or nonspecific discomfort, such as abdominal pain without distinct clinical manifestations. Five patients presented with abdominal distension caused by massive ascites, and one presented with chest distress caused by hydrothorax. However, no one presented with hyperthyroidism. Unlike other teratomas that can mostly be diagnosed prior to surgery, two-thirds of these patients had suspected ovarian malignancies. We summarize each patients’ clinical features in .

H/BSO (8 cases) was the most common surgical treatment, followed by USO (5 cases). There were three patients who underwent ovarian cystectomy and three who underwent BSO. Intraoperative frozen pathology was administered in 12 patients, eight of whom had SO and two of whom had teratomas. Another two had suspected ovarian carcinomas, which led to comprehensive surgical staging including H/BSO, omentectomy, appendectomy, and lymphadenectomy (). Postoperative paraffin revealed that 17 patients had pure SO and four had teratoma with SO. Moreover, SO with adenomatous proliferation was found in four patients, while another two patients had proliferative follicles. Furthermore, five patients had contralateral tumors, four of which were benign teratomas and one of which was a juvenile granulosa cell tumor. Cytological pathology was performed in all patients using ascites fluid or peritoneal washings, but no tumor cells were found.

The ascites rapidly vanished within one month postoperatively in all patients, and the serum CA125 levels fell to normal between three days and six weeks postoperatively. During a median follow-up time period of 5.8 years, no patients had disease relapse, but one died of a cardiovascular accident.

Risk factors, predictive model, and model performance

Clinical and pathological features were compared between the two groups (A vs. B, ). Those who presented with ascites and elevated CA125 levels were significantly older (50.2 vs. 43.5 years, p = 0.047) and had larger mass sizes (9.5 vs. 7.2 cm, p = 0.027), compared with those who did not. Similar results were found in the proportion of patients aged over 49 years and who had mass sizes larger than 10 cm. However, the mean volume of ascites, location of ovarian tumor, and coexistence with other non-teratoma ovarian tumors did not statistically differ between the two groups. Pathological results revealed that patients in group A had a significantly higher rate of proliferative components in SO (p < 0.001).

Table 2. Logistics regression to identify potential risk factors for patients with ascites and elevated CA125 levels (N = 229).

Patient age, tumor size, pure SO, and presence of proliferative SO were included in multivariate logistic regression model, while age ≥49 years (OR 3.71, 95% CI 1.29−10.64, p = 0.015), tumor size ≥10.0 cm (OR 8.79, 95% CI 3.05−25.35, p < 0.001), and proliferative SO (OR 11.16, 95% CI 3.01−41.47, p < 0.001) were factors which predicted a significantly higher probability of SO patients that may present with ascites and elevated CA 125 levels (). Age ≥49 years (OR 3.66, 95% CI 1.35−9.93, p = 0.011) and tumor size ≥10.0 cm (OR 7.08, 95% CI 2.68−18.76, p < 0.001) remained statistically significant after we excluded pathological features (Table S1). Similar results were also observed when we defined age and tumor size as continuous variables (Table S2).

ROC curves demonstrated that an age of 49.0 years (sensitivity 66.67% and specificity 63.46%) and mass size of 10.0 cm (sensitivity 52.38% and specificity 87.98%) was the best cutoff points for predicting patients presenting with ascites and elevated CA125 levels. However, the independent predictive performance of these two factors was unsatisfactory, and a combination of these two factors only showed mild improvement. The AUC for age, mass size, and combination of age and mass size were 0.646 (95% CI 0.524−0.768, p = 0.028), 0.682 (95% CI 0.550−0.815, p = 0.006), and 0.710 (95% CI 0.585−0.835, p = 0.002), respectively (). The main findings and clinical significance are shown in Figure S2.

Linear regression of ascites volume and serum CA125 level

Data from patients who presented with ascites and elevated CA125 levels (group A) were further used to identify the potential relationships between the volume of ascites (mL) and serum CA125 levels (U/mL). Linear regressions showed that serum CA125 levels (Y, dependent variable) were positively associated with the volume of ascites (X, independent variable). The estimated equation was log2CA125 = 0.6272*log2ascites + 2.099 but this correlation was moderate (p = 0.0001, R2 = 0.5576, Figure S3), indicating that the serum CA125 levels may depend on complex factors.

Patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated CA125 levels

Four patients presented with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome with elevated CA125 levels, which only accounted for 1.75% of SO patients. These characteristics are summarized in .

Table 3. The summary of four patients with pseudo-Meigs’s syndrome and elevated CA125 levels.

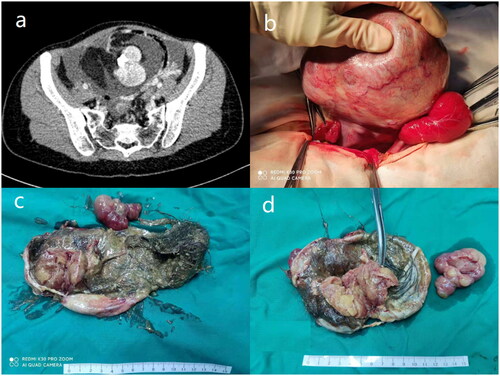

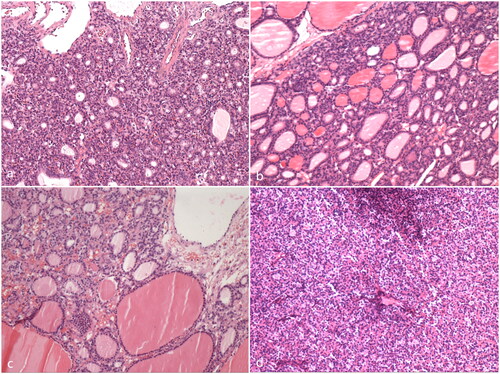

Thoracentesis and/or abdominocentesis and drainage were conducted in two patients to relieve symptoms, but both samples were cytologically negative. These four patients all underwent surgical exploration, and clear, faint yellow ascites along with left ovarian solid-cystic tumors were observed intraoperatively (e.g., , Case 4). USO was first conducted in these four patients, and the intraoperative frozen pathology indicated SO in three patients and mature teratoma in one patient. BSO and H/BSO were further administered in two and one patient, respectively. Paraffin pathology confirmed the diagnosis of SO in these patients (), two of whom had SO with follicle adenomatous hyperplasia. No adjuvant therapy was applied, and the patients recovered uneventfully.

Figure 2. Intraoperative view of one patient with synchronous pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA125 level (Case 4). (a) CT scan identified an 11.5*7.5*13.1 cm solid-cystic pelvic mass and massive ascites. (b) The mass was of left ovary origin with a smooth surface and plenty of blood vessels. (c) The cutting surface of the ovarian tumor revealed a cystic-solid structure with lipids and hair. (d) The cutting surface of the solid portion was in dark red, yellowish color.

Figure 3. The pathology of the four patients with synchronous pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA125 level (HE staining, 100X). (a) Case 1; (b) Case 2; (c) Case 3; (d) Case 4.

Both the ascites and hydrothorax rapidly subsided and completely disappeared within one month in all patients after surgeries, and serum CA125 levels decreased to normal no more than six weeks postoperatively. The diagnosis of pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome was finally established in all patients, and there was no evidence of disease after a median follow-up time of 36 months.

Discussion

Our study presents the largest cohort of benign SO patients presenting with ascites and elevated serum CA125 levels. We found that less than one-tenth of SO patients presented with these symptoms, whereas age ≥49 years, tumor size ≥10.0 cm, and proliferative SO were risk factors in this population. Serum CA125 level had a moderate positive correlation with ascites volume. Furthermore, a briefly description of SO patients who presented with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA125 levels was also presented.

This was the first study to investigate the incidence of SO patients who presented both with ascites and elevated CA125 levels. Previous studies reported about 20 cases of SO patients with ascites and elevated CA125 levels and proposed that ascites occurred in 15–20% of patients and pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome was speculated to exist in about 5% of cases [Citation3,Citation4,Citation9–11]. Our study revealed a comparable incidence rate of ascites (17%) but a much lower pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome incidence rate (<2%). Nevertheless, the incidence of SO patients with ascites and elevated CA125 was over 9%, which was a much higher rate than had been determined in previous work. These results indicate that SO deserves more diagnostic consideration when patients present with ascites and elevated CA125 levels resembling ovarian malignancy, because surgical overtreatment may be administered in case of incorrect preoperative diagnosis.

Previously, there were no known risk factors for predicting whether SO patients would present with ascites and elevated CA125 levels. Elevated CA125 was mostly observed in ovarian or endometrial cancer, endometriosis, and inflammation [Citation12]. However, in benign tumors, tumor size, transudative mechanisms in the tumor surface, obstruction of peritoneal lymphatics by tumors, and increased permeability secondary to inflammation were hypothesized to be factors that would influence the formation of ascites, while elevated CA125 levels were believed to be secondary to ascites [Citation5,Citation7,Citation9]. However, these hypotheses mostly originated from case reports without deeper validation. Additionally, prior biochemical analysis of ascites suggested that it was transudative in nature. We identified that age ≥49 years, tumor size ≥10.0 cm, and proliferative SO significantly increased the probability of ascites and elevated CA125 levels amongst SO patients. Furthermore, proliferative SO was the most important risk factor that increased the probability of ascites formation and elevated CA125 levels by more than tenfold. A possible mechanism underlying this correlation is that as-yet-unknown substances secreted by proliferative SO accelerate the formation of ascites. Patient age and tumor size remain significant risk factors regardless of the presence of proliferative SO, suggesting that these two factors also independently impact the formation of ascites. Nevertheless, the sensitivity and specificity of age and tumor size were unsatisfactory in predicting ascites and elevated CA125 incidence, either alone or in combination. This finding suggests that pathologic factors mainly contribute to the formation of ascites, while advanced patient age and tumor size have a synergistic effect on this process. Proteomic analysis [Citation13] of patients with SO presenting with different clinical and pathological features may be a practical method for further validation.

Although the preoperative diagnosis of SO remains challenging, SO does have some relatively specific imaging features [Citation6,Citation14,Citation15]. Savelli et al. proposed that typical SO (pure SO) may present as a multilobulate solid-cystic mass with moderate vascularization on ultrasonography and that SO diagnosis may be suspected when ‘struma pearls’ (i.e., smooth roundish solid areas) are identified [Citation6]. Ikeuchi et al. found that high-density cysts might be characteristic features of SO on CT [Citation16]. Another study found that high attenuation areas and calcifications in the solid component of struma on CT were common features of SO [Citation17]. Dujardin et al. summarized MRI findings in SO patients and concluded that unilateral multilobulate surfaces and thick septa composed of multiple cysts of variable signal intensity or moderately enhancing solid components with ‘lace-like appearances’ were commonly seen in SO [Citation14]. Furthermore, precise preoperative diagnosis of SO with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated CA125 levels based on a combination of 131I scintigraphy and 18F-FDG PET have also been reported [Citation3].

To reduce the chances of surgical overtreatment in patients with SO, it may be practical to use a combination of preoperative imaging and intraoperative frozen pathology to improve diagnostic accuracy. For patients with suspected SO or ovarian malignancy but with some SO-related imaging features, the risk factors identified in our study may be helpful for the purposes of initial screening. Intraoperative frozen pathology could be used to determine the surgical option, as our study revealed that more than 80% of patients who had intraoperative frozen pathology were correctly diagnosed with either SO or benign teratomas. Furthermore, conservative surgical approaches can still be used even if strumal carcinoid or could not be excluded by intraoperative frozen pathology. In accordance with our results, prior research has shown that strumal carcinoid and MSO are the two most common malignant transformations arising in SO [Citation1]. Our previous series of studies demonstrated excellent survival outcomes in strumal carcinoid and MSO, regardless of the surgical options [Citation18–20]. Moreover, conservative surgery or fertility-sparing surgery was also acceptable even for those with metastatic MSO [Citation20].

The relationship between ascites and serum CA125 levels in patients with SO is not yet fully understood. Some researchers suspected that elevated CA125 levels in SO were secondary to ascites rather than to the tumors themselves, but there was no parallel relationship between the serum CA125 levels and the amount of ascites [Citation4,Citation7]. The mechanical irritation and inflammatory responses from the tumor and ascites may increase the expression of CA125 in adjacent mesothelial cells [Citation9,Citation11,Citation21]. These hypotheses were supported by Buttin et al. and Lin et al. who used IHC staining for CA125 and found positive results in the omentum or on peritoneal surfaces, but negative in tumors in patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome from other benign ovarian benign tumors [Citation22,Citation23]. Our results are the first to demonstrate a quantitative relationship between serum CA125 levels and ascites volumes using linear regression. In our cohort, serum CA125 levels had a moderate positive correlation with the volume of ascites. However, we also note that several patients had both massive ascites volumes (∼4 L) and normal serum CA125 level in our cohort, illustrating the complex relationships underlying these two factors.

The retrospective nature and relatively small sample size are two major limitations of our study. Additionally, the unsatisfactory predictive performance of our model suggests that precise preoperative diagnosis still challenging. Further study is warranted.

Conclusion

Less than one-tenth of SO patients would present with ascites and elevated CA125 levels that which mimic ovarian cancer, while age ≥49 years, tumor sizes ≥10 cm, and the presence of proliferative SO were risk factors for the development of ascites and elevated serum CA125. However, the predictive performances of both single and combined identified clinical factor models were unsatisfactory. Serum CA125 levels had a moderate positive correlation with the volume of ascites in patients with SO.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (reference number: S-K1198) and all methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the four patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and others were waived by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the four patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Author contributions

Sijian Li wrote the manuscript and conducted statistical analysis; Ruping Hong participated in manuscript writing and finished the pathological analysis; Min Yin, Xinyue Zhang, and Tianyu Zhang completed the work of follow-up and participated in statistical analysis; Jiaxin Yang conceived the study design and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the Supplementary Information Files. The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wei S, Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA. Pathology of struma ovarii: a report of 96 cases. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26(4):342–348. doi:10.1007/s12022-015-9396-1.

- Roth LM, Talerman A. The enigma of struma ovarii. Pathology. 2007;39(1):139–146. doi:10.1080/00313020601123979.

- Fujiwara S, Tsuyoshi H, Nishimura T, et al. Precise preoperative diagnosis of struma ovarii with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome mimicking ovarian cancer with the combination of (131)I scintigraphy and (18)F-FDG PET: case report and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13048-018-0383-2.

- Wang S, He X, Yang H, et al. Struma ovarii associated with ascites and elevated CA125: two case reports and review of the literature. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1291–1296. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S379128.

- Mostaghel N, Enzevaei A, Zare K, et al. Struma ovarii associated with Pseudo-Meig’s syndrome and high serum level of CA 125; a case report. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5:10. doi:10.1186/1757-2215-5-10.

- Savelli L, Testa AC, Timmerman D, et al. Imaging of gynecological disease (4): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of struma ovarii. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(2):210–219. doi:10.1002/uog.5396.

- Loizzi V, Cormio G, Resta L, et al. Pseudo-Meigs syndrome and elevated CA125 associated with struma ovarii. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(1):282–284. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.040.

- Kazanov L, Ander DS, Enriquez E, et al. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):404–405. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90141-3.

- Mui MP, Tam KF, Tam FK, et al. Coexistence of struma ovarii with marked ascites and elevated CA-125 levels: case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(5):753–757. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0794-1.

- Jiang W, Lu X, Zhu ZL, et al. Struma ovarii associated with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA 125: a case report and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res. 2010;3:18. doi:10.1186/1757-2215-3-18.

- Jin C, Dong R, Bu H, et al. Coexistence of benign struma ovarii, pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome and elevated serum CA 125: case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(4):1739–1742. doi:10.3892/ol.2015.2927.

- Ginath S, Menczer J, Fintsi Y, et al. Tissue and serum CA125 expression in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(4):372–375. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01007.x.

- Zhang Z, Wu S, Stenoien DL, et al. High-throughput proteomics. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif). 2014;7:427–454. doi:10.1146/annurev-anchem-071213-020216.

- Dujardin MI, Sekhri P, Turnbull LW. Struma ovarii: role of imaging? Insights Imaging. 2014;5(1):41–51. doi:10.1007/s13244-013-0303-3.

- Sahin H, Abdullazade S, Sanci M. Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a cutting edge overview on imaging features. Insights Imaging. 2017;8(2):227–241. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0539-9.

- Ikeuchi T, Koyama T, Tamai K, et al. CT and MR features of struma ovarii. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(5):904–910. doi:10.1007/s00261-011-9817-7.

- Shen J, Xia X, Lin Y, et al. Diagnosis of struma ovarii with medical imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36(5):627–631. doi:10.1007/s00261-010-9664-y.

- Li S, Yang T, Xiang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of malignant struma ovarii confined to the ovary. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):383. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08118-7.

- Li S, Wang X, Sui X, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival outcomes in patients with ovarian strumal carcinoid. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1090. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-10167-5.

- Li S, Yang T, Li X, et al. FIGO stage IV and age over 55 years as prognostic predicators in patients with metastatic malignant struma ovarii. Front Oncol. 2020;10:584917. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.584917.

- Mitrou S, Manek S, Kehoe S. Cystic struma ovarii presenting as pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome with elevated CA125 levels. A case report and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(2):372–375. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00998.x.

- Lin JY, Angel C, Sickel JZ. Meigs syndrome with elevated serum CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(3 Pt 2):563–566.

- Buttin BM, Cohn DE, Herzog TJ. Meigs’ syndrome with an elevated CA 125 from benign Brenner tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 Pt 2):980–982. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01562-9.