Abstract

Background

The interest in patient involvement is increasing in health research, however, is not yet well described in adolescents and young adults (AYA) with palliative cancer, such as AYAs with an uncertain and/or poor cancer prognosis (UPCP). This study aimed to document the process of involving AYAs with a UPCP as partners in research including their experiences, the impact, and our lessons learned.

Materials and Methods

AYAs with a UPCP were recruited via healthcare professionals and patients to involve as research partners in the qualitative interview study. To define their role and tasks in each research phase we used the participation matrix.

Results

In total six AYAs with a UPCP were involved as research partners and five as co-thinkers. They were involved in initiating topics, developing study design, interviewing, analyzing data, and dissemination of information. Together with the researcher, they co-produced the information letters and interview guides and implemented aftercare and extra support. The research partners ensured that the data was relevant, correctly interpreted and that results were translated to peers and clinical practice. AYAs themselves felt useful, found people who understand their challenges, and were able to create a legacy.

Conclusion

The benefits of involving AYAs with a UPCP as research partners cannot be stressed enough, both for the study as well as for the AYAs themselves, but there are challenges. Researchers should anticipate and address those challenges during the planning phase of the study. This article provides practical tips on how to do so.

Background

The importance of patient involvement in research, which is defined as research being carried out with or by patients rather than to, about, or for them, is growing and more promoted by funding agencies, institutions, and academic journals in healthcare sciences [Citation1,Citation2]. Patient involvement in research can be beneficial in terms of formulation of more relevant research questions, more patient-tailored recruitment strategies, and higher impact of research findings for care practices [Citation3–6]. Intrinsic benefits of patient involvement include patients feeling more empowered and valued, contributing to more participatory healthcare and patient-centeredness [Citation4,Citation6–8]. Despite the demonstrated benefits described in the literature, in practice, patient involvement is currently often a box-ticking exercise and tokenistic, indicating that patients still do not have much influence [Citation3].

Concerning the benefits, patient involvement might be extra useful in an underserved and understudied young population with serious conditions, such as adolescents and young adults with cancer (AYA). AYA patients are those diagnosed with cancer for the first time between the ages of 15–39 years [Citation9,Citation10]. AYAs form a unique and vulnerable patient population because of their age, developmental life phase and not yet fully understood tumor biology [Citation11]. Within this AYA cancer population, several patient involvement initiatives emerged in the past couple of years [Citation12,Citation13]. For example, the ‘AYA Dreamteams’ was created in the Netherlands, in which clinical experts and AYAs work together successfully to discuss ways to improve care and conduct studies [Citation14].

Patient involvement is typically rare in a non-curative setting, particularly among young patients like AYAs with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis (UPCP). These AYAs are diagnosed with advanced or metastatic cancer and will prematurely die from cancer since there is no reasonable hope of cure, but have no immediate threat of death [Citation15]. The life expectancy of AYAs with a UPCP significantly improved due to new treatment options like personalized targeted therapy and immunotherapies [Citation15,Citation16]. It could be that this patient group is seen as more challenging to involve in research given their unpredictable and fluctuating disease pattern [Citation17–19]. On top of that, there is a tendency to view young patients as vulnerable and inexperienced [Citation6,Citation20]. Nevertheless, previous research showed that it is feasible and valuable to involve patients with limited survival chances or in the end-of-life phase but that researchers are not aware of the benefits or possibilities [Citation1,Citation17,Citation19].

To enhance meaningful patient involvement, Smits et al. developed the Involvement Matrix in which they distinguished three research phases for which patients can fulfill different participation roles ranging from low to high impact [Citation21]. The Involvement Matrix can start a dialogue between the patient and researcher to examine which role the patient prefers within the research project and prevent tokenism [Citation21]. To study the patient involvement experiences of young cancer patients, van Ham et al. merged the Involvement Matrix of Smits with all research phases of the research cycle and adjusted a new role (practical support) and two new research phases (grant application, recruitment) [Citation17,Citation21].

Well-described studies on how patients can be partners in research are scarce and available advice for researchers focuses mainly on general involvement principles [Citation4,Citation5,Citation22–24]. A previous study found that in practice collaboration with patients in all research phases within a single project is unusual [Citation17]. It is important to involve AYAs with a UPCP in research to ensure that the rapid development of personalized care will be aligned with the needs and priorities of this patient group. Therefore, we included AYAs with a UPCP as research partners in all research phases of the INVAYA interview study. In this article, we aimed to (1) document the process of involving AYAs with a UPCP as partner in the INVAYA study and (2) provide insight into the impact of their involvement. We want to share the lessons learned and provide practical tips for researchers and patients.

Material and methods

Context of the research: INVAYA study

The INVAYA study is part of a large multicenter research infrastructure called COMPRAYA [Citation25]. Within the INVAYA study, qualitative interviews are conducted to get a better understanding of the daily life challenges, coping, and healthcare needs of AYAs with a UPCP. First, healthcare professionals (HCPs) providing care to AYAs with a UPCP were interviewed about the challenges and coping of the AYAs, and which challenges the HCPs face when providing care to them [Citation26]. Second, AYAs were interviewed about their daily life challenges, coping, and healthcare experiences and received a follow-up call after one-to two weeks to allow them to add some extra information and to check in emotionally [Citation18,Citation27]. At last, the informal caregivers were interviewed about the challenges and coping of the AYAs, and their own experiences. The INVAYA study, including the patient involvement activities obtained ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of The Netherlands Cancer Institute (IRBd20-205).

Research partners

Research partners in the INVAYA study were AYAs with a UPCP. Inclusion criteria for being a research partner were: (1) diagnosed with any type of advanced cancer for the first time between 18 and 39 years of age. This is the age definition of AYA cancer patients within the Netherlands since they have specialized pediatric oncology services (0–18) [Citation28]. Criteria were furthermore, (2) no reasonable hope of a cure, indicating that the patient would die prematurely due to cancer, and (3) the ability to speak and understand Dutch [Citation15].

In this article, the role of a research partner is defined as being actively involved in at least one of the phases of research. Patients and researchers have an equal amount of influence and they jointly take decisions [Citation17,Citation21,Citation29]. Some AYAs with a UPCP choose to be a co-thinker, which is someone who is asked to give their opinion or advice [Citation21].

Procedure

Participants were recruited via HCPs, researchers, patient organizations, research partners and via the researcher (VB) after participation of the INVAYA interview study. After the research partner agreed, the researcher (VB), with a psychology background, provided further information about the INVAYA study, the research phases, and the possible roles and tasks within the study. The wishes for participation, roles, and tasks were discussed with the research partners with the help of the participation matrix as adapted by van Ham et al. [Citation17]. AYAs were able to choose to be involved at a different intensity and within another role per research phase and task to ensure flexibility [Citation19].

Online meetings were organized to connect the AYAs, and to provide more in-depth information about the study objectives, method, and timeline. The AYA research partners preferred to stay in contact by mail and/or WhatsApp and we decided to use Google Drive to share all study documents. We made agreements on the best moments to meet and AYAs preferred to put deadlines on tasks. Everybody was always allowed to provide feedback and nothing was mandatory, however, it was their own responsibility to indicate if something did not work out. To protect the AYAs’ mental wellbeing, we agreed that everyone could leave meetings without explanation if the conversation was too emotional or confrontational. Before the start of each research phase, a new meeting was planned to inform the research partners about the status quo, results, and next steps. Dependent on the research phase and tasks, more meetings were scheduled. To objectively measure the impact of this patient involvement initiative, the researcher kept a logbook with all the contact moments and every change in the documents was recorded.

We followed the GRIPP2 form (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public) as a guideline for reporting our study results (Supplement 1)[Citation5].

Results

Demographics

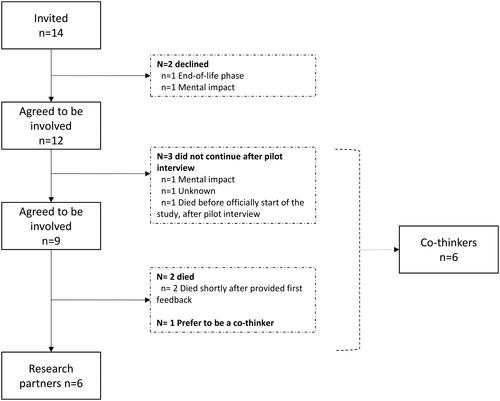

We invited 14 AYAs with a UPCP to be a research partners or actively involved in another role within the INVAYA study. Eventually, this resulted in six research partners and six co-thinkers with a mean age of 30.4 involved from October 2019 until February 2023 ( and ).

Table 1. Demographics of 12 AYAs who were actively involved as research partner or in another role.

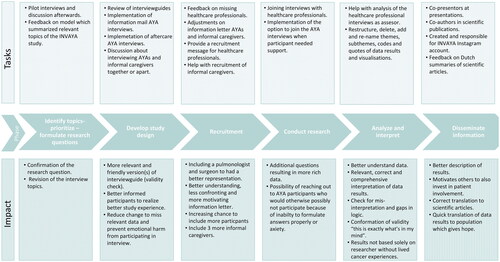

Involvement per research phase: tasks and impact

In this section we describe the involvement tasks of the research partners for each research phase including the process and impact of their collaboration. See for an overview of the roles of the research partners per research phase within the INVAYA study and for a summary of the tasks performed by the research partners and co-thinkers, and their impact.

Table 2. Involvement matrix adjusted for the INVAYA study including number of research partners per research phase and role in the study [Citation17].

Identify topics, prioritize and formulate research questions (4 meetings)

First, we organized a brainstorm session for the INVAYA study including researchers, HCPs, and an AYA with a UPCP to further identify and prioritize topics and formulate more specific research questions. We conducted five pilot interviews to test interview topics and questions. Afterward, we had a discussion with the AYA co-thinkers on the relevant missing interview topics. Additionally, they all gave feedback on a model in which we summarized all the relevant topics regarding AYAs with a UPCP, their informal caregivers and HCPs. The pilot interviews and feedback on the model resulted in a confirmation of the research question and revision of the interview topics.

Develop study design (6 meetings)

For the interviews of the HCPs, the research partners were asked to review the interview guide. Discussions between research partners and the researchers based on results from the reviewed interview guide resulted in a new version with some additional questions based on what they wanted to know.

After the pilot interviews and discussion as described previously, the researcher (VB) revised the interview topics and created an interview guide for the AYA interviews. The research partners reviewed this interview guide. They helped with prioritizing topics, provided feedback on missing topics, the number of questions and duration of the interview, and formulation the questions with a specific emphasis on the degree of emotional confrontation. The input of the research partners resulted in six feedback rounds to complete the final version of the interview guide. The most important changes were; wording, removal of irrelevant questions, and additional questions about missed support and the relationship with their HCP. One research partner who participated in the pilot study admitted that she had answered the questions more optimistically and experienced the questions as emotionally intense. The research partners advocated for better aftercare to overcome the emotional impact, and give the study participants the chance to add some new information. After discussions with the research partners and the research team (WG, OH), we implemented a follow-up call a one-to-two weeks after the interview to check for additional information and emotional impact. If more support was needed, we could connect with the AYA nurse specialist involved in the study. To reduce the emotional impact of the interview, the research partners were advised to send the interview questions or more information beforehand to participants. After discussion with the research partners and research team, we decided to send an extensive description of the interview topics and information about the possible emotional impact. We received positive feedback on the explanation in the e-mail and participants seemed to appreciate the follow-up call. Remarkably, nobody asked for additional support.

The research partners reviewed the interview guide for the informal caregivers and helped to find an informal caregiver to participate in a pilot interview. Furthermore, in collaboration with the research team, we discussed the options to interview the AYA and their informal caregiver together or to interview informal caregivers separately. Research partners shared that they do not openly discuss everything with their loved ones and assume that their loved ones do not share everything with the AYA, which made us decide to interview the informal caregivers on their own.

Recruitment (2 meetings)

For the recruitment of the HCPs, AYAs recommended including a surgeon and a pulmonary physician since we did not include them in the first place. We included these HCPS to have a good representation of the HCPs that treat AYAs with a UPCP.

Research partners were mainly involved in the recruitment process of the AYAs and their informal caregivers. In a team meeting, we discussed the best way to formulate the definition of AYAs with a UPCP in the information letter. This was essential because we did not want to be too confrontational or scare people off but wanted the right people to recognize themselves in the description. Additionally, two AYAs provided feedback with track changes by mail, which was discussed in an online team meeting at a later time. Besides the changes to describe the study in a more understandable way, the AYAs preferred to describe the purpose of the study as early as possible in the information letter since this was very important and relevant for them to decide whether to participate in a study. Furthermore, one of the AYAs had been included as a contact person in the patient information letter, in case patients had questions and preferred to ask these questions to a research partner who may be better able to empathize with the existing concerns or wishes. However, no one had used this option. At last, the research partners formulated a short message helping HCPs to invite AYAs for the INVAYA study.

For the recruitment of informal caregivers, AYAs also helped with the phrasing of the information letter. Since we had difficulties with the recruitment of informal caregivers, the AYAs recruited informal caregivers via their own network resulting in three additional participants.

Conducting research (4 meetings)

The interviews with HCPs, AYAs, and informal caregivers were conducted by the researcher and trained colleagues. The research partners were not interested in conducting the interviews due to possible confrontation, lack of skills, and time. However, two research partners were willing to attend three (out of 49) interviews with HCPs in order to ask additional in-depth questions fueled by their own patient experience. The HCP was able to check answers with the AYA research partner, which enriched the data.

The research partners were convinced that they could offer support and help during the AYA interviews by creating a safe space where AYA participants feel comfortable, helping them to formulate answers or ask follow-up questions that the researcher might not (dare to) ask. After discussion with the research partners and the research team, we provided this option to the participants. We made clear rules about the role of the research partners within the interview, the debriefing, setting own boundaries and the willingness to stay in contact with the participant. However, in practice, no participant chose the extra support of a research partner.

Analyze and interpret (12 meetings)

One AYA helped us with the analysis of the HCP interview data as third assessor when the first and second coder had questions about the coding. In total, we had two short meetings to solve some questions.

For the analysis of the AYA interviews, we had around 10 meetings with the research partners discussing results. The researcher presented themes, subthemes, and codes supported by quotes for the daily life challenges, coping, and healthcare experiences as reported by AYAs with a UPCP. The research partners were asked to think about the structure of themes, their names, and if they can relate to these findings to check for misinterpretation. After in-depth discussions, this resulted in restructuring, deletion, addition and re-naming themes, subthemes, codes, quotes, and modification of the visualization of the results. The data of the informal caregiver interviews has not been analyzed as of yet.

Disseminate information

Four research partners co-presented with the researcher(VB) about the results, talked about their own cancer experiences, shared their experiences as research partners, and answered questions. Dissemination of the study results to clinical practice and to the AYA population was a priority for the research partners since knowing that there were people out there doing research on the psychosocial impact of your disease gives hope. Two AYAs suggested sharing our research trajectory on Instagram. We discussed the content, division of tasks and designed a logo. Together with the researcher, these two AYAs were responsible for the Instagram account. The Instagram account and the logo created unity and connection.

Thirdly, the research partners were coauthors of the scientific articles. Since not everyone was able to read the English scientific articles, we discussed the articles in the group meetings. This also brought the idea to write Dutch summaries of the articles, which were published on websites creating content for Dutch AYA cancer patients, and were sent to all the study participants.

Discussion

This article illustrates that it is possible to involve AYAs with a UPCP in every study phase and gives examples of how this can be done in qualitative research. The research partners modified the study protocol, co-produced the information letters and interview guides, and implemented aftercare and extra support for the participants. They ensured that data was relevant, correctly interpreted and no themes were missing, and contributed to making the study results more accessible to peers. They had the possibility to be actively involved as an equal partner but sometimes chose to be a co-thinker or advisor. We translated our lessons learned into practical tips to guide future patient involvement initiatives. This guide is added to the supplementary materials (Supplement 2).

The most important contribution of the research partners was that our research was based on needs as conveyed by AYAs with a UPCP. The research partners were pivotal in guiding us to refine the information letters and mails, which facilitated recruitment and may have contributed to a good response rate. Help from the research partners with the interview guides resulted in sensitive, less distressing and relevant questions. The research partners used their lived experience to interpret the data, which was essential for us to help us understand the findings from a patient perspective, especially since AYAs with a UPCP are a unique and understudied group. Since research partners believed that it was essential to share our study developments and results regularly with different stakeholders, we invested in disseminating information to enhance our reach among their peers. The patient-researcher collaboration made it possible to take the experiences and needs of AYA cancer patients within the research process into account, resulting in an increased participation rate, satisfaction of the participants, research ethics, validity and relevance of the research process and findings. Our experiences in involving patients as partners in this study supports the findings of other researchers that patient involvement contributes to more relevant research questions, suitable study design and better interpretation and translation of the results [Citation3–6,Citation22,Citation30].

In line with previous research, AYAs also benefited from their role as research partners [Citation4,Citation6,Citation19]. First, being actively involved as a research partner made them feel useful. Especially, since part of them were struggling with feeling inferior to their previous self or others because of their cancer and negative consequences in work life [Citation18]. Research partners gained new information, skills (e.g., public speaking), new opportunities, and insights about themselves, built a network, and became more self-confident. In this way, AYAs played an active role in the creation of their own healthcare environment and their individual health to improve their quality of life. Together, they strengthened this form of empowerment since they helped each other to reframe and reinterpret their challenges to create new perspectives, which in turn led to better adjustment to their UPCP [Citation8]. In line with other patient involvement initiatives, patient involvement enables research partners to do something valuable for AYA peers [Citation6,Citation7]. Altogether, this indicates that no hope of cure and the possibility of premature death are no reasons not to invite AYAs with a UPCP to be a research partner. It even seems important to include them in research since being a research partner can be their legacy, reduces feelings of loneliness, and empowers them to participate in society again.

Despite efforts in planning, structuring, and discussing the ‘who, what and how’ of patient involvement, we still experienced several challenges. First, there was no financial compensation available for this patient involvement initiative, so we could not offer the research partners a financial reward for their work. This caused an imbalance in the patient-researcher relationship in the beginning since the researcher did not dare to ask too much time. However, it seemed that the research partners were intrinsically motivated and that a lack of financial compensation was no problem. Additionally, a lack of budget and limited time also resulted in being unable to provide training to the research partners in terms of scientific terms, qualitative research, and scientific publications, which could help them to contribute in a more optimal way. It seems that patient involvement is not yet commonly used in all phases of research and current academic cultures and funders do not yet always support or give enough space for patient involvement [Citation17,Citation31]. For example, there are little to no patients on Institutional Review Boards, indicating that research is still performed for patients instead of with them. This resulted in ethical challenges regarding decisions about AYAs conducting the interviews and follow-up calls. Tension of ethical challenges, lack of finances, no training, and project time restrictions resulted in not always being able to meet the preferences of the research partners. For future research, we would advocate to get detailed insight into the burden and cost of patient involvement and the possible limitations for meaningful engagement.

This involvement initiative has limitations. Firstly, this study did not succeed to recruit a diverse group of research partners, since most of them are relatively highly educated, Caucasian, and woman. Mostly assertive AYAs who were open to sharing their cancer experiences were included and it could be that we missed the perspective of seldom-heard patients. Furthermore, an expected challenge of working with AYAs with a UPCP was the uncertain and unpredictable disease pattern. This resulted in different compositions of our group meetings due to cancelations by physical, medical, and mental issues and absence for a longer period. This required a flexible approach and an enlarged pool of research partners to reduce the expectations for the individual AYAs and to ensure that the researcher was not dependent on one AYA. Additionally, due to the uncertain and unpredictable disease pattern, there was a possibility that one of the research partners could die during the study, which would be extremely confrontational for the research partners. We implemented debriefing and follow-up calls after one of the research partners died or when emotional topics were discussed during team meetings. However, since one of the research partners died unexpectedly it was more complicated for the researcher to anticipate quickly to her own emotions and the reactions of the research partners. It seems important to make agreements and guidelines regarding leaving and dying and check these repeatedly. The research partners appreciated that they were able to share their medical and personal updates with their peers during team meetings. Despite the fact that this offered them mutual support and enriched data about their experiences, this did cost an unforeseen amount of extra time. At last, it turned out to be difficult to give the researcher and research partners an equal amount of influence in this research project because of ethical challenges, lack of finances and training. In this patient involvement initiative, the researcher ultimately was in charge and the research partners had as much influence as possible. Since many studies did not provide a definition of research partner, future research should be more open about the definition and reflection of how it turns out in practice [Citation32]. These current and future lessons learned may contribute to a more appropriate definition of a research partner.

Conclusion

This article demonstrates a successful example of how patient involvement with AYAs with a UPCP can be embedded in qualitative research. The rewards of involving AYAs with a UPCP as research partners cannot be emphasized enough, but there are challenges. Researchers should anticipate and address those challenges already during the planning phase of the study. This study shows that AYAs with a UPCP are not only open to participate as research partner but also gain positive benefits from their involvement. Future research in this particular patient population can be more meaningful when this important observation is taken into consideration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors thank CT, EU, FD, FG, FL, IP, ND for their active contribution as research partner or co-thinker in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this study as no new data were created or analyzed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pii KH, Schou LH, Piil K, et al. Current trends in patient and public involvement in cancer research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2019;22(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/hex.12841.

- INVOLVE. What is public involvement in research? cited 2020. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/posttypefaq/what-is-public-involvement-in-research/.

- Schölvinck A-FM, Schuitmaker TJ, Broerse JEJS. Embedding meaningful patient involvement in the process of proposal appraisal at the Dutch cancer society. Sci Public Policy. 2019;46(2):254–263. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy055.

- Høeg BL, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Skaarup JA, et al. Whose perspective is it anyway? Dilemmas of patient involvement in the development of a randomized clinical trial - a qualitative study. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):634–641. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1566776.

- Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453.

- van Schelven F, Boeije H, Rademakers J. Evaluating meaningful impact of patient and public involvement: a Q methodology study among researchers and young people with a chronic condition. Health Expect. 2022;25(2):712–720. doi: 10.1111/hex.13418.

- van Schelven F, Boeije H, Inhulsen M-B, et al. “We know what we are talking about”: experiences of young people with a chronic condition involved in a participatory youth panel and their perceived impact. Child Care in Practice. 2021;27(2):191–207. doi: 10.1080/13575279.2019.1680529.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026.

- Department of Health and Human Services NIo, National Cancer Institute, LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance. Closing the gap; research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer: a report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group 2996 [cited 2023 February 8]. Available from: https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/ayao_prg_report_2006_final.pdf.

- Ferrari A, Barr RD. International evolution in AYA oncology: current status and future expectations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(9) doi: 10.1002/pbc.26528.

- Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Closing the Gap: research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer 2006 [cited 2023 January 4]. Available from: https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/ayao_prg_report_2006_final.pdf.

- Sleeman SHE, Reuvers MJP, Manten-Horst E, et al. Let me know if there’s anything I can do for you’, the development of a mobile application for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer and their loved ones to reconnect after diagnosis. Cancers . 2022;14(5)doi: 10.3390/cancers14051178.

- Elsbernd A, Hjerming M, Visler C, et al. Using cocreation in the process of designing a smartphone app for adolescents and young adults With cancer: prototype development study. JMIR Form Res. 2018;2(2):e23. doi: 10.2196/formative.9842.

- Vandekerckhove P, de Mul M, de Groot L, et al. Lessons for employing participatory design when developing care for young people with cancer: a qualitative multiple-case study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2021;10(4):404–417. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2020.0098.

- Burgers VWG, van der Graaf WTA, van der Meer DJ, et al. Adolescents and young adults living with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis: the "new" lost tribe. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(3):240–246. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7696.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836.

- van Ham CR, Burgers VWG, Sleeman SHE, et al. A qualitative study on the involvement of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer during multiple research phases: "plan, structure, and discuss. Res Involv Engagem. 2022;8(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40900-022-00362-w.

- Burgers VWG, van den Bent MJ, Dirven L, et al. Finding my way in a maze while the clock is ticking": the daily life challenges of adolescents and young adults with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:994934. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.994934.

- Ludwig C, Graham ID, Gifford W, et al. Partnering with frail or seriously ill patients in research: a systematic review. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:52. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00225-2.

- Brady L-M, Presto J. How do we know what works? Evaluating data on the extent and impact of young people’s involvement in English health research. RFA. 2020;4(2):194–206. doi: 10.14324/RFA.04.2.05.

- Smits DW, van Meeteren K, Klem M, et al. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: the involvement matrix. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00188-4.

- van Schelven F, Boeije H, Mariën V, et al. Patient and public involvement of young people with a chronic condition in projects in health and social care: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2020;23(4):789–801. doi: 10.1111/hex.13069.

- De Wit M, Kvien T, Gossec L. Patient participation as an integral part of patient-reported outcomes development ensures the representation of the patient voice: a case study from the field of rheumatology. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e000129. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000129.

- Staniszewska S, Denegri S. Patient and public involvement in research: future challenges. Evid Based Nurs. 2013;16(3):69. doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101406.

- Husson O, Ligtenberg MJL, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Comprehensive assessment of incidence, risk factors, and mechanisms of impaired medical and psychosocial health outcomes among adolescents and young adults with cancer: protocol of the prospective observational COMPRAYA cohort study. Cancers. 2021;13(10):2348. doi: 10.3390/cancers13102348.

- Burgers VWG, van den Bent MJ, Darlington AE, et al. A qualitative study on the challenges health care professionals face when caring for adolescents and young adults with an uncertain and/or poor cancer prognosis. ESMO Open. 2022;7(3):100476. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100476.

- Burgers VWG, van den Bent MJ, Rietjens JAC, et al. “Double awareness”—adolescents and young adults coping with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis: a qualitative study [original research]. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1026090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1026090.

- Kaal S. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer: towards optimising age-specific care. Esch: Proefschrift-aio.nl; 2018.

- Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation. JAIP. 1969;35(4):216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Chiu CG, Mitchell TL, Fitch MI. From patient to participant: enhancing the validity and ethics of cancer research through participatory research. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):237–246. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0464-2.

- O’Mara-Eves A, Laidlaw L, Vigurs C, et al. The value of co-production research project: a rapid critical review of the evidence: co-production collective. 2022; [cited 2023 February 2]. Available from: https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5ffee76a01a63b6b7213780c/63595629676ab598f0e6bf44_ValueCoPro_RapidReviewFull31Oct22.pdf

- McCarron TL, Clement F, Rasiah J, et al. Patients as partners in health research: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1378–1390. doi: 10.1111/hex.13272.