Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor, occurring in adolescents and young adults mainly [Citation1]. Fitfteen to 20% of patients is diagnosed with metastatic disease [Citation2]. Over 80% of them present lung metastases but uncommon sites of metastatic dissemination have been found. Through improvements in multimodal therapy consisting of polychemotherapy regimens and surgery, the 5-year survival rate of localized osteosarcoma patients reaches approximately 70% [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4] and remains stable for three decades. The outcome for patients with metastatic osteosarcoma is very poor, with an average 5-year survival rate of around 40% [Citation2–4] and a median survival time between 10–17 months. Patients experiencing disease relapse have a survival rate rising 20% to 40%. Those whose disease recurred within 2 years of diagnosis have a worse prognosis than those whose disease recurred after 2 years [Citation1,Citation5,Citation6]. The prognosis of subsequent recurrences may be worse. There is no consensus as to the strategy to use in case of multiple relapses but total surgery of all involved sites remains the main prognostic factor for overall survival [Citation2,Citation7–10].

Here, we report the case of a patient with a metastatic to lung osteosarcoma who developed four metastatic but unclassical subsequent recurrences of the disease and who remains alive since the treatment of the last relapse after more than 10 years.

Case report

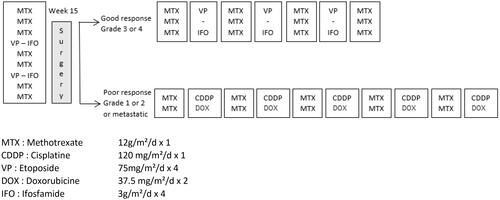

The patient was a 17-year-old male who presented chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the proximal metaphysis-epiphysis of the right tibia with lung metastases dissemination. He was treated according to the OS 94 French protocol [Citation11], as shown in . He received 7 courses of methotrexate (12 g/m2/d) and 2 courses of etoposide (75 mg/m2/d x 4) and ifosfamide (3 g/m2/dx4) as neoadjuvant polychemotherapy regimen. Then, surgical safe resection margins of the primary tumor were performed with total hip endoprosthesis reconstruction. Pathological examination revealed poor histologic necrosis (45% of viable cells) following the preoperative chemotherapy. Furthermore, as there were 2 residual lung nodules after the preoperative chemotherapy, a complete resection of these pulmonary metastases was performed one week after local treatment of the disease. Only one of the 2 nodules was disease viable. Postoperative chemotherapy consisted of 2 courses of methotrexate (12 g/m2) (due to severe intoxication by this drug, the foreseen 8 courses were not performed) and 5 courses of adriamycine (37.5 mg/m2/dx2) and cisplatin (120 mg/m2/dx1).

Figure 1. Systemic therapy according to OS 94 protocol (Citation11).

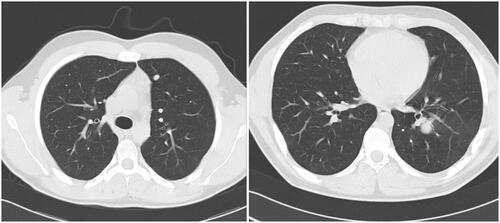

Thirteen months after first-line therapy was completed, the patient experienced a relapse, diagnosed through systematic follow-up. It consisted of 2 centimetric nodules of the left lung, shown in , which were treated by surgery without chemotherapy.

Four months later, a unique nodule of 25 mm in the left lung was diagnosed again, also shown in . The nodule was excised by surgery. Each time, lung lesions were the sole site of metastatic disease and patients achieved complete remission.

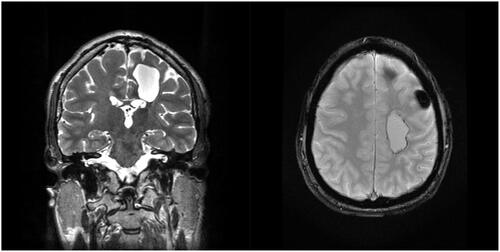

Thirty-three months after the initial diagnosis, the patient was sent to the emergency department with acute symptomatology of intracranial hypertension, facial nerve palsy and right arm paralysis. An MRI was performed and showed a pre rolandic left lesion of 3 cm diameter, shown in . This lesion was removed by stereotaxic neuronavigation. Histological examination revealed recurrent high-grade osteosarcoma. No other metastatic distant site was found, and it was decided to refrain from chemotherapy. The margins of intracranial resection were free of microscopic disease and the patient was in complete remission.

Figure 3. pre Rolandic brain metastasis in IRM, left lesion coronal section T2 (a) and axial section T2* (b).

Last relapse occurred 44 months after the initial diagnosis. The patient was referred to a suburban hospital because of brutal and severe abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen was performed and showed an acute jejunal intussusception. Thus, the patient underwent open surgery during which the surgeon found an intestine wall focal lesion. A complete resection with end-to-end anastomosis was achieved and, once more, histopathology of the focal lesion confirmed high-grade osteosarcoma metastasis. The staging of the disease revealed no other involvement and the patient underwent no further treatment.

He remains alive and disease free with no radiological sign of recurrence (both from plain x-ray, abdominal ultrasound and cerebral MRI) more than 14 years after the initial diagnosis and more than 10 years after his last surgery.

Discussion

Since the 80s, there have been no major changes in osteosarcoma clinical outcomes and/or treatment modalities. Polychemotherapy associated with adequate surgery enables a 5-year overall survival average rate of 70% [Citation1]. It was found that independent prognostic factors which influence outcome include tumor site and size, primary metastases, response to chemotherapy, and surgical remission as well as the fact of relapsing [Citation2,Citation12].

The presence at diagnosis of metastatic disease is the most important prognostic factor with a dramatic drop in 20 to 30% of overall survival rate versus 70 to 80% for non-metastatic patients [Citation1]. It also depends on the location of metastases: patients with pulmonary-only disease fare better than those with bone metastases or other sites of metastases [Citation2]. Complete surgical ablation of the primary and metastatic tumor is a critical prognostic factor and is classically performed after the administration of pre-operative chemotherapy [Citation12,Citation13]. Likewise, the pathology of the tumor after neoadjuvant chemotherapy bodes well for a better outcome if it degree of necrosis is above 90% [Citation1,Citation2].

With an initial metastatic disease and poor-response to the first chemotherapy (only 45% of tumor necrosis), our patient presented a major risk for poor outcome and relapse.

Relapse occurs in approximately 25% of cases and first concerns the lungs, then bones, but other uncommon sites have been noted such as the liver, kidney, pericardium, and stomach [Citation7–9]. The prognosis for patients who relapse remains poor, Spraker et al. reported for the COG a 5-year overall survival of 17.7% after a recurrence [Citation5] and Mialou et al. showed that 80% of metastatic patients experienced either disease progression or disease recurrence and events occurred 0.3–31.0 months after the start of the treatment [Citation2]. More than half of patients with metastatic disease relapse within the first year after diagnosis and the prognosis seems to be worse for those who relapse before the end of the second year [Citation5]. Whereas standard treatment of the first disease consists of a multi-agent chemotherapy regimen in combination with surgery, treatment of the recurrent disease is more controversial. Regarding lung metastases, surgery is the primary treatment and sometimes may be the only one [Citation14–16] and recovery can be reached thanks to repeated surgeries. In the COSS group, Bielack et al. showed that three-quarters of all relapsing patients had surgery and two-thirds received second-line chemotherapy, mostly with multiple agents [Citation7]. However, second-line chemotherapy seemed to bring limited improvements to the outcome. Indeed, the role of chemotherapy to prevent subsequent relapses remains uncertain [Citation10,Citation16–18]. It is now well known that complete resection of all recurrent osteosarcomas is essential for survival and that chemotherapy will have to evolve accordingly [Citation7–10]. In case of an unresectable disease, patients may benefit from radiotherapy, with a limited prolongation of survival without a second complete resection [Citation19]. Furthermore, Bielack et al. reported that subsequent relapses are extremely poor with a median survival time of 1.02 years after the second recurrence, 1.02 years after the third and 0.98 years after the fourth [Citation8]. Lung recurrences tend to be more and more unilateral. Also, the survey demonstrated that some patients became long-term survivors even after multiple recurrences, providing full surgical clearance had taken place. In this case report, the first relapse occurs around 12 months after the first-line therapy was completed. Complete remission was possible because recurrences were pulmonary only and surgically accessible. Control of osteosarcoma of all pulmonary sites was not expected to require extra therapy but two uncommon relapses happened each within twelve months after the surgeries.

Brain recurrence of sarcoma is an uncommon event, but osteosarcoma seems to be the most frequent subtype with an incidence of relapse in the central nervous system of 2 to 6.5%, which rises from 10 to 15% in patients with pulmonary metastases [Citation20–22]. The usual localization is the cerebral cortex and the prognosis is poor with survival of several months at best. The third relapse of the patient was a unique frontal pre-rolandic left lesion and complete resection could be performed by stereotaxic neuronavigation. Similarly, the incidence of intra-abdominal metastasis approaches 2.1% with a median duration from primary diagnosis of 4.5 years, and the outcome is very poor [Citation23]. In this report, disease-free was enabled once more by the surgical accessibility of the intestine wall focal lesion.

The particularity of this case report lies in the long-term survival of a patient presenting very poor prognostic factors at the outset, then several relapses with uncommon localizations but always isolated, all cured by surgery only, enabled by their focal characteristics and accessibility. There are a few similar cases reported in the literature. We noted Tamamyan et al. reported the case of a 6-year-old high-grade osteosarcoma left distal femur who was alive for 11.5 years after complete surgeries of five more common relapses (local, right proximal tibia, pulmonary, soft tissue, and right distal femur) [Citation9].

Conclusion

Second and subsequent relapses of osteosarcoma are associated with very poor outcomes but some reviews show rare cases of long-term survival, depending on the feasibility of surgical clearance. The present report highlights the fact that complete surgical resection of all sites involved by metastases is essential for the control of osteosarcoma recurrences and survival. Furthermore, no systemic therapy was administered as all the relapses were accessible to surgery. Patients with recurrent osteosarcoma should be assessed for surgical treatment which may be recommended at each successive relapse because it seems to be the only way to provide long-term survival. However, for patients with unresectable recurrences, there is a need for novel therapies to improve the patients’ outcome. International cooperation is essential in designing and performing future clinical trials for novel potentially druggable targets or immunotherapies [Citation24–26].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participant of this study gave written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Anderson ME. Update on survival in osteosarcoma. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.022.

- Mialou V, Philip T, Kalifa C, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma at diagnosis: prognostic factors and long-term outcome–the French pediatric experience. Cancer. 2005; 104(5):1100–1109. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21263.

- Piperno-Neumann S, Le Deley MC, Rédini F, et al. Zoledronate in combination with chemotherapy and surgery to treat osteosarcoma (OS2006): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1070–1080. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30096-1.

- Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS, et al. Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed high-grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS-1): an open-label, international, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1396–1408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30214-5.

- Spraker-Perlman HL, Barkauskas DA, Krailo MD, et al. Factors influencing survival after recurrence in osteosarcoma: a report from the children’s oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27444. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27444.

- Thebault E, Piperno-Neumann S, Tran D, et al. Successive osteosarcoma relapses after the first line O2006/sarcome-09 trial: what can we learn for further phase-II trials? Cancers. 2021; 13(7):1683. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071683.

- Kempf-Bielack B, Bielack SS, Jürgens H, et al. Osteosarcoma relapse after combined modality therapy: an analysis of unselected patients in the cooperative osteosarcoma study group (COSS). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):559–568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.063.

- Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Branscheid D, et al. Second and subsequent recurrences of osteosarcoma: presentation, treatment, and outcomes of 249 consecutive cooperative osteosarcoma study group patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(4):557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2305.

- Tamamyan G, Dominkus M, Lang S, et al. Multiple relapses in high-grade osteosarcoma: when to stop aggressive therapy? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(3):529–530. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25360.

- Crompton BD, Goldsby RE, Weinberg VK, et al. Survival after recurrence of osteosarcoma: a 20-year experience at a single institution. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(3):255–259. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20580.

- Le Deley MC, Guinebretière JM, Gentet JC, et al. SFOP OS94: a randomised trial comparing preoperative high-dose methotrexate plus doxorubicin to high-dose methotrexate plus etoposide and ifosfamide in osteosarcoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2007; 43(4):752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.023.

- Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Delling G, et al. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: an analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative steosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(3):776–790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.776.

- Bacci G, Rocca M, Salone M, et al. High grade osteosarcoma of the extremities with lung metastases at presentation: treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and simultaneous resection of primary and metastatic lesions. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(6):415–420. doi: 10.1002/jso.21140.

- Buddingh EP, Anninga JK, Versteegh MIM, et al. Prognostic factors in pulmonary metastasized high-grade osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010; 54(2):216–221. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22293.

- Daw NC, Chou AJ, Jaffe N, et al. Recurrent osteosarcoma with a single pulmonary metastasis: a multi-institutional review. Br J Cancer. 2015; 112(2):278–282. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.585.

- Tirtei E, Asaftei SD, Manicone R, et al. Survival after second and subsequent recurrences in osteosarcoma: a retrospective multicenter analysis. Tumori. 2018;104(3):202–206. doi: 10.1177/0300891617753257.

- Leary SE, Wozniak AW, Billups CA, et al. Survival of pediatric patients after relapsed osteosarcoma: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. Cancer. 2013;119(14):2645–2653. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28111.

- Bacci G, Briccoli A, Longhi A, et al. Treatment and outcome of recurrent osteosarcoma: experience at Rizzoli in 235 patients initially treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(7):748–755. doi: 10.1080/02841860500327503.

- Smolle MA, Szkandera J, Andreou D, et al. Treatment options in unresectable soft tissue and bone sarcoma of the extremities and pelvis – a systematic literature review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(11):799–814. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.200069.

- Salvati M, D'Elia A, Frati A, et al. Sarcoma metastatic to the brain: a series of 35 cases and considerations from 27 years of experience. J Neurooncol. 2010;98(3):373–377. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0085-0.

- Shweikeh F, Bukavina L, Saeed K, et al. Brain metastasis in bone and soft tissue cancers: a review of incidence, interventions and outcomes. Sarcoma. 2014;2014:475175. doi: 10.1155/2014/475175.

- Nieto-Coronel MT, López-Vásquez AD, Marroquín-Flores D, et al. Central nervous system metastasis from osteosarcoma: case report and literature review. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2018; 23(4):266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2018.06.003.

- Rejin K, Aykan OA, Omer G, et al. Intra-abdominal metastasis in osteosarcoma: survey and literature review. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011; 28(7):609–615. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2011.590959.

- Italiano A, Mir O, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced ewing sarcoma or osteosarcoma (CABONE): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020; 21(3):446–455. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30825-3.

- Duffaud F, Mir O, Boudou-Rouquette P, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib in adult patients with metastatic osteosarcoma: a non-comparative, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019; 20(1):120–133. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30742-3.

- Harrison DJ, Geller DS, Gill JD, et al. Current and future therapeutic approaches for osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1413939.