Abstract

Background

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) suffer from substantial symptoms and risk of debilitating complications, yet observational data on their labor market affiliation are scarce.

Material and methods

We conducted a descriptive cohort study using data from Danish nationwide registries, including patients diagnosed with MPN in 2010-2016. Each patient was matched with up to ten comparators without MPN on age, sex, level of education, and region of residence. We assessed pre- and post-diagnosis labor market affiliation, defined as working, unemployed, or receiving sickness benefit, disability pension, retirement pension, or other health-related benefits. Labor market affiliation was assessed weekly from two years pre-diagnosis until death, emigration, or 31 December 2018. For patients and comparators, we reported percentage point (pp) changes in labor market affiliation cross-sectionally from week −104 pre-diagnosis to week 104 post-diagnosis.

Results

The study included 3,342 patients with MPN and 32,737 comparators. From two years pre-diagnosis until two years post-diagnosis, a larger reduction in the proportion working was observed among patients than comparators (essential thrombocythemia: 10.2 [95% CI: 6.3–14.1] vs. 6.8 [95% CI: 5.5–8.0] pp; polycythemia vera: 9.6 [95% CI: 5.9–13.2] vs. 7.4 [95% CI: 6.2–8.7] pp; myelofibrosis: 8.1 [95% CI: 3.0–13.2] vs. 5.8 [95% CI: 4.2–7.5] pp; and unclassifiable MPN: 8.0 [95% CI: 3.0–13.0] vs. 7.4 [95% CI: 5.7–9.1] pp). Correspondingly, an increase in the proportion of patients receiving sickness benefits including other health-related benefits was evident around the time of diagnosis.

Conclusion

Overall, we found that Danish patients with essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis, and unclassifiable MPN had slightly impaired labor market affiliation compared with a population of the same age and sex. From two years pre-diagnosis to two years post-diagnosis, we observed a larger reduction in the proportion of patients with MPN working and a greater proportion receiving sickness benefits compared with matched individuals.

Introduction

Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are chronic hematologic malignancies characterized by specific driver mutations leading to hyper-proliferation of myeloid cells and low-grade inflammation [Citation1–3]. The four major MPN subtypes – essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), myelofibrosis (MF), and unclassifiable MPN (MPN-U) – are often associated with a substantial symptom burden, and common disease manifestations include fatigue, abdominal discomfort, and vascular events [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4,Citation5]. Further, compared with the general population, patients with MPNs have a higher prevalence of several comorbidities and secondary cancers [Citation6–12].

A number of studies have found MPN morbidity to precede the time of diagnosis [Citation8,Citation13–16]. For example, Mesa et al. found that almost half (49%) of MF patients and the majority of ET (58%) and PV (61%) patients reported MPN-related symptoms [Citation17] more than one year before diagnosis [Citation16]. Moreover, Enblom et al. observed vascular events in one-fourth of MPN patients preceding diagnosis [Citation14]. Correspondingly, we recently demonstrated that patients with MPNs have increased healthcare resource utilization – including hospitalizations, outpatient consultations, and emergency department visits – within two years before diagnosis [Citation18]. Thus, it seems likely that labor market affiliation of patients with MPNs may be affected negatively by debilitating complications both preceding and following the time of MPN diagnosis.

Three cross-sectional questionnaire studies reported markedly impaired labor market affiliation including reduced work hours, sick leave, disability pension, early retirement, involuntary loss of work, and limited career potential among patients with MPNs, subsequent to their diagnosis [Citation13,Citation16,Citation19]. Moreover, Danish register-based studies demonstrated an increased risk of disability pension and wage-subsidized employment due to permanently reduced work capacity among patients with various hematological malignancies (not including MPNs) compared with the general population [Citation20,Citation21].

Work-life is often an important part of a person’s identity, and although the median age of patients with MPNs is 69 years across subtypes, more than 25% of patients have not reached the age of retirement when diagnosed (interquartile range [IQR]: 57–78 years) [Citation22]. In addition, impaired labor market affiliation has negative personal and societal consequences in terms of reduced income, diminished productivity, and elevated social benefit expenditures. Thus, objective measures of MPN-associated impairment of labor market affiliation are of public health interest. Hence, we aimed to assess labor market affiliation and changes herein pre- to post-diagnosis among patients with MPN compared with matched individuals without MPN.

Methods

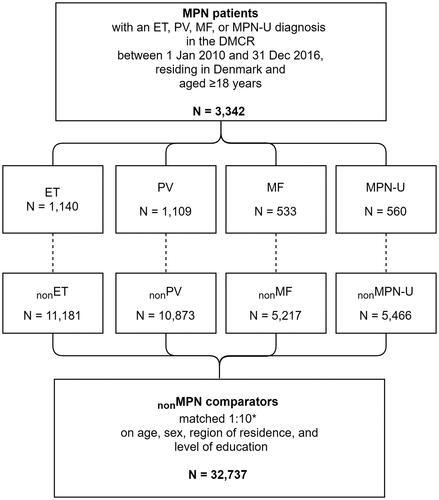

This observational, population-based, matched cohort study was conducted in Denmark, a welfare state with equal rights for all residents to free, tax-supported health care, and social benefits [Citation23]. The study population encompassed four MPN cohorts of patients diagnosed with ET, PV, MF, and MPN-U. Eligible patients were ≥18 years and residing in Denmark at the time of diagnosis. Further, four cohorts of nonMPN comparators (nonET, nonPV, nonMF, and nonMPN-U) were randomly sampled without replacement from the general population. For each patient, up to ten comparators free of MPN were individually matched on sex, age (year of birth), region of residence, and level of education ( and Table S1 in the supplement). We included patients diagnosed between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2016, using the date of MPN diagnosis as the index date (Figure S1). The entire study period covered 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2018; i.e. a pre-diagnosis period of two years and a post-diagnosis period of up to nine years. Follow-up ended at the first occurrence of death, emigration, or end of study on 31 December 2018.

Data from Danish nationwide registries were linked using a unique personal identification number assigned by the Danish Civil Registration System to all Danish residents at birth or immigration [Citation24,Citation25]. Besides information on migration and death (all-cause), the registry holds information on sex, date of birth, and place of residence.

The level of education was obtained from educational data provided by Statistics Denmark [Citation26] and classified according to highest completed education (Table S1).

To characterize the cohorts, we retrieved information on comorbidity using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score. We included in- and outpatient diagnoses within five years prior to the index date according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision codes registered in the Danish National Patient Registry (Table S1) [Citation27,Citation28].

Diagnoses of ET, PV, MF, and MPN-U were identified by the first recorded diagnosis (according to the prevailing World Health Organization [WHO] diagnostic criteria) in the Danish National Chronic Myeloid Neoplasia Registry (Table S1) [Citation29]. This national quality registry contains data such as diagnosis date, type of MPN diagnosis, and clinical and paraclinical assessments.

Data on labor market affiliation was acquired from the DREAM database (Table S2) [Citation30]. This database, established in 1991, registers information on public transfer payments for all Danish citizens. Labor market-related benefits (including unemployment benefits and retirement pensions) and health-related benefits (including disability pensions, sickness benefits, and other health-related benefits) are recorded on a weekly basis. Individuals who were not classified as receiving any transfer payment including retirement pension, were considered self-supporting and classified as working. In addition, individuals receiving State Educational Grants or parental leave pay were classified as working. During the study period, the age for public retirement pension was 65 years. From 1994 to 2007, designated codes for retirement pensions were included in DREAM only for individuals who had received other transfer payments prior to age retirement [Citation30]. We, therefore, supplemented with an indirect derivation, assigning retirement pensions to all individuals who were aged >65 years in 1994 and had no record of transfer payment [Citation30]. Using this approach, >95% of study participants aged >65 at the index date were considered retired, except for the ages 75–86 years in which this proportion varied between 67% and 93%.

Statistical analysis

Frequency (n) with proportion (%) and median with IQR were used to describe the characteristics of patients and comparators (). In addition, median follow-up time and the frequency and proportion of study participants who died or emigrated during follow-up were reported.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population at index date.

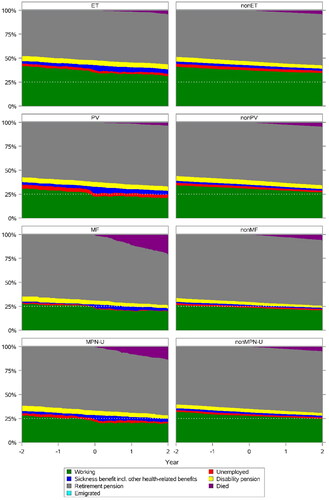

Labor market affiliation was classified as: working, unemployed, or receiving retirement pension, disability pension, sickness benefit, or other health-related benefits (Table S2). We graphically depicted outcome measurements in proportions by week for each cohort from two years before until two years after the time of index (). Moreover, labor market affiliation was assessed cross-sectionally and reported as proportions with 95% confidence interval (CI) ( and ) and frequencies (Tables S4 and S5) for week −104, −52, 52, and 104 relative to the index date and for the week of the index date. Change in labor market affiliation from two years pre-diagnosis to two years post-diagnosis was calculated as absolute difference and reported as percentage point (pp) reduction or increase (i.e. the proportion in week 104 minus the proportion in week −104) with 95% CIs. In our main analyses, we restricted data to two years post-diagnosis, to avoid bias due to substantial proportions of deaths and administrative censoring of patients and comparators after two years of follow-up. To assess labor market affiliation over the entire follow-up, taking deaths and censoring into account, we summarized the proportions of person-time attributable to different categories of labor market affiliation for each year as the number of weeks attributable to the respective outcome measurements divided by the total number of weeks of observation (Table S6). To evaluate changes in labor market affiliation among younger individuals who are less likely to be retired, we conducted a subgroup analysis restricted to individuals younger than 70 years at index date (Figure S2).

Figure 2. Labor market affiliation as proportions by week for each diagnosis group from two years before until two years after diagnosis.

Table 2. Labor market affiliation in proportions pre- and post-diagnosis (cross-sectional), stratified by diagnosis group.

Table 3. Labor market affiliation in proportions at index week (cross-sectional), stratified by diagnosis group.

To comply with data protection regulations, exact cell counts below or equal to five were masked as ’≤5′ and related cell counts were rounded to prevent identification of individuals by back calculation from the total number of individuals in the cohort.

The study was registered by Aarhus University according to Danish and European regulations for data protection (Aarhus University record number 2016-051-000001, #886). Data management and analyses of the pseudonymized data were performed on secured servers at Statistics Denmark using SAS 9.4. According to Danish legislation, registry-based studies does not require approval from an ethics committee nor informed consent from patients.

Results

A total of 3,342 patients with MPN were eligible for inclusion (). The four MPN cohorts consisted of 1,140 patients with ET, 1,109 with PV, 533 with MF, and 560 with MPN-U. The matched comparator cohorts comprised a total of 32,737 nonMPN comparators (11,181 nonET, 10,873 nonPV, 5,217 nonMF, and 5,466 nonMPN-U comparators). The median age was 67 years (IQR: 55–76 years) in patients with ET, 69 years (IQR: 61–77 years) in PV, 73 years (IQR: 66–79 years) in MF, and 72 years (IQR: 63–80 years) in MPN-U (). A smaller proportion of patients (62.5% of ET, 60.2% of PV, 56.5% of MF, and 57.9% of MPN-U) than comparators (75.4% of nonET, 73.2% of nonPV, 67.9% of nonMF, and 71.8% of nonMPN-U) had a baseline CCI score of 0.

The median follow-up time was 2.8 years in patients with MF and MPN-U, while it was 3.6 years in patients with ET and PV (). In nonMPN comparators, the median follow-up ranged from 3.6 to 3.9 years. Two years post-diagnosis, the proportion of deaths was similar in ET and PV patients and comparators (ET: 3.7% vs. 3.7%; and PV: 3.2% vs. 4.2%), while it was elevated in patients with MF (19.7%) and MPN-U (13.4%) compared with nonMF (5.5%) and nonMPN-U (4.6%) (). Beyond year two post-diagnosis, the proportion of person-time attributable to deaths and censoring increased markedly (Table S6). By the end of the study period, the total proportion of deaths was similar among ET (13.8%) and PV (15.6%) patients and comparators (). In contrast, the total proportions of deaths among patients with MPN-U (35.4%) and MF (41.7%) were higher than among nonMPN-U (16.1%) and nonMF (19.3%) comparators.

Labor market affiliation pre-diagnosis

Patients with PV and MPN-U were less likely to be working than their comparators two years pre-diagnosis (PV, 31.0% [95% CI: 28.3–33.7%] vs. 34.3% [95% CI: 33.4–35.2%] and MPN-U, 28.2% [95% CI: 24.5–31.9%] vs. 32.0% [95% CI: 30.7–33.2%]) and one-year pre-diagnosis (PV, 28.9% [95% CI: 26.3–31.6%] vs. 32.5% [95% CI: 31.6–33.4%] and MPN-U, 25.7% [95% CI: 22.1–29.3%] vs. 29.3% [95% CI: 28.1–30.6%]) (). In addition, a larger proportion of PV patients than comparators were unemployed prior to diagnosis (4.2% [95% CI: 3.1–5.4%] vs. 2.7% [95% CI: 2.4–3.0%] two years pre-diagnosis and 3.8% [95% CI: 2.7–4.9%] vs. 2.4% [95% CI: 2.1–2.6%] one-year pre-diagnosis). Further, a larger proportion of MPN-U patients than comparators received disability pension prior to diagnosis (5.2% [95% CI: 3.3–7.0%] vs. 3.9% [95% CI: 3.4–4.4%] two years pre-diagnosis and 5.4% [95% CI: 3.5–7.2%] vs. 3.9% [95% CI: 3.4–4.4%] one-year pre-diagnosis).

Labor market affiliation at the time of diagnosis

At the time of diagnosis, patients were less likely to be working than their comparators (ET, 35.3% [95% CI: 32.5–38.0%] vs. 37.2% [95% CI: 36.3–38.1%]; PV, 22.5% [95% CI: 20.1–25.0%] vs. 30.6% [95% CI: 29.8–31.5%]; and MPN-U, 21.6% [95% CI: 18.2–25.0%] vs. 27.8% [95% CI: 26.6–29.0%]) (). Among all MPN subtypes, the majority of patients and comparators received retirement pensions (52.1–70.5%). Slightly larger proportions of patients (4.1–5.1%) than comparators (3.1–4.7%) received a disability pension. Moreover, larger proportions of patients than comparators received sickness benefit (ET, 3.6% [95% CI: 2.5–4.7%] vs. 1.4%, [95% CI: 1.2–1.6%]; PV, 5.5% [95% CI: 4.2–6.8%] vs. 0.9% [95% CI: 0.7–1.0%]; MF 3.2% [95% CI: 1.7–4.7%] vs. 0.7% [95% CI: 0.4–0.9%]; and MPN-U, 1.3% [95% CI: 0.3–2.2%] vs. 0.9% [95% CI: 0.6–1.1%]).

Changes in labor market affiliation

From two years pre-diagnosis until two years post-diagnosis, the proportion of patients and comparators working consistently decreased. However, a prominent decline appeared among patients with MPN around the time of diagnosis (), yielding a larger decline in patients than comparators working over the four-year period (ET, 10.2 pp [95% CI: 6.3–14.1 pp] vs. 6.8 pp [95% CI: 5.5–8.0 pp]; PV, 9.6 pp [95% CI: 5.9–13.2 pp] vs. 7.4 pp [95% CI: 6.2–8.7 pp]; MF, 8.1 pp [95% CI: 3.0–13.2 pp] vs. 5.8 pp [95% CI: 4.2–7.5 pp]; and MPN-U, 8.0 pp [95% CI: 3.0–13.0 pp] vs. 7.4 pp [95% CI: 5.7–9.1 pp]) (). Correspondingly, a slight increase in MPN patients receiving sickness benefits was evident around the time of diagnosis and one-year post-diagnosis – and in patients with ET and PV, up to two years post-diagnosis (ET, 1.8 pp [95% CI: 0.2–3.3 pp] and PV, 1.4 pp [95% CI: 0.0–2.8 pp]). In contrast, the proportion of comparators receiving sickness benefits remained unchanged. The change in proportions being unemployed or receiving disability pension was similar between patients and comparators. The proportions receiving retirement pension increased by 4.5 pp (95% CI: 0.4–8.6 pp) in ET patients, 4.6 pp (95% CI: 3.3–6.0 pp) in nonET comparators, 6.2 pp (95% CI: 2.2–10.3 pp) in PV patients, and 5.1 pp (95% CI: 3.8–6.4 pp) in nonPV comparators from two years pre-diagnosis until two years post-diagnosis. Concurrent with increasing mortality, a reduction in the proportion of MF and MPN-U patients receiving retirement pensions was observed.

Results from the subgroup analysis restricted to study participants younger than 70 years (Figure S2) supported the results regarding changes in labor market affiliation from the main analysis.

Discussion

This study presents the first register-based assessment of labor market affiliation of MPN patients and matched comparators without MPN by utilizing data from a Danish nationwide cohort of 3,342 MPN patients and 32,737 matched individuals.

Labor market affiliation pre-diagnosis

We observed slightly impaired labor market affiliation of MPN patients compared with matched individuals in the years prior to diagnosis. These findings correspond with previous studies reporting that MPN symptoms [Citation8,Citation13,Citation16], vascular complications [Citation14], and increasing healthcare resource utilization [Citation15,Citation18] often precede the time of MPN diagnosis. Most notably, we found patients with PV and MPN-U were less likely to be working and more likely to be unemployed (PV) and to receive disability pensions (MPN-U) than their comparators.

Changes in labor market affiliation

Working

We found that fewer MPN patients than nonMPN comparators were working at the time of diagnosis with the most prominent discrepancy between PV and MPN-U patients and comparators. Further, across all MPN subtypes, a larger decline in the proportion of working was observed among MPN patients than among their respective comparators around the time of diagnosis and during follow-up. Given the matched design, these findings are most likely explained by increased overall morbidity in MPN patients. This is supported by the difference observed in CCI score between patients and comparators at baseline. No comparable register-based studies on MPN patients’ labor market affiliation have been published to date. However, impaired work ability has been described in register-based studies of hematological cancers, showing an increased need for wage-subsidized employment [Citation21] and disability pension [Citation20] and a low (50%) return to work after autologous stem cell transplantation [Citation31]. Moreover, in agreement with our findings, three questionnaire studies found impaired work ability after an MPN diagnosis [Citation13,Citation16,Citation19]. In the Living with MPNs survey half of the respondents reported a negative change in employment status due to their MPN disease [Citation19].

Sickness benefit

Regardless of MPN subtype, larger proportions of MPN patients than nonMPN comparators received sickness benefits at the time of diagnosis. Further, compared with two years before diagnosis, the proportion of patients receiving sickness benefits remained higher after one (all patients) and two (patients with ET and PV) years following diagnosis, while it was unchanged in the comparator cohorts; thereby implying an association with MPNs and/or MPN-related complications. Compared with the proportion receiving sickness benefits two years post-diagnosis in the present study (2.1–4.6%), a slightly smaller proportion of MPN patients in the international MPN Landmark survey from Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, Italy, and United Kingdom was on sick leave (1–3%) [Citation13]; likely reflecting differences in social benefit systems.

We found the most pronounced difference in sickness benefits between PV patients and their comparators. This was unexpected as MF is considered the most severe MPN subtype, and sick leave episodes of less than 14 days are registered in DREAM only if the person has a chronic disease with expected increased sick leave over time [Citation30]. In addition, MF patients have reported the highest frequency of sick leave in questionnaire studies [Citation13,Citation16,Citation19]. However, a larger proportion of PV than MF patients were eligible for sickness benefits due to lower median age and lesser likelihood of receiving retirement pension. Moreover, the comparison of labor market affiliation between MPN subtypes is influenced by the proportion of deaths in each group. Hence, the proportion receiving sickness benefits was found to be higher when restricted to patients of younger age.

The reasons for MPN patients’ sick listings are not well-understood. In chronic myeloid leukemia, persistent adverse drug reactions and comorbidity have been reported to affect employment [Citation32], and it is likely that adverse drug effects [Citation33] also influence labor market affiliation in our study population.

Disability pension and health-related benefits

At the time of diagnosis, slightly larger proportions of MPN patients than nonMPN comparators received a disability pension. Among both patients and comparators, this proportion declined from two years before to two years after diagnosis. No substantial differences were observed for health-related benefits including wage-subsidized employment. We speculate that the lack of translation of MPN morbidity into substantial labor market affiliation impairment reflects limited access to disability pension and wage-subsided employment before a chronic diagnosis with a permanently reduced work capacity has been established [Citation20,Citation21]. Two prior Danish register-based studies reported that patients with hematologic malignancies were more often granted disability pensions and wage-subsidized employment than age- and sex-matched comparators [Citation20,Citation21]. However, these studies did not include MPN patients, and the diverging results are likely affected by the shorter follow-up time in our study and the higher median age of MPN patients, making disability pension and wage-subsidized employment less applicable.

Unemployment

Throughout the study, few participants (≤4.2%) were unemployed with no marked differences between MPN patients and nonMPN comparators, except for a higher proportion of unemployment in PV patients than nonPV comparators. In comparison, the US MPN Landmark survey reported that among patients with MPNs, 11–31% had voluntarily and 4-5% had involuntarily terminated their jobs due to MPN [Citation16]. The higher median age of Danish MPN patients and different national social benefit systems and unemployment rates may contribute to the discrepancies.

Retirement pension

As expected, the majority of MPN patients and comparators received retirement pensions at the index date. From pre-diagnosis to post-diagnosis, there was a slightly larger increase in the proportion of patients with ET and PV than comparators receiving retirement pensions. A contributing factor may be that patients with MPN-related symptoms and complications were less likely to continue working beyond retirement age. This speculation is supported by 8% of international MPN Landmark survey participants and 18% of Living with MPNs survey participants reporting ’early retirement due to MPN’ [Citation13,Citation19]. In contrast, the proportion of MF and MPN-U patients receiving retirement pensions decreased slightly over time, while remaining unchanged among comparators. This is probably best explained by the higher mortality among MF and MPN-U patients than comparators.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study was the nationwide design, including all Danish MPN patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2016, extending the generalizability of our findings to countries with similar healthcare systems and labor markets. Moreover, the matched design enabled us to compare labor market affiliation of patients with MPNs with matched individuals without MPN. Finally, the use of data from high-quality Danish nationwide registers, linked on an individual level, ensured almost complete follow-up [Citation23,Citation25,Citation27–30,Citation34,Citation35].

This study also has some limitations. First, some patients could be misclassified according to MPN subtype as differentiation can be challenging, and MPNs can evolve over time. However, in Denmark, all MPN patients are diagnosed in hematological departments according to the WHO criteria with mutation analysis and bone marrow examination, thus increasing the diagnostic certainty. Second, as no code for working exists in DREAM, the proportion of individuals working may be overestimated, because we assumed that individuals below retirement age, who did not receive any public transfer payment, were working. However, we expect this misclassification to be non-differential as it applied equally to patients and comparators. In addition, non-differential misclassification cannot be ruled out in our assignment of retirement pension, because the applied algorithm did not capture data on retirement pension for 7–33% of participants aged 75–86 years at index date. However, this pertained to a limited proportion of the entire study population. Third, as comorbidity assessed by the CCI score may include medical conditions related and un-related to MPN, we were not able to differentiate between impairments of labor market affiliation associated with MPN or co-existing conditions. Lastly, as MPNs are rare diseases, the numbers in some strata were too small to report and yielded estimates with relatively wide confidence intervals.

Conclusion

Overall, we found that Danish patients with ET, PV, MF, and MPN-U had slightly impaired labor market affiliation compared with a population of the same age and sex. From two years pre-diagnosis until two years post-diagnosis, we observed a larger reduction in the proportion of patients with MPN working and a greater proportion receiving sickness benefits compared with matched individuals without MPN. These results highlight that in all MPNs, even ET, which is considered relatively indolent, some patients lose contact with the labor market during the course of the disease.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (165.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (543.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Danish hematologists for their continued efforts in reporting MPN data to the Danish National Chronic Myeloid Neoplasia Registry.

Disclosure statement

Novartis funded the work done by the employees at Aarhus University. A.K., C.F.C., E.M.M., and L.S.S.: employees at Aarhus University/Aarhus University Hospital. A.S. and B.P.: employees at Novartis. H.C.H.: consultant for Novartis. All authors declare no personal conflicts of interests.

Data availability statement

Data presented in this study were obtained from Danish registries and handled remotely at secured servers at Statistics Denmark. Owing to the guidelines by Statistics Denmark, the authors are not allowed to share individual-level data. Anonymized data (including counts reported as '≤5' persons) are shared in the manuscript. Other researchers who fulfil the requirements set by the data providers could obtain similar data.

References

- Spivak JL. Myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2168–2181. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1406186.

- Nangalia J, Green AR. Myeloproliferative neoplasms: from origins to outcomes. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017(1):470–479. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.470.

- Hasselbalch HC, Bjørn ME. MPNs as inflammatory diseases: the evidence, consequences, and perspectives. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:102476–102416. doi:10.1155/2015/102476.

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the world health organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544.

- Geyer HL, Dueck AC, Scherber RM, et al. Impact of inflammation on myeloproliferative neoplasm symptom development. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:284706–284709. doi:10.1155/2015/284706.

- Bak M, Jess T, Flachs EM, et al. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Cancers. 2020;12(9):2700. doi:10.3390/cancers12092700.

- Bak M, Sørensen TL, Flachs EM, et al. Age-related macular degeneration in patients with chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(8):835–843. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2011.

- Frederiksen H, Szépligeti S, Bak M, et al. Vascular diseases in patients with chronic myeloproliferative Neoplasms–impact of comorbidity. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:955–967. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S216787.

- Christensen AS, Møller JB, Hasselbalch HC. Chronic kidney disease in patients with the philadelphia-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leuk Res. 2014;38(4):490–495. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2014.01.014.

- Frederiksen H, Farkas DK, Christiansen CF, et al. Chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and subsequent cancer risk: a Danish population-based cohort study. Blood. 2011;118(25):6515–6520. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-04-348755.

- Landtblom AR, Bower H, Andersson TML, et al. Second malignancies in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: a population-based cohort study of 9379 patients. Leukemia. 2018;32(10):2203–2210. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0027-y.

- Barbui T, Ghirardi A, Masciulli A, et al. Second cancer in philadelphia negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN-K). a nested case-control study. Leukemia. 2019;33(8):1996–2005. doi:10.1038/s41375-019-0487-8.

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653–1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y.

- Enblom A, Lindskog E, Hasselbalch H, et al. High rate of abnormal blood values and vascular complications before diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(5):344–347. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.03.009.

- Bankar A, Zhao H, Iqbal J, et al. Healthcare resource utilization in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a population-based study from Ontario, Canada. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(8):1908–1919. doi:10.1080/10428194.2020.1749607.

- Mesa R, Miller CB, Thyne M, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a significant impact on patients’ overall health and productivity: the MPN landmark survey. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2208-2.

- Scherber R, Dueck AC, Johansson P, et al. The myeloproliferative neoplasm symptom assessment form (MPN-SAF): international prospective validation and reliability trial in 402 patients. Blood. 2011;118(2):401–408. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-328955.

- Christensen SF, Svingel LS, Kjaersgaard A, et al. Healthcare resource utilization in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: a Danish nationwide matched cohort study. Eur J Haematol. 2022;109(5):526–541. doi:10.1111/ejh.13841.

- Yu J, Parasuraman S, Paranagama D, et al. Impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms on patients’ employment status and work productivity in the United States: results from the living with MPNs survey. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):420. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4322-9.

- Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Andersen NT, et al. Risk of disability pension for patients diagnosed with haematological malignancies: a register-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(6):724–734. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2013.875625.

- Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Nielsen B, et al. Wage-subsidised employment as a result of permanently reduced work capacity in a nationwide cohort of patients diagnosed with haematological malignancies. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):743–749. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2014.999871.

- Roaldsnes C, Holst R, Frederiksen H, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms: trends in incidence, prevalence and survival in Norway. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(1):85–93. doi:10.1111/ejh.12788.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563–591. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S179083.

- Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–25. doi:10.1177/1403494810387965.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549. doi:10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3.

- Statistics Denmark [Internet]. Denmark: Statistics Denmark [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/emner/uddannelse-og-forskning/befolkningens-uddannelsesstatus/befolkningens-hoejst-fuldfoerte-uddannelse.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. CLEP. 2015;7:449–490. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S91125.

- Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based danish national registry of patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):83. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-83.

- Bak M, Ibfelt EH, Stauffer Larsen T, et al. The Danish national chronic myeloid neoplasia registry. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:567–572. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S99462.

- Hjollund NH, Larsen FB, Andersen JH. Register-based follow-up of social benefits and other transfer payments: accuracy and degree of completeness in a Danish interdepartmental administrative database compared with a population-based survey. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(5):497–502. doi:10.1080/14034940701271882.

- Arboe B, Olsen MH, Goerloev JS, et al. Return to work for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:321–329. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S134603.

- De Barros S, Vayr F, Despas F, et al. The impact of chronic myeloid leukemia on employment: the french prospective study. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(3):615–623. doi:10.1007/s00277-018-3549-5.

- Mascarenhas J, Kosiorek HE, Prchal JT, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of interferon-α vs hydroxyurea in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2022;139(19):2931–2941. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012743.

- Stapelfeldt CM, Jensen C, Andersen NT, et al. Validation of sick leave measures: self-reported sick leave and sickness benefit data from a danish national register compared to multiple workplace-registered sick leave spells in a danish municipality. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):661. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-661.

- Norgaard M, Skriver MV, Gregersen H, et al. The data quality of haematological malignancy ICD-10 diagnoses in a population-based hospital discharge registry. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14(3):201–206. doi:10.1097/00008469-200506000-00002.