ABSTRACT

This article aims to test whether local governments can enhance the elected councillors’ perceived political leadership by changing the institutional design that conditions their ability to define problems that call for collective action, design policy solutions and mobilise support for their implementation. The study draws on new research on political leadership and institutional design and data from surveys conducted in Denmark and Norway. The analytical framework distinguishes between four different but overlapping institutional design strategies, and the main finding is that institutional designs aiming to enhance executive, collective or distributive political leadership are associated with an increase in perceived political leadership, whereas – surprisingly – institutional designs aiming to enhance interactive political leadership are not. Upon closer inspection, however, the impact of interactive institutional designs on political leadership seems to be conditioned on whether the power relation between politicians and administrators is balanced or unbalanced.

1. Introduction

Elected politicians face the formidable challenge of solving complex societal problems and delivering high-quality public services in turbulent times in which governments suffer from dire fiscal constraints and power is dispersed across organisations, sectors and levels. Political mistrust results when politicians fail to deliver policy solutions and public services that meet citizens’ growing expectations (Edelman Citation2017). The lack of trust in government provide ideal conditions for right-wing populism that undermines democratic values and institutions (Stoker and Hay Citation2017).

One way of reversing this unfortunate trend is to enhance the democratic political leadership of elected politicians so that people view their elected representatives as responsive to their needs, capable of solving societal problems, and able to spearhead the development of society. To that end, this article explores whether and how deliberate attempts at changing the institutional conditions for the exercise of local-level democratic political leadership can help build a robust and responsive political leadership that enhances democratic legitimacy by solving pressing problems while respecting the democratic rules of the game. As such, we analyse the impact of new institutional designs on how elected councillors perceive their exercise of political leadership. The overall hypothesis is that tinkering with the design of local political institutions will help to enhance the political leadership of local councillors so that they can solve problems and deliver solutions that meet citizens’ expectations.

There is an urgent need to enhance the political leadership of local councillors. The councillors are ‘recreational’ politicians who spend most of their limited time processing cases in permanent political committees, thus leaving little time for policy development and problem-focused engagement with local community actors. In addition, they are often overpowered by full-time civil servants, who seem to prefer the status quo rather than testing new political solutions (Svara Citation2001). Finally, many councillors do not perceive themselves as political leaders (Karsten and Hendriks Citation2017), even despite expectations that they carry out core political leadership functions, such as defining policy problems and designing and mobilising support for new solutions (Tucker Citation1995).

Local governments are trying to enhance the political leadership of the councillors by introducing new institutional designs aimed at providing adequate time and opportunities for policy development (Berg and Rao Citation2005; Hertting and Kugelberg Citation2017; Sørensen and Torfing 2018). Alexander defines institutional design as ‘the devising and realization of rules, procedures, and organizational structures that will enable and constrain behaviour and action so as to accord with held values, achieve desired objectives, or execute given tasks’ (Alexander Citation2005, 213). This definition encompasses the accounts of institutional design held by different strands of the new institutionalism (Peters Citation2012).

This article aims to test whether local governments can enhance political leadership by changing the institutional design that conditions the ability of elected councillors to exercise political leadership. The study is based on surveys conducted in Denmark and Norway as part of a large research project. The theoretical framework for the analysis distinguishes between four different but overlapping institutional design strategies, and the main finding is that institutional designs aiming to enhance executive, collective or distributive political leadership are associated with an increase in perceived political leadership, whereas – surprisingly – institutional designs aiming to enhance interactive political leadership are not. Upon closer inspection, however, the impact of interactive institutional designs seems to be conditioned on whether the power relation between politicians and administrators is balanced or unbalanced.

The article is structured as follows: First, we present the theoretical framework focusing on the concepts of political leadership and institutional design and the reasons to expect that the latter may have a positive impact on the former. Next, we briefly account for the collection and analysis of the data. This brings us to the presentation of the empirical results from the survey analysis, which are interpreted and discussed in the subsequent section. Finally, the conclusion summarises the central points before reflecting on future research avenues.

2. Theorising the institutional design of political leadership

As already hinted at in the introduction, there is a growing need to adjust local political institutions in order to enhance the political leadership of local councillors in ways that meet local citizens’ expectations to their elected representatives’ ability to set the agenda, solve urgent problems and deliver high-quality services. Local political organisations tend to occupy elected councillors with specialised case-processing in permanent political committees that mirrors the administrative division of labour, thus enhancing the councillors’ legal expertise at the expense of a growing tunnel view. They turn the local councillors into policy-takers by placing policy development in the hands of strong, professional civil servants who are exercising strategic management by initiating and formulating large numbers of policy recommendations. Finally, they tend to isolate the elected councillors from local community actors, including increasingly competent and assertive citizens (Svara Citation2001; Peters and Pierre Citation2004; Dalton and Welzel Citation2014; Kjær and Opstrup Citation2016; Invernizzi-Accetti and Wolkenstein Citation2017; Torfing and Ansell 2017). New Public Management aimed to strengthen the political leadership of elected councillors by emphasising their crucial role in a system of goal- and framework-steering, which was intended to ensure efficient service delivery (Barber Citation2007). However, the formulation of abstract policy goals and general service standards is a poor substitute for active involvement in the development of new policy and governance solutions that became the prerogative of executive civil servants who were portrayed as strategic managers and given responsibility for driving public sector change (Sørensen and Torfing 2013).

This bleak diagnosis has fostered growing interest in how new institutional designs can help to enhance local political leadership (Helms Citation2012; Elgie Citation2014). A growing number of studies bear witness to the proliferation of local institutional reforms aimed at strengthening political leadership through the development of new institutional designs (Smith Citation2009; Newton and Geissel Citation2012; Grönlund, Bächtiger, and Setälä Citation2014; Reuchamps and Suiter Citation2016; Hertting and Kugelberg Citation2017; Sørensen and Torfing 2018). A recent study of Danish and Norwegian municipalities confirms that institutional reforms are widely used to reform local political institutions to improve the conditions for the exercise of political leadership (Bentzen, Lo and Winsvold 2019). With a few exceptions (Elcock Citation2001; Mouritzen and Svara Citation2002; Berg and Rao Citation2005), however, recent research has paid scarce attention to the key question of how the introduction of new institutional designs conditions local political leadership.

Institutional design

While local councillors more or less skilfully utilise institutional arenas, procedures and rules in their work to build alliances, influence decisions and secure re-election, the political institutions are also likely to shape and influence the local politicians’ overall ability to exercise political leadership defined as the ability to set the agenda, give direction to new solutions and mobilise support for their implementation (Vabo Citation2000; Berg and Rao Citation2005; Bäck Citation2005; Elgie Citation2014; Tucker Citation1995). This renders the relationship between politicians and political institutions a two-way street.

Institutions are here defined in terms of the rules, procedures, routines, norms, values, and forms of knowledge that enable a stable reproduction of political leadership practices by prescribing a particular logic of appropriate action (March and Olsen Citation1995). Institutional reforms are defined as purposeful attempts to change to such rules, procedures, routines, norms, values or forms of knowledge in order to affect the behaviour of key actors and bringing about desired results, including the enhancement of political leadership. Institutional reforms are not always fully implemented, but even a partial implementation may give rise to new institutional designs that seek to enable and constrain social and political action in accordance with particular values, objectives or organisational needs (see Goodin Citation1998; Fung Citation2003; Alexander Citation2005).

Changes in the design of formal political institutions do not necessarily affect the enactment of political leadership in the manner intended by reformers. Although some scholars find that institutional design may enhance leadership performance (Greasley and Stoker Citation2008), the impact of institutional reforms is not linearly determined by the intentions behind the changes (Peters Citation2012). Hence, we cannot assume that institutional designs intended to enhance political leadership will necessarily have the desired effect, as the assumptions implicit to the change theory may be ill-founded or may not hold in the face of unacknowledged reform conditions.

Political leadership

In liberal democracies, political leadership is essentially about formulating and achieving political goals while securing support from critical followers (Nye Citation2008). The notion of political leadership is shaped by and consequently varies with institutional, cultural and historical context (Masciulli, Molchanov, and Knight Citation2009). Still, three key political leadership functions, emphasising the role of politicians in agenda setting, solution design and the mobilisation of support, are found recurrently across a number of definitions (Tucker Citation1995; Nye Citation2008; Sørensen Citation2020). Agenda setting involves offering a political interpretation of the situation and identifying the problems, challenges and opportunities that call for collective action (Leach and Wilson Citation2002; Greasley and Stoker Citation2008; Kellerman Citation2015). Designing solutions to the identified problems and challenges involves the discovery of the needs behind the demands, visionary goal-setting, creative problem-solving and feasibility tests (Kotter and Lawrence Citation1974; Tucker Citation1995; Leach and Wilson Citation2002; Burns Citation2004; Gissendanner Citation2004). Finally, a third central function of political leadership is mobilising support for new solutions to ensure proper implementation and consolidation (Kotter and Lawrence Citation1974; Svara Citation1990, Citation1994; Masciulli, Molchanov, and Knight Citation2009).

The advantage of this definition of political leadership is that it allows for an understanding of political leadership as a set of functions that are not exclusively reserved for democratically elected politicians. Other relevant actors, such as community leaders, leaders of social and political movements, charismatic business leaders or people from various NGOs, may also perform important political leadership functions by contributing to agenda setting, solution design and resource mobilisation (Uhl-Bien and Carsten Citation2016; Torfing, Sørensen and Bentzen 2019).

That said, elected politicians are obviously expected to play a pivotal role in the exercise of political leadership given that the election process bestows a democratic mandate upon them to govern on behalf of the people. Nevertheless, there is no guarantee that elected councillors will undertake the core functions that defines the exercise of political leadership. Structural and institutional conditions (or lack of knowledge, skills, commitment, ambition and time) may prevent them from engaging in the definition of pressing societal problems, developing and advocating for particular solutions, or generating support for their implementation; or only do so sporadically and with limited impact on the development and realisation of public policy (Torfing, Sørensen and Bentzen 2019).

Institutional designs aimed at spurring different types of political leadership

The political institutions that channel and regulate the exercise of political leadership are typically shaped by ideas about representative or participatory democracy (Leach and Wilson Citation2002). While representative democracy ideally depicts elected politicians as sovereign and accountable political leaders (Haus and Sweeting Citation2006; Kane, Patapan, and ’T Hart Citation2009), participatory democracy ideally depicts political leaders as convenors and facilitators of broad-based public debates involving relevant and affected actors – including citizens, neighbourhoods and civil society organisations – from outside the elected assembly (Sørensen Citation2006; Koppenjan, Kars, and van der Voort Citation2011; Torfing and Ansell 2017). However, the crude categories of representative vs. participatory democracy can be further nuanced in accordance with different democratic ideals regarding power dispersion. Thus, representative institutional designs may either support executive or collective political leadership, while participatory institutional designs may either enhance distributive or interactive political leadership (Bentzen, Lo and Winsvold 2019).

Institutional designs aiming to enhance political leadership within the broader framework of representative democracy may seek to strengthen the role of the executive political leadership – the mayor and members of the executive (finance) committee – at the apex of government (Esaiasson Citation2011), either through the direct election of the mayor, appointment of special policy advisors to the mayor, or delegation of political power to the executive committee. The argument in favour of such designs would be that political power is concentrated in the hands of a competent executive group of elected politicians led by the mayor, who should be given ample opportunity to drive change and enhance public value creation.

Alternatively, political power may be dispersed among the collective group of elected politicians. In the Scandinavian countries, local government has traditionally been characterised by such dispersion through practices of political negotiation, coalition building and the delegation of power to permanent political committees in which politicians from the political majority and opposition work together to find appropriate solutions. The argument in favour of such designs is that power-sharing within the elected council fosters a broad ownership of political solutions that enhances the likelihood that they are passed by the elected assembly, continuously implemented across elections and generate the desired societal impact.

In sum, institutional designs aiming to strengthen representative democratic leadership may either aim to enhance executive political leadership by concentrating political power in the hands of executive political leaders and giving them opportunity to lead at the apex or aim to enhance a collective political leadership that disperses power among all the elected councillors (Hendriks and Karsten Citation2014).

Participatory political leadership may be defined as a leadership style where leaders are assumed to increase their power by dispersing and sharing it (Svara Citation1990). This ideal of political leadership has experienced an upsurge in recent decades, often referring to the growing need for politicians to get input and mobilise resources from various groups of citizens and stakeholders in order to enhance public innovation and be able to provide costly public services (Leach and Wilson Citation2002; Morrell and Hartley Citation2006; Hartley, Sørensen and Torfing 2013; Sørensen and Torfing 2016; Torfing and Ansell 2017).

Institutional designs aiming to enhance political leadership through the expansion of participatory forms of democracy aim to involve citizens beyond the regular visit to the ballot box (Greasley and Stoker Citation2008; Hendriks and Karsten Citation2014). Participatory ideals argue that citizen participation generates new knowledge and ideas, mobilises resources and builds ownership of new solutions. Citizen participation may not only assist politicians in creating more well-informed and perhaps even innovative solutions, but also creates followership, political support and practical engagement that helps to secure implementation (Smith Citation2009). Hence, participatory models of democracy may inform new institutional designs by facilitating the sharing of knowledge and power, thereby enhancing input and output legitimacy (Fung and Wright Citation2003; Chambers Citation2006; Haus and Sweeting Citation2006).

Political leadership based on active and empowered participation may distribute decision-making power to citizens who get to spend public money on projects they themselves have formulated and selected (Gronn Citation2002; Bentzen, Lo and Winsvold 2019). Since the spectacular experiment with participatory governance in Porto Allegro (Baiocchi Citation2001), we have seen scores of local experiments with participatory budgeting that involve citizens in solving local problems and prioritising public tasks and resources. At the ‘sub-local’ level, there have also been experiments with publicly supported neighbourhood councils aimed at empowering citizens to solve the problems they encounter in their daily lives in dialogue with the city council (Jun Citation2007). The political leadership argument in favour of such experiments may be that they alleviate the decision-making burden of elected politicians by delegating decisions to citizens and local communities, thus allowing them to focus their limited time and energy on more strategic political decisions while avoiding blame for governance failures.

Alternatively, elected policies may invite citizens and local stakeholders to participate in joint policy discussions and engage in collaborative interaction, mutual learning and creative problem-solving that might result in policy recommendations, which the municipal council subsequently discusses, amends and endorses (Sørensen and Torfing 2016; Hendriks Citation2016). Such an interactive design strategy may help bring the politics out to the citizens – and citizens into politics (Stoker Citation2016).

In sum, institutional designs aiming to enhance political leadership in the context of participatory democracy may either lead to the expansion of a distributive political leadership by means of delegating political power to citizens and local communities or an interactive political leadership, where elected politicians develop policy solutions together with citizens and relevant stakeholders.

provides an overview of the four different types of political leadership that new institutional designs resulting from institutional reforms may support. The expected correlations with perceived political leadership is summed up in the last column, and elaborated in the below paragraph.

Table 1. Types of political leadership supported by new institutional designs.

A new institutional design may be introduced in order to support a particular form of political leadership, but several designs may be combined in an institutional reform. As such, the different forms of political leadership defined in may not only compete, but also co-exist.

How institutional reforms impact political leadership: hypotheses

While there might be reason to believe that carefully chosen institutional designs may help to enhance particular types of political leadership, there is often a long-stretched chain of cumulative causation connecting institutional rules, norms and procedures with new political roles and practices, and finally new experiences with exercising political leadership. Delayed and uncertain effects make it difficult to clearly discern the impact of institutional design on political leadership. Moreover, the room for exercising political leadership is influenced by other factors that are difficult to control for (e.g. political culture, attitudes towards change, trust between councillors or between councillors and administration etc.) but may counteract the intended result of new institutional designs. Hence, the measurable effect is expected to be weak as well as uncertain.

With that in mind, we hypothesise that the introduction of institutional designs aimed at empowering either one or more executive political leaders or enhancing the collective ability of the elected councillors to discuss policy decisions will have a positive impact on how the elected councillors perceive their exercise of political leadership. The political empowerment of either executive political leaders or the councillors as a political collective is likely to enhance their ability to perform core political leadership functions. The positive impact of new institutional designs may be slightly stronger for collective political leadership, since the elected councillors will all benefit from these designs and not only the executive politicians. Conversely, elected politicians belonging to the political majority may tend to see a strong mayor or executive political leadership as exercising political leadership on their behalf.

When it comes to the hypothesised impact of distributive and interactive institutional designs, our expectations are more mixed. If we begin with distributive political leadership designs, there is reason to expect a positive impact on perceived political leadership since the delegation of political competence to local citizens and neighbourhoods allows the elected councillors to concentrate their time and energy on strategic policy issues and helps them to avoid taking all the blame for the governance decisions for which citizens have had responsibility. At the same time, there is reason to believe that elected politicians may find that passing political decision-making power to local actors – even if merely a matter of deciding how to spend a small budget for new playgrounds or making plans for a new park in the city centre – undermines their political leadership. As such, we are curious to see whether the impact of distributive political leadership designs on perceived political leadership is positive or negative.

Turning to the impact of interactive political leadership designs, there are two equally sound hypotheses. We might hypothesise that designs promoting a sustained interaction with citizens and local stakeholders will provide valuable inputs that will enable the elected councillors to better understand the policy problems at hand, inspire them to design new and better solutions, and muster support for their implementation (Torfing and Ansell 2017; Sørensen and Torfing 2019a). However, we might also suspect that the involvement of citizens and stakeholders in joint decision-making processes may generate some opposition amongst the elected politicians and make them feel that they are losing political power to unelected actors. Here, we should bear in mind that interactive political leadership institutionalises a new kind of power-sharing whereby politicians are not simply making solutions for the people but with the people (Neblo, Esterling, and Lazer Citation2018).

To further complicate our expectations, we suspect that the impact of both distributive and interactive political leadership designs depends on the relative balance between politicians and administrators that reflects the underlying politics-administration dichotomy.Footnote1 Local councillors typically worry about or regret losing political power to civil servants who are often better educated, more experienced and employed as full-time professional administrators. But the politician‒administrator relationship is more complex than that. According to Svara (Citation2001), a high degree of administrative independence combined with a low degree of political control leads to administrative dominance, whereas a low degree of administrative independence combined with a high degree of political control leads to political dominance. A mutually respectful balance between administrators and politicians is obtained if there is a medium-to-high degree of independence and a medium‒high degree of political control. We hypothesise that a positive impact of distributive and interactive political leadership designs on perceived political leadership requires a balanced relationship, where politicians feel politically empowered and in control of policy development while at the same time they can count on the administrative support from civil servants with considerable professional integrity. By contrast, an imbalance between politicians and administrators may either make power-sharing with societal actors less appealing because the politicians feel disempowered already or because they cannot rely on support from the administration to facilitate and orchestrate the participation of local citizens and neighbourhoods.

3. Cases and method

Before presenting the empirical results, let us briefly account for our selection of case countries and the collection and analysis of data.

Case selection and presentation of case countries

Denmark and Norway are ideal, ‘most likely’ cases for studying variations of institutional design reforms aiming to enhance political leadership (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). The Nordic countries are generally recognised for efficient, well-managed, high-quality public sectors (Greve, Rykkja, and Lægreid Citation2016) together with a high degree of political devolution that allows for comprehensive local autonomy, which enables local governments to develop and test new institutional designs as long as they conform with the rules for the local political organisation specified by the respective Local Government Acts (Ladner, Keuffer, and Baldersheim Citation2016). Moreover, Denmark and Norway are relatively similar countries – both unitary states with ambitious welfare states, where the municipalities are core welfare providers (Rose and Ståhlberg Citation2005). The municipalities are run by local councils that are democratically elected every fourth year. These councils appoint the mayor and form permanent political committees that involve the councillors in sector-specific decision-making and the preparation of council decisions. The mayor presides over the executive committee, which bears the political responsibility for the economy and budget.

Only the relationship between politicians and administrators is somewhat differently regulated in the two countries. As the de jure leader of the administrative organisation, Danish mayors have more extensive formal powers and responsibilities than their Norwegian counterparts (Sletnes Citation2015). The Norwegian mayor, however, has considerable informal powers, partly due to the institutionalised contact between the political and administrative systems: the so-called ‘hourglass model’ (Mikalsen and Bjørnå Citation2015). In practice, this means that the contact between the political and administrative side in the municipal organisation is largely restricted to the mayor and chief administrator. The ideal of a relatively clear-cut separation of politics and administration has also been dominant in Denmark but has been applied much more pragmatically, resulting in a more collaborative relation between political leaders and administrative staff (Christensen, Christiansen, and Ibsen Citation2011).

The 422 Norwegian municipalities have on average about 12,000 citizens, whereas the average population of the 98 Danish municipalities is approximately 57,000. This means that the administrative resources in the local municipalities are expectedly less specialised in Norway than in Denmark, as the municipalities are much smaller.

Methods for data collection and analysis

Our study focusses on Danish and Norwegian local governments (commonly referred to as municipalities or ‘kommuner’) that are run by a mayor who is appointed by, but also leads the elected councils and characterised by high degree of political devolution, large responsibilities for public services, and an above average size compared to municipalities found in Southern Europe (although some Norwegian municipalities are very small). Although the mayor is not directly elected, the local political system in Denmark and Norway resembles the weak-mayor form of the US mayor-council system as the mayor has limited executive powers outside the elected council.

The local councillors’ perceptions of political leadership was assessed through nationwide online surveys targeting Norwegian and Danish elected municipal councillors. The surveys were distributed via email in the autumn of 2018 to the entire population of local councillors with valid email addresses (9,196 of the 10,621 local councillors in Norway and all 2,470 councillors in Denmark). After three reminders, 3,387 of the Norwegian and 718 of the Danish councillors had replied, which gives satisfactory response rates of 40 and 29%, respectively.

Data on institutional designs that may support the exercise of political leadership are drawn from online surveys distributed to the administrative CEOs of all 422 Norwegian and 98 Danish municipalities, who were instructed to draw on their administrative secretaries for the municipal council if need be. In Norway, a reply was obtained from 74% of the municipalities, whereas the response rate was 86% in Denmark.

Only political respondents from municipalities that had responded to the administrative survey were included in the analysis of political leadership, reducing the numbers of respondents to 2,500 Norwegian and 550 Danish councillors. These figures were further reduced by some of the questions in both questionnaires being left unanswered. The net sample sizes were 2,300 and 499, respectively.

‘Political leadership’ is construed as an additive index consisting of items measuring all three elements of political leadership, as defined in the theory section: 1) perceived contribution to setting the political agenda; 2) perceived contribution to identifying policy solutions; and 3) and perceived ability to mobilise support for new solutions. Since the reforms are aimed at enhancing political leadership both in relation to the citizens and amongst the elected politicians, the mobilisation of support is represented by two items: the ability to generate support from the citizens and local community and the ability to mobilise gains within the respective party groups. The respondents were asked to register the extent to which they agree with statements on political leadership on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The index is divided by four, to give it the same scale range as the original items. The distribution on the items and the political leadership index, displayed in , reveals substantial variation in perceived political leadership.

Table 2. Dependent variables. Mean values and standard deviation.

Two comments about the dependent variable is in order. First, the councillors’ perception of own ability to perform the leadership task does not equal actual capacity for performing these tasks. However, perceived political leadership is an approximation of actual political leadership as councillors are likely to base their self-assessment on real-life experiences with performing the different leadership tasks. Councillors’ perception of own capacity for political leadership is also important because it is likely to motivate the politicians to continue their endeavours in the interest of the community. Second, as an anonymous reviewer made us aware of, role expectations may well interfere with the assessment of leadership behaviour. We cannot preclude the possibility that the respondents have had the normative expectations of what a councillor should do in mind, when assessing the statements about political leadership. This should be considered when interpreting the results.

The institutional designs are categorised in four groups according to the leadership type they support: executive, collective, distributive, or interactive. We have asked the administrative CEOs, and through them the secretaries for the city council, about whether the municipality has implemented 12 different designs (three designs in each category of political leadership). As indicated above, the different leadership designs are not mutually exclusive; for example, a municipality might simultaneously implement a design supporting collective leadership, a design supporting distributive leadership and two different designs supporting interactive leadership. A municipality can therefore implement from 0 to 12 designs.

The institutional designs are subsumed in four different additive indexes representing the four types of political leadership that they support. The leadership indexes range from 0 to 3 implemented designs within each category.

Whether the politician‒administrator relationship is balanced or not is measured on a 1‒10 scale, 1 indicating that the politicians have all the power, 10 that the municipal administration is all-powerful. Relationships scoring 4‒7 are regarded as balanced. The group identified as perceiving the relationship as imbalanced consequently includes both those who perceive the politicians as dominating (score 1‒3) and those who perceive the administration as dominating (8‒10). The distribution of all the independent variables applied in the analysis are displayed in . Control variables include individual characteristics likely to affect perceived political leadership: formal position (mayor or member of executive board), being from same party as the mayor, number of election periods, and gender. At the municipal level, we have controlled for municipal size since know from Dahl and Tufte (Citation1973) that municipal size may enhance effective governance, but limit citizens – something that recent research claims is dependent on institutional design (Goldsmith and Rose Citation2002). We have also controlled for municipal resources, based on the belief that resources are positively related to perceived political leadership. The resource measure is standardised between 1 and 10, relative to each country.

Table 3. Independent variables. Mean values and standard deviation.

As the political leadership index is at the ordinal level, we performed a single-level Ordered Probit Regression to assess the relationship between political leadership and different institutional designs.

The causal relationship between institutional designs and perceived political leadership is argued for theoretically. However, to empirically ascertain whether introducing certain institutional arrangements would produce a change in councillors’ perception of own ability to exercise political leadership, we would need data from before the designs were introduced. Our findings therefore have to be interpreted with caution and should be verified in future studies.

4. Results

The councillors were asked to assess how they performed in relation to three core functions of political leadership: the extent to which they contribute to agenda setting, solution design and generation of broad-based support. presents the descriptive statistics showing the percentage of councillors in Denmark and Norway who totally agreed that they succeeded in all these functions. As we see, Danish councillors feel significantly more confident of their ability to exercise political leadership than their Norwegian colleagues.

Table 4. Perceived political leadership. Councillors who agree that they contribute to the political agenda, to finding solutions and to mobilise support (per cent who agree).

In order to assess the potential effect of different types of institutional leadership designs on perceived political leadership, we mapped the prevalence of four types of institutional design. shows that all four design types – those intended to enhance executive leadership, collective leadership, interactive leadership and distributive leadership – were much more frequently reported in Danish than in Norwegian municipalities (see also Bentzen, Lo, and Winsvold 2019).

Table 5. Which type of institutional design is most frequently applied? Municipalities with different types of interactive institutions (per cent).

The preliminary analyses show that Danish politicians feel much more confident that they perform the basic political leadership functions and they are exposed to more of all four types of institutional leadership design. Do they feel more confident because of these arrangements? We investigate this question by assessing the contribution of different institutional leadership designs, controlled for other factors likely to impact on perceived political leadership: position, tenure, gender, municipal size and municipal resources. In a first model, we include the institutional designs only; in a second model, we include individual variables; and in a third and full model (Model 3a), we also include other variables at the municipal level as well as country. We also do separate analysis of those belonging to the mayor’s party and those who do not (Model 3b and 3c). displays the results of an ordered probit regression, where the local councillors’ ‘perceived political leadership’ is the dependent variable.

Table 6. Perceived political leadership. Ordered probit regression. Unstandardised coefficients.

Model 1 shows that three of the four types of institutional leadership designs are associated with an increase in perceived political leadership. Only interactive designs are associated with a decrease in perceived political leadership. The fact that executive and collective political leadership designs have a positive impact on perceived political leadership confirms our expectations. We had mixed expectations concerning the impact of the distributive and interactive designs. Here, the result suggests that the politicians’ positive evaluations of the delegation of decision-making power on less important matters to local citizens and their scepticism towards power-sharing in relation to more important policy issues gain the upper hand.

Model 2 includes the individual-level variables: election periods, position and gender. As expected, position (being mayor or on the executive board) and experience (election periods) have positive effects. There is also a negative effect of being female. Including these variables does not alter the effects of the different institutional designs. However, when we include the variable ‘country’ together with the municipal-level variables (Model 3a), the positive effect of three of the leadership arrangement indexes vanishes, and only the negative effect of interactive leadership design remains. Country (Danish councillors feel more empowered) and municipal size (councillors in large municipalities feel more empowered) seem to have an effect, and these variables have likely accounted for some of the variation ascribed to institutional design in the first two models. In other words, Danish councillors do not seem to feel more empowered than their Norwegian colleagues because Danish municipalities have implemented more designs to promote executive, collective and distributive political leadership, but rather because the Danish municipalities are larger, together with some other characteristics of the Danish polity or the Danish context that our data has been unable to account for.

Being mayor has, as expected, a significant and positive effect on perceived political leadership, as has belonging to the mayor’s party. When we split the sample between those who belong to the mayor’s party and the other councillors (Model 3b and 3c), an interesting pattern occur. Whereas the perceived political leadership of those not belonging to the mayor’s party appear to profit from distributive designs, the opposite is the case with those belonging to the mayor’s party. Distributive designs, in other words, might be a tool for political leadership among those without direct access to the mayor.

Interactive political leadership designs, however, have a significant negative effect on perceived political leadership across countries and across differently sized municipalities, and it also has a negative, albeit not significant effect across party affiliation (belonging to mayor’s party). As discussed in the theory section, we speculate that the impact of both distributive and interactive institutional designs on perceived political leadership may be contingent on whether elected councillors feel that there is a balanced power relationship between politicians and administrators in the municipality. Approximately half of the councillors regard this relationship as balanced (49%), whereas one-third see it as unbalanced in favour of the politicians, while 18% see this relationship as favouring the administration.

We assumed that a balanced power relation is likely to highlight the positive impact of the two participatory leadership designs on perceived political leadership, because the elected councillors feel that they have a considerable amount of political power that they can share with citizens and local stakeholders while, at the same time, they find that the administration is capable of facilitating the interaction and channel the new ideas into new policy solutions. By contrast, an imbalanced power relation will either render the politicians so disempowered that they will not want to share power with anybody or undermine the capacity of the administration to act as facilitator and arbiter.

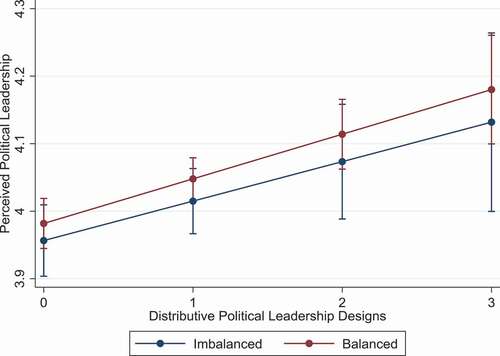

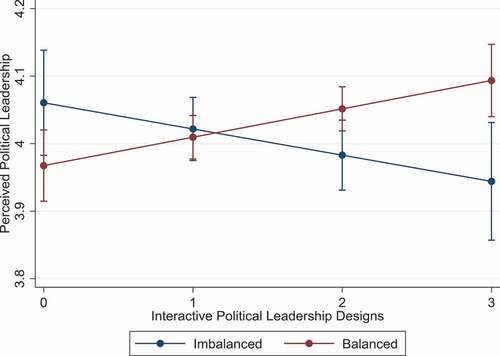

illustrate how the effect of the two participatory institutional leadership designs varies with the perceived politician‒administrator balance.

Figure 1. Distributive political leadership designs. Predicted values of perceived political leadership for those reporting balanced vs. imbalanced power relations between politicians and administrators.

Figure 2. Interactive political leadership designs. Predicted values of perceived political leadership for those reporting balanced vs. imbalanced power relations between politicians and administrators.

shows how the impact of distributive leadership designs is unaffected by the relative balance between politicians and administrators. By contrast, reveals a highly interesting result, namely that the impact of interactive political leadership designs on perceived political leadership is conditioned by the balance of the politician‒administrator relationship. Among the politicians who view this power relation as imbalanced (either in favour of themselves or the administrators), interactive leadership arrangements have a negative effect on perceived political leadership (declining regression line). Among the politicians who perceive the power relation as balanced, however, the effect of interactive arrangements is positive. displays the average marginal effect of interactive arrangements on perceived political leadership.

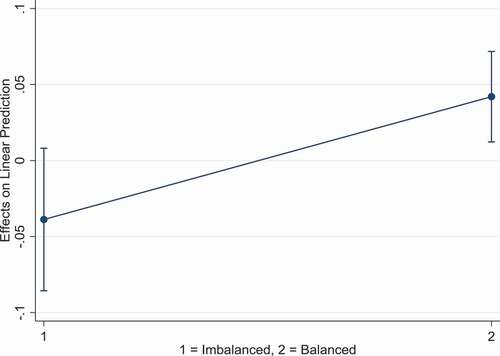

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of interactive political leadership designs on perceived political leadership.

shows us that among the politicians who perceive the power relation as imbalanced, interactive leadership designs have a negative effect, albeit one that is not statistically significant at a 95% level (the confidence intervals crosses the 0-line). Among the politicians perceiving the power relation as balanced, the effect of interactive arrangements is positive, and the effect is significant (the confidence interval does not cross the 0-line). The effects of interactive arrangements with the imbalanced and the balanced are significantly different from each other (the confidence intervals do not overlap).

5. Discussion

Although democratic theory emphasises the free and equal right of citizens to influence public decisions that affect their lives, political leadership is necessary to ensure effective governance (Kane, Patapan, and ’T Hart Citation2009). Democracy is not merely about ensuring broad-based input into the political system, but also about the production of legislative outputs capable of driving change. Political leaders play a key role in output production by setting the political agenda, designing solutions to problems that call for collective action, and mustering support for their implementation. The increasingly active, critical and competent followers of political leaders may provide valuable input to the problem diagnosis and design of solutions, and they are capable of evaluating the performance of the political leaders in regular elections (Nye Citation2008; Lees-Marshment Citation2015).

As discussed above, political leadership is under pressure, not least in the local municipalities where recreational politicians are expected to solve an increasing number of societal problems and public tasks and are scorned by local media if they fail to do so. National parliaments worldwide are launching institutional reforms aiming to enhance political leadership (Beetham Citation2006), as are many local municipalities (Berg and Rao Citation2005; Bentzen, Lo, and Winsvold 2019). Our analysis shows that local municipalities use a variety of institutional designs to support different forms of political leadership. Some of these institutional leadership designs seem to have a statistically significant positive effect on perceived leadership (when we control for individual and institutional factors). Hence, reforms intended to support sovereign, collective and distributive political leaderships appear to support local councillors in better performing their basic political leadership functions. The effects are relatively small, thus confirming the long causal chain connecting institutional reforms with political leadership practices and how they are perceived. Nevertheless, the lesson to draw from this analysis is that municipalities aiming to enhance democratic political leadership may benefit from tinkering with the design of the local political institutions.

We were curious regarding the impact of distributive and interactive institutional designs, and we are slightly surprised by the seemingly negative impact of interactive leadership designs on perceived political leadership, as we expected that the politicians’ problem diagnosis, solution design and implementation support would benefit from interaction with citizens and local stakeholders with other perspectives, forms of knowledge and ideas. To explain this finding, we examined the conditional effect of a politician‒administrator power balance and discovered an interaction effect revealing a positive impact of interactive leadership designs on perceived political leadership for politicians who see a balanced politician‒administrator relationship and a negative impact if there is an imbalance. Intuitively, this result makes good sense, since sharing power with local citizens and stakeholders in new forms of co-created policymaking will tend to appeal little both to disempowered politicians who think that the administration has the upper hand in policymaking and to strong and empowered politicians who think that they have the upper hand vis-à-vis the administration but doubt that the administration will be able to facilitate citizen participation in policymaking.

Although Denmark and Norway are similar in many respects, there are important differences when it comes to the political-administrative organisation. The larger Danish municipalities also mean that there are more resourceful and specialised administrations. Moreover, the hour-glass model in Norway means that the administrator‒politician collaboration is much narrower and less developed than in Denmark, where a more pragmatic approach has fostered traditions for more and less formalised collaboration across the politico-administrative domains. Despite these differences, however, the results of this study show the same pattern across both countries: A balanced power relationship between the political and administrative arena is key to making interactive designs contribute to how elected politicians exercise their political leadership functions.

Our study contributes to the further development of theories of democratic political leadership and institutional design. Institutional design is often discussed in relation to questions of how to enhance citizen participation in public governance (Smith Citation2009) rather than as a tool for strengthening political leadership (Sørensen and Torfing 2018). Similarly, political leadership is seldom discussed in relation to the institutional conditions for its exercise. Our analysis demonstrates that local municipalities are currently busy changing the institutional designs that determine the working conditions for elected councillors and that – under certain conditions – the different institutional designs may help enhance how local councillors perceive of political leadership performance.

Our study reveals that the power imbalance between politicians and administrators may prevent the former from reaping the fruits of interactive political leadership designs. The practical implication of this may be to explore further which factors impact the politician‒administrator relationship and how this power relation can become more balanced. Although the role of administrators in interactive governance has received some scholarly attention (Sørensen and Bentzen 2019), our knowledge about the challenges for administrators involved in interactive policy processes remains limited. Despite recent contributions (Sørensen and Torfing 2018, 2019b), the question of how interactive governance impacts the role of politicians and their interplay with the administration requires further investigation.

6. Conclusion

The conclusion is that institutional reforms aiming to change the designs that condition how local councillors exercise political leadership can indeed enhance their leadership. Different institutional designs may support and enhance different types of political leadership, but our empirical studies show that they all tend to have a positive association with how local councillors perceive of their political leadership role, as measured by the core political leadership functions set out in the literature. The positive association of interactive political leadership designs with perceived political leadership is, however, conditional upon the presence of a balanced power relation between politicians and administrators. Hence, the use of interactive institutional designs in the context of unbalanced politico‒administrative relations has a negative association with the local politicians’ perceptions of their respective contributions to diagnosing problems, designing solutions and mobilising support. This might not be surprising given that politicians who are battling the administration for power may see the introduction of new forms of power-sharing with citizens and stakeholders as threatening their political power rather than a welcome opportunity to further qualify their political leadership.

Our study sheds new light on the relationship between institutional design and political leadership, which tends to suffer from scholarly neglect. Our conclusions require further support, however, not least because we use ‘perceived political leadership’ as a proxy for the actual ability of elected councillors to exercise a democratic political leadership that can help convince local citizens that they are listened to and that pressing problems are dealt with in an efficient and legitimate manner.

To help local government officials seeking to enhance a particular type of political leadership, it would be helpful if further research in this field could develop a more fine-grained typology of practical institutional design changes and the forms of political leadership that they may support. Ideally, such a typology could guide local government reforms aiming to boost democratic political leadership. Additional empirical studies may be helpful towards understanding the impact of institutional designs on political leadership performance at other levels of government and in other countries. Mapping the conditions for successfully introducing and benefitting from interactive political leadership designs will serve to further test the interaction effect that we discovered in our study and identify other factors supporting co-created policymaking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jacob Torfing

Jacob Torfing is a professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Business of Roskilde University, Denmark, Director of the Roskilde School of Governance, and a professor at Nord University, Norway. His research interests include public sector reforms, political leadership, collaborative innovation and co-creation. He has published several books and scores of articles on these topics.

Tina Øllgaard Bentzen

Tina Øllgaard Bentzen is an associate professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Business of Roskilde University, Denmark. Her research focuses on participatory processes in the public sector and involves political leadership in municipalities, co-creation, administrative burdens and trust dynamics within governance.

Marte Slagsvold Winsvold

Marte Slagsvold Winsvold is a research fellow in the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo, Norway and the Norwegian Institute for Social Research. Her research interests include political representation, political leadership and political participation. She has published several articles and book chapters on these topics.

Notes

1. In traditional Weberian and Wilsonian thinking politics is above administration, but in reality, the relative influence between the political and the administrative level varies. In mayor-led municipalities the formal hierarchy between politics and administration is reinforced, whereas in manager-led municipalities the administrative level can be very powerful.

References

- Alexander, E. 2005. “Institutional Transformation and Planning: From Institutionalization Theory to Institutional Design.” Planning Theory 4 (3): 209‒223. doi:10.1177/1473095205058494.

- Bäck, H. 2005. “The Institutional Setting of Local Political Leadership and Community Involvement.” In Urban Governance and Democracy, edited by M. Haus, H. Heinelt, and M. Stewart, 75‒111. London: Routledge.

- Baiocchi, G. 2001. “Participation, Activism, and Politics: The Porto Alegre Experiment and Deliberative Democratic Theory.” Politics & Society 29 (1): 43‒72. doi:10.1177/0032329201029001003.

- Barber, M. 2007. Instruction to Deliver: Tony Blair, Public Services and the Challenge of Achieving Targets. London: Politico’s Publishing.

- Beetham, D., ed. 2006. Parliament and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Good Practice. Tielt: Lannoo.

- Berg, R., and N. Rao. 2005. Transforming Political Leadership in Local Government. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burns, J. 2004. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. New York: Grove Press.

- Chambers, S. 2006. Mayors and Schools: Minority Voices and Democratic Tensions in Urban Education. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Christensen, J., P. Christiansen, and M. Ibsen. 2011. Politik Og Forvaltning. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzel.

- Dahl, R., and E. Tufte. 1973. Size and Democracy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Dalton, R., and C. Welzel, eds. 2014. The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Edelman Inc. 2017. Edelman Trust Barometer 2017.

- Elcock, H. 2001. “A Surfeit of Strategies? Governing and Governance in the North-East of England.” Public Policy and Administration 16 (1): 59‒74. doi:10.1177/095207670101600104.

- Elgie, R. 2014. “The Institutional Approach to Political Leadership.” In Good Democratic Leadership, edited by J. Kane and H. Patapan, 139‒157. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Esaiasson, P. 2011. “Electoral Losers Revisited: How Citizens React to Defeat at the Ballot Box.” Electoral Studies 30 (1): 102‒113. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.009.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219‒245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Fung, A. 2003. “Survey Article: Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and Their Consequences.” Journal of Political Philosophy 11 (3): 338‒367. doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00181.

- Fung, A., and E. Wright. 2003. Deepening Democracy. London: Verso Press.

- Gissendanner, S. 2004. “Mayors, Governance Coalitions, and Strategic Capacity.” Urban Affairs Review 40 (1): 44‒77. doi:10.1177/1078087404267188.

- Goldsmith, M., and L. Rose. 2002. “Size and Democracy.” Environment and Planning C. Government and Policy 20 (6): 791–792. doi:10.1068/c2006ed.

- Goodin, R. 1998. The Theory of Institutional Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Greasley, S., and G. Stoker. 2008. “Mayors and Urban Governance.” Public Administration Review 78 (4): 722‒730.

- Greve, C., L. Rykkja, and P. Lægreid. 2016. Nordic Administrative Reforms. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grönlund, K., A. Bächtiger, and M. Setälä, eds. 2014. Deliberative Mini-Publics: Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process. Colchester: The ECPR Press.

- Gronn, P. 2002. “Distributed Leadership as a Unit of Analysis.” The Leadership Quarterly 13 (4): 423‒451. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00120-0.

- Haus, M., and D. Sweeting. 2006. “Local Democracy and Political Leadership: Drawing a Map.” Political Studies 54 (2): 267‒288. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00605.x.

- Helms, L. 2012. “The Importance of Studying Political Leadership Comparatively.” In Comparative Political Leadership, edited by L. Helms, 1‒24. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hendriks, C. 2016. “Coupling Citizens and Elites in Deliberative Systems: The Role of Institutional Design.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (1): 43‒60. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12123.

- Hendriks, F., and N. Karsten. 2014. “Theory of Democratic Leadership in Action.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership, edited by R. A. W. Rhodes and P. ’T Hart, 41‒56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hertting, N., and C. Kugelberg. 2017. “Representative Democracy and the Problem of Institutionalizing Local Participatory Governance. In Local Participatory Governance and Representative Democracy, 1‒17. London: Routledge.

- Invernizzi-Accetti, C., and F. Wolkenstein. 2017. “The Crisis of Party Democracy, Cognitive Mobilization, and the Case for Making Parties More Deliberative.” American Political Science Review 111 (1): 97‒109. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000526.

- Jun, K. 2007. “Event History Analysis of the Formation of Los Angeles Neighbourhood Councils.” Urban Affairs Review 43 (1): 107‒122. doi:10.1177/1078087407302123.

- Kane, J., H. Patapan, and P. ’T Hart. 2009. “Dispersed Democratic Leadership.” In Dispersed Democratic Leadership, edited by J. Kane, H. Patapan, and P. ’T Hart, 1‒12. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karsten, N., and F. Hendriks. 2017. “Don’t Call Me a Leader, but I Am One.” Leadership 13 (2): 154‒172. doi:10.1177/1742715016651711.

- Kellerman, B. 2015. Hard Times: Leadership in America. Stanford: Stanford Business Books.

- Kjær, U., and N. Opstrup. 2016. Variationer I Udvalgsstyret: Den Politiske Organisering I Syv Kommuner. Copenhagen: Kommuneforlaget.

- Koppenjan, J., M. Kars, and H. van der Voort. 2011. “Politicians as Metagovernors.” In Interactive Policy Making, Metagovernance and Democracy, edited by J. Torfing and P. Triantafillou, 129‒148. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Kotter, J., and P. Lawrence. 1974. Mayors in Action: Five Approaches to Urban Governance. New York: John Wiley.

- Ladner, A., N. Keuffer, and H. Baldersheim. 2016. “Measuring Local Autonomy in 39 Countries (1990–2014).” Regional and Federal Studies 26 (3): 321‒357. doi:10.1080/13597566.2016.1214911.

- Leach, S., and D. Wilson. 2002. “Rethinking Local Political Leadership.” Public Administration 80 (4): 665‒689. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00323.

- Lees-Marshment, J. 2015. The Ministry of Public Input: Integrating Citizen Views into Political Leadership. New York: Springer.

- March, J. G., and J. P. Olsen. 1995. Democratic Governance. New York: The Free Press.

- Masciulli, J., M. Molchanov, and W. Knight. 2009. “Political Leadership in Context.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Political Leadership, edited by J. Masciulli, M. Molchanov, and W. Knight, 3‒30. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Mikalsen, K., and H. Bjørnå. 2015. “Den Norske Ordføreren: Begrenset Myndighet, Mye Makt?” In Lokalpolitisk Lederskap I Norden, edited by N. Aarsæther and K. Mikalsen, 169‒195. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Morrell, K., and J. Hartley. 2006. “A Model of Political Leadership.” Human Relations 59 (4): 483‒504. doi:10.1177/0018726706065371.

- Mouritzen, P., and J. Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators of Western Local Governments. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press.

- Neblo, M., K. Esterling, and D. Lazer. 2018. Politics with the People: Building a Directly Representative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Newton, K., and B. Geissel, eds. 2012. Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise? London: Routledge.

- Nye, J. 2008. The Powers to Lead. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, B. G. 2012. Institutional Theory in Political Science, the New Institutionalism. 3rd ed. New York: Continuum.

- Peters, B. G., and J. Pierre, eds. 2004. The Politicization of the Civil Service in Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Reuchamps, M., and J. Suiter, eds. 2016. Constitutional Deliberative Democracy in Europe. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Rose, L., and K. Ståhlberg. 2005. “The Nordic Countries: Still the ‘Promised Land?’.” In Local Governance, edited by B. Denters and L. Rose., 83‒99. Basingstroke: Houndsmills, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sletnes, I. 2015. “Ordførerrollen I Norden I Et Rettslig Perspektiv.” In Lokalpolitisk Lederskap I Norden, edited by N. Aarsæther and K. Mikalsen, 28‒68. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Smith, G. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sørensen, E. 2006. “Metagovernance: The Changing Role of Politicians in Processes of Democratic Governance.” The American Review of Public Administration 36 (1): 98‒114. doi:10.1177/0275074005282584.

- Sørensen, E. 2020. Interactive Political Leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stoker, G. 2016. Why Politics Matters. London: Macmillan.

- Stoker, G., and C. Hay. 2017. “Understanding and Challenging Populist Negativity Towards Politics: The Perspectives of British Citizens.” Political Studies 65 (1): 4‒23. doi:10.1177/0032321715607511.

- Svara, J. 1990. Official Leadership in the City, Patterns of Conflict and Cooperation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Svara, J. 1994. “The Structural Reform Impulse in Local Government.” National Civic Review 83 (3): 323–347. doi:10.1002/ncr.4100830312.

- Svara, J. 2001. “The Myth of the Dichotomy: Complementarity of Politics and Administration in the past and Future of Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 61 (2): 176‒183. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00020.

- Tucker, R. C. 1995. Politics as Leadership. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

- Uhl-Bien, M., and M. Carsten. 2016. “Followership in Context.” In The Routledge Companion to Leadership, edited by J. Storey, et al., 142–168. London: Routledge.

- Vabo, S. 2000. “New Organisational Solutions in Norwegian Local Councils.” Scandinavian Political Studies 23 (4): 343‒372. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00041.