ABSTRACT

Governments do not exclusively buy from the cheapest bidder and increasingly use public procurement as a policy instrument to achieve wider environmental, innovative and social objectives. Past studies have shown the process of government contracting to be connected to political factors. This paper studies the extent to which politicians’ preferences for price and non-price criteria in the contract awarding stage are associated with politicians’ ideological reasoning (the Citizen Candidate model), and strategic reasoning (the Downsian approach). Politicians’ preferences are analysed through a discrete choice experiment. We find that politicians’ preferences for non-price criteria are strongly connected to ideological reasoning and to a limited extent to strategic reasoning. We also observe that, regardless of their political ideology and financial situation of the municipality, politicians are willing to look beyond price, and consider environmental, innovative and social criteria when awarding contracts.

Introduction

Public procurement represents approximately 14% of the gross domestic product of the European single market every year (European Commission Citation2019) and has therefore often been identified as ‘the largest business sector in the world’ (Grandia Citation2016, 183). In line with neo-classical contracting theory, the process of government contracting has long been associated with government efficiency and cost reduction objectives (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). The primary goal of government contracting was to decrease the costs connected to the delivery of public services through the introduction of competition (Ferris and Graddy Citation1986; Ferris Citation1986), leading governments to almost exclusively award contracts based on price (Keulemans and Van de Walle Citation2017).

Yet, although price remains an essential criterion (Igarashi, De Boer, and Michelsen Citation2015; Young, Nagpal, and Adams Citation2016; Fuentes-Bargues, González-Cruz, and González-Fuentes-Bargues et al. Citation2017), governments are increasingly willing to link public procurement contracts to the realisation of secondary policy goals such as environmental, social, and innovation-related objectives (Morettini Citation2011; McCrudden Citation2004; Walker and Brammer Citation2009; Uyarra et al. Citation2014; Aldenius and Khan Citation2017). Public procurement has consequently developed over the years as a policy instrument to promote a multitude of policy goals that are difficult to attain otherwise, such as environmentally friendly policies, social justice, good governance, and public sector innovation. Thanks to the inclusion of secondary policy objectives in public procurement contracts, governments are capable of creating value for society (Mouraviev and Kakabadse Citation2015), and regulating the market (Jaehrling Citation2015).

Bel and Fageda (Citation2017) argue that the process of government contracting is closely connected to political characteristics, and, more particularly to ideological attitudes, and political interests. This strand of the contracting out literature exclusively focuses on governments’ decision to insource or outsource the delivery of public services. Yet, little attention has been paid to how contract awarding may be associated with political characteristics. Once the decision to outsource a public service has been taken, governments have to evaluate the offers based on various criteria (e.g., price, environmental, innovative, and social aspects) and are supposed to award the contract to the best candidate. Similar to the decision to insource or outsource a public service, some governments might be more willing to promote certain criteria over others depending on political interests, and politicians’ political ideology. This research therefore intends to study the extent to which politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives in the contract awarding stage are associated with politicians’ political ideology and political interests.

Among the limited studies examining the relationship between secondary policy objectives and political characteristics, several empirical studies in the US found that local entities that are predominantly liberal are more likely than republican ones to opt for sustainable practices such as the inclusion of environmental and social criteria into government contracts (Konisky, Milyo, and Richardson Citation2008; Portney and Berry Citation2010; Wang et al. Citation2012; Opp and Saunders Citation2012; Alkadry, Trammell, and Dimand Citation2019). Opp and Saunders (Citation2012, 688) explain that ‘Republicans are less likely to trust government and embrace government solutions to perceived societal problems compared with Democrats’. In contrast, Lubell, Feiock, and Handy (Citation2009) highlight that the political context plays a minor role in the development of sustainable practices at the municipal level.

These studies however suffer from a number of limitations that our research aims at addressing. First, Alkadry, Trammell, and Dimand (Citation2019) highlight the importance of political characteristics in sustainable procurement. However, in contrast with our research, previous studies rarely distinguish between political interests and decision-makers’ political ideology. Second, few empirical studies have analysed decision-makers’ attitudes in public procurement (Trammell, Abutabenjeh, and Dimand Citation2019), and if they do, they do not examine the environmental, innovative and social criteria simultaneously. Given this gap, our research aims at developing a more comprehensive understanding of politicians’ preferences for the full range of secondary policy objectives (environmental, innovative, and social features). Lastly, Bel and Fageda (Citation2009) found that the influence of ideological attitudes on service delivery practices highly depends on the geographical area. Because most empirical studies examining the association between political characteristics and secondary policy objectives were conducted in the US (Konisky, Milyo, and Richardson Citation2008; Portney and Berry Citation2010; Wang et al. Citation2012; Opp and Saunders Citation2012; Alkadry, Trammell, and Dimand Citation2019; Lubell, Feiock, and Handy Citation2009), it is difficult to generalise their findings to other contexts. By examining a European country, our study aims at investigating this phenomenon in another geographical context.

To fill these gaps, this study empirically examines the extent to which politicians’ consideration of price and secondary policy objectives may be associated with the political context. We consider that a political context is constituted of two different dimensions: politicians’ political ideology (the Citizen Candidate model), and political interests (the Downsian approach). We argue that each dimension can be related to politicians’ consideration of price and secondary policy objectives. Whereas the Citizen Candidate model predicts that politicians’ public policy choices are driven by their political ideology (Osborne and Slivinski Citation1996; Elinder and Jordahl Citation2013; Alonso, Andrews, and Hodgkinson Citation2016), the Downsian model postulates that politicians’ public policy preferences are determined by the preferences of the median voter, and are consequently the result of some strategic reasoning (Downs Citation1957; Elinder and Jordahl Citation2013; Alonso, Andrews, and Hodgkinson Citation2016). Politicians’ preferences are derived from a discrete choice experiment which focuses on the awarding of contracts to for-profit enterprises in the field of waste collection at the municipal level in Belgium.

This article is structured as follows. The first section outlines the theoretical background as well as the hypotheses that will be tested in this study. The second section describes the research setting, the design of the discrete choice experiment, the data collection, the operationalisation of the relevant variables, the sample, and the empirical strategy. The penultimate section presents, and discusses the empirical findings. The final section highlights the implications of our results, the limitations, and the avenues for future research.

Politicians’ Ideological and Strategic Reasoning

Citizen candidate model – ideological reasoning

The Citizen Candidate model has been developed to examine electoral participation, and the factors influencing individuals’ decision to run for office in a representative democracy (Osborne and Slivinski Citation1996). According to this approach, citizens’ motivations to become candidates are driven by the perspective of being able to formulate and implement their preferred public policies (Osborne and Slivinski Citation1996; Elinder and Jordahl Citation2013; Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018). Once elected, officeholders will aspire to carry out their policy objectives, taking into account the constraints that are inherent to their position (Osborne and Slivinski Citation1996). From this perspective, it can be expected that different ideological preferences will also imply different formulation and implementation of public policies (Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018). According to Elinder and Jordahl (Citation2013), the Citizen Candidate model can explain the divergence in public policy choices between right-wing and left-wing politicians.

In line with the Citizen Candidate approach, we claim that politicians choose their preferred level of price, environmental, innovative and social standards according to their political ideology. We argue that right-wing and left-wing politicians’ divergent preferences with regards to price and secondary policy objectives mainly reside in right-wing and left-wing politicians’ different ideological opinions on the role of the state. While left-wing politicians strongly favour state-oriented solutions, right-wing politicians prefer to rely on market-oriented solutions (Guo and Willner Citation2017). The ideological positions are also very different when it comes to public spending. The literature highlights that, compared to left-wing politicians, right-wing politicians pay more attention at diminishing public expenditures (Bel and Fageda Citation2009; Petersen, Houlberg, and Christensen Citation2015). Furthermore, Serritzlew (Citation2003, 332) states that ‘[l]eft-wing government leads to increased public spending’.

In light of these observations and the high-cost secondary policy objectives can generate (Walker and Brammer Citation2009), we expect that right-wing politicians consider that the government should not subsidise the development of secondary policy objectives. In contrast, we predict that left-wing politicians consider that developing secondary policy objectives should be the role of the state. Therefore, we assume that right-wing politicians will be more hesitant than left-wing politicians to consider environmental, innovative and social criteria. Yet, as very limited attention has been paid to the association between politicians’ preferences for secondary policy objectives and political ideology, the formulation of the hypotheses remains relatively exploratory. Based on the previous argument, we develop the following hypotheses:

H1a: Compared to left-wing politicians, right-wing politicians are more likely to consider price when awarding contracts.

H1b: Compared to left-wing politicians, right-wing politicians are less likely to consider environmental criteria when awarding contracts.

H1c: Compared to left-wing politicians, right-wing politicians are less likely to consider innovation-related criteria when awarding contracts.

H1d: Compared to left-wing politicians, right-wing politicians are less likely to consider social criteria when awarding contracts.

Downsian approach – strategic reasoning

Taking an economic perspective, the Downsian approach considers that politicians can be viewed as actors who perform their social function of formulating, and carrying out public policies with the unique aim of gaining political support from their constituents (Downs Citation1957). The theory postulates that, to attract political support and to gain an executive position, politicians attach great importance to develop public policy proposals that are favourable to the median voter (Elinder and Jordahl Citation2013; Alonso, Andrews, and Hodgkinson Citation2016; Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018). From this perspective, voters’ political interests guide politicians’ formulation, and implementation of public policies; ‘when most members of the electorate know what policies best serve their interests, the government is forced to follow those policies in order to avoid defeat’ (Downs Citation1957, 147). Politicians’ public policy choices therefore depend on the preferences of the median voter rather than their own ideological preferences (Elinder and Jordahl Citation2013).

Consistent with the Downsian approach, we highlight that, in order to gain electoral support, politicians tend to rely on the preferences of the median voter with respect to the implementation of secondary policy objectives. In line with Downs (Citation1957), we claim that voters’ income is a crucial mechanism behind politicians’ consideration of secondary policy objectives.

According to Wang, Hawkins, and Berman (Citation2014, 9), ‘high income populations may be more willing to participate and render resources because they perceive a high stake in sustainability policies’, implying that richer communities are more likely to support the development of secondary policy objectives. In line with this argument, Alkadry, Trammell, and Dimand (Citation2019) found that municipalities with higher income population were more likely to consider sustainable practices. Therefore, politicians in higher-income municipalities might be more inclined to take secondary policy objectives into consideration, as this appears to be more in line with voters’ desires.

In municipalities with lower-income residents, taking secondary policy objectives into consideration might be perceived as an unnecessary measure by the constituents who might feel their financial interests threatened (Fernandez, Ryu, and Brudney Citation2008). One could argue that, in municipalities where voters have fewer means, residents are also more dependent on social benefits received from local governments. Individuals with lower incomes might therefore be afraid that higher spending on the secondary policy objectives increases the overall deficit of their municipality, potentially jeopardising the benefits they receive from their local entity (Fernandez, Ryu, and Brudney Citation2008). Therefore, we assume that in municipalities with lower-income voters, politicians tend not to take secondary policy objectives into consideration as these are not favoured by their constituents. Yet, in contrast with the innovative and environmental criteria, taking the social criterion into consideration might be perceived as a favourable policy decision to boost employment and social justice. Voters in lower-income municipalities might consequently be supportive of this type of measure, giving some impetus to the politicians to consider this criterion.

As few studies have examined the relationship between politicians’ preferences for secondary policy objectives, and voters’ political interests, this research remains exploratory in the formulation of its hypotheses. Based on the aforementioned observations, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H2a: In municipalities with lower-income residents, politicians will be more likely to consider price when awarding contracts.

H2b: In municipalities with lower-income residents, politicians will be less likely to consider environmental criteria when awarding contracts.

H2c: In municipalities with lower-income residents, politicians will be less likely to consider innovation-related criteria when awarding contracts.

H2d: In municipalities with lower-income residents, politicians will be more likely to consider social criteria when awarding contracts.

Data and Method

We conduct a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to examine the extent to which politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives are connected to politicians’ political ideology and political interests. In a DCE, participants are given a hypothetical scenario and have to select, across several choice sets, the option they favour the most. They are presented with at least two options per choice set and each option is described by a set of attributes that can take several levels (Lancsar and Louviere Citation2008; Lancsar, Fiebig, and Hole Citation2017).

Research setting

We examine politicians’ preferences for price, and secondary policy objectives in the field of waste collection at the local level in Belgium. We focus on government contracting to for-profit enterprises as they are the most frequent external service provider selected by local decision-makers to deliver public services (Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018). We chose the waste collection sector as it is considered one of the most visible and essential public service provided by local authorities to the population. In addition, Schoute, Budding, and Gradus (Citation2018) observed that waste collection services are mostly contracted out to for-profit enterprises. We concentrate on the door-to-door collection of bulky waste, which is a particular type of municipal waste that is too big to be placed in standard waste containers. It includes items such as old furniture, mattresses or white goods.

Design of the discrete choice experiment

During the DCE, politicians were given a hypothetical scenario that the municipality, where they occupy a decision-making position, has decided to award a new contract for the collection of bulky waste. The scenario then asks politicians to choose among two for-profit enterprises described by price and environmental, innovative and social criteria the one that should become, in their opinion, the new bulky waste collector of their municipality. Additionally, in order to deal with potential endogeneity issues resulting from omitted attributes, we instructed participants to exclusively rely on the attributes given in the DCE (Lancsar and Louviere Citation2008). Although we do not rule out the risk that some participants may have disregarded this instruction, we argue, in line with Lancsar and Louviere (Citation2008), that this substantially reduces the risk of omitted variable bias.

Operationalisation of the criteria

This study focuses on four criteria: price, environmental, innovative, and social criteria. These three secondary policy objectives have been selected as the European Commission has concentrated on their integration into government contracts. Moreover, Belgium has developed strategies to encourage their inclusion into public procurement contracts (OECD Citation2019). By including secondary policy objectives into public procurement contracts, governments aim at developing environmentally friendly solutions (Testa et al. Citation2012), promoting social benefits for society (Loosemore Citation2016), and stimulating the creation of innovative goods and services (Uyarra et al. Citation2014).

Price, environmental, innovative, and social criteria were operationalised in a three-step procedure. First, we conducted a desk research of the documents concerning the implementation of environmental, innovative, and social criteria, of the main waste collection companies operating in Belgium. From these strategic plans, we were able to derive a first list of attributes.

Second, we conducted six face-to-face semi-structured interviews with experts in the waste collection field in Belgium. The interviewees were selected purposively based on their expertise and experience in waste collection, and came from different management levels, including waste collection agencies, inter-municipal associations, a bulky waste collection enterprise and a municipality. Each interview lasted approximately 1 hour and was divided into two parts. In the first part of the interview, questions about the organisation and the contracting out process of waste collection at the municipal level were asked to the experts. The second part of the interview focused on the secondary policy objectives. Based on the list of attributes derived from the desk research, experts were asked to rank the attributes from the most important to the least important one. They could also add attributes to the list if they consider a non-price criteria could be better operationalised by another attribute. As a result of the interviews, four attributes and their respective levels were identified as being the most considered by the experts (see ). The four attributes were chosen by the experts to reflect as closely as possible the reality of the bulky waste collection market.

Table 1. Attributes and their respective levels.

As a last step, and to check the reliability and validity of these most considered attributes, we conducted a pilot study of the DCE with civil servants dealing with waste collection at the municipal level. During the pilot study, we asked participants to describe orally how they understood the attributes and they did not observe any inconsistencies.

Fractional factorial design

Because the total number of choice sets to show to the respondents is quite large, we conducted a fractional factorial design to decrease it. It is defined as ‘a sample from the full factorial selected such that all effects of interest can be estimated’ (Lancsar & Louviere, Citation2008, 667). To ensure orthogonality (the statistical independence of the attributes) and level balance (all the attribute levels have the same likelihood to appear throughout the choice sets), we performed the rotation method in R using an orthogonal main effect array (Ryan et al. Citation2012; Aizaki Citation2012). The number of possible choice sets was reduced to 12 and divided into two blocks of 6 choice sets (see in the appendix for an example of a choice set). Respondents were then randomly assigned to one of the two blocks and had to assess six choice sets consisting of two alternatives each.

Data collection

As, in Belgium, waste collection falls under the umbrella of the environmental department of the municipality, we surveyed the executive politicians (aldermen or mayors) responsible for the environmental portfolio of their municipality. These politicians therefore have direct experience with the selection of waste collectors, implying that they can easily recognise how environmental, innovative and social criteria were operationalised in the DCE. Moreover, in our sample, most of the politicians stated to have already evaluated tender documents, confirming that the local politicians surveyed are experienced with regards to contract awarding.

The survey-experiment was sent to all the Belgian local politicians we identified as responsible for the environmental portfolio of their municipalities (556 politicians). Their contact details were collected via a database collecting information on Belgian administrations. When the contact details were not available in the database, we manually searched for them on the website of the municipality. The DCE was translated into Dutch and French, the two main official languages of Belgium, and was electronically distributed via personalised emails to the politicians.

Measure of political ideology and political interests

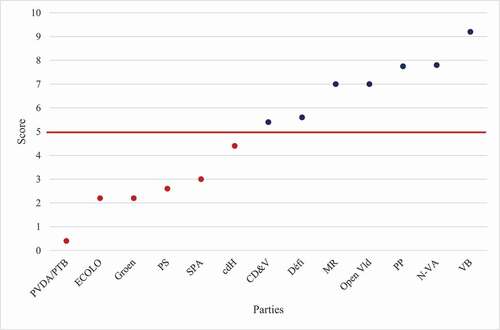

Similar to previous government contracting studies (Bhatti, Olsen, and Pedersen Citation2009; Zafra-Gómez et al. Citation2016; Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018), we measured political ideology through politicians’ party affiliation. We manually searched for the respondents’ party affiliation on the website of their municipality. We used the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey to place the politicians into the left-wing or right-wing group (see in the appendix) (Polk et al. Citation2017). The Chapel Hill expert survey was previously used by Schoute, Budding, and Gradus (Citation2018) in their study on local governments’ decision to contract out.

Yet, many Belgian politicians are affiliated to a local party at the municipal level in Belgium and Otjes (Citation2018) states that local parties constitute a separate group that cannot be directly associated to a right-wing or left-wing ideology. It was therefore crucial to generate a categorical variable, including right-wing, left-wing and local parties to examine local politicians’ preferences. Having a continuous measure of ideology would have resulted in some important loss of data and empirical results as we would not have been able to include politicians from local parties.

In line with past research on political interests (Downs Citation1957; Fernandez, Ryu, and Brudney Citation2008; Sundell and Lapuente Citation2012), we operationalise political interests by the average income of the population. For this purpose, we examine the average income per inhabitant for every municipality. This variable has been divided into four categories according to the quartiles of the distribution; low, medium-low, medium-high and high average income municipalities per inhabitant.

Data description

The response rate is 31.7%, indicating that a total of 176 Belgian politicians responded to the DCE. To examine the reliability of those answers, we compare politicians’ stated gender (the one specified in the survey-experiment) with their actual gender. As two politicians stated a different gender than their actual gender, we considered their answers not reliable, and deleted them from the dataset. In addition, we took a closer look at the discrete choices of politicians who answered in less than 4 min (the estimated minimum time to complete the survey-experiment). After a close inspection of four politicians who were considered ‘too fast’, no answer was found to be problematic or irrational. A total of 174 respondents are therefore analysed.

We examine the representativeness of our sample by looking at variables at the level of the municipality (region, population size and average income per inhabitant) and the individual level (gender and function in the municipality). The sample appears to be representative of the population (see in the appendix). Most of the politicians in our sample are males, middle aged, aldermen, and have a university degree as well as experience with contract awarding (see in the appendix).

Empirical strategy

The dependent variable of this research is either 1 for the for-profit enterprise that is chosen or 0 for the for-profit enterprise that is not chosen by the politicians. Therefore, we conduct a conditional (fixed effects) logistic regression that has been shown by McFadden (Citation1974) to be in line with random utility theory. The level of the fixed effect has been specified at the choice set level (Ryan et al. Citation2012). As politicians’ party affiliation and average income per inhabitant remain constant over alternatives, they can only be included as interaction terms in the regression models (Train Citation2002). We therefore interact the secondary policy objectives with politicians’ party affiliation and average income per inhabitant to test our hypotheses. It is worth noting that this study interprets the interaction effects as multiplicative effects, via odds ratio, instead of an additive scale.

Empirical analysis

Ideological reasoning – findings

In line with government contracting studies that find a relationship between political ideology and the decision to contract out (Dubin and Navarro Citation1988; Bhatti, Olsen, and Pedersen Citation2009; Plantinga, de Ridder, and Corra Citation2011; Zafra-Gómez et al. Citation2016; Schoute, Budding, and Gradus Citation2018), we observe, except for price, that the divergent political ideologies of politicians lead to different levels of preferences for the secondary policy objectives (see ). Our study therefore confirms the existence of ideological reasoning when politicians consider secondary policy objectives. Yet, all politicians, independent of their ideology, are more likely to take lower prices, and higher environmental, innovative, and social criteria into consideration.

Table 2. Ideological reasoning – politicians’ preferences for the criteria.

With regards to price (see model 1), we could not find any significant difference between right-wing politicians and left-wing politicians. This finding contradicts previous government contracting studies observing that ideological attitudes predict government contracting decisions (Bel and Fageda Citation2009; Petersen, Houlberg, and Christensen Citation2015; Serritzlew Citation2003), as well as our assumption that right-wing politicians will be more likely than left-wing politicians to consider price.

Conclusions about the environmental aspect (see model 2 and 3) need to be treated with caution. On the one hand, in line with our hypothesis, the results show that, compared to right-wing politicians, left-wing politicians are 2.17 times more likely to award contracts to for-profit enterprises with an average age of the fleet of 3 years compared to for-profit enterprises with an average age of the fleet of 6 years. On the other hand, the output also indicates that left-wing politicians are less likely than right-wing politicians to award contracts to for-profit enterprises with a new fleet of vehicles compared to for-profit enterprises with an average age of the fleet of 6 years. We consequently cannot conclude whether left-wing or right-wing politicians have stronger preferences for the environmental criterion. Next, the coefficient of the interaction term between political ideology and the innovative criterion (see model 4) shows that, left-wing politicians are less likely than right-wing politicians to award contracts to for-profit enterprises with an app compared to for-profit enterprises that do not offer an app.

Although secondary policy objectives are often considered costly (Walker and Brammer Citation2009), right-wing politicians appear to consider for-profit enterprises with a new fleet of vehicles and a mobile application to a larger extent than left-wing politicians. In line with Dubin and Navarro (Citation1988) who highlighted that politicians might be willing to pay more for better ideologically aligned values, we advance the assumption that right-wing politicians might encourage the development of environmental and innovative practices to reflect their ideological preferences.

Alternatively, one could argue that right-wing politicians may still aim to reduce public expenditures by being more likely to choose, compared to left-wing politicians, for-profit enterprises with a new fleet of vehicles and a mobile application. Although innovative solutions may require some significant initial investments, one of their main objectives is to increase the efficiency of public services and, as a result, to reduce its costs. In addition, right-wing politicians may see a new fleet of vehicles as the sign that the for-profit enterprise is quite modern and innovative rather than environmentally friendly. Having a new fleet of vehicles may reduce the potential long-term costs associated with an older fleet of vehicles and might also be more efficient.

The interaction term between political ideology and the social criterion (see model 5) shows that left-wing politicians are 2.41 times more likely than right-wing politicians to award contracts to for-profit enterprises that have a training scheme for long-term unemployed compared to for-profit enterprises that do not have it, confirming H1d. This finding is in line with previous studies arguing that left-wing politicians promote pro-social values and pay great attention to the working conditions of the workers (Sørensen and Bay Citation2002; Lindh and Sevä Citation2018). Left-wing politicians appear to pursue their own political objectives by choosing to promote the social conditions of their municipality.

Finally, our findings shed light on the preferences of politicians affiliated to local parties in Belgium, and indicate that right-wing politicians’ preferences significantly differ from the ones of politicians affiliated to local parties for price, the new fleet of vehicles and the social criterion. Politicians affiliated to local parties, are 1.03 times more likely than right-wing politicians to take the highest price into consideration compared to the lowest price (see model 1). With regards to the environment, politicians affiliated to local parties are less likely than right-wing politicians to consider a new fleet of vehicles compared to a for-profit enterprise with an average age of the fleet of vehicles of 6 years (see model 3). Compared to right-wing politicians, politicians affiliated to local parties are 1.5 times more inclined to award contracts to for-profit enterprises currently involved in a training scheme for long-term unemployed (see model 5).

Strategic reasoning – findings

Our results, displayed in , show that only one result is found to be statistically significant. Compared to municipalities with a low average income per inhabitant, municipalities with a high average income per inhabitant are 1.95 times more likely to award contracts to for-profit enterprises with a new fleet of vehicles compared to for-profit enterprises with an average age of the fleet of 6 years, confirming H2b. Yet, except from this result, our research suggests that politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives do not appear to be linked to voters’ political interests. It worth noting that all politicians, independent of the financial situation of the municipality, are more likely to take lower prices, higher environmental, innovative, and social criteria into consideration.

Table 3. Strategic reasoning – politicians’ preferences for the criteria (average income/inhabitant).

Discussion and Conclusion

Previous studies have shown that the process of government contracting is influenced by political factors (Bel and Fageda). Yet, little empirical evidence exists on the relationship between political characteristics and the next stage of government contracting; the process of contract awarding where decision-makers evaluate tender documents based on numerous criteria such as environmental, innovative and social objectives. This research therefore aimed at investigating the extent to which politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives during the contract awarding stage are related to the political context. We understood the political context as being composed of two aspects: politicians’ political ideology (Citizen Candidate model), and political interests (the Downsian approach).

The findings indicated that, in addition to price, politicians are willing to consider environmental, innovative and social criteria when awarding contracts. We also found that politicians’ preferences for secondary policy objectives are associated with political ideology, supporting the Citizen Candidate model. However, limited support has been found for the Downsian approach with only one hypothesis (H2b) being supported.

Our study provides three main relevant implications for research on government contracting and public procurement. First, our analysis sheds light on politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives. A topic that has hitherto received very limited attention from past research. Our results suggest that, regardless of their political ideology, politicians are willing to consider environmental, innovative and social criteria when awarding contracts. This finding significantly contributes to the field of public procurement where limited studies examining politicians’ attitudes have been conducted (Trammell, Abutabenjeh, and Dimand Citation2019). Moreover, by simultaneously examining politicians’ preferences for environmental, innovative and social criteria, our study sheds light on politicians’ stated behaviour with regards to the full range of secondary policy objectives.

Next, our study shows that politicians seem to be guided by their political ideology and aim at implementing and carrying out their preferred policies. This finding contradicts previous government contracting studies that did not find any statistical relationships between political ideology and the decision to insource or outsource public services (Bel and Fageda Citation2017). This indicates that the political mechanisms associated with the contract awarding stage might be somehow different from the ones connected to the decision to contract out.

Few studies have conducted experimental research in the field of public procurement. More particularly, DCEs have rarely been carried out in public administration (but see Van Puyvelde et al. Citation2016; Jensen and Pedersen Citation2017; Bellé and Cantarelli Citation2018). We believe that DCEs constitute a reliable method to derive valid preferences for government contracting arrangements.

Despite these contributions, our research has some limitations that create avenues for future studies. First, we investigated the relationship between politicians’ preferences for price and secondary policy objectives and voters’ political interests in a technical service but one could argue that voters’ political interests might be more prominent in social services. The population might show more interest in influencing the outcome of contract awarding for social services as they might feel more directly concerned or might see it as one of the main prerogatives of the state. Future studies should examine whether our findings, especially with regards to political interests, are similar in social services. Additionally, future research should investigate other sets of secondary policy objectives that the ones identified in this study.

Second, the focus of our study on bulky waste collection in Belgium restrains the generalisability of our findings. Yet, the organisation of waste collection is quite similar across European countries. We, therefore, believe that our conclusions could be applicable to other countries in the European Union where secondary policy objectives are also taking a more prominent role. Future research should intend to confirm this expectation by examining this phenomenon in different contexts.

Finally, to be as close as possible to real-life decisions, this study exclusively surveyed politicians who are responsible for waste collection, and consequently the environmental department of their municipality – as waste collection falls under the umbrella of the environmental department. These politicians might consequently be more sensitive towards environmental issues than other politicians, resulting in higher preferences for the environmental criterion (Baekgaard Citation2010). However, we believe that it reflects a real-life setting where politicians responsible for the environment might also be more likely to favour green policies through public procurement contracts.

Online_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (28.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amandine Lerusse

Amandine Lerusse is a doctoral researcher and teaching assistant at the KU Leuven Public Governance Institute, Belgium. Her research examines, through an experimental approach, politicians’ and public managers’ decision-making behaviour and preferences with regard to external service providers.

Steven Van de Walle

Steven Van de Walle is a research professor of public management at the KU Leuven Public Governance Institute, Belgium. His research interests include public sector reform and interactions between citizens and public services. His work has been published in leading public administration journals, including Governance and Public Administration Review.

References

- Aizaki, H. 2012. “Basic Functions for Supporting an Implementation of Choice Experiment in R.” Journal of Statistical Software 50 (2): 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.196.

- Aldenius, M., and J. Khan. 2017. “Strategic Use of Green Public Procurement in the Bus Sector: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 164: 250–257. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.196.

- Alkadry, M. G., E. Trammell, and A. M. Dimand. 2019. “The Power of Public Procurement: Social Equity and Sustainability as Externalities and as Deliberate Policy Tools.” International Journal of Procurement Management 12 (3): 336–362. doi:10.1504/IJPM.2019.099553.

- Alonso, J. M., R. Andrews, and I. R. Hodgkinson. 2016. “Institutional, Ideological and Political Influences on Local Government Contracting: Evidence from England.” Public Administration 94 (1): 244–262. doi:10.1111/padm.12216.

- Baekgaard, M. 2010. “Self-Selection or Socialization? A Dynamic Analysis of Committee Member Preferences.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 35 (3): 337–359. doi:10.3162/036298010792069189.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2009. “Factors Explaining Local Privatization: A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Public Choice 139 (1–2): 105–119. doi:10.1007/s11127-008-9381-z.

- Bel, Germà, and Xavier Fageda. 2017. “What Have We Learned from the Last Three Decades of Empirical Studies on Factors Driving Local Privatisation?” Local Government Studies 43 (4): 503–11

- Bellé, N., and P. Cantarelli. 2018. “The Role of Motivation and Leadership in Public Employees’ Job Preferences: Evidence from Two Discrete Choice Experiments.” International Public Management Journal 21 (2): 191–212. doi:10.1080/10967494.2018.1425229.

- Bhatti, Y., A. L. Olsen, and L. H. Pedersen. 2009. “The Effects of Administrative Professionals on Contracting Out.” Governance 22 (1): 121–137. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.01424.x.

- Downs, A. 1957. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” The Journal of Political Economy 65 (2): 26–31. doi:10.1086/257897.

- Dubin, J. A., and P. Navarro. 1988. “How Markets for Impure Public Goods Organize: The Case of Household Refuse Collection.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 4 (2): 217–241. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jleo.a036951.

- Elinder, M., and H. Jordahl. 2013. “Political Preferences and Public Sector Outsourcing.” European Journal of Political Economy 30: 43–57. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2013.01.003.

- European, Commission. 2019. “Single Market Scoreboard.” Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs Brussels.

- Fernandez, S., J. E. Ryu, and J. L. Brudney. 2008. “Exploring Variations in Contracting.” The American Review of Public Administration 38 (4): 439–462. doi:10.1177/0275074007311386.

- Ferris, J. 1986. “The Decision to Contract Out: An Empirical Analysis.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 22 (2): 289–311. doi:10.1177/004208168602200206.

- Ferris, J., and E. Graddy. 1986. “Contracting Out: For What? with Whom?” Public Administration Review 46 (4): 332. doi:10.2307/976307.

- Fuentes-Bargues, J., M. Luis, C. González-Cruz, and G.-G. Cristina. 2017. “Environmental Criteria in the Spanish Public Works Procurement Process.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (2): 1–18. doi:10.3390/ijerph14020204.

- Grandia, J. 2016. “Finding the Missing Link: Examining the Mediating Role of Sustainable Public Procurement Behaviour.” Journal of Cleaner Production 124: 183–190. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.102.

- Guo, M., and S. Willner. 2017. “Swedish Politicians’ Preferences regarding the Privatisation of Elderly Care.” Local Government Studies 43 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1237354.

- Igarashi, M., L. De Boer, and O. Michelsen. 2015. “Investigating the Anatomy of Supplier Selection in Green Public Procurement.” Journal of Cleaner Production 108: 442–450. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.010.

- Jaehrling, K. 2015. “The State as a ‘Socially Responsible Customer’? Public Procurement between Market-Making and Market-Embedding.” European Journal of Industrial Relations 21 (2): 149–164. doi:10.1177/0959680114535316.

- Jensen, D. C., and L. B. Pedersen. 2017. “The Impact of Empathy-Explaining Diversity in Street-Level Decision-Making.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 27 (3): 433–449. doi:10.1093/jopart/muw070.

- Keulemans, S., and S. Van de Walle. 2017. “Cost-Effectiveness, Domestic Favouritism and Sustainability in Public Procurement.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 30 (4): 328–341. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-10-2016-0169.

- Konisky, D. M., J. Milyo, and L. E. Richardson. 2008. “Environmental Policy Attitudes: Issues, Geographical Scale, and Political Trust.” Social Science Quarterly 89 (5): 1066–1085. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00574.x.

- Lancsar, E., D. G. Fiebig, and A. R. Hole. 2017. “Discrete Choice Experiments: A Guide to Model Specification, Estimation and Software.” PharmacoEconomics 35 (7): 697–716. doi:10.1007/s40273-017-0506-4.

- Lancsar, E and Louviere, J. 2008. “Conducting Discrete Choice Experiments to Inform Health Care Decision Making: A User’s Guide.” PharmacoEconomics 26 (8): 661–77. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053–200826080–00004.

- Lindh, A., and I. J. Sevä. 2018. “Political Partisanship and Welfare Service Privatization: Ideological Attitudes among Local Politicians in Sweden.” Scandinavian Political Studies 41 (1): 75–97. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12109.

- Loosemore, M. 2016. “Social Procurement in UK Construction Projects.” International Journal of Project Management 34 (2): 133–144. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.10.005.

- Lubell, M., R. Feiock, and S. Handy. 2009. “City Adoption of Environmentally Sustainable Policies in California’s Central Valley.” Journal of the American Planning Association 75 (3): 293–308. doi:10.1080/01944360902952295.

- McCrudden, C. 2004. “Using Public Procurement to Achieve Social Outcomes”. Natural Resources Forum, no. 4. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00099.x.

- McFadden, D. 1974. “Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior.” In Frontiers in Econometrics, edited by P. Zarembka, 105–142. New York: Academic Press.

- Morettini, S. 2011. “Public Procurement and Secondary Policies in EU and Global Administrative Law.” In Global Administrative Law and EU Administrative Law: Relationships, Legal Issues and Comparison, edited by E. Chiti and B. G. Mattarella, 187–209. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Mouraviev, N., and N. K. Kakabadse. 2015. “Public–Private Partnership’s Procurement Criteria: The Case of Managing Stakeholders’ Value Creation in Kazakhstan.” Public Management Review 17 (6): 769–790. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.822531.

- OECD. 2019. “Government at a Glance 2019.” OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/8ccf5c38-en.pdf?expires=1594214798&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=7DDAD2458E812FEA960722A1A4466443.

- Opp, S. M., and K. L. Saunders. 2012. “Pillar Talk: Local Sustainability Initiatives and Policies in the United States-Finding Evidence of the ‘Three E’s’: Economic Development, Environmental Protection, and Social Equity.” Urban Affairs Review 49 (5): 678–717. doi:10.1177/1078087412469344.

- Osborne, M. J., and A. Slivinski. 1996. “A Model of Political Competition with Citizen-Candidates.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (1): 65–96. doi:10.2307/2946658.

- Otjes, S. 2018. “Pushed by National Politics or Pulled by Localism? Voting for Independent Local Parties in the Netherlands.” Local Government Studies 44 (3): 305–328. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1427072.

- Petersen, O. H., K. Houlberg, and L. R. Christensen. 2015. “Contracting Out Local Services: A Tale of Technical and Social Services.” Public Administration Review 75 (4): 560–570. doi:10.1111/puar.12367.

- Plantinga, M., K. de Ridder, and A. Corra. 2011. “Choosing whether to Buy or Make: The Contracting Out of Employment Reintegration Services by Dutch Municipalities.” Social Policy and Administration 45 (3): 245–263. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00767.x.

- Polk, J., J. Rovny, R. Bakker, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, and J. Koedam. 2017. “Explaining the Salience of Anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data.” Research and Politics 4 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1177/2053168016686915.

- Pollitt, C., and G. Bouckaert. 2017. “Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis into the Age of Austerity.” In Fourth Edi. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 388.

- Portney, K. E., and J. M. Berry. 2010. “Participation and the Pursuit of Sustainability in U.S. Cities.” Urban Affairs Review 46 (1): 119–139. doi:10.1177/1078087410366122.

- Puyvelde, S. V., R. Caers, C. D. Bois, and M. Jegers. 2016. “Managerial Objectives and the Governance of Public and Non-Profit Organizations.” Public Management Review 18 (2): 221–237. doi:10.1080/14719037.2014.969760.

- Ryan, M., J. R. Kolstad, P. C. Rockers, and C. Dolea. 2012. “User Guide with Case Studies: How to Conduct a Discrete Choice Experiment for Health Workforce Recruitment and Retention in Remote and Rural Areas.” World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/dceguide/en/.

- Schoute, M., T. Budding, and R. Gradus. 2018. “Municipalities’ Choices of Service Delivery Modes: The Influence of Service, Political, Governance, and Financial Characteristics.” International Public Management Journal 21 (4): 502–532. doi:10.1080/10967494.2017.1297337.

- Serritzlew, S. 2003. “Shaping Local Councillor Preferences: Party Politics, Committee Structure and Social Background.” Scandinavian Political Studies 26 (4): 327–348. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2003.00092.x.

- Sørensen, R., and A. H. Bay. 2002. “Competitive Tendering in the Welfare State: Perceptions and Preferences among Local Politicians.” Scandinavian Political Studies 25 (4): 357–384. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00076.

- Sundell, A., and V. Lapuente. 2012. “Adam Smith or Machiavelli? Political Incentives for Contracting Out Local Public Services.” Public Choice 153 (3–4): 469–485. doi:10.1007/s11127-011-9803-1.

- Testa, F., F. Iraldo, M. Frey, and T. Daddi. 2012. “What Factors Influence the Uptake of GPP (Green Public Procurement) Practices? New Evidence from an Italian Survey.” Ecological Economics 82: 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.07.011.

- Train, K. E. 2002. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Trammell, E., S. Abutabenjeh, and A.-M. Dimand. 2019. “A Review of Public Administration Research: Where Does Public Procurement Fit In?” International Journal of Public Administration 43 (8): 1–13. doi:10.1080/01900692.2019.1644654.

- Uyarra, E., J. Edler, J. Garcia-estevez, L. Georghiou, and J. Yeow. 2014. “Barriers to Innovation through Public Procurement: A Supplier Perspective.” Technovation 34 (10): 631–645. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2014.04.003.

- Walker, H., and S. Brammer. 2009. “Sustainable Procurement in the United Kingdom Public Sector.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 14 (2): 128–137. doi:10.1108/13598540910941993.

- Wang, X. H., C. Hawkins, and E. Berman. 2014. “Financing Sustainability and Stakeholder Engagement: Evidence from U.S. Cities.” Urban Affairs Review 50 (6): 806–834. doi:10.1177/1078087414522388.

- Wang, X. H., C. V. Hawkins, N. Lebredo, and E. M. Berman. 2012. “Capacity to Sustain Sustainability: A Study of U.S. Cities.” Public Administration Review 72 (6): 841–853. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02566.x.

- Young, S., S. Nagpal, and C. A. Adams. 2016. “Sustainable Procurement in Australian and UK Universities.” Public Management Review 18 (7): 993–1016. doi:10.1080/14719037.2015.1051575.

- Zafra-Gómez, J., A. Luis, M. López-Hernández, A. M. Plata-Díaz, and R. Juan Carlos Garrido. 2016. “Financial and Political Factors Motivating the Privatisation of Municipal Water Services.” Local Government Studies 42 (2): 287–308. doi:10.1080/03003930.2015.1096268.

APPENDICES

APPENDICES

Figure A2 Position of the Belgian parties on Chapel Hill scale.

APPENDICES

Table A1 Representativeness check.

APPENDICES

Table A2. Characteristics of politicians.