ABSTRACT

The study focuses on the challenges of the ageing population in Finnish public policies related to municipal structures and finances. First, we review how the impacts of the ageing population have been identified and how necessary policy responses and reforms of the municipal division in particular have been prioritised by recent central governments. Second, we evaluate how state grant policy has equalised the financial capabilities ofmunicipalities to cope with the financial consequences of the ageing population. Our findings indicate that ageing is believed to increase municipal expenditures because the demand for care services in particular is growing. The analysis also demonstrates that the state grant system is capable of substantially equalising the differences in tax bases and spending obligations between municipalities. Nevertheless, central governments have planned ‘big-bang reform proposals’, introducing a completely new tier of democratic government and regionalising the most burdensome welfare services of municipalities.

Introduction

Finland is one of the most rapidly ageing societies among OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries and, according to Pirhonen et al. (Citation2020), it is the fastest-ageing society in Europe. In 2000, 14.8% of the Finnish population was 65 and over, but in 2019, the share was 21.8%. The overall national statistics also show that the birth rate in Finland has declined worryingly, especially in recent years. Furthermore, urbanisation has made many outlying districts nearly empty, but the more recent migratory trend is that people are relocating from small and mid-sized cities to around ten growth centres.

Finland is an interesting case in local government studies. Municipalities hold a wide self-government while having the extensive delivery and funding responsibilities of centrally regulated public welfare services, including basic education, social services and health care. However, the ageing population and demographic decline are threatening the stability of this highly decentralised and municipalised welfare service system, as many municipalities have faced issues against their vitality and solvency.

The study focuses on the challenges of the ageing population in public policies related to municipal structures and finances. First, it finds out how the impacts of the ageing population have been identified and how necessary policy responses and reforms of the municipal division in particular have been prioritised by recent central governments. The reviews outline the major restructuring propositions that enable us to specify and compare the aspirations of the recent cabinets to adjust and radically change municipal structures and functions, and to summarise the realised development of municipal mergers and inter-municipal collaboration.

Second, the study reviews the financial health of local governments by comparing disposable revenues between municipalities with heavily aged and less-aged populations. The aim is to find out how central government policy towards local governments has equalised the financial capabilities of local governments to cope with the financial consequences of ageing.

Our analyses of government propositions to parliament show that, as the central governments have become increasingly concerned about the abilities of many municipalities to function and maintain local welfare systems, they have used compulsory municipal mergers, subsidised some voluntary mergers and increased statutory arrangements of inter-municipal collaboration as the major readjustment strategies to renew municipal organisations. However, the current central government feels that the country needs a radical reform of local public finances and service systems; therefore, it proposes the creation of new regional governments that will take responsibility for all municipal social services, health services and fire and rescue services.

The statistical analyses of the study show that the state grant system has been reformed and fine-tuned so that the present system recognises the financial problems associated with the ageing population and effectively equalises the fiscal preconditions of all municipalities.

Analytical framework

Disputing views of the optimal structures of government

Centralised and decentralised governmental structures are the extreme ends of an administrative continuum where centralised public service functions are considered to represent standardised and monolithic supply while municipalities inherently provide locally adjusted solutions. The European Charter of Local Self-Government mandates that public responsibilities shall generally be exercised, in preference, by the authorities which are closest to the citizen. This has been interpreted to prioritise locally decentralised political and administrative structures through municipalities as small as possible. The ultimate justification for municipalities is based on political theory arguing that local governments are not simply organisations of public service delivery; they must also secure public interest by facilitating representative democracy and enabling the participation of local residents (Bailey Citation1999).

Fiscal federalism looks for an optimal division of duties between different tiers of government and argues how taxation, inter-governmental grants, spending competences and regulatory powers should be allocated to national, regional and local governments. The normative theory of fiscal federalism argues how to share state and local functions according to the aim of promoting the efficient allocation of a nation’s resources for both production and consumption – ‘allocative efficiency’ (Bailey Citation2008). Municipalities have a high potential in allocative functions by responding to local market failures, and by default, a decentralised service structure is considered to support allocative efficiency by enabling the production of public services to match the preferences of local citizens. However, the disadvantages of local decentralised service systems are their limited economies of scale and difficulty in exercising strategically co-ordinated public policies (Bailey Citation1999, Citation2008). The criterion of revenue adequacy and fiscal needs states that the ability to collect taxes should match the needs for budgetary expenditures as perfectly as possible in order to have fit-for-purpose accountability mechanisms (Oates Citation1972).

Public choice theorists have argued that if public services are divided between several tiers of government, the relative costs and achievements of each tier become transparent, allowing residents to make separate judgements and allocate their electoral support and payments of taxes accordingly. Having a large number of multi-purpose local authorities are considered to promote public interest by maintaining inter-local competition, enabling citizens to make choices and empowering local residents to participate in and learn democratic processes and take financial responsibility for collective decisions. These arguments are associated with the famous Tiebout model, assuming that a highly fragmented structure of local governments is a market-type condition creating competitive pressures to local policymakers to attract mobile families and enterprises as new taxpayers (Boyne Citation1997; Briffault Citation1996).

Advocates of large-scale local authorities diminish the benefits of inter-municipal competition as they consider that merged municipalities essentially enhance the economic efficiency of public duties; this enables economies of scale to be gained in service production and externalities of municipal actions to be internalised. Anyway, the claimed benefits are not undisputed since many international empirical studies have not been able to demonstrate cost savings or benefits of that sort as the direct impacts of municipal mergers (Bish Citation2000 ref by Dollery and Johnson Citation2005; Roesel Citation2017; Lüchinger and Stutzer Citation2002). Opponents of municipal amalgamation point out that mergers have adverse impacts on local democracy by weakening effective representation and robust citizen participation and making the societal engagement of local communities more complex (Dollery and Johnson Citation2005; Boyne Citation1997). However, an appropriate local government structure has remained an unsettled issue not only in political science but also in public sector economics (Bailey Citation1999).

The paradox of the decentralised Nordic countries

The Nordic countries are so-called welfare states in which constitutions define the basic and equal economic, social and educational rights of citizens. The specific and relatively abundant entitlements of citizens are indicated through welfare legislation, which also demonstrates the statutory service duties of local and regional governments (Kröger Citation2011).

The Nordic countries are said to be the most decentralised among the European countries as their municipalities provide and fund most of the welfare and community services (Mäkinen Citation2017; Reichborn-Kjennerud and Vabo Citation2016). The ultra vires doctrine is not applied, as local governments have general powers that also enable them to provide various voluntary services to local residents. Wide local self-government is a long Nordic tradition, and in Finland, it is strongly guaranteed by the constitution of the country (Mäkinen Citation2017).

The paradox of the decentralised welfare countries is that self-government allows local choices and priorities, but the welfare schemes and services aim to provide equal benefits for all citizens. The paradox urges supervision of the applied decentralised public policies while creating conflict between the central government and regional and local governments. The decentralised administrative structures also need continuous stabilisation measures, but at the same time, they are exposed to various re-structural or rescaling aspirations (Mäkinen Citation2017; Kröger Citation2011).

The position of local governments is pronounced in Finland, as it is one of the few EU Member Countries whose public administration is organised by only two tiers of democratic government: central government and the municipalities. Finnish municipalities are responsible for providing public social welfare, education (except university education), culture, technical infrastructure and local public utility services, and unlike in the Scandinavian countries, Finnish municipalities are also responsible for organising and funding public health services. Due to the intense decentralisation and relatively small size of the municipalities (the median Finnish municipality has only approximately 6,100 inhabitants), municipalities’ societal role is remarkable but heavy.

Municipal taxation and the financial equalisation of municipalities

The Finnish municipalities’ self-government is also guaranteed by the municipal taxation powers highlighted in . Nordic municipal taxation is essentially based on an income tax, which is also the main source of municipal revenues in Finland. Furthermore, municipalities have the power to tax property owners (i.e., of real estate), but the share of property tax revenues among all municipal revenues is relatively small. Municipalities do not have the power to tax enterprises. Instead, they receive a share of the national corporate tax revenues, but these tax revenue streams have been unstable because of responsiveness to business cycles and tax policy changes.

Table 1. Municipal autonomous taxation powers

As the differences between municipalities’ revenues and cost factors have been remarkable, the revenue adequacy criterion is arranged through a state grant system providing grants that cover approximately 20% of the total municipal revenues. For a long time, earmarked specific grants to local authorities were bound by laws and regulations limiting local autonomy in practice before major reforms that transferred former earmarked grants to general grants took place in the 1980s and 1990s. In Finland, this reform happened in 1993, with the introduction of a grant system that consisted of equalisation schemes that levelled off differences in tax revenues and spending needs between municipalities (Oulasvirta Citation1997; Moisio, Loikkanen, and Oulasvirta Citation2010). There were also some other regulatory reforms, giving more power to local politicians to decide and allocate money according to local preferences. These reforms gave more leeway to realise the well-known potential benefits of decentralisation (Oates Citation1972, Citation2005).

Based on the spending needs criteria, each municipality has its own calculatory costs in the equalisation of municipal spending needs. All municipalities have the same financing share (€3599/inhabitant for the year 2018) of their calculated service costs. Formally, this is full equalisation between their own financing shares per capita and their calculatory service costs, which vary between municipalities based on their spending needs. If the real costs are higher than the calculated costs, this part gets no equalisation. If the real costs are lower than the calculated costs, the municipality still gets the whole grant (in other words, the difference between calculatory service costs and their own financing share per capita). This is an incentive to economise service production because the efficiency benefit is not cancelled via a corresponding grant decrease. The problem is that the state has raised the municipalities’ self-financing share in recent years. If cabinets cut grants to low levels, then equalisation with grants will lose its force.

Revenue equalisation is operated by the Ministry of Finance, which equalises calculatory tax revenues that the municipality could raise if it used the country’s average tax rates on taxable personal incomes and property tax bases. Revenue equalisation comprises municipal income tax, municipal property (real estate) tax, and the municipalities’ share of corporate tax revenues. The revenue equalisation guarantees all municipalities 80% (compensation level of 80%) of the average per capita calculatory tax revenues (threshold of 100%) as a supplement to their block grants. Municipalities whose calculatory tax revenue is above the threshold must pay 37% as well as an additional percentage based on a logarithm of the surplus amount to the funding as a reduction in their block grants (Moisio, Loikkanen, and Oulasvirta Citation2010; The law of state grants to municipal basic services 29.12.Citation2009/1704).

Materials and methods

We performed document analyses by reviewing official documents of the state government. The documents included law-drafting materials, especially governmental propositions to parliament from 1992 to 2019 published in full text in Finlex, an online database of Finland’s Ministry of Justice. In these thematic reviews, we identified how the impacts and associated risks of the ageing society’s development had been articulated by central governments and what kinds of structural rescaling measures have been prioritised. We also compiled statistical data from municipal central associations to illustrate the incurring of debt and the realised structural changes of the municipal sector.

Then, using financial data and demographic statistics from Statistics Finland (Citation2020) and the Association of Finnish Regional and Local Authorities, we analysed the financial positions and service costs of different municipalities and the relationships between their demographic characteristics and their disposable tax and grant revenues. We divided municipalities into four groups according to the percentage of older people among the general population and calculated the averages of several variables in these four groups (). We also calculated correlations and ran regression analyses (ordinary least squares, OLS) using the SPSS statistical software. In our first regression model, the dependent variable was the disposable tax and grant income per inhabitant, and in the second model, it was the surplus per inhabitant. The independent variables of the calculated regression models included mainly age and other population-based indicators, which are central factors associated with the financial capacity of municipalities.

Recognition of the ageing society development

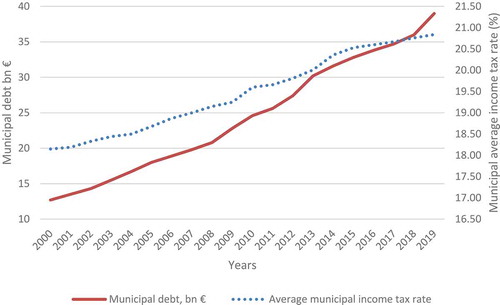

According to some previous studies, the Finnish welfare state policies implemented through local authorities have met with growing problems. The deteriorating dependency ratio, uneven migration flows and different unemployment rates increasingly differentiate the service needs and abilities to collect local taxes between areas (Moisio, Loikkanen, and Oulasvirta Citation2010; Sjöblom Citation2020). The financial difficulties of local governments have increased, but their own means of responding to these challenges have remained limited, meaning that increases in tax rates and debt are the only potentially powerful revenue-based coping strategies (Nelson Citation2012; Ladner and Soguel Citation2015). highlights that municipal debt has more than tripled within two decades in Finland. The OECD (Citation2018) has also emphasised that Finnish public finances are under pressure from the rapidly ageing population, increasing public expenditures, while globalisation and high unemployment and low employment rates create challenges in raising revenues.

According to our document analyses, the ageing population as a societal trend has been a source of serious concerns for recent cabinets, as it has been referred to in many governmental propositions to parliament (e.g. government bills to parliament). The development has been associated with the decreasing birth rate and the improving longevity of the population, while urbanisation and selective migration have been named as parallel phenomena, making small and rural local authorities and the Eastern and Northern parts of the country the worst-hit areas.

Recent central governments have considered that the ageing society’s development increases demand for services, especially social and health services, accelerates the retirements of municipal workers, increases the demand for new municipal recruitment even though it may be difficult to find new workforces in service industries, increases municipal service costs and expenditures and causes difficulties in controlling municipal expenditures. In contrast, the ageing society’s development also decreases demand on municipal education services. For example, in 2000, there were 4,009 comprehensive (primary and elementary) schools, compared to 2,279 in 2019.

Central governments have articulated varied public policy measures to change fiscal and related policies and how public authorities are organised and operate. They are considered a necessary means of coping with the ageing population. Creating economic growth and improving cost-effectiveness and productivity are often named as vital but very generic policy measures for responding to the development. A remarkable and general reform directly associated with these aims was a new pension system, which passed parliament in 2015. The earliest eligibility age for old-age pension was raised from 63 to 65, and the forthcoming eligibility age for old-age retirement was linked to life expectancy. It's widely expected that the reform will extend work careers. According to the latest pension reports, average work careers became 3.4 years longer between 2000 and 2018 (Finnish Centre for Pensions Citation2019). Our analyses of government proposals also revealed that more specific but reasoned coping means would be the diversification of public service supply, digitalisation of municipal services, increased use of services on wheels, home help services, itinerants, and better utilisation of voluntary workers.

Ageing motivates efforts to consolidate municipal structures

Central governments have persistently focused on local government structures, while some members of the political elite have, from time to time, claimed that the municipal division is outdated, providing low value for money. The governmental proposals to parliament have included explicit and enhanced demands to renew the municipal division, increase inter-municipal collaboration and create wider catchment areas of municipal services. These reformist tendencies have accumulated into major reorganisation proposals based on the fundamental idea of consolidating and unifying the local government structures summarised in . These proposals are accompanied by an OECD (Citation2018) survey arguing that municipal social and health services suffer from inefficiencies partly because the service system is fragmented as statutory service responsibilities are decentralised to many autonomous local authorities.

Table 2. Proposed and implemented regionalisation reforms as a response to the ageing society and related developments

As demonstrates, the central government’s plans have been successive and ambitious. The Municipal and Service Structure Reform was a fixed-term national reform programme between 2007 and 2011 that successfully delivered voluntary municipal amalgamations by providing state government merge subsidies. By contrast, a couple of subsequent reform proposals have not been successful. The Social and Health Care Reform was the first proposal, which totally failed in 2015 (Valkama, Asenova, and Bailey Citation2016). However, the architects of the proposals considered that the potential impacts of the ageing population may be so serious that the municipal-based system of public welfare services would not be able to cope adequately. The next and even larger fiasco was the Regional Government, Health and Social Services Reform, which included a radical proposal to regionalise municipal social, health, fire, rescue and some other services by creating new, democratic and semi-autonomous regional governments and expanding the freedom of choice of patients, including inter alia the wider use of service vouchers and the introduction of personal care budgets.

The newest reform proposal, given to parliament in 2020, also includes a scheme for the regionalisation of municipal social, health, fire and rescue services through new regional governments. The proposal has many similar elements to the previously failed proposal, but this time the plans to expand the residents’ freedom of choice are excluded.

As demonstrates, the central government has evaluated the impacts of the ageing population quite consistently by highlighting the growing demand for social and health care and increasing public expenditures. The potentially increasing inequalities among citizens have distressed the cabinets, as they have considered uneven regional development as a probable and very serious threat to society, jeopardising the egalitarian distribution of basic welfare. A common feature of the proposed and implemented reorganisation reforms has been a shared vision that the unification and consolidation of municipal services and structures is a solution, but the cabinets have had differences concerning the form, scope and scale of regionalisation and the powers of local residents as service customers.

Municipal mergers and development of inter-municipal collaboration

With Finland being the most sparsely populated country in the EU, the fundamental structural problem of local governments has been their small size (Bailey Citation1999). This long-term problem has been addressed by municipal mergers and inter-municipal collaboration. The mergers have been either voluntary or compulsory (i.e. top-down), for example, in the 1970s and again in 2014–2015, but this conceptual classification is somewhat rough or artificial. Namely, the central governments initially granted cost compensations and more recently special incentive grants to wheedle municipalities, at least formally, into voluntary mergers. The valid incentive grants are discretionary, in other words non-automatic, but some argue that state-funded subsidies are necessary because there is a need to consolidate municipal structures, especially because of the ageing population and the pressures of public finances. demonstrates how the number of municipalities developed from 1972 to 2017.

Table 3. Development of the number of municipalities, average population size of municipalities, voter turnout in municipal elections, share of urban municipalities, and number of joint municipal authorities between 1972 and 2017 (Statistics Finland Citation2020; The association of finnish local and regional authorities Citation2020)

According to empirical studies, municipal mergers have not delivered the expected savings on municipal spending. Vartiainen (Citation2015) and Saarimaa and Tukiainen (Citation2018) compared changes in the expenditures of merged municipalities and non-merged comparable municipalities and could find no evidence of cost savings with municipal mergers. Furthermore, Saarimaa and Tukiainen (Citation2015) demonstrated that mergers generate considerable one-off extra expenditures since municipalities seem to hastily spend money between the amalgamation decision and the actual amalgamation.

As, practically, all municipalities have been too small to take care of the most demanding welfare duties, the legislature already made inter-municipal collaboration compulsory a long time ago, as so-called statutory joint municipal authorities (sometimes called joint municipal boards) were introduced for the first time in 1948 to improve the economies of scale of special health care. Later on, the use of these bodies was also made compulsory in regional planning and development and in the care of disabled people. Besides compulsory joint municipal authorities, municipalities have established some voluntary joint municipal authorities especially around local public utilities. However, the system of inter-municipal organisations has proven to be fragmentary and asymmetric (Mäkinen and Niemivuo Citation2014; Anttiroiko and Valkama Citation2017). Nevertheless, demonstrates that the system has also had some flexibility, as the number of the joint municipal authorities has scaled up and down during previous decades.

The Municipal and Service Structure Reform extended inter-municipal collaboration by introducing statutory catchment areas in social and basic health care, but it also opened up an avenue for more flexible methods of collaboration through contractual commitments without the creation of separate legal entities. A special host municipality contract model was legalised, which means an outsourcing arrangement between local authorities combined with a shared governance system through a joint political committee with a co-ordination function.

Effective fiscal equalisation of municipalities

We analysed the financial health of municipalities against municipal classes consisting of heavily aged municipalities, two medium classes regarding ageing and against the most favourable class of municipalities with a less-aged population. We used the financial health figures applied in Finland when assessing the financial health of municipalities: income tax rate (the main tax source of municipalities), accrued deficit or surplus and the debts of the municipal group. In these analyses, we used consolidated debts per inhabitant because municipalities have divided tasks differently between their own core organisation and municipally owned enterprises and other service producers. This combined (e.g. group) figure can be considered as a better indicator of local government solidity.

The average key financial figures do not differ greatly between the groups of municipalities. However, the accrued surplus per inhabitant is largest in the municipalities with the most aged people. It seems that, in this least favourable group, the equalising grant system added to the municipalities’ own financial management policies is able to effectively compensate for the cost difference.

Although it is mostly aged municipalities that have confronted the strongest depopulation () and highest social and health care expenditure per inhabitant (), their key financial ratios are not worse () than those of other municipalities with more favourable conditions. This is an elementary finding in our study, its key reason being the strong equalisation effect of state grants on municipalities.

Table 4. Municipalities classified by the size of the old people’s group and some averages of financial variables of year 2019. (Source: Statistics Finland and the association of Finnish regional and local authorities, elaborated by the authors)

Table 5. Municipalities classified by the size of the old people’s group and some averages of current costs per inhabitant of year 2019. (Source: Statistics Finland and the association of Finnish regional and local authorities, elaborated by the authors)

Table 6. Municipalities classified by the size of the old people’s share and some averages of demographic variables of year 2019. (Source: Statistics Finland and the association of Finnish regional and local authorities, elaborated by the authors)

The equalising power of the grant system is illustrated in . Municipalities with the largest share of old people also have the highest grant and tax income per inhabitant.

Table 7. Municipalities classified by the size of the old people’s group, tax income and grant income of year 2019. (Source: Statistics Finland and the association of Finnish regional and local authorities, elaborated by the authors)

The revenue equalisation system, which provides 80% of the average per capita calculatory tax revenues for all municipalities, supplements municipalities’ block grants based on spending needs. Spending needs equalisation is financed by the central government, while tax revenue equalisation is financed partly by local governments. The basic services block grant uses the following criteria for social and health care and elementary school services: sizes of variable age groups,Footnote1 unemployment and the morbidity rate of municipal inhabitants. Additional criteria are bilingual inhabitants, inhabitants with foreign language, island municipality, population density and low educational background.

The block grants for factors other than basic education and culture are based on the following criteria: for secondary and vocational schools, the criteria include calculative cost €/student varying between institutions and study programmes; other cultural institutions (museums, theatres, orchestras, etc.) and youth and sports activities are based on €/inhabitant or €/hour of teaching or €/person labour year.

Especially in the block grant for social and health care, the age group of old people carries a strong weight. The combined group consisting of the three oldest groups of people have a 39% weight, and the 85 or older group has a weight of 28% of the calculated municipal basic social and health care and related expenses of which the grant is a share that is the same for all municipalities. This explains the strong equalising effect favouring municipalities with a disadvantageous age structure. The correlations give concentrated information on the variation between grant income per inhabitant and other variables ().

Table 8. Correlations between grant income per inhabitant and other variables

The larger the share of old people (people 65 or older) and the higher the income tax burden (rate) in the municipality, the more grant income per inhabitant the municipality has. This overall picture of correlations supports our observation of the strong equalisation effect of the grant system in relation to the ageing phenomenon. The share of old people was also the strongest explanatory factor for grant money in a regression analysis with the same variables as the independent variables (not shown here).

The share of old people was also the strongest explanatory factor for the combined variable of tax and grant income per inhabitant ().Footnote2 The combined variable shows the main money source of municipalities (basic income) that is usable for social and health care and other obligatory tasks. With this regression analysis, we show that the age variable has a strong impact on the available main money resources per inhabitant in Finnish municipalities.

Table 9. Regression model (ordinary least squares) of the dependent variable of combined tax and grant income per inhabitant. Data for variables were collected from the 2019 municipal statistics of the association of Finnish local authorities

If the equalisation mechanism is efficient towards local governments, those municipalities with unfavourable circumstances and high spending needs caused by service provision will end up with a higher level of tax and grant money than those with favourable circumstances and relatively lower spending needs.

The results of the regression analysis show that the size or population density of the municipality does not explain the amount of tax and grant money per inhabitant. Furthermore, the income tax rate (variation range 16.5–22.5%) and all other variables except the surplus variable explain less than the share of old people.

Inhabitants with a foreign language is a variable that has a negative coefficient. Immigrants live mainly in big cities. In the whole equalisation system (consisting of both tax equalisation and spending needs equalisation) they end up as either net payers or modest net receivers. The coefficient should not be negative when the other variables are controlled, if the size measured with inhabitants is included, and if the grant system compensates for the spending needs of people with foreign languages.

The Nordic model of the equalisation policy is an important institutional factor. Reducing differences between municipalities helps all municipalities to have quite the same possibilities to provide basic welfare services: municipalities with the highest ageing problems also have more basic income per inhabitant to cope with their heavy social and health care costs.

We also ran a regression analysis using the accrued surplus per inhabitant as a dependent variable. , which also includes multicollinearity tests with acceptable results, shows that the share of old people also explains (with a positive coefficient) the financial condition.

Table 10. Accrued surplus per inhabitant in municipalities explained with a regression analysis (OLS). Data for variables collected from the 2019 municipal statistics of the association of Finnish local authorities

Discussion and conclusion

Municipal finances have become increasingly unsustainable in recent decades in terms of both intergenerational equity and autonomous financial capacity. Municipal tax rates have risen and municipalities have run into debt while the share of 65 and over population has increased substantially. Although the municipal sector will receive some perceptible relief from the pension reform of 2017, which raises the retirement age and links it to life expectancy, it is widely believed that the fiscal stress of the municipalities will not only continue in general but also worsen in some particular municipalities.

Finnish national and local policymakers have responded to the pressures of municipalities by merging them, which has closed down the operations of many small and rural municipalities that are too small to survive alone in financial hardships. However, it is difficult to demonstrate methodologically how much the ageing population as such has contributed to local merging decisions, as many marginalised municipalities have also suffered a rapid decline of classic industries and outmigration.

Our findings also demonstrate that state-run policies of shared services have become more dominant as the obligatoriness of inter-municipal collaboration has increased. These findings parallel some other studies that have reported strengthened state control (Kröger Citation2011) and statutorily increased use of cooperative municipal services (Sjöblom Citation2020; Anttiroiko and Valkama Citation2017). The Finnish municipal restructuring strategy has progressed in the opposite direction of the public choice preference associated with the advantages of inter-municipal competition, as the municipal mergers have cut down the number of municipalities, and municipal-municipal collaboration has woven local interests together. These developments are similar to other European countries which have had many small municipalities (Lowndes and Gardner Citation2016; Baldersheim and Rose Citation2010).

Interestingly, our study shows how the strong grant policy gives even poorer and ageing municipalities about the same financial starting points as others. We were able to identify that, although a large number of Finnish municipalities suffer one way or another from declining demographics, there are no remarkable differences in the financial ratios between the municipality groups. So far, the country has avoided the strong polarising effect observed, for example, in the United Kingdom (Gray and Barford Citation2018). Municipalities have increased their tax rates and collected more debt funding, but this has happened quite evenly in all municipalities. We are able to explain this by the state grant system, as it includes a strong equalisation of the tax base and spending needs between municipalities (Oulasvirta and Turala Citation2009).

The adaptive division of municipalities, scalable structures of inter-municipal organisations, flexible forms of shared services and the strongly equalising grant system have been effective and balancing policy instruments in the case of Finland. Together, these instruments have helped to avoid the phenomena of depopulation and ageing that cause radical polarisation in key financial health ratios. However, we must notice that even if financial health ratios are not distressingly polarised, the accessibility of health services has begun to differentiate regionally to a worrying degree (MDI Citation2020).

Our findings also suggest that the renewal of the municipal structures has been such a slow and modest process – including compulsory, state-subsidised and fully voluntary mergers of municipalities and inter-municipal organisations – that the recent central governments have considered that more fast-acting and profound actions are necessary. National politicians acknowledge that the phenomena of the ageing population and demographic decline, especially due to a record low birth rate, are fundamentally changing society and are even somewhat existential threats to the welfare state model based on municipal funding and delivery of welfare services. All the recent central governments have identified the consequences of the ageing population in very similar ways, but their implemented and proposed public policy responses have differed, thus far illustrating incompatibilities in the preferences between political parties and national, regional and local interests. Like the previous government, the current government also plans to replace public social, health, fire, and rescue services currently run by local governments and joint municipal authorities with regionalised service systems.

The proposed big-bang reform does not necessarily change the constitutional position of local governments as democratic, multi-purpose and self-governing institutions with powers to levy taxes, but municipalities would have to somehow reinvent themselves as strongly streamlined local public authorities since the possible regionalisation would transfer a considerable part of municipal duties, revenues and expenditures to the new regional governments. The reform would radically change the classic character of the decentralised welfare state, and local authorities would need to reconceptualise not only their welfarist but also their policy-making role within the new system of three democratic governmental tiers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pekka Valkama

Pekka Valkama is an associate professor of social and health management. He is also associated with the studies of digital economy in the School of Management at the University of Vaasa, Finland. His research has focused on financial management and he has published recently in Voluntary Sector Review (2020), Financial Accountability and Management (2019), and Case Studies in Transport Policy (2018).

Lasse Oulasvirta

Lasse Oulasvirta is a professor of public sector accounting in the Faculty of Management and Business at Tampere University, Finland. He researches public sector and local government financing, budgeting and auditing, and has recently published articles on local government risk management (Local Government Studies, 2017), accounting principles and harmonisation in the public sector (Public Money and Management, 2021), and chapters in the book European Public Sector Accounting (Coimbra University Press, 2019).

Notes

1. The age groups are: 0–5, 6, 7–12, 13–15, 16–18, 19–64, 65–74, 75–84, and 85 years old and older people.

2. Number of inhabitants and share of children were removed from the model because of strong multicollinearity. The number of inhabitants correlated with the percentage change of the population and the share of children with the share of old people. Several different models were tried, and the share of old people had a positive significant coefficient in all of them.

References

- Anttiroiko, A.-V., and P. Valkama. 2017. “The Role of Localism in the Development of Regional Structures in Post-war Finland.” Public Policy and Administration 32 (2): 152–172. doi:10.1177/0952076716658797.

- Bailey, S. J. 1999. Local Government Economics. Principles and Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- Bailey, S. J. 2008. “The Rationale for Regional Government within the EU: Function, Form and Finance.” In Decentralisation and Regionalisation: The Slovenian Experience in an International Perspective, edited by S. Setnikar-Cankar and Z. Sevic, 109–127. London: Greenwich University Press.

- Baldersheim, H., and L. E. Rose. 2010. Territorial Choice: The Politics of Boundaries and Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bish, R. L. 2000. Local Government Amalgamations: Discredited Nineteenth-century Ideals Alive in the Twenty-first. Toronto: Howe Institute.

- Boyne, G. A. 1997. “Public Choice Theory and Local Government Structure: An Evaluation of Reorganisation in Scotland and Wales.” Local Government Studies 23 (3): 56–72. doi:10.1080/03003939708433876.

- Briffault, R. 1996. “The Local Government Boundary Problem in Metropolitan Areas.” Stanford Law Review 48 (5): 1115–1171. doi:10.2307/1229382.

- Dollery, B., and A. Johnson. 2005. “Enhancing Efficiency in Australian Local Government: An Evaluation of Alternative Models of Municipal Governance.” Urban Policy and Research 23 (1): 73–85. doi:10.1080/0811114042000335278.

- Finnish Centre for Pensions. 2019. “Eläkkeellesiirtymisikä Työeläkejärjestelmässä vuonna 2018.” Accessed 7 August 2020. https://www.sttinfo.fi/data/attachments/00781/3964dd51-f257-4fd2-b9cc-6779ab238295.pdf

- Gray, M., and A. Barford. 2018. “The Depths of the Cuts: The Uneven Geography of Local Government Austerity.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (3): 541–563. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy019.

- Kröger, T. 2011. “Retuning the Nordic Welfare Municipality: Central Regulation of Social Care under Change in Finland.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 31 (3/4): 148–159. doi:10.1108/01443331111120591.

- Ladner, A., and A. Soguel. 2015. “Managing the Crises – How Did Local Governments React to the Financial Crisis in 2008 and What Explains the Differences? the Case of Swiss Municipalities.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 81 (49): 752–772. doi:10.1177/0020852314558033.

- Lowndes, V., and A. Gardner. 2016. “Local Governance under the Conservatives: Super-austerity, Devolution and the ‘Smarter State’.” Local Government Studies 42 (3): 357–375. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1150837.

- Lüchinger, S., and A. Stutzer. 2002. “Skalenerträge in der öffentlichen Kernverwaltung. Eine empirische Analyse anhand von Gemeindefusionen.” Swiss Political Science Review 8 (1): 27–50. doi:10.1002/j.1662-6370.2002.tb00333.x.

- Mäkinen, E. 2017. “Controlling Nordic Municipalities.” European Public Law 23 (1): 123–147.

- Mäkinen, E., and M. Niemivuo. 2014. “Perustuslakivaliokunnalle: Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Sosiaali- Ja Terveydenhuollon Järjestämisestä Sekä Eräiksi Siihen Liittyviksi Laeiksi.” (HE 324/2014 vp).

- MDI 2020. “Uusien Hyvinvointialueiden Alueanalyysi – Hyvinvointialueet Jakaantuvat Alueellisten Erojen, Alueprofiilin Ja Väestöpohjan Perusteella Neljään Ryppääseen.” 7.11.2020. Accessed 13 November 2020. https://www.mdi.fi/tiedote-uusien-hyvinvointialueiden-alueanalyysi-hyvinvointialueet-jakaantuvat-alueellisten-erojen-alueprofiilin-ja-vaestopohjan-perusteella-neljaan-ryppaaseen/

- Moisio, A., H. A. Loikkanen, and L. Oulasvirta. 2010. “Public Services at the Local Level – The Finnish Way.” VATT Policy Reports 2/2010, Government Institute for Economic Research.

- Nelson, K. L. 2012. “Municipal Choices during a Recession: Bounded Rationality and Innovation.” State and Local Government Review 44 (1S): 44–63. doi:10.1177/0160323X12452888.

- Oates, W. E. 1972. Fiscal Federalism. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Oates, W. E. 2005. “Toward a Second-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism.” International Tax and Public Finance 12 (August): 349–374. doi:10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9.

- OECD. 2018. OECD Economic Surveys: FINLAND. February 2018. Paris: OECD.

- Oulasvirta, L. 1997. “Real and Perceived Effects of Changing the Grant System from Specific to General Grants.” Public Choice 91 (3/4): 397–416. doi:10.1023/A:1004987824891.

- Oulasvirta, L., and M. Turala. 2009. “Financial Autonomy and Consistency of Central Government Policy Towards Local Governments.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 75 (2): 311–332. doi:10.1177/0020852309104178.

- Pirhonen, J., L. Lolich, K. Tuominen, O. Jolanki, and V. Timonen. 2020. “These Devices Have Not Been Made for Older People’s Needs – Older Adults’ Perceptions of Digital Technologies in Finland and Ireland.” Technology in Society 62: 101287. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101287.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., and S. I. Vabo. 2016. “Extensive Decentralisation – But in the Shadow of Hierarchy.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Decentralisation in Europe, edited by J. Ruano and M. Profiroiu, 253–272. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roesel, F. 2017. “Do Mergers of Large Local Governments Reduce Expenditures? – Evidence from Germany Using the Synthetic Control Method.” European Journal of Political Economy 50: 22–36. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.10.002.

- Saarimaa, T., and J. Tukiainen. 2015. “Common Pool Problems in Voluntary Municipal Mergers.” European Journal of Political Economy 38: 140–152. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.02.006.

- Saarimaa, T., and J. Tukiainen. 2018. “PARAS-hankkeen Aikana Toteutettujen Kuntaliitosten Vaikutukset.” Kansantaloustieteellinen Aikakauskirja 114 (2): 256–271.

- Sjöblom, S. 2020. “Finnish Regional Governance Structures in Flux: Reform Processes between European and Domestic Influences.” Regional & Federal Studies 30 (2): 155–174. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1541891.

- Statistics Finland. 2020. Statistical databases, Accessed 6 March 2020. https://www.stat.fi/index_en.html

- The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities. 2020. Suomen kaupungit ja kunnat. Kaupunkien ja kuntien lukumäärät ja väestötiedot. Accessed 9 September 2020. https://www.kuntaliitto.fi/tilastot-ja-julkaisut/kaupunkien-ja-kuntien-lukumaarat-ja-vaestotiedot

- The law of state grants to municipal basic services 29.12.2009/1704.

- Valkama, P., D. Asenova, and S. J. Bailey. 2016. “Risk Management Challenges of Shared Public Services: A Comparative Analysis of Scotland and Finland.” Public Money and Management 36 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1080/09540962.2016.1103415.

- Vartiainen, N. 2015. “Kuntaliitosten Taloudelliset Vaikutukset – Tutkimus Vuosina 2003-2007 Toteutettujen Kuntaliitosten Vaikutuksista Liitoskuntien Nettokustannuksiin.” Kunnallistieteellinen Aikakauskirja 43 (1): 37–59.