ABSTRACT

Local turnout has declined in many European countries, posing challenges to the inclusiveness and representativeness of elections. One response proposed to address this challenge are franchise extensions to new groups of voters. Distinguishing between horizontal extensions to non-national EU-citizens and vertical extension to 16- to 18-year-olds, we analyse their effects on voter turnout in the context of German local council elections. The country’s federal system enables us to analyse the effects on voter turnout in 13 states from 1978 until 2019. We find that the horizontal franchise extension is associated with a subsequent drop in overall turnout at German local council elections. By contrast, vertical franchise extensions do not affect turnout. The findings temper expectations concerning the ability of local franchise extensions to boost democratic legitimacy via increased participation.

Introduction

In 2011, Marshall, Shah, and Anirudh (Citation2011) found the field of local elections underresearched, leaving many questions unanswered. While research has since caught up, the picture remains incomplete and fragmented. Acknowledging the importance of local elections in today’s multi-level democracies, Gendźwiłł and Steyvers (Citation2021, 2) have recently observed that ‘[i]nsights in the patterns and dynamics of local elections and voting can thus still be considered as a missing link in the study of multilevel elections’. One of the missing links regarding local elections refers to turnout and turnout change. Until today, research on turnout change has focused mainly on first-order elections. Prominent studies have investigated the role of generational change, changes in mobilising agencies, the increasing number of elective institutions, or institutional reform to explain declining trends across many advanced democracies (Kostelka and Blais Citationforthcoming, 3–5). But declining turnout is not confined to first-order elections. The same trend can be observed for local elections across many European countries (van der Kolk Citation2019). Looking at the German case, we investigate whether one of the most prominent institutional explanations for turnout decline – namely franchise extensions – helps to understand local turnout decline in Germany, an explanation that might also hold for many other European countries where the same trend can be observed. In Germany, voters in approximately 11,000 municipalities elect local councillors every four to five years. As expected for second-order contests, local election turnout in Germany has always been lower than turnout for federal elections (Bundestagswahlen). But since the beginning of the 1990s the gap has widened considerably. While the gap was around 10 percentage points in the beginning of the 1990s, it was about 27 percentage points during the years 2002–2006. By 2015, average turnoutFootnote1 in local elections across all German states had fallen to around 50%.

Table 1. OLS-regressions of relative change in local election turnout.

Declining turnout levels at local elections might reflect the declining importance of local politics in the eyes of voters (Wood Citation2002), thereby becoming even more second-order than they were. Alternatively, however, turnout decline might result from institutional changes. One such factor might be franchise extensions: Since the second half of the 19th century, successive extensions of the franchise to less propertied and/or less educated males and eventually to females have gradually shifted electoral inclusion towards the Dahlian ideal of full enfranchisement of all adult citizens. The reforms were intended to increase the congruence between the set of people entitled to participate in the making of collectively binding decisions and the set of people bound by these decisions by virtue of living in a certain area (town or city, region, or country). In the Western democracies, major franchise extensions to women and workers were largely completed during the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote2 After many countries lowered the voting age from 21 to 18 during the 1970s, the question of the franchise seems to have been settled. However, in 1992, a major electoral reform occurred in all member states of the European Union. With the Maastricht Treaty the member states agreed to grant the franchise to non-national EU citizens in local elections (Council Directive 94/80/EC).Footnote3 In addition, many European countries today are considering further extension of the franchise to 16- and 17-year-olds. In several countries, like Austria (at local, state, and federal elections) or Germany (at some sub-national elections) this has already been implemented. The enfranchisement of additional groups of voters intends to inject new life into voting and to strengthen representation. Enfranchising the disenfranchised is normatively desirable, since maximum inclusion is needed to describe a ‘process of decisionmaking as fully democratic’ (Dahl Citation1989, 130). Yet, scholars have warned that such reforms may backfire, since additional extension of the franchise may further reduce turnout rather than enliven participation (Chan and Clayton Citation2006; Franklin Citation2004; Franklin, Lyons, and Marsh Citation2004). To date, the literature on the effects of these two major contemporary franchise extensions to non-national EU-citizens and 16-year-olds on voter turnout – especially at local elections – is inconclusive, for Germany as much as for the other member states of the EU.

With the present paper we aim to contribute to the state of local electoral research investigating and comparing the effects of both major types of contemporary franchise extensions on turnout at German local council elections, an effect that may also be observed in other European countries. To do so systematically, we distinguish between vertical franchise extension (to younger members of already enfranchised social groups) and horizontal franchise extension (including additional social groups without regard to age). In addition, we contribute to research on the effectiveness of electoral reforms, especially franchise extension, on voter turnout (Burden et al. Citation2014; Eichhorn and Bergh Citation2020), and to the wider literature on turnout at local elections (Rallings and Thrasher Citation2005). Finally, the analysis contributes to current reform debates on extending the vote at local and regional elections to younger citizens as well as to non-EU non-nationals. As all these reforms are intended to enhance the legitimacy of the political system, they form part of a wider area of institutional changes that also include reforms with a mixed record of success, like the introduction of direct elections to the European Parliament or an expansion its powers (Franklin and Hobolt Citation2011).

Due to the federal structure of the German political system, the decline in local election turnout can be analysed comparatively over time (1978–2019) and for 13 states in which the institutional context of local elections differs. Based on aggregate turnout data our results show that the horizontal franchise extension to non-national EU-citizens contributed to local turnout decline, while the vertical extension had no immediate effect on turnout. While this does not strictly support recent findings that these youngest voters might strengthen long-term net increase in turnout (Franklin Citation2020), it weakens arguments against lowering the voting age (Chan and Clayton Citation2006).

The theoretical framework

Voting behaviour at second-order elections

Like other second-order elections, local elections are said to differ from first-order elections in two ways (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980; Reif Citation1984): Firstly, because there is ‘less at stake’, turnout at second-order elections is expected to be lower due to lower mobilisation by parties and the media and low levels of interest on the part of the electorate. Secondly, voting decisions are guided primarily by factors related to the main political arena (party identification, consent or dissent with governing parties and candidates), thereby leading to a higher share of invalid or split votes, to smaller and newer parties gaining more votes, and incumbent national parties winning a smaller share of the vote. At the same time, recent research comparing first- and second-order elections in Germany has found that interest in politics predicts turnout at second-order elections better than at first-order contests (Giebler Citation2014). However, the characterisation of local elections as second-order is contested. Comparing local and European elections in Britain, Heath et al. (Citation1999) argued that national considerations play a lesser part in local compared to European elections. Local elections are marked by higher turnout, more ticket-splitting, and higher reporting to vote on issues related to the local election arena than European elections. Therefore, Heath et al. concluded that local elections in Britain were ‘one and three-quarters order elections’ with local factors playing a remarkable role determining local voting behaviour (Heath et al. Citation1999, 39; similar Rallings and Thrasher Citation2005). For Belgium, Marien, Dassonneville, and Hooghe (Citation2015) showed that local elections are to a far lesser extent second-order than expected. There seems to be a continuum in the degree of second-orderness. To better understand this continuum regarding second-order turnout and voting decisions, further theoretical considerations have to be taken into account (Kjær and Steyvers Citation2019, 409; Gendźwiłł and Steyvers Citation2021). These concern place-bound factors like municipal size (Gendźwiłł and Kjær Citation2021), the local party system’s degree of nationalisation (Kjær and Elklit Citation2010), or the composition of the local electorate. In addition, the second-order character of local turnout and voting behaviour may not only vary between constituencies but also over time. Temporal changes should hold for elections in all constituencies similarly and might depend on changing dates of an election within the national electoral cycle (Vetter Citation2015), amalgamations (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2019), or changes in the local electoral systems including franchise extensions. Although normatively desirable, if franchise extensions to non-national EU citizens according to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, and further extensions of the franchise in some European countries to 16- and 17-year-olds, were mainly responsible for declining local turnout, the effect would not indicate local elections becoming less important to voters, parties and the media, than they were before – thereby not indicating a decline in the quality of local elections and local democracy, but opening up far more differentiated interpretations of the observed trends.

Franchise extensions and turnout decline

Existing explanations of turnout change mainly focus on first-order elections, looking at generational change, changes in mobilising agencies, the increasing number of elected institutions, or institutional reform (for an overview Kostelka and Blais Citationforthcoming, 3–5; Dalton Citation2015; Gray and Caul Citation2000; Blais et al. Citation2004). Among the latter, successive waves of enfranchisement have been identified as potential explanations for the observed decline of voter turnout in major democracies (Kleppner Citation1982; Berlinski and Dewan Citation2011; Franklin Citation2004). Only recently have local elections begun to be considered in this context (Aichholzer and Kritzinger Citation2020).

Vertical franchise extensions have taken place in many European countries in the 1960s and 1970s, when the voting age across Western democracies was lowered from 21 to 18. The literature suggests that younger people are less likely to vote than older ones: they are both less interested in politics and less inclined to conceive of voting as a civic duty (Dalton Citation2015; Wattenberg Citation2002, Citation2016; van der Brug and Kritzinger Citation2012; Wolfinger and Rosenstone Citation1980). Blais and Rubenson (Citation2013) have shown that young voters are less inclined to vote because their generation is less prone to construe voting as a moral duty and is more sceptical about politicians’ responsiveness to their concerns: even after controls for life cycle effects, the most recent generation has a weaker sense of duty and external political efficacy and is more likely to abstain. Franklin (Citation2004) and Franklin, Lyons, and Marsh (Citation2004) identified the 1970s wave of franchise extension as a major contributor to decline in turnout. Applying these insights to local elections, we might expect recent reforms enfranchising 16- to 17-year-olds at local elections to have a negative effect on turnout.

However, the evidence is far from clear cut. Several studies have been carried out on the Austrian case, where the voting age has been lowered to 16 for all elections. Wagner, Johann, and Kritzinger (Citation2012) have shown that Austrian citizens under 18 have both the ability and the motivation to participate effectively in an election. Aichholzer and Kritzinger (Citation2020; similar Zeglovits and Aichholzer Citation2014) have shown for Austrian local, state, and federal elections that 16- to 17-year-olds turn out in higher proportions than 18- to 20-year-olds. Analysing voting behaviour and habit formation among 16-year-old voters at Austrian federal elections, Bronner and Ifkovits (Citation2019) have found that eligible 16-year-olds are more likely to vote in future elections. Similar patterns have been reported for a major referendum in Scotland and for several German state and municipal elections (Electoral Commission Citation2014, 64; Leininger and Faas Citation2020). Finally, analysing the enfranchisement of 16- and 17-year-olds in South America and Austria, Franklin (Citation2020) has found that these reforms have led to a long-term net increase in turnout that is mainly due to the increased participation of the youngest cohort of voters. Indeed, proponents of lowering the voting age argue that enfranchisement at the age of 18 is actually too late within a person’s lifecycle, when first-time voters already ‘leave the nest’ (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2012) and with it the social support structures and normative environment conducive to electoral participation. Given these arguments and the recent evidence in their support, we do not expect the lowering of the voting age to 16 to lead to a further decline in turnout. On the contrary, owing to the supportive networks and group socialisation provided by families and friends, franchise extensions to 16 to 18-year-olds might even strengthen aggregate local turnout.

H1: The first local council election for which the franchise was extended to 16- and 17-year-olds is marked by a positive relative change in local voter turnout.

The record of contemporary horizontal franchise extensions is no clearer. With the enfranchisement of women and ethnic or racial minorities largely completed by the 1970s, remaining group criteria concern non-national residents.Footnote4 With the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, EU member states have agreed to grant the franchise to non-national EU citizens in local elections at their place of residence. The corresponding directive was adopted by the EU Council of Ministers in 1994 and transposed into law by the German states by the end of 1995.Footnote5 As a result of this horizontal extension of the franchise, residents possessing the citizenship of any member state of the EU are eligible to vote and to stand as candidates in German local elections across all states. The European Commission’s Report from 2018 states that in that year, non-national EU citizens of voting age made up around 5% of the German voting age population (European Commission Citation2018).Footnote6 Although registration in Germany is automatic for all kinds of election, Diehl and Wüst (Citation2011) have shown that non-national EU-voters hardly exercise their right to vote. Analysing local election data from Berlin, Bremen, Hamburg and Stuttgart, the authors found that, at a maximum of 27%, turnout of EU foreigners is significantly lower than turnout of German citizens.

Even though this group is relevant to Dahl’s criterion of inclusiveness (‘The demos must include all adult members of the association … ’; Dahl Citation1989, 129), it is considerably less well researched than franchise extensions to younger nationals. In fact, the literature is virtually silent on the effect of extending the vote to non-national EU residents due to very limited data (Hutcheson and Russo Citation2021). Thus, our theoretical expectations are guided by historical examples pointing to negative effects of horizontal franchise extensions on turnout in existing democracies.Footnote7 Analysing the effects of female suffrage in the US in the 1920s, Kleppner (Citation1982) argued that the female participation rate was lower than male turnout, for two reasons. Firstly, for many decades the idea of voting as a civic duty was widely considered a specifically male duty. Secondly, upon enfranchisement, female turnout was then further lowered by weak electoral stimuli, whereas male voters, already in the habit of participating, were relatively unimpressed by any decline in the competitiveness or salience of elections. However, unlike women in the early twentieth century, newly enfranchised non-national EU citizens do not per se constitute a group that had hitherto been denied the ability to vote. What distinguishes many of them from their national fellow citizens is a relative lack of psychological engagement with the polity in which they currently reside, and a more limited exposure to the relevant mobilising agents in their social environment that encourage them to take part in politics (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995, 271). These include, above all, family members, friends, or neighbours, as well as political and civil society organisations. Hence, we expect that when non-national EU-voters are added to the local electorates for the first time, this leads to a one-off, yet largely irreversible, drop in overall local turnout:

H2: The first local council election for which the franchise was extended to citizens from other EU-member states is marked by a negative relative change in voter turnout.

Data and measurement

Germany’s local government system is embedded within a multilevel system of government comprising the federal level and the level of the states (Länder). In all states, local government is a two-tier system consisting of districts (Kreise) and municipalities belonging to a district (Kommunen). Large cities, usually those with more than 100,000 inhabitants (kreisfreie Städte) fulfil the functions of both a district and a municipality. Owing to the federal system, each state has its own local government legislation (Gemeindeordnung), which defines the structure and functioning of local government as well as the participatory rights of citizens and residents.

Local council elections in this study refer to district council elections, or to municipal council elections for those large cities that are not part of a district.Footnote8 Within each state, local council elections are held on the same day. However, election days and electoral cycles differ between the states. To protect the independence of local elections from political trends at higher levels of government, there is normally no concurrence of local council elections with federal or state elections. However, there is frequent concurrence of local and European elections: In 1979, two states (Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate) began to hold local council elections on the same day as elections to the European Parliament. Today, local council elections coincide with elections to the European Parliament in nine out of 16 states (eight out of 11 before reunification, see Table A2 in the online appendix).

Since data on local election turnout in Germany is not stored centrally, aggregate data have been collected by contacting the statistical offices in the states. The data used in the following analyses are official turnout figures. Voter registration in all states is automatic. Therefore, the number of eligible voters and the number of registered voters are virtually the same. Turnout is the percentage of eligible voters who cast a vote. We use aggregate turnout data for the 13 territorial states covering the years 1978 to 2019.Footnote9 During these 41 years, 103 local elections have taken place across the 13 states.

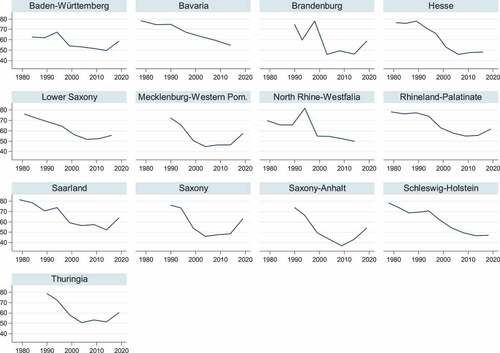

During the 1990s and the early years of the new millennium, turnout at local council elections has declined sharply in all German states (cf. Figure A1 and Table A1 in the supplemental online appendix). In the 1950s, average turnout at local council elections across the Länder was about 77% (Vetter Citation2015). In the late 1980s, local electoral turnout still averaged above 70%. Around 2010, average participation at local elections has fallen by almost 20 percentage points and averaged around 50%. By contrast, turnout at federal elections declined much more moderately, from 78.4% in 1994 to 71.5% in 2013. While the turnout gap between federal and local elections in the period 1991–1994 was only 9.5 percentage points, the gap had increased to 21.6 percentage points in the period 2013–2016.

During the most recent period, local turnout decline seems to have come to a halt and possibly reversed. In May 2019, when eight out of 13 states held local council elections on the same day as elections to the European Parliament (EP), turnout at local council elections was about 10 percentage points higher than at the 2014 elections (see ). This can be attributed, firstly, to the high salience of the 2019 EP elections, which mobilised more German voters to go to the polls than any EP elections after 1989. Secondly, we find rising trends in turnout also for the latest federal and state elections, possibly reflecting increased politicisation in particular with respect to issues like ‘immigration’, ‘climate change’, or the debate about the ‘future of Europe’, as well as the related rise of the far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). The latter has been associated with a rise in turnout, although the empirical support for such an association is mixed (Haußner and Leininger Citation2018). Finally, there are two noteworthy peaks in North Rhine-Westphalia (1994) and Brandenburgia (1998). They reflect the fact that local and federal elections were exceptionally held on the same day.

Figure 1. Trends in local council turnout by state, 1980–2019.

Dependent variable

Different measures have been proposed to gauge turnout change (Gray and Caul Citation2000). Our measure of turnout change is the relative change in turnout between two local elections in a state measured in percent, i.e., the raw change in turnout between two subsequent local elections as percent of the level of turnout at the first of these two elections: Formally measured as ((turnout t1j – turnout t0j)/turnout t0j)*100. For example, in Baden-Württemberg local turnout fell from 67.3% in 1994 to 54.1% in 1999, which is a relative change of −19.6% percent. This way of calculating the dependent variable renders our time-series cross-sectional data stationary and helps to avoid problems associated with correlated error terms. However, this solution to a statistical problem comes at a price: since we use the change in turnout from one election to the next, we can only analyse the immediate effect of a franchise extension. For the same reason, in each state the first election in our sample period is omitted. Additionally, two local elections were exceptionally held simultaneously with federal elections (North Rhine-Westphalia 1994 and Brandenburgia 1998), significantly boosting local turnout (see ). Since these two elections represent a significant deviation from established constitutional practice in the German multi-level system (Dehmel Citation2020, 728), we exclude these as well as the immediately subsequent elections from the analysis.Footnote10 Thus, 86 out of 103 cases remain for regression analysis.

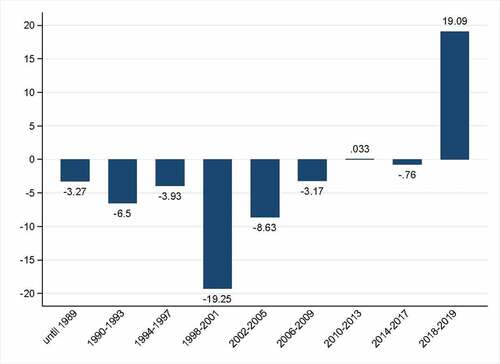

shows the relative changes in voter participation over time by four-year periods (full numerical details are provided in Table A3 in the online appendix). The year 1990 was chosen as the starting point because the East German states have only existed since 1990. The figure illustrates the fluctuations in turnout, which are most pronounced around the turn of the millennium and during the last two years of the period under study.

Main independent variables and controls

To measure horizontal franchise extension, we use a dummy variable that takes on the value of 1 for the first local election following the enfranchisement of non-national EU-citizens. Analogously, vertical franchise extension is a dummy variable indicating an election for which the voting age has been lowered to 16 years for the first time. Besides our two main independent variables we have to consider other factors as controls that might have contributed to short-term changes in local election turnout. Firstly, during the 1990s, the direct elections of mayors has been implemented in 11 out of 13 states,Footnote11 and local government in most German states changed from a more party-oriented towards a more citizen-oriented model of local democracy (Vetter Citation2009). As a result, the role of municipal councils has declined. Local council elections might therefore be perceived as less important, which in turn might depress turnout. Moreover, as the number of elections has thereby increased, at least some voters might abstain due to voter fatigue (Rallings, Thrasher, and Borisyuk Citation2003; Kostelka and Blais Citationforthcoming). We therefore include a dummy variable to indicate the first local council elections held separately from the direct election of the mayor (10 out of 86 elections).

Secondly, holding several elections simultaneously has been found to increase electoral participation, as the cost of voting is lowered for each concurrently held election (Schakel and Dandoy Citation2014; Garmann Citation2016). Leininger, Rudolph, and Zittlau (Citation2018, 523) found that this also holds for concurrent mayoral and European elections, increasing turnout above the level of any of the two second-order elections. In 1979, two German states began holding local council elections on the same day as European elections (cf. Table A1 in the online appendix). Five more states followed in 1994. Today, local council elections are held simultaneously with EP elections in eight out of the 13 states in our data. We therefore include a dummy variable indicating local elections that were held concurrently with EP elections for the first time or that resumed concurrence after a break from this practice.Footnote12

Thirdly, the size of a local polity tends to be negatively related to turnout (Cancela and Geys Citation2016; Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Gendźwiłł and Kjær Citation2021; for more ambivalent findings cf. Denters et al. Citation2014, 234). Especially in East Germaneay the number of municipalities had been reduced since 1990 by more than 65% due to amalgamations following the years after reunification (Wollmann Citation2010). As mergers have been shown to have negative effects on feelings of internal political efficacy and on local turnout, especially when profound changes take place (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2019; Lassen and Serritzlew Citation2011), we also control for major changes in municipal size.Footnote13 Fourth, we control for a potential effect of rising unemployment on turnout by including the change in the unemployment rate in the election year compared to the previous election year in percentage points.

Finally, we include four-year period dummies in the analysis. The periods are defined as shown in . The dummies enable us to control for unobserved factors influencing turnout, such as changes in political interest, declining adherence to social norms, or a change in the electoral system.Footnote14 Most importantly, however, the period dummies capture the trends in our dependent variable and thus prevent the predictors from showing an effect by chance. This reduces the risk of our hypotheses being corroborated on the basis of coincidence, which would be the case, e.g., if the franchise was extended at a time when turnout was falling for whatever other reason. This way we subject our hypotheses to a particularly rigorous test. Summary statistics for all variables used in the multivariate analysis are reported in Table A4 in the online appendix.

Results

To test our hypotheses, we use OLS regression with cluster-corrected (by state) standard errors. We proceed in four steps: Model 1 incorporates only the period dummies. In Model 2 and 3 each of the two franchise extensions are added separately. Model 4 contains both franchise extensions and further control variables (see ). Model 1 confirms the pattern shown in : The relative decline in turnout is particularly pronounced around the turn of the millennium, and this trend continues, albeit to a lesser extent, until 2005. In 2018 and 2019, the downward trend is stopped and even reversed.Footnote15 The period dummies alone account for 71% of the variance in the dependent variable, which raises the bar for additional predictors to exert significant effects, making this a hard test for our hypotheses.

Model 2 contains an indicator for the vertical franchise extension to 16- and 17-year-olds. The coefficient is negative but not statistically different from zero. Thus, the estimates provide no support for our first hypothesis (H1). In Model 3 we add the indicator for the first election in which EU citizens were allowed to participate. This franchise extension is associated with a statistically significant drop in relative turnout by 4.6%, supporting hypothesis H2. Compared to Model 1, the coefficient for the period 1998 to 2001 is reduced by 3.7 percentage points (from −15.98 to −12.32%). In combination with the unchanged R-squared value, the estimates for model 3 therefore suggest that the extension of the franchise to EU citizens accounts for a good part of the decline in turnout during this period.

Model 4 confirms both our findings concerning the effect of the horizontal franchise extension and our non-finding regarding the vertical franchise extension. In the first local council elections where EU citizens were allowed to participate, the decline in turnout due to this horizontal franchise extension was significant and of non-negligible magnitude. Controlling for a number of institutional changes as well as a host of unobserved influences captured by the period effects, the extension of the franchise to non-national EU citizens is significantly associated with a relative change in turnout of −5.4%. Finally, none of the control variables exerts a significant influence on the relative change in turnout beyond the period effects.

Please insert around here!

Robustness checks

We performed several additional analyses to check the robustness of our results. Firstly, to control for potential differences between East and West Germany, a dummy was included in the final model (see Model 1 in Table A5 in the online appendix). We also control for potential unit effects using a full set of state dummies (see Model 2 in Table A5). This has no effect on our empirical findings. Secondly, we test our model using OLS regression with a lagged dependent variable and panel-corrected standard errors (Beck and Katz Citation1995). In this alternative specification, the effect of the horizontal franchise extension narrowly misses the .05 level of significance (p = 0.053 in Model 3 and p = 0.071 in Model 4, see Table A6 in the online appendix). However, with only 86 cases and a relatively high number of predictors we consider the .10 level of significance to be acceptable. As the number of degrees of freedom is relatively low, we finally test changes in the standard errors when bootstrapping them. The significance of the effect of horizontal franchise extension remains unchanged (see Table A7). Thus, our robustness checks confirm the finding that the franchise extension to non-national EU citizens is associated with a subsequent drop in overall turnout at German local council elections.

Discussion and conclusions

Turnout at local elections in Germany has declined dramatically since the beginning of the 1990s, much more so than turnout at federal elections (Bundestagswahlen). Based on the literature on historical and contemporary franchise extension, we have distinguished horizontal from vertical franchise extensions and argued that these have different effects on voter turnout. Firstly, and adding to the nascent field of local electoral research, our results do not support recent findings that vertical franchise extensions to 16- and 17-year-olds strengthen long-term net increase in local turnout (Franklin Citation2020). However, our findings weaken arguments against lowering the voting age to these young voters (Chan and Clayton Citation2006). Secondly, we have found that the horizontal franchise extension to citizens from other EU-countries significantly contributed to local turnout decline.

What do our findings imply for the more general research on the effectiveness of electoral reforms, especially franchise extensions to make (local) representative democracy more inclusive? Political inclusion by participation especially in elections is at the heart of representative democracy (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995, 1). Franchise extensions are intended to increase political inclusion and political representation. Our findings show that franchise extensions do not always meet the expectation that extended rights of participation lead to extended levels of participation and political inclusion. This suggests that franchise extensions may have to be accompanied by mobilisation efforts, especially with respect to those groups targeted by the reforms, to brings about their desired effects. Nevertheless, we only have focussed on short-term effects and therefore cannot predict how lasting the negative effect of horizontal franchise extension is. Given what we know from vertical franchise extensions to 18- to 20-year-olds, the initial voting (non)experience of EU foreigners may have a durable impact on their subsequent turnout (Franklin Citation2004) unless their integration into local politics is strengthened over time. Lower levels of voting among non-national EU citizens may therefore leave a ‘footprint’ of their first election similar to the one identified by Franklin for 18- to 20-year-olds following the reforms of the 1970s. Pending further research, we do not know whether recently enfranchised non-nationals and young age cohorts might well become mobilised by election campaigns emphasising issues such as ‘climate change’, ‘immigration’, ‘nationalization’, and the ‘future of Europe’. The positive period effect of 2018–19, arguably capturing times of re-politicisation, provides merely a vague hint in that regard.

The horizontal enfranchisement following the 1992 Maastricht Treaty also took place in the other EU member states, raising the questions of whether our findings extend beyond the German case. Based on our results we would expect non-negligible turnout effects at least in other countries in which non-national EU-citizens make up a notable part of the electorate, like in Luxemburg, Ireland, Belgium, Austria, or Sweden (Hutcheson and Russo Citation2021, 15). Further research in other EU member states would be valuable to gain more insights into franchise extensions and local turnout decline, including research on how to make local elections more attractive for non-national EU-citizens to participate, especially those with a long-term perspective in the host country.

One caveat remains: Although horizontal franchise extensions to non-national EU citizens explain at least part of the story of local turnout decline, and although many other controls were used, there is still much room left for the potential influence of additional factors. Our aggregate-level analysis is not detailed enough to show who and how many of the newly enfranchised EU-citizens end up using or not using their right to vote and what other factors contributed to the significant decline. Further comparative research from other EU countries and the collection and analysis of local-level data is needed to address this question.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Angelika Vetter

Angelika Vetter is an associate professor at the Institute for Social Sciences at the University of Stuttgart, Germany. Her research focuses on local government studies, especially local elections and democratic innovations. She has published in journals including Local Government Studies, German Politics, International Journal of Public Opinion Research and Politische Vierteljahresschrift. She is currently working on unequal participation and direct democracy.

Achim Hildebrandt

Achim Hildebrandt is a senior researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences, University of Stuttgart, Germany. His research focuses on comparative public policy, public opinion about policies and federalism. Recent work has appeared in the International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Political Research Quarterly and European Journal of Public Policy.

Patrick Bernhagen

Patrick Bernhagen is Professor of Comparative Politics at the Institute for Social Sciences, University of Stuttgart, Germany. His research focuses on problems of political representation. Recent publications include, with A. Dür and D. Marshall, The political influence of business in the European Union, 2019, UMP; and with C. Haerpfer, R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Democratization, 2nd edn, OUP, 2019.

Notes

1. We refer to average turnout because the timing of local elections varies from state to state and across years. The different elections in the states have been grouped around national election years and averaged according to the periods shown in Table A1 in the online appendix.

2. Exceptions include Switzerland (for women) and the United States (for blacks). Our analysis is confined to franchise extensions within existing democracies, defined as political systems in which at least a majority of adult citizens has the right to vote in elections to the legislative and executive. Thus, enfranchisements such as those of the black South African majority following the end of apartheid fall outside the scope of the argument.

4. We refer to franchise extensions within existing democracies, defined as political systems in which at least a majority of adult citizens has the right to vote in competitive elections to the legislative and executive (Alvarez et al. Citation1996). Hence enfranchisements such as those of the black South African majority following the end of the apartheid regime fall outwith the scope of our analysis.

5. Table A2 in the online appendix lists the years in which non-national EU citizens were allowed to vote in local elections for the first time for each state.

6. The Commission’s report refers to non-national EU citizens aged 15 years and older.

7. Research on the re-enfranchisement of blacks, mainly in the Southern states, by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is less relevant here because blacks had not been formally disenfranchised; their de facto disenfranchisement had been achieved indirectlyby a pernicious cocktail of literacy tests, poll taxes and other bureaucratic restrictions as well as harassment and violence.

8. Baden-Württemberg is the only exception. Here local council elections refer to municipal council elections for cities belonging to a district and those not belonging to a district.

9. Germany consists of 16 states. Three of these (Berlin, Hamburg, and Bremen) are city-states and therefore municipalities and states at the same time. Their districts are sub-municipal units (SMUs) with directly elected councils. However, these SMUs do not have the same legal status as municipalities in the other 13 states. They are more akin to administrative boards (Kersting and Kuhlmann Citation2018, 112). Therefore, we exclude elections in the three city-states from our analysis.

10. The subsequent election was also excluded because the change in voter turnout is also distorted in this election: A sharp increase in turnout at the local election, which was held in parallel to the national election, was followed by a sharp decline in the next local election.

11. In the two remaining states (Bayern and Baden-Württemberg), mayors are directly elected already since the 1950s.

12. In contrast, the two local elections in Brandenburg and North Rhine-Westphalia held concurrently with federal elections were removed from the analysis (see above in the section on the dependent variable). The reason for this decision is the aforementioned break with constitutional routine and the resulting bias induced by these exceptions: At the respective local elections, the relative change in turnout was +27.5% (but −4.0% for all other elections). At the six local elections in our data that were held on the same day as EP elections for the first time, voter turnout fell only slightly less (−1.4%) than at the other elections (−3.4%)Citation2015; more generally Cancela and Geys Citation2016.

13. In 81 of the 86 elections in our dataset, the relative change in municipal size (number of inhabitants) is between −5.4% and +11.7%. However, in five elections in East Germany, the average size of the municipality increased by 42.9 to 340.5% due to amalgamation. We include a dummy variable identifying these five cases.

14. Two elections in our data were held after a reform of the local electoral system (Rhineland-Palatinate 1984 and Hesse 2001).

15. The coefficients have to be interpreted in relation to the reference category (the years between 1978 and 1989): Until 1989, the average relative change in turnout was −3.27% (i.e., constant). Compared to this value the relative change in voter turnout was +22.36% in the last two years of the sample period. Hence the relative change in turnout in the last period was 19.09% (22.36-3.27, see also ).

References

- Aichholzer, J., and S. Kritzinger. 2020. “Voting at 16 in Practice: A Review of the Austrian Case.” In Lowering the Voting Age to 16, edited by J. Eichhorn and J. Bergh, 81–101. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Alvarez, M., J. A. Cheibub, F. Limongi, and P. Przeworski. 1996. “Classifying Political Regimes.” Studies In Comparative International Development 31 (2): 3–36. doi:10.1007/BF02719326.

- Beck, N., and J. N. Katz. 1995. “What to Do (And Not to Do) with Time-series Cross-section Data.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 634–647. doi:10.2307/2082979.

- Berlinski, S., and T. Dewan. 2011. “The Political Consequences of Franchise Extension: Evidence from the Second Reform Act.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 6 (3–4): 329–376. doi:10.1561/100.00011013.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2012. “Leaving the Nest and the Social Act of Voting: Turnout among First-time Voters.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 22 (4): 380–406. doi:10.1080/17457289.2012.721375.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2019. “Voter Turnout and Municipal Amalgamations—evidence from Denmark.” Local Government Studies 45 (5): 697–723. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1563540.

- Blais, A., E. Gidengil, N. Nevitte, and R. Nadeau. 2004. “Where Does Voter Decline Come From?” European Journal of Political Research 43 (2): 221–236. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00152.x.

- Blais, A., and D. Rubenson. 2013. “The Source of Turnout Decline: New Values or New Contexts?” Comparative Political Studies 46 (1): 95–117. doi:10.1177/0010414012453032.

- Bronner, L., and D. Ifkovits. 2019. “Voting at 16: Intended and Unintended Consequences of Austria’s Electoral Reform.” Electoral Studies 61: 102064. (October 2019). doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.102064.

- Burden, B. C., D. T. Canon, K. R. Mayer, and D. P. Moynihan. 2014. “Election Laws, Mobilization, and Turnout: The Unanticipated Consequences of Election Reform.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (1): 95–109. doi:10.1111/ajps.12063.

- Cancela, J., and B. Geys. 2016. “Explaining Voter Turnout: A Meta-analysis of National and Subnational Elections.” Electoral Studies 42 (June): 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005.

- Chan, T. W., and M. Clayton. 2006. “Should the Voting Age Be Lowered to Sixteen? Normative and Empirical Considerations.” Political Studies 54 (3): 533–558. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00620.x.

- Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, R. J. 2015. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Thousand Oaks: CQ Press.

- Dehmel, N. 2020. Wege aus dem Wahlrechtsdilemma. Eine komparative Analyse ausgewählter Reformen für das deutsche Wahlsystem. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Denters, B., M. Goldsmith, A. Ladner, P. E. Mouritzen, and L. E. Rose. 2014. Size and Local Democracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Diehl, C., and A. M. Wüst. 2011. “„Germany.” In The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities: Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies., edited by K. Bird, T. Saalfeld, and A. M. Wüst, 48–50. London: Routledge.

- Eichhorn, J., and J. Bergh, Eds. 2020. Lowering the Voting Age to 16. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Electoral Commission. 2014. “Scottish independence referendum. Report on the referendum held on 18 September 2014. ELC/2014/0 2.” http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/Scottish-independence-referendum-report.pdf

- European Commission. 2018. “Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Application of Directive 94/80/EC on the Right to Vote and to Stand as a Candidate in Municipal Elections (COM(2018) 44 Final)”. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2018/EN/COM-2018-44-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF

- Franklin, M. N. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Franklin, M. N. 2020. “Consequences of Lowering the Voting Age to 16: Lessons from Comparative Research.” In Lowering the Voting Age to 16, edited by J. Eichhorn and J. Bergh, 13–41. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Franklin, M. N., and S. B. Hobolt. 2011. “The Legacy of Lethargy: How Elections to the European Parliament Depress Turnout.” Electoral Studies 30 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.019.

- Franklin, M. N., P. Lyons, and M. Marsh. 2004. “Generational Basis of Turnout Decline in Established Democracies.” Acta Politica 39 (2): 115–151. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500060.

- Garmann, S. 2016. “Concurrent Elections and Turnout: Causal Estimates from a German Quasi-experiment.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 126: 167–178. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2016.03.013.

- Gendźwiłł, A., and U. Kjær. 2021. “Mind the Gap, Please! Pinpointing the Influence of Municipcal Size on Local Electoral Participation.” Local Government Studies 47 (1): 11–30. doi:10.1080/03003930.2020.1777107.

- Gendźwiłł, A., and K. Steyvers. 2021. “Guest Editors’ Introduction: Comparing Local Elections and Voting in Europe: Lower Rank, Different Kind … or Missing Link?” Local Government Studies 47 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/03003930.2020.1825387.

- Giebler, H. 2014. “Contextualizing Turnout and Party Choice: Electoral Behaviour on Different Political Levels.” In Voters on the Move or on the Run?, edited by B. Weßels, H. Rattinger, S. Roßteutscher, and R. Schmitt-Beck, 115–138. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Górecki, M. A., and A. Gendźwiłł. 2021. “Polity Size and Voter Turnout Revisited: Micro-level Evidence from 14 Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Local Government Studies 47 (1): 31–53. doi:10.1080/03003930.2020.1787165.

- Gray, M., and M. Caul. 2000. “Declining Voter Turnout in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 1950 to 1997 - the Effects of Declining Group Mobilization.” Comparative Political Studies 33 (9): 1091–1122. doi:10.1177/0010414000033009001.

- Haußner, S., and A. Leininger. 2018. “„Die Erfolge der AfD und die Wahlbeteiligung: Gibt es einen Zusammenhang?” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 49 (1): 69–90. doi:10.5771/0340-1758-2018-1-69.

- Heath, A., I. McLean, B. Taylor, and J. Curtice. 1999. “Between First and Second Order: A Comparison of Voting Behaviour in European and Local Elections in Britain.” European Journal of Political Research 35 (3): 389–414. doi:10.1111/ejpr.1999.35.issue-3.

- Hutcheson, D. S., and L. Russo. 2021. “The Electoral Participation of Mobile European Union Citizens in European Parliament and Municipal Elections.” San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute. RSCAS/GLOBALCIT-PP 2021/2 (April 2021)

- Kersting, N., and S. Kuhlmann. 2018. “Sub-municipal Units in Germany: Municipal and Metropolitan Districts.” In Sub-Municipal Governance in Europe. Decentralization beyond the Municipal Tier, edited by N.-K. Hlepas, N. Kersting, S. Kuhlmann, P. Swianiewicz, and F. Teles, 93–118. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kjær, U., and J. Elklit. 2010. “Local Party System Nationalisation: Does Municipal Size Matter?” Local Government Studies 36 (3): 425–444. doi:10.1080/03003931003730451.

- Kjær, U., and K. Steyvers. 2019. “Second Thoughts on Second-Order? Towards a Second-Tier Model of Local Elections and Voting.” In The Routledge Handbook of International Local Government, edited by R. Kerley, P. Dunning, and J. Liddle, 405–417. London: Routledge.

- Kleppner, P. 1982. “Were Women to Blame? Female Suffrage and Voter Turnout.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 12 (4): 621–643. doi:10.2307/203548.

- Kostelka, F., and A. Blais. forthcoming. “The Generational and Institutional Sources of the Global Decline in Voter Turnout.” World Politics. Kostelka_Blais_Manuscript.pdf (essex.ac.uk)

- Lassen, D. D., and S. Serritzlew. 2011. “Jurisdiction Size and Local Democracy: Evidence on Internal Political Efficacy from Large-Scale Municipal Reform.” American Political Science Review 105 (2): 238–258. doi:10.1017/S000305541100013X.

- Leininger, A., and T. Faas. 2020. “Votes at 16 in Germany: Examining Subnational Variation.” In Lowering the Voting Age to 16, edited by J. Eichhorn and J. Bergh, 143–166. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Leininger, A., L. Rudolph, and S. Zittlau. 2018. “How to Increase Turnout in Low-Salience Elections: Quasi-Experimental Evidence on the Effect of Concurrent Second-Order Elections on Political Participation.” Political Science Research and Methods 6 (3): 509–526. doi:10.1017/psrm.2016.38.

- Marien, S., R. Dassonneville, and M. Hooghe. 2015. “How Second Order are Local Elections? Voting Motives and Party Preferences in Belgian Municipal Elections.” Local Government Studies 41 (6): 898–916. doi:10.1080/03003930.2015.1048230.

- Marschall, M., P. Shah, and R. Anirudh. 2011. “The Study of Local Elections: A Looking Glass into the Future.” PS: Political Science and Politics 44 (1): 97–100. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235476.003.0025.

- Rallings, C., and M. Thrasher. 2005. “Not All ‘Second-order’ Contests are the Same: Turnout and Party Choice at the Concurrent 2004 Local and European Parliament Elections in England.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7 (4): 584–597. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2005.00207.x.

- Rallings, C., M. Thrasher, and G. Borisyuk. 2003. “Seasonal Factors, Voter Fatigue and the Costs of Voting.” Electoral Studies 22 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(01)00047-6.

- Reif, K. 1984. “National Electoral Cycles and European Elections 1979 and 1984.” Electoral Studies 3 (3): 244–255. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x.

- Reif, K., and H. Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections. A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Results.” European Journal of Political Research 8 (1): 3–44. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x.

- Schakel, A. H., and R. Dandoy. 2014. “„electoral Cycles and Turnout in Multilevel Electoral Systems”.” West European Politics 37 (3): 605–623. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.895526.

- van der Brug, W., and S. Kritzinger. 2012. “Generational Differences in Electoral Behaviour.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 245–249. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2011.11.005.

- van der Kolk, H. 2019. “„Lokale Wahlbeteiligung in Europa: Befunde, Veränderungen und Erklärungen.” In Kommunalwahlen, Beteiligung und die Legitimation lokaler Demokratie, edited by A. Vetter and V. Haug, 26–41. Wiesbaden: Kommunal- und Schul-Verlag.

- Verba, S., K. L. Schlozman, and H. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality. Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Vetter, A. 2009. “Citizens versus Parties. Explaining Institutional Change in German Local Government 1989-2008.” Local Government Studies 35 (1): 125–142. doi:10.1080/03003930802574524.

- Vetter, A. 2015. “Just a Matter of Timing? Local Electoral Turnout in Germany in the Context of National and European Parliamentary Elections.” German Politics 24 ((1)): 67–84. doi:10.1080/09644008.2014.984693.

- Wagner, M., D. Johann, and S. Kritzinger. 2012. “Voting at 16: Turnout and the Quality of Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007.

- Wattenberg, M. P. 2002. Where Have All the Voters Gone? Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Wattenberg, M. P. 2016. Is Voting for Young People? New York: Routledge.

- Wolfinger, R. E., and S. J. Rosenstone. 1980. Who Votes? New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wollmann, H. 2010. “Territorial Local Level Reforms in the East German Regional States (Lander): Phases, Patterns, and Dynamics.” Local Government Studies 36 (2): 251–270. doi:10.1080/03003930903560612.

- Wood, C. 2002. “Voter Turnout in City Elections.” Urban Affairs Review 38 (2): 209–231. doi:10.1177/107808702237659.

- Zeglovits, E., and J. Aichholzer. 2014. “Are People More Inclined to Vote at 16 than at 18? Evidence for the First-time Voting Boost among 16-to 25-year-olds in Austria.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 24 (3): 351–361. doi:10.1080/17457289.2013.872652.