?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The focus of this study is the political trust implications of territorial reforms, approaches to territorial reform, and the effects of the mobilisation of political-territorial collective identities. We focus on the political trust effects of political-territorial mobilisation grounded on territorial reforms, and of voluntary and forced structural reforms. The case examined is that of Norway, a country characterised by high levels of trust before a recent county reform. Utilising four survey waves from 2013 to 2019, we measure trust in national politicians both pre- and post-reform, giving us a quasi-experimental design. The findings indicate that political trust was not affected by whether the reform was forced on counties or they accepted it voluntarily. However, political trust was negatively affected by forced structural reforms in combination with regionalism, i.e., mobilisation of political-territorial collective identities. This finding provides new insight about how territorial reforms may affect political trust.

Introduction

The focal point of this paper is the trust implications of territorial reforms. As territorial reforms affect cultural, economic, and political interests, they are the most radical and contested measures in the reorganisation of local units (Ebinger, Kuhlmann, and Bogumil Citation2019). We are interested in how territorial reforms could have implications on political trust, as it is a prerequisite for a well-functioning society. Here, we define political trust as the public sentiment about the government and its political representatives (Norris Citation2011).

Peripheral political mobilisation against central political institutions is emerging as a new trend in many European countries, albeit with different political expressions (Ford and Jennings Citation2020; Jennings and Stoker Citation2017; Lee, Morris, and Kemeny Citation2018; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). The tension between central authorities and regions within a country is a well-known challenge, and political-territorial collective identities have been a focus of attention for political scholars (Keating Citation1998; Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967). The continuing presence of regionalism, understood as political-cultural processes in which a collectivity with a sense of territorial belonging takes action, or an elite mobilises and organises the cultural, economic, and political interests of a territory (Brunn Citation1995; Caciagli Citation2003; Nevola Citation2011), reveals the incompleteness of national integration and suggests regional lack of trust in the central political institutions.

Political-administrative regions within countries are constructions that can have been developed over a long time, more or less in accordance with a distinct culture and historic roots. They may also be comparatively new territorial administrative units designed locally or by the central government, but they are, like other bodies, likely to institutionalise their own practices, norms, interests, and become a political-territorial collective over time. The effects of territorial reforms on community identity have been widely studied in the literature, which concludes that structural reforms lead to social distrust and declining community identity, and negatively affects social cohesion, political, and social participation (Dahl and Tufte Citation1973; Ebinger, Kuhlmann, and Bogumil Citation2019; Nie, Verba, and Petrocik Citation2013; Putnam Citation2001). Moreover, a few empirical studies find a negative relationship between structural reforms and political trust (e.g., Denters Citation2002; Hansen Citation2012). The trust effects of political-territorial regionalism, manifesting in the form of mobilisation grounded on territorial reforms, however, appear unstudied, and the present article aims to contribute to filling this gap in the literature. Broader literature reviews on municipal amalgamations and their effects show that there is a dearth of research on the relationship between amalgamations and trust (Tavares Citation2018). More specifically, this article deals with relatively recently created regional (county) democratic units (around 50 years old), and different reform approaches: structural reforms requested by the central government but deemed ‘voluntary’ (voluntary reforms), and structural reforms designed and enforced by central government (enforced reforms).

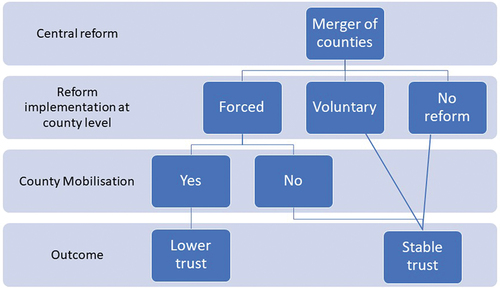

First, we studied whether the reform was voluntary or enforced in relation to the effect on political trust. We test the hypothesis that political trust is linked to reform approaches, and that enforced reforms are accompanied by resistance (as suggested by Steiner, Kaiser, and Eythórsson (Citation2016)), and consequently, declining political trust. Second, we suggest that regionalism, which manifests in the form of mobilisation on the grounds of political-territorial collective identities, is likely to lead to declining political trust in the affected territory. Understanding regionalism due to territorial reforms and its influence on political trust adds new knowledge to the literature on territorial reforms, on community identity and to the literature on trust.

The interplay between territorial reforms, regionalism, and political trust is clearly of general European interest, but here we narrow the focus to a study of county mergers in Norway. Norway was chosen because it has recently experienced reform of its regions with both ‘voluntary’ and enforced county structural reforms. The context is harmonious: Norway, like the other Scandinavian countries, is a well-functioning unitary state, devolving the same sets of powers and discretions to all its county units, with top scores in international rankings on the best country to live in, and top scores on trust in politicians (Dalton Citation2005). Hence, Norway appears to be a rich and harmonious country. However, Norway is a vast territory and around 50 years ago was known for having regions with different political-territorial collective identities (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967). In Norway, we find the most distinct peripheral area, the most recent reforms, and the longest traditions and broad political acceptance of policies that preserve a dispersed settlement, especially in the north (Stein Citation2019).

Our study focuses on the latest structural reforms in Norway. In 2017, the national government implemented a series of local government boundary changes that affected 15 out of the 19 Norwegian counties. To explore this, we use a methodological framework composed of a quasi-experiment with survey data. By utilising four survey waves (DiFi) conducted from 2013 to 2019 with 33,000 respondents, we can measure trust in national politicians both pre- and post-merger. Based on these data, we can observe how the process, that is, the enforced changes, affected levels of trust in the members of parliament (MPs), with the unaffected counties and the counties that accepted the reforms voluntarily serving as a control group. Within the treatment group, we make a distinction between counties that experienced forced mergers with weak mobilisation and forced mergers with strong mobilisation. The findings suggest that the process significantly lowered the level of trust in those counties where mobilisation was high.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we present a broad conceptual framework of political trust and link this to county mergers, followed by a brief presentation of county mergers in Norway. Second, we give details of data collection and the methods applied before presenting and discussing the main results. Finally, we discuss the implications for policymakers and make recommendations.

Perspectives on trust

Trust is a debated concept with competing and complementary explanations of its origin. The cultural perspective argues that trust is embedded in the links and networks between people in the community; that is, trust in political institutions is rooted in cultural norms and communicated through early socialisation (Almond and Verba Citation2015; Inglehart Citation1997; Mishler and Rose Citation2001; Putnam Citation2001). The institutional perspective, on the other hand, argues that trust originates as an outcome of successful policies and that it is a consequence of institutional performance. Institutions that perform well generate trust; low performing institutions generate scepticism and distrust (Dalton Citation2005; Hetherington Citation1998; North Citation1990; Rothstein Citation2011; Van Ryzin Citation2007). Hence, from an institutional performance perspective, political trust can be enhanced by providing good services as a positive evaluation of services spills over to a positive sentiment about the government and its political representatives. Moreover, trust is discussed in relation to democracy and good democratic procedures and standards (Dahl Citation1989; Held Citation1991; Newton and Norris Citation2000) and in some elaborations of Easton’s system support theory (Easton Citation1975). The general idea of political trust is also discussed in relation to national identity in the system building tradition (Bartolini Citation2005; Berg and Hjerm Citation2010; Rokkan and Urwin Citation1983; Stein, Buck, and Bjørnå Citation2021), and this approach serves as the point of departure for our understanding of the relationship between territorial reforms, regionalism, and trust.

Rokkan’s most important contribution to political analysis was the addition of an independent territorial dimension to politics: the centre periphery axis linking the institutional architecture of a nation-state to its territorial structure, that is, it’s given political and spatial characteristics (Rokkan and Urwin Citation1983). Moreover, differing historiographies linked to the process of nation building may create territorially different political interests, and any collective distinction may serve as an underpinning for political mobilisation (Sartori Citation2005) i.e., regionalism. Initially, regionalism seemed to be the ideology of the periphery: marginalised backward regions exploited by the ‘centre’ (Nevola Citation2011), an ideology that is well illustrated today in the works of Jennings (Ford and Jennings Citation2020; Jennings and Stoker Citation2017; McKay, Jennings, and Stoker Citation2021). They focus on the divide between citizens residing in locations strongly connected to global growth and those in locations that are not and find this to be a divide that exists between those from densely populated urban centres with an emerging knowledge economy and people who live in suburban communities, coastal areas, and post-industrial towns (Jennings and Stoker Citation2017, 4–5). The latter group has different values and feels ‘left behind’ in political visions and strategies; they protest and are resentful of the political establishment.

The general idea of the ‘left behind’ is also reflected in Cramer’s (Citation2016) concept of ‘rural consciousness’. Rural consciousness includes a sense that decision makers routinely ignore rural places and fail to give rural communities their fair share of resources or a sense of relative deprivation, and a belief that rural citizens are fundamentally different from urbanites in terms of lifestyles, values, and work ethic. However, regionalism, over the years, has also been understood as an ideology of the richest regions in countries (such as Catalonia). Hence, regionalism is found both in rich and in marginalised regions and manifests in the form of mobilisation and movements based on territorial interests and identity that advance cultural, historical, political, and economic claims (Nevola Citation2011) and are built on a deep resentment and distrust of central government and its political representatives. It has even been suggested that such bitterness and political distrust are linked to distance from the centre: that as a general rule, greater distance from the centre has a negative effect on trust in politicians (Stein, Buck, and Bjørnå Citation2021). Territorial identities are powerful sources of discontent, and in extreme cases, such movements can claim not only cultural and administrative recognition, but also political autonomy.

Territorial reforms, identities, and reform approaches

An optimal jurisdiction size is a cornerstone of government design and has been on the reform agenda in many European countries for decades. Structural reforms have several motivations, the main one being that mergers can create economies of scale and reduce the public cost of administration and bureaucracy. A second motivation is that structural and functional changes in the population pattern can require a new structure (Storper Citation2014). A third issue that often arises in sparsely-populated countries such as Norway is the need for larger units to have the competence and knowledge required to deliver sufficient quality of government (Boyne Citation1995).Footnote1 Hence, the most important drivers for territorial reforms are the objective of achieving improved local finance and human resources, improved quality and quantity of public services, exactness in legal decisions, and improvement for local autonomy and local democracy. These are all crucial characteristics of local government performance (Steiner, Kaiser, and Eythórsson Citation2016). Consequently, a structural reform, if successfully based on these motivations, would lead to increased trust from the institutional performance perspective.

The literature on territorial amalgamation reforms is vast and can mainly be divided into three focus areas. First, there is the research on the impact of territorial reforms on local democracy and elections. In Denmark, there is some evidence that the increase in municipal jurisdiction size has led to positive effects on voter turnout (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2019); however, it has led to decreased voter turnout in other countries (Lapointe, Saarimaa, and Tukiainen Citation2018; Koch and Rochat Citation2017; Blesse and Roesel Citation2019). Some researchers have found that amalgamations have detrimental effects on local democracy because of the reduction in internal political efficacy, that is, individual citizens’ beliefs about their competence related to understanding and participating in politics (e.g., Lassen and Serritzlew Citation2011; De Ceuninck et al. Citation2010).

Second, the desired economic and administrative effects of amalgamation reforms are also contested. Some researchers argue that quasi-experimental studies which offer a causal interpretation do not show that mergers reduce total expenditures, and that potential savings in administrative costs, for example, can be offset by opposite effects for other domains (Blom-Hansen, Morton, and Serritzlew Citation2015). On the other hand, there is a body of literature substantiating the existence of economies of scale in most municipal services and showing that expenses can be reduced through economies of scale (e.g., Blesse and Baskaran Citation2016; Reingewertz Citation2012). In a more recent literature review, Gendźwiłł, Kurniewicz, and Swianiewicz (Citation2021) conclude that saving on administrative spending is perhaps the only clearly confirmed gain of territorial amalgamation reforms. According to them, this finding should re-direct the attention of researchers and policymakers to the varying institutional contexts, territorial organisation prior to the reform, strength of local identities, and political agency of the reforms’ proponents and opponents, as important moderating variables.

Third, the effects of territorial reforms on identity have been widely studied in the literature, which implies that structural reforms tend to lead to social distrust and a decline in community identity (Dahl Citation1989; Ebinger, Kuhlmann, and Bogumil Citation2019; Nie, Verba, and Petrocik Citation2013; Putnam Citation2001). Existing communities are part of people’s identities, understanding the term ‘identities’ as referring to a feeling of similarity and solidarity (Capello Citation2018). Political-territorial collective identities, then, have common and shared values and a solidarity that rests on feelings of attachment and anchorage to the local area. Sources of similarity are identified in history, tradition, culture, and language, which together participate in the creation of borders with others, and have the potential to serve as grounds for mobilisation (Keating Citation2008; Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Rokkan and Urwin Citation1983; Sartori Citation2005). Structural reforms destroy the symbolism of being a recognised community (Denters et al. Citation2014) and consequently are likely to lead to decreased trust in the government and its political representatives within the framework of the community identity perspective, especially if areas with clear political-territorial collective identities are affected. At the very least, it is likely to take time before residents will accept the newly formed entity as a community rather than just an administrative unit (Allers et al. Citation2021).

However, the trust effects of a territorial reform and whether the reform sparks repercussions in the form of regionalism are likely related to the reform approach. Bottom-up reforms can emerge because residents and their politicians find it context-appropriate or where incentives, financial or otherwise, are offered. A bottom-up approach, where territorial reform is introduced incrementally, is likely to experience low levels of resistance (Kaiser Citation2014; Steiner, Kaiser, and Eythórsson Citation2016), and is less likely to lead to regionalism and diminished political trust. There may also be a range of middle-ground approaches, initially based on requests from the central government, but where it may be up to territorial units to ‘find their partner’ themselves. Such approaches may or may not be accompanied by incentives. In these cases, it may be difficult to define how ‘voluntarily’ the amalgamations are. As Swianiewicz (Citation2010) noted, ‘the difference between bottom-up voluntary change and reform implemented in a top-down manner is not very sharp’. Compulsory reforms usually leave some discretion for local governments; voluntary reforms frequently employ powerful incentives. However, in this study, we treat bottom-up and middle ground approaches as ‘voluntary reforms’. However, as per the supporting material, we have conducted robustness checks with mergers that could be categorised as being somewhere in between forced and voluntarily. The results remain consistent with our main argument.

The third category is central government-designed and enforced structural reforms, ‘forced reforms’, which we assume are likely to meet resistance and create conflict between the lower tiers of government and the central government. This is because residents and local politicians do not like top-down decisions on matters that affect them (Steiner, Kaiser, and Eythórsson Citation2016) and because it disturbs established political-territorial collective identities. Forced reforms, we propose, may lead to regional opposition to central politicians, and may even lead to regionalism. Moreover, we propose that regionalism, as manifested by mobilisation on the grounds of political-territorial collective identities, is likely to lead to declining political trust.

Based on these assumptions about the effect of enforced structural reforms, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H1: There is a decline in political trust in regions subject to forced structural reforms compared to regions that have engaged in voluntary structural reforms.

H2: There is a decline in political trust in regions that mobilise on the grounds of political-territorial collective identities, compared to regions without such mobilisation.

Our framework established in H2 can be summarised in

Empirical background: the case of enforced county mergers in Norway

After Norway’s 2013 parliamentary elections, the government changed from a majority-centre-left government to a minority conservative-centre government, dependent on two centrist minor parties. One of the major priorities for the new government was to implement an overhaul of the structures of the Norwegian public sector. The most imminent was the mergers of municipalities (for more about the process and elections see Fitjar Citation2019; Folkestad et al. Citation2019; Stein et al. Citation2020). To get the two minor parties to support the total package of mergers of municipalities, the two largest parties in the government had to agree on reforming the structure of the counties. The main position of the largest government parties was to scrape the county level and split their portfolio (mainly upper secondary school, regional transport, and oral health) between municipalities and the national government. However, the smaller parties wanted to maintain the regional level and they believed that the county portfolio could be expanded with fewer counties.

As shown above, the structural reform of Norwegian municipalities and counties are interlinked, wherein the county amalgamations were an outcome of negotiations between the parties constituting the central government. The Norwegian counties today may be more of an administrative division than a ‘true’ regional level government: they are in charge of relatively few tasks, they have a relatively low score on the Regional Authority Index (a measure of the authority of regional governments developed by Marks, Hooghe, and Schakel (Citation2008)), and they have no formal powers over the municipalities as both counties and municipalities are regulated under the same Act (Lov om kommuner og fylkeskommuner (kommuneloven)).

This process came into effect in June 2017. As shown in the map in , four counties (Oslo, Rogaland, Møre-Romsdal, and Nordland) did not merge. Ten counties merged voluntarily, albeit some more enthusiastically than others.Footnote2 Five counties were subjected to enforced mergers: Østfold, Akershus, and Buskerud into the new county ‘Viken’, and Troms and Finnmark into the new county ‘Troms-Finnmark’. Although there was local opposition in Østfold, Akershus, and Buskerud to their absorption into Viken, the opposition was much stronger in Troms, and even more so in Finnmark. The county administration in Finnmark refused to participate in formal negotiation talks about the merger and passed multiple resolutions in the county parliament opposing the merger. The Finnmark administration also organised a ‘referendum’ on the merger in May 2018. Even though the ‘referendum’ fell far short of meeting the criteria of the Venice Commission’s code on referendums, it showed the level of resistance from political leaders and people with eighty-seven per cent voting against the merger (Finnmark Citation2018). This result is similar to the results found in opinion polls around the same time. The opponents of the territorial reform in Troms and Finnmark also set up two organisations to cooperate in opposing the merger: For Finnmark and For Troms.

The northern region is considered special in the Norwegian context. There is relatively broad academic literature discussing the region’s uniqueness, as it is a sparsely populated territory with vast distances and natural resources, local traditions and adaptions, special communities, challenges, and possibilities (e.g., Brox Citation1966; Jentoft, Nergård, and Røvik Citation2013). Some researchers have urged the preservation of its distinctive artefacts, stigmata, and culture (e.g., Drivenes, Hauan, and Wold Citation1994), while others have found relationships between forging collective identities and successful developmental policies within the region (Bjørnå and Aarsæther Citation2009). In one contribution, the issue of identities within the region has been found to represent exceptionally fertile soil for mobilisation against amalgamation reforms (Bjørnå Citation2013). Previous studies have also shown that the trust in politicians in Norway is lower among the people living furthest away from the capital (Stein et al. Citation2021). Thus, we found grounds for categorising the county as having strong regional mobilisation.

Even though the three counties now constituting Viken opposed the enforced structural reforms the resistance was much less fierce, both among politicians and in the population. The three counties merged to form Viken (Østfold, Akershus, and Buskerud) are all situated in the region around the capital (Oslo) (see ). An opinion poll in June 2017 showed that fifty-one per cent of the respondents were against the creation of Viken as a new unit, while twenty-six per cent were in favour.Footnote3 In contrast to Troms-Finnmark, opposition to Viken did not manage to mobilise political-territorial collective identities. The differences in these experiences make it possible to carry out a quasi-experiment, where some respondents have not experienced a merger, some have experienced a voluntary merger, and some have experienced an enforced merger. Moreover, some respondents experienced a forced merger accompanied by regionalism, while others did not.

Methods and data

Our methodological framework is a quasi-experiment that uses survey data. Finding natural or quasi-experiments has long been a part of programme evaluation in psychology (e.g., Campbell Citation1969; Cook and Campbell Citation1979) and economics (Angrist and Krueger Citation2001; Meyer Citation1995), but such an approach is also emerging in political science (Lassen Citation2005) and in political trust research (e.g., Ares and Hernández Citation2017; Hansen Citation2012). Blom-Hansen, Morton, and Serritzlew (Citation2015) argue that experimental methods are underused in public management research. They introduced five different experimental designs in public management research: lab, survey, field, natural, and quasi-experiments. Quasi-experiments share the characteristic with natural experiments that the intervention comes from the outside. The process not controlled and manipulated by the researcher but is created by nature or the political-administrative system. In contrast to other experiments, however, assignment to experimental and control groups is not randomised in quasi-experiments (Blom-Hansen, Morton, and Serritzlew Citation2015). Therefore, the two groups may differ in terms of their exposure to the experimental intervention (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell Citation2002). Quasi-experimenters thus face the challenge of interpreting whether differences in results are caused by the experimental intervention or by initial differences between the groups. In this study the regions in question may differ in terms of social, political and economic characteristics, and those differences may explain differences in outcome. To address these crucial challenges, we run a placebo test, a propensity score matching (PSM), and a nearest neighbour algorithm to gauge potential endogeneity issues. These are the robustness checks advocated by Gendźwiłł, Kurniewicz, and Swianiewicz (Citation2021) (see Appendix C). Both tests show that there is no systematic difference between the treated and untreated units on a set of socio-economic characteristics (education, income, immigration, age, party preference and marital status). This gives an indication that the non-random randomisation process has been successful. Even though there still can be potential unobserved endogenity issues, quasi-experiments have considerable potential for new studies (Blom-Hansen, Morton, and Serritzlew Citation2015). They are considered to be stronger designs than traditional observational studies because they address endogeneity problems more directly. Further, quasi-experiments, such as natural experiments, render it possible to investigate the effects of phenomena that are difficult for researchers to manipulate. Consequently, if randomisation cannot be sacrificed, many research questions remain unanswered (Blom-Hansen, Morton, and Serritzlew Citation2015). Therefore, we believe that a quasi-experiment is appropriate in this case, even though it comes with a caveat that the treatment is not randomised.

Although there are compelling arguments for combining different indicators when measuring political trust (e.g., Marien and Hooghe Citation2011), there are also important similarities between trust in political actors, liberal democratic institutions, and courts and police (Denters, Gabriel, and Torcal Citation2007). In the current study, we used a single-item variable, trust in politicians, as an indicator of the concept of political trust (other studies with single-item indicators include Hetherington and Rudolph Citation2008; Newton Citation2001; Rudolph and Evans Citation2005;; Van der Meer Citation2010). The respondents were asked to give their answers on a 7-point scale, ranging from −3 to 3, where −3 indicates very low trust and 3 indicates very high trust. Trust in national politicians was measured by the following question: ‘How much or little trust do you have that politicians in Stortinget (the national parliament) are working for citizens’ best interests?’ Our data were obtained from the Norwegian Agency for Public Management and eGovernment citizen surveys (DiFi).

We use a difference-in-difference (DiD) model and test whether counties affected by the merger display a significant change in trust compared with the control group, which is composed of counties unaffected by the merger. As we do not have repeated observations for the same individuals over time, we have chosen to aggregate individual-level data to the county level (individual level models and the number of respondents per county are listed in the Appendix C). Running the analysis on individual-level data would produce biased estimates, because we do not have pre-treatment observations on the individual that received the treatment. We aggregate an average trust indicator per county-year in the DiFi survey, which consists of 33,851 respondents over four survey waves (2013, 2015, 2017, 2019) on 18 counties.Footnote4

Below, we present the results from the different model specifications. First, we used a simple DiD model in which the treatment and time of treatment interact. The model takes the following form:

where Di is the effect of the treatment, that is, forced mergers, and Yi is the outcome, that is, the change in level of trust. is the county fixed effects and

is the time fixed effects. The focus of our interest is the following:

where treati is a treatment group dummy and timei is a dummy for the post-treatment period. To test our hypotheses, we are interested in the DiD estimator .

Results

Before testing our hypotheses, we ensured the validity of our model by using a visual inspection of the parallel trends-assumption, a placebo test, a PSM, and nearest neighbour matching (cf., Abadie Citation2005; Gendźwiłł, Kurniewicz, and Swianiewicz Citation2021). In , we plot the average trust in MPs over time. The field year of each survey wave is denoted on the x-axis. The grey lines represent the local polynomial regression (loess) for each county, and the black lines show the average of the treatment and control groups. To fulfil this assumption, the difference between the treatment and control groups was constant over time in the pre-treatment condition. To our knowledge, there is no statistical test for this assumption, yet a visual inspection can help us ensure that the requirements of the assumption are met. From the plot, we can infer that the pretreatment trends are parallel. The solid line, which represents our control group, is parallel to the two treatment conditions represented by the two dotted lines. Thus, we can conclude that this assumption holds true. To further ensure the validity of our design, we used a placebo treatment test. In this model (see Table F in the Appendix), we administer a placebo treatment in 2015 which is the halfway point in our observations over time, and four years before the actual treatment occurs. The results showed no significant effect of treatment. This, in combination with the visual inspection of , the PSM, and nearest neighbour matching (Appendix C, ), leads us to conclude that our model is internally valid and robust to potential observable endogeneity issues.

After establishing that the model is internally valid, we proceed to the DiD model to test our hypotheses. displays the coefficients from . Our dependent variable is estimated using a simple DiD model with a multivalued treatment indicator. In model 1, we can observe a significant drop in trust starting from the 2017 survey wave to 2019 in all counties. The drop of −.325 points indicates a general decline in trust in national politicians in Norway, albeit from a high initial level. In model 1 we also test our H1 about there being a stronger decline in trust in the counties where territorial reforms were forced. We find that although there is a lower level of trust in the ‘forced’ counties after the reform compared to the other counties, the effect is not significant (β = −.066). In model 2, Troms-Finnmark and Viken (created as the result of forced mergers) are separated based on regional mobilisation as seen in H2, and then compared with the control condition. In , we see that the level of trust in MPs is lower, in general, in the northernmost county (Troms-Finnmark) compared with the control group (−.361 points). In Viken the trust is slightly lower, but only −.163 points, which is only significant at a statistical significance value level of 90%. When analysing the effects of the reform, the DiD estimator, we see that there is a significant drop in trust in national MPs in Troms-Finnmark at −.234 points. For Viken, we observe a positive but insignificant estimator. This tells us that the treatment had an effect in Troms-Finnmark and not in Viken.

Table 1. Regression models.

Discussion

These results indicate that a forced merger does not necessarily lead to a decline in trust in politicians. As seen in , the level of political trust remains the same in nearly all counties, with no significant decline in trust in the merged counties compared to the non-merged counties (with one exception). This suggests that structural reforms can become administrative affairs that are largely accepted. Hence, not all regions subject to territorial reforms have an identity element that leads to decreased trust. This finding adds to the literature on territorial reforms on community identity (Dahl and Tufte Citation1973; Ebinger, Kuhlmann, and Bogumil Citation2019; Nie, Verba, and Petrocik Citation2013; Putnam Citation2001).

We hypothesised a lower level of political trust in regions subject to forced territorial mergers than in regions that have done so voluntarily. The two forced territorial mergers were in Viken and Troms-Finnmark. The models in show no decline in trust in Viken, a finding that contradicts arguments in the structural reform literature (Kaiser Citation2014; Steiner, Kaiser, and Eythórsson Citation2016), where it is asserted that forced mergers are likely to meet with local resistance and result in conflicts between lower tiers and the central government. This is not always the case, and we can reject H1.

H2 posited a lower level of political trust in regions with mobilisation on the grounds of political-territorial collective identities than in regions without such mobilisation. As shown above, voluntarily merged regions and non-merged regions displayed similar trust levels, and there were no significant protests voiced against voluntary mergers. Hence, the instances of forced mergers found in Viken and Troms-Finnmark, where various degrees of protests were evident, becomes particularly interesting in the discussion of H2. In Viken, however, there was no strong regional mobilisation. This could indicate that the tensions between the centre and periphery are less pertinent in regions located around the capital (Oslo). It also indicates that that political-territorial collective identities matter for political trust: The Viken region is not made up of regions with the kind of deep-seated and historically based collective distinctions that could underpin political-territorial collective identities. Consequently, it would be more difficult to mobilise on such grounds against a forced territorial merger. Other grounds for mobilisation, such as a fear of a lower quality of public services because of a merger, would lead to a decline in trust in all the counties affected by the territorial reform. shows the same level of political trust in the merged counties, including Viken, compared to the non-merged counties.

The exception is the northernmost region, Troms-Finnmark. shows a significant decline in trust in politicians in the region affected by a forced merger with strong regional mobilisation. This indicates that mobilisation is a necessary condition for a decline in trust, even after a forced merger, further suggesting that regionalism, not the forced merger itself, is the cause of the decline in trust in politicians. In a classical centre–periphery relationship, a territorial merger is an example of a central authority using force to implement structural changes in the regions. When residents can mobilise the latent structural tension between the centre and periphery (Rokkan and Urwin Citation1983), a decline in trust in national politicians is to be expected. Although this particular experiment does not include the rhetoric used in the mobilisation processes, it has been clearly documented that the two organisations that opposed the Troms-Finnmark territorial reform used the rhetorical power inherited in territorial collective identities,Footnote5 that is, that the organisations mobilised on some form of ‘rural consciousness’ (Cramer Citation2016) and the cultural, economic, and political interests of the territory. Hence, it is likely that mobilisation on the grounds of political-territorial collective identity is relevant in relation to trust in politicians. Hence, this suggests that political territorial identities matter for the acceptance of territorial reforms and that local mobilisation affects political trust. This indicates support for H2.

We found that local resistance and diminishing trust are linked to whether or not regionalism is present, that is, whether a political-cultural process where a collectivity or a group representing a territorial identity mobilises and organises the cultural, economic, and political interests of a territory (see Brunn Citation1995; Caciagli Citation2003; Nevola Citation2011). Although the general levels of political trust declined all over Norway over time, the decline in trust in politicians was steeper in the northernmost region. Hence, the current study’s findings support the Rokkan-inspired hypothesis about the impact of distance: a greater distance from the centre can negatively affect regional citizen trust in politicians (Stein et al. 2019). We suggest that the central state faces a continuous struggle to integrate regions, but that the conception of ‘us’ in the region and ‘the elites’ in the centre may never be removed. Rural areas, particularly the distant periphery, require constant attention and responses. Here, we are particularly likely to find latent conflicts that could be subject to regionalism.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that territorial reforms may have negative consequences for trust in central government politicians. In the current study, the negative consequences of territorial reforms for political trust are linked to organised mobilisation on the grounds of political-territorial collective identities. After the reform, trust in politicians was most diminished in the northernmost region, where there was a strong regional mobilisation based on a historic centre-periphery conflict. This is an explanation for mobilisation in line with basic elements in a Rokkan centre-periphery framework, where political-territorial collective identities can be mobilised and affirm an inherent tension between the centre and regions.

The present study’s design as a quasi-experiment provides a foundation for indicating causation between different types of mergers, regionalism, and trust in politicians, and adds to the literature on county and municipal mergers. For political trust, whether it is a forced merger or not, does not necessarily matter the most. Moreover, establishing that territorial reforms and the way they are introduced may or may not affect trust in politicians; the decisive factor is the presence of political-territorial collective identities that can serve as the focus for mobilisation. This is relevant for policymakers when considering local mergers. This study is also relevant to the literature on political trust, as it adds to our understanding and the growing literature on the relationship between political and territorial collective identities and political trust (McKay, Jennings, and Stoker Citation2021).

As a limitation of this study, we acknowledge that it assesses the trust effects of mergers in a relatively short time period. We were not able to assess whether this would have long-term consequences, the assessment of which would require the conducting of new surveys. Moreover, our analysis is a lesson from a quasi-experiment in Norway for which the treatment groups were not randomly selected. Hence, we could not confirm the external validity of this experiment. However, we find it plausible that similar territorial reforms combined with regionalism may have negative effects on national integration. Policymakers should consider this before implementing territorial reforms. More information on the relationship between territorial reforms and political trust from similar experiments in other countries would be of both interest and use to scholars in the field, and we highly recommend the implementation of further research focusing on the relationship between regionalism and political trust.

Appendix_LGS.docx

Download MS Word (2.7 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Marcus Buck for comments on earlier versions of this paper. They would also like to thank the Governance Research Group at UiT for valuable feedback. Finally, they wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions helped improve and clarify this manuscript

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonas Stein

Jonas Stein is an associate professor of political science at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. His research interests include territorial politics, regional development, political behaviour and elections. He has published in journals such as Regional & Federal Studies, Territory, Politics, Governance, Arctic Review of Law and Politics, and Marine Policy.

Troy Saghaug Broderstad

Troy Saghaug Broderstad is a researcher in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, Norway, who is funded by the Trond Mohn Foundation under the project The Politics of Inequality (grant no. 811309). His current research interests are representation, responsiveness, and legitimacy. He has published in journals such as Democratization and European Union Politics.

Hilde Bjørnå

Hilde Bjørnå is Professor of Political Science at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. Her current research interests are subnational reforms, local development, political-bureaucratic relations, and social media in government. She has published in journals such as Public Performance & Management Review, Territory, Politics, Governance, Public Management Review, and European Urban and Regional Studies.

Notes

1. To this, it should be added that the status of the provincial tier of government in Norway has been highly contested since it was reformed from an assembly of the municipal mayors to a council of directly elected representatives in 1975. Some of the most prominent political parties have called for its abolition ever since.

2. E.g., the merger of Hedmark and Oppland to form Innlandet was formally voluntary, but only after the final bill passed by the national parliament (Stortinget) stated that the counties would be forced to merge if they did not do so voluntarily. For robustness checks, we have run models categorising Innlandet as forced merged (see Appendix C).

4. For Trøndelag, out data does not allow us to separate the respondents living in the old counties, Nord- and Sør-Trøndelag. We therefore treat respondents from these counties (voluntary merger) as one territorial unit. This has no consequence for our analysis as we do not hypothesise a difference in treatment effects between respondents living in the northern and southern region of Trøndelag.

References

- Abadie, A. 2005. “Semiparametric Difference-in-differences Estimators.” The Review of Economic Studies 72 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1111/0034-6527.00321.

- Allers, M., J. de Natris, H. Rienks, and T. de Greef. 2021. “Is Small Beautiful? Transitional and Structural Effects of Municipal Amalgamation on Voter Turnout in Local and National Elections.” Electoral Studies 70: 102284. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102284.

- Almond, G. A., and S. Verba. 2015. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Angrist, J. D., and A. B. Krueger. 2001. “Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 15 (4): 69–85. doi:10.1257/jep.15.4.69.

- Ares, M., and E. Hernández. 2017. “The Corrosive Effect of Corruption on Trust in Politicians: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Research & Politics 4 (2): 2053168017714185. doi:10.1177/2053168017714185.

- Bartolini, S. 2005. Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berg, L., and M. Hjerm. 2010. “National Identity and Political Trust.” Perspectives on European Politics and Society 11 (4): 390–407. doi:10.1080/15705854.2010.524403.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2019. “Voter Turnout and Municipal Amalgamations—evidence from Denmark.” Local Government Studies 45 (5): 697–723. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1563540.

- Bjørnå, H., and N. Aarsæther. 2009. “Combating Depopulation in the Northern Periphery: Local Leadership Strategies in Two Norwegian Municipalities.” Local Government Studies 35 (2): 213–233. doi:10.1080/03003930902742997.

- Bjørnå, H. 2013. “Når kommunestrørrelsen blir en utfordring.” In Hvor går Nord-Norge?-Bind 3 Politiske tidslinjer, edited by S. Jentoft, J. I. Nergård, and K. A. Røvik, 185–196. Stamsund: Orkana akademisk.

- Blesse, S., and F. Roesel. 2019. “Merging County Administrations–cross-national Evidence of Fiscal and Political Effects.” Local Government Studies 45 (5): 611–631. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1501363.

- Blesse, S., and T. Baskaran. 2016. “Do Municipal Mergers Reduce Costs? Evidence from a German Federal State.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 59: 54–74. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2016.04.003.

- Blom-Hansen, J., R. Morton, and S. Serritzlew. 2015. “Experiments in Public Management Research.” International Public Management Journal 18 (2): 151–170. doi:10.1080/10967494.2015.1024904.

- Boyne, G. 1995. “Population Size and Economies of Scale in Local Government.” Policy & Politics 23 (3): 213–222. doi:10.1332/030557395782453446.

- Brox, O. 1966. Hva skjer i Nord-Norge? Oslo: Pax Forl.

- Brunn, G. 1995. “Regionalismus in Europa.” Comparativ 5 (4): 23–39.

- Caciagli, M. 2003. “Devoluzioni, regionalismi, integrazione europea.” Unpublished doctoral diss., University of Bologna.

- Campbell, D. T. 1969. “Reforms as Experiments.” American Psychologist 24 (4): 409. doi:10.1037/h0027982.

- Capello, R. 2018. “Cohesion Policies and the Creation of a European Identity: The Role of Territorial Identity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 489–503. doi:10.1111/jcms.12611.

- Cook, T. D., and D. T. Campbell. 1979. “The Design and Conduct of True Experiments and Quasi-experiments in Field Settings.” In Reproduced in Part in Research in Organizations: Issues and Controversies, edited by R. Mowday, and R. Steers. Santa Monica: Goodyear Publishing Company, 223–326.

- Cramer, K. J. 2016. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dahl, R. A., and E. R. Tufte. 1973. Size and Democracy. Vol. 2. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, R. J. 2005. “The Social Transformation of Trust in Government.” International Review of Sociology 15 (1): 133–154. doi:10.1080/03906700500038819.

- De Ceuninck, K., H. Reynaert, K. Steyvers, and T. Valcke. 2010. “Municipal Amalgamations in the Low Countries: Same Problems, Different Solutions.” Local Government Studies 36 (6): 803–822. doi:10.1080/03003930.2010.522082.

- Denters, B., M. Goldsmith, A. Ladner, P. E. Mouritzen, and L. E. Rose. 2014. Size and Local Democracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Denters, B., O. Gabriel, and M. Torcal. 2007. “Political Confidence in Representative Democracies.” In Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies. A Comparative Analysis, edited by J. W. Van Deth, J. R. Montero, and A. Westholm, 66–87. New York: Routledge.

- Denters, B. 2002. “Size and Political Trust: Evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 20 (6): 793–812. doi:10.1068/c0225.

- Drivenes, E. A., M. Hauan, and H. A. Wold. 1994. Nordnorsk kulturhistorie: Det gjenstridige landet. Vol. 1. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Easton, D. 1975. “A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457. Accessed 9 May 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/193437

- Ebinger, F., S. Kuhlmann, and J. Bogumil. 2019. “Territorial Reforms in Europe: Effects on Administrative Performance and Democratic Participation.” Local Government Studies 45 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1530660.

- Finnmark, F. 2018. “Resultater av folkeavstemning mai 2018.” https://www.ffk.no/_f/p10/i11b1992b-c546-494f-9d23-c53c75060dd0/resultat-folkeavstemning-1.pdf

- Fitjar, R. D. 2019. “Unrequited Metropolitan Mergers: Suburban Rejection of Cities in the Norwegian Municipal Reform.” Territory, Politics, Governance 1–20. doi:10.1080/21622671.2019.1602076.

- Folkestad, B., J. E. Klausen, J. Saglie, and S. B. Segaard. 2019. “When Do Consultative Referendums Improve Democracy? Evidence from Local Referendums in Norway.” International Political Science Review 0192512119881810. doi:10.1177/0192512119881810.

- Ford, R., and W. Jennings. 2020. “The Changing Cleavage Politics of Western Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 23 (1): 295–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957.

- Gendźwiłł, A., A. Kurniewicz, and P. Swianiewicz. 2021. “The Impact of Municipal Territorial Reforms on the Economic Performance of Local Governments. A Systematic Review of Quasi-experimental Studies.” Space and Polity 25 (1): 37–56. doi:10.1080/13562576.2020.1747420.

- Hansen, S. W. 2012. “Polity Size and Local Political Trust: A Quasi‐experiment Using Municipal Mergers in Denmark.” Scandinavian Political Studies 36 (1): 43–66. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2012.00296.x.

- Held, D. 1991. Political Theory Today. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Hetherington, M. J., and T. J. Rudolph. 2008. “Priming, Performance, and the Dynamics of Political Trust.” The Journal of Politics 70 (2): 498–512. doi:10.1017/S0022381608080468.

- Hetherington, M. J. 1998. “The Political Relevance of Political Trust.” American Political Science Review 92 (4): 791–808. doi:10.2307/2586304.

- Inglehart, R. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jennings, W., and G. Stoker. 2017. “Tilting Towards the Cosmopolitan Axis? Political Change in England and the 2017 General Election.” The Political Quarterly 88 (3): 359–369. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12403.

- Jentoft, S., J. I. Nergård, and K. A. Røvik. 2013. Hvor går Nord-Norge?-Bind 3 Politiske tidslinjer. Stamsund: Orkana akademisk.

- Kaiser, C. 2014. “Functioning and Impact of Incentives for Amalgamations in a Federal State: The Swiss Case.” International Journal of Public Administration 37 (10): 625–637. doi:10.1080/01900692.2014.903265.

- Keating, M. 1998. The New Regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial Restructuring and Political Change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Keating, M. 2008. “Thirty Years of Territorial Politics.” West European Politics 31 (1–2): 60–81. doi:10.1080/01402380701833723.

- Koch, P., and P. E. Rochat. 2017. “The Effects of Local Government Consolidation on Turnout: Evidence from a Quasi‐experiment in Switzerland.” Swiss Political Science Review 23 (3): 215–230. doi:10.1111/spsr.12269.

- Lapointe, S., T. Saarimaa, and J. Tukiainen. 2018. “Effects of Municipal Mergers on Voter Turnout.” Local Government Studies 44 (4): 512–530. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1465936.

- Lassen, D. D., and S. Serritzlew. 2011. “Jurisdiction Size and Local Democracy: Evidence on Internal Political Efficacy from Large-scale Municipal Reform.” American Political Science Review 105 (2): 238–258. doi:10.1017/S000305541100013X.

- Lassen, D. D. 2005. “The Effect of Information on Voter Turnout: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00113.x.

- Lee, N., K. Morris, and T. Kemeny. 2018. “Immobility and the Brexit Vote.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 143–163. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx027.

- Lipset, S., and S. Rokkan. 1967. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction. New York: Free Press.

- Marien, S., and M. Hooghe. 2011. “Does Political Trust Matter? An Empirical Investigation into the Relation between Political Trust and Support for Law Compliance.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (2): 267–291. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x.

- Marks, G., L. Hooghe, and A. Schakel. 2008. “Regional Authority in 42 Countries, 1950–2006: A Measure and Five Hypotheses.” Regional and Federal Studies 18 (2/3): 111–181. doi:10.1080/13597560801979464.

- McKay, L., W. Jennings, and G. Stoker. 2021. “Political Trust in the “Places that Don’t Matter”.” Frontiers in Political Science 3 (31). doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.642236.

- Meyer, B. D. 1995. “Natural and Quasi-experiments in Economics.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 13 (2): 151–161. doi:10.1080/07350015.1995.10524589.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. “What are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. doi:10.1177/0010414001034001002.

- Nevola, G. 2011. “Politics, Identity, Territory. The ”Strength” and ”Value” of Nation-state, the Weakness of Regional Challenge.” Unpublished doctoral diss., Università Degli Studio Di Trento.

- Newton, K., and P. Norris. 2000. “Confidence in Public Institutions.” In Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries, edited by S. J. Pharr and R. D. Putnam, 52–73. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Newton, K. 2001. “Trust, Social Capital, Civil Society, and Democracy.” International Political Science Review 22 (2): 201–214. doi:10.1177/0192512101222004.

- Nie, N. H., S. Verba, and J. R. Petrocik. 2013. The Changing American Voter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Norris, P. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. 1990. “A Transaction Cost Theory of Politics.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 2 (4): 355–367. doi:10.1177/0951692890002004001.

- Putnam, R. D. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Reingewertz, Y. 2012. “Do Municipal Amalgamations Work? Evidence from Municipalities in Israel.” Journal of Urban Economics 72 (2–3): 240–251. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2012.06.001.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places that Don’t Matter (And What to Do about It).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024.

- Rokkan, S., and D. W. Urwin. 1983. Economy, Territory, Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries. London: Sage Publications.

- Rothstein, B. 2011. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rudolph, T. J., and J. Evans. 2005. “Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Government Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 660–671. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00148.x.

- Sartori, G. 2005. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. London: ECPR Press.

- Shadish, W. R., T. D. Cook, and D. T. Campbell. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Stein, J., B. Folkestad, J. Aars, and D. A. Christensen. 2020. “The 2019 Local and Regional Elections in Norway: The Periphery Strikes Again.” Regional & Federal Studies 1–13. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1840364.

- Stein, J., M. Buck, and H. Bjørnå. 2021. “The Centre–periphery Dimension and Trust in Politicians: The Case of Norway.” Territory, Politics, Governance 9 (1): 37–55. doi:10.1080/21622671.2019.1624191.

- Stein, J. 2019. “The Striking Similarities between Northern Norway and Northern Sweden.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 10: 79–102. doi:10.23865/arctic.v10.1247.

- Steiner, R., C. Kaiser, and G. T. Eythórsson. 2016. “A Comparative Analysis of Amalgamation Reforms in Selected European Countries.” In Local Public Sector Reforms in Times of Crisis, edited by S. Kuhlmann and G. Bouckaert, 23–42. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Storper, M. 2014. “Governing the Large Metropolis.” Territory, Politics, Governance 2 (2): 115–134. doi:10.1080/21622671.2014.919874.

- Swianiewicz, P. 2010. “If Territorial Fragmentation Is a Problem, Is Amalgamation a Solution? An East European Perspective.” Local Government Studies 36 (2): 183–203. doi:10.1080/03003930903560547.

- Tavares, A. F. 2018. “Municipal Amalgamations and Their Effects: A Literature Review.” Miscellanea Geographica 22 (1): 5–15. doi:10.2478/mgrsd-2018-0005.

- Van der Meer, T. 2010. “In What We Trust? A Multi-level Study into Trust in Parliament as an Evaluation of State Characteristics.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 76 (3): 517–536. doi:10.1177/0020852310372450.

- Van Ryzin, G. G. 2007. “Pieces of a Puzzle: Linking Government Performance, Citizen Satisfaction, and Trust.” Public Performance & Management Review 30 (4): 521–535. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576300403.