ABSTRACT

Since 2010, local authorities in England have faced a dramatic cut in funding from central government, associated with a neoliberal super-austerity seen in many countries. At the same time, these authorities have also been increasingly concerned about the problems associated with private sector delivery of housing and the consequences of their increasing responsibilities for dealing with homelessness. The result has been a resurgence of local authority direct engagement in housing provision. Drawing on extensive survey data, this paper explores the extent of this housing delivery activity, the various means utilised and the motivations for this engagement, which includes activity on a spectrum from more entrepreneurial income generation to more socially focussed actions that align to the ‘New Municipalism’. We conclude that this growing housing provision activity by local authorities has the potential to reduce dependence on central government and could help reinvigorate the local state, albeit with associated risks.

Introduction: English local government and the twin crises of austerity and housingR

Since 2010, there have been two challenging crises closely involving local government in England: the crisis of austerity – impacting local government finances and capacity – and the housing crisis (NAO Citation2018, Citation2019). Both crises can be understood as politically constructed and multi-faceted (Gamble Citation2015). They are also inter-related, not least because they focus on the same scale of the local state but also reflect on central-local relations in England (Rhodes Citation2018).

Austerity for the local state has not been unique to England, with Peck (Citation2012) writing about the devolution of austerity in the US, which he terms ‘austerity urbanism’, whilst Standring and Davies (Citation2020) characterise the decade after the global financial crash as the ‘age of austerity’ in Europe, particularly impacting the local state. However, as with neoliberalism more broadly, the impacts of such austerity will inevitably be varied given the differing contexts into which it is implemented. In the UK, as one of the most centralised states (OECD Citation2020), local government has long been heavily reliant on central government grant funding, generated by national taxation, for a majority of its income, and the allocation of this has involved a redistributive element to account for differing local need. Local councils in England lost 27% of their spending power from 2010 to 2015, with further reductions in their central grants from 2015 to 2020. The tradition of fiscal equalisation between authorities has also been abolished, leading to severe fiscal stress for many councils but particularly for more deprived, urban authorities (Hastings et al. Citation2017; Davies et al. Citation2020).

The policy of austerity for local authorities in England has had a significant role in determining their priorities, programmes and expenditure (Gamble Citation2015; John Citation2014). Austerity policy has been concerned with the specific funding choices (Overmans and Noordegraaf Citation2014; NAO Citation2019) together with the potential for greater central control over priorities where government policy incentivisation has been generated through specific funding regimes and a prescriptive ‘deal culture’ (Lowndes and Gardner Citation2016; Bailey and Wood Citation2017). The pressures on local government services have increased over the last decade both directly through cuts to local authority budgets but also to other areas of public expenditure including for benefits and financial support for the unemployed and disabled (Taylor‐Gooby Citation2012).

The effects of the mantra of the ‘age of austerity’ on local government have been widespread. At the same time, because of the tapered removal of central government grant funding and the absolute reductions in finance available on a guaranteed basis (NAO Citation2018), local authorities have been seeking alternative methods to generate income that are secure, consistent and under their own control rather than at the whim of central government policy. They have also arguably had more opportunity to pursue their own initiatives, while central government has been diverted by Brexit and COVID-19.

Contemporaneous with this period of austerity for local government, we have also seen a what has been termed a ‘housing crisis’ across England. The issues are multi-faceted, involving not just the overall supply of homes delivered, but also issues over the type, location, tenure, affordability, and quality of housing. There has, however, been a particular central government focus on issues of supply, which have tended to be linked to notions of planning controls restricting development (Gallent, Durrant, and Stirling Citation2018) and has resulted in the planning system being directed to the delivery of market housing. Much local authority interest has been related to pressures on meeting the shortfalls in housing needed as a result of this market-oriented policy including the political responses to local antagonism (Matthews, Bramley, and Hastings Citation2015). Access to market housing through incentivised government programmes such as the New Homes Bonus, which provides additional central funds for local authorities based on the amount of new housing delivered in their areas (Dunning et al. Citation2014; Wilson Citation2015) has also been a key factor in the type of housing provided. However, there is a growing gap between this government-generated supply and local housing need.

While the direct provision of housing has long been regarded as a local authority core activity, the removal of powers and funding to provide social housing since 1980 has meant it has become residualised (Jacobs et al. Citation2010; Forrest and Murie Citation2014). However, 48% of the local authorities have maintained a limited role in social housing managing existing but declining stock mainly built before 1980 and eroded by Right to Buy (RTB) council house sales, a policy introduced by the government of Margaret Thatcher allowing council house tenants to purchase their properties at a heavy discount (Morphet and Clifford Citation2020). The rental income from any retained housing stock in a council’s ownership is, by law, kept in a ringfenced account known as the Housing Revenue Account (HRA). For those councils who do not own housing stock, their activity has been reduced to their core functions of providing housing advice and responding to homelessness, relying on other institutional providers, such as housing associations and the private sector to meet local housing needs. These responsibilities were increased through the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, which means that local authorities now have to work with those at risk of homelessness. Local authorities spent £1.15 billion spend on homelessness services during 2015–16, a rise of 22% in real terms since 2010–11, but over the same period had experienced a real-term decline in government funding of 36% (NAO Citation2017).

The HRA is a political rather than accounting construct, restricting local authority borrowing to build social housing and placing all HRA dwellings in the RTB category (Lund Citation2017). Hence, even where local authorities have been active in provision, including using the Government’s restricted terms available for replacement of RTB properties, the core stock of social housing has been reducing (Jones and Murie Citation2008). Instead of focussing on social housing, successive Governments’ policies for the housing market have been largely focused on two components: to expand the volume of housing in the private sector rented and for sale and to maintain political commitments to home ownership for first-time buyers (Somerville Citation2016). The government has also intervened through a range of policies to remove security of tenure for existing local authority housing tenants, to stimulate local authority RTB sales and to make housing association properties subject to RTB, thus removing more dwellings from the social and affordable housing stock.

As we discuss in the next section, a great deal of existing scholarly work on austerity considers the resultant changes in power relationships between central and local government generated by the retrenchment of the local state, including the implications of reductions to service provision. Whilst recognising the importance of examining and discussing such trends, and the very real impacts for local communities, we argue that the response of English local authorities to the housing crisis provides an example of a contrasting picture, whereby, the changing role of the local state in society is not just one of the retreat. This is, in turn, having an effect on longer term central-local power relations. We illustrate this through empirical evidence demonstrating the way there is a return to local authority direct provision of housing, through a variety of means, motivations and methods exemplifying an expanding role and more confident use of powers. Having then considered some of the challenges and barriers that do still exist, we conclude by reflecting on the implications for our understanding of austerity and local government, whether this might be a mechanism for re-asserting the role of local authorities within the state and changing the nature of central-local relations in England.

Super-austerity and the role of the local state

The austerity programme introduced by Chancellor George Osborne in 2010 was a political rather than an economic programme (Gamble Citation2015). The Chancellor used the mantra of austerity to promote a reduction in the size of the state (Skidelsky Citation2015). This accords with a wider neoliberal politics seen internationally, for example Peck (Citation2014, 19–20) describes the ‘renewed ideological offensive against the public sector and the social state’ and the resultant ‘effort to redistribute both the costs of and the responsibility for the [global financial] crisis’.

Peck (Citation2014) also notes that this ideological offensive has involved a cascading of austerity measures to the local level and raising the very real prospect of local state failure in the US and the associated need for crisis management (see also Peck Citation2012). Others suggest that austerity politics in the UK has involved scalecraft (Fraser Citation2010) as a means of shifting blame for decision making (Haughton et al. Citation2016) in a form of ‘scalar dumping’ (Shaw and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2016) from central to local government. Austerity has further served as a central feature of the wider blame-shifting culture between central and local government (Cochrane Citation2016). The result is a fiscal disciplining involving local state retrenchment and restructuring with local authorities cast in the ‘uneasy position of “agents of austerity”, tasked on the one hand with administering unprecedented budget cuts and on the other with catalysing economic growth and coordinating local welfare programmes’ (Penny Citation2017, 1352).

Much of the research on the effects of austerity within local government in this period has focussed on the efficiencies and cuts that have been made in specific services (Lowndes and McCaughie Citation2013) and draws upon the legacy of similar practices that have been in operation since the IMF crisis in 1976. It has also focused on the transfer of services and social responsibility to voluntary and community organisations that have taken on the operation of libraries, food banks and other social support (Clayton, Donovan, and Merchant Citation2016). Indeed, unable to reduce expenditure through the ‘mystical’ powers of increased efficiencies, authorities have instead tended to make widespread spending cuts, including reducing capital expenditure (particularly as they have not been able to support the costs of serving borrowing from their revenue budgets (NAO Citation2016)), and major job losses (Ward et al. Citation2015). A widely shared disposition in local government driven by structural and local strategic constraints has been described as ‘austerian realism’ (Davies et al. Citation2020). This has, however, been disputed with Barnett et al. (Citation2021) suggesting, in ways similar to our own argument, that there may be slightly more agency for local government than the concept of austerity realism suggests.

Debates over how to conceptualise recent trends in local government notwithstanding, there have been examples of services being cut completely, with closures of youth centres, day centres and cutbacks to parks, allotments, libraries and leisure centres (Fitzgerald and Lupton Citation2015). The result is reductions in the range, reach and quality of public services and a smaller local employment base being provided by local authorities directly (Hastings et al. Citation2015). When the impacts of austerity are viewed in aggregate, ‘a picture emerges of an entire social infrastructure being destroyed’ (Crewe Citation2016, 3).

This path to austerity in local government in England is closely associated with Secretary of State 2010–15 Eric Pickles, who firmly held the view that authorities should be generating more funding through their own activities, including using financial balances and assets through income generating activities (Lowndes and Gardner Citation2016). The financial freedoms that allowed local authorities to use their assets in this way were included in new legislation introduced by Secretary Pickles: the Localism Act 2011, which allowed local authorities to create companies, banks and other legal entities singly or with other local authorities or partners. The Localism Act 2011 promotes local government innovation with such activity becoming come to be seen as the only viable mechanism to otherwise relentless fiscal retrenchment under austerity (Davies and Blanco Citation2017; Penny Citation2017).

As Thompson et al. note, ‘municipalities are beginning to experiment with creative responses to these crises, such as taking more interventionist and entrepreneurial roles in developing local economies, generating alternative sources of revenue or financialising existing assets’ (Citation2020, 1171). We are seeing the tentative emergence of an assemblage of different and interwoven new municipalist interventions from the more radical to the more neoliberal, from what Thompson et al. (Citation2020) characterise as ‘grounded entrepreneurial municipalism’ to ‘financialised municipal entrepreneurialism’. Such proactive, generative local statecraft stands in contrast to the more passive, competitive approaches of earlier ‘urban entrepreneurialism’ (which included asset-stripping public land and services) (Lauermann Citation2018) with an emergent range of activities and approaches distinguished by differing economic logics, emphasis, content, scope and social implication (Phelps and Miao Citation2019).

This resurgence in municipalism, driven by a desire to attempt to break with neoliberal austerity-as-doctrine, has been labelled as the ‘new municipalism’ (Standring and Davies Citation2020). As Thompson (Citation2020) argues, however, a more cooperative new municipalism is specifically about a more radical and reformist orientation towards the local state, whereby experimentation seeks to proactively deliver social value.

This brings us back to the recent context for local government in England where pressures on local authorities through the reduction of direct Government funding, dwindling social housing stocks and the effects of austerity on their local population (Kennett et al. Citation2015) has resulted in actions that are attempting meet all three issues in a positive way, challenging the decline narrative (Gardner Citation2017; Christophers Citation2019). This involves experimentation and utilisation of new powers with housing delivery at the centre of these emergent approaches.

There has been some work on the increasing trend for local authorities to establish their own companies to deliver housing (for example, Hackett Citation2017; Beswick and Penny Citation2018). However, there is a lack of work that looks comprehensively at the full extent of local authority activity around housing development. This is an important gap in the literature since (as we will show) this activity has now become widespread, with more than 80% of the councils self-defining as being involved in direct housing delivery (Morphet and Clifford Citation2021). Councils are using multiple means and motivations for delivery. While it was initially linked to attempts to raise income in response to austerity since 2017 there has been an increased focus on meeting housing needs through the provision of locally affordable housing (Morphet and Clifford Citation2021). We now turn to discuss the findings of our research that indicates that local authorities have used a variety of ways to return to direct housing provision, to improve their long-term financial stability and to try to establish greater independence from the central state.

Research methods

We investigated how local authorities in England have responded to austerity with particular focus on housing provision by undertaking three similar research projects in 2016/2017, 2018/2019 and 2021 (Morphet and Clifford Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2021). All waves of the research have involved a mixed method approach. In total, 100% local authorities in England were surveyed directly through an online questionnaire, an invitation to complete this being sent to senior council officers involved in central policy, housing, urban planning and finance, with email addresses obtained from publicly available local government directories. These surveys involved a mixture of closed and open questions, focused on investigating the level of activity within each council in relation to direct delivery of housing, their motivations for being engaged in housing again, the way housing development was being conducted and what kind of housing local authorities were providing. All the questions in the 2017 survey were repeated in the survey administered in 2018 and published in 2019 and in the recent 2021 survey, however some additional questions about joint venture (JV) and land arrangements were added in 2018 (then repeated in 2021).

Two hundred and sixty-eight officers from 197 different local authorities responded to the 2017 survey, 184 officers from 142 authorities responded to the 2018 survey and 282 officers working in 194 different local authorities across England responded to the 2021 survey. At present, there are 343 local authorities in England. In our analysis of each survey, where there were multiple responses from the same authority and a unified response per authority would be useful, we compared the responses, and in the event of disagreement between respondents either going with the majority view or using ‘not sure’ as the response if there was no majority view. For other questions, particularly the open questions on general opinions on challenges and barriers, we have analysed all responses received.

The direct survey has been complemented by a desk survey looking at published online information about local authority strategies and engagement in housing and property development for all 343 authorities. In addition, 35 roundtable discussions were held with planning and housing officers in every region of England and 30 case studies whereby one or two individuals per authority were interviewed (in a semi-structured interview format) as to their experience of direct delivery of housing were undertaken. The case study interviewees were recruited from those volunteering for this in the response to our direct survey. In this paper, we concentrate on our direct survey results since these provide a distinct data set and constraints prevent fully exploring the richness of other data, however these other data sources have informed our understanding of the issues as reported here.

What has motivated local authorities to engage in housing provision again?

Local authority engagement in direct delivery of housing has now become widespread again. In our 2021 survey, 80% of the local authorities reported that they were directly engaged in delivering housing, an increase on the 69% reported in the 2018 survey and the 65% reported in our 2017 survey. This engagement has developed over the last decade for a range of motivations, generally led by one dominant factor in each council, but the research demonstrated that these were supported by a cluster of motives that are related to taking greater control in relation to specific local issues. It is interesting to note, as shows that whilst the importance of meeting housing requirements has remained consistent as the highest rank motivating factor between our surveys, improving the quality of design has become more important over time whilst income generation has become slightly less so (but still features highly). Overall, the range of motivations that we discovered were in four main groups, to which we now turn.

Table 1. Motivating factors for local authorities to engage directly in housing provision, in order of importance according to survey respondents.

Local authority core priorities

The predominant motivation was driven by a fundamental view that local authorities need housing for their citizens and should be providing it as part of their core business. In the absence of policy and support from central government, direct action had to be taken locally. In case study interviews, it was often reported that while market housing might represent societal aspirations, it rarely matches local need, the market not providing homes for social rent, older or disabled people or local key workers. Housing availability has become an increasingly pressing issue locally for many councillors and affordable housing has become a growing priority for local authorities, with 80% identifying it as such in their corporate plans (Morphet and Clifford Citation2021).

There is also concern with the effects of homelessness, which has been exacerbated by central government policies that extended the responsibilities of local authorities for this without adequate resources (NAO Citation2019). The costs of providing accommodation for the homeless have escalated as competition increases in the private rented market and this pressure on supply has been accompanied by landlord behaviour that has resulted in an increase of no-fault evictions for those in work. Much of the housing accommodation available to councils to provide for homeless people is in former local authority stock or in poor quality conversions from offices (Clifford et al. Citation2019). This has led councils such as BCP and Tunbridge Wells to taking direct action by purchasing properties and housing people in their own temporary accommodation. This was reported as helping to reduce payments to third-party landlords, creates an asset, income, and better outcomes for homeless people

A further, and somewhat more controversially, core motivation for local authorities engaging in housing delivery has been as a means to address income lost through austerity and to create a more secure financial future. The provision of housing, across all types of tenure, can offer an income stream in perpetuity, while the assets are retained. Undertaking this kind of housing provision, whether built directly such as Bristol or Wolverhampton, through JVs such as Gateshead or Westminster or purchased directly from housing associations or developers such as Brent, can provide secured income. Local authorities have started to take greater control of their longer-term finances by behaving like patient investors with some buying land with the intention of keeping it for 30 years before considering its development. This ‘profit for purpose’ type approach was a key driver for some authorities and demonstrates the link between the housing and the austerity crises at the local scale.

Place regeneration

The second series of motivations was engagement in regeneration and placemaking whether in housing estates or town centres. In 2021, this has appeared as a major type of council activity, not least as part of post-pandemic recovery plans. While retail anchor tenants falter in town centre regeneration, it now appears that housing, including for affordable rent, is an anchor land use for new regeneration projects.

Local authorities have become increasingly concerned about the quality of completed market homes and the lack of control that they have over the design quality of market housing, which is often seen as poor and not reflective of the local context. As a response, many local authorities consider that by developing their own housing they can demonstrate to the private sector that good design, quality and placemaking can all be achieved within a viable budget and planning policy for developers’ contributions. There was also a role identified in dealing with longstanding problem sites, such as in Nottingham, where a series of measures have addressed long vacant sites that owners have no interest in developing. Developing to ecohomes (low carbon) standards as part of a response to the climate emergency has also become increasingly important, for example, being mentioned as a priority in Exeter and Cambridge.

Planning frustrations

For a number of local authorities, the motivation to directly engage in the provision of housing was based on their frustrations at their lack of influence over the delivery outcomes of the planning system, with its increasing focus on the provision of market housing. This frustration includes the time taken for developers to conclude planning consents, the increasing practice of developers renegotiating development contributions once planning consents have been given, and then the slow process of implementing consented schemes (Letwin Citation2018). Furthermore, in 2020, the LGA estimated that there were over 1 million homes available in unimplemented planning consents (LGA Citation2020). This caused concern in many councils, particularly when it was perceived councillors had taken a political hit for supporting planning applications, which then did not even get built, putting further pressure on the release of other sites in the locality when pursued by developers.

In some local authorities, such as Sefton and East Riding, we found that there was a reduction in interest in any housing development from private developers or housing associations. Instead, development activity was focused on other nearby hotspots such as Liverpool and Hull. There is an increasing view that planning alone is not enough to provide the range and type of housing needed locally, hence a perceived need to take direct action. In Hull, the council is now increasing its own affordable housing delivery as a consequence of the skewed provision created by Help to Buy in its area. It now appears to be widely accepted that sufficient affordable housing cannot be secured simply as a residual of private sector market housing development negotiations and local authorities will need to take other action to deliver housing to meet need. Councils also consider that they have the powers and are increasing their competence and skills base to achieve this.

Social/economic motivations

Finally, there was interest in using the direct provision of housing to support small local businesses whether in construction or architecture. This is where there were clear examples of the direct provision of housing aligning with some of the tenants of ‘new municipalism’ (as discussed in Thompson Citation2020), for example, in Bolsover a JV sees new council (social) housing being built with a locally based small builder as the contractor working directly for the local authority. Some councils were also using social value contracts in relation to housing developmentfor example, to support apprenticeships in Birmingham or to support training of ex-offenders in Stockport.

How have local authorities been providing housing again?

Local authorities have been using a range of institutional forms to provide housing again, ranging from the establishment of local housing companies, which might be companies wholly owned by the council or owned with another partner as a ‘joint venture’, building using the funds in their HRA, building using funds available from their ordinary finances (their ‘general fund’), or working in partnership with a variety of partners such as housing associations. 75% of the authorities with an HRA reported in our 2021 survey that they were using receipts received from RTB sales to develop new social housing, albeit subject to central government-imposed restrictions on how these are used (MHCLG Citation2021).

In our 2021 survey, 55% of the local authorities reported having one or more ‘local housing company’, an increase from the 42% reporting this in our 2018 survey. In terms of the ownership of these companies, from our 2018 survey we saw that 83% of the authorities with a company had a wholly owned housing company and 34% of the authorities with a company had a joint venture housing company (the overlap being those who had both JV and wholly owned companies). In the desk survey of all local authorities undertaken in 2021, we found evidence that 82% of the councils had a company of one type or another that might be related to housing, including those for property ownership. Asked in an open question the purpose of these companies in 2021, a wide range of responses indicated the variety of objectives authorities are trying to achieve including increasing housing delivery locally, pursuing regeneration, building on under-utilised council land, providing market housing to generate income that can be reinvested in social housing, delivering homes to certain design and eco standards, supporting local economies through contractors, and making profit for the council. It was also mentioned in some interviews that as company rather than council owned homes, the RTB would not apply.

Most local authorities reporting a company in the surveys had one company, but some had multiple companies. Councils having a range of companies were using them to meet different specific objectives. For example, South Norfolk had three companies (under the Big Sky Group). Eastleigh Council reported that they had four companies (Aspect – Building Communities, Spurwing Developments, Spurwing Ventures 8 and Pembers LLP). Exeter also reported four companies but noted that three were dormant. Oxford Council reported five companies (Oxford City Housing Ltd, Oxford City Housing (Investment) Ltd, Oxford City Housing (Development) Ltd, Barton Oxford LLP and Barton Park Estate Management Co Ltd). In a new question in our 2021 survey, 15 different authorities reported they did have a company which was now dormant, sold off or closed. The reasons behind this varied from changed political priorities or administrations in authorities to exploring alternative options for housing delivery (which is possible without a company structure).

In reviewing how councils are funding this housing development, we found that some were using their RTB receipts to develop new social housing. For those authorities with wholly owned or JV companies, the most common source of funding was the council drawing on its own resources. The was no expectation of central government support or subsidy for housing provision (albeit this presents real challenges around building sufficient social housing). Councils are making loans to their companies from the general fund, using council buildings and land to secure loans and through building on council owned land. A government organisation called the Public Works Loans Board was a popular source of finance. This range of funding and organisational delivery models seems suggestive to us of local innovation and a desire to explore all means possible to deliver housing, as opposed to local state retrenchment.

Where have local authorities been engaging in direct provision of housing?

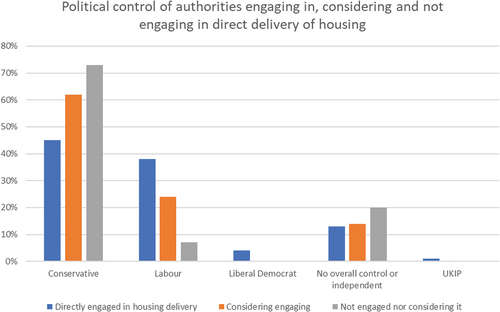

The desire to try to exert greater control over finance, housing and planning through direct delivery of housing is apparent across the whole of England, in all types of local authorities and across all political control. In our 2018 survey, the regional distribution of local authorities within each category of directly engaged in housing delivery shows that authorities in the East of England, London and the South-East are slightly more likely to be engaged in delivery while those in the East Midlands and North West are less so ().

Figure 1. Regional distribution within each category in relation to directly delivering housing (as in 2018).

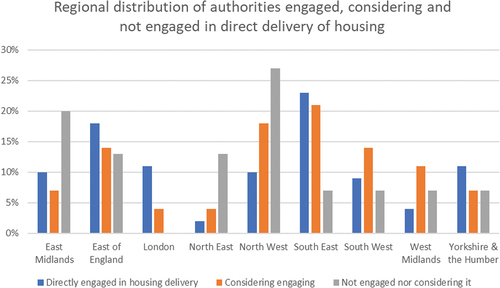

Looking at political control of authorities, we found that Conservative authorities are also slightly less represented than might be expected (). This also reflects the trend with the political control of authorities who have a local housing company. In examining the political control of those with wholly owned as opposed to JV housing companies, no pattern emerged and there were examples of wholly owned and JV companies from authorities similarly to the overall proportion of councils under each political control.

From our 2017 and 2018 surveys, a large urban Labour-controlled authority in the greater South-East with high housing need was more likely to be engaged in direct delivery than a small rural Conservative-controlled authority in the Midlands or North of England. However, over time as activity has spread, we see that authorities of all types, political control and all regions of England are now directly engaged in delivering housing. In Greater London and Greater Manchester, this now includes every local authority.

What types of housing are local authorities building?

In this resurgence, Councils are not just building what we might define as ‘council housing’ – socially rented homes – but across tenures, responding to their various motivations for direct delivery. Many authorities have reported that the quality of private rented sector (PRS) housing is a challenge with much of the recent private build to rent property of poor quality. Tenants need other council support, which has promoted some Councils to build PRS housing such as the 1,250 units reported by Manchester City Council in our 2021 survey. Several local authorities such as Cheltenham and Mendip report using companies to hold stock for temporary accommodation as private landlords are antipathetic to those on benefits. Given the costs to councils of housing homeless people, there is a clear justification for councils to purchase properties to reduce costs and numbers in private accommodation. One council has set up a JV to purchase properties to use as temporary accommodation and Haringey has a Community Interest Company for this purpose.

In the 2018 direct survey, 71% of survey respondents reported that their authority was building or planning to build special needs housing particularly for older people. This compared to 42% in 2017. Other special needs were also being addressed with 37% of councils building housing for people with mental health needs and 60% people with physical disabilities. 38% of the respondents identified directly building housing for other particular special needs groups, including young families, people with dementia and people with learning difficulties. This type of housing would not otherwise be provided. Our case study from Eastbourne illustrated the way that market housing developers often overlooked the special needs of certain groups in their house-building activity, with the Council reporting it was motivated to take action directly to help providing housing suitable for older people.

Central government data does not cover all housebuilding activity by local authorities. The 2018 survey asked for the number of housing units delivered by the local authority using all means of direct delivery. Most respondents did not answer, but there was evidence of a total of 8,992 units delivered: 3,803 affordable (42%), 2,079 social (23%), 943 intermediate (10%), 1,428 for sale (16%) and 739 PRS (8%). We had not asked for this in our 2017 survey but in 2021 there was evidence of 20,249 homes having been delivered, of which 38% were for market sale. This is considerably higher than the 2018 survey and shows the increasing momentum around housing being delivered by local authorities. In Birmingham, the local authority reported in a roundtable discussion that the council (through its Birmingham Municipal Housing Trust, which is not a company but a brand for the council’s HRA) had built more housing in the city than any private developer over the last year. There is therefore evidence of emerging and growing activity across England as councils become more confident, increase their skills and capacity, extend their repertoire of housing interventions and share between local authorities how to secure longer term finance.

Barriers to engaging in direct delivery

As well as identifying the motivations, means and methods of those councils engaged in housing delivery, we also explored perceived challenges and barriers. Those local authorities not directly engaged in the direct delivery of housing were asked to specify the reason(s) for this. The three key issues identified were lack of funding, lack of land and lack of expertise and these are consistent over all three surveys.

Respondents were also asked about the main challenges in delivering more homes through their HRA or general fund even if they were already delivering some new housing. A wide range of barriers were identified. Lack of an HRA and/or having transferred stock were mentioned several times. Having a retained stock of council housing, which acts as an asset against which there can be borrowing to fund new housing development was often a starting point for many councils in their reengagement in housing developed. Nevertheless, while RTB remains in England, it removes the control of the council’s investment in housing and undermines efforts to maintain numbers of truly affordable houses. Using companies means that the council developed properties can be retained in council ownership (although they cannot properly be ‘social housing’).

The risk appetite and priorities (of officers, councillors or both) was sometimes a barrier, and in a few cases, it was considered that local housing associations were delivering well with the council. While the approach taken varies, strong local leadership and focus on the outcomes often seemed vital: those councils achieving the greatest level of delivery of housing had strong political leadership supporting the establishment of specific multi-professional housing teams that deal with all aspects of housing delivery across the council such as Plymouth, Bristol, Southwark and Hackney. This is accompanied by a focus on specific site delivery approaches including providing a single-named officer contact for each site as in Doncaster. Council leaders have been willing to invest this level of political capital because they are in charge of their own decision-making and can expect direct returns.

Funding remains a challenge for authorities, particularly in delivery of affordable housing. A lack of central government grant means many authorities are trying to develop market housing to cross-subsidise affordable housing, but this still does not usually allow sufficient to be developed compared to housing need. In relation to establishing housing companies, the key challenge was understanding company as opposed to local authority roles, followed by specific skills required for the local authority acting as a developer. A long list of ‘other’ challenges was also specified, for example, there were concerns about the risk of legal challenge over state aid and capacity of local authority staff to be company directors.

The most common barrier identified in the 2018 survey (and second most common in 2017) was, a lack of land on which to develop new housing. This can include both land owned by authorities to develop or sites that are both available and suitable to develop. The same survey found that 61% of authorities are acquiring more land and/or buildings as part of a longer-term investment strategy to support income. Secondly, for those authorities directly delivering housing, 95% are building on their own land, 44% are purchasing sites to develop, 42% are purchasing existing residential buildings, 17% are using land from the One Public Estate initiative (which seeks to make available excess land from one part of the public sector for another) and 13% are using other public land. Most buildings are on local authority owned land and indeed it seems this is how most local authorities start out their own direct delivery of housing. The data in our 2021 survey was similar.

The different scale of land holdings between authorities can mean there is some variation in the ease with which councils can start out re-engaging in housing delivery. In the past, there was frequently a focus on selling surplus land to generate short-term income (Christophers Citation2017). This is changing. In the most successful authorities, in order to develop housing, all land in the council’s ownership and control has been reviewed, not just that previously considered suitable for housing. Some councils like Harrogate and Plymouth are finding that they are identifying many more sites for varied types of housing, including for self-build. Other councils are repurposing their sites with BCP council using over 20 surface car parks for housing development. These actions can be undertaken using local powers, not reliant on central government.

The final area of challenge was having the necessary development skills, including specialist and experienced staff recruitment and retention. After so many years of councils not building housing, these skills have been lost. There is a very active market for those with development experience, and it is hard to keep a stable team. Housing development also needs other professionals such as planners, finance, legal and procurement to be on top of the new and emerging arrangements for housing delivery, which can be harder in the face of austerity-led reductions to teams. In some cases, the housing development part of the Council is having to cross-subsidise staff in other areas to get the support needed. Some councils, for example, Cambridge and Haringey, have included ‘shadowing’ of their staff in all commercial contracts or providing new opportunities to train as project managers so their own staff could be upskilled.

There has been some sharing of knowledge between different authorities and facilitation by the Greater London Authority (GLA) of this for London borough councils. This need for strong leadership and learning within authorities illustrates that it is far from straightforward for authorities to expand housing delivery, and some of the challenges relate to the very austerity which they may be seeking to challenge.

Conclusions

Local authorities in England, like many internationally, have been through a period of significant financial pressures and continue to face major difficulties, particularly urban areas with high concentrations of deprivation who had previously been most reliant on central government grant funding under a now removed principle of ‘equalisation’ between funding and need (Hastings et al. Citation2017). Austerity has reduced funding and the ability to deliver services. At the same time, any funds that are available from the government come with strings and project preferences via ‘deals’ or, in relation to housing, specified projects supported by the government agency Homes England. At the same time, the gap between government housing and planning policy and the experience of meeting needs locally has been widening since 2010 and shows no sign of being addressed: proposals in a government reform ‘white paper’ for the planning system published last summer (MHCLG Citation2020) would further centralise planning allocations for market housing with no accompanying policy support for all other types of housing need. Without direct action, councils are facing increasing financial pressures to respond to homelessness, and older and younger people are locked out of the market. Taking direct action puts councils in control and potentially provides for longer term financial security. At present, this is changing the role of local authorities in meeting local needs and now appears to be welcomed by central government (Jenrick Citation2021), following a publicly preferred trend rather than instigating it.

As our evidence demonstrates, we are now seeing a slow but steady resurgence in local authority housing provision across England. That a re-emergence of housebuilding delivery activity has occurred at the same time as the consequences of a ‘downloaded austerity’ (Peck Citation2012) over the last decade is no coincidence: income generation, reducing expenditure (for example, money spent on temporary accommodation for the homeless) and taking back control of finance has been a strong motivation for councils in engaging in housebuilding again. In some ways, this is returning local authorities to their original position when they were first formed and were able to directly provide services including energy, water and public health (Crewe Citation2016; Skelcher Citation2017). It does suggest that the story of austerity is not just one of the retrenchment of the local state: certainly services have been cut in many areas and we do not ignore the very real challenges of dealing with COVID-19, but housing provision provides an example of an expansion of local government services.

We would argue that local authorities have been so susceptible to politically driven austerity because of an over-reliance on central government funding, which differentiates UK local government from almost all other countries (OECD Citation2020). The very real negative consequences of the funding cuts they have endured over the last decade may, however, have acted as a stimulus to taking back control and doing things for themselves. The growing activity in relation to housing delivery has involved experimentation evident as different authorities use a variety of locally-devised solutions driven by a range of motivations. Thompson et al. (Citation2020) propose a spectrum in these type of proactive responses by the local state from an apparently concerning ‘financialised municipal entrepreneurialism’ to a more progressive ‘new municipalism’ as part of ‘various municipalist mutations as part of an assemblage of competing adaptive and experimental strategies of governing in, against and beyond “late-entrepreneurial” urban political economy’ (Citation2020, 1173). In relation specifically to local housing companies, Penny and Beswick (Citation2018) raise concerns including over their accountability and potential to reduce social housing delivery on public land whilst Christophers (Citation2019) sees it more as a compromised means to a progressive end of ensuring the delivery of essential services under austerity and preferable to the previous practice of simply selling off local authority land for other actors to then profitably develop.

As we have found through our research, there are a wide range of activities associated with this resurgence of local authority housebuilding, for a range of purposes. Some authorities are simply seeking to maximise building new social housing and others are actively utilising local procurement for social purpose, in ways that accord more with the concept of new municipalism. Others are indeed seeking profit for purpose through acting as housing developers. Disentangling which authorities are apparently acting more progressively would be highly complex. At the more speculative end of commercial property development, there are challenges and risks (Morphet and Clifford Citation2020; NAO Citation2020). Some Victorian municipal enterprises faced significant difficulties during economic downturns (Skelcher Citation2017) and few authorities are likely to want to mimic the sharp tactics of private sector volume housebuilders in their path to high profits. The recent failure of Croydon Council’s local housing company, Brick-by-Brick, has highlighted some commercial risks (Inside Croydon 2020) albeit the difficulties with that authority’s budget were also related to wider commercial property speculation and difficulties going back to investments lost during the global financial crash in 2008.

Although there are certainly these risks, most authorities are seeking to use their housing delivery more to help actually deliver housing that matches local need rather than simply generate income. Nevertheless, in the longer term, if local authorities are able to become more self-financing again through their own efforts, such as providing housing, this is likely to change the relationship between local and central government (Morphet Citation2021). Davies et al. (Citation2020) suggest that in the UK local government is in an ‘abusive relationship’ with central government but through more locally generated activity and income, in the future they may be less responsive to central government’s nudged policy control and compliance regime. They may also gain more confidence, re-engage in service provision to each other and to become major employers in their areas. While austerity’s apparent intention appeared to reduce the role of local authorities in the state, it may result in more independence and greater confidence in the longer term. We may not yet be facing the ‘death of municipal England’ (Crewe Citation2016) but rather the potential for an active expansion of income generating activity with social benefit and longer-term independence from central government. The path towards this will doubtless be rocky at times, but a progressive new municipalism is possible.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the anonymous referees and editor for their feedback on drafts of this paper. We are also particularly grateful to all the local government officers across England who have taken the time to complete our surveys and participate in our research despite the workload challenges inherent in everyday life in the local state under austerity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ben Clifford

Dr Ben Clifford is Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Planning, UCL. His research interests centre on the relationship between spatial/urban and regional planning and the state with a particular focus on reform in the UK. He was co-author for the book ‘Reviving Local Authority Housing Delivery’ and lead author for the books ‘Understanding the Impacts of Deregulation in Planning’ and ‘The Collaborating Planner?’ as well as numerous journal articles.

Janice Morphet

Professor Janice Morphet is Visiting Professor at the Bartlett School of Planning, UCL. Janice’s research interests centre on spatial planning, multilevel governance with a particular focus on the UK and Ireland, UK/EU relations and Brexit. Janice was co-author for the book ‘Reviving Local Authority Housing Delivery’ and author of the books Outsourcing’ (2021), Beyond Brexit (2017) and The Impact of COVID-19 on Devolution: Recentralising the British State Beyond Brexit?. (2021) in addition to other books and journal articles on planning, housing, local government and the EU.

References

- Bailey, D., and M. Wood. 2017. “The Metagovernance of English Devolution.” Local Government Studies 43 (6): 966–991. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1359165.

- Barnett, N., S. Griggs, S. Hall, and D. Howarth. 2021. “Local Agency for the Public Purpose? Dissecting and Evaluating the Emerging Discourses of Municipal Entrepreneurship in the UK.” forthcoming in Local Government Studies: 1–22. doi:10.1080/03003930.2021.1988935.

- Beswick, J., and J. Penny. 2018. “Demolishing the Present to Sell off the Future? The Emergence of ‘Financialized Municipal Entrepreneurialism’ in London.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4): 612–632. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12612.

- Christophers, B. 2017. “The State and Financialization of Public Land in the United Kingdom.” Antipode 49 (1): 62–85. doi:10.1111/anti.12267.

- Christophers, B. 2019. “Putting Financialisation in Its Financial Context: Transformations in Local Government‐led Urban Development in Post‐financial Crisis England.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (3): 571–586.

- Clayton, J., C. Donovan, and J. Merchant. 2016. “Distancing and Limited Resourcefulness: Third Sector Service Provision under Austerity Localism in the North East of England.” Urban Studies 53 (4): 723–740. doi:10.1177/0042098014566369.

- Clifford, B., J. Ferm, N. Livingstone, and P. Canelas. 2019. Understanding the Impacts of Deregulation in Planning. London: Palgrave Pivot.

- Cochrane, A. 2016. “Thinking about the ‘Local’ of Local Government: A Brief History of Invention and Reinvention.” Local Government Studies 42 (6): 907–915. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1228530.

- Crewe, T. 2016. “The Strange Death of Municipal England.” London Review of Books 38 (24): 6–8.

- Davies, J. S., and I. Blanco. 2017. “Austerity Urbanism: Patterns of Neo-liberalisation and Resistance in Six Cities of Spain and the UK.” Environment & Planning A 49 (7): 1517–1536. doi:10.1177/0308518X17701729.

- Davies, J. S., A. Bua, M. Cortina-Oriol, and E. Thompson. 2020. “Why Is Austerity Governable? A Gramscian Urban Regime Analysis of Leicester, UK.” Journal of Urban Affairs 42 (1): 56–74. doi:10.1080/07352166.2018.1490152.

- Dunning, R., A. Inch, S. Payne, C. Watkins, A. While, H. Hickman, and D. Valler. 2014. “The Impact of the New Homes Bonus on Attitudes and Behaviours.” Project Report DCLG.

- Fitzgerald, A., and R. Lupton. 2015. “The Limits to Resilience? The Impact of Local Government Spending Cuts in London.” Local Government Studies 41 (4): 582–600.

- Forrest, R., and A. Murie. 2014. Selling the Welfare State: The Privatisation of Public Housing. Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames.

- Fraser, A. 2010. “The Craft of Scalar Practices.” Environment & Planning A 42 (2): 332–346. doi:10.1068/a4299.

- Gallent, N., D. Durrant, and P. Stirling. 2018. “Between the Unimaginable and the Unthinkable: Pathways to and from England’s Housing Crisis.” Town Planning Review 89 (2): 125–144. doi:10.3828/tpr.2018.8.

- Gamble, A. 2015. “Austerity as Statecraft.” Parliamentary Affairs. 68(1): 42-57.July.

- Gardner, A. 2017. “Big Change, Little Change? Punctuation, Increments and Multi-layer Institutional Change for English Local Authorities under Austerity.” Local Government Studies 43 (2): 150–169. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1276451.

- Hackett, P. 2017. Delivering the Renaissance in Council-built Homes: The Rise of Local Housing Companies. London: Smith Institute.

- Hastings, A., N. Bailey, G. Bramley, and M. Gannon. 2017. “Austerity Urbanism in England: The ‘Regressive Redistribution’ of Local Government Services and the Impact on the Poor and Marginalised.” Environment & Planning A 49 (9): 2007–2024. doi:10.1177/0308518X17714797.

- Hastings, A., N. Bailey, M. Gannon, K. Besemer, and G. Bramley. 2015. “Coping with the Cuts? The Management of the Worst Financial Settlement in Living Memory.” Local Government Studies 41 (4): 601–621.

- Haughton, G., I. Deas, S. Hincks, and K. Ward. 2016. “Mythic Manchester: Devo Manc, the Northern Powerhouse and Rebalancing the English Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 9 (2): 355–370. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsw004.

- Jacobs, K., R. G. Atkinson, A. Spinney, V. Colic Peisker, M. Berry, and T. Dalton. 2010. “What Future for Public Housing?” A critical analysis at https://eprints.utas.edu.au/9623/1/AHURI_Research_Paper_What_future_for_public_housing_A_critical_analysis-4.pdf

- Jenrick, R. 2021. speech to LGA Annual Conference 6 July https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/local-government-association-annual-conference-2021-secretary-of-states-speech accessed 26 July 2021

- John, P. 2014. “The Great Survivor: The Persistence and Resilience of English Local Government.” Local Government Studies 40 (5): 687–704. doi:10.1080/03003930.2014.891984.

- Jones, C., and A. Murie. 2008. The Right to Buy: Analysis and Evaluation of a Housing Policy. Vol. 18. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kennett, P., G. Jones, R. Meegan, and J. Croft. 2015. “Recession, Austerity and the ‘Great Risk Shift’: Local Government and Household Impacts and Responses in Bristol and Liverpool.” Local Government Studies 41 (4): 622–644.

- Lauermann, J. 2018. “Municipal Statecraft: Revisiting the Geographies of the Entrepreneurial City.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1177/0309132516673240.

- Letwin, O. 2018. Independent Review of Build Out: Draft Analysis. London: HM Government.

- LGA. 2018. “Local Government Association Briefing Estimates Day Debate Ministry of Housing.” Communities and Local Government relating to homelessness at https://www.local.gov.uk/parliament/briefings-and-responses/estimates-day-debate-ministry-housing-communities-and-local

- LGA. 2020. “Housing Backlog – More than a Million Homes with Planning Permission Not yet Built.” https://www.local.gov.uk/about/news/housing-backlog-more-million-homes-planning-permission-not-yet-built

- Lowndes, V., and A. Gardner. 2016. “Local Governance under the Conservatives: Super-austerity, Devolution and the ‘Smarter State’.” Local Government Studies 42 (3): 357–375. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1150837.

- Lowndes, V., and K. McCaughie. 2013. “Weathering the Perfect Storm? Austerity and Institutional Resilience in Local Government.” Policy and Politics 41 (4): 533–549. doi:10.1332/030557312X655747.

- Lund, B. 2017. Understanding Housing Policy. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Matthews, P., G. Bramley, and A. Hastings. 2015. “Homo Economicus in a Big Society: Understanding Middle-class Activism and NIMBYism Towards New Housing Developments.” Housing, Theory and Society 32 (1): 54–72. doi:10.1080/14036096.2014.947173.

- MHCLG. 2020. “White Paper: Planning for the Future.” Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, London

- MHCLG (2021). Retained Right to Buy receipts and their use for replacement supply: guidance at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/retained-right-to-buy-receipts-and-their-use-for-replacement-supply-guidance

- Morphet, J. 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 on Devolution Recentralising the British State beyond Brexit? Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Morphet, J., and B. Clifford. 2017. “Local Authority Direct Provision of Housing.” https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/1891/localauthoritydirectprovisionofhousing2017.pdf

- Morphet, J., and B. Clifford. 2019. “Local Authority Direct Provision of Housing.” Continuation research at https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/2043/local-authority-direct-delivery-of-housing-ii-continuation-research-full-report.pdf

- Morphet, J., and B. Clifford. 2020. Reviving Local Authority Housing Delivery: Challenging Austerity Through Municipal Entrepreneurialism. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Morphet, J., and B. Clifford. 2021. “Local Authority Direct Provision of Housing.” Third research report at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/planning/sites/bartlett_planning/files/morphet_and_clifford_2021_-_local_authority_direct_delivery_of_housing_iii_report43.pdf

- NAO. 2016. Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities: Capital Expenditure and Resourcing. London: NAO.

- NAO. 2017. Housing in England Overview. London: NAO.

- NAO. 2018. Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities 2018. London: NAO.

- NAO. 2019. Planning for New Homes. London: NAO.

- NAO. 2020. Local Authority Investment in Commerical Property. London: NAO.

- OECD. 2020. Enhancing Productivity in UK Core Cities Connecting Local and Regional Growth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Overmans, J. F. A., and M. Noordegraaf. 2014. “Managing Austerity: Rhetorical and Real Responses to Fiscal Stress in Local Government.” Public Money & Management 34 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1080/09540962.2014.887517.

- Peck, J. 2012. “Austerity Urbanism.” City 16 (6): 626–655. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.734071.

- Peck, J. 2014. “Pushing Austerity: State Failure, Municipal Bankruptcy and the Crises of Fiscal Federalism in the USA.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst018.

- Penny, J. 2017. “Between Coercion and Consent: The Politics of “Cooperative Governance” at a Time of “Austerity Localism” in London.” Urban Geography 38 (9): 1352–1373. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1235932.

- Phelps, N., and J. Miao. 2019. “Varieties of Urban Entrepreneurialism.” forthcoming in Dialogues in Human Geography. 10(3): 304-321.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 2018. Control and Power in Central-local Government Relations. Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames.

- Shaw, K., and M. Tewdwr-Jones. 2016. “Disorganised Devolution”: Reshaping Metropolitan Governance in England in a Period of Austerity.” Raumforschung Und Raumordnung-Spatial Research and Planning 75 (3): 211–224. doi:10.1007/s13147-016-0435-2.

- Skelcher, C. 2017. “An Enterprising Municipality? Municipalisation, Corporatisation and the Political Economy of Birmingham City Council in the Nineteenth and Twentyfirst Centuries.” Local Government Studies 43 (6): 6, 927–945. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1359163.

- Skidelsky, R. 2015. “Austerity: The Wrong Story.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 26 (3): 377–383. doi:10.1177/1035304615601588.

- Somerville, P. 2016. “Coalition Housing Policy in England.” The Coalition Government and Social Policy: Restructuring the Welfare State 153-178.

- Standring, A., and J. Davies. 2020. “From Crisis to Catastrophe: The Death and Viral Legacies of Austere Neoliberalism in Europe?” Dialogues in Human Geography 10 (2): 146–149. doi:10.1177/2043820620934270.

- Taylor‐Gooby, P. 2012. “Root and Branch Restructuring to Achieve Major Cuts: The Social Policy Programme of the 2010 UK Coalition Government.” Social Policy & Administration 46 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00797.x.

- Thompson, M. 2020. “What’s so New about New Municipalism?” Forthcoming in Progress in Human Geography. 45(2): 317-342.

- Thompson, M., V. Nowak, A. Southern, J. Davies, and P. Furmedge. 2020. “Re-grounding the City with Polanyi: From Urban Entrepreneurialism to Entrepreneurial Municipalism.” Environment & Planning A 52 (6): 1171–1194. doi:10.1177/0308518X19899698.

- Ward, K., J. Newman, P. John, N. Theodore, J. Macleavy, and A. Cochrane. 2015. “Whatever Happened to Local Government? A Review Symposium.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 435–457. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1066266.

- Wilson, W. 2015. The New Homes Bonus Scheme. London: House of Commons Library Standard Note.