ABSTRACT

Residents of marginalised neighbourhoods have long been governed as a vulnerable group in need of help. Increasingly, however, they are expected to be active citizens and (co-)creators in improving their neighbourhood. While much is written about the shift towards more participatory governance, less is known about how this shift manifests in the work practice of urban professionals, particularly in marginalised neighbourhoods and in terms of citizen (dis)empowerment. This paper explores how urban professionals give shape to citizen participation in a marginalised Dutch neighbourhood. I found that they navigated between narratives of ‘vulnerability’ and ‘active citizenship’ and employed ‘selective empowerment’: a differentiated approach in which they ascribed a significant supportive role to themselves and facilitated participation within a normative framework. The research offers a more nuanced image of ‘empowerment’ than previous studies suggest, demonstrating that a discursive shift in governance approach is not automatically synchronised with urban professionals’ work practice.

1. Introduction

In the early summer of 2019, the municipality of Tilburg, a medium-sized Dutch city, donated a vacant building to the neighbourhood of Tilburg-West. The goal was to provide residents and professionals in West with an accessible space in which to meet and to experiment with neighbourhood initiatives. In the words of the then district alderman, ‘What makes me proud, is that as a municipality we’ve succeeded in participating in and connecting with initiatives of residents and professionals’ (Policy Document 7, 2019). The purchase of the ‘Neighbourhood Home’ was part of the municipality’s ‘PACT’ approach, PACT being an abbreviation of ‘People Acting in Community Together’, a novel participatory governance approach in three marginalised neighbourhoods, including Tilburg-West.

The Tilburg PACT approach is illustrative of a participatory turn in the governance of urban marginality. Residents of marginalised neighbourhoods have long been governed as a problematic group, living in ‘problem neighbourhoods’ or ‘priority zones’, and in need of help from the government (Dikeç Citation2007; Hancock and Mooney Citation2013; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2004; Van Kempen and Bolt Citation2009). Nowadays, however, they are invited and, indeed, expected to take part in government efforts to improve their neighbourhood. Much of the existing scholarship has focused on this shift towards more participatory, shared and networked forms of governance (Hajer Citation2003; Pierre Citation2000; Provan and Kenis Citation2008), but less is known about how this shift manifests in the work practice of urban professionals, particularly in marginalised neighbourhoods. While the literature agrees that urban professionals play a key role in realising participation (Durose and Lowndes Citation2010; Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2018; Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2020; Escobar Citation2021; McMullin Citation2022; Agger and Tortzen Citation2022), it is inconclusive about whether and how in this role they (dis)empower citizens.

On the one hand, scholars suggest that urban professionals empower citizens, thanks to their ability to navigate between different roles and to mediate between ‘the state’ and ‘the people’ due to their unique position in between (De Graaf, Van Hulst, and Michels Citation2015; Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2018, Citation2020; Tonkens and Verhoeven Citation2019; Van de Wetering and Kaulingfreks Citation2020). Others, however, maintain that the work of urban professionals disempowers citizens, because it reproduces existing inequalities (Lombard Citation2013; Levine Citation2017; Lupien Citation2018; Stapper and Duyvendak Citation2020; Hammond Citation2021). Thus, well-intended efforts to work together with marginalised groups may have unintended opposite effects, doing more harm than good. This raises the following research question, which is central to this paper: how do urban professionals, in the context of the shift towards more citizen-centred approaches in the governance of urban marginality, give shape to citizen participation in marginalised neighbourhoods?

To answer this question, this paper explores the work of urban professionals in the participatory Tilburg PACT approach in general and in the Neighbourhood Home in particular. From 2019 to 2021, I closely followed the work of these professionals with an in-depth ethnographic study including document analysis, participant observation and semi-structured interviews. I found that in Tilburg, urban professionals navigated between narratives of ‘vulnerability’ and of ‘active citizenship’ and employed ‘selective empowerment’: a differentiated approach towards citizen participation in which urban professionals ascribed a significant supportive role to themselves and facilitated participation within a normative framework. Based on these findings, this paper advances existing knowledge in two ways. First, it demonstrates that a shift towards more citizen-centred approaches in the governance of urban marginality may take place on a discursive level, but that this is not necessarily synchronised with the work practice of urban professionals. Second, it proposes a more nuanced understanding of the work of urban professionals beyond mere empowerment or disempowerment.

2. Theorising participatory governance in marginalised neighbourhoods

2.1. Towards citizen participation in ‘problem neighbourhoods’

Governments have deployed a variety of policy programmes in response to the spatial segregation of marginalised groups and the concentration of inequality, crime, unemployment and poverty in specific urban areas (Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003). With these programmes, governments have acted to ‘remedy’ or ‘manage’ the ‘disintegrating processes’ that manifest within marginalised neighbourhoods and beyond (Uitermark Citation2014: 1,432). In doing so, they have often identified them as ‘problematic’ and/or ‘vulnerable’ and targeted them, as ‘problem neighbourhoods’, ‘priority zones’ or ‘deprived neighbourhoods’, with prioritised urban policy (Wacquant Citation2007; Dikeç Citation2007; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2004; Van Kempen and Bolt Citation2009; Hancock and Mooney Citation2013). Initially, such programmes were generally state-led, top-down and focused on managing problems ‘from the outside’, with residents perceived as ‘subjects’ of state-governed projects and as ‘passive citizens’ (Uitermark Citation2014; Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003).

In recent decades, however, governments have turned to local and participatory governance approaches to improve neighbourhoods and tackle marginalisation (Bartels Citation2018; Häikiö Citation2012; Herrting and Kugelberg Citation2017; Michels Citation2012; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015; Michels and De Graaf Citation2017). These relatively new forms of governance are part of a larger shift ‘from government to governance’, in which the state increasingly seeks to share its power with other actors (Hajer Citation2003; Pierre Citation2000) through collaborative (Ansell and Gash Citation2008) or network governance structures (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Urban residents, as one such group of actors, are activated and expected to participate and take responsibility in making changes in their neighbourhood (Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003; Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2013; Tonkens and Verhoeven Citation2019).

Thus, a shift is identifiable in the governance of urban marginality: from marginalised neighbourhoods as inherently problematic with residents as a group in need of help through state-led programmes, to marginalised neighbourhoods as spaces of opportunities where residents are looked upon as the co-creators of their prosperous and improved neighbourhoods within participatory approaches.

2.2. The role of urban professionals: empowering citizens?

Urban professionals, both municipal and non-municipal, and ranging from civil servants to professionals working for welfare organisations and other social partners linked to the neighbourhood, play an important role in realising participatory approaches (Durose and Lowndes Citation2010; Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2018; Blijleven, Van Hulst, and Hendriks Citation2019; Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2020; Escobar Citation2021; McMullin Citation2022; Agger and Tortzen Citation2022; Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2022). However, what their role exactly entails remains underexposed, as previous research suggests that the work of urban professionals can empower as well as disempower citizens (Kampen and Tonkens Citation2019).

Empowerment is a primary aim of participatory approaches (Bacqué and Biewener Citation2013; Fung Citation2004), which is viewed as necessary to transform residents from passive to active citizens (Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003) and to help ‘excluded citizens become the pillars supporting the solutions to their own problems’ (Nussbaumer and Moulaert Citation2004, 250). This is especially so in marginalised neighbourhoods, where citizen participation appears particularly difficult to foster (De Graaf, Van Hulst, and Michels Citation2015; Tonkens and Verhoeven Citation2019; Brandsen Citation2021). Here, authors argue, residents are ‘hard to reach’ because they have less resources, skills and social capital, and feel excluded and powerless (Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2018).

On empowerment, the literature provides contrasting perspectives. One holds that urban professionals empower citizens, activating and enabling them to participate in (government) projects and activities (De Graaf, Van Hulst, and Michels Citation2015; Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2018). They enhance participation by providing citizens with resources and networks, motivating and mobilising them, and by being responsive (Lowndes, Pratchett, and Stoker Citation2006; J. Bakker et al. Citation2012). This can take many forms: facilitating discussions among residents, helping residents with a subsidy application, and having informal conversations over coffee at a community centre. By combining such different roles, as a friend, leader, representative and mediator, urban professionals may not only encourage citizens to participate, but also make them more self-confident in their participation (Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2020). Being positioned between ‘the state’ and ‘the citizens’, authors argue, urban professionals speak both languages and are able to translate from one to the other, to build bridges and to play an ‘intermediary’ role (De Graaf, Van Hulst, and Michels Citation2015; Durose et al. Citation2016; Van de Wetering and Kaulingfreks Citation2020).

Another perspective, however, suggests that in realising participatory approaches, urban professionals in fact disempower urban residents. This is because despite participatory aims, decision-making authority may remain in the hands of public officials, or be shared only with a small group of already privileged residents. For instance, the blurry boundaries of ‘the community’ may enable urban professionals to exclude some residents’ input or dissent from community engagement (Levine Citation2017). Or the shape of participatory projects, for instance, a co-creation workshop, can lead urban professionals and residents to make distinctions between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ citizens, favouring the interests of the former and directing resources to them (Stapper and Duyvendak Citation2020). Notwithstanding emancipatory aims, participatory projects may in practice be ‘an elite-led engineering of citizen engagement […] beyond the control of citizens themselves’ (Hammond Citation2021). This can result in reproduction of social inequalities between those involved and in residents’ power being undermined (Lombard Citation2013; Levine Citation2017; Lupien Citation2018; Stapper and Duyvendak Citation2020; Hammond Citation2021).

While the shift ‘from government to governance’ and towards citizen participation has been widely studied, less attention has gone to whether and how this shift manifests in the work practice of urban professionals, especially in marginalised neighbourhoods and in terms of citizen (dis)empowerment.

2.3. Governing marginalised neighbourhoods in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, urban policy has long focused on improving disadvantaged neighbourhoods by giving them priority attention (Van Kempen and Bolt Citation2009). But much like in other countries, the focus here has shifted over time. What began as state-led efforts to solve the problems of ‘deprived areas’ and ‘vulnerable people’ has evolved into more locally tailored initiatives, with the state retreating to the background and residents and other urban actors given foreground roles (Van der Velden and Can Citation2022; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2004).

This reorientation of Dutch urban policy began in the mid-1990s with the nationally implemented ‘Big Cities’ programme, which focused explicitly on ‘deprived areas’ and helping ‘vulnerable people’ to ‘escape from a disadvantaged situation’ (Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2004, 112). It additionally aimed to actively involve ‘all relevant stakeholders’, including local residents (ibid: 111). The Big Cities programme was supplemented by an action plan for ‘disadvantaged neighbourhoods’, also referred to as ‘Vogelaar neigbourhoods’, named after Ella Vogelaar, then Minister for Housing, Neighbourhoods and Integration (Van der Velden and Can Citation2022; Van Kempen and Bolt Citation2009). In the Big Cities programme, residents of the targeted neighbourhoods were positioned not only as passive citizens in need of government help, but were also to be actively involved as participants (Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003).

In the early 2010s, the Big Cities programme ended and the urban renewal phase gave way to a period of locally steered neighbourhood policy without financing or policy frameworks provided by the national government. Some have referred to this as ‘a policy vacuum’ in Dutch neighbourhood policy (Van der Velden and Can Citation2022; Uyterlinde, Boutellier, and De Meere Citation2021). This period coincided with the implementation of the 2007 Social Support Act and, starting in 2015, decentralisation of a wide range of social policy mandates to the municipal level. The national government presented this decentralisation as a call upon citizens to take responsibility for their own lives and neighbourhoods (Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2013; Bredewold et al. Citation2018), evoking the ideal of a ‘participatory society’, with active citizens who take care of one another and of society as a whole.

For neighbourhood policy, this meant that local actors were expected to deal with physical, social and economic issues in marginalised neighbourhoods. The result was first an almost decade-long impasse, as Dutch municipalities struggled to come to terms with budget cuts. Eventually, however, ‘attention for a broad, area-based approach in vulnerable neighbourhoods […] returned to the policy agenda’ (Van der Velden and Can Citation2022, 23). In the Netherlands, like in other European countries, local and participatory approaches are now central in urban policy for marginalised neighbourhoods. These approaches build on possibilities rather than (only) problems in the neighbourhood and aim to engage citizens, thereby tackling urban marginalisation from within.

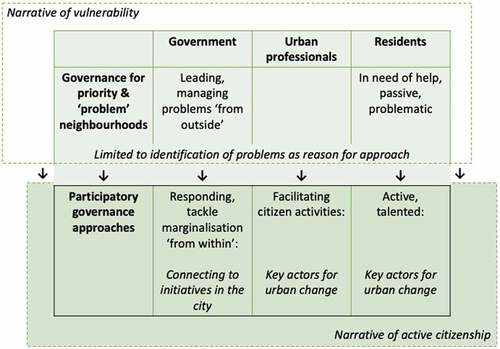

The Tilburg PACT approach is emblematic of this national and, indeed, broader shift to participatory approaches for the governance of marginalised neighbourhoods. Based on the existing literature, we would expect to see this shift materialise in the work of urban professionals in Tilburg: with a responding, rather than a leading (local) government, and urban professionals who facilitate residents’ activities and approach them as active and talented neighbourhood citizens ().

3. Methodological discussion

3.1. An ethnographic study of participatory governance in Tilburg

This study adopts an ethnographic case study design to examine how urban professionals give shape to citizen participation in marginalised neighbourhoods. The focus is on the city of Tilburg in the Netherlands, where urban professionals have sought to facilitate participation as part of the so-called PACT approach: a participatory governance programme aimed at tackling urban marginalisation. The Netherlands is an interesting setting to study urban marginalisation and participatory governance for two main reasons. First, increasing national inequalities have given rise to calls for more national investment in (social) policy to tackle marginalisation in urban neighbourhoods (PBL Citation2016; Leidelmeijer, Frissen, and van Iersel Citation2020). Second, urban residents are increasingly expected to participate actively and take responsibility for themselves and their surroundings in the ‘participation society’, with a coinciding rise in participatory governance approaches (Van de Wijdeven and Hendriks Citation2009; Verhoeven and Tonkens Citation2013; Musterd and Ostendorf Citation2023).

Within the Netherlands, the PACT approach in Tilburg is illustrative of the intensified government effort to tackle urban marginalisation through participatory approaches. I zoom in on the neighbourhood of Tilburg-West, that, in recent decades developed from a rather homogeneous working-class neighbourhood to a more heterogeneous neighbourhood with rising socio-economic problems. While at the municipal level, efforts have been made for years to tackle these issues, the area has until recently not been included in national policy programmes for ‘deprived neighbourhoods’ such as the earlier mentioned ‘Vogelaar neighbourhoods’ (Leidelmeijer, Frissen, and van Iersel Citation2020). In 2018, the Tilburg municipality initiated the PACT approach in Tilburg-West and two other neighbourhoods. According to a biannual neighbourhood liveability assessment carried out among residents by the municipality, these three neighbourhoods were experiencing problems in several dimensions: physical space, socio-economic issues and safety. They were furthermore characterised by relatively high levels of poverty, unemployment and crime (Municipality of Tilburg Citation2021).

In West, the municipality and urban professionals initiated the ‘Neighbourhood Home’ as part of the PACT approach. Herein, the municipality purchased a vacant building in the neighbourhood, which it made available to the neighbourhood until its planned demolition. The building was to provide a base for improving opportunities to develop talent in the neighbourhood. Residents were asked to submit ideas about what to do with the building, and invited to start their own initiatives in it. Activities of urban professionals included facilitating participation of neighbourhood residents (e.g., organising meetings to discuss potential uses of the Neighbourhood Home), supporting citizen initiatives (e.g., helping residents draft business plans for initiatives in the Neighbourhood Home), creating institutional space for citizen initiatives (e.g., establishing lines of communication with a difficult-to-reach municipal department), and spending time with citizens during neighbourhood activities (e.g., a neighbourhood festival).

3.2. Data collection and analysis

Between 2019 and 2021, I followed the work of urban professionals involved in the PACT approach in general and in the Neighbourhood Home specifically. First, I analysed mission statements and communication materials, to develop an understanding of the discursive positioning of the approach. Second, I observed and participated in the weekly meetings of the core team at city hall and meetings in the neighbourhood of the working group focused on the Neighbourhood Home. I supplemented this with participant observation at ad hoc neighbourhood meetings and events, and with informal conversations with residents and the urban professionals involved in the approach. Third, 19 in-depth semi-structured interviews with residents and professionals involved in the Neighbourhood Home and the PACT approach added to my understanding of both what professionals do and what they say about what they do to facilitate participation in Tilburg-West.

Using an ethnographic methodology meant employing a sensibility ‘to glean the meanings that the people under study attribute to their social and political reality’ (Schatz and Schatz Citation2009, 5). My long-term presence in the field enabled me to experience the dynamics of the field first hand. Interviewing supplemented what I observed, giving me a better understanding of what respondents made of their experiences (Wolcott Citation1999; Marcuse and Cushman Citation1982). For over a year, I developed an embeddedness within city hall and within the neighbourhood, and in the spaces in between. By spending time with urban professionals and citizens, I built a multi-layered perspective on what it means to govern marginalised neighbourhoods.

The data – documents, extensive fieldnotes and interview transcripts – were analysed using a narrative analysis approach, moving from the understanding that people make sense of the world around them by developing narratives and that these stories in turn guide their actions (Somers Citation1994). With this narrative approach, I looked for patterns in what people said, but also in how they said it (Riessman Citation2005). Comparing the analyses of documents, fieldnotes and interviews enabled me to understand how the PACT approach was both discursively positioned and practiced by those involved.

I used different rounds of coding (Boeije and Bleijenbergh Citation2019). With the first, inductive, round of data analysis I identified key themes and patterns in the strategies employed by citizens and the state to make urban change. I found that how urban professionals talked about citizens and citizen participation was not neutral, and developed a focus on the way in which those involved in participatory approaches were ‘framing citizens’. After this, I took a more abductive approach, going back and forth between theory and data to identify how professionals perceived and gave shape to citizen participation. This resulted in identification of two broad narratives about people and place in the practices, conversations and documents I studied. These were narratives about ‘passive’ and ‘active’ citizens, about citizens ‘in need of help’ and ‘with agency’, and about ‘problematic’ neighbourhoods and neighbourhoods full of ‘talent’. In critical dialogue with the literature (Alvesson and Kärreman Citation2007: 1,266), I labelled these narratives of ‘vulnerability’ and of ‘active citizenship’.

I followed the neighbourhood approach throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Obviously, the pandemic impacted the research. Due to the pandemic, meetings at city hall moved almost completely online from March 2020 onwards. I thus participated in and observed these meetings in a virtual setting. The meetings in the neighbourhood were cancelled in March 2020, but recommenced in June in hybrid form with both online and offline participation and informal get-togethers. Overall, physical presence in the field was restricted, meetings moved online and informal interactions either did not take place or occurred online, making them more difficult to grasp. Still, I was able to continue the research, primarily thanks to the network I had built prior to the pandemic. It enabled me to maintain a close connection with the field and collect data in ‘remote’ ways. As such, I developed an understanding of the municipality’s approach, the Neighbourhood Home and the work of the professionals who gave shape to citizen participation in Tilburg-West.

4. Facilitating participation: narratives and practices of vulnerability and active citizenship

How do urban professionals, in the context of a shift towards more citizen-centred approaches in the governance of urban marginality, give shape to citizen participation in marginalised neighbourhoods? To answer this question, I first discuss the PACT approach’s discursive positioning within the PACT documentation. I then examine how the approach was put into practice by those involved, based on analysis of extensive observations and in-depth interviews. The section is concluded by introducing the concept of ‘selective empowerment’ to explain how urban professionals facilitated participation by navigating between narratives of vulnerability and active citizenship.

4.1. The PACT approach on paper: from vulnerability to active citizenship

4.1.1. Vulnerability

The PACT approach in Tilburg started from the identification of the PACT neighbourhoods as deprived neighbourhoods in need of priority government attention. In fact, the neighbourhoods’ deprivation, indicated by a biannual neighbourhood liveability assessment (Municipality of Tilburg Citation2021; W. Bakker et al. Citation2019), was the basis for their inclusion in the approach. The document analysis shows that this starting point was central in the discursive positioning of the PACT approach.

In 2018, a mission statement was put on paper to describe the PACT approach. According to this text:

[A] lot of people are dealing with an accumulation of challenges related to poverty, unemployment, education and health. This is a breeding ground for criminality; the youth in these neighbourhoods appear vulnerable for criminal influences. The municipality and partners have been working on these problems for years. (Policy Document 1, n. d.).

The problems of the neighbourhoods were presented similarly in communication materials published online and in print, for example:

In some parts of our city, exclusion, poverty, loneliness and crime are still a reality. This has to change. (Policy Document 4, November 2020).

We strive for everyone in Tilburg to reside, work and study; in short, to live, in a healthy and happy way. The reality is that in parts of our city, that ideal is far away. Exclusion, poverty, loneliness and crime for instance play a role there. Not every inhabitant of Tilburg experiences a good start, and not every resident is seen. (Policy Document 5, May 2020).

Residents of the three PACT neighbourhoods were thus presented as dealing with problems and challenges that needed to be solved. For Tilburg-West, these problems were further specified as ‘poverty’ and ‘vulnerability to criminal influences’ (Policy Document 2, 2019). In 2020, the framing of marginalised neighbourhoods and their residents as ‘vulnerable’ places and people gained a new dimension with the COVID-19 pandemic. Fifteen Dutch city mayors, including the mayor of Tilburg, stated that ‘residents in our most vulnerable areas are hard hit by the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis’ (Policy Document 6, 2020). They called on the national government to provide extra support for ‘the most vulnerable areas in our country’ (ibid.).

In the discursive positioning of the PACT approach, a first narrative can thus be identified, in which marginalised neighbourhoods are viewed as inherently problematic and its residents as having problems and as dependent on government aid. I call this the narrative of vulnerability.

4.1.2. Active citizenship

Although the problems in the neighbourhoods were the motivation for the PACT approach, the programme mission statement and communication materials also presented the neighbourhoods as a trove of talent and opportunities. Development of the neighbourhoods and the talents of their residents were central PACT themes (Policy Document 2, 2019; Policy Document 3, 2020). The approach sought to build on initiatives emanating from within the neighbourhoods. The residents, together with urban professionals, were said to know best what the neighbourhoods needed. According to the mission statement, ‘[T]he capacity and energy of the neighbourhood residents and partners guide the agenda’ (Policy Document 1, n.d.). In other communication materials, both urban professionals and neighbourhood residents were indicated as key actors for change. These stated that there was already participation, talent and agency in the neighbourhoods, and the approach merely needed to connect to these:

In the PACT movement, we connect to eleven initiatives in the city; initiatives that originated from society, from residents and from neighbourhood professionals. (Policy Document 4, 2020).

Not only the ability of citizens to participate in neighbourhood development was stressed, but also the strong need for citizens to be involved:

By connecting with the needs and qualities of professionals and neighbourhood residents, by connecting to developments [in the neighbourhood] and together, on the basis of equality, putting in our efforts; that is how we can make a difference together. (Policy Document 5, 2020).

A second narrative can thus be identified in the discursive positioning of the PACT approach in mission statements and policy documents: the narrative of active citizenship. Within this narrative, marginalised neighbourhoods are viewed as places of opportunities, potentials and power and their residents as agents of urban change.

While the targeted neighbourhoods and their residents were characterised as vulnerable in the sense that they were dealing with problems that needed to be fixed, the approach to do that built on the talent and agency within the neighbourhoods. The narrative of vulnerability was thus limited to the identification of problems as the reason for the approach and change was perceived as coming from within, rather than from the state. The ‘active citizenship’ narrative took central stage in the discursive positioning of the PACT approach, marking a shift from traditional state-led approaches to participatory approaches to tackle neighbourhood marginalisation (see ).

4.2. The PACT approach in practice: vulnerable residents and active citizens

However, the urban professionals tasked to realise the PACT approach in the neighbourhoods did not simply adopt the discursive shift in their work practice. Extensive observations of urban professionals’ interactions with residents at meetings for the Neighbourhood Home and in-depth interviews in which professionals reflected on their work revealed that they drew on both the narrative of vulnerability and that of active citizenship as they facilitated participation.

4.2.1. Vulnerability

Almost all of the professionals working in the neighbourhoods considered citizens unable to participate without their help (Interviews, September – December 2020): “‘If we leave them [residents] free, or if they have to figure it out for themselves, then not much will happen…’. (Fieldnotes, September 2020). Most urban professionals were convinced that they had an important role to fulfil. As one urban professional explained, ‘We shouldn’t overestimate self-reliance, saying “people can do it on their own now”. Maybe a neighbourhood like this needs the life-long support of professionals’ (Interview, October 2020). And in the words of a municipal employee working in the neighbourhoods, ‘vulnerable people are not simply capable [of participating]… You [as a professional] need to help much more, and need to get involved’ (Interview, September 2020).

This narrative of vulnerability was translated into practices of participation. For instance, during one meeting for the Neighbourhood Home, a professional working in the neighbourhood said that he spoke on behalf of the residents, ‘as an advocate for the initiatives [of residents]’. A neighbourhood council member responded by saying that soon the residents could all come together. However, another professional questioned the wisdom of that: ‘I wouldn’t do that … we need to keep the decision-making group as small as possible’ (Fieldnotes, November 2019).

In other settings, too, citizens were often absent from decision-making tables, despite the continuous underscoring of the relevance of citizen participation. At one of the first core team meetings I attended at city hall, there was a discussion about the team’s ambitions for the coming year. One team member raised the question:

Should we, at our office, put ourselves in the residents’ shoes? Or should we let residents join us?… And if they are not literally at the table, should we take them along in our thinking? (Fieldnotes, October 2019).

After having joined the city hall meetings for almost a year, I realised that at none of these meetings had neighbourhood residents been present (Fieldnotes, August 2020).

In addition to viewing residents as ‘vulnerable’ and ‘in need of help’, urban professionals considered some residents and/or their activities as ‘problematic’. For instance, when a group of youths in Tilburg-West took to the streets to (violently) protest a curfew order issued as a public health measure in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some professionals problematised not only the violent behaviour of those involved, but also the ‘rioting’ youths themselves that, according to them, did not represent or belong to the neighbourhood (Fieldnotes, April 2020).

Although urban professionals agreed that citizens’ perspectives should be taken into account at all times, they saw some citizens as too vulnerable or problematic. They wondered whether citizens should participate in all aspects of the approach or whether some aspects were better left to the professionals. In practice, this meant they spoke on behalf of citizens when including residents was viewed as possibly complicating things, and they executed tasks themselves when they viewed citizens as incapable of doing so. Drawing on a narrative of vulnerability, urban professionals appeared to see the participation of residents as necessarily embedded within a continuous support system, in which they themselves fulfilled a significant role.

4.2.2. Active citizenship

While urban professionals saw residents as vulnerable citizens in need of their help, they agreed there was a risk of professionals ‘taking over’ (Fieldnotes, September 2020). This was a recurrent topic, both at the city hall meetings and at the weekly meetings about the Neighbourhood Home. In the in-depth interviews, too, urban professionals stressed the importance of and wondered how the Neighbourhood Home could really belong to the neighbourhood rather than the professionals (Fieldnotes, September 2020; Interviews, September – December 2020). In this regard, the urban professionals drew on the narrative of active citizenship, stressing, as read in the PACT documentation, that the approach should and could build on the talent and agency of residents. Translating this into practice, however, appeared less straightforward.

Among urban professionals, the question of how citizens should participate, raised debate. At one of the many events I attended in a PACT neighbourhood, I joined a youth worker, a municipal professional and a neighbourhood council member in a discussion entitled ‘Power of the People’. We talked about different ways citizens could be active, such as through neighbourhood councils, participatory budgets and the organisation of a small party by neighbourhood youths. The youth worker stressed the importance of that last kind of initiative, saying that is also power of the people. The neighbourhood council member agreed. The municipal professional commented that ‘you can’t only build with small things’ and stressed the importance of ‘the bigger movement’ (Fieldnotes, June 2019).

Citizens themselves also had ideas about ‘right’ (and ‘wrong’) kinds of participation. They shared these in interactions with the professionals, and the professionals took these views into consideration (Fieldnotes, February 2020):

“We were talking about the composition of the neighbourhood council. [A neighbourhood council member] explained that the entire neighbourhood was represented: youths, the elderly. He told me that the council had also tried to attract people with a migration background. Initially, he said, they were very enthusiastic. But after three invitations they still had not come to the meeting. I asked why not. He said, ‘they don’t have a meeting culture… they have informal … they don’t like the formal. If we put a dish of food on the table, then they come. Just talking while having dinner. But then I wonder, do we need to adjust to your culture, or do you need to adjust to ours?’ (Interview, November 2020).

Similarly, in relation to the COVID curfew protest, the activities of the youths were not seen as an expression of active citizenship. Rather, ‘rioting’, ‘problematic’ youths were redirected to appropriate forms of participation: in response to the unrest that had arisen, youth services established a youth council to facilitate dialogue and hear youths’ views on their lives and the neighbourhood (Fieldnotes, April 2020).

Urban professionals thus viewed some citizens and their ways of engaging as fitting the (traditional) mould of active citizenship, while others were labelled ‘problematic’ to some extent and in need of their help and adjustment. This meant that certain forms of participation, and the citizens enacting them, were welcomed in the neighbourhood approach, more so than, for instance, ‘rioting’ (youths) or informal dinner gatherings where the neighbourhood was discussed without formal agendas or meeting minutes.

In sum, in their interactions with citizens, urban professionals drew on both the narrative of vulnerability and that of active citizenship. This became apparent in the role that urban professionals ascribed to themselves vis-à-vis citizens and in what they saw as ‘appropriate’ active citizenship.

4.3. Facilitating participation through selective empowerment

The participatory turn found in PACT policy documents and communication materials appeared less straightforward in the work practice of urban professionals. While urban professionals acknowledged and agreed with the participatory aims as put on paper, they did not blindly copy these to their work practice. Rather, they made the participatory ideas their own as an urban professional, involved in the Neighbourhood Home, explained:

The political discourse wants people to take matters into their own hands. Realise the participatory society, strengthen the local democracy, [that is] even the agenda of this municipal council [.] that needs to be translated [to the neighbourhood].

Observations of their meetings, both at city hall and in the neighbourhood, and in-depth interviews showed that the urban professionals navigated between the narratives of vulnerability and active citizenship as they sought to facilitate participation. They invited residents to participate as active citizens and important actors within the governance of their neighbourhood, while simultaneously viewing them as a ‘vulnerable’, and sometimes also as a ‘problematic’ group in need of help and not simply able to participate. In the words of an urban professional, involved in the Neighbourhood Home:

Deciding for residents, as someone who knows it all, that is of course not the current trend […], but it is something that people end up going back to at times.

The result was that urban professionals ultimately took a differentiated approach to citizen participation in which some kinds of participation (‘riots’) were less welcomed than others (‘meetings’), and in which ‘vulnerable residents’ were approached as ‘active citizens’ only in a relationship of support with the professionals themselves. This was illustrated, for instance, when after a period of relatively few meetings, due to COVID-19, an online gathering over coffee was organised to discuss the latest developments in the Neighbourhood Home. One professional used a creative metaphor to describe their contribution:

Participation needs to be supported. … We [professionals] need to create a canvas on which participation can go nuts. But you can’t expect a painting to arise without bringing the brushes. (Fieldnotes, September 2020).

Urban professionals presented their relationship with residents, rather than the residents themselves, as the pillar supporting solutions to the citizens’ and neighbourhoods’ problems. This was in part because they viewed the residents as incapable of participating in appropriate ways and/or on their own (Fieldnotes, February – March 20, September 2020). In addition, according to some urban professionals, it was difficult for residents of marginalised neighbourhoods to participate because they had other priorities (Interviews, October 2020).

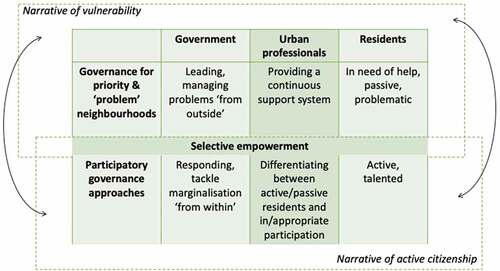

In the PACT approach in general and in the Neighbourhood Home specifically, citizens participated within a relationship of support with urban professionals and within a normative framework of ‘appropriate’ expressions of active citizenship. As such, not everybody was empowered as an ‘active citizen’. Neither was the disempowerment of residents the only dynamic at work. Rather, as urban professionals navigated between the narratives of vulnerability and active citizenship, they drew boundaries between active citizens who could and did participate in more traditional formats, and vulnerable citizens who did not and therefore needed their help. This ‘selective empowerment’ can be understood as a form of facilitating participation in between vulnerability and active citizenship (). It acknowledges the vulnerability of residents and retains the aim of empowerment, albeit in differentiated ways.

5. Conclusion and discussion

This paper investigated how urban professionals may give shape to citizen participation in their work in marginalised neighbourhoods in the context of the current shift in states’ approach to the governance of urban marginality: from state-led problem solving aimed at ‘vulnerable’ groups in need of ‘outside’ help, to a more bottom-up, participatory orientation aimed at facilitating opportunities ‘from within’. Particularly, I sought to understand how urban professionals translated this shift into their day-to-day work. My analysis was based on an in-depth ethnographic case study in the Dutch city of Tilburg, where urban professionals were facilitating participation of neighbourhood residents as part of a new citizen-centred approach with the aim to tackle urban marginalisation.

In Tilburg, I found that while at the discursive level the participatory approach was positioned as embodying active citizenship, in the work practice of the involved urban professionals the idea of vulnerable places and people in need of help was not so easily replaced. Urban professionals drew on both a narrative of ‘vulnerability’ and of ‘active citizenship’, despite their conflicting assumptions about and contrasting expectations of residents. Residents were viewed as having problems and simultaneously as having talents and capabilities and were assumed to be in need of help from the government and from professionals, while also being able to come up with and execute initiatives to improve the neighbourhood.

Urban professionals navigated between these coexisting and indeed contradictive narratives as they facilitated participation in the neighbourhood. This resulted, first, in urban professionals ascribing a significant role to themselves as a continuous support system for citizens. This led, second, to the participation of citizens within a normative framework of ‘appropriate’ or more traditional expressions of active citizenship. As they translated the broader shift in the governance of urban marginality to their work practice, urban professionals reproduced existing categories of vulnerability, while reworking the meaning of ‘active citizenship’ or ‘citizen participation’ with marginalised groups. Therefore, in Tilburg, their work cannot be classified simply as either empowerment or disempowerment. Rather, I classify their work as ‘selective empowerment’. This is a more nuanced form of facilitating participation in between vulnerability and active citizenship that puts central the relationship between citizens and urban professionals. Acknowledging vulnerability is then not (only) a reproduction of existing inequalities, as previous studies suggest, but also an embedded approach employed by urban professionals to facilitate context-specific citizen participation against the background of urban marginalisation.

This research makes three main contributions. First, it advances existing knowledge on the role of urban professionals who facilitate participation in marginalised neighbourhoods by providing a more nuanced view of ‘empowerment’ than previous studies suggest (De Graaf, Van Hulst, and Michels Citation2015; Van de Wetering and Kaulingfreks Citation2020; Stapper and Duyvendak Citation2020; Levine Citation2017). It thereby demonstrates that while a shift towards participatory approaches (Andersen and Van Kempen Citation2003; Tonkens and Verhoeven Citation2019) might be discursively present, practiced reality may be different. These insights contribute to the existing scholarship on citizen participation and active citizenship by underlining that these categories are not fixed, but rather continuously negotiated by those involved in participatory approaches.

Second, by applying an ethnographic approach, including document analysis, participant observation and interviews, this research makes a methodological contribution to the study of participatory governance. Whereas much research focuses on one of these methods of data collection, ethnography enables an integrated study of different layers of complex governance reality, thereby shedding light on how discursive and practiced realities interact and relate to one another.

Finally, this research demonstrates that in attempts to battle marginalisation and stigmatisation, existing ideas and assumptions about people and place are not simply exchanged, but rather reconsidered in practice. This insight provides a starting point for urban professionals’, and, more generally, local governments’, reflexivity: to challenge not only their perceptions of residents as ‘vulnerable’, but also the storyline of residents as ‘active citizens’. Such reflexivity could imply a move beyond discursive ideals of ‘active citizenship’ towards context-specific practices of participation in local neighbourhood policy.

This research has limitations, too, which provide directions for future work. First, while this research’s ethnographic and single case study approach enabled an in-depth analysis of the work of professionals, it leaves room to further explore the findings in other contextual settings. For instance, work could be done in other countries where a similar shift in the governance of urban marginality has taken place. Additionally, because this study took place in an unprecedented setting, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need for further investigation to understand this specific context in relation to others. Second, the explorative character of the current analysis asks for further research on the abductively developed concept of ‘selective empowerment’. Studies could engage with this concept by examining why some urban professionals might or might not be able or willing to take such an approach, or investigate the mechanisms through which ‘selective empowerment’ leads to residents feeling heard, and seeing their neighbourhoods improved.

Ethical approval

This research has been approved by the Ethical Review Board of Tilburg Law School, Tilburg University with #2019/26.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all of the respondents and to those who facilitated my field research. Thank you for sharing your stories, for providing me access to meetings and for connecting me to others. I am also grateful to those who provided constructive feedback on earlier drafts of this paper, especially at the 2021 Netherlands Institute of Governance, Critical and Interpretive Public Administration (NIG CIPA) paper sessions and the 2021 International Sociological Association Research Committee 21, Urban and Regional Development (ISA RC21) conference. Finally, I thank my supervisors and the two anonymous reviewers for their critical and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Agger, A., and A. Tortzen. 2022. “‘Co-Production on the inside’ – Public Professionals Negotiating Interaction Between Municipal Actors and Local Citizens.” Local Government Studies 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2081552.

- Alvesson, M., and D. Kärreman. 2007. “Constructing Mystery: Empirical Matters in Theory Development.” Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1265–1281. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586822.

- Andersen, H. T., and R. Van Kempen. 2003. “New Trends in Urban Policies in Europe: Evidence from the Netherlands and Denmark.” Cities 20 (2): 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(02)00116-6.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 18 (4): 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Bacqué, M., and C. Biewener. 2013. “L’empowerment, un nouveau vocabulaire pour parler de participation?” Idées économiques et sociales 3 (173): 25–32. https://doi.org/10.3917/idee.173.0025.

- Bakker, J., B. Denters, M. O. Vrielink, and P.-J. Klok. 2012. “Citizens’ Initiatives: How Local Governments Fill Their Facilitative Role.” Local Government Studies 38 (4): 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.698240.

- Bakker, W., H. Van der Reijden, V. Veraart, and R. Post. 2019. Leefbaarheid in Tilburg Resultaten enquête Lemon meting 2019. Amsterdam: RIGO Research en Advies.

- Bartels, K. P. R. 2018. “Collaborative Dynamics in Street Level Work: Working in and with Communities to Improve Relationships and Reduce Deprivation.” Environment & Planning C: Politics & Space 36 (7): 1319–1337. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418754387.

- Blijleven, W., M. Van Hulst, and F. Hendriks. 2019. “Public Servants in Innovative Democratic Governance.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovations and Governance, edited by S. Elstub and O. Escobar, 209–224. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862.00024.

- Boeije, H., and I. Bleijenbergh. 2019. Analyseren in Kwalitatief Onderzoek: Denken en Doen. Den Haag: Boom/Lemma.

- Brandsen, T. 2021. “Vulnerable Citizens: Will Co-Production Make a Difference?” In The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes, 527–539. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53705-0_27.

- Bredewold, F., J. W. Duyvendak, T. Kampen, E. Tonkens, and L. Verplanke. 2018. De Verhuizing van de Verzorgingsstaat, Hoe de Overheid Nabij Komt. Amsterdam: Van Gennep.

- De Graaf, L., M. Van Hulst, and A. Michels. 2015. “Enhancing Participation in Disadvantaged Urban Neighbourhoods.” Local Government Studies 41 (1): 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2014.908771.

- Dekker, K., and R. Van Kempen. 2004. “Urban Governance within the Big Cities Policy.” Cities 21 (2): 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2004.01.007.

- Dikeç, M. 2007. Badlands of the Republic, Space, Politics, and Urban Policy. Oxford: Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712788.

- Durose, C., and V. Lowndes. 2010. “Neighbourhood Governance: Contested Rationales within a Multi-Level Setting – a Study of Manchester.” Local Government Studies 36 (3): 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003931003730477.

- Durose, C., M. Van Hulst, S. Jeffares, O. Escobar, A. Agger, and L. De Graaf. 2016. “Five Ways to Make a Difference: Perceptions of Practitioners Working in Urban Neighborhoods.” Public Administration Review 76 (4): 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12502.

- Escobar, O. 2021. “Between Radical Aspirations and Pragmatic Challenges: Institutionalizing Participatory Governance in Scotland.” Critical Policy Studies 16 (2): 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1993290.

- Fung, A. 2004. Empowered Participation, Reinventing Urban Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Häikiö, L. 2012. “From Innovation to Convention: Legitimate Citizen Participation in Local Governance.” Local Government Studies 38 (4): 415–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.698241.

- Hajer, M. 2003. “Policy without Polity? Policy Analysis and the Institutional Void.” Policy Sciences 36 (2): 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024834510939.

- Hammond, M. 2021. “Democratic Innovations After the Post-Democratic Turn: Between Activation and Empowerment.” Critical Policy Studies 15 (2): 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2020.1733629.

- Hancock, L., and G. Mooney. 2013. ““Welfare ghettos” and the “Broken society”: Territorial Stigmatization in the Contemporary UK.” Housing, Theory & Society 30 (1): 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2012.683294.

- Herrting, N., and C. Kugelberg, eds. 2017. Local Participatory Governance and Representative Democracy, Institutional Dilemmas in European Cities. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315471174.

- Kampen, T., and E. Tonkens. 2019. “Empowerment and Disempowerment of Workfare Volunteers: A Diachronic Approach to Activation Policy in the Netherlands.” Social Policy & Society 18 (3): 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746418000143.

- Leidelmeijer, K., J. Frissen, and J. van Iersel. 2020. Veerkracht in het corporatiebezit. De update: een jaar later, twee jaar verder. In-Fact-Research & Circusvis. https://www.hetccv-woonoverlast.nl/doc/Update-veerkracht-in-het-corporatiebezit.pdf

- Levine, J. R. 2017. “The Paradox of Community Power: Cultural Processes and Elite Authority in Participatory Governance.” Social Forces 95 (3): 1155–1179. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow098.

- Lombard, M. 2013. “Citizen Participation in Urban Governance in the Context of Democratization: Evidence from Low-Income Neighbourhoods in Mexico.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 37 (1): 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01175.x.

- Lowndes, V., L. Pratchett, and G. Stoker. 2006. “Diagnosing and Remedying the Failings of Official Participation Schemes.” Social Policy & Society 5 (2): 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746405002988.

- Lupien, P. 2018. “Participatory Democracy and Ethnic Minorities: Opening Inclusive New Spaces or Reproducing Inequalities?” Democratization 25 (7): 1251–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1461841.

- Marcuse, G. E., and D. Cushman. 1982. “Ethnographies as Texts.” Annual Review of Anthropology 11 (1): 25–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.11.100182.000325.

- McMullin, C. 2022. ““I’m Paid to Do Other things”: Complementary Co-Production Tasks for Professionals.” Local Government Studies 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2077728.

- Michels, A. 2012. “Citizen Participation in Local Policy Making: Design and Democracy.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (4): 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.661301.

- Michels, A., and L. De Graaf. 2017. “Examining Citizen Participation: Local Participatory Policymaking and Democracy Revisited.” Local Government Studies 43 (6): 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1365712.

- Municipality of Tilburg. 2021. Wijken - Gemeente Tilburg. (z.d.). Gemeente Tilburg. Website https://www.tilburg.nl/stad-bestuur/stad/wijken/ (Last accessed April 2023).

- Musterd, S., and W. Ostendorf. 2023. “Urban Renewal Policies in the Netherlands in an Era of Changing Welfare Regimes.” Urban Research & Practice 16 (1): 92–108.

- Nussbaumer, J., and F. Moulaert. 2004. “Integrated Area Development and Social Innovation in European Cities.” City 8 (2): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000242201.

- PBL. 2016. De Verdeelde Triomf. Verkenning van stedelijk-economische ongelijkheid en opties voor beleid. Ruimtelijke Verkenningen 2016. Den Haag: Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving.

- Pierre, J. 2000. Debating Governance, Authority, Steering and Democracy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Provan, K. G., and P. N. Kenis. 2008. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 18 (2): 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum015.

- Riessman, C. K. 2005. “Narrative Analysis.“ Narrative, Memory & Everyday Life, edited byNancy Kelly, Christine Horrocks, Kate Milnes, Brian Roberts, David Robinson, 1–7. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

- Schatz, E., and E. Schatz, ed. 2009. Political Ethnography: What Immersion Contributes to the Study of Power. Chicago, IL:University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226736785.001.0001

- Somers, M. R. 1994. “The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach.” Theory & Society 23 (5): 605–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992905.

- Stapper, M., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2020. “Good Residents, Bad Residents: How Participatory Processes in Urban Redevelopment Privilege Entrepreneurial Citizens.” Cities 107 (August): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102898.

- Tahvilzadeh, N. 2015. “Understanding Participatory Governance Arrangements in Urban Politics: Idealist and Cynical Perspectives on the Politics of Citizen Dialogues in Göteborg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 8 (2): 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1050210.

- Tonkens, E., and I. Verhoeven. 2019. “The Civic Support Paradox: Fighting Unequal Participation in Deprived Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 56 (8): 1595–1610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018761536.

- Uitermark, J. 2014. “Integration and Control: The Governing of Urban Marginality in Western Europe.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 38 (4): 1418–1436. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12069.

- Uyterlinde, M., H. Boutellier, and F. De Meere. 2021. Perspectief Bieden: Bouwstenen voor de Gebiedsgerichte Aanpak van Leefbaarheid en Veiligheid in Kwetsbare Gebieden. Utrecht: Verwey-Jonker Instituut.

- Van der Velden, J., and E. Can. 2022. 75 Jaar Stedelijke Vernieuwing en Wijkaanpak: Kennisdossier Stedelijke Vernieuwing. The Hague: Platform 31. https://www.platform31.nl/artikelen/75-jaar-stedelijke-vernieuwing-en-wijkaanpak/

- Van de Wetering, S. A. L., and F. Kaulingfreks. 2020. “Youths Growing Up in the French Banlieues: Partners That Make the City.” In Partnerships for Livable Cities, edited by C. Montfort and A. Michels, 251–270. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40060-6_13.

- Van de Wijdeven, T., and F. Hendriks. 2009. “A Little Less Conversation, a Little More Action: Real-Life Expressions of Vital Citizenship in City Neighborhoods.” In City in Sight, Dutch Dealings with Urban Change, edited by J. W. Duyvendak, F. Hendriks, and M. van Niekerk, 121–140. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Van Kempen, R., and G. Bolt. 2009. “Social Cohesion, Social Mix, and Urban Policies in the Netherlands.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24 (4): 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-009-9161-1.

- Vanleene, D., J. Voets, and B. Verschuere. 2018. “The Co-Production of a Community: Engaging Citizens in Derelict Neighbourhoods.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations 29 (1): 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9903-8.

- Vanleene, D., J. Voets, and B. Verschuere. 2020. “The Co-Production of Public Value in Community Development: Can Street-Level Professionals Make a Difference?” International Review of Administrative Sciences 86 (3): 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318804040.

- Verhoeven, I., and E. Tonkens. 2013. “Talking Active Citizenship: Framing Welfare State Reform in England and the Netherlands.” Social Policy & Society 12 (3): 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746413000158.

- Verhoeven, I., and E. Tonkens. 2018. “Joining the Citizens: Forging New Collaborations Between Government and Citizens in Deprived Neighborhoods.” In From Austerity to Abundance? Creative Approaches to Coordinating the Common Good, edited by M. Stout. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2045-794420180000006008.

- Verhoeven, I., and E. Tonkens. 2022. “Enabling Civic Initiatives: Frontline Workers as Democratic Professionals in Amsterdam.” Local Government Studies 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2110077.

- Wacquant, L. 2007. “Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality.” Thesis Eleven 91 (1): 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513607082003.

- Wolcott, H. F. 1999. Ethnography: A Way of Seeing. Lanham, MD: Alta Mira Press.