ABSTRACT

Are national-level party political drivers of climate change performance reproduced locally? Here, I explore whether Greens’ ability to influence climate commitment nationally via legislative presence and coalition partnership is translated into English local government, using Climate Emergency gradings of local authority policy frameworks as the focus of comparative analysis. Scholarship on English local authority policy-making and performance suggests that, on balance, we should expect to see Green legislative presence and governing coalition effects translate to this level of government. While the finding of a positive Green legislative presence effect adds weight to the characterisation of local climate governance in England as a relatively collaborative process, the null finding on the coalition effect raises questions over the ability of junior coalition partners to realise preferences rapidly. Given the importance of sub-national politics to successful climate change transformation, it is vital that the factors associated with strengthened local commitment be further explored.

Introduction

While climate change is often thought of as a global challenge, it also remains very much an issue within which the local level plays a crucial role. In keeping with the profile of local governments within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) processes and elsewhere, significant scholarly attention has been placed on the sub-national foundations of climate change mitigation. Informed by broader scholarship on the foundations of effective local governance and policy performance (Lowndes and Leach Citation2004; Shaw Citation2012), studies have explored the institutional reforms involved in accelerating the local-level focus on climate change (Eckersley Citation2018; Lesnikowski et al. Citation2020; Porter, Demeritt, and Dessai Citation2015; Roberts Citation2008; Youm and Feiock Citation2019), and have critically evaluated the mitigation plans that have been made by local governments in a range of national contexts (Baker et al. Citation2012; Bulkeley and Kern Citation2006; Kuzemko and Britton Citation2020; Pearce and Cooper Citation2011; Qi et al. Citation2008; Reisinger et al. Citation2011). Through this paper, I advance scholarship on the local foundations of climate change governance by systematically incorporating a focus on the role of party politics. With much scholarship on party politics and climate change governance focusing on comparative national-level dynamics, I here explore whether these patterns are reproduced locally.

In analysing party politics and local climate change performance, I take advantage of Climate Emergency’s Council Plan scorecard, which offers an assessment of the strength of English local authorities’ climate change policy frameworks.Footnote1 We know from existing national-level comparative analysis that party politics can shape environmental policy performance and outcomes. There are, specifically, suggestions that Green electoral performance can shape environmental commitment, either by deploying influence through legislative processes (e.g., Debus and Tosun Citation2021), or through participation in coalition government (e.g., Knill, Debus, and Heichel Citation2010). I extend this scholarship on party politics and climate change policy frameworks by translating this predominantly nationally focused scholarship to the sub-national level.Footnote2

Existing scholarship on local government in England suggests that, on balance, we should expect to see the Green legislative presence and coalition participation effects translate down to this level of governance. Empirical results from this study confirm the former expectation and confound the latter. Through my analysis, Green representation in a local authority is found to exert a positive influence on the strength of local climate change policy frameworks, and no association is found between Green presence in a governing coalition and this outcome. The positive Green legislative influence effect suggests that decision-making in this area may be relatively collaborative and inclusive, with space for Green councillors to shape agendas and outcomes across local authority committees and governance processes. The Green coalition effect null finding may be shaped the rarity of Green coalition in English local authorities, and by potential time lags between presence and the delivery of reform. As well as offering new understanding of the foundations of effective climate governance in England, there is significant scope for the findings from this paper to be extended through further comparative analysis of sub-national climate performance, and wider exploration of Green influence ‘from the sidelines’.

In developing these central insights, the paper progresses through the following structure. In the first section below, I review scholarship on party politics and climate change performance, which directs our attention to Green legislative representation and coalition presence as potential mechanisms of influence on climate change commitment. I complement this review with a reflection on the nature of sub-national governance in England, which overall suggests we should expect legislative influence and the coalition presence effect to be translated to this level of governance. In the second section of the paper, I present an overview of the legislative and institutional contexts surrounding English local authority climate change action, before in the third and fourth sections, respectively, providing information about data selection and methodology, and a discussion of results. Through the conclusion, I return to the thematic extension offered through the finding of influence on policy performance from the sidelines of sub-national government, and reflect on the wider relevance of the study.

Party politics and local climate change performance: Expectations

At a foundational level, there are reasons to expect Green party representatives to display strong preferences in favour of climate change action. The Green party family is, in part, defined by its prioritisation of ecological issues (Burchell Citation2002, 3). In terms of national-level positioning, Carter (2009: 74) characterises the Green party family as ‘remarkably homogenous’ in its privilege of environmental and climate change concerns as a primary challenge of contemporary politics. While Greens have a strong tradition of de-centred governance, we nonetheless see this commitment carrying through to the local level (Gross and Jankowski Citation2020), with the party’s prioritisation of the environment and climate change serving as a core rationale for individuals becoming members and maintaining membership (Collignon et al. Citation2023). As a baseline, then, we can expect Green local political actor preferences to favour strengthened action on climate change.

Over the last decade or so, a prominent strand of scholarship has developed on the links between Green party presence and environmental policy and outcomes. Rihoux and Rüdig (Citation2006) sought to articulate a research agenda on Green party influence, calling for scholars to take note of and critically interrogate the Green electoral successes of the late 1990s and early 2000s that were said to have largely occurred ‘under the radar’ of academic analysis. However, Rihoux and Rüdig (12–20) were cautious about the extent to which we should expect to see Green's electoral success rapidly translate into outcomes, particularly given their low levels of governing experience and the need to go against the grain of existing orthodoxies to achieve core policy aims. Following on from Rihoux and Rüdig, further studies have explored mechanisms through which Greens has exercised influence over policy outcomes. Broadly, we see evidence of Green's influence being exerted from presence in legislatures, and from the position of coalition partnership.

In terms of Green's legislative presence, studies support the idea that representation in the chamber may, in itself, be associated with strengthened environmental and climate change commitments. A range of contributions offer national-level case study explorations of such Green influence across Europe (Muller-Rommel Citation2002; Rootes Citation2002; Rüdig Citation2002; Spoon Citation2009), and beyond (Bale and Dann Citation2002). Quantitatively oriented studies of the topic have also probed the existence of systematic influence from Green's legislative presence. Neumayer (2003) offers a partial insight into the positive role of Green representation on national-level environmental commitment. Focusing on OECD states from 1980 to 1999, Neumayer found that the combined parliamentary strength of Green and left-libertarian parties impacted positively on air quality indicators. At the national level, then, Green's legislative presence may have shaped environmental outcomes by, for example, using contributions to debates and committee processes to push for strengthened policy positions and goals.

Additional light is shed on the potential mechanics of this legislative mechanism of Green influence by Debus and Tosun (Citation2021), who are specifically interested in the contributions made to national-level parliamentary debates. Through a comparative analysis of national parliamentary debates across five European countries in the mid-2000s, Debus and Tosun (933) conclude overall ‘that it is the presence of Green parties in parliaments that determines to what degree the … green agenda is placed on the legislative agenda’. Greens, then, are shown to be able to meaningfully impact the scope of coverage of parliamentary debates, although the subsequent policy impact from this mechanism of discursive influence remains unexplored here.Footnote3 Folke’s (Citation2014) study of the impact from Green representation on the strength of Swedish municipal authorities’ environmental policy does take this additional step to consider the links between Green's legislative presence and outcomes. Using a magazine survey-based measure of environmental policy performance, Folke finds additional Green representation to be associated with improved environmental commitment. Folke suggests that this dynamic may likely be limited to governance systems using proportional representation, which tend more heavily towards inter-party partnership and cooperation.

We can see, then, some evidence of Green's influence on climate change or environmental policy commitment being generated through a legislative presence. To what extent, though, would we expect this tendency to be carried over into English local government? The prevalence of ‘leader and cabinet’ governance structures, which local authorities moved towards following the UK Local Government Act (2000), may present an impediment to this form of legislative influence. Compared to committee-based systems, the leader and cabinet model sees decision-making power being formally concentrated in the hands of a small number of executive councillors. However, while these governance structures have been criticised for creating conditions for ‘fiefdom’-based governance in which smaller parties and independent councillors can effectively be frozen out (Palese 2022: 19), Lowndes and Leach (Citation2004) and Dacombe (Citation2011) highlight the persistence of local variation in the inclusiveness of governance processes. Within this pattern of local variation, LGA (Citation2022, 15) surveys of councillors provides a useful overarching source of insight, with two-thirds of responding councillors giving a positive assessment of their own ability to exert influence.Footnote4 Moreover, Coulson and Whiteman (Citation2012, 187) provide a positive assessment of councillors’ ability to exert influence over policy through committee structures and governance processes. Pitt and Congreve (Citation2017), focusing specifically on climate change governance and Climate Action Plan preparation, suggest that across their five English local authority case study areas a relatively high level of collaborative decision-making was displayed.

English local authorities may, then, contain features that constrain the potential for councillor impact and influence. However, on balance, I take existing scholarship on Green party legislative presence effects, and existing characterisations of councillor influence in English local government, to generate an expectation that Green councillors will be able to use their presence in committees and governance processes to shape climate change commitment. Consequently, I present the following hypothesis to be tested empirically:

H1:

Green legislative presence will be positively associated with the strength of a local authority’s climate change policy framework.

At a theoretical level, we can expect participation in a governing coalition by a minor party to present an opportunity to exercise influence (Callen and Roos Citation1977). Indeed, a national-level comparative analysis from Bäck et al. (Citation2009) shows that minor parties are often able to capture a disproportionately large number of cabinet positions, suggesting that coalition formation may catalyse significant opportunities for influence.Footnote5 As we move from this overarching scholarship on coalition minor party influence to studies that have focused specifically on the impact on policy outcomes from the Green coalition presence, we see in general that this theoretical capacity to exert influence through coalition presence is translated into reality.

Röth and Schwander (Citation2020) present a national-level analysis of the Green coalition's impact on welfare policies across the OECD from the 1970s to 2015. The underlying intuition is that, while not at the top of the party’s agenda, Greens typically advocate progressive welfare policies, and so we should expect to see the Green coalition's presence having a positive impact on such outcomes. This study provides a partial confirmation of this expected effect. Specifically, while no systematic relationship was found between the Green coalition’s presence and the overall level of national social spending, evidence is presented of a positive association with strengthened ‘social investment’ policies. While the Green coalition's presence was not found to increase overall welfare spending, it was found to contribute to more active labour market policies and stronger provision of early years care that may enhance populations’ capacity to enter the labour market.

While Röth and Schwander did not test for the Green coalition's influence on environmental performance, Knill et al (Citation2010) do explore this dimension. Knill et al specifically sought to explain variations in the aggregate number of national-level environmental protection measures put in place across OECD countries from 1970 to 2010. While probing the influence of a range of political and institutional factors on performance in this regard, Knill et al. include a dummy variable to control for the presence of a Green or left-libertarian coalition partner. Evidence is presented that the presence of such a coalition partner is associated with a higher number of environmental policy adoptions (Knill, Debus, and Heichel Citation2010, 325).

Should we expect this pattern of Green coalition influence to be translated into English local government? At a general level, we know that governing party control matters in shaping a range of outcomes in English local government. Clegg and Farstad (Citation2021), for example, have shown that left-wing local authority control is systematically associated with an increased use of Section 106 planning powers to extract funding from developers for additional social housing. And, as noted above, the move towards leader and cabinet governance has served to consolidate the relative control enjoyed by executive councillors. As such, scholarship on the Green coalition effect and on executive leadership in English local politics broadly suggests that we should expect the Green coalition's presence at this level to translate into a strengthened climate commitment. Consequently, I present the following hypothesis to be tested empirically:

H2:

Green coalition presence will be positively associated with the strength of a local authority’s climate change policy framework.

Before laying the foundations for the empirics Iuse to test these hypotheses, below Ifirst provide acontextualisation of the role of English local government in addressing climate change.

Local government and climate change in England

Across England, there is significant variation in the structure of local government. There are currently 326 local authority units, structured either as District Councils with overarching County Councils, Unitary Authorities, Metropolitan Districts, and London Boroughs.Footnote6 While their form and function differ, shared competencies over transport and planning policy, and their roles as large energy consumers provide potentially potent tools for advancing climate change policy and performance. Cooper and Pearce (Citation2011, 1098) identify three pathways through which authorities can act as local climate change leaders. As estate managers, they can use their control over energy use, staff transport, procurement, and investment. As service providers, they can use their control over waste management, transport and infrastructure planning, enforcing efficiency standards, and influence over schools and care homes. As community leaders, they can work to shape local populations’ and businesses’ behaviour in more environmentally sustainable directions.

In the UK, the Westminster government's climate commitments provide the overarching framework within which local authority climate agendas have developed. The 1997 Kyoto Agreement provided an important moment in the development of the UK's approach to climate change, functioning as an occasion at which, alongside many other states, a commitment was made to implement policies to reduce harmful emissions. Following the government’s ratification of the Agreement, in 2000 its Climate Change Programme sought to outline measures to support carbon reduction of 20% by 2020 (against a 1990 baseline). In 2008, the Climate Change Act served to further strengthen the Westminster government’s commitments, increasing the scale of ambition and establishing the Committee on Climate Change to assess government performance and provide policy advice. The Act created the first legally-binding climate change target, with the UK government having to take action to achieve an 80% reduction by 2050. In a recent assessment, the Committee on Climate Change (Citation2020, 7) recommended that ‘major policy strengthening’ was required to achieve future targets, outlining necessary adjustments in the areas of transport, housing, waste management, and elsewhere.

Local authorities have been characterised as enjoying ‘partial autonomy’ from the central government, both in general and specifically on environmental policy. Westminster provides overarching expectations and parameters, leaving local authorities with space for flexible experimentation (Wilson and Game Citation2002). In relation to climate change, there is no explicit statutory obligation on local government to address the issue. However, in the Climate Change Programme authorities were positioned as ‘critical to the delivery of … the action needed on the ground to cut emissions’ (DETR Citation2000, 40). While individual initiatives drew on local authorities as implementing agents, such as the Energy Saving Trust’s home insulation grant scheme, central government relied heavily on information dissemination as a tool to support shifts in local authority behaviour and policies. Sharing advice on available mitigation and adaptation strategies has been a primary pillar of Westminster support (Demeritt and Langdon Citation2004). From the mid-2000s, central government worked to construct a monitoring regime to nudge authorities towards enhanced climate action. Under the (NAO Citation2007), local authorities were required to report data annually on outcomes including CO2 emissions reductions and the status of their climate change plans. In their evaluation of the New Performance Framework, Cooper and Pearce (Citation2011) find evidence of the initiative having helped move climate change up local authorities’ agendas. In a broader review, Bache et al. (Citation2015) report frustrations from sub-national government at the ‘fuzziness’ of central government climate change guidance, and a desire in some quarters for more robust statutory frameworks and expectations.

Within this national policy constellation, there is evidence of notable variation in local authorities’ use of their autonomy in the realm of climate policy. In October 2000, a group of local authority senior leaders met to discuss ways of supporting the emergent climate change agenda. A result of the conference was the Nottingham Declaration; a pledge that was open for local authority leaders to sign, demonstrating their prioritisation of climate change and committing to developing an authority-level Climate Change Action Plan within 2 years of signing-up. The Declaration, and the associated best-practice sharing through the Declaration Development Group, functioned as a tool to assist climate change pioneers in individual authorities to advance their agenda. The voluntary nature of the initiative, however, led to delayed engagement from many authorities; a small group of local authority climate change leaders signed-up at the launch of the Declaration, with further pledges remaining ‘slow but steady’. By the late-2000s around half of local authorities had become signatories (Gearty Citation2008, 85; Nottingham Declaration Partnership Citation2010, 1).

Additional evidence of variation in authorities’ engagement with climate change comes from evaluations of local government from the Green Alliance and from the Climate Change Committee. The Green Alliance (Citation2011: 2) surveyed local authorities on the status of their green commitments as austerity cuts to funding from central government began to bite, finding clear divisions between around one-third of authorities who anticipated that their current levels of mitigation would continue or increase, one-third who anticipated a marginal narrowing and one-third who anticipated a significant de-prioritisation. Committee on Climate Change (Citation2012, 69–71) suggest that variation in engagement with mitigation efforts was being driven by a range of factors, including political will and financial pressures. Subsequent studies continue to point to the existence of climate change leaders and laggards across local authorities (e.g., Friends of the Earth Citation2019). In 2021, Climate Emergency (a UK civil society organisation) launched a scorecard project to systematically evaluate the strength of local authority climate change policy frameworks. As is explored below, the Climate Emergency scorecard revealed wide variation in the strength of local authorities’ climate change policy frameworks; while a handful of authorities attained scores of 80% or higher within the Climate Emergency assessment, the mean score was below 50 and many authorities were found to have no Climate Action Plan in place. The empirical focus of this paper is on exploring in particular the role of local party politics as a driver of this wide variation in climate change performance across English local authorities.

Data and methodology

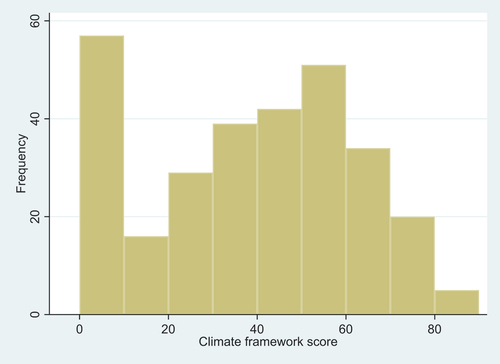

For the outcome variable of local authority climate change policy framework strength, I use Climate Emergency Action Plan scorecard data. Assessments of publicly available action plans listed on local authority webpages as of June 2021 were conducted by Climate Emergency, with 324 English local authorities included in the exercise. An overall composite grade was created by evaluating publicly available Climate Action Plans against the following criteria (weightings noted in parentheses): governance and funding (15%), mitigation and adaption (15), integration (15), community engagement (15), measuring and setting emissions targets (10), social inclusion (10), education, and training (10), climate emergency declaration (5), emphasis on co-benefits from climate action (5). Where a local authority did not have a Climate Action Plan, scores of zero were given across all dimensions. In total, 59 local authorities were given scores of zero.Footnote7 This reliance on local authority supplied Climate Action Plan documentation to assess the strength of governance frameworks means that the outcome variable does not shed light on policy outcomes and outputs more generally. Given that councils will find it easier to craft improved climate change-related documentation than to generate improved climate change-related outcomes, this outcome variable specification can be seen to present a softer test of Green influence.

For the measure of Green's legislative presence used to probe H1, I turned to Keith Edkins’ Local Council Political Compositions data. Edkins has included information on the number of Green councillors since 2006. To navigate potential time lags between legislative presence and changes to published Climate Action Plans, I again create specifications that capture whether a given council had included Green representation within 2006–19, 2006–18, and 2006–17. In each case, the variable was coded 1 where there had been a Green legislative presence within the relevant period and 0 otherwise. These specifications represent an exacting operationalisation, given that we end up including authorities with just 1 year of Green representation from 2006 through to 2017/18/19 as positive cases of Green's legislative presence.Footnote8

Information on the Green party coalition's presence in English local government is not included in either The Election Centre or Open Council databases, the main sources for comparative political analysis of UK local authorities. Therefore, to operationalise H2 and probe the relationship between Green coalition presence and local climate change policy framework strength, I again turned to Edkins’ Local Council Political Compositions archive.Footnote9 Edkins provides data on the political make-up of each local authority and has since 2006 included data on coalition composition. Given the cancellation of local elections in 2020 and the proximity of May 2021 elections to the June 2021 Climate Emergency census date (which would mean that changes to local political compositions would have no opportunity to filter through into new or amended Climate Action Plans), the latest Green coalition observations are from 2019. From Edkins’ data, I created a dummy variable ‘Green coalition’ coded 1 where there had been Green presence in a coalition administration within the period 2006–19 and 0 otherwise.Footnote10 There are likely to be moderate time lags between this independent variable and the outcome variable; it may, for example, plausibly be the case that a Green coalition coming to power in 2019 would not have sufficient time to achieve the ratification of a new or substantially altered Climate Action Plan by the census date of June 2021. To test for the possible existence of such lags, I run alternative specifications of the coalition presence dummy to capture only cases where there had been a Green coalition in the periods 2006–18 and 2006–17. The intuition here is that, if a Green coalition had been formed in 2017, sufficient time should have passed by summer 2021 for preferences to be incorporated into the framework documents.Footnote11

I include two additional control variables within the model. In the light of longstanding debates over the relationship between income and environmental outcomes (e.g., Chen and Chen Citation2008; Magnani Citation2000; McConnell Citation1997), I included Climate Emergency’s local authority income quintile score within the empirical analysis. This source was ultimately derived from the Office for National Statistics Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings.Footnote12 Finally, to control for the possibility that local authority performance varies according to governance structure, I created dummy variables to capture whether an authority was a Unitary Authority, London Borough, Metropolitan District, or a two-tier District with County Council structure.

Results and discussion

There are a total of 326 local authorities in England. Owing to missing data,Footnote13 293 cases were available for analysis. As shown in , across these English local authorities there was significant variation in Climate Emergency scores. Manchester City Council and Staffordshire Moorlands District Council were the strongest performers, with scores of 87. Conversely, 57 councils attained a score of 0, by virtue of not having adopted a Climate Action Plan.Footnote14 The mean score across all councils was 37. provides additional detail on the distribution of authorities’ climate framework scores. Once we move past the large tail of councils that achieved a score of zero, we see that scores broadly follow a normal distribution.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Turning to the measures of Green influence we see that, from 2006 to 19, just nine councils had experienced a Green coalition administration. The equivalent figures across 2006–18 and 2006–17 were six and five, showing the historic rarity of this condition within English local government. During the 2006–19 period, we see that 144 councils – around 44% – had experienced Green legislative representation. Given the extent of Green's success in the 2019 local election cycle, the equivalent figures for 2006–18 and 2006–17 are notably lower, with 81 and 72 authorities having experienced Green representation in these respective periods. In terms of the control variables, from the income measure we see a relatively even distribution across income quintiles. Finally, within the sample, we have 46 Unitary Authorities, 26 London Boroughs, and 34 Metropolitan Boroughs. This leaves the 106 two-level County and District authorities providing the baseline for the model.

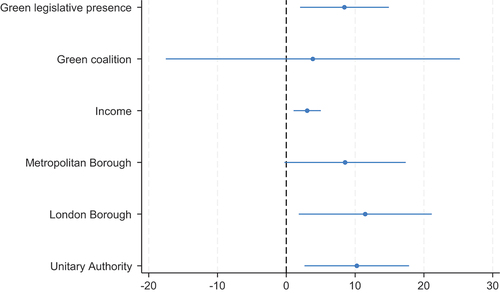

The results of the OLS regressions are displayed in . Through Model 1, I deploy the 2006–17 specifications of the variables of primary interest. Overall, we see that Model 1 (2006–17) is significant (p < 0.001), explaining around 9% of the observed variation in local authority performance (χ2=.091). Models 2 and 3 focus on the 2006–18 and 2006–19 specifications, and display similar explanatory power. Given the complexity of climate change performance and the wide array of factors involved, the explanatory power of the models is moderately high. Findings are similar across the three models, and an overview of Model 1 marginal effects is displayed below in .

Figure 2. Average marginal effects on climate framework strength with 95% confidence intervals (Model 1).

Table 2. Explaining local authority variation in climate framework strength.

Under the initial Model 1 specification, we see that Green legislative presence in a council’s legislature between 2006 and 17 is associated with a boost to the Climate Action Plan score of around 8 points. While the overall finding was expected and gives a confirmation of the relationship between Green's legislative presence and climate framework strength as articulated through H1, the scale of the effect is notable. This finding is particularly interesting given the relatively tough test provided by the variable specification, which includes councils as positive cases regardless of the number of Green representatives or the number of years for which Greens were sitting. The continued significance of the Green legislative representation effect through the 2006–18 and 2006–19 specifications provides reassurance on the robustness of this finding. It seems that Green councillors are likely to be able to accelerate the focus on climate change within their councils through activity on scrutiny committees, contributions to debate, responses to consultations, or other mechanisms of local influence.

In contrast to this confirmation of H1 on the Green legislative presence effect, when we turn to the Green coalition presence effect we see that results confound H2. The presence of Greens in a coalition seems not to exert significant influence on the strength of councils’ climate frameworks. This null finding on the coalition presence effect holds across the Model 2 (2006–18) and Model 3 (2006–19) specifications.Footnote15 It seems that the small number of Green coalition partners have not been able to systematically improve climate performance in their local authority areas.Footnote16

Beyond this confounding of H1 and confirmation of H2, the empirical findings highlight additional statistically significant determinants of local authority climate framework strength. Model 1 (2006–17), Model 2 (2006–18), and Model 3 (2006–19) all report a positive relationship between income and climate framework strength, suggesting that the better-off a local authority area, the stronger its climate change policy framework. This matches with expectations relating to the environmental Kuznets curve, and the intuition that more affluent areas may at the margins have better-funded authorities with more institutional capacity to craft strong Climate Action Plans. Across Models 1 to 3, we consistently see that local authority type has a significant effect on climate framework strength. Specifically, Unitary Authorities, London Boroughs, and Metropolitan Boroughs all perform more strongly than the baseline provided by the two-level County and District Councils. Additional investigation is required to explore whether differential performance is largely driven by local authority types’ differing policy responsibilities or whether the two-level County and District Councils may have systematically weaker capacity to create required policy frameworks and therefore are in need of additional capacity-building support.

Conclusion

Local government is a vital pillar in overall efforts to combat climate change. Globally, the UNFCCC has long recognised the central role played by sub-national political structures in translating overarching targets into on-the-ground achievements. Domestically within the UK, since the launch in 2000 of the Westminster government’s Climate Change Programme, local authorities’ importance in reaching climate change targets has been regularly acknowledged.

In line with climate change's critical role in local government, previous studies have sought to extend our understanding of the determinants of commitment and effectiveness. While valuable insights have been gained from analyses of the comparative legislative and regulatory powers of local government and of the prioritisations contained within climate action plans (Baker et al. Citation2012; Bulkeley and Kern Citation2006; Porter, Demeritt, and Dessai Citation2015; Qi et al. Citation2008; Reisinger et al. Citation2011; Roberts Citation2008), there has been relatively little systematic analysis of the party political determinants of variation in sub-national climate performance.

Existing national-level scholarship on the party's political drivers of variation in climate performance pointed to the potential importance of the Green legislative presence and coalition partnership. My translation of this national-level focus on party politics and climate performance to the local level represents an extension to this existing scholarship. Through this analysis, I have probed empirically the influence from these party political factors on the strength of English local authority climate change frameworks. Green legislative representation was found to be associated with improved local performance; as such, it seems that influence from the sidelines of local government may provide an important mechanism through which Greens are able to translate preferences into outputs. No evidence was found of the Green coalition's presence being associated with improved climate policy framework strength, suggesting that the small number of Green coalition partners in English local government have not been able to systematically strengthen climate frameworks in their areas across the time-frame examined.

Features of English local government make this a challenging case in which to test for the Green legislative presence and coalition partnership effects. The reliance of English local authorities on ‘winner takes it all’ plurality voting provides an institutional context that tends towards single-party control, which can have the effect of both creating governing cultures and processes that exclude representatives of smaller parties and independents and limiting the space for coalition formation. Additionally, the Green party has enjoyed limited electoral success in English local elections, which again is likely to have limited the scope for positive influence to be exerted on climate change commitment. Consequently, the fact that a Green legislative presence effect has been found in English local government would lead us to expect to see this dynamic reproduced, particularly across European states that may have stronger performing Green parties and may use proportional representation electoral systems that tend towards inter-party collaboration. We could also more plausibly expect to see evidence of positive Green coalition effects across these alternative contexts.

Across the UK, while local authorities’ near-universal issuance of Climate Emergency Declarations signals commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation, there is wide variation in the strength of climate change policy frameworks. Throughout this paper, I have offered insights into party political drivers of variation in the effectiveness with which local authorities are meeting these climate change challenges. In the UK and beyond, subnational politics constitutes an important site for climate change action; to build foundations for improved collective performance, greater understanding is needed of the drivers of variation in commitment and effectiveness.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (27.5 KB)Acknowledgement

Liam Clegg stood as a Green party candidate in the English local elections, May 2023. Institutional guidance was to declare this candidacy within peer review and publications, to support the integrity of research processes and outputs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2023.2292662

Notes

1. Climate Emergency is a UK civil society organisation. In summer 2021, a team of 120 Climate Emergency researchers systematically scored local authorities’ published Climate Action Plans, evaluating dimensions including the robustness of governance and funding regimes laid out, the scale of mitigations and adaptations, and the inclusion of emissions targets and monitoring frameworks. Further information is provided in ‘Data and Methodology’, below.

2. As noted below, Folke’s (Citation2014) study of Swedish municipalities provides an example of scholarship exploring Green party politics and local environmental policy. By focusing specifically on climate change policy frameworks rather than more generally on environmental policy, and by exploring the effect of legislative presence and coalition partnership, I offer thematic extensions to this work.

3. Abou-Chadi’s (Citation2016) study suggests that inter-party competition may provide an additional route pathway for Green influence, with mainstream parties potentially responding to Green success by adopting a more prominent commitment to environmental issues in the subsequent election. Owing to the structure of the empirical model and focus on policy framework strength rather than manifesto commitments, it was not possible to probe this potential line of influence.

4. As denoted by survey responses ‘More influence to change things than expected’ or ‘As much influence to change things as expected’.

5. For a focus on the politics of subnational coalition formation, see Back (Citation2003) and Debus and Gross (Citation2016).

6. See Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government official website, available at https://www.gov.uk/guidance/local-government-structure-and-elections. Accessed 17th June, 2021. See also Clegg (Citation2021) for additional overview.

7. The Climate Emergency council scorecard involved a team of 120 researchers assessing the effectiveness of dimensions of local authority Climate Action Plans including the outlined governance and funding frameworks, mitigation and adaptation strategies, integration of climate priorities across the council’s operations, community engagement, the measurement and setting of emissions targets, and whether an authority had declared a climate or ecological emergency. Coding was guided by a 60-page checklist to ensure comparability of evaluations, with a second stage in the process integrating a ‘right to reply’ and expert calibration. While the use of non-anonymised documentation within the grading exercise introduces possibility for researcher bias, overall the Climate Emergency data provides a useful tool with which to operationalise the climate change commitment variable. Climate Emergency data is used in Garvey et al’s (Citation2023) study of local authority climate change commitment and capacity. See ‘Methodology’, Climate Emergency website, available at https://councilclimatescorecards.uk/plan-scorecards-2022/methodology/. Accessed 20th February, 2023.

8. To test for the possible cumulative effect of Green legislative presence, I also created a parallel measure that followed the parameters noted in the footnote above.

9. See ‘Political Compositions’ pages of Keith Edkins website, available at https://www.theedkins.co.uk/uklocalgov/makeup.htm. Accessed 22nd July, 2022.

10. Edkins identifies a local authority as having a Green coalition partner where there is a known public declaration of such a governing arrangement.

11. To test for the possible cumulative effect of Green coalition presence, I also created a parallel measure that captured the number of years of Green coalition presence across each of the timeframes of interest (i.e., for an authority that had just one year of Green coalition a value of 1 was given, for four years a value of 4, and so on).

12. See ONS official website, available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/placeofresidencebylocalauthorityashetable8. Accessed 23rd June, 2021.

13. Climate Emergency score are available for 324 local authorities; gaps in The Election Centre coverage on council compositions and formatting incompatibilities across some case observation years were the main sources of missing data.

14. In theory, the maximum score attainable under the Climate Emergency scorecard would be a grade of 100.

15. To probe the potential cumulative influence from the party political factors of interest on the outcome variable, I re-ran the models employing specifications that captured the total number of years in which there was Green legislative presence and coalition partnership. Under these cumulative measures, no significant relationships were found. Consequently, it seems that it is the existence of any Green legislative presence, rather than the cumulative legislative presence, that influences the strength of climate change policy frameworks.

16. As an extension of the model, I ran versions that incorporated a measure of left-wing control with a dummy variable capturing observations where there had been at least one year of Labour majority control (in the UK context, Labour is conventionally held to represent the more left-wing of the three mainstream parties). The rationale behind this extension comes from debates over the presence of a left-wing partisan orientation effect on climate change commitment in other contexts (cf. Schultze 2014, Carter and Clements Citation2015, Tobin 2017; Farstad Citation2018; Farstad Citation2019).This variable was operationalised using Edkins’ Local Council Political Composition database. Reflecting the parameters used when operationalising the Green legislative presence and coalition partnership variables, I ran models with three dummy variables capturing labour control in the periods 2006–17, 2006–18, and 2006–19. With this measure, left-wing orientation was found to not exert a significant influence on climate change commitment. The inclusion of the left-wing control variable did not significantly alter the results from Models 1–3, as reported in and . It should be noted that this operationalisation of left-wing control represents a sub-optimal intervention: cases in which there had been a period of Labour control and a period of Green coalition presence across the given time period will be identified as both displaying Labour control and Green coalition presence, meaning that the models are not capturing the independent influence from these factors.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T. 2016. “Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts – How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (2): 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000155.

- Alliance, G. 2011. Is Localism Delivering for Climate Change? London: Green Alliance.

- Bache, I., I., Bartle, M. Flinders, and G. Marsden. 2015. “Blame Games and Climate Change: Accountability, Multi-Level Governance and Carbon Management.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 17 (1): 64–88.

- Bäck, H. 2003. “Explaining and Predicting Coalition Outcomes: Conclusions from Studying Data on Local Coalitions.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (4): 441–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00092.

- Bäck, H., H. Meier, and T. Persson. 2009. “Party Size and Portfolio Payoffs: The Proportional Allocation of Ministerial Posts in Coalition Governments.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 15 (1): 10–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330802666760.

- Baker, I., A. Peterson, G. Brown, and C. McAlpine. 2012. “Local Government Response to the Impacts of Climate Change: An Evaluation of Local Climate Adaptation Plans.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107 (2): 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.009.

- Bale, T., and C. Dann. 2002. “Is the Grass Really Greener? The Rationale and Reality of Support Party Status: A New Zealand Case Study.” Party Politics 8 (3): 349–365.

- Bulkeley, H., and K. Kern. 2006. “Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK.” Urban Studies 43 (12): 2237–2259. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600936491.

- Burchell, J. 2002. The Evolution of Green Politics. London: Routledge).

- Callen, J., and L. Roos. 1977. “Political Coalition Bargaining Behaviour.” Public Choice 32 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01718666.

- Carter, N., and B. Clements. 2015. “From “Greenest Government ever” to “Get Rid of All the Green crap”: David Cameron, the Conservatives and the Environment.” British Politics 10 (2): 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2015.16.

- Chen, C., and Y. Chen. 2008. “Income Effect or Policy Result: A Test of the Environmental Kuznets Curve.” Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (1): 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.07.027.

- Clegg, L. 2021. “Taking One for the Team: Partisan Alignment and Planning Outcomes in England.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (4): 680–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120985409.

- Clegg, L., and F. Farstad. 2021. “The Local Political Economy of the Regulatory State: Governing Affordable Housing in England.” Regulation & Governance 15 (1): 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12276.

- Collignon, S., W. Rüdig, C. Lamprinakou, I. Makropoulos, and J. Sajuria. 2023. “Intertwined Fates? Members Switching Between Niche and Mainstream Parties.” Party Politics 29 (5): 840–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221106299.

- Committee on Climate Change. 2012. How Local Authorities Can Reduce Emissions and Manage Climate Risk. London: Committee on Climate Change.

- Committee on Climate Change. 2020. Policies for the Sixth Carbon Budget and Net Zero. London: Committee on Climate Change.

- Cooper, S., and G. Pearce. 2011. “Climate Change Performance Measurement, Control and Accountability in English Local Authority Areas.” Accounting, Auditing, and Accountability 24 (8): 1098–1118. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571111184779.

- Coulson, A., and P. Whiteman. 2012. “Holding Politicians to Account? Overview and Scrutiny in English Local Government.” Public Money & Management 32 (3): 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2012.676275.

- Dacombe, R. 2011. “Who Leads? Councillor‐Officer Relations in Local Government Overview and Scrutiny Committees in England and Wales.” International Journal of Leadership in Public Services 7 (3): 218–228.

- Debus, M., and M. Gross. 2016. “Coalition Formation at the Local Level: Institutional Constraints, Party Policy Conflict, and Office-Seeking Political Parties.” Party Politics 22 (6): 835–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815576292.

- Debus, M., and J. Tosun. 2021. “The Manifestation of the Green Agenda: A Comparative Analysis of Parliamentary Debates.” Environmental Politics 30 (6): 918–937.

- Demeritt, D., and D. Langdon. 2004. “The UK Climate Change Programme and Communication with Local Authorities.” Global Environmental Change 14 (4): 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.06.003.

- DETR. 2000. Climate Change: The UK Programme. London: Department for Environment, Transport, and the Regions.

- Eckersley, P. 2018. “Who Shapes Local Climate Policy? Unpicking Governance Arrangements in English and German Cities.” Environmental Politics 27 (1): 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1380963.

- Farstad, F. 2018. “What explains variation in parties’ climate change salience?” Party Politics 24 (6): 698–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817693473.

- Farstad, F. 2019. “Does Size Matter? Comparing the Party Politics of Climate Change in Australia and Norway.” Environmental Politics 28 (6): 997–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1625146.

- Folke, O. 2014. “Shades of Brown and Green: Party Effects in Proportional Election Systems.” Journal of the European Economic Association 12 (5): 1361–1395. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12103.

- Friends of the Earth. 2019. Performance on Climate Change by Local Authorities in England and Wales. London: Friends of the Earth.

- Garvey, A., M. Büchs, J. Norman, and J. Barrett. 2023. “Climate Ambition and Respective Capabilities: Are England’s Local Emissions Targets Spatially Just?” Climate Policy 23 (8): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2208089.

- Gearty, M. 2008. “Achieving Carbon Reduction: Learning from Stories of Vision, Chance, and Determination.” The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 30 (1): 81–94. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2008.su.00007.

- Gross, M., and M. Jankowski. 2020. “Dimensions of Political Conflict and Party Positions in Multi-Level Democracies: Evidence from the Local Manifesto Project.” West European Politics 43 (1): 74–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1602816.

- Knill, C., M. Debus, and S. Heichel. 2010. “Do Parties Matter in Internationalised Policy Areas? The Impact of Political Parties on Environmental Policy Outputs in 18 OECD Countries, 1970–2000.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (3): 301–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01903.x.

- Kuzemko, C., and J. Britton. 2020. “Policy, Politics and Materiality Across Scales: A Framework for Understanding Local Government Sustainable Energy Capacity Applied in England.” Energy Research & Social Science 62 (10): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101367.

- Lesnikowski, A., R. Biesbroek, J. Ford, and L. L. Berrang-Ford. 2020. “Policy Implementation Styles and Local Governments: The Case of Climate Change Adaptation.” Environmental Politics 30 (5): 1–38. OnlineFirst. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1814045.

- LGA. 2022. National Census of Local Authority Councillors. London: Local Government Association).

- Lowndes, V., and S. Leach. 2004. “Understanding Local Political Leadership: Constitutions, Contexts and Capabilities.” Local Government Studies 30 (4): 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300393042000333863.

- Magnani, E. 2000. “The Environmental Kuznets Curve, environmental protection policy and income distribution.” Ecological Economics 32 (3): 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00115-9.

- McConnell, K. 1997. “Income and the Demand for Environmental Quality.” Environment and Development Economics 2 (4): 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X9700020X.

- Muller-Rommel, F. 2002. Green Parties in National Governments, edited by T Poguntke. London: Routledge).

- NAO. 2007. Central Government Support for Local Authorities on Climate Change. London: National Audit Office.

- Nottingham Declaration Partnership. 2010. “Nottingham Declaration Partnership: Next Steps.” Local Government Association Environment Board Paper, May, 27: 1–4.

- Pearce, G., and S. Cooper. 2011. “Sub-National Responses to Climate Change in England: Evidence from Local Area Agreements.” Local Government Studies 37 (2): 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2011.554825.

- Pitt, D., and A. Congreve. 2017. “Collaborative Approaches to Local Climate Change and Clean Energy Initiatives in the USA and England.” Local Environment 22 (9): 1124–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1120277.

- Porter, J., D. Demeritt, and S. Dessai. 2015. “The Right Stuff? Informing Adaptation to Climate Change in British Local Government.” Global Environmental Change 35 (2): 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.10.004.

- Qi, Y., L. Ma, H. Zhang, and H. Li. 2008. “Translating a Global Issue into Local Priority: China’s Local Government Response to Climate Change.” Journal of Environment & Development 17 (4): 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496508326123.

- Reisinger, A., D. Wratt, S. Allan, and H. Larsen. 2011. “The Role of Local Government in Adapting to Climate Change: Lessons from New Zealand.” In Climate Change Adaptation in Developed Nations, edited by J. Ford and L. Berrang-Ford, 303–319. London: Springer.

- Rihoux, B., and W. Rüdig. 2006. “Analyzing Greens in Power: Setting the Agenda.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (1): 1–33.

- Roberts, D. 2008. “Thinking Globally, Acting Locally—Institutionalizing Climate Change at the Local Government Level in Durban, South Africa.” Environment and Urbanization 20 (2): 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247808096126.

- Rootes, C. 2002. “Green Parties: From Protest to Power.” Harvard International Review 23 (4): 78–82.

- Röth, L., and H. Schwander. 2020. “Greens in Government: The Distributive Policies of a Culturally Progressive Force.” West European Politics 44 (3): 661–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1702792.

- Rüdig, W. 2002. “Between Ecotopia Disillusionment: Green Parties in European Government.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 44 (3): 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139150209605605.

- Shaw, K. 2012. “The Rise of the Resilient Local Authority?” Local Government Studies 38 (3): 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2011.642869.

- Spoon, J. 2009. “Holding Their Own: Explaining the Persistence of Green Parties in France and the UK.” Party Politics 15 (5): 615–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809336397.

- Wilson, D., and C. Game. 2002. Local Government in the United Kingdom. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Youm, J., and R. Feiock. 2019. “Interlocal collaboration and local climate protection.” Local Government Studies 45 (6): 777–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1615464.