ABSTRACT

Efforts to enhance urban mobility sustainability face opposition, necessitating citizen acceptance and participation. This study explores the determinants of willingness to engage in digital co-creation for urban mobility planning. The research, conducted in Darmstadt, Germany, examines socio-economic factors, perceptions, and attitudes. Results indicate that financial and time resources have limited influence on participation, emphasising context-specific considerations. Technical proficiency and age impact participation, emphasising the need for user-tailored digital tools. Individual benefits positively motivate participation, while the role of collective benefits is uncertain. Effective communication strategies should stress individual benefits. Surprisingly, perceived efficacy does not positively influence participation. The study enriches the understanding of effective participation strategies in digital co-creation for urban mobility planning, highlighting the multifaceted nature of the process.

Introduction

Efforts to move urban mobility towards sustainability are inherently challenging, and foremost among these challenges is the complex interplay with local attitudes towards urban transport policies and related infrastructure interventions. Despite a prevailing inclination to embrace sustainable mobility, local authorities often face fierce opposition from residents – a phenomenon well captured by the NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) concept, as illustrated by, e.g (Devine-Wright Citation2010). However, for the shift towards a more sustainable mobility paradigm to be effective, it is imperative that citizens accept these initiatives and lead to corresponding behavioural adjustments.

Previous research has shown that involving citizen interests in local policy-making can increase acceptance (Fraune and Michele Citation2019; Geißel Citation2008). This effect is achieved through participation involving citizens in the decision-making process at an early stage and interactively, allowing them to ‘co-create’ the outcome rather than just being informed or consulted on a project. One of the fundamental problems of such early-stage participation in local infrastructure projects is the so-called participation paradox: Given that many citizens may not perceive an immediate and direct impact on their lives, their current inclination to engage in the process remains relatively low, even though they have the opportunity to engage and their potential influence on the final outcome is much more significant in the early stages of the process (Baiocchi Citation2017; Hirschner Citation2017).

Against this background, we want to investigate the determinants that promote or inhibit the willingness to participate in deliberative participation formats in the context of digital and interactive participation tools and ask: What leads to a higher willingness to participate in digital co-creation participation formats?

To answer this question, we first discuss the concepts of digital co-creation participation used in this paper, as our theory and data refer to a special form of deliberative participation. By drawing on data from our survey conducted in the German city of Darmstadt, we analyse the respondents’ socio-economic status, their perceptions and attitudes towards participation and the mobility transformation to explore determinants of the willingness to participate in the digital participation scenario. First, we look at a number of theoretical mechanisms that have been identified in previous research. Then, we deploy a multivariate linear regression model as well as a path analysis model to test our hypotheses. Finally, we discuss our findings and their implications for further developing (digital) participation formats.

Digital participation as co-creation

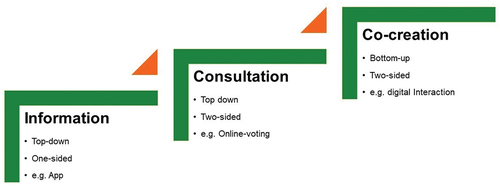

In recent years, there has been a steady growth in the literature on participation at the local level. Within this burgeoning literature, a prominent focus has been on distinguishing between different forms of participation and their respective contributions to enhancing the legitimacy of governance (Fraune and Knodt Citation2017; Nabatchi Citation2010; Quick and Bryson Citation2022). Based on Arnstein’s detailed ‘Ladder of Participation’ (1969), participation processes can be bundled and conceptualised as a three-stage model (): (1) information, (2) consultation, and (3) co-creation (Lortz et al. Citation2022; Lortz, Kachel, and Knodt Citation2021). In the first stage, information is disseminated to citizens in a one-way fashion. In subsequent consultation processes, citizens are actively involved in providing information on specific policy issues, often through means such as surveys or online voting.

Conversely, the co-creation stage involves citizens from the outset, enabling them to organically contribute their perspectives, share knowledge, and engage in mutual learning. In line with the deliberative literature, it is only at the co-creation level that a positive impact on uptake can be seen (Langer et al. Citation2018; Zoellner, Schweizer-Ries, and Wemheuer Citation2008). However, the high level of sophistication of deliberative participation with citizens as ‘co-creators’ remains rare, especially in complex infrastructure projects. This scarcity extends to research on local-level willingness to participate in such formats. Literature has predominantly treated co-creation as a normatively desired objective, while the specific nature and underlying motivations behind this particular form of participation have received comparatively limited attention.

Nevertheless, a considerable amount of studies deal with the question of why people do (not) participate in other formats, for example, voting, social movements, or energy initiatives (Bomberg and McEwen Citation2012; Toft, Schuitema, and Thøgersen Citation2014; Kalkbrenner and Roosen Citation2016; Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018). Some studies point out that the early participation process tends to suffer from a lower willingness to participate (Baiocchi Citation2017; Hirschner Citation2017). We also know from local formats for information and consultation formats that local administrations constantly complain about low participation rates (Fraune et al. Citation2019). In co-creation processes, the willingness to participate is even more crucial as a high level of participation is one of the factors leading to later acceptance of the outcome. This is why we focus on the willingness to participate, especially in co-creation processes, bearing in mind that the effort to identify a mutually agreeable solution is resource-intensive and time-consuming, particularly in the presence of conflicting interests, potentially diminishing the advantages of co-creation.

A more recent strand of research also focuses on new digital tools developed to make co-creation more feasible. One type of tool that has received much attention works with (three-dimensional) visualisations on an interactive display surface. In a deliberative planning process, they are designed to help clarify the tasks or even enable citizens to simulate new solutions (Casper Citation2019; Dettweiler and Linke Citation2019; Spatz, Dettweiler and Linke Citation2019). Additionally, web versions of these tools make co-creation more accessible for people who wish to participate from home via their own devices – albeit this could impose barriers for less technically adept population groups, such as older adults (ficher et al. Citation2020). In the literature, however, their use is usually described only descriptively. Empirical evidence on the relationship between digital formats and the willingness to participate is uncommon and is often limited to internet platforms, such as social media channels (de Marco, Robles, and Antino Citation2014; Lilleker and Koc-Michalska Citation2017). Furthermore, these studies look at digital tools in the form of apps or online surveys that merely provide information or consult people about a specific issue but do not facilitate co-creation (e.g., Matthews et al. Citation2022). Therefore, the question of the influence of the use of digital tools in participation on citizens’ willingness closes another research gap.

The success of any new approach to participation depends on the extent to which individuals are willing to engage with it. As shown, the existing literature on local policy planning has overlooked this crucial aspect. Therefore, this paper addresses this omission by investigating the potential factors influencing people’s willingness to participate in digital co-creation formats.

Willingness to participate in digital co-creation formats

To understand why citizens participate in digital and co-creation participation formats, we will first start from the literature on the cause of political participation from a more general perspective. At this, we draw on the well-established civic voluntarism model (CVM) by Brady, Verba, and Schlozmann (Citation1995). The CVM examines political participation through a rational choice framework, aligning with the theory of rational voter behaviour by Downs (Citation1957). It suggests that individuals make decisions regarding civic engagement based on a cost-benefit analysis, influenced by factors such as their perceived impact on public policy, the costs of participation, and the potential benefits or incentives. In this way, the CVM builds upon Downs’ framework to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how citizens’ rational choices influence their involvement in civic and political activities. The CVM identifies individual and cognitive resources as the main determinants of political participation.

Second, we take psychological or motivational factors into account to explain what motivates people to become politically active (Cohen, Vigoda, and Samorly Citation2001; Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018). In doing so, we especially draw on the research conducted by Cohen, Vigoda, and Samorly (Citation2001). They expanded the original CVM by examining the mediating role of psychological factors. Also, we discuss findings from the social movement literature that offers explanations for people’s motivation to protest or engage in a movement for a collective cause, as we consider co-creation (i.e., joint interactive planning of e-charging stations) as a form of collective action (Haslam Citation2012; Klandermans Citation1984, Citation1997; Stürmer and Lang Citation2007; Stürmer and Simon Citation2004). Furthermore, we consult empirical studies about participation in local communities, as they also represent participation as collective action (Bomberg and McEwen Citation2012; Broman; Toft, Schuitema, and Thøgersen Citation2014; Kalkbrenner and Roosen Citation2016; Fischer, Gutsche, and Wetzel Citation2020). Accordingly, we will subsequently formulate hypotheses on how resources and motivational factors can explain the willingness to participate.

Resources for participation

According to the CVM by Verba et al. (Citation1995), citizens’ participation is primarily a function of the resources they have at their disposal: money, time, and civic skills. Regarding money, the authors argue that individuals possessing greater wealth exhibit distinct interests when it comes to exerting influence over specific public policies (Brady, Verba, and Schlozmann Citation1995; Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 52). The effect of income on political activity has been widely demonstrated, especially in studies on voter turnout (Smets and van Ham Citation2013). Related to our use case, it seems evident that wealthier individuals are more likely to purchase an e-car and thus have an interest in where and how e-charging stations are situated. This assumption can be supported by the argument that the privileged (mostly white, wealthy, etc.) are also more self-confident due to their higher status and, therefore, can promote their arguments well in deliberative processes (Landwehr and Faas Citation2016, 6; Sanders Citation1997). Consequently, we hypothesise the following:

H1:

The higher the income, the higher the willingness to participate.

The issue of time availability, which is closely linked to income, is also frequently raised in the CVM. If no time is available, people cannot pursue political activities (Brady, Verba, and Schlozmann Citation1995; Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 53). Participating in a collaborative planning process takes significantly more time than voting. While income may indicate how much free time is available for political activity, it is not a sufficient condition. Conversely, the occupational status might be more meaningful when assessing someone’s free time. A full-time employee has arguably less time than pensioners for being politically active. For example, full-time employees usually have less time than pensioners. Another crucial consideration pertains to the presence of children, particularly when they are very young, as they demand a significant amount of time. In cases where a parent chooses to stay at home or work part-time, the extent of time required is not solely determined by their occupational status. We, therefore, assume that:

H2:

The more time someone has, the higher their willingness to participate.

The third type of resource is what Schlozman, Brady, and Verba (Citation2018, 54) call civic skills. In general, this refers to cognitive abilities enabling individuals to engage with political issues and processes and to form one’s preferences. More precisely, these skills strengthen not only the abilities but also the need for participation. We rename civic skills to cognitive skills as we expand the concept to include skills that are relevant to digital formats.

Cognitive skills can be mapped through educational attainment. With regard to education, empirical studies have convincingly shown that a higher level of education increases political participation (Brady, Verba, and Schlozmann Citation1995; Kam and Palmer Citation2008; Mayer Citation2011; Persson Citation2015; Steinbrecher, Huber, and Rattinger Citation2007, 287). However, education as a proxy variable for cognitive ability remains contentious, as the overall increase in educational attainment across society, for example, is not associated with higher participation (Burden Citation2009; Condon Citation2015; Persson Citation2015). In addition, education may correlate with income, as a higher degree of (formal) education can grant more access to higher-paying jobs. Nevertheless, we conclude:

H3:

The higher someone’s education, the higher their willingness to participate.

In our case, the ability to use digital tools is also relevant when assessing cognitive skills. For this, a certain affinity for technology is important, which facilitates or enables the use of the digital participation tool. Not only a general affinity for technology is crucial, but also experience with similar technological applications (Choi, Glassman, and Cristol Citation2017; de Marco, Robles, and Antino Citation2014). We, therefore, argue that, in addition to general education, technology affinity is also part of the cognitive skills:

H4:

The higher the affinity for technology, the greater their willingness to participate.

The formation of cognitive skills is also shaped by everyday working life and involvement in organisations; additional skills are developed that enable or increase interest in political participation (Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 55f.). Crucially, political engagement teaches skills that are relevant to political participation.

H5:

Those who are involved in other political institutions or associations tend to have a higher willingness to participate.

We further assume that cumulative political experience increases with age. This goes hand in hand with greater civic skills (Quintelier Citation2015; Verba and Nie Citation1972, 138). After a certain age, the willingness may decrease again due to illness or increasing immobility, which is why the relationship can also be described as curvilinear. Regarding the digital participation format, we must also consider that older people may have a lower affinity for technology, so older people may be less willing to participate. Thus, we assume that age is mediated by political engagement and affinity for technology:

H6:

The older someone is, the higher their political engagement, which increases their willingness to participate.

H7:

The older someone is, the lower their technical abilities, which reduces their willingness to participate.

Motivational factors

Resources are a necessary but not a sufficient condition for being politically active. So, what motivates people to use their resources for political participation? In the CVM, the authors assume that while resources are crucial, people also need to be psychologically engaged, i.e., ‘[…] to be aware of, know something about, and care about politics and public issues; and to believe that they can, in fact, have a voice’ (Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 58). Adding to Schlozman, Brady, and Verba (Citation2018), the problem of causal direction emerges, as psychological engagement with politics can lead to both active participation and non-participation. Consequently, we will not simply include psychological factors as additional independent variables directly affecting willingness. Rather, following Cohen, Vigoda, and Samorly (Citation2001), we see psychological factors in a mediating role.

In CVM, the authors interpret political interest, efficacy beliefs, information, and party identification as decisive factors for psychological engagement. These factors can only be transferred to our context to a limited extent. In our scenario, we are not concerned with participation in politics in general but rather with participation in a specific project, which corresponds to at least a moderate form of collective action. At this point, we refer to concepts which have been discussed in research on social movement mobilisation and which independently lead to participation motivation (Olson Citation1977; Stürmer and Simon Citation2004; Haslam Citation2012, 207 ff.; Kalkbrenner and Roosen Citation2016).

One approach is based on the logic of the rational choice theory, drawing on Downs theory (Citation1957), in which motivation results from a calculation of costs and benefits. This means that citizens must believe that they will achieve a collective or individual benefit through participation (Stürmer and Simon Citation2004; van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2013).

In our scenario, citizens may interpret the expansion of charging stations as a means to increase a collective good they endorse, such as climate protection. The individual benefit, meanwhile, results from personal interests. It is especially high if people are affected by the project, i.e., benefit from charging stations in their neighbourhood because they own an e-car or want to purchase one in the near future. As discussed in the previous section, the cognitive resources of education and money do influence the willingness to participate and come into question as a cause – but they do so by indirectly shaping interests in the policy. Therefore, we test the following hypotheses:

H8a:

The more someone supports the mobility transformation, the higher their willingness to participate.

H8b:

The more someone supports the expansion of charging stations, the higher their willingness to participate.

H9:

Someone who is affected by a project’s goal (i.e., owns or wants to purchase an e-car) tends to have a higher willingness to participate than someone who is not affected.

H10:

Individual and collective interests mediate the influence of education and money on willingness to participate.

The literature that follows the logic of rational choice also highlights the factor of efficacy beliefs, which is assumed to influence motivation to participate (Bandura Citation1997; van Zomeren, Saguy, and Schellhaas Citation2013). Several empirical studies suggest that citizens need to perceive that they can achieve their own or collective interests through their participation (Bomberg and McEwen Citation2012; Cohen, Vigoda, and Samorly Citation2001; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2013). A distinction can be made between internal and external efficacy. Internal efficacy encompasses the self-esteem to influence the political system, i.e., the expected influence through political participation. In contrast, external efficacy means the perceived responsiveness of the system, i.e., satisfaction with participation opportunities (McPherson, Welch, and Clark Citation1977; Niemi, Craig, and Mattei Citation1991; Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 59). Perceived efficacy (internal and external) is one of the explanations of why money has an impact on willingness to participate. Education and engagement as cognitive skills also shape efficacy beliefs because they impart information and knowledge about government, institutions, and societal relationships. Thus, we assume:

H11:

The higher someone perceives their potential influence through participation, the higher their willingness to participate.

H12:

The more satisfied someone is with existing participation formats, the higher their willingness to participate.

H13:

The influence of money and cognitive skills are mediated by efficacy beliefs.

However, the cost-benefit approach alone cannot explain participation. Its individualistic perspective on costs and benefits disregards any group memberships or other inter-group dynamics that potentially influence someone’s decision-making (Stürmer and Simon Citation2004, 65).

In that perspective, identification processes play a role, which can occur independently of resources or calculated utility (Haslam Citation2012; Stürmer and Simon Citation2004; van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2013). The CVM points to the influence of party identification, which is independent of direction and is similarly distributed across all educational attainment levels (Schlozman, Brady, and Verba Citation2018, 60–61). Related to collective action, identification refers to the sense of belonging to a social group. Empirical studies have shown, for example, that identification with the local community and a ‘sense of community’ is crucial when citizens volunteer for local projects (Kalkbrenner and Roosen Citation2016; Stürmer and Kampmeier Citation2003). The sense of community can strengthen solidarity and take hold even when individuals do not benefit from participation (Toft, Schuitema, and Thøgersen Citation2014). Urban mobility planning is usually about projects within a specific neighbourhood, and so is the planning of charging stations. For this reason, we refer to the identification with one’s own neighbourhood and conceptualise community identity similar to Kalkbrenner and Roosen (Citation2016) with (1) the felt strength of connection to the community, (2) the number of friends living in the community, and (3) if the respondent only lives in the district because they did not find an apartment elsewhere and assume:

H14:

The higher someone’s community identity, the higher their willingness to participate.

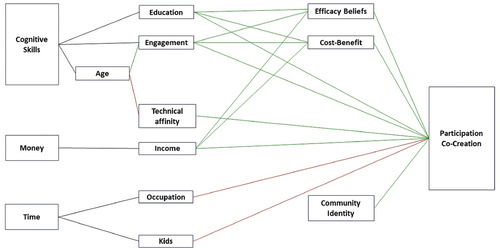

In , we summarised our hypotheses in a path model that shows our presumed causal relationships (direct and indirect) between the individual variables (red = negative relation and green = positive relation). The operationalisation of the mapped concepts is presented in the next section.

Methods

We employ a quantitative estimation strategy to test our hypotheses using data from a representative survey we conducted in three city districts of Darmstadt, Germany, in 2021.Footnote1 For these three districts, Lincolnsiedlung (District 440), Mollerstadt (District 120), and Heimstättensiedlung (District 520), we requested a disproportionate register-based sample from the municipal registration office. The registration office was asked to identify 1,700 addresses per district based on the following parameters: residents aged 18 and older, name, and address. The registration office deployed interval sampling as the sampling method.Footnote2 The total sample size for the survey was 5,004 people (total population = 14,689) living in the three districts. The invitation to participate was sent by letter with online access to the survey. With a response rate of 9.6%, the survey sample consisted of 481 respondents. Of these 481 responses, 12 responses were excluded due to invalidity.Footnote3

To test our hypothesis, we first developed an ordered logistic regression model estimating the direct effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable, i.e., people’s willingness to participate in digital urban mobility planning.Footnote4 Second, we tested the assumed mediation effects via path analysis, which is a type of structural equation modelling (SEM).Footnote5 The concrete model specifications, along with the results, are displayed in .

Conceptualisation and operationalisation

Within the PaEGIE project, two practice-oriented scenarios concerning urban mobility planning were developed to pilot a digital participation tool developed by Fraunhofer IGD.Footnote6 Both were initially programmed as a web application for a multi-touch table (MTT) or one’s own PC from home and are to be made usable later for smartphones. Our dependent variable refers to the respondents’ willingness to participate in scenario 1, which deals with the local planning of e-charging stations in a digital 3D city model. Citizens can make their own suggestions within the application about where the charging points should be placed, test them graphically and share them with other users. The suggestions can then be discussed among citizens, with the city or other relevant stakeholders and experts (e.g., local energy suppliers), and commented on concerning technical and legal feasibility. This interactive exchange makes it possible to co-create the planning of charging stations. shows a screenshot of this tool.

Figure 3. Case scenario I – Planning of electric charging stations. Source: Fraunhofer-institut für Graphische Datenverarbeitung.

The survey asked whether the respondents would participate in this co-creation scenario. The responses were captured by a four-level Likert scale: ‘No, in no case’; ‘Likely not’; ‘Likely yes’; ‘Yes, absolutely’; ‘I don’t know’. A detailed overview of the items we used for the operationalisation of the independent variables can be found in in the appendix.

For higher reliability of the items, two pre-tests were conducted before the survey. Similar to the Cognitive-Think-Aloud method, the questionnaire was tested in several rounds by students and staff with the request to note down all thoughts and conspicuities during the completion. Language revisions were made to questions that were not understood correctly or could lead to misunderstanding. In a second pre-test, the survey was administered to a randomly selected subsample (n = 400)of the total sample (n = 5004). Out of the 400 residents, 52 responded. The generated data set could be added to the final data set, as the second pre-test did not warrant any changes to the survey.

Results and discussion

Ordered logistic regression model

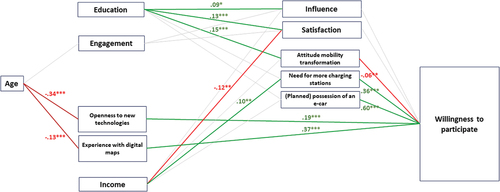

For the first part of our analysis, we built a model that measures our predicted direct effects. As the dependent variable is an ordinal variable with only four levels, we deploy an ordered logistic regression model. The other independent variables that are also based on Likert-scale survey items have more levels and are treated as continuous variables. Given the selection of survey items in the course of the operationalisation and since we only included complete cases,Footnote7 the final research sample consists of 304 cases. In the following, we first discuss the direct effects related to the resources for participation (H1 to H5). We then turn to the results regarding the direct effects of the hypothesised motivational factors (H8 to H9, H11 to H12, H14). displays the results as log odds. The raw regression estimates can be found in in the appendix.Footnote8

Figure 4. Ordered logistic regression results. For better interpretability, coefficients were converted to log odds along with their confidence intervals. The (flipped) y-axis was transformed into logged values (log base 10) to enhance readability. The stars represent the significance levels (*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01).

Financial and time resources measured by income level and mode of employment do not have any significant effect on people’s willingness to participate in scenario 1, contradicting our expectations of H1 and H2. In addition, opposing our expectations of H2, having children even has a strong positive effect. This could mean that having children is not a time factor, as we anticipated (H2), but that it appeals to other mechanisms such as community identity. Parents could be more likely to be invested in their district as they are less likely to move away or as they are more likely to be connected to other residents, e.g., through school.

The level of education has a statistically significant, albeit relatively small and negative effect, which contradicts H3. The path analysis model (see below) suggests that this is due to the mediating effects assumed in H10 and H13. The statistically significant and positive effect of technology openness and experience with digital maps is consistent with our predictions of the fourth hypothesis. This underlines the importance of using digital tools that are accessible to as many people as possible. For instance, a systematic lack of technical skills among certain population groups might hinder them from participating in digital participation formats. As expected, previous political engagement has a positive effect on the willingness to participate. However, it is just barely not statistically significant. Therefore, we cannot confirm H5. One reason for this could be that the survey respondents exaggerated their political engagement due to the perceived social desirability of being politically active. The model also estimates the direct effect of age; it does not find any statistically significant effects which could indicate existing mediating effects with other variables, as hypotheses 6 and 7 suggest. The path model analysis provides further insight into this matter. The motivational factors identified above include hypotheses on cost-benefit calculations (H8 & H9), efficacy beliefs (H11 to H12) as well as community identity (H14). The effects of cost-benefit calculations are mixed: Although both the attitude towards mobility transformation and (planned) possession of an electric car are statistically significant, they point at different directions. The former appears to have a slightly negative relationship with willingness to participate, which contradicts H8a. The latter seems to have a strong positive effect on the dependent variable – the strongest effect in the model. This confirms our expectations (H9). Interestingly, support for the expansion of charging stations has a statistically significant positive effect, thus confirming H8b. In light of the negative effect of attitude towards the mobility transformation, this suggests, as we presumed, that the specific issue of the charging station planning fails to establish a link to the more general collective good of the mobility transformation. The model does not indicate that efficacy beliefs seem to play a role in people’s willingness to participate in our use case. Both the potential influence people perceive to have in the mobility transformation and their satisfaction with existing participation opportunities do not have a significant effect (rejecting H11 and H12). This could be due to face validity issues: The survey respondents may not mentally associate scenario 1 with the (non-co-creation) forms of citizen participation prevalent in the city of Darmstadt, and citizens may have a different expectation of the efficacy of the scenario presented. Thus, the operationalisation we use for efficacy beliefs cannot be conceptually applied to co-creation participation formats.

Lastly, neither of the variables representing an individual’s degree of integration in his or her district has a statistically significant effect.Footnote9 Contrary to H14, the standard error of the variable ‘integration in district I’ even suggests a negative influence on someone’s willingness to participate. This puzzling effect needs further exploration.

Path analysis model

To test the mediation effects identified in our hypotheses 6, 7, 10, and 13, we conducted a path analysis, with the dependent variable specified as an ordered variable and the independent variables defined as continuous or binary variables. summarises the results. [ near here, if possible on a whole page] Regarding age, the results are mixed: The previous political engagement does not seem to have a mediating effect between age and the willingness to participate, contradicting H6. Being previously politically engaged appears to have a positive effect on the willingness to participate. However, there is no statistically significant link between age and previous engagement. Contrarily, there is evidence supporting hypothesis 7: Higher age is associated with less openness to technology and less experience with digital maps, which in turn has a positive effect on willingness to participate. These indirect effects are statistically significant. At the same time, there is no statistically significant direct effect of age.Footnote10 These results underline the importance of designing inclusive digital tools that do not unintentionally discriminate against certain population groups, such as older adults. The model indicates that individual and collective interests at least partly mediate the effect of education and money on the willingness to participate (H10). A person’s level of education appears to have a statistically significant positive effect on their attitude towards the mobility transformation, whereas a more positive attitude seemingly reduces their willingness to participate. This could explain the negative direct effect of education measured by the multivariate linear regression model above. Furthermore, there is a statistically significant mediating effect between education/income, the planned (possession) of an e-car, and the dependent variable: Not surprisingly, a higher level of income increases the individual interest in charging stations because high earners are more likely to (be able to) purchase or possess an e-car. These indirect effects could also explain why earlier income did not have positive significant direct effects.

Figure 5. Results of the path analysis model (mediation only). Partial results of the path analysis model. The figure depicts only the estimated mediation effects. Green lines indicate an estimated positive and statistically significant relationship; red lines indicate an estimated negative and statistically significant relationship. A grey line indicates that the estimation did not find a statistically significant relationship. The numbers represent the regression coefficients, the stars represent the significance levels (*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01).

Regarding efficacy beliefs, there are apparently no statistically significant mediating effects on income and civic skills, hence rejecting H13. While a higher level of education has a statistically significant and positive association with the efficacy variables, there is no such link between efficacy beliefs and willingness to participate. Similarly, income appears to decrease efficacy beliefs (the effect on perceived influence just fails to be statistically significant), while there is no such effect between efficacy beliefs and the dependent variable. Here, the previously discussed face validity problems could play a role again.

We assessed the model’s fit through the model’s chi-squared, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, and Comparative Fit Index. All measures indicate a suboptimal goodness of fit. This is not surprising, given the amount of statistically insignificant relationships within the model – highlighting that traditional explanations for participation are not necessarily applicable to digital co-creation formats.

Conclusion

In our quest to understand the determinants of willingness to engage in digital co-creation participation formats in the realm of urban mobility planning, we have explored several key factors. While our study did not reveal direct evidence suggesting that financial and time resources influence an individual’s inclination to participate in a co-creation format for planning e-charging stations within their city district, our findings align with the broader Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM) literature. This body of work, encompassing studies such as Barkan (Citation2004), Nygård and Jakobsson (Citation2013), Kim and Khang (Citation2014), and Oni et al. (Citation2017), has consistently shown that the impact of financial and time factors varies depending on the type of participation under consideration. Unless respondents perceive a particular political activity as highly demanding in terms of time or money, these factors are unlikely to significantly influence their decision to participate. Therefore, it can be inferred that our survey participants may not have had a clear grasp of the time commitment and financial costs associated with the given participation format. Utilising a mobile app or web application as a digital tool in the scenario demands fewer resources compared to physical participation, potentially explaining the absence of significant effects in our models. This nuanced understanding contributes to the existing literature by shedding light on the context-dependent nature of resource considerations in participation dynamics.

Our findings underscore the importance of considering individuals’ varying levels of technical proficiency when incorporating digital tools into participation processes, which is still under-evaluated in the existing literature. The use of complex digital tools may deter participation among those with limited technical skills. Age, as revealed by our path analysis model, aligns with this observation. Digital tools can act as both barriers and facilitators, depending on the demographics of the user. It would be beneficial for future research to delve deeper into potential synergies between digital tools and resource availability. For instance, investigating whether digital tools can enhance participation willingness by minimising resource demands.

Regarding the psychological aspects of participation, our findings support the notion that individual benefits positively influence the willingness to participate. People are more inclined to engage in a policy initiative when they can directly benefit from it. However, the concept of collective benefit posed challenges when applied to an urban mobility planning project. The model, serving as a somewhat broad proxy for collective benefit, surprisingly revealed a slightly negative impact of attitudes towards the mobility transformation on the willingness to participate, contrary to our expectations. On the other hand, we observed a positive effect concerning the perceived need for additional charging stations.

Nevertheless, it remains somewhat ambiguous whether collective or individual cost-benefit considerations played a more significant role in this regard. Hence, it can be inferred that effective communication strategies for mobilising participation should focus on articulating the individual benefits. Future studies may explore experimental approaches to investigate communication strategies that enhance willingness to participate.

Our model yielded unexpected results when it comes to the very unspecific proxy for collective benefit. The model calculated, against our expectations, a slightly negative effect of attitude towards the mobility transformation on the willingness to participate. The perceived need for more charging stations, on the other hand, had a positive effect. In contrast, a positive influence was observed in the case of the perceived need for additional charging stations. Yet, the distinction between collective and individual cost-benefit calculations remains somewhat elusive. Therefore, it becomes evident that effective mobilisation efforts for participation formats should adopt a communication strategy tailored to individual benefits. Future research endeavours could explore experimental methodologies to investigate specific communication strategies that stimulate a greater willingness to participate.

An intriguing observation in our study is that perceived efficacy does not exhibit a positive influence on the willingness to participate, contrary to the consistent findings in research on traditional participation and collective action (e.g., energy communities or social movements), where efficacy is identified as a significant factor (McDonnell Citation2020). This deviation could be attributed to the specific context of our participation scenario, though the underlying mechanisms remain somewhat obscure. It is also possible that within our efficacy measures, particularly when people were asked about their satisfaction with their prior participation experiences, they may not have connected this participation with the scenario presented later in the questionnaire. Future research may consider adopting more generalised efficacy measures (e.g., Niemi, Craig, and Mattei Citation1991)to gain further insights. In conclusion, our study highlights that reaching the co-creation stage is only one part of the equation in the design of local-level participation processes. Mobilising individuals and expanding the target group are equally critical facets to consider, enriching the existing literature by emphasising the multifaceted nature of effective participation strategies.

In conclusion, our study underscores the adaptability of numerous well-established concepts from the broader participation literature to the unique context of digital co-creation within urban mobility planning. However, our findings also reveal that some of these concepts may not be directly transferrable, with efficacy beliefs being a particularly unexpected case. This could potentially be attributed to issues related to operationalisation. A limitation of this analysis lies in the challenge of effectively capturing certain nuanced concepts through questionnaire-based surveys. While our research offers valuable insights, it also highlights the need for more in-depth exploration and measurement of these concepts, enriching the discussion on the application of participation theories to emerging forms of digital co-creation in the realm of urban mobility planning.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and analysis were carried out within the interdisciplinary project “Participative Energy Transformation: Innovative Digital Tools for the Social Dimension of the Energy Transition” (PaEGIE) (11/2020-4/2023) conducted by Prof. Dr. Michèle Knodt (Institute for Political Science) and Prof. Dr.-Ing. Hans-Joachim Linke (Institute of Geodesy) and the Fraunhofer Institute for Computer Graphics Research IGD, Dr. Eva Klien. For details see: www.paegie.de. This work was presented in a first version at the ECPR Conference 2022 in Innsbruck, Austria. We thank our panel for their valuable input, which we have considered in this revision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. With 160,000 inhabitants, Darmstadt is a city located in the southern Rhine-Main metropolitan area and has ideal conditions for the overall experimental project goals. Darmstadt was named a model project for the ‘digital city’ of the future. The city also focuses its policies relevant to the project’s fields of interest: Energy transition, mobility, digitisation, and citizen participation. The city is also experimenting with the newly founded platform ‘da-bei.darmstadt.de’ to increase citizen participation. In the three distinct city districts characterised by varying demographics and infrastructure, the survey gathered information on individuals’ preferences and perceptions concerning participation in both general terms and specific to digital participation scenarios. For further details about the survey see also: Lortz, Kachel, and Knodt (Citation2021).

2. The interval sampling involved a fixed interval and a random starting number. In order to determine this fixed interval, we calculated the total number of potential recipients in each district. This number was then divided by the requested data quantity (1700). The result was rounded to the nearest whole number, which became the fixed interval. The starting number, on the other hand, was determined by halving the interval.

3. Eight respondents did not specify which district they live in, four others stated that they do not live in any of the districts.

4. For this, we used the ‘polr’ function of the R package MASS.

5. For this, we employ the lavaan R Package (Rosseel Citation2012).

6. For an impression of the tool, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3BahhXvlg4&t=2s

7. That is, not all respondents answered all survey questions used for the modelling. The regression model, however, only includes cases with complete data. Accordingly, those cases with incomplete data are omitted in the analysis.

8. We calculated the Brant Test to test the parallel regression assumption, a prerequisite for building an ordered logistic regression model (Brant Citation1990). The parallel regression assumption holds.

9. We did not form a scale, because our three items fail to be sufficiently internally consistent (Cronbach’s = 0.6).

10. When excluding technology openness and experience with digital maps from the model, the direct effect of age and willingness to participate becomes statistically significant and negative.

References

- Baiocchi, G. 2017. Popular Democracy: The Paradox of Participation. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Barkan, S. E. 2004. “Explaining Public Support for the Environmental Movement: A Civic Voluntarism Model.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (4): 913–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00251.x.

- Bomberg, E., and N. McEwen. 2012. “Mobilizing Community Energy.” Energy Policy 51:435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.08.045.

- Brady, H. E., S. Verba, and K. L. Schlozmann. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” The American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082425.

- Brant, R. 1990. “Assessing Proportionality in the Proportional Odds Model for Ordinal Logistic Regression.” Biometrics 46 (4): 1171. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532457.

- Burden, B. C. 2009. “The Dynamic Effects of Education on Voter Turnout.” Electoral Studies 28 (4): 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2009.05.027.

- Casper, E. A. 2019. “Die Karten Auf Den Tisch Legen: Einflüsse Des Digitalen Partizipationssystems (DIPAS) Auf Das Planungsverständnis Von Bürgerinnen Und Bürgern – Ein Praxistest in Hamburg.” Accessed March 7, 2022. https://dipas.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Casper_Masterarbeit_Die%20Karten%20auf%20den%20Tisch%20legen.pdf.

- Choi, M., M. Glassman, and D. Cristol. 2017. “What It Means to Be a Citizen in the Internet Age: Development of a Reliable and Valid Digital Citizenship Scale.” Computers & Education 107 (2): 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.002.

- Cohen, A., E. Vigoda, and A. Samorly. 2001. “Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Personal-Psychological Variables on the Relationship Between Socioeconomic Status and Political Participation: A Structural Equations Framework.” Political Psychology 22 (4): 727–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00260.

- Condon, M. 2015. “Voice Lessons: Rethinking the Relationship Between Education and Political Participation.” Political Behavior 37 (4): 819–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9301-0.

- de Marco, S., J. M. Robles, and M. Antino. 2014. “Digital Skills as a Conditioning Factor for Digital Political Participation.” Communications 39 (1): 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2014-0004.

- Dettweiler, M., and H.-J. Linke. 2019. “Forschung Bringt Neuen Schwung in Stadtentwicklungsprozesse.” RaumPlanung 200 (1–2019): 56–60.

- Devine-Wright, P., ed. 2010. Renewable Energy and the Public: From NIMBY to Participation. London: Earthscan.

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Fischer, D., F. Brändle, A. Mertes, L. E. Pleger, A. Rhyner, and B. Wulf. 2020. “Partizipation im digitalen Staat: Möglichkeiten und Bedeutung digitaler und analoger Partizipationsinstrumente im Vergleich.” Swiss Yearbook of Administrative Sciences 11 (1): 129–144. https://doi.org/10.5334/ssas.141.

- Fischer, B., G. Gutsche, and H. Wetzel. 2020. “Who Wants to Get Involved? Determinants of Citizens’ Willingness to Participate in German Renewable Energy Cooperatives.” MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics 27-2020.

- Fraune, C., and M. Knodt. 2017. “Challenges of Citizen Participation in Infrastructure Policy-Making in Multi-Level Systems-The Case of Onshore Wind Energy Expansion in Germany.” European Policy Analysis 3 (2): 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1022.

- Fraune, C., M. Knodt, S. Gölz, and K. Langer, eds. 2019. Akzeptanz Und Politische Partizipation in Der Energietransformation: Gesellschaftliche Herausforderungen Jenseits Von Technik Und Ressourcenausstattung. Energietransformation. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Fraune, C., and K. Michele. 2019. “Politische Partizipation in Der Mehrebenengovernance Der Energiewende Als Institutionelles Beteiligungsparadox.” In Akzeptanz Und Politische Partizipation in Der Energietransformation: Gesellschaftliche Herausforderungen Jenseits Von Technik Und Ressourcenausstattung, edited by C. Fraune, M. Knodt, S. Gölz, and K. Langer, Energietransformation 159–182. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Geißel, B. 2008. “Wozu Demokratisierung der Demokratie? – Kriterien zur Bewertung partizipativer Arrangements.” In Erfolgsbedingungen lokaler Bürgerbeteiligung, edited by A. Vetter, 29–49. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Haslam, S. A. 2012. Psychology in Organizations: The Social Identity Approach. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hirschner, R. 2017. “Beteiligungsparadoxon in Planungs- Und Entscheidungsverfahren.” Forum Wohnen und Stadtentwicklung 6:323–326. https://www.vhw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/08_publikationen/verbandszeitschrift/FWS/2017/6_2017/FWS_6_17_Beteiligungsparadoxon_in_Planungs_und_Entscheidungsverfahren_R._Hirschner.pdf.

- Kalkbrenner, B. J., and J. Roosen. 2016. “Citizens’ Willingness to Participate in Local Renewable Energy Projects: The Role of Community and Trust in Germany.” Energy Research & Social Science 13:60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.006.

- Kam, C. D., and C. L. Palmer. 2008. “Reconsidering the Effects of Education on Political Participation.” The Journal of Politics 70 (3): 612–631. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080651.

- Kim, Y., and H. Khang. 2014. “Revisiting Civic Voluntarism Predictors of College Students’ Political Participation in the Context of Social Media.” Computers in Human Behavior 36 (6092): 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.044.

- Klandermans, B. 1984. “Mobilization and Participation: Social-Psychological Expansisons of Resource Mobilization Theory.” American Sociological Review 49 (5): 583–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095417.

- Klandermans, B. 1997. The Social Psychology of Protest. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Landwehr, C., and T. Faas. 2016. “‘Who Wants Democratic Innovations, and Why?’ Gutenberg School of Management and Economics & Research Unit ‘Interdisciplinary Public Policy.’ Discussion Paper Series, (1705): 1–17.

- Langer, K., T. Decker, J. Roosen, and K. Menrad. 2018. “Factors Influencing Citizens’ Acceptance and Non-Acceptance of Wind Energy in Germany.” Journal of Cleaner Production 175:133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.221.

- Lilleker, D. G., and K. Koc-Michalska. 2017. “What Drives Political Participation? Motivations and Mobilization in a Digital Age.” Political Communication 34 (1): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1225235.

- Lortz, M., J. Kachel, and M. Knodt. 2021. PaEGIE Quartiersbefragung: Deskriptiver Datenreport. PaEGIE-Kurzberichte im Rahmen des Projekts “Partizipative Energietransformation: Innovative digitale Tools für die gesellschaftliche Dimension der Energiewende”. Darmstadt: TU Darmstadt und Fraunhofer IGD. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://download.hrz.tu-darmstadt.de/media/FB02/www.politikwissenschaft/Arbeitsbereich_Vergleich_Integration/bericht_paegie_datenreport.pdf.

- Lortz, M., J. Stahl, L. Ritter, I. Iovine, B. Abb, E. Klien, H.-J. Linke, and M. Knodt. 2022. “Digitale Beteiligung in Der Städtischen Mobilitätsplanung.” Flächenmanagement und Bodenordnung 2 (2022): 75–86.

- Matthews, P., A. Parsons, E. Nyanzu, and A. Rae. 2022. “Dog Fouling and Potholes: Understanding the Role of Coproducing ‘Citizen Sensors’ in Local Governance.” Local Government Studies 49 (5): 908–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2116575.

- Mayer, A. K. 2011. “Does Education Increase Political Participation?” The Journal of Politics 73 (3): 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238161100034X.

- McDonnell, J. 2020. “Municipality Size, Political Efficacy and Political Participation: A Systematic Review.” Local Government Studies 46 (3): 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1600510.

- McPherson, J. M., S. Welch, and C. Clark. 1977. “The Stability and Reliability of Political Efficacy: Using Path Analysis to Test Alternative Models.” American Political Science Review 71 (2): 509–521. https://doi.org/10.2307/1978345.

- Nabatchi, T. 2010. “Addressing the Citizenship and Democratic Deficits: The Potential of Deliberative Democracy for Public Administration.” The American Review of Public Administration 40 (4): 376–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074009356467.

- Niemi, R. G., S. C. Craig, and F. Mattei. 1991. “Measuring Internal Political Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study.” The American Political Science Review 85 (4): 1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963953.

- Nygård, M., and G. Jakobsson. 2013. “Political Participation of Older Adults in Scandinavia - The Civic Voluntarism Model Revisited? A Multi-Level Analysis of Three Types of Political Participation.” International Journal of Ageing & Later Life 8 (1): 65–96. https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.12196.

- Olson, M. 1977. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Vol. 124. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Oni, A. A., S. Oni, V. Mbarika, and C. K. Ayo. 2017. “Empirical Study of User Acceptance of Online Political Participation: Integrating Civic Voluntarism Model and Theory of Reasoned Action.” Government Information Quarterly 34 (2): 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.02.003.

- Persson, M. 2015. “Education and Political Participation.” British Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 689–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000409.

- Quick, K. S., and J. M. Bryson. 2022. “Public Participation.” In Handbook on Theories of Governance, edited by C. K. Ansell and J. Torfing, 158–168. Second ed. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Quintelier, E. 2015. “Intergenerational Transmission of Political Participation Intention.” Acta Politics 50 (3): 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.19.

- Rosseel, Y. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Sanders, L. M. 1997. “Against Deliberation.” Political Theory 25 (3): 347–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591797025003002.

- Schlozman, K. L., H. E. Brady, and S. Verba. 2018. Unequal and Unrepresented: Political Inequality and the People’s Voice in the New Gilded Age. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Smets, K., and C. van Ham. 2013. “The Embarrassment of Riches? A Meta-Analysis of Individual-Level Research on Voter Turnout, Electoral Studies.“ http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.006.

- Spatz, L., M. Dettweiler, and H.-J. Linke. 2019. “Neue Blickwinkel – Visualisierung Im Partizipationsprozess.” Kursbuch Bürgerbeteiligung, edited by Jörg Sommer, 313–329. 3nd ed. Berlin: Berlin Institut für Partizipation.

- Steinbrecher, M., S. Huber, and H. Rattinger. 2007. Turnout in Germany: Citizen Participation in State, Federal, and European Elections Since 1979. Studien zur Wahl- Und Einstellungsforschung. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Stürmer, S., and C. Kampmeier. 2003. “Active Citizenship: The Role of Community Identification in Community Volunteerism and Local Participation.” Psychologica Belgica 43 (1–2): 103–122.

- Stürmer, S., and M. Lang. 2007. “Sozialpsychologische Prinzipien Der Mobilisierung Und Partizipation: Potenziale Der Gemeindepsychologie Für Die Raumplanung Im Stadtquartier.” RaumPlanung 130:73–77.

- Stürmer, S., and B. Simon. 2004. “Collective Action: Towards a Dual-Pathway Model.” European Review of Social Psychology 15 (1): 59–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280340000117.

- Toft, M. B., G. Schuitema, and J. Thøgersen. 2014. “The Importance of Framing for Consumer Acceptance of the Smart Grid: A Comparative Study of Denmark, Norway and Switzerland.” Energy Research & Social Science 3:113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.07.010.

- van Stekelenburg, J., and B. Klandermans. 2013. “The Social Psychology of Protest.” Current Sociology 61 (5–6): 886–905. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113479314.

- van Zomeren, M., T. Saguy, and F. M. H. Schellhaas. 2013. “Believing in “Making a Difference” to Collective Efforts: Participative Efficacy Beliefs as a Unique Predictor of Collective Action.” Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 16 (5): 618–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212467476.

- Verba, S., and N. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row.

- Verba, S., K. L. Schlozman, and H. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Zoellner, J., P. Schweizer-Ries, and C. Wemheuer. 2008. “Public Acceptance of Renewable Energies: Results from Case Studies in Germany.” Energy Policy 36 (11): 4136–4141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.06.026.

Appendices

Operationalisation

Table A1. Operationalisation: survey variables assessed in the analysis.

Raw estimates of the ordered logistic regression

Table A2. Ordered logistic regression results.