ABSTRACT

Local governments across the world are adopting new digital technologies to improve their services and to create public value. These new digital technologies challenge traditional forms of leadership. So far, few empirical studies have focused on what digital transformation implies for leadership in the public sector. Based on theories of leadership, digital transformation, and public value, we identify nine dimensions of digital leadership. Based on these dimensions, we examine how city managers across the Netherlands are leading their organizations during the digital transformation. Our findings show that city managers need to develop a value-based vision regarding digital transformation, pay attention to different forms of legitimacy, be consciously aware of the ethical dilemmas and implications of digital technologies, involve politicians more and earlier in technology projects, and stimulate digital competencies of themselves and of public servants. We conclude that ‘digital leadership’ requires both new and existing leadership dimensions.

1. Introduction

Local governments around the world are implementing new digital technologies across different policy domains and functions (Criado and Gil-Garcia Citation2019). These new technologies are changing the landscape of public management and the capacities of local governments to create public value (Bannister and Connolly Citation2014; Criado and Gil-Garcia Citation2019). The growing complexity of the new wave of digital technologies requires new ways of working (Andrews Citation2019; Criado and Gil-Garcia Citation2019; Da Rosa and De Almeida Citation2017; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019; Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020). Previous waves of digitalisation focused on the transition from analog to (parallel) digital services to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of government services. The digital transformation on the other hand, redesigns, and reengineers government services from the ground up to fulfil changing (internal and external) user needs (Mergel et al. Citation2018). For government organisations, digital transformation is as much about the technologies as it is about creating the organisational environment for change to happen (Curtis Citation2019; Gong, Yang, and Shi Citation2020; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). Hence, digital transformation needs to be understood as a comprehensive organisational process. In this transformation process, leadership plays an important role (Frick et al. Citation2021; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019; Schwarzmuller et al. Citation2018).

This study is motivated by two gaps in the literature. First, studies have been conducted on leadership and the digital transformation in the private sector (Frick et al. Citation2021, Citation2021), but there is a lack of empirical studies that focus on what digital transformation requires from leadership in the public sector (Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019; Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020). Without a clear understanding of what digital leadership implies for public managers, local governments might be limited in their ability to advance the digital transformation. Second, the digital transformation is throwing up new challenges for leadership and the creation of public value (Andrews Citation2019; B. D. Mittelstadt et al. Citation2016). For example, it requires leadership that can assess risks of technologies such as bias and privacy, and it requires leadership that takes appropriate action and guarantees fundamental rights (Curtis Citation2019; Sarker, Wu, and Hossin Citation2018; Van der Wal Citation2017). So far, few studies have examined what digital transformation requires from leadership from a public value lens (Andrews Citation2019).

The aim of this study is to further refine the theoretical concept of digital leadership by exploring what leadership dimensions are important when local governments adopt new technologies with the aim to generate public value. We first identify digital leadership dimensions based on public value theory (Moore Citation1995), leadership literature (Bolman and Deal Citation2017; ‘Hart and Tummers Citation2019; Van der Wal Citation2017) and the digital transformation literature (Meijer and Grimmelikhuijsen Citation2021; Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). Using these dimensions as a heuristic framework to interpret the lived experiences of public professionals and experts, we analyse how local city managers across the Netherlands are leading their organisation during the digital transformation and what is expected from them. We focus on the role of city managers as public leaders because city managers have a leading role within local government and are responsible for civil service. They have an important bridging function between politics, administrative structures and processes, policy goals, action plans, and new developments such as new digital technologies (Meijer and Thaens Citation2010; Streib and Navarro Citation2008; Van der Wal Citation2017; Van Wart et al. Citation2019). The results of this qualitative study contribute to the scientific debate on leadership and digital transformation and provide practical insights and guidelines for city managers.

2. Digital transformation and leadership

In the last decade, local governments are increasingly adopting different types of digital technologies such as, algorithms, artificial intelligence and Big Data that fundamentally transform internal processes and external interactions with stakeholders (Busuioc Citation2021; Gong, Yang, and Shi Citation2020). This digital transformation comes with opportunities for local government organisations such as economic and social value, the improvement of public services, and solutions for wicked problems (Cath Citation2018; Kitchin Citation2014; Meijer Citation2018; Mergel, Rethemeyer, and Isett Citation2016). For example, sensors are used by local governments for crowd control and to measure the weight and speed of vehicles on roads, thereby providing input for maintenance and safety measures by government.

At the same time, the digital transformation challenges the current forms, values, and practices of government organisations. To illustrate this, various local governments in the Netherlands used a machine-learning algorithm to detect welfare fraud. Initially, there was support for this system among government officials. However, in early 2020 the District Court judged that the system was ‘discriminatory’ and ‘not transparent’. Vulnerable citizens, often with a migrant background, were unfairly profiled as suspects of welfare fraud (Meijer and Grimmelikhuijsen Citation2021). Public values, like inclusion, non-discrimination and transparency, privacy and fairness are at the heart of these discussions (Andrews Citation2019; Busuioc Citation2021; Cath Citation2018; Giest and Samuels Citation2020; Kitchin Citation2014; B. Mittelstadt Citation2016; Mergel, Rethemeyer, and Isett Citation2016; Ruijer et al. Citation2023). Several scholars indicate that leadership is needed for coping with these changes and challenges (Andrews Citation2019; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019).

Leadership within the public sector has extensively been studied and there are many definitions of leadership. Sancino and Hudson (Citation2020, 703) define leadership as ‘providing direction and meaning that produce followership (action)’. According to ‘t Hart and Tummers (Citation2019, 6), public leadership is ‘a process of influencing people to think or act differently concerning public issues from what they would otherwise have done’. A leader can influence the behaviours of organisation members to improve quality, performance, and services (Hsieh, Chen, and Lo Citation2015). In addition, leadership requires active scanning and sensemaking of changes in the context in which public organisations and networks operate (Noordegraaf, Geuijen, and Meijer Citation2011; Van der Wal Citation2017). In the context of the digital transformation, Peng (Citation2021) argues that we need to rethink and reconceptualise leadership. The digital transformation involves ‘new styles of leadership, new decision-making processes, different ways of organizing and delivering services’ (Gil-Garcia, Dawes, and Pardo Citation2018, 633).

Recently, some scholars have conducted studies on what the digital transformation implies for public leadership. These studies mainly focus on different attributes, competencies, or roles of digital leadership. To illustrate, Peng (Citation2021) distinguishes four attributes of digital leadership in state governance in China that include digital insight, digital decision-making, digital implementation, and digital guidance. Pittaway and Montazemi (Citation2020) focus on what know-how is necessary for public managers responsible for the implementation of the digital transformation. Know-how is the tacit knowledge that enables public managers to enhance new technology enabled organisational processes. In related strands of literature there also has been some attention for leadership. To illustrate this, in a smart city context Sancino and Hudson (Citation2020) analyse leadership and identify four different modes of leadership related to civic, democratic, business, and technical purposes. In the e-government literature, Van Wart et al. (Citation2019) identify competencies of e-leadership that include e-communication skills, e-social skills, e-team building skills, e-change management skills and e-technological skills. Hsieh et al. (Citation2015) examine the role of leadership in the adoption of online services in Taiwan. They measure the perceived style of leadership and conclude that in an innovative context such as e-government, leaders benefit from instituting a transformational style of leadership. Whereas these studies have led to interesting general insights into modes, attributes, competencies, and roles of digital leadership, they do not explicitly conceptualise digital leadership in relation to the creation of public value.

The notion of public value in relation to new technologies and strategies has increasingly attracted the attention of both practitioners and public administration scholars (Andrews Citation2019; Bannister and Connolly Citation2014; Castelnovo Citation2013; Cordella and Bonina Citation2012; Criado and Gil-Garcia Citation2019; Panagiotopoulos, Klievink, and Cordella Citation2019; Twizeyimana and Andersson Citation2019). In line with the work of Andrews (Citation2019) we use a public value lens to analyse digital leadership. However, whereas Andrews (Citation2019) focuses on a specific technology, algorithms as wicked problems, we focus on the digital transformation in general. Moreover, Andrews (Citation2019) focuses on ethical issues and public values related to algorithms that affect governance and regulation, while our study focuses on city managers who are leading their organisation during the digital transformation. Furthermore, we aim to further refine the theoretical concept of digital leadership by exploring what leadership dimensions are important in the context of the digital transformation.

3. Digital leadership from a public value perspective

In this study we use the public value framework by Moore (Citation1995) for exploring different dimensions of digital leadership. Moore developed his strategic triangle, consisting of a value-based strategy, legitimacy and capacity, for public leaders to help them make sense of the strategic challenges and complex choices they faced (Bennington and Moore Citation2011; Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg Citation2014). According to Bryson et al. (Citation2014), the strategic triangle is an easily understandable heuristic guide to practical reasoning for public managers. Whereas Moore’s (Citation1995) seminal work does not directly account for the digital transformation, several scholars (Andrews Citation2019; Panagiotopoulos, Klievink, and Cordella Citation2019) argue, that the framework also provides a solid foundation to examine the digital transformation in public management.

3.1. Value-based strategy

According to Moore (Citation1995) a value-based strategy refers to a strategy in which public leaders clarify and specify the strategic goals and public value outcomes, which are aimed for in each situation. The digital transformation is often approached from a technical perspective, but the adoption of digital technologies also requires important strategic decisions, for example how to create added value such as safety and transparency for society with technology (Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020; Streib and Navarro Citation2008). According to Pittaway and Montazemi (Citation2020), the digital transformation therefore requires a new vision from digital leaders; they must break from the past and develop a fresh vision with revised norms and values backed up with power and status that provides a strong reinforcement of the digital transformation. They argue that this implies for top management such as city managers that they ‘usher in a new cognitive framework by championing a new vision for the organization’s future that raises aspirations, by generating enthusiasm for a new approach to achieve the vision, and by highlighting the gaps between existing organisational arrangements and those necessary to achieve the new vision’ (Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020, 3). Furthermore, a value-based strategy on digital transformation can provide a dialogue with a dynamic and ambiguous landscape of stakeholders (Van der Wal Citation2017). As, Sancino and Hudson (Citation2020) point out, digital leadership involves democratic processes and decisions affecting a city and its citizens, public-private partnerships and communities. Hence, the value-based strategy implies for city managers that they develop a strategy on how to create value with digital developments in a complex landscape of stakeholders.

3.2. Legitimacy

The second process necessary for the creation of public value according to Moore (Citation1995) is legitimacy. Legitimacy refers to the creation of an authorising environment necessary to achieve the desired outcome (Hinings, Gegenhuber, and Greenwood Citation2018; Moore Citation1995). Building legitimacy is a necessary part of strategic public management and can include a broad range of stakeholders including, lawmakers, regulators, businesses, interest groups and citizens (Andrews Citation2019). Andrews (Citation2019) points out that specific actions need to be undertaken for an authorising environment such as a clear mobilising narrative, the endorsement of experts and cross-party political endorsements (Andrews Citation2019). According to Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer (Citation2022), legitimacy is generated when these actions are in line with the shared norms and values of a community (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). However, because of the transformational and disruptive nature of digital technologies, existing values, norms and practices are often challenged and could result in push back from internal and external stakeholders (Hinings, Gegenhuber, and Greenwood Citation2018). Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer (Citation2022) use the distinction input, throughput and output legitimacy to assess the challenges of digital technologies. They discuss how algorithmic decision-making may lack democratic decision-making and oversight (threatening input legitimacy), may violate with procedural and legal requirements (threatening throughput legitimacy) and potentially produces outcomes that misalign with public values (threatening output legitimacy). The authors argue that input legitimacy will increase if stakeholders’ preferences have been translated through democratic processes in the design and use of digital technologies. Throughput legitimacy will increase if digital technologies are realised by adhering to legal and fair process requirements. Finally, output legitimacy will increase if the use of digital technologies contributes to the values that are considered important by stakeholders (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). In sum, city managers, need to create an environment for the digital transformation that considers the three different forms of legitimacy.

3.3. Capacity

The third process that Moore (Citation1995) distinguishes is building operational capacity. Public leaders must build operational capacity or resources (finance, staff, skills, technology), both inside and outside of the organisation that are necessary to achieve the desired public value outcomes (Bennington and Moore Citation2011). It requires mobilising the will and capacity of members and stakeholders to change their ways of thinking, organising and acting (Kotter Citation2008). Bolman and Deal (Citation2017) describe strategies and characteristics needed in public leaders for building capacity. These strategies are focused on how public leaders can expand their options and enhance their effectiveness. They distinguish four frames for organisational change and capacity building that according to Meijer et al (Citation2022) are relevant for the digital transformation. The structural frame focuses on the architecture and the design of technological systems. The human resources frame emphasises an understanding of people with their strengths, skills, emotion, and fears (Bolman and Deal Citation2017). Digital leadership is about motivating personnel (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022). The digital transformation requires a change of mindset and competencies of public servants (Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). Digital leaders need to stimulate the development of digital competencies of public servants, and need to develop digital competencies themselves (Dingelstad, Borst, and Meijer Citation2022; Sancino and Hudson Citation2020; Streib and Navarro Citation2008). The political frame sees organisations as competitive areas characterised by scarce resources and competing interests (Bolman and Deal Citation2017). Digital leadership is therefore also about, managing conflict (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022). This implies for digital leaders that they are aware of the different interests and know how to accomplish the desired public value outcomes. Finally, the symbolic frame focuses on issues of meaning and faith (Bolman and Deal Citation2017; Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022). This frame adds that digital leadership is also about providing meaning to people (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022). It implies that digital leaders pay attention to the cultural aspect of the organisation: for example, by giving new digital possibilities a place in communication expressions, by creating time for reflection and deliberation about digital changes and the uncertainties and dilemmas that arise. Digital leaders should be able to switch between these four frames and need to consider, the structural, human resources, political and symbolic frames for capacity building (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022).

3.4. Digital leadership dimensions

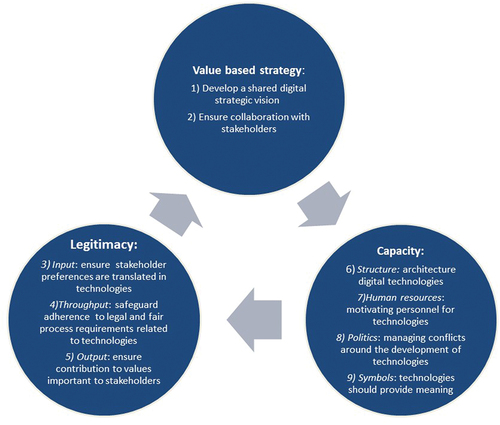

Building upon public value theory (Moore Citation1995), leadership literature (Bolman and Deal Citation2017; ‘; T Hart and Tummers Citation2019; Van der Wal Citation2017), we define digital leadership in this study as providing direction and meaning regarding the digital transformation in local governments in such a way that it leads to public value and legitimate usage. Based on the three foundations of Moore’s strategic triangle we can identify nine underlying dimensions of the digital leadership concept (see ). Digital leadership implies 1) developing a value-based digital strategy 2) in collaboration with other stakeholders. It requires that an environment is created that supports this value-based strategy focused on the dimensions of 3) input, 4) throughput and 5) output legitimacy (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). Finally, digital leadership implies building an organisation that can realise this value-based digital strategy, thereby considering the dimensions of 6) structure, 7) human resources, 8) politics, and 9) symbols (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022).

Figure 1. Nine digital leadership dimensions based on Moore’s strategic triangle (Citation1995).

In the following section, we use these dimensions as a heuristic framework to examine in practice how city managers as digital leaders are leading digital transformation in local governments and what is expected from them.

4. Methodology

This study used an exploratory interpretative qualitative research design that consisted of 28 interviews in total. A qualitative approach fits well with exploratory studies (Creswell Citation2013; Ospina, Esteve, and Lee Citation2018). After all, the aim of our research is to explore and refine the theoretical concept of digital leadership based on our heuristic framework and the lived experiences of public professionals in local government. For the data collection and analysis, we followed the guidelines for qualitative research as identified by Ospina et al. (Citation2018). In total 28 interviews were conducted. 18 interviews were conducted in 7 cities in the Netherlands (See ) . The Netherlands ranked third in 2022 on the EU Digital Economy Index Society that measures connectivity, digital skills, and e-government. In each city, the city manager, a public servant and either a mayor or alderman were interviewed. In this way, we studied digital leadership from multiple realities (Creswell Citation2013): both from the city managers and from the perspective of professionals who work with them. The alderman or mayor, (depending on whom has the digital transformation in their portfolio), was interviewed from the perspective of the city council. Unfortunately, in the two largest cities the aldermen were not available for an interview and the same goes for a public servant in the largest city. The respondents were selected based on a combination of purposive and convenience sample (Bryman Citation2012). The respondents worked in small, midsized, and big cities. The study considers the number of inhabitants and thus the size and capacity of the government organisation for a representative reflection of the Dutch municipalities. Only the smallest cities are not part of the study. Given their number of tasks and limited capacity, they have often assigned the digital themes to a larger city in the Netherlands.

Table 1. Overview of the selected cities: number of inhabitants and respondents.

In addition, 10 experts were interviewed to validate the results from the interviews held with the public servants. The experts consisted of university professors, directors of Dutch knowledge organisations and special advisors to the government. All 28 interviews were recorded and transcribed.

The 18 interviews with public professionals consisted of Behavioral Event Interviews (BEI’s) (Spencer and Spencer Citation1993). This technique has an exploratory purpose and is often used for qualitative competencies studies (Dingelstad, Borst, and Meijer Citation2022; Getha-Taylor Citation2008; McClelland Citation1998). BEI fits well with our research that focused on better understanding what city managers do and need, to lead their organisation during the digital transformation. We followed the BEI interview protocol (Dingelstad, Borst, and Meijer Citation2022; Getha-Taylor Citation2008) to enhance replication of this study (Bryman Citation2012); after an introduction, the interviewer asked the respondent to describe their most important tasks and responsibilities in general and in relation to the digital transformation. Subsequently, the interviewer asked the respondent to describe in detail some of the most important situations experienced on the job; more specifically, both successes and challenges or failures related to the digital transformation. The interviews with city managers focused on what the digital transformation implies for their leadership (see appendix A). The interviews with the other public servants addressed how they experienced the digital leadership of their city manager and what they expected from a digital leader in their daily practice (see Appendix B).

The interviews with the experts consisted of semi-structured interviews that also focused on what the digital transformation implies for leadership from city managers. For example, questions about whether and how digital leadership is different from leadership, what digital leadership implies and what city managers may need regarding the digital transformation (see Appendix C).

Data analysis was done by means of NVivo, using an abductive approach (Ashworth, McDermott, and Currie Citation2019), with regular iteration between data and theory. An abductive approach combines deductive and inductive theorising (Ashworth, McDermott, and Currie Citation2019). We used a thematic analysis (Bryman Citation2012). The three processes; value-based strategy, legitimacy and capacity building, were used as a priori codes that guided the coding process (Creswell Citation2013. Following, we coded and grouped the statements in the transcripts of the BEI interviews according to these ‘prefigured codes’ but also identified additional codes that emerged from the statements in the transcripts (Creswell Citation2013). To illustrate this, an additional code that emerged was ‘experimentation and learning’ as part of the value based- strategy process. Next, the coding tree was further refined by identifying subthemes that emerged from the codes identified in the transcripts based on already identified and new dimensions within the three processes (Bryman Citation2012). We also analysed whether there were differences in responses between the different cities in terms of their size and between the different public professionals. To enhance the dependability of our study (Bryman Citation2012) we kept records of the interview transcripts and data analysis in an accessible manner.

5. Results

5.1. Value based strategy

According to our theoretical model, city managers are expected to work on a shared value-based strategic vision with stakeholders. In our interviews, experts underscored the importance of a vision. They indicated that city managers must take leadership concerning the digital transformation. The digital transformation is a strategic task, not an operational task according to the experts. However, according to experts, most city managers fail to connect the digital transformation to public problems, policies and to public values. They fail to integrate the transformation in every aspect of the organisation. An expert:

Reflection is step 1, but it barely happens. One starts with the technology, a random technology is chosen such as data or Blockchain, ok let’s do something with this technology. It is technology driven instead of reflecting on what the technology can mean for public problems and public values.

City managers themselves acknowledged that they have an important leadership role in their organisation regarding the digital transformation but confirmed that in practice there often is no strategic vision on how technology can contribute to a solution for public problems. According to city managers and aldermen this is because of the hectic pace of everyday life, which means that they are pressed for time. At the same time, city managers mentioned that they lack the insight or knowledge on which strategic questions to ask. Asking the ‘right questions’ is challenging because they cannot foresee the (long-term) consequences of the technological developments. Or as one of the aldermen said:

The city manager is expected to play a strategic role, gain insight into important developments in this area and continue to ask relevant questions. (…). At the same time, this is a dilemma. It requires from someone who does not know exactly what the consequences of all technological developments are to reflect on the question: what do these developments mean for the role of the government in the future? (…). If you would have asked someone in the 1920’s, how can I drive faster? Then they would have answered that you need faster horses. Instead of answering that you need a car.

A mayor, an alderman and several city managers also mentioned the importance of collaboration with external stakeholders. They considered this as part of the task of the city manager but indicated that this doesn’t get enough attention in practice. According to them, collaboration with stakeholders is important for mutual learning and for sharing information. Societal issues do not stop at the boundaries of the organisation.

Public servants also expect that city managers have a vision and ambition regarding the digital transformation. In practice most city managers fail to do this according to the public servants. In addition, public servants indicated that to implement the vision they expect city mangers to offer them more room to experiment including living labs and innovation initiatives:

For me it is important that we get room to experiment. Even if the budget is tight. Even if data leaks and risks are mentioned in the press. This should not paralyze us or lead to anxiety. That is a role of the city manager.

Hence, the respondents confirmed that it is important for digital leaders to perceive the digital transformation as a strategic task that requires a clear vision and ambition in collaboration with stakeholders, connected to public problems and values that are important for the city. However, city managers fail to do so in practice because they lack the time and knowledge to develop a strategic value-based vision. For the development and implementation of such a vision, it is expected by public servants that city managers stimulate experimentation and joint learning.

5.2. Legitimacy

Almost all respondents emphasised legitimacy as a dimension of digital leadership. Most respondents referred to issues related to the dimension throughput legitimacy. They indicated that digital practices must be in accordance with the legal rules, (ethical) principles and guidelines. They referred to the value of privacy. Respondents stressed the importance of compliance with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enhancing privacy awareness within the organisation, and the prevention of cyber-attacks:

Cities are not the most efficient organizations in the world, but we should be the most reliable organizations. Data and information are our core business and the way we protect privacy highly determines our reliability (a city manager).

Almost all respondents indicated that city managers put protecting privacy on the agenda and that they made sure that it stays on the agenda. Most city managers know the GDPR and pay attention to privacy in practice. Next to privacy, mayors, aldermen, city managers, public servants and experts, mentioned the importance of other values such as transparency and accountability. City managers also referred to ethical principles. However, most of the city managers indicated that they did not know exactly which ethical principles are used in daily practice regarding, for example algorithms in their organisation. They also indicated that these principles might not be well embedded in the organisation:

If asked whether I think that all the people involved in the adoption of technology make conscious choices, then I think the answer is no.

Regarding input legitimacy, respondents referred to inclusion. Most of the city managers indicated that they pay attention to those people who do not have the capability to participate in the changing digital society. As one city manager mentioned:

The legitimacy of government is largely determined by the extent to which the government serves everyone in society.

According to two experts and several mayors, aldermen and city managers, municipalities not only offer digital services, but in practice they also ensure that face-to-face meetings with external stakeholders such as citizens are possible. Furthermore, a few experts and alderman also mentioned that digital leadership means paying attention to the digital resilience of citizens. To illustrate this, one alderman indicated that they had organised an evening to educate citizens about cyber security. However, this example was an exception, the interviews showed that in practice little attention was paid by the city manager to digital resilience of citizens.

Finally, a few respondents referred to output legitimacy. Especially experts indicated that city managers in both the organisation, and in advising the mayor, alderman and council, do not pay enough attention to the impact of technologies. An expert said:

Digital leadership is the capability to constantly reflect on what the impact is of digital developments on public values. Thus, how the city manager can make sure that the outcome is reliable and does not violate values that are important by stakeholders, such as transparency and equality.

Hence, in general, respondents confirmed the importance of legitimacy. Respondents pointed out several dimensions of digital leadership, which focused on privacy (throughput legitimacy) and inclusion (input legitimacy). The interviews revealed that these were the aspects that most of the city managers pay attention to in their daily work. Especially experts stressed the importance of output legitimacy and indicated that the role of the city manager is currently too limited. Additionally, respondents indicated that digital leaders have a role in the ethical implications of technologies. However, city managers do not yet pay enough attention to this aspect in practice.

5.3. Capacity

Regarding capacity building, we analysed our findings in relation to the four frames: structure, human resources, politics, and symbols. Regarding structure, several city managers, public servants, and experts stressed that city managers need to pay far more attention to the governance of digital technologies in their own organisations and to the outsourcing of services than they currently do. Several cities, small, midsized, and big cities, use external services and applications. According to them, contracts with external providers should not only be the responsibility of IT departments, but also of the city manager. Digital leadership means ensuring that conditions when tendering digital systems include ownership, responsibilities, and entitlements. At the same time, they indicated that city managers do not have enough knowledge to properly provide direction for the outsourcing of digital services:

One city manager confirms this:

In this organization we have a large ICT department. Increasingly, in the future we will become a coordinating department. (…). This implies that we will increasingly outsource our basic infrastructure and that we will collaborate with external parties. It is essential that we build an organization that has the knowledge necessary to coordinate and manage external parties. That is the switch we are currently making.

By contrast, several experts indicated that cities should not become too dependent of companies and city managers should develop knowledge inside their organisation. Too often the choices regarding these structures in terms of outsourcing or not were made by the chief information officer instead of the city manager, according to public servants and experts.

Another theme discussed by experts and public servants was that digital leadership required more attention of the city manager for the quality and reliability of data, this turned out not to be the case in almost all cities in this study. It is not just about the data itself but also about the usage of data:

If the data is not accurate and does not measure what you would like to measure than they should not be used (an expert)

Regarding human resources all respondents stressed the importance of knowledge and skills of city managers themselves as public digital leaders:

I must know how this impacts society. I must understand how it changes the organizations and understand where decisions are made when digital technologies are developed and which consequences these decisions have. In order to have that conversation with technological experts I must have some knowledge myself (a city manager).

However, almost all respondents mentioned that city managers as digital leaders must further develop their digital competencies. In addition, the respondents indicated that city managers must stimulate, more than they currently do, the digital competencies of public servants. Public servants must know how to use the technology in such a way that it is of added value for societal issues and meets important public values such as safety and transparency. Not everyone needs to know and be able to do everything according to the respondents, but public servants must learn and be aware of which expertise is required for which digital theme and be able to put together a multidisciplinary team with knowledge of policy, ethics, data analysis and politics. Several city managers therefore indicated that the Human Resource department should provide opportunities for public servants in terms of education and training. However, this barely happens in practice and most city managers do not stimulate this either:

If you look at the development of public servants in general than we are very generous in terms of personal development, career progression and knowledge development (…) but not a lot happens in terms of digital skills development (a city manager).

City managers also indicated that the digital transformation has implications for personnel recruitment and hiring policies. The digital transformation leads to new jobs but may also lead to the disappearance of existing jobs. However, there is little attention of the city manager for these effects in daily practice.

Regarding politics, city managers as digital leaders, should have an eye for different interests within local government, according to alderman, mayors and experts. However, there is too little attention for this by city managers in practice. One expert:

Because they [politicians] have a lack of knowledge regarding the new digital developments city managers have to be able to explain clearly what they are doing, what the different interests are and what choices politicians can make.

According to the mayors and aldermen interviewed, the digital transformation is not yet high on the political agenda. Politicians are often concerned with issues of today and perceive the digital transformation as a technical issue. Therefore, city managers need to put the digital transformation more on the agenda than they currently do and make sure that it stays there: by connecting the digital transformation to policy issues and public values, and by involving politicians earlier in the process. Furthermore, too often the policy briefings and other documents for politicians are too technical and do not explicitly pay attention to possible consequences for citizens. A mayor:

We started a project on playgrounds. Based on data analysis we concluded that we could merge some smaller playgrounds into a bigger one and move a few playgrounds to a different area. The analysis was based on demographics and maintenance data. But the resistance to this project among parents led to a full public gallery during a council meeting. The city council then backed the parents. We used data from a too technical perspective.

Regarding symbols, it is important according to city managers that they need to communicate clearer (more than they do now) within the organisation that work will change due to digital developments. City managers indicated that many public servants see the digital transformation as a threat rather than an opportunity and are afraid that their work will disappear.

We now have a robot at the entrance. Then you see the reception staff thinking ‘what does it mean for us and our jobs (a city manager).

Experts therefore emphasised that city managers more than they currently do, must be aware of this. Introducing new symbols by the city manager, for example by participating in a data project in order to learn, or introducing an award for the best value driven data project, can make the changes more visible and recognisable.

Digital transformation is not possible without a mental transformation (an expert).

Hence, our findings confirm that the dimensions, structure, human resources, politics, and symbols, affect capacity building for digital transformation. Regarding the dimension structure, the quality and reliability of data are mentioned as aspects that require more attention from city managers. Furthermore, city managers must pay more attention to the outsourcing of data and digital systems. Human resources are stressed in all interviews. Respondents emphasised that city managers miss the knowledge and competencies of digital leaders and need to further develop their digital competencies and stimulate the development of digital competences of public servants. In addition, city managers need to ensure that policy issues and the political agenda are more connected with the digital transformation. City managers need to involve politicians more and earlier in digital projects. Finally, our findings demonstrate that city managers spend too little time on the cultural aspect of the organisation, the habits and customs that are changing by the digital transformation and the uncertainties and dilemmas that arise for public servants.

6. Analysis and discussion

The digital transformation is changing the landscape of public management (Bannister and Connolly Citation2014; Criado and Gil-Garcia Citation2019; Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022). We focused on what the digital transformation requires from city managers when their organisation adopts digital technologies aimed at generating public value (Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). Based on Moore’s strategic triangle (Citation1995), we identified nine dimensions of digital leadership. Based on our empirical findings that assesses what city managers do in practice and what is expected from them, we can further refine these dimensions. Regarding the first foundation, a value-based strategy, our empirical findings show the importance of a vision regarding the digital transformation (dimension 1) connected to public problems and public values and the importance of collaboration with stakeholders to better understand needs of the users of the technologies (dimension 2). However, in practice, most city managers in this study did not discern or define what a value-based vision might be. A shared vision provides a common mindset on which to build a constructive dialog with internal and external stakeholders (Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020). At the same time, developing a value-based vision is expected from them but also challenging. As Andrews (Citation2019) notes, public (digital) leaders are creating public values in a new field, in which public value theory might not yet be specifically cited as underpinning their work. Our findings also indicated that for the development and implementation of a vision, digital leaders are expected to encourage and allow for experimentation and joint learning. These findings are in line with studies that stress an open iterative approach to digital innovation through living labs and innovation platforms that bring together a broad range of internal and external stakeholders to co-create value, continuous learning and finding solutions for local public problems (Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg Citation2014; Sancino and Hudson Citation2020).

Second, regarding legitimacy, even though respondents stressed the importance of legitimacy, in their daily practice, city managers mainly paid attention to throughput legitimacy (dimension 4). This is problematic because legitimacy is critical to governments as it provides a basis for the acceptance of government decisions (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). As Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer (Citation2022) indicate a lack of attention to input legitimacy (dimension 3) may lead to a lack of democratic control. Political oversight might be lacking in the council and in the local government organisations if digital transformation is not put on the agenda. A lack of attention to input legitimacy may also lead to a lack of responsiveness of decision-making (lack of translation of citizen’s voices in technology). Moreover, a lack of attention to output legitimacy (dimension 5) by digital leaders may lead to ineffective, inefficient technology and undesirable outcomes (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). Furthermore, even though city managers focused on throughput legitimacy, they focused mainly on the value of privacy, which may lead to blind spots. Public leaders also need to consider other public values such as safety, transparency, fairness, and accountability (c.f. EU Ethics Guidelines for trustworthy AI, Citation2019). These values can be conflicting. City managers are expected to have a directing role in managing these value conflicts. However, as Zwanikken and Ruijer (Citation2022) demonstrate there is so far limited attention in both research and practice regarding leadership in relation to managing value conflicts around digital technologies. Their findings stress that public managers, need to lead by example, empower personnel, facilitate an open dialogue about ethical dilemmas, implement ethical codes and ethical committees, and stimulate training, monitoring, and control, in local government (Zwanikken and Ruijer Citation2022).

Third, our findings highlight that capacity building requires digital leadership that pays attention to data governance (such as outsourcing, data quality and reliability) (dimension 6), stimulate the development of digital competencies in the organisation and stimulate working in multidisciplinary teams (dimension 7), ensure that the digital transformation is connected to policy issues and the political agenda (dimension 8), and communicate about the transformation and provide opportunities for recognition, rewards and development (dimension 9). These are not technical issues, but ‘chefsache’. This means that the city manager must be aware of and have knowledge about the digital developments, know how to ask the right questions, can think critically about the consequences and, based on this, make conscious choices how to build the capacity. Our findings are largely in line with other studies (Dingelstad, Borst, and Meijer Citation2022; Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022; Van der Wal Citation2017), who stress the importance of digital skills, change management, political astuteness, and team building skills for digital leadership. Dingelstad et al. conclude that not all competencies are new. Similarly, for some leadership aspects, digital developments require something new from the city manager. This includes ensuring a transparent and verifiable set of data and algorithms, developing digital literacy, and attention to the legitimacy of data practices. For other leadership aspects, it is sufficient to retain or strengthen existing qualities, such as a learning orientation, political astuteness, setting a good example and realising a shared perspective. However, what our findings add, is that currently most of the city managers lack the knowledge and these competencies. This is problematic. As Meijer et al. (Citation2022) indicate that whereas it is common sense that public leaders require a basic understanding of financial matter or human resources, the realisation of the need for a basic understanding of digital technologies is only slowly sinking in. Since no public organisation can function without digital technologies, leaders need to acquire understanding of these technologies and connect them to their familiar world of human and financial resources (Meijer, Ingrams, and Zouridis Citation2022).

Fourth, our findings provided insights into digital leadership from different angles, leading to a more integrative perspective on leadership. To illustrate this, experts stressed that city managers need to develop knowledge and skills related to digital transformation and that they must connect the digital transformation to public problems and public values and integrate it into every aspect of the organisation. The aldermen and mayors emphasised that city managers need to put digital transformation more often on the political agenda by connecting digitalisation with policy issues. Public servants expect guidance from the city manager and room to experiment. City managers know that they must take leadership but are searching for their role in the digital transformation. A lack of time, knowledge, and competencies in digital technologies prevents them from taking digital leadership.

Finally, this study has also some limitations. The study was conducted in a local context and focused on what digital transformation implies for the leadership of the city manager. The digital transformation at the national or international government in other countries may pose other challenges for leadership, which could result in additional dimensions of leadership. Therefore, further research is necessary in other contexts. Furthermore, although this study was based on a limited but diverse local government in the Netherlands, the smallest towns were not included in this city. Unlike Feeney et al. (Citation2020) who find differences in their findings for smaller cities, in our study, the size of the city did not appear to influence the results; in big, midsized, and small cities, the same dimensions emerged. Feeney et al. (Citation2020) find differences in the maturity of technology adoption, whereas managing the adoption might require the same for different city sizes. Nevertheless, more research is necessary to determine the effect of city size and whether the stage of digital transformation maturity matters for digital leadership (Kafel, Wodecka-Hyjek, and Kusa Citation2021; Lee and Kwak Citation2012). Additionally, this study used a qualitative exploratory research design consisting of BEI and expert interviews in a Dutch context that limits the transferability (Bryman Citation2012) of this study. Future research is needed that focuses on the construction and validation of measurement scales of our identified dimensions via for example quantitative surveys and behavioural experimental quantitative studies (Tummers and Knies Citation2016) in different contexts. This may result in a different outcome regarding the leadership dimensions identified in this study.

7. Conclusion

For many governments, the digital transformation is as much about the technologies as it is about creating an organisational environment in which the transformation can take place (Curtis Citation2019; Gong, Yang, and Shi Citation2020; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). This has implications for leadership. Technological change remains understudied in public administration, while the technological challenges that governments face are growing in complexity (Andrews Citation2019). So far, few empirical studies have focused on what the digital transformation requires from leadership in the public sector (Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019; Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020).

This study contributes to the academic literature on the digital transformation by identifying what leadership dimensions are important for city managers who are leading their organisation during the digital transformation. We identified dimensions of digital leadership using a public value lens (Moore Citation1995) and by building upon the leadership (Bolman and Deal Citation2017; ‘; T Hart and Tummers Citation2019; Van der Wal Citation2017) and digital transformation literature. We used these dimensions as a heuristic framework to analyse how city managers in practice across the Netherlands are leading the digital transformation aimed at generating public value and legitimate usage. Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of analysing digital leadership from a public value lens. The digital transformation introduces new ways of working, and core organisational processes are redesigned (Mergel et al. Citation2018; Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019; Pittaway and Montazemi Citation2020). Failure to address a value-based vision, legitimacy and capacity by digital leaders in this transformation process may entail the risk of ineffective policy, unintended consequences and eventually that the public’s trust in local government is damaged (Grimmelikhuijsen and Meijer Citation2022). Therefore, city managers must be aware of digital developments, develop a vision, involve politicians more and earlier, have knowledge about the functioning of the technologies and the use of data, be able to think critically about the consequences and impact of technologies and, on that basis, make conscious choices when using these technologies to improve the quality of life. At the same time, our study demonstrates that currently, city managers lack the knowledge and competencies to put this into practice.

For practice, the digital leadership dimensions can provide guidance to city managers who are responsible for providing direction and meaning regarding the digital transformation. Training and personal development for city managers could be one avenue to develop knowledge and competencies. The digital leadership dimensions in this study can provide a foundation for the training and personal development of city managers, which may help city managers make their organisations ready for the digital age.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2024.2363368

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Martien Branderhorst

Dr. Emma Martien Branderhorst is an academic fellow at the Utrecht University. She is also one of the general directors at the municipality of The Hague and involved in the sustainable improvement of outdoor (digital) space. Furthermore, she is a member of the Council for Public Administration. This council is an independent advisory body of the Dutch government and parliament.

Erna Ruijer

Dr. Erna Ruijer is an assistant professor at the Utrecht University School of Governance. Her research interests include the digital transformation in the public sector, social equity and inclusion in the digital society, government transparency and open government data.

References

- Andrews, L. 2019. “Public Administration, Public Leadership and the Construction of Public Value in the Age of the Algorithm and ‘Big data’.” Public Administration 97 (2): 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12534.

- Ashworth, R. E., A. M. McDermott, and G. Currie. 2019. “Theorizing from Qualitative Research in Public Administration: Plurality Through a Combination of Rigor and Richness.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 29 (2): 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy057.

- Bannister, F., and R. Connolly. 2014. “ICT, Public Values and Transformative Government: A Framework and Programme for Research.” Government Information Quarterly 31 (1): 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.06.002.

- Bennington, J., and M. Moore. 2011. “Public Value in Complex and Changing Times.” In & M. Moore, Public Value. Theory and Practice, edited by J. Benington, 1–30. New York City, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bolman, L., and T. Deal. 2017. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choices and Leadership. 3rd ed., Vol. 6th ed. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bryson, J., B. Crosby, and L. Bloomberg. 2014. “Public Value Governance: Moving Beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management.” Public Administration Review 74 (4): 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238.

- Busuioc, M. 2021. “Accountable Artificial Intelligence: Holding Algorithms to Account.” Public Administration Review 81 (5): 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13293.

- Castelnovo, W. 2013. “A Stakeholder Based Approach to Public Value Creation.” Proceedings of 13th European conference on Egovernment, Como, Italy. 94–101.

- Cath, C. 2018. “Governing Artificial Intelligence: Ethical, Legal and Technical Opportunities and Challenges.” Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 376., 20180080. The Royal Society Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0080.

- Cordella, A., and C. Bonina. 2012. “A Public Value Perspective for ICT Enabled Public Sector Reforms: A Theoretical Reflection.” Government Information Quarterly 29 (4): 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.03.004.

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications.

- Criado, J., and J. Gil-Garcia. 2019. “Creating Public Value Through Smart Technologies and Strategies. Form Digital Services to Artificial Intelligence and Beyond.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 32 (5): 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-07-2019-0178.

- Curtis, S. 2019. “Digital Transformation - the Silver Bullet to Public Service Improvement?” Public Money & Management 39 (5): 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1611233.

- Da Rosa, I., and J. De Almeida. 2017. “Digital Transformation in the Public Sector: Electronic Procurement in Portugal.” In Digital Governance and E-Government Principles Applied to Public Procurement, edited by R. Shakya, 99–125. IGI Global.

- Dingelstad, J., R. Borst, and A. Meijer. 2022. “Hybrid Data Competencies for Municipal Civil Servants: An Empirical Analysis of the Required Competencies for Data-Driven Decision-Making Making.” Public Personnel Management 51 (4): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/00910260221111744.

- European Commission. 2019. “Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence.” Retrieved from Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI | FUTURIUM | European Commission europa.eu.

- Feeney, M., F. Fusi, L. Camarena, and F. Zhang. 2020. “Towards More Digital Cities? Change in Technology Use and Perceptions Across Small and Medium-Sized US Cities.” Local Government Studies 46 (5): 820–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1690993.

- Frick, N., M. Mirbabaie, S. Stieglitz, and J. Salomon. 2021. “Maneuvering Through the Stormy Seas of Digital Transformation: The Impact of Empowering Leadership on the AI Readiness of Enterprises.” Journal of Decision Systems 30 (2–3): 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2020.1870065.

- Getha-Taylor, H. 2008. “Identifying Collaborative Competencies.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 28 (2): 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X08315434.

- Giest, S., and A. Samuels. 2020. “‘For Good measure’: Data Gaps in a Big Data World.” Policy Sciences 53 (3): 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09384-1.

- Gil-Garcia, R., S. Dawes, and T. Pardo. 2018. “Digital Government and Public Management Research Finding the Crossroads.” Public Management Review 20 (5): 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1327181.

- Gong, Y., J. Yang, and X. Shi. 2020. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Digital Transformation in Government: Analysis of Flexibility and Enterprise Architecture.” Government Information Quarterly 37 (3): 101487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101487.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., and A. Meijer. 2022. “Legitimacy of Algorithmic Decision-Making: Six Threats and the Need for a Calibrated Institutional Response.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 5 (3): 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvac008.

- Hinings, B., T. Gegenhuber, and R. Greenwood. 2018. “Digital Innovation and Transformation: An Institutional Perspective.” Information and Organization 28 (1): 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.02.004.

- Hsieh, P., W. Chen, and C. Lo. 2015. “An Investigation of Leadership Styles During Adoption of E-Governemnt Fon an Innovative City: Perspectives of Taiwanese Public Servants.” In Transforming City Governments for Successful Smart Cities. Public Administration and Information Technology, edited by M. Rodriquez-Bolivar, Vol. 8., 163–180. Cham: Springer.

- Kafel, T., A. Wodecka-Hyjek, and R. Kusa. 2021. “Multidimensional Public Sector organizations’ Digital Maturity Model.” Administration & Public Management Review: 37. https://doi.org/10.24818/amp/2021.37-02.

- Kitchin, R. 2014. The Data Revolution. Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures & Their Consequences. London: Sage Publishing.

- Kotter, J. 2008. Force for Change. How Leadership Differs from Management. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Lee, G., and Y. H. Kwak. 2012. “An Open Government Maturity Model for Social Media-Based Public Engagement.” Government Information Quarterly 29 (4): 492–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.001.

- McClelland, D. C. 1998. “Identifying Competencies with Behavioral-Event Interviews.” Psychological Science 9 (5): 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00065.

- Meijer, A. 2018. “Datapolis: A Public Governance Perspective on “Smart Cities”.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1 (3): 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvx017.

- Meijer, A., and S. Grimmelikhuijsen. 2021. “Responsible and Accountable Algorithmization. How to Generate Citizen Trust in Governmental Usage of Algorithms.” In The Algorithmic Society. Technology, Power, and Knowledge, edited by M. Schuilenburg and R. Peeters, 53–66. London: Routledge.

- Meijer, A., A. Ingrams, and S. Zouridis. 2022. Public Management in an Information Age. Introduction to Strategic Public Information Management. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Meijer, A., and M. Thaens. 2010. “Alignment 2.0: Strategic Use of New Internet Technologies in Government.” Government Information Quarterly 27 (2): 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2009.12.001.

- Mergel, I., N. Edelmann, and N. Haug. 2019. “Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews.” Government Information Quarterly 36 (4): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.06.002.

- Mergel, I., R. Kattel, V. Lember, and K. McBride. 2018. “Citizen-Oriented Digital Transformation in the Public Sector.” Proceedings of the 19th annual international conference on digital government research: Governance in the data age, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209281.3209294.

- Mergel, I., R. Rethemeyer, and K. Isett. 2016. “Big Data in Public Affairs.” Public Administration Review 76 (6): 928–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12625.

- Mittelstadt, B. 2016. “Auditing for Transparency in Content Personalization Systems.” International Journal of Communication 10:4991–5002.

- Mittelstadt, B. D., P. Allo, M. Taddeo, S. Wachter, and L. Floridi. 2016. “The Ethics of Algorithms: Mapping the Debate.” Big Data & Society 3 (2): 2053951716679679. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716679679.

- Moore, M. 1995. Creating Public Value. Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge: Harvars University Press.

- Noordegraaf, M., K. Geuijen, and A. Meijer, Eds. 2011. Handboek publiek management. Den Haag: Boom Lemma Uitgevers.

- Ospina, S. M., M. Esteve, and S. Lee. 2018. “Assessing Qualitative Studies in Public Administration Research.” Public Administration Review 78 (4): 593–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12837.

- Panagiotopoulos, O., B. Klievink, and A. Cordella. 2019. “Public Value Creation in Digital Government.” Government Information Quarterly 36 (4): 101421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101421.

- Peng, B. 2021. “Digital Leadership: State Governance in the Era of Digital technology.” Cultures of Science 5 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/209660832198983.

- Pittaway, J., and A. Montazemi. 2020. “Know-How to Lead Digital Transformation: The Case of Local Governments.” Government Information Quarterly 37 (4): 101474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101474.

- Ruijer, E., G. Porumbescu, R. Porter, and S. Piotrowski. 2023. “Social Equity in the Data Era: A Systematic Literature Review of Data-Driven Public Service Research.” Public Administration Review 83 (2): 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13585.

- Sancino, A., and L. Hudson. 2020. “Leadership In, of and for Smart Cities- Case studies from Europe, America and Australia.” Public Management Review 22 (5): 701–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1718189.

- Sarker, M. N., M. Wu, and M. Hossin. 2018. “Smart Governance Through Big Data: Digital Transformation of Public Agencies.” International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ISAIBD), 62–70. Chengdu, China: IEEE.

- Schwarzmuller, T., P. Brosi, D. Duman, and I. Welpe. 2018. “How Does the Digital Transformation Affect Organizations? Key Themes of Change in Work Design and Leadership.” Management Revue 29 (2): 114–138. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2018-2-114.

- Spencer, L., and S. Spencer. 1993. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Streib, G., and I. Navarro. 2008. “City Manager and E-Government Development: Assessing Technology Literacy and Leadership Needs.” International Journal of Electronic Government 4 (4): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.4018/jegr.2008100103.

- T Hart, P., and L. Tummers. 2019. Understanding Public Leadership. London, UK: Red Globe Press.

- Tummers, L., and E. Knies. 2016. “Measuring Public Leadership: Developing Scales for Four Key Public Leadership Roles.” Public Administration 94 (2): 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12224.

- Twizeyimana, J., and A. Andersson. 2019. “The Public Value of E-Government- a Literature Review.” Government Information Quarterly 36 (2): 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.01.001.

- Van der Wal, Z. 2017. The 21st Century Public Manager. London: Macmillan International Higher education.

- Van Wart, M., A. Roman, X. Wang, and C. Liu. 2019. “Operationalizing the Definition of E-Leadership; Identifying the Elements of E-Leadership.” International Review of Public Administration Sciences 85 (1): 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852316681446.

- Zwanikken, P., and E. Ruijer. 2022. “Ethisch leiderschap: Een onderzoek naar de rol van leiderschap bij ethische dilemma’s over datagebruik bij gemeenten. [Ethical Leadership: A Study on the Role of Leadership in Ethical dilemma’s Regarding Data Usage in Local Governments.” Bestuurswetenschappen 76 (1): 27–49. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942022076001003.