ABSTRACT

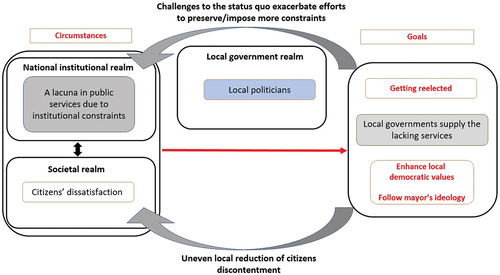

Under which circumstances local governments’ responsiveness to its residents’ preferences overtakes the central government’s accountability for public preferences at the national level in democracies? This study hypothesises that (1) A lacuna in public services at the national level due to institutional constraints, leading to (2) societal dissatisfaction as expressed by public opinion, as well as (3) local politicians in search for re-election, will lead local governments to account for public preferences. We further argue that local governments’ goal in accounting for public preferences is to follow the mayor’s personal ideology as well as enhance democratic values while predominantly improving their political gains. Using a mixed-method design, this study paints on the mechanism behind local initiatives to overcome policy restrictions on three religion-based policies in Israel. It demonstrates that efforts made by local governments to supply the lacking public services are an act of local responsiveness conjoint with political aspirations.

Introduction

The local government is the political strata that is the closest to citizens. Hence, it can sense and identify their changing preferences rather rapidly. Identifying citizens' preferences allows the local government to account for it while providing the public with goods and services they long for. Literature has long identified local government’s alignment with their public’s preferences. It stresses that the benefits of local governments’ service delivery include efficiency and effectiveness as they are geographically closer to the citizenry (Abdullah and Kalianan Citation2008) Afonso and Fernandes Citation2008; García‐Sánchez Citation2006; Ho Citation2002). It also allows local officials to provide solutions to local issues, so that the central government can focus on other, perhaps more nationally-pressing issues (Steiner et al. Citation2018).

Evidently, local governments have proven to be highly efficient and resilient in managing troublesome occurrences, as during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dzigbede, Gehl, and Willoughby Citation2020; Pradana et al. Citation2020; Wayenberg et al. Citation2022), weather disasters (Lowndes and McCaughie Citation2013; Sciulli Citation2018), and in overall emergency planning (Henderson Citation1986; Nicholson Citation2007; Perry and Lindell Citation2003). As opposed to irregular times when local governments supply important services, while supporting/complementing the central government’s efforts, in this study, we draw on day-to-day public services that local government supply, since they recognise a void in the central governmental service provision vis-a’-vis public demands. This void is created due to institutional policy constraints at the national level. Further, we use the case of religion and state in order to show that it can become a constraint to service provision just like any other legal-institutional constraints – making it a paradigmatic case study.

In the context of religion at the local realm, studies have shown the importance of subnational variation of freedom of religion or belief violations in Latin American (Klocek and Petri Citation2023) and the accommodation of minority religious practices in the post-Communist Muslim Republics (Shaykhutdinov Citation2013, Citation2024). These studies, however, did not draw on local governments as the suppliers of public services that are restricted by central governments due to religious constraints.

In this study, we wish to use the Israeli case study to shed light on democracies with religious constraints. Overall, Israeli local governments possess limited autonomy and have been regarded as an extension of the central government (Razin and Hazan Citation2014). Despite neo-liberal public sector reforms since the late 1980s, this centralised control over the local government remains (Ben-Bassat, Dahan, and Klor Citation2016) and further enhanced (Uster and Cohen Citation2023).

Institutionally, Israel incorporates Orthodox Judaism (and no other form of Judaism) into its legal-institutional designs. Indeed, state-religion relations in Israel can be classified as; non-secular, but friendly to democracy (Stepan Citation2000), a state with an established religion, yet contains some characteristics of the religious state, as legislation in several realms, namely Sabbath, education, marriage and Kosher food in the public realm, is religion-based (Kuru Citation2007). Further, according to Fox and Sandler, Israel can be defined as a religious democracy, as most Western democracies do not have full separation of religion and state (Citation2005).

Evidently, due to religious constraints, some acute public services are not supplied by the central government. This, in turn, brings about initiatives by local governments to supply the lack of services while struggling to find ways to do it legally. Hence, we ask: Under which circumstances local governments’ responsiveness to its residents’ preferences overtakes the central government’s accountability for public preferences at the national level in democracies? We hypothesise that, (1) A lacuna in public services at the national level due to institutional constraints, leading to (2) societal dissatisfaction as expressed by public opinion, as well as (3) local politicians in search for re-election, will lead local governments to account for public preferences. We further argue that local governments’ goal in accounting for public preferences locally is to follow the mayor’s personal ideology as well as democratic values while predominantly improving their political gains.

Using a mixed-method design, this study presents three religion-based policies in Israel, namely: marriage, public transportation and commerce on the Jewish Saturday (Sabbath) – each restricts public services. It then paints on the mechanism behind efforts made by local governments to supply the lacking public services resulting from these policies as an act of local responsiveness with the purpose of being re-elected.

Literature review

Institutional constraints leading to fixated religious state policies

Institutions are professed as top-down oriented entities, humanly devised rules, procedures and standard operating practices – both formal and informal rules and norms (North Citation1990) that constrain and enable political behaviour within the state and society (North Citation1990; Steinmo Citation2014). Indeed, politics and political actors are shaped by institutional constraints, defining and potentially limiting their ability to affect policies (Tsebelis Citation1990).

Within the institutional framework, religion is considered a classic example of institutional constraints, as it frequently takes on an institutional form (Gill Citation2001) that structures its position in the governmental arena (Casanova Citation1994). In democratic states that do not separate religion and politics, religious rules may be incorporated into official policies (Gill Citation2001), directly influencing the provision of public services.

When a religious monopoly is evident, the likelihood of dissatisfaction with policy increases as people’s varying needs cannot be satisfied by a single provider (Pollack and Olson Citation2012). Iannaccone (Citation1991) and Gill (Citation2021) argue that pluralistic religious environments are more vibrant and participatory than state-supported monopolistic-religious ones and provide members with goods and services that they value, solving societal dissatisfaction. Such theories assume that people approach religion as they approach any other choice. They may change their preferences or levels of religious participation over time (Iannaccone Citation1998). Hence, it may create a misalignment between citizens’ preferences and existing state policies, and in turn, the services they allow or/and forbid.

Citizen’s wish for lacking public services – Gap between citizens’ preferences and existing public policies

The link between citizen’s preferences and existing public policies is positioned at the heart of democratic theory (Dahl Citation1971; Soroka and Lim Citation2003). In democracies, public opinion influences public policy (Dahl Citation1971), whereas the link between the two is even stronger in cases where the issue-in-point is of greater importance to the public.

Evidently, the duties of governments in designing policies and the demands of democratic representation may, at times, be in contrast with one another (Karremans and Lefkofridi Citation2020). Equivalence between what citizens want and what their governments do, is crucial for the functioning of representative democracy (Dahl Citation1971; Golan-Nadir Citation2022; Powell Citation2006). Consequently, the lack of responsiveness constitutes a democratic deficit (Golan-Nadir Citation2022; Warren Citation2013). Such deficits are expected when institutional barriers prevent government responsiveness to the public’s will (Guntermann and Persson Citation2023).

Despite the notion that most citizens have limited knowledge of politics, often they are capable of thinking critically about policy alternatives that they deem preferable (Burstein Citation2010; Dahl Citation1971). According to Burstein (Citation2010), the impact of citizens’ preferences on public policy is amazingly robust. It is further argued that as the government complies with the public’s demands to make changes, in return, in order to express satisfaction, the public adjusts its preferences accordingly and ceases to pressure change (Burstein Citation2010; Soroka and Lim Citation2003; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2005; Wlezien Citation1995, Citation2004). Nonetheless, citizen’s high democratic expectations lead to political disengagement and institutional distrust as they recognise the wide gap between politicians, government, and citizens (Dalton Citation2004; Norris Citation1999).

Perhaps, the most obvious signal that focuses attention on inefficiency is the consumer complaint, which is used as an indicator of public discontent. These complaints express public opinion by ‘voice’, as professed by Albert Hirschman (Citation1970, Citation1993). In his exit, voice and loyalty model, Hirschman explains that when consumers are dissatisfied with a certain product, they may choose either the voice option, meaning they will demand better outcomes, or use the ‘exit’ option and leave the firm offering the product.

Consequently, as long as the citizen’s preferences are not reflected in the political decision-making process, the gap between these preferences and existing policies remains as it stands. Here, local governments can provide remedies to disparities between civil will and public services dictated by existing policies (de Sousa, da Cruz, and Fernandes Citation2023; Gundelach, Buser, and Kübler Citation2017; Michels and De Graaf Citation2010). In fact, local governments can make the Hirschmanian ‘exit’ option available.

Local governments and public service delivery

Politicians may be referred to as agents of interests and preferences with the objective of making institutional changes (March and Olsen Citation1998), namely elites who might try and undermine institutional constraints in different ways (Burstein Citation2003). In the local context, local governments are considered important actors in providing public services (Benito et al. Citation2019; Di Porto and Paty Citation2018; Dollery, Marshall, and Sorensen Citation2007). Within Western democracies, there is an increased need to evaluate local public service provision and ongoing attempts to reform, while increasing the quality of services, and thus the satisfaction of citizens with the latter (Koprić, Wollmann, and Marcou Citation2018). This reinforces overall accountability (Dollery, Marshall, and Sorensen Citation2007; Kluvers Citation2003; Kluvers and Tippett Citation2010), and enhances the responsiveness of municipal governments (Tausanovitch and Warshaw Citation2014).

Additionally, public services provided by local governments are not only assessed in terms of the service quality but also according to how they fit the interest and the welfare of the community as well as the values of democracy (Dollery, Marshall, and Sorensen Citation2007). In turn, the performance of local services is a predictor of trust in the local government (Naraidoo and Sobhee Citation2021). Nonetheless, potential benefits that the provision of services by the local government provides could be limited due to national legislation, namely constraints (Ehtisham, Brosio, and Tanzi Citation2008; Golan-Nadir and Christensen Citation2023). To overcome such restrictions, local governments might take creative initiatives that in turn can lead to increased electoral support, making service delivery at the local level a key factor for re-election (Sundell and Lapuente Citation2011).

Local service delivery motivated by re-election

Politicians are said to have various motivations for holding office. They range from satisfaction from power (e.g., perks of the job), civic duty, idealism to make their community a better place or concerning policy outcomes (Ashton, Kushner, and Siegel Citation2008; Callander Citation2008; Van der Wal Citation2013), as well as financial reward (Finan and Ferraz Citation2009).

Nonetheless, producing reforms to change or initiate a lack of public services may not be motivated by the mere concern of policy outcomes (Callander Citation2008), as democratic governments seek to enhance their chances of re-election by managing the portfolio of policy (Ben-Porat Citation2006; Bertelli and John Citation2013; Golan-Nadir and Cohen Citation2017; Vogel Citation1996). For politicians in office, reforming public sector institutions is a crucial investment for re-election (Hagen Citation2002). It is further argued that even long-standing politicians try and produce change in order to be re-elected, as during the next campaign, they will have to explain the changes they have achieved (Ashton, Kushner, and Siegel Citation2008; Balaguer-Coll et al. Citation2015; Hagen Citation2002). Indeed, once elected, many seek re-election and often turn the mayoral position, if successful, into a lifetime career (Wollmann Citation2008). Thus, local politicians are constantly aware of the public’s tendencies. For example, when local politicians award contracts, they do not only consider the price but also the environmental, social, and innovative criteria, regardless of their political ideology (Lerusse and Van de Walle Citation2021), which can also be attributed to the longing for political gain.

From the electorate’s viewpoint, policy reforms may affect voting behaviour by signalling the commitment of the incumbent to fulfil the mandate for change that reflects renewed political priorities among the electorate (Buti et al. Citation2010). Further, the direct election of mayors has contributed to enhancing the quality of local service and the responsiveness of local action, because the mayors are interested in their re-election and thus, seek to behave in both a more customer-oriented and citizen-friendly manner (Kuhlmann Citation2009). (below) illustrates the hypotheses of the study.

The context –Religious policies in Israel

In the Israeli context, the dynamic between religion and state politics is rooted at the critical juncture of the state establishment. Israel was established in 1948 and is defined as a ‘Jewish and democratic state’. This unique official character creates a fundamental difficulty in separating state and religion (Barak-Erez Citation2009; Golan-Nadir Citation2022; Rubin Citation2020).

With the advance of statehood, founding father David Ben-Gurion stated that no body in the country is authorised to determine in advance the constitution of the Jewish state, and its secular character. Consequently, the position of Judaism in the state was defined by a series of political arrangements (Horowitz and Lissak Citation1989, 228), according to which religion is officially incorporated into four realms of policy (i.e., ‘the status-quo’). The status-quo is the basic formula for conflict resolution in matters of religion and state in Israel (Sapir Citation1998), stipulating policy principles in four fundamental areas to Orthodox Judaism: Shabbat (keeping the Jewish Saturday including a ban of public transport and commerce); Kashrut (keeping Jewish kosher laws of food in public state institutions); Family law (Orthodox marriage and divorce); and Education (two secular/religious routes) (see in Golan-Nadir Citation2022). It also influences realms outside of the status-quo as: conscription, autopsy, burial and conversion to Judaism.

Among Israeli-Jews, there is a broad consensus that Israel should be a ‘Jewish state’, yet deep controversies exist over its conduct of everyday life (Ben-Porat Citation2008). Such controversies are visible at the local government level, as the latter supply several religiously restricted services. Evidently, in an ongoing process, local governments provided solutions to the lacking services in a lawful way to account for the needs of their secular residents. In realms such as public transportation and commerce on Shabbat and local marriage registry, solutions that do not break the law, yet push back from national government, were established. Nonetheless, for realms such as Kashrut and mandatory official education that are solely at the central government’s authority, no legal way to detour from it is evident.

Other policies are also affected by the status-quo yet are challenging to account for locally. For example, autopsy, conversion to Judaism and conscription are impossible to account for locally as they are highly connected to the entire Jewish collective and, hence, extremely centralised. Lately, developments in secular burial are in progress yet depend on the state for allocating land, hence less indicative.

Research design

To test our hypotheses, we have used a mixed-method single-case study design (Franklin, Allison, and Gorman Citation2014). Specifically, this study researches Israeli-Jews in cities with Jewish majority in Israel. The best form to describe this mixed-method research is the ‘Convergent Design’, where both quantitative and qualitative data are collected and analysed during the same phase of the research process, to obtain different, but complementary data (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2017). In using the Israeli case, we aim to establish that religion, as a realm of policy in a democratic state, may be considered paradigmatic – a public policy that allows or restricts public services – just as any other realm of policy.

Data collection and analysis include multiple tools to measure our variables:

In order to test condition (1) as part of the independent variable, ‘a lacuna in public services at the national level due to institutional constraints’, we have used a qualitative tool:

Textual analysis of primary and secondary sources

The primary source material includes official legislation from Israeli state institutions (i.e., the Knesset, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Religious Services, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel). We also used secondary source materials such as reports issued by research centres and newspaper articles. This tool also measures the dependent variable, ‘local governments to account for public preferences’, as it portrays the local governments that supply the lacking public services via their official websites, newspaper and social media publications, as well as the ‘2023 Municipal Freedom Index’Footnote1 initiated by the Free Israel association, which lists local governments by their degree of freedom from religion.

In order to test condition (2) as part of the independent variable, ‘societal dissatisfaction as expressed by public opinion’, we have used two quantitative data collection tools that compliment each other by allowing to set a trend in public attitudes along the decades and conclude with a snap-shot of the phenomenon in 2023:

Existing statistics. Existing statistics (i.e., state official statistics, public opinion surveys conducted by research centres) provide a clear and supposedly accurate picture of the phenomenon.

Public Opinion Surveys. We have conducted four online surveys to learn on citizen’s trust in their local governments vs. the central government. This is in order to realise which they trust more to meet their demands. The surveys were initiated by the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University. All surveys were fielded to a representative sample of Israeli-Jews: survey 1 – September 22 and October 2, 2022, N = 1,416; survey 2 – October 24–27, 2022, N = 1,206; survey 3 – March 19–22, 2023, N = 1,257; survey 4 – September 3–6, 2023, N = 1,227.

In order to test condition (3) as part of the independent variable, ‘local politicians in search for re-election’, we have used a qualitative tool:

In-depth interviews

To obtain a more detailed understanding of the creation process of lacking services, we conducted 20 in-depth interviews between May and October 2023. The interviewees were sampled through ‘snowball sampling’ (Robinson Citation2014) and targeted several samples of participants that shed light on the described phenomenon from different perspectives; (a) local government officials (b) founders of third-sector organizations and (c) professional experts – academicians specializing in local government (interviews non-anonymised to participant’s request).

The municipalities whose officials were selected to be interviewed were chosen out of the Free Israel ‘2023 Municipal Freedom Index’. Only cities that scored high on the index were chosen, namely those supplying lacking public services due to religious constraints. Overall, the interviewees were asked to paint on the local service production of lacking services, its legality and ability to sustain. Those involved in the process were asked to describe their goals in taking part in the creation of services at the local level.

Findings

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics official data, 74% of Israelis are affiliated as Jews (CBS Selected Annual Data Citation2021a), of whom 44.8% are non-religious-secular, 33% are traditional,Footnote2 11.7% are religious and 10% are ultra-Orthodox (CBS Report on Level of Religiousness Citation2021b). These demographics have a strong impact on the national-level parliamentary system, as the three major religious political parties (i.e., The Jewish Home, Shas, and United Torah Judaism) receive on average about 20% of the combined current vote in Israel (an increase from 15% since mid-90s). The religious parties are historically represented in the Israeli parliament (Knesset), and mostly provide a balancing scale to the right-wing parties in coalition building (Freedman Citation2020). At the subnational level, it is the cities’ local demography that determines the delegates to the city council. The local societal texture is fairly constant or changes moderately due to local migration. Hence, responding to their population, local governments decide whether to supply public services that are lacking due to religious constraints.

Lacuna in central government’s service provision due to institutional constraints

Israel is highly centralised vis-à-vis the central government. Centralisation is expressed via the lack of independence and over-regulation of local authorities. In an index of decentralisation of power to local authorities, Israel is last among OECD countries (Finkelstein Citation2021). Overall, the central and local parliamentary systems in Israel are separated, yet some local politicians are associated with national-level political parties. The latter are interested in their election to enhance its ideological grip in municipalities.

All across the board, our participants agree that it is the religion-based institutional constraints that lead to the lacuna in public services (Interviewee 1–20). As some mayors and council members have stated, Israel is systematically taking a stand that pays less attention to people’s needs (Interviewee 1, 16–20). Evidently, the government enacts a single law for the entire citizenry – assuming it is suitable for all (Interviewee 3). However, the needs of the secular population are different (Interviewee 1–3, 8, 12–13, 15–16), making state and religion issues the core of the debate within Israeli society (Interviewee 4).

paints on the three main public services supplied by local governments due to their lack at the national level, namely: local marriage registry for all types of couples, public transportation and commerce on the Shabbat.

Table 1. Religious bans by central government vs. service initiation by local governments.

These services are supplied by local governments due to societal need for the services, in an act of Hirschmanian ‘exit’.

Societal dissatisfaction as expressed by public opinion

Following the democratic need for an overlap between policies and its consequent services and public preferences (Dahl Citation1971), the public should be detected. Practically, various surveys collected by the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research at the Israel Democracy Institute show that Israeli-Jews are long dissatisfied with several public services that are lacking due to religious constraints.

The three realms described below are most noted and accounted for locally:

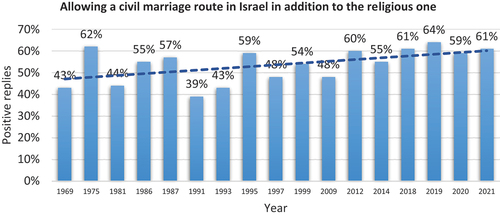

Marriage

As illustrated in , when asking on support in allowing a civil marriage route in Israel in addition to the religious one, the surveys’ accumulative positive replies have shown substantial support.

Additionally, 64% (2018) support allowing same-sex marriage, and 54% (2015), 65% (2018) and 59% (2021) support granting same-sex couples equal rights. Moreover, in a 2022 survey by the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University, 65% said they completely agreed or mostly agreed with allowing a civil marriage route in Israel in addition to the religious one.

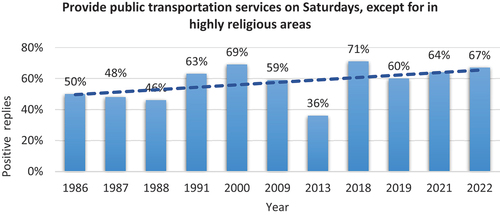

Public transportation

As illustrated in , when asking on support in allowing public transportation services on Saturdays, except for in highly religious areas, the surveys’ accumulative positive replies have shown substantial support.

Further, in a 2022 survey by the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University, 63% said they completely or mostly agreed that Israel needs to provide public transportation services on Saturdays, except for in highly religious areas.

Commerce on Saturday (Shabbat)

Societal zeitgeist regarding various aspects within the realm of commerce on Saturday was studied. Surveys show that 63% (1999) and 58% (2009) support the operating of shopping centres on Saturdays. Additionally, 68% (2018) and 60% (2019) support the operation of supermarkets on Saturday. Finally, 75% (1999), 67% (2009), and 72% (2018) support the operation of restaurants and cafés on Saturday.

Local governments supply of lacking services

Aware of the public zeitgeist on issues of religion and state, local governments have gradually begun initiating the public services their residents long for. Surveys conducted for this research purpose by the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University, indicate that Israeli-Jews have more trust in the local government over the central one. As shows, though low all-together, throughout all four surveys the results were kept roughly steady.

Table 2. Level of trust in local government vs. Central government.

The reason for such gap in levels of trust may be attributed to the local supply of nationally lacking services. Our participants admitted that local governments constantly examine their resident’s needs, so they can come up with relevant solutions (Interviewee 1–3, 5–7, 9, 12–13, 15–16). As Yuval Bartov, a local government expert argues, ‘the fact that local governments have begun providing additional services to the state, and sometimes contrary to its policies, proves that local governments work to satisfy the will of their population’ (interviewee 19). This is further reinforced by Itai Beeri, Professor of Local Government, who claims that local government officials tend to identify needs and provide remedies, as they are managers that supply services (interviewee 18).

Several local government officials explained that, without the involvement of the state, has failed the people, we must deliver services ourselves. Citizens expect this of us (Interviewee 1, 13, 15). A deputy Mayor highlighted that, ‘municipalities “put a little finger in the government’s eye”, while rewarding their residents with public services that are lacking nationally’ (Interviewee 5), so that they can enable their residents to live according to their preferences (Interviewee 1–3, 8, 12–13, 15–16). Interestingly, one mayor stated that he supplies these services despite that it does not correspond with his personal beliefs. He said, ‘I pray and go to the synagogue on Shabbat, but when I see that there is a demand by the young residents to have access to transportation, it touches me’ (Interviewee 12).

Additionally, mayors and their counterparts are also aware that they can only supply the lacking services if it does not surpass more conservative resident’s rights. A legal expert said, ‘it is important that the city adapts itself to the beliefs of its residents. Each and every city should create its own status-quo regarding these issues’ (Interviewee 14). Several other participants have highlighted this notion, arguing that they will do anything in their power to please their residents, as long as they do not harm other communities (Interviewee 1–3, 10, 12). Thus, in the future, said a Deputy Mayor, ‘each of us, whether religious or secular, will decide which city they want to live in; a secular and free city, a religious city or a mixed city’ (Interviewee 15).

Local politicians – Ideology and political gains

Local politicians hold incentives while providing lacking public services. Our interviewees have highlighted that their main incentive is getting re-elected, combined with personal ideology and democratic values (Interviewee 3, 8–11, 18–19). Maoz Rosenthal, a professor specialising in elections, argued that in their political quest, mayors hold some kind of ideology, but the desire to be re-elected is their grave engine (interviewee 20). Our interviewees claimed that, “getting re-elected means meeting the public’s demands, hence corresponds with the democratic game legitimately (Interviewee 4, 13, 15–16), and ‘this is a win-win for everyone’ (Interviewee 5–6). More specifically, one mayor said, “at the end of the day, the public comes and says, ‘I chose you. I want you to solve my problems’ (Interviewee 3). Social activists added that sometimes ideology can play a role, but most of the time it is the longing to influence the electorate (Interviewee 8, 10–11). As one deputy mayor said, ‘This is our job to do what is best for our residents. In return, we want them to support us with their votes, so that we are able to continue and deliver for them’ (Interviewee 13). Hence, the mayor’s ideology and longing for re-election go hand in hand (interviewee 18–19).

Discussion

The local provision of lacking public services is obeying to the democratic principle of an overlap between policies, and its consequent services, and public preferences (Dahl Citation1971; Golan-Nadir Citation2022; Soroka and Lim Citation2003). Democracies make an effort to account for the public will, but in more fragmented societies they are faced with conflicting demands. Indeed, in fragmented societies (Harell and Stolle Citation2010) public preferences vary with the different categories of societal diversity (among Israeli-Jews, fragmentation is based on level of religiosity). Hence, as local governments contain more homogeneous populations, they are able to account for public preferences more efficiently, facing less societal friction.

A successful case of local provision of nationally lacking service might call for a move towards delegating power to local governments in democratic regimes where the central government institutionalises more centralised delegation of powers between the central and the local polities. Especially in fragmented societies, a more local account for public preferences might increase the overall trust citizens have (both in local and in central governments) as well as their level of satisfaction with public services. It might also reduce societal tensions between different populations (Golan-Nadir and Christensen Citation2023).

Nevertheless, such a phenomenon may also be considered a threat to the democratic system’s stability when conducted at the local level. The provision of intensive, large-scale services at the local level may increase the inequality between wealthy and poor local authorities, and prevent the allocation of local budgets for other mandatory essential local services such as: healthcare, education and culture. It might also increase the popularity of local politicians who provide the lacking public services to gain popularity and enhance their electoral support and do not mind other local communities that might be offended by the services, if not supplied in an adjusted way. Consequently, whether local provision of lacking public services should be exercised, should be considered on a case-specific basis, as each democracy differs in its institutional arrangements, culture, and societal cleavages (Lijphart Citation1994).

Conclusion

This study investigated under which circumstances local governments’ responsiveness to its residents’ preferences overtakes the central government’s accountability for public preferences in democracies. It hypothesised that, (1) A lacuna in public services at the national level due to institutional constraints, leading to (2) societal dissatisfaction as expressed by public opinion, as well as (3) local politicians in search for re-election, will lead local governments to account for public preferences. We have further argued that local governments’ goal in accounting for public preferences locally is to follow the mayor’s personal ideology as well as democratic values while predominantly improving their political gains. Our hypotheses were supported by the study’s data.

Transferability-wise, the hypotheses tested here can be verified in other democratic states that contain institutional-based policy restrictions (e.g., education, taxes and social work) for which local governments account. Hence, although other or additional elements may encourage local government’s service supply in other contexts, the mechanism presented here can be considered a preliminary framework for future research. This is to say that our overall theoretical hypotheses are generalised, while the case in point may be considered as a paradigmatic one, leaving future researchers with only minor adjustments if borrowing from this study to different realms of policy.

Future studies in this realm should try and explore long-term satisfaction with the local provision of lacking services, namely to what extent are citizens content with the local supply of lacking services? Would they rather the state provides it still? Why? It should also address the economic-procedural effectiveness of local provision of newly introduced public services, especially in the realm of services like public transport that are more efficiently reticulated state-wide. Further, concerns that should be studied relate to cities that are divided in their longing for lacking services. Such division might cause local societal unrest. Moreover, the financial aspects of local service provision should be studied. Indeed, taking away from the city’s budget might endanger other services such as: education, culture, sanitation and more. Hence, future studies might recommend new strategies for local governments to manage the extra burden the supply of such services imposes.

List of interviews

Interviewee 1 – Mayor of a city in central Israel, 22 May 2023

Interviewee 2 – Mayor of a city in central Israel, 20 June 2023

Interviewee 3 – Mayor of a city in central Israel, 5 June 2023

Interviewee 4 – CEO of an NGO for religious freedom, 21 May 2023

Interviewee 5 – Deputy Mayor of a city in central Israel, 27 June 2023

Interviewee 6 – Former Deputy Mayor of a city in central Israel, 3 August 2023

Interviewee 7 – Deputy Mayor of a city in central Israel, 30 July 2023

Interviewee 8 – Social activist and co-founder of NGO for equality, 16 July 2023

Interviewee 9 – Municipality Council Member of a city in central Israel, 24 July 2023

Interviewee 10 – Founder and CEO of an NGO for justice and equality, 7 August 2023

Interviewee 11 – Founder and CEO of an NGO for social initiatives, 8 August 2023

Interviewee 12 – Mayor of a city in central Israel, 18 July 2023

Interviewee 13 – Deputy Mayor of a city in central Israel, 8 August 2023

Interviewee 14 – Attorney at law and social activist in an NGO for equality, 2 August 2023

Interviewee 15 – Deputy Mayor of a city in central Israel, 17 August 2023

Interviewee 16 – City Council Member of a city in central Israel, 16 August 2023

Interviewee 17 – Director at a centre of Jewish thought and education, 21 August 2023

Interviewee 18 – Itai Beeri, academician, University of Haifa, 22 October 2023

Interviewee 19 – Yuval Bartov, the Local Government Project, The Israel Democracy Institute, 24 October 2023

Interviewee 20 – Maoz Rosenthal, academician, Hadassah Academic College, 26 October 2023

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Niva Golan-Nadir

Dr. Niva Golan-Nadir is a research associate at the Center for Policy Research, Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy at The University at Albany, SUNY, and a research fellow at the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility, Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy at Reichman University. Her research interests include: Comparative Politics, Religion and State and Public Administration. Her recent book, Public Preferences and Institutional Designs: Israel and Turkey Compared (2022), has been awarded ‘final list and honorary mention’ by the Azrieli Institute of Israel Studies and Concordia University Library.

Jessica Blumberg

Jessica Blumberg is an undergraduate student at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy at Reichman University. She specializes in Business Administration, Global Affairs and Emerging Technologies. She has contributed to this article while participating in the school’s Research Cadets program.

Hadar Ester Baranes

Hadar Ester Baranes is a graduate student at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy at Reichman University. She specializes in Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution. She has contributed to this article while participating in the school’s Research Cadets program.

Notes

1. See index in: https://madad.israelhofsheet.org.il/english-about.

2. Traditional Jews do not necessarily avoid travelling on the Sabbath, marry religiously or eat Kosher food. It is a very individual-fluid definition.

References

- Abdullah, H. S., and M. Kalianan. 2008. “The Customer Satisfaction to Citizen Satisfaction: Rethinking Local Government Service Delivery in Malaysia.” Asian Social Science 4 (11): 87–92. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5365/64386ee446542d6f76a2058f4d5610282dc5.pdf.

- Afonso, A., and S. Fernandes. 2008. “Assessing and Explaining the Relative Efficiency of Local Government.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 37 (5): 1946–1979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2007.03.007.

- Ashton, M., J. Kushner, and D. Siegel. 2008. “Personality Traits of Municipal Politicians and Staff.”Canadian Public Administration.” Canadian Public Administration 50 (2): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2007.tb02013.x.

- Balaguer-Coll, M. T., M. I. Brun-Martos, A. Forte, and E. Tortosa-Ausina. 2015. “Local Governments’ Re-Election and Its Determinants: New Evidence Based on a Bayesian Approach.” European Journal of Political Economy 39:94–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.04.004.

- Barak-Erez, D. 2009. “Law and Religion Under the Status-Quo Model: Between Past Compromises and Constant Change.” Cardozo Law Review 30 (6): 2495–2507. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1596748.

- Ben-Bassat, A., M. Dahan, and E. F. Klor. 2016. “Is Centralization a Solution to the Soft Budget Constraint Problem?” European Journal of Political Economy 45 (1): 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.09.005.

- Benito, B., Ú. Faura, M. D. Guillamón, and A. M. Ríos. 2019. “The Efficiency of Public Services in Small Municipalities: The Case of Drinking Water Supply.” Cities 93:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.016.

- Ben-Porat, G. 2006. Global Liberalism, Local Populism: Peace and Conflict in Israel/Palestine and Northern Ireland. New-York: Syracuse University Press.

- Ben-Porat, G. 2008. Israel Since 1980. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511756153.

- Bertelli, A. M., and P. John. 2013. “Public Policy Investment: Risk and Return in British Politics.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (4): 741–773. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000567.

- Burstein, P. 2003. “The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda.” Political Research Quarterly 56 (1): 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600103.

- Burstein, P. 2010. “Public Opinion, Public Policy, and Democracy.” In Handbook of Politics, edited by K. T. Leicht and J. C. Jenkins. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research 63–79. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-68930-2_4.

- Buti, M., A. Turrini, P. Van den Noord, P. Biroli, M. Thoenig, and E. Zhuravskaya. 2010. “Reforms and Re-Elections in OECD Countries.” Economic Policy 25 (61): 61–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2009.00237.x.

- Callander, S. 2008. “Political Motivations.” The Review of Economic Studies 75 (3): 671–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00488.x.

- Casanova, J. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- CBS. 2021a. Report on Israel in Figures—Rosh Hashana Selected Annual Data 2021. Report Number 301. Jerusalem, Israel: Central Bureau of Statistics. September 5, 2021.

- CBS. 2021b. Report on Religion and Self-Definition of Level of Religiosity 2020. Report Number 28.6. Jerusalem, Israel: Central Bureau of Statistics. August 31, 2021.

- Creswell, J. W., and V. L. Plano Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. New York: Sage publications.

- Dahl, R. A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, R. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in the Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001.

- de Sousa, L., N. F. da Cruz, and D. Fernandes. 2023. “The Quality of Local Democracy: An Institutional Analysis.” Local Government Studies 49 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1882428.

- Di Porto, E., and S. Paty. 2018. “Cooperation Among Local Governments to Deliver Public Services.” Politics & Policy 46 (5): 790–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12275.

- Dollery, B., N. Marshall, and T. Sorensen. 2007. “Doing the Right Thing: An Evaluation of New Models of Local Government Service Provision in Regional New South Wales.” Rural Society 17 (1): 66–80. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.351.17.1.66.

- Dzigbede, K. D., S. B. Gehl, and K. Willoughby. 2020. “Disaster Resiliency of US Local Governments: Insights to Strengthen Local Response and Recovery from the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Public Administration Review 80 (4): 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13249.

- Ehtisham, A., G. Brosio, and V. Tanzi. 2008. “Local Service Provision in Selected OECD Countries: Do Decentralized Operations Work Better?” IMF Working Paper 08/67. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp0867.pdf.

- Finan, F., and C. Ferraz. 2009. “Motivating Politicians: The Impacts of Monetary Incentives on Quality and Performance.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 14906. https://eml.berkeley.edu/~ffinan/Finan_MPoliticians.pdf.

- Finkelstein, A. 2021. The State of Israel Is Stuck in the 1980s. Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute. https://en.idi.org.il/articles/33491.

- Fox, J., and S. Sandler. 2005. “Separation of Religion and State in the Twenty-First Century: Comparing the Middle East and Western Democracies.” Comparative Politics 37 (3): 317–335. https://doi.org/10.2307/20072892.

- Franklin, R. D., D. B. Allison, and B. S. Gorman, Eds. 2014. Design and Analysis of Single-Case Research. New York: Psychology Press.

- Freedman, M. 2020. “Vote with Your Rabbi: The Electoral Effects of Religious Institutions in Israel.” Electoral Studies 68:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102241.

- García‐Sánchez, I. M. 2006. “Efficiency Measurement in Spanish Local Government: The Case of Municipal Water Services.” The Review of Policy Research 23 (2): 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2006.00205.x.

- Gill, A. 2001. “Religion and Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 4 (1): 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.117.

- Gill, A. 2021. “The Comparative Endurance and Efficiency of Religion: A Public Choice Perspective.” Public Choice 189 (3): 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00842-1.

- Golan-Nadir, N. 2022. Public Preferences and Institutional Designs: Israel and Turkey Compared. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Golan-Nadir, N., and T. Christensen. 2023. “Collective Action and Co-Production of Public Services as Alternative Politics: The Case of Public Transportation in Israel.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 82 (1): 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12578.

- Golan-Nadir, N., and N. Cohen. 2017. “The Role of Individual Agents in Promoting Peace Processes: Business People and Policy Entrepreneurship in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict.” Policy Studies 38 (1): 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2016.1161181.

- Gundelach, B., P. Buser, and D. Kübler. 2017. “Deliberative Democracy in Local Governance: The Impact of Institutional Design on Legitimacy.” Local Government Studies 43 (2): 218–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1261699.

- Guntermann, E., and M. Persson. 2023. “Issue Voting and Government Responsiveness to Policy Preferences.” Political Behavior 45 (2): 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09716-8.

- Hagen, R. J. 2002. “The Electoral Politics of Public Sector Institutional Reform.” European Journal of Political Economy 18 (3): 449–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(02)00100-3.

- Harell, A., and D. Stolle. 2010. ““Diversity and Democratic Politics: An Introduction.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 43 (2): 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000842391000003X.

- Henderson, I. 1986. “Local Government’s Role in Emergency Planning: Sheep Scab, Warble Fly, and the End of the World As We Know it.” Local Government Studies 12 (4): 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003938608433279.

- Hirschman, A. O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hirschman, A. O. 1993. “Exit, Voice, and the Fate of the German Democratic Republic: An Essay in Conceptual History.” World Politics 45 (2): 173–202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950657.

- Ho, A. T. K. 2002. “Reinventing Local Governments and the E‐Government Initiative.” Public Administration Review 62 (4): 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00197.

- Horowitz, D., and M. Lissak. 1989. Trouble in Utopia: The Overburdened Polity of Israel. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Iannaccone, L. R. 1991. “The Consequences of Religious Market Structure: Adam Smith and the Economics of Religion.” Rationality and Society 3 (2): 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463191003002002.

- Iannaccone, L. R. 1998. “Introduction to the Economics of Religion.” Journal of Economic Literature 36 (3): 1465–1495. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2564806.

- Karremans, J., and Z. Lefkofridi. 2020. “Responsive versus Responsible? Party Democracy in Times of Crisis.” Party Politics 26 (3): 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761199.

- Klocek, J., and D. P. Petri. 2023. “Measuring Subnational Variation in Freedom of Religion or Belief Violations: Reflections on a Path Forward.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 21 (2): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2023.2200278.

- Kluvers, R. 2003. “Accountability for Performance in Local Government.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 62 (1): 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00314.

- Kluvers, R., and J. Tippett. 2010. “Mechanisms of Accountability in Local Government: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Business & Management 5 (7): 46–53. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v5n7p46.

- Koprić, I., H. Wollmann, and G. Marcou, eds. 2018. Evaluating Reforms of Local Public and Social Services in Europe: More Evidence for Better Results. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61091-7.

- Kuhlmann, S. 2009. “Reforming Local Government in Germany: Institutional Changes and Performance Impacts.” German Politics 18 (2): 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644000902870842.

- Kuru, A. T. 2007. “Passive and Assertive Secularism: Historical Conditions, Ideological Struggles, and State Policies Toward Religion.” World Politics 59 (4): 568–594. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2008.0005.

- Lerusse, A., and S. Van de Walle. 2021. “Local Politicians’ Preferences in Public Procurement: Ideological or Strategic Reasoning?” Local Government Studies 48 (4): 680–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1864332.

- Lijphart, A. 1994. “Democracies: Forms, Performance, and Constitutional Engineering.” European Journal of Political Research 25 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1994.tb01198.x.

- Lowndes, V., and K. McCaughie. 2013. “Weathering the Perfect Storm? Austerity and Institutional Resilience in Local Government.” Policy & Politics 41 (4): 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655747.

- March, J. G., and J. P. Olsen. 1998. “The Institutional Dynamics of International Political Orders.” International Organization 52 (4): 943–969. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550699.

- Michels, A., and L. De Graaf. 2010. “Examining Citizen Participation: Local Participatory Policy Making and Democracy.” Local Government Studies 36 (4): 477–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2010.494101.

- Naraidoo, S., and S. K. Sobhee. 2021. “Citizens’ Perceptions of Local Government Services and Their Trust in Local Authorities: Implications for Local Government in Mauritius.” Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research 15 (3): 353–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/09738010211010515.

- Nicholson, W. C. 2007. “Emergency Planning and Potential Liabilities for State and Local Governments.” State & Local Government Review 39 (1): 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X0703900105.

- Norris, P., ed. 1999. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198295685.001.0001.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808678.

- Perry, R. W., and M. K. Lindell. 2003. “Preparedness for Emergency Response: Guidelines for the Emergency Planning Process.” Disasters 27 (4): 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2003.00237.x.

- Pollack, D., and D. V. A. Olson. 2012. The Role of Religion in Modern Societies. London: Routledge.

- Powell, G. B. 2006. “Election Laws and Representative Governments: Beyond Votes and Seats.” British Journal of Political Science 36 (2): 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123406000160.

- Pradana, M., N. Rubiyanti, I. Hasbi, and D. G. Utami. 2020. “Indonesia’s Fight Against COVID-19: The Roles of Local Government Units and Community Organisations.” Local Environment 25 (9): 741–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2020.1811960.

- Razin, E., and A. Hazan. 2014. “Attitudes of European Local Councillors Towards Local Governance Reforms: A North–South Divide?” Local Government Studies 40 (2): 264–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.747957.

- Robinson, O. C. 2014. “Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 11 (1): 25–41.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543.

- Rubin, A. 2020. Bounded Integration: The Religion-State Relationship and Democratic Performance in Turkey and Israel. New York: SUNY Press.

- Sapir, G. 1998. ““Religion and State in Israel: The Case for Reevaluation and Constitutional Entrenchment.” Hastings International & Company Law Review 22:617–666.

- Sciulli, N. 2018. “Weathering the Storm: Accountability Implications for Flood Relief and Recovery from a Local Government Perspective.” Financial Accountability & Management 34 (1): 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12134.

- Shaykhutdinov, R. 2013. “Accommodation of Islamic Religious Practices and Democracy in the Post-Communist Muslim Republics.” Politics and Religion 6 (3): 646–670. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048312000764.

- Shaykhutdinov, R. 2024. “Religion and Subnational Public Policy: Accommodation of Minority Religious Practices in the Post-Communist Muslim Republics.” In Handbook on Subnational Governments and Governance, edited by C. N. Avellaneda and R. A. Bello-Gómez, 232–248. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Soroka, S. N., and E. T. Lim. 2003. “Issue Definition and the Opinion-Policy Link: Public Preferences and Health Care Spending in the US and UK.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 5 (4): 576–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.00120.

- Soroka, S. N., and C. Wlezien. 2005. ““Opinion–Policy Dynamics: Public Preferences and Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Political Science 35 (4): 665–689. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123405000347.

- Steiner, R., C. Kaiser, C. Tapscott, and C. Navarro. 2018. “Is Local Always Better? Strengths and Limitations of Local Governance for Service Delivery.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 31 (4): 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-05-2018-226.

- Steinmo, S. 2014. “Historical Institutionalism and Experimental Methods.” Paper presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2455247.

- Stepan, A. C. 2000. “Religion, Democracy, and the “Twin Tolerations”.” Journal of Democracy 11 (4): 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2000.0088.

- Sundell, A., and V. Lapuente. 2011. “Adam Smith or Machiavelli? Political Incentives for Contracting Out Local Public Services.” Public Choice 153 (3–4): 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9803-1.

- Tausanovitch, C., and C. Warshaw. 2014. “Representation in Municipal Government.” American Political Science Review 108 (3): 605–641. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000318.

- Tsebelis, G. 1990. California Series on Social Choice and Political Economy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Uster, A., and N. Cohen. 2023. ““Local Government’s Response to Dissatisfaction with Centralized Policies: The “Do-It-Yourself” Approach.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 89 (3): 825–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523221094414.

- Van der Wal, Z. 2013. “Mandarins versus Machiavellians? On Differences Between Work Motivations of Administrative and Political Elites.” Public Administration Review 73 (5): 749–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12089.

- Vogel, D. 1996. Kindred Strangers: The Uneasy Relationship Between Politics and Business in America. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv5cg9gq.

- Warren, M. E. 2013. “Citizen Representatives.” In Representation: Elections and Beyond, edited by J. H. Nagel and R. M. Smith, 269–294. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812208177.269.

- Wayenberg, E., S. L. Resodihardjo, J. Voets, M. Van Genugten, B. Van Haelter, and I. Torfs. 2022. “The Belgian and Dutch Response to COVID-19: Change and Stability in the Mayors’ Position.” Local Government Studies 48 (2): 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1958787.

- Wlezien, C. 1995. “The Public As Thermostat: Dynamics of Preference for Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666.

- Wlezien, C. 2004. “Patterns of Representation: Dynamics of Public Preferences and Policy.” The Journal of Politics 66 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2508.2004.00139.x.

- Wollmann, H. 2008. “Reforming Local Leadership and Local Democracy: The Cases of England, Sweden, Germany and France in Comparative Perspective.” Local Government Studies 34 (2): 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701852344.