ABSTRACT

This paper draws on the breadth of Forest School research literature spanning the past ten years in order to categorise theorisations across the papers. As Forest Schools in the UK are still a fairly recent development research is still limited in quantity and can lack theorisation at a broader level of abstraction. The systematic literature review draws largely on the framework produced by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) ([2019b]. What is a Systematic Review? Accessed: 13 August 2020. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=67). The paper highlights a set of overarching themes for Forest School research as well as providing a conceptual map representing three distinct contexts: early years, special education needs and disability, and formal education. In addition, a set of more abstract themes emerged from work associated with the Forest School space.

Introduction

Forest School is a popular outdoor education initiative with international reach. Evolving from a diverse range of backgrounds, work under the Forest School label has overarching aims that encourage children to develop various personal qualities in natural learning environments (Cree and McCree Citation2012). However, the literature on Forest Schools presents a range of different (and sometimes competing) approaches, revealed through a range of methods and foci. For example, whilst some studies focus on the potential impact natural spaces have on mental health, others focus on the potential of the outdoors to offer a more efficacious alternative to classrooms as learning spaces. Using a broadly systematic approach, this paper reviews the oeuvre of journal papers to identify the different approaches to Forest School research and the various claims they make to efficacy. It will conclude by considering possible lacunae within the existing body of work to suggest the development of new methodologies within the field.

Table 1. Quantitative research reference.

Table 2. Qualitative methodology: Summary of articles and references reviewed.

There is a significant level of heterogeneity within the activities undertaken under the Forest School banner. This is problematic when attempting to unravel what makes Forest Schools unique from other outdoor learning experiences. The rationale for this review is to capture this heterogeneity but also to establish underlying themes in the research to date. The review does not attempt to define what constitutes a Forest School: it takes researcher identification of Forest School activities as its starting point. As such, the literature itself defines what constitutes a Forest School. Whilst examining work that explicitly acknowledges a focus on the topic, the review recognises that these activities sit within a wider range of outdoor learning that has a longer history and, subsequently, a larger body of research literature to draw on. Forest School literature is therefore located within the wider outdoor learning context where there is a crossover of conceptual ideas.

The systematic approach draws largely on the framework produced by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) (Citation2019b). As a relatively new phenomenon, research on Forest Schools is still limited in quantity and lacking theorisation at a broader level of abstraction (Merton Citation1967). By this, we mean that a consistent set of overarching theories is not evident in the body of work on Forest Schools. By adopting a more consistent approach to selecting and reviewing the literature, we therefore aim to ensure we have captured the breadth of writing on Forest Schools and to categorise the various theorisations that have developed about them.

Methodology

According to the EPPI Centre, a systematic approach is a process whereby:

▪ explicit and transparent methods are used;

▪ a standard set of stages are followed;

▪ accountable, replicable and updatable methods are employed. (Citation2019b)

▪ To identify key methodologies that have been employed in Forest School research

▪ To identify key themes that can be deduced from Forest School literature

▪ To identify opportunities for development in methodological approaches

▪ To identify opportunities for theoretical development

Rules were generated for search criteria that aimed to capture a fair representation of the breadth of work, whilst also establishing appropriate boundaries for what constitutes Forest School activities and what does not. We were specifically interested in up-to-date empirical work. For this reason, we chose to focus only on published journal articles from the last ten years. We also used Boolean operators to ensure the articles identified included the specific phrases ‘Forest School’ and ‘Forest Schools’. We used the ‘Discovery’ search engine, also used by Liverpool John Moores (LJMU) Library Services (available online through the LJMU website). The tool provides comprehensive access to published educational journal articles.

The systematic approach has been criticised, however, for being too reductionist and potentially leading to limited findings (MacLure Citation2005). Therefore, whilst we aimed to provide general rules to achieve consistency, we also allowed for some flexibility in terms of the inductive-deductive process and theory generation. Specifically, we attempted to fit the middle-range theories generated by the research (Merton Citation1967) within a wider theoretical framework, predicated on the concept of space (Lefebvre Citation1979; Massey Citation2005; Agnew Citation2011; Nairn, Kraftl, and Skelton Citation2017).

Finally, we used the Narrative Empirical Synthesis approach (EPPI Centre Citation2019a) to synthesise mapping into a table of structured summaries. We thus developed an overview of the scope of research methods being employed in the field as well as identifying significant trends. Criteria used for mapping were: research paradigm, sample size and methods. Finally, a thematic approach was utilised to identify emerging concepts and prominent ideas that underpin this empirical work. Keywords from findings were identified and grouped in an inductive-deductive fashion based on groupings of keywords against the overarching theoretical framework (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007).

Findings

The relative paucity of literature that this review yielded is noteworthy. In total, our search found 25 articles on the topic of Forest Schools. We do not believe this represents an appropriate level of scrutiny for an initiative that has had a significant impact in the UK and has international reach. The literature was heavily biased towards qualitative methods, with all papers undertaking primary research adopting this methodology, at least in part. Research also tended to be small-scale.

The empirical work on Forest Schools can be broken down into five loose categories: small-scale phenomenological studies; thematic case studies; theoretical papers; mixed methods approaches and literature reviews. It should be noted that this categorisation is very much the authors’ work and, whereas some papers use similar terms (e.g. phenomenology, case study), others have been categorised by the authors based on methodological characteristics.

The phenomenological categories involve low numbers of participants but reveal lived experiences through thick, rich descriptions (Denzin Citation2011). For example, Bradley and Male’s paper (Citation2016) focuses on the experiences of four children with autism who attended a Forest School. Such papers are characterised by the way they attempt to recreate the world from the participants’ perspective. To achieve this, they emphasise contextualised observations and open-ended interviews (e.g. Coates and Pimlott-Wilson Citation2019).

Similarly, literature categorised as case studies focused on participant experience but took a more externalised view i.e. they did not attempt to recreate experiences with the same level of detail. Rather, these studies tended to have larger numbers of participants and focused more on thematic analysis or a single theme. For example, Marioara et al’s paper examines the effect Forest Schools can have on pupil attitudes towards the environment (Marioara, Moş-Butean, and Holonec Citation2016). Data was gleaned from questionnaires completed by 106 pupils and 15 teachers. As such, detail was sacrificed in favour of more generalisable insights around a single theme.

Mixed methods papers tended to generate larger samples and contained some quantitative analysis. It should be noted that these samples were still relatively small. Only three studies had more than 100 participants; one had almost 300 questionnaire responses (Haq and Sarah Citation2014; Turtle, Convery, and Convery Citation2015; Marioara, Moş-Butean, and Holonec Citation2016). As with the previous case study categorisation, each of these papers focuses on the potential impact Forest Schools have on student attitudes towards the environment, with each finding a positive correlation between Forest School attendance and positive environmental attitudes. All provide some qualitative examples of responses but lack the level of detail provided by the smaller scale qualitative pieces. It is worth noting that changing environmental attitudes is the only theme covered in these larger-scale data sets. Although relevant, it represents a narrow focus, and extending the scope of this type of research is worthy of consideration.

Finally, there are a number of works that do not use self-generated research data. One of these is a literature review, which provides a narrower focus than the current paper (the review samples 11 papers about Forest Schools). There are also four pieces that we collectively describe as theoretical and take different forms. Whilst some of the papers provide theoretical arguments about aspects of Forest Schools, others offer a critique of the approach (e.g. Leather Citation2018). One paper can be described as anecdotal, relying heavily on the personal experiences of the author (Mckinney Citation2017).

Conceptual map

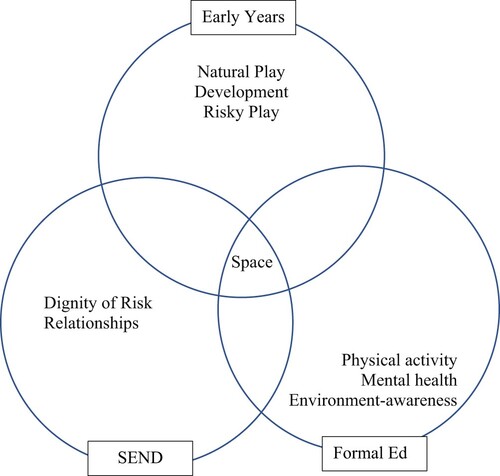

A number of themes were identified from a range of academic fields. Whilst all of these relate to outdoor learning, they represent three distinct contexts: early years, special education needs and disability, and formal education. In addition, a set of more abstract themes emerged from work associated with space. These themes are mapped in below.

The contexts and themes identified within the literature on Forest Schools are historical. For example, early years education has developed outdoor learning as a focus for practice, particularly concerning the importance of outdoor play to early child development (Davies Citation2018). Similarly, a body of historical work has concentrated on the importance of outdoor learning for children with special educational needs and disabilities because of the opportunities such contexts provide for children to experience risk (Perske Citation1972). This interaction between context and themes is important, because such relationships are not necessarily transferable. For example, what is desirable in early years settings might not be desirable in other educational settings. It is notable that broader theorisations of outdoor learning, specifically those associated with space, are more rarely utilised in the literature, with only three articles referring to these concepts in any sustained fashion (see Cumming and Nash Citation2015; Harris Citation2018; Mycock Citation2019). We posit that this is an area that requires more specific attention for those writing about Forest Schools because more abstract theorisations, such as spatialisation, provide opportunities for a broader, more distributed discussion that is not constrained by historical discourses associated with given contexts (Foucault Citation1972). The focus on certain educational contexts is particularly significant because accepted practices within a given setting affect what is perceived as possible and therefore fixes the scope of the theoretical lens through which activities are interpreted. For example, the strong focus on play in early years research is diminished in other school settings where play may be less acceptable as part of general pedagogical practice.

Risk

The relationship between Forest School environments and risk is a significant theme in the corpus. The papers that focus on the topic are spread out across the identified educational contexts. In total, six papers include the keyword ‘risk’. One example focuses on the potential for Forest Schools to enhance risk-taking amongst young children with autism (Bradley and Male Citation2016). A second focuses on ways in which risk was managed in two mainstream primary school groups (Coates and Pimlott-Wilson Citation2019). A third paper examines perceptions of risk amongst parents and practitioners in an early years setting (Savery Citation2017). In addition, two papers focus on the Forest School setting itself. One of these papers is a positional piece, arguing for the need to provide children with more opportunities for risky play in a society that has become predominantly risk-averse (Harper Citation2017). The final two papers focused on the roles of Forest School practitioners and the relationship between perception of risk and practice (Connolly and Haughton Citation2017; Harris Citation2018). These papers did not specify a single group or context.

It is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the small number of articles that cover such a wide range of contexts. However, some tentative judgements can be made about these works within the wider historical context of outdoor learning. With reference to Bradley and Male’s paper (Citation2016), discourses of dignity of risk have been applied to disability and the outdoor learning context since Perske first developed the concept (Citation1972). More recently, the term has been synonymous with contexts that involve children defined as vulnerable. For example, the concept is evident in guidance encouraging outdoor activities in residential child-care (‘Go Outdoors!’ Citation2010). The document generates an equivalence between children ‘who are among the most vulnerable in society’ (Citation2010, 10) and a lack of ‘access to some of the opportunities which other young people take for granted’ (Citation2010, 10). In doing so, children from vulnerable backgrounds are denied access to challenging experiences that may help them to overcome ‘some of the adversities they have faced in their life’ (Citation2010, 10). ‘Dignity of risk’, therefore, can be seen as a term that tends to be located within contexts associated with vulnerable children, such as those with special educational needs, disability and those that suffer severe deprivation.

The concept of risk is applied in different ways within the contexts of early years and formal education. The work of Savery (Citation2017), which emphasises the importance of risk-taking activity in Forest Schools by younger children, can be situated within the substantial history of linking child development to outdoor play in early years settings (McMillan Citation2019). As such, risk is presented as an inevitable outcome of outdoor play and is, therefore, a necessary part of child development. Conversely, research conducted by Coates and Pimlott-Wilson (Citation2019) alludes to the complexity involved in talking about risk within a primary school context. Here, the concepts of ‘dignity of risk’ and ‘risky play’ cannot be applied straightforwardly. Primary schools have not historically placed such a strong emphasis on play and thus the link between classroom-based activity and risk is a more complex one.

In this sense, the more theoretical lens offered by Harper’s positional paper on Forest Schools and risk is significant (Citation2017). In this work, the concept of risk is presented as both a benefit of Forest Schools and as a barrier to them. In the first instance, risk is presented as a deficit: it is something that has been reduced for young people through lower levels of exposure to outdoor environments compared to previous generations. Harper contrasts risky activity with a ‘risk society’ (Citation2017, 318). This term refers to the historically specific conditions that have led to a society ‘accustomed to ever-present and growing perceptions of risk’ (Citation2017, 319). Harper posits that this reduction in tolerance to risk is undesirable and leads to negative social outcomes. Reasons for the deficit tend to focus on a more risk-averse culture and the increase in opportunities for indoor, technology-based activities (Elliott Citation2015). Harper presents a society that is over-aware of risk and in which perception of risk is skewed: what is construed as risk is of minimal danger in relation to other aspects of everyday life. This milieu, Harper argues, is detrimental to healthy child development (Citation2017). In effect, Harper addresses the issue of risk in Forest Schools in a more direct manner than more contextualised research papers on the topic. We argue that, whilst such a theoretical approach provides the freedom to provide a clear rationale for the need for risk in Forest Schools, it provides little traction for change, as practitioners attempt to accommodate various demands on their roles. Indeed, it is more likely that such papers are aimed at policymakers rather than practitioners.

We posit that, whilst each of these approaches to theorising Forest Schools can be to some extent successful, each limits further developing the Forest School concept. If such initiatives are going to create values beyond the contexts in which they currently operate, an approach is required that moves beyond connecting with pre-existing discourses in given contexts. Whilst this approach has had some traction within SEND and early years settings, the proposed value of Forest Schools is fragmented and limited. As such, it is not clear what Forest Schools do in terms of beneficial risk. Furthermore, when the discourses of ‘dignity of risk’ and ‘risky play’ are deleted from specific contexts, their value is also removed concomitantly and the opportunities to transfer Forest School activities as risk-enhancing become limited. Broader theoretical approaches have the potential to expand our understanding, but rarely have an impact at a practitioner level. For this reason, we propose that a hybridised theoretical model is preferable. This approach will be expanded in the conclusion of this paper.

Development through nature

Reduced contact with nature was a significant theme identified in the literature. This is characterised by conceptualisations that emphasise a contemporary disconnect between society and nature and is often contrasted with a previous golden age of outdoor activity. For example, Smith, Dunhill, and Scott (Citation2018) conducted a review of literature that focused on the positive effects Forest Schools had on developing children’s relationship with nature. The paper sets up a dichotomy between learning inside and learning outside the classroom. Although it is not explicitly stated, a deficit model underpins the paper’s analysis. The work developed four themes on the issue: increased knowledge of nature, improved relationship with the outdoors, pride in knowledge of nature and ownership of the local environment. There is an assumption that these interactions with ‘nature’ are inherently good. This assumption sits within a body of work related to outdoor learning that emphasises a contemporary disconnect between society and nature and, as noted earlier, is often contrasted with a previous golden age of outdoor activity (Meier and Sisk-Hilton Citation2013).

Similarly, Turtle, Convery, and Convery (Citation2015) investigated the development of environmental attitudes following participation in Forest Schools, specifically addressing the idea that, by taking part in long-term Forest School activities, children would develop pro-environmental attitudes. Data was taken from questionnaires sent out to primary schools, some of which had Forest Schools and some of which did not (n=195). The paper concluded that there was a significant difference in understanding environmental issues by pupils who had access to Forest Schools. Again, this work links with wider discourses within the field of outdoor learning that emphasise the importance of sustainability (Humberstone, Prince, and Henderson Citation2015). This approach has potential crossover with formal curriculum arrangements and therefore has potential traction within the primary school context. However, the paper does not allude to reasons why Forest School spaces might be more effective than indoor spaces when developing an understanding of environmental issues. As such, it is difficult to establish whether it is the Forest School per se that is effective or whether such issues are addressed more regularly in Forest School environments.

Child development, constructivism, play and sharing

A significant number of research papers on Forest Schools make overt links with theories of cognitive development. Much of this work focuses on constructivist principles of learning and specifically references the historical works of Piaget and Vygotsky. For example, Coates and Pimlott-Wilson (Citation2019) make links to the purported benefits of play in outdoor environments. However, there is a consistent disconnect between constructivist theoretical models and their application to empirical data across the Forest Schools literature. For example, Dillon (Citation2005) identify potential cognitive benefits of outdoor learning theoretically but frame their findings in terms of curriculum knowledge and understandings of natural environments as well as self-esteem. In this instance, the work highlights the significance of the quality of outdoor spaces in the learning process. Again, this is linked to constructivist principles, whereby the interaction between children and outdoor environments leads to new understandings (Kahn and Press Citation1999). However, such claims to beneficial outcomes also tend to become conflated with curriculum-based outcomes or with outcomes relating to understandings of nature. This tends to make causal relationships ambiguous i.e. it is difficult to ascertain how outdoor play directly causes improved curriculum-based outcomes.

Given this disconnect between theory and application, we recommend a more experiential approach to theorisations of Forest Schools and outdoor learning in general. That is, rather than seeing outdoor spaces as sites where children ‘develop’, we see them as spaces where children ‘experience’. By this, we mean that breadth of experience is desirable and easier to identify within complex environments such as outdoor spaces. We argue that, while not impossible, it is very difficult to set up valid research in outdoor environments that would reveal any form of cognitive development, whereas experience can be observed directly through the various interactions (socially and otherwise) that occur in outdoor spaces.

Increased self-esteem and wellbeing

There is a strong focus on the positive effects Forest Schools have on wellbeing within the domain of compulsory education, particularly in primary schools. For example, Cumming and Nash (Citation2015) use a case study methodology to describe the positive effects a ‘bush school’ had on children in a primary school setting, through the development of a connection with place. The findings of this study are organised thematically around a theoretical model that proposes that a connection with the natural environment is essential to the formation of a sense of community and, consequently, the development of a sense of belonging (Cumming and Nash Citation2015, 302).

Similarly, McCree, Cutting and Sherwin’s longitudinal study focused on the impact of Forest Schools on the wellbeing of 11 children who were ‘struggling to thrive’ (Citation2018, 982). Although the paper is not specific about what this phrase means, they state that the participants had a variety of identified issues including economic, emotional and special educational needs (Citation2018, 982). Using a mixed methodology, the study establishes that the Forest School project a) strengthened the participants’ connection with nature; and b) that this improved connection correlated with increases in academic attainment that were above expected levels. The paper also offers insights into the possible connection between these findings through the analysis of qualitative data. Here, the researchers identified that a greater connection with nature led to ‘self-regulation and resilience through emotional space’ (Citation2018, 986), which potentially led to gains in attainment.

Research by Tiplady and Menter (Citation2020) provides a stronger focus on the link between Forest Schools and children unable to attend school due to anxiety or other emotional issues (Citation2020, 2). It crosses over into the realm of special educational needs while maintaining a narrower focus on emotional wellbeing that is commensurate with the other studies that deal with this theme. It is also noteworthy that the study covers two cases, one with primary aged and one with secondary aged children. This demonstrates a broader range of participants but also one that overlaps with the previous studies identified in this paper. As with the study by McCree, Cutting and Sherwin, the study links wellbeing with potential learning gains, in this case focusing on participants’ ‘ready to learn’ skills (Tiplady and Menter Citation2020, 4).

Relationships

Some literature, particularly those that examined interactions between children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD), focused on the opportunities Forest Schools provided for developing new friendships. As such, this aspect of Forest Schools is presented as something of a deficit model: Forest Schools provide opportunities for interactions that do not (or cannot) occur in classroom settings. For example, Bradley and Male (Citation2016) found that children with ASD valued the new friendships they had formed when engaging with Forest Schools. This was also observed as important by education professionals working with these children due to the complex social and emotional needs involved.

Similarly, Coates and Pimlott-Wilson (Citation2019) identified that interactions with peers were the most frequently discussed learning opportunities for their participants, particularly for an older group of children. In this study, Forest Schools provided opportunities for collaborative working and team-building skills in ways that did not seem possible in a classroom setting. Through child interviews, the classroom setting was presented as an individual endeavour and peer collaboration was limited.

For ease of comparison and to highlight content, our literature review is presented below in tabular form, under the headings: Article, Method, Keywords, Credibility/Trustworthiness, Relevance and Findings.

Conclusion

This review has highlighted the context-specific nature of current research on Forest Schools. The process of generating theories from a given context is essential to any research (Burawoy Citation2009). Whilst we see this as having value within the identified domains, we feel that the oeuvre tends to be self-limiting. We argue that wider theorisation is needed to ensure insights can transcend a specific domain (Burawoy Citation2009). Without these more generalisable theories, the knowledge produced tends to be applicable mainly within the identified domains. In the case of Forest Schools, we argue that this is a problem; it means that such activities will remain on the periphery of the core activities of our education system. For example, the literature has established positive links between Forest Schools and wellbeing, and some studies have extended this to link Forest Schools with wellbeing and attainment. Whilst this is valid, it generates a milieu whereby Forest School activities are required to fit within prerequisite classroom-based discourses. We argue that a more effective approach would be to create a greater balance between formal learning discourses (and associated instrumentation) and discourses associated with wellbeing.

We argue that a focus on space in future research would generate new complexities around the broader concepts that allow us to explore hybrid spaces constituted by both classrooms and Forest Schools. By this, we mean an examination of the various interactions between children, adults and artefacts that come together to generate existing and new spaces. By comparing, for example, classrooms with Forest Schools as constructed places, we propose that it is possible to identify continuity and distinctiveness. Such an approach would open up the possibility of Forest School interactions existing within classroom spaces as well as vice versa. We argue that the essential quality of Forest Schools is their relatively ambiguous nature: they provide opportunities for children to negotiate their interactions using processes garnered from a range of experiences, including those encountered in formal education. As such, they can be brought back into formal learning environments in ways that benefit those environments and thus become fundamental, rather than peripheral to shifts in formal practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Bibliography

- Agnew, J. 2011. “Space and Place.” In Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, edited by J. Agnew, and D. Livingstone, Chap. 23, 316–330. London: Sage.

- Bradley, K., and D. Male. 2016. ““Forest School is Muddy and I Like it”: Perspectives of Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, Their Parents and Educational Professionals.” 34 (2): 80–96.

- Burawoy, M. 2009. The Extended Case Method: Four Countries, Four Decades, Four Great Transformations, and One Theoretical Tradition [Paperback]. London: University of California Press.

- Coates, J. K., and H. Pimlott-Wilson. 2019. “Learning While Playing: Children’s Forest School Experiences in the UK.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1002/berj.3491.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research methods in education. [electronic resource].

- Connolly, M., and C. Haughton. 2017. “The Perception, Management and Performance of Risk Amongst Forest School Educators.” British Journal of Sociology of Education. Routledge 38 (2): 105–124. doi:10.1080/01425692.2015.1073098.

- Cree, J., and M. McCree. 2012. A Brief History of the Roots of Forest School in the UK. pp. 32–34. www.outdoor-learning.org.

- Cumming, F., and M. Nash. 2015. “An Australian Perspective of a Forest School: Shaping a Sense of Place to Support Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 15 (4): 296–309. doi:10.1080/14729679.2015.1010071.

- Davies, R., et al. 2018. “‘Assessing Learning in the Early Years ‘ Outdoor Classroom : Examining Challenges in Practice Examining Challenges in Practice’.” Taylor & Francis 4279. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1194448.

- Denzin, N. K. L. Y. S. 2011. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. doi:10.1177/1354067(07080505.

- Dillon, J., et al. 2005. ‘Engaging and Learning with the Outdoors – The Final Report of the Outdoor Classroom in a Rural Context Action Research Project’, (April), p. 90.

- Elliott, H. 2015. “Forest School in an Inner City? Making the Impossible Possible.” Education 3-13 43 (6): 722–730. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.872159.

- EPPI Centre. 2019a. Publications on systematic review / evidence synthesis methodology. Accessed 19 August 2020. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Publications/Methodsreferences/tabid/1919/Default.aspx.

- EPPI Centre. 2019b. What is a Systematic Review? Accessed: 13 August 2020. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=67.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge; And, The Discourse on Language. Leek: Colophon books.

- ‘Go Outdoors!’. 2010. pp. 1–18. papers3://publication/uuid/163F231B-61B6-438A-B2F1-DB36BB3A9347.

- Haq, N., and B. Sarah. 2014. “Perceptions About Forest Schools: Encouraging and Promoting Archimedes Forest Schools.” Educational Research and Reviews. Academic Journals 9 (15): 498–503. doi:10.5897/err2014.1711.

- Harper, N. J. 2017. “Outdoor Risky Play and Healthy Child Development in the Shadow of the “Risk Society”: A Forest and Nature School Perspective.” Child and Youth Services 38 (4): 318–334. doi:10.1080/0145935X.2017.1412825.

- Harris, F. 2018. “Outdoor Learning Spaces: The Case of Forest School.” Area 50 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1111/area.12360.

- Humberstone, B., H. Prince, and K. A. Henderson. 2015. Routledge International Handbook of Outdoor Studies. Oxford: Taylor & Francis (Routledge Advances in Outdoor Studies). https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=oJj4CgAAQBAJ.

- Kahn, P. H., and M. I. T. Press. 1999. The Human Relationship with Nature: Development and Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=PwlCc4Qzo9EC.

- Leather, M. 2018. “A Critique of Forest School: Something Lost in Translation The Growth of Forest School in the UK.” Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 21 (1): 1–11.

- Lefebvre, H. 1979. “Space: Social Product and use Value.” In Critical Sociology: European Perspectives, edited by J. Freiberg, 185–195. New York: Irvington (Irvington Critical Sociology Series). https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=envpAAAAIAAJ.

- MacLure, M. 2005. ““Clarity Bordering on Stupidity”: Where’s the Quality in Systematic Review?.” Journal of Education Policy - J EDUC POLICY 20: 393–416. doi:10.1080/02680930500131801.

- Marioara, I., A. Moş-Butean, and L. Holonec. 2016. Forest School. A Modern Method in Educational Process. http://journals.usamvcluj.ro/index.php/promediu.

- Massey, D. B. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- McCree, M., R. Cutting, and D. Sherwin. 2018. “The Hare and the Tortoise go to Forest School: Taking the Scenic Route to Academic Attainment via Emotional Wellbeing Outdoors.” Early Child Development and Care. Taylor & Francis 188 (7): 980–996. doi:10.1080/03004430.2018.1446430.

- Mckinney, K. 2017. Adventure Into the Woods: Pathways to Forest Schools. Harnessing the Power of Adventure. Pathways 24–27.

- McMillan, M. 2019. The Nursery School. Wyoming: Creative Media Partners, LLC.

- Meier, D. R., and S. Sisk-Hilton. 2013. Nature Education with Young Children: Integrating Inquiry and Practice. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=jEE8m-wYiE4C.

- Merton, R. K. 1967. On theoretical sociology: five essays, old and new. Free Press (Free Press paperback). https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=woFqAAAAMAAJ.

- Mycock, K. 2019. “Forest Schools: Moving Towards an Alternative Pedagogical Response to the Anthropocene?” Discourse. Taylor & Francis 0 (0): 1–14. doi:10.1080/01596306.2019.1670446.

- Nairn, K., P. Kraftl, and T. Skelton. 2017. Space, Landscape and Environment. New York: Springer Singapore (Space, Landscape and Environment).

- Perske, R. 1972. “Dignity of Risk and the Mentally Retarded.” Mental Retardation. US: American Assn on Mental Retardation 10 (1): 24–27.

- Savery, A., et al. 2017. “Does Engagement in Forest School Influence Perceptions of Risk, Held by Children, Their Parents, and Their School Staff?” Education 3-13 45 (5): 519–531. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1140799.

- Smith, M. A., A. Dunhill, and G. W. Scott. 2018. “Fostering Children’s Relationship with Nature: Exploring the Potential of Forest School.” Education 3-13 46 (5): 525–534. doi:10.1080/03004279.2017.1298644.

- Tiplady, L. S. E., and H. Menter. 2020. “Forest School for Wellbeing: an Environment in Which Young People Can “Take What They Need”.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. Routledge 00 (00): 1–16. doi:10.1080/14729679.2020.1730206.

- Turtle, C., I. Convery, and K. Convery. 2015. “Forest Schools and Environmental Attitudes: A Case Study of Children Aged 8-11 Years.” Cogent Education. Cogent 2 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2015.1100103.