ABSTRACT

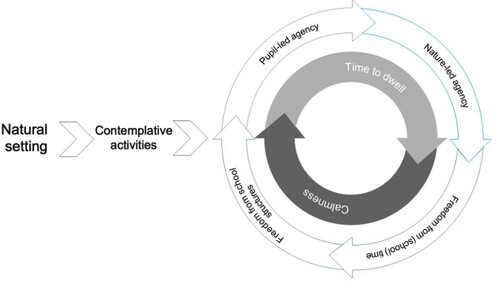

Literature suggests a positive impact on children’s health and wellbeing from being in nature. This study explores primary teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ (7–11 years) experiences of contemplative approaches in nature reserve settings. Nine teachers from a convenience sample of eight different primary schools took part. After observing pupils undertake a range of contemplative activities, teachers were interviewed individually. They perceived an increase in agency (child-led and nature-led), a sense of freedom (from school structures and school time), a sense of calmness and a resultant time to dwell, summarised in a new model.

It has been over fifteen years since Louv (Citation2005) asserted that children were suffering from nature deficit disorder, despite the fact that contact with nature can provide many benefits for children (Chawla Citation2015). Pyle (Citation2011) argued that modern society was causing ‘the extinction of experience’ as children were being deprived of experiencing the ‘wholeness’ one can experience in nature places (Pyle Citation2011, 134). Over the past decade, there has been an increasing body of literature providing evidence about the positive impact nature, in so-called green spaces, can have on children’s health and wellbeing (Faber Taylor and Kuo Citation2011; Malone and Waite Citation2016; Ward et al. Citation2016). There is also evidence that suggests more biodiversity in urban spaces can increase children’s wellbeing (Birch, Rishbeth, and Payne Citation2020; Hand et al. Citation2017; Taylor and Hochuli Citation2015). Despite this, Bragg et al. (Citation2015, 8) highlight the lack of attention given to the benefits to health and wellbeing of rich natural environments. Lovell et al. (Citation2014) also note there is some evidence to suggest that biodiverse natural environments may have health benefits, but assert the need for more research into these benefits.

This study explores teachers’ perceptions of primary school (aged 7–11 years) children’s experiences of mindful, or contemplative, activities at a nature reserve. The study is contextualised by three main areas of literature: ontological states of being; alternative pedagogical approaches; and alternative ways of knowing. The pedagogical approaches and ways of knowing are positioned as being alternative, because they contrast with the current types of knowledge and pedagogical practices that dominate mainstream schooling in the West (Bonnett Citation2019; Jardine Citation2016).

Review of literature

Demand for outdoor educational experiences is growing (Quay et al. Citation2020; Waite Citation2020). In the United Kingdom (UK), where this research took place, the curricula of the four nations (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales) include a statutory requirement for schools to deliver outdoor education (Adams and Beauchamp Citation2019). In this context, outdoor learning provision has increased in the UK (Harris Citation2021). However, evidence suggests schools are not all prioritising outdoor educational experiences due to accountability pressures (Thorburn and Allison Citation2013; Waite Citation2010). In addition, it is argued that the ethos and underpinning philosophy of many philosophies of outdoor education are in tension with mainstream curricula which is ‘driven by neo-liberal policies based on accountability and measurement’ (Kemp Citation2020, 370). Others also bemoan limited outdoor pedagogical perspectives in curricula, declaring that even so-called environmental education tends to ‘de-nature nature’ (Selby Citation2017) provision. Mitten (Citation2017) argues that too often nature is used as a proving ground to demonstrate competency or provide controlled risk. Furthermore, Mannion and Lynch (Citation2015, 86) contend that outdoor educational experiences either ‘privilege the cognitive reflective process’ (where the activity is a method for some sort of later improvement) or prioritise the intrinsic benefit of the activity itself. Nicol (Citation2013, 450) also explains that the ‘activities become ends in themselves’. Even though outdoor education may be ‘inherently nature-based’, this does not mean that it is ‘necessarily nature-attentive’ (Nicol Citation2013, 458).

Nature is thus commodified as something that has only instrumental or utilitarian value, reflecting the view of humans as being separate from, and dominant over, nature (Wilson Citation2019). Instead, we should be seeking ‘the kinds of educational experiences that allow learners to sustain new ways of being in the world’ (Jickling and Sterling Citation2017, 16), rather than seeing nature as a resource, or a means to an end. Barnes (Citation2018) similarly argues we need to put children in situations that encourage awe and wonder.

Ontological states of being

To achieve this, our relationship with nature needs to be at the heart of a recalibration of education (Bonnett Citation2017a; Jickling and Sterling Citation2017; Jardine, Clifford, and Friesen Citation2015; Jickling et al. Citation2018). Bonnett (Citation2017a, 333) claims that ‘education itself, properly understood, is intimately concerned with an individual’s being in the world’. This perspective is grounded in a phenomenological philosophy that believes human existential understanding is rooted in experience when one ‘attends to the very occurring of things’ (Bonnett Citation2017b, 83). When this reality is attended to, we may experience the interrelatedness inherent in the natural world.

Others also support the claim that our authentic essence can be experienced in nature and this entails a different ontological reality or state of being. Beeman and Blenkinsop (Citation2008) highlight how indigenous peoples have different perspectives of reality in comparison to those experienced in the West. They explain how an Anishinaabe Elder ‘understands and enacts the self as not stopping at the skin/air interface, but extending into a larger sphere of interaction and interdependence with the more-than-human-world’ (Beeman and Blenkinsop Citation2008, 97). Similarly, Abram (Citation2010, 63) asserts that we sense the world as ‘we are wholly embedded in the depths of the earthly sensuous’. These knowings are embodied and felt, and the knowledge is experienced at the moment rather than processed after the event (Pulkki, Dahlin, and Värri Citation2017).

Alternative pedagogical approaches

Such ways of knowing contrast with the rational cognitive knowings that dominate Western education (Bonnett Citation2017a; Dickinson Citation2013), where concepts such as ‘indoorism’ (Orr Citation2004) and ‘cerebralization’ (O’Riley and Cole Citation2009) have featured in concerns about contemporary schooling. Bai (Citation2009) therefore calls for curricula to allow children to be in mindful contact with nature as ‘soil renewal is soul renewal, and every mindful contact we make with the ground restores humanity’ (147). Bonnett concurs stating that curricula too often overlook ‘the knowledge we possess through bodily contact with the world’ in favour of ‘abstract generalisation and objectification’ (Citation2004, 98).

These views are supported by Pulkki, Dahlin, and Värri (Citation2017) who argue that even in environmental education curricula ‘the students’ own actual and embodied feelings, thoughts and experiences of nature’ are often ignored (2). They, therefore, advocate contemplative pedagogical approaches.

Contemplative engagement in nature places provides not only sensory attunement, but also has the possibility of revealing a move away from clock-time to a different experience of time (Adams and Beauchamp Citation2021). This new experience of time during contemplative practices is not perceived in a linear, horizontal fashion, but ‘is a qualitative and deconstructive timing which interrupts the line of chronos’ (Seidel Citation2014, 146), to be replaced by Kairos, which is an ‘existential and ontological timing’ (Seidel Citation2014, 146). This has pedagogical significance because it potentially involves a different orientation for education (Ergas Citation2016; Jardine Citation2013) and highlights the potential of contemplative pedagogies, which are about ‘dwelling in the here and now’ (Ergas Citation2016, 58).

Contemplative pedagogies encourage time to wonder, are not beholden to pre-determined outcomes and allow children to move beyond expected outcomes to attend to, and expect, anything (Pulkki, Saari, and Dahlin Citation2015). They also provide a radical alternative to much of current Western education as outcomes are open to doubt and uncertainty (Seidel and Jardine Citation2014).

Alternative ways of knowing

At present, we argue that rationalisation and objectification are dominant features of western educational discourse, resulting in ‘suppressed emotion, a decreased sense of place, and anthropocentrism’ (Dickinson Citation2013, 329). In contrast, it is argued that contemplative practices can afford us with ways of knowing that challenge the dominance of ‘rational-assertive thinking’ (Bonnett Citation2004, 138) in our educational spheres. This is not just because they are valuable as ‘preparation for or enhancement of intellectual learning’ (Ferrer Citation2017, 164). Rather, they have an epistemic value of their own, providing access to somatic, emotional, and intuitive ways of knowing that are often marginalised in western education (Ferrer Citation2017).

Contemplative knowledge is, however, embodied and requires direct attention from all of our senses though an ‘epistemology of attention’ that deepens our understanding of the interrelatedness of things (Pulkki, Saari, and Dahlin Citation2015, 46). This can be attempted inside the classroom, but we suggest it may be better suited to contemplative activities at rich, diverse outdoor settings, such as nature reserves, where children can ‘slow the attention and broaden our relations to the Earth’ (Jardine Citation1996, 51). In this context, we need to see the ‘other-than-human-world as backdrop’, and educators should embrace the other-than-human as ‘a co-teacher’ (Blenkinsop and Beeman Citation2010, 27).

Methodology

This study is an interpretivist, qualitative investigation, which explores primary school teachers’ perceptions of the impact of contemplative activities on their pupils’ experiences at one of two nature reserves (A and B). Both sites offered a similar experience as they were Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and included a bio-diverse combination of wetlands, sand dunes, trees and open spaces providing a rich diversity of tactile habitats, sights, sounds and smells for children to experience.

As this was interpretivist research, it did not aim to support generalisations, but to lead to illumination of an issue (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2003; Kincheloe Citation2012) through deep understanding of a small number of cases. The research undertook a inductive approach, because rather than ‘thick description of all that can be observed’, it was ‘theory driven’ (Bryant and Charmaz Citation2007, 155), focussing on emerging theory from analysis of the data. However, there was also an acknowledgement of multiple realities due to ‘the researcher and research participants’ respective positions and subjectivities’ (Charmaz Citation2011, 68).

The knowledge is therefore situated and the data ‘inherently partial and problematic’ (Charmaz Citation2011, 68). Furthermore, we note Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) assertion that qualitative research is an active process, which is ‘about meaning and meaning-making’ and as such is ‘always context-bound, positioned and situated’ (591). Therefore, after prolonged immersion in the data, this paper is about telling stories (Braun and Clarke Citation2019) of what teachers saw in their children as they responded to the world around them during contemplative activities in biodiverse environments.

Methods and sample

Coburn et al. (Citation2011) note that there is no definitive list of contemplative pedagogies, but this is used as an umbrella term to cover the different activities undertaken by the children. Grace (Citation2011) states that contemplative practices in the classroom include (amongst others): silent sitting meditation; deep listening; and nature observation. The participating children undertook all these contemplative activities whilst at a nature reserve, as well as others. Some of the activities were led by one of the research team and had been planned beforehand. For instance, the children in each class played a hide-and-seek game, in which the rules forbade verbal communication and focussed attention on using other senses, thus encouraging mindful awareness of their surroundings to seek others. Other activities were led spontaneously by children. For example, one of the children picked up sand from a sand dune and began feeling it in their fingers. The other children then also picked up sand so they could feel what it felt like. The research was not intended to focus on any particular activity, but to explore the impact of allowing children to experience a range of contemplative activities in natural settings.

It is important to note that the teachers did not take part in the activities and were thus non-participant observers, able to closely observe children that they knew very well in a new setting. As they all used observation as part of their classroom practice as ‘observations by teachers, … are a key part of their professional practice. Focusing mainly on children’s behaviour and understanding’ (Vrikki et al. Citation2019, 189). They can thus be regarded as complete observers (Baker Citation2006), as they were present at the scene, but did not ‘participate or interact with insiders to any great extent. Her/his only role is to listen and observe’ (Baker Citation2006, 174). Although teachers did not question the children to seek participant confirmation about what they were doing (although they were interviewed by the research team), they were able to offer observations which contextualise behaviours, informed by their very detailed knowledge of these children’s behaviours in school and other settings.

Additionally, most teachers had discussed the trip with pupils when they returned and were able to offer direct insights into what the children had said. It was clear from transcripts that these were informal, unstructured conversations, common in the primary classroom, and that their perceptions were predominantly based on watching children they observed on a daily basis in the classroom as they interacted with nature. As such, they were uniquely placed to comment on the particular impact of the contemplative activities in the natural setting, and it is this ‘insider’ knowledge that is explored in this paper.

Nine teachers from a convenience sample of eight different primary schools took part in the study. The children (n = 201) were aged between 7 and 11 years old – .

Table 1. Sample of teachers interviewed.

Prior to any activities, this study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Cardiff Metropolitan University. After their visits to the nature reserve, a representative random sample of the children undertook small group interviews, but all the teachers were interviewed individually. All interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. This paper reports only on the teacher interviews and the pupil perspectives are reported elsewhere (Adams and Beauchamp Citation2021).

Analysis procedure

Analysis of teacher interview data began with an inductive approach that involved open coding, whereby the recorded interviews were scrutinised, aiming ‘to produce concepts that seem to fit the data’ (Strauss Citation1987, 28). The aim was not to reduce the data to some ‘general, common denominators’, but rather ‘to expand, transform, and reconceptualize’ the data, thereby ‘opening up more diverse analytical possibilities’ (Coffey and Atkinson Citation1996, 29).

Both members of the research team coded the interview transcripts independently. These initial codes were ‘tools to think with’ (Coffey and Atkinson Citation1996, 32), and thus not set-in-stone. We then met to discuss our initial analyses. This involved re-reading the transcripts and comparing notes. The codes were then ‘clustered into themes’ that were ‘interpreted according to relevant theory (O’Connor and Joffe Citation2020, 2). Visual models, or diagramming (Nowell et al. Citation2017), of the emerging themes were also constructed, shared and revised during subsequent meetings. The coding analysis was a ‘cyclical act’ (Saldaña Citation2015, 8) moving back and for between the data and theory. Sipe and Ghiso (Citation2004, 482–483) highlight that this iterative process inevitably involves judgment calls as we bring ‘our subjectivities, our personalities, our predispositions, [and] our quirks’ to the process. We were also mindful of Saldana’s (Citation2015, 6) caution that ‘Coding requires that you wear your researcher’s analytic lens. But how you perceive and interpret what is happening in the data depends on what type of filter covers that lens and from which angle you view the phenomenon’. In this context, the analysis acknowledges Bonnett’s philosophy of education (Citation2017b, Citation2019) and various perspectives on contemplative pedagogy (Ergas Citation2016; Jardine, Clifford, and Friesen Citation2015; Pulkki, Saari, and Dahlin Citation2015; Seidel and Jardine Citation2016).

Results and analysis

The result of the analysis was the generation (Braun and Clarke Citation2020) of four main themes and related sub-themes, discussed in turn below:

Agency:

o child-led

o nature-led;

Freedom:

o from school structures

o from (school) time;

Calmness;

Time to dwell.

Agency: child-led; nature-led

All the teachers consistently reported that they felt the pedagogical activities facilitated by the nature reserve and the contemplative activities provided pupils with greater agency. This included allowing more freedom for things to be child-led and spontaneous. For example, Teacher T reported the benefits of ‘wandering around a nature reserve without an end goal … you know, having that time to kind of explore that is really nice’. Teacher L echoed these thoughts saying: ‘When I came back, I felt it was one of the best school trips I’ve done, probably less structured … We pretty much … went with the children and their engagement levels’.

Teachers noted the result of greater pupil agency was that ‘they had the freedom of being able to explore what was around them and they wanted to know more’ (Teacher C). Teacher S1 summed this agency up as

I think having the freedom to do, ‘Right we’re just going to run up the hill’ or, ‘We’re just going to run down the hill’, ‘Go for it! Whatever you want to do, you’re in charge, you’re responsible for yourself, off you go’. (Teacher S1)

Freedom for the children to learn at their own level and to all succeed, which they did, they engaged, they succeeded, they enjoyed and that’s the main thing, that’s what we want for all our children. (Teacher L)

Teachers were explicit that it was the unique experiences (however apparently mundane) of being in nature that were important, not just being outside doing contemplative activities, for instance in the school grounds. Teacher S1 explained that

I think things like having sand in your shoes when you’ve walked up a sand dune. You have to physically pour it out and it’s on you and you have to like move it away. You’re sitting on the grass, you’re looking at the view, it’s kind of – all the distractions were taken away.

Freedom – from school structures

Teachers strongly perceived freedom from the constraints of structures, which they themselves imposed through the school systems and processes, was a contributing factor to the increased agency. These structures are diverse and include the curriculum, the timetable and systemic assessment. For instance, normally children’s time in school is ‘structured for them … they know this time is literacy, maths, can’t do literacy in maths time because that’s not … you know, they’re so timetabled aren’t they?’ Similarly, teacher C described how

You’re governed by a timetable; they know they’re coming to school, they do Maths, then they do Language, and then they do a project and then they do reading; so, it’s all timetabled.

kind of put it in their [children’s] hands didn’t it, … it wasn’t too prescribed as such so it was up to the children to take it what they … you know, it wasn’t led by outcome (Teacher B).

I give children success criteria all day long … there was no success criteria that they had to meet by the end of the session and maybe that’s enough, that actually to take that success criteria away and let them make their own success criteria.

Freedom – from (school) time

Teachers repeatedly described how that the contemplative activities at the nature reserve had encompassed a different perception of time and that this had a major positive impact on the children’s experiences. They consistently associated the perceived success of the activities to a freedom from the clock-time of the classroom. For example, Teacher T said

in school they always wait for the next thing to do or the next part of their day. And it’s all structured around timings, isn’t it? But outside not one of them asked the time, which is lovely, and you forget about the time because you’re lost in the moment of being outdoors, and you’re not taking notice of what you need to do next, or where we need to be next.

open up and talk about things that they might otherwise try to put to the back of their mind or won’t allow it to come out within a normal classroom setting cos they know they’re too busy doing other things.

Teachers felt their own role contributed to this as ‘we pass on that pressure to children, that our day is boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. We have this many tasks to do, so time, time is a precious commodity’ (Teacher L).

Teachers also reported how their observations made them reconsider their own classroom practice. Teacher S explained that:

I think there is so much that we feel we need to get through, that we kind of miss the point of some of the more important stuff, that we don’t necessarily see as important. … But actually, having time to discover themselves, uncover their feelings and regulate is probably more important.

Calmness

By having agency to respond to their own ideas and stimuli from nature, teachers observed pupils

were definitely more relaxed and calm. I don’t even know if they found it a little bit sleepy some of them, as well, just because they were completely at one with nature, weren’t they? They were almost sort of dreaming, their eyes were closed, and some of them I think could have fallen asleep. (Teacher BC)

Time to dwell

Teachers overserved that this calmness encouraged children to dwell in their surroundings. Teacher D reported that ‘I think they took time to breathe, they didn’t worry or have to be rushed and they were able to explore and think about things without having to think about ‘oh I need to complete things’.

Similarly, Teacher M perceived that

… they [the children] said exactly the same; they said about it feeling somehow more real and they said about feeling good inside, and a different energy they talked about as well. … They can let go and detach from work and worries and stress; it’s just living in the moment.

It is possible to sum up these experiences and their impact on children as a kind of linear progression in showing the relationship of the themes, which will contextualise our discussion.

Discussion

This group of teachers, as expert observers of children they taught daily, reported that the combination of undertaking contemplative activities in the natural environment of a nature reserve had a powerful positive impact on the children’s experiences. They perceived that undertaking contemplative activities in a natural setting enabled children to access ways of knowing that would not have been so accessible in the school environment. These ways of knowing involved sensory, embodied understandings encompassing an enhanced experience of nature. For example, Teacher L said, ‘engaging with nature, using their senses and awareness of their surroundings, the river, the trees … all of that made the trip very different to something you could do just on a school field’. This was reinforced by Teacher T who explained: ‘The fact that we were in a nature reserve, that meant just a completely different set of senses. … they would have picked up on, less noise and so on’.

The idea that the children were ‘led by their senses’ links to Pulkki’s assertion that contemplative approaches have epistemic value, as they allow us to experience ‘our senses in a direct, non-fragmentary experience’ (Pulkki, Saari, and Dahlin Citation2015, 46). The teachers consistently described how the biodiverse environment and contemplative approaches had produced a heightened embodied experience, and that this, in turn, affected the children’s sense of relationship with the other-than-human world. For example, Teacher L said it invoked

a different feeling, … the resistance of the sand as they were walking up and physically that just changes your whole body the fact that you feel, you know, part of where you are.

Teachers noticed their children had potentially accessed a different state of being during the activities at a nature reserve. For example, Teacher S said

They get an understanding that I just don’t exist alone, not just me. … there are other things that happen around me and other people and other beings that are just as important, and that without being mindful in a nature place and feeling that sense of connection it doesn’t work, does it?

The idea that a nature reserve environment, in combination with the contemplative activities, had provided a gateway for children to ontological realisations was repeated throughout the responses of the teachers. They consistently perceived the existential nature of the experiences. This is highlighted by Teacher C stating ‘I think a human being has a connection to nature, but we don’t get the opportunity to do it, and I think that being connected to nature helps them to be more calm, positive, and just in peace with themselves’.

This is also raised clearly by Teacher L who said

I think nature fits with that … Children just need to experience it, experience we’re all co-dependent and interdependent. … I think children are still more in tune with it than we are when given the opportunity.

Limitations

This paper reports on teachers’ perceptions of a relatively small-scale sample of pupils taking part in about the contemplative activities of in a nature reserve setting. As such, we are not trying to make claims beyond this sample, or for particular contemplative activities, although the consistency of teachers’ perceptions between the nine classes from eight different schools suggests this may be worthy of further study.

In addition, the teachers are only reporting their own perceptions of the children’s’ experience and the impact on them. However, they are very similar to those of the children reported elsewhere ( Adams and Beauchamp Citation2021). Furthermore, as teachers are professional, and expert, observers of their children their views are valid and valuable measure of the success of any learning activity.

Conclusion

This study suggests that primary school teachers can see many unique benefits in providing opportunities for their pupils to experience contemplative activities in nature settings. They report that allowing children such experiences in natural settings can provide unique opportunities for children to be liberated from the constraints of school structures and clock-time. This may prove a challenge, but also a liberation, for teachers as they are also freed from restrictions of a curriculum or learning objectives. It is important to note that this cannot be achieved simply by spending more time in nature, or simply by moving classroom learning outdoors. It requires giving children a transformative experience of dwelling in nature, experienced at the moment, free from any preconceived aims or objectives – set by the teacher themselves, the school or the curriculum. In other words, children should learn from nature, not about nature; the focus should be on the child, not the content. This resonates with the Norwegian philosophy of friluftsliv, which ‘first and foremost, is about feeling the joy of being out in nature, alone or with others, experiencing pleasure and harmony with the surroundings, being in nature and doing something that is meaningful’ (Dahle Citation2007, 23). Genuine friluftsliv involves slow experiences, resonating with the feelings of time to dwell and calmness in pupils that were described by teachers. The interviews suggest, however, that this can only happen if teachers relinquish control and allow children and nature to provide stimuli and impetus for action. This suggests the need for a new pedagogy where pupils and nature (not teachers) are given agency to facilitate an interconnectedness with nature. It is therefore important to move away from school structures and expectations, so that children’s experience of nature is not predicated on specific achievements or outcomes, but has intrinsic value in its own right. If this happens, pupils can experience ‘the beauty of the world, like we’re beautiful as well and … that awe and the wonder of creation and I don’t think that often happens at school’ (Teacher S).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abram, D. 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. Toronto: Random House.

- Adams, Dylan, and Gary Beauchamp. 2019. “Spiritual moments making music in nature. A study exploring the experiences of children making music outdoors, surrounded by nature.” International Journal of Children's Spirituality 24 (3): 260–275. doi:10.1080/1364436X.2019.1646220.

- Adams, D., and G. Beauchamp. 2021. “A study of the experiences of children aged 7-11 taking part in mindful approaches in local nature reserves.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 21 (2): 129–138. doi:10.1080/14729679.2020.1736110.

- Bai, H. 2009. “Re-animating the Universe: Environmental Education and Philosophical Animism.” In Fields of Green: Restorying Culture, Environment, and Education, edited by M. McKenzie, P. Hart, H. Bai, and B. Jickling, 135–152. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press Inc.

- Baker, L. M. 2006. “Observation: A Complex Research Method.” Library Trends 55 (1): 171–189. doi:10.1353/lib.2006.0045.

- Barnes, Jonathan. 2018. Applying Cross-Curricular Approaches Creatively. London: Routledge.

- Beeman, C., and S. Blenkinsop. 2008. “Might Diversity Also Be Ontological? Considering Heidegger, Spinoza and Indigeneity in Educative Practice.” Encounters in Theory and History of Education 9: 95–107. doi:10.24908/eoe-ese-rse.v9i0.648.

- Birch, J., C. Rishbeth, and S. R. Payne. 2020. “Nature Doesn't Judge You – How Urban Nature Supports Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Diverse UK City.” Health & Place 62: Article 102296. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102296.

- Blenkinsop, S., and C. Beeman. 2010. “The World as Co-Teacher: Learning to Work with a Peerless Colleague.” The Trumpeter 26 (3): 27–39.

- Bonnett, M. 2004. Retrieving Nature: Education for a Post-Humanist Age. London: Blackwell.

- Bonnett, M. 2017a. “Environmental Consciousness, Sustainability, and the Character of Philosophy of Education.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 36 (3): 333–347. doi:10.1007/s11217-016-9556-x.

- Bonnett, M. 2017b. “Sustainability and Human Being: Towards the Hidden Centre of Authentic Education.” In Post-sustainability and Environmental Education, edited by B. Jickling and S. Sterling, 79–91. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51322-5

- Bonnett, M. 2019. “Towards an Ecologization of Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 50 (4-6): 251–258. doi:10.1080/00958964.2019.1687409.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2020. “One Size Fits all? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Bragg, R., C. Wood, J. Barton, and J. Pretty. 2015. Wellbeing Benefits from Natural Environments Rich in Wildlife: A Literature Review for The Wildlife Trusts, 1–40. Wivenhoe Park: University of Essex. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/sites/default/files/2018-05/r1_literature_review_wellbeing_benefits_of_wild_places_lres.pdf (Accessed on 23rd March, 2022).

- Bryant, A., and K. Chamaz. 2007. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

- Charmaz, K. 2011. “Grounded Theory Methods in Social Justice Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oks, CA: Sage.

- Chawla, L. 2015. “Benefits of Nature Contact for Children.” Journal of Planning Literature 30 (4): 433–452.

- Coburn, Tom, Fran Grace, Anne Carolyn Klein, Louis Komjathy, Harold Roth, and Judith Simmer-Brown. 2011. “Contemplative Pedagogy: Frequently Asked Questions.” Teaching Theology & Religion 14 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1111/teth.2011.14.issue-2.

- Coffey, A., and P. Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. London: Sage.

- Dahle, B. 2007. “Norwegian Friluftsliv: A Lifelong Communal Process.” Nature First: Outdoor Life the Friluftsliv Way, edited by B Henderson and N Vikander, 23–36. Toronto: Dundurn.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2003. The Landscape of Qualitative Research Theories and Issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dickinson, Elizabeth. 2013. “The Misdiagnosis: Rethinking “Nature-deficit Disorder”.” Environmental Communication 7 (3): 315–335. doi:10.1080/17524032.2013.802704.

- Ergas, O. 2016. “The Deeper Teachings of Mindfulness-Based ‘Interventions’ as a Reconstruction of ‘Education’.” In Book Title, edited by O. Orgas and S. Todd. New York: Wiley and Sons.

- Faber Taylor, A., and F. E. Kuo. 2011. “Could Exposure to Everyday Green Spaces Help Treat ADHD? Evidence from Children's Play Settings.” Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 3 (3): 281–303. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01052.x.

- Ferrer, J. N. 2017. Participation and the Mystery: Transpersonal Essays in Psychology, Education, and Religion. New York: Suny Press.

- Grace, Fran. 2011. “Learning as a Path, Not a Goal: Contemplative Pedagogy - Its Principles and Practices.” Teaching Theology & Religion 14 (2): 99–124. doi:10.1111/teth.2011.14.issue-2.

- Hand, K. L., C. Freeman, P. J. Seddon, M. R. Recio, A. Stein, and Y. van Heezik. 2017. “The Importance of Urban Gardens in Supporting Children's Biophilia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (2): 274–279. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609588114.

- Harris, Frances. 2021. “Developing a Relationship with Nature and Place: The Potential Role of Forest School.” Environmental Education Research 27 (8): 1214–1228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1896679.

- Jardine, D. 1996. “Under the Tough Old Stars.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 1 (1): 47–55.

- Jardine, D. W. 2012. Pedagogy Left in Peace: Cultivating Free Spaces in Teaching and Learning. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Jardine, D. W. 2013. “Time is (not) Always Running Out.” Journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies (JAAACS) 9: 2. doi:10.14288/jaaacs.v9i2.187726.

- Jardine, D. 2016. In Praise of Radiant Beings: A Retrospective Path through Education, Buddhism and Ecology. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Press.

- Jardine, D. W., Patricia Clifford, and Sharon Friesen. 2015. “"Under the Tough Old Stars": Meditations on Pedagogical Hyperactivity and the Mood of Environmental Education.” In Curriculum in Abundance , 207–212. London: Routledge.

- Jickling, Bob, Sean Blenkinsop, Marcus Morse, and Aage Jensen. 2018. “Wild Pedagogies: Six Initial Touchstones for Early Childhood Environmental Educators.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 34 (2): 159–171. doi:10.1017/aee.2018.19.

- Jickling, B., and S. Sterling. 2017. Post-sustainability and Environmental Education: Remaking Education for the Future. New York: Springer.

- Kemp, Nicola. 2020. “Views from the staffroom: forest school in English primary schools.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 20 (4): 369–380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1697712.

- Kincheloe, J. 2012. Teachers as Researchers (Classic Edition): Qualitative Inquiry as a Path to Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

- Louv, R. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. New York: Algonquin Books.

- Lovell, R., Benedict W. Wheeler, Sahran L. Higgins, Katherine N. Irvine, and Michael H. Depledge. 2014. “A Systematic Review of the Health and Well-Being Benefits of Biodiverse Environments.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 17 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/10937404.2013.856361.

- Malone, K., and S. Waite. 2016. Student Outcomes and Natural Schooling: Pathways form Evidence to Impact Report 2016. Plymouth: Plymouth.

- Mannion, Greg, and Jonathan Lynch. 2015. “The Primacy of Place in Education in Outdoor Settings.” In Routledge International Handbook of Outdoor Studies. Routledge International Handbooks, edited by Barbara Humberstone, Heather Prince, and Karla A. Henderson, 85–94. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mitten, D. 2017. “Connections, compassion, and co-healing: The ecology of relationships.” In Reimagining sustainability in precarious times , 173–186. Singapore: Springer.

- Nicol, Robbie. 2013. “Entering the Fray: The role of outdoor education in providing nature-based experiences that matter.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 46 (5): 449–461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00840.x.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- O’Connor, Cliodhna, and Helene Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940691989922. doi:10.1177/1609406919899220.

- O’Riley, P., and P. Cole. 2009. “Coyote and Raven Talk About the Land/Scapes.” In Fields of Green: Restorying Culture, Environment, and Education, edited by M. MacKenzie, P. Hart, H. Bai, and B. Jickling, 125–134. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press Inc.

- Orr, D. W. 2004. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Pulkki, J., Bo Dahlin, and Veli-Matti Värri. 2017. “Environmental Education as a Lived-Body Practice? A Contemplative Pedagogy Perspective.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 51 (1): 214–229. doi:10.1111/jope.2017.51.issue-1.

- Pulkki, J., A. Saari, and B. Dahlin. 2015. “Contemplative Pedagogy and Bodily Ethics.” Other Education-the Journal of Educational Alternatives 4 (1): 33–51.

- Pyle, R. 2011. The Thunder Tree: Lessons from an Urban Wildland. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Quay, John, Tonia Gray, Glyn Thomas, Sandy Allen-Craig, Morten Asfeldt, Soren Andkjaer, Simon Beames, etal. 2020. “What future/s for outdoor and environmental education in a world that has contended with COVID-19?.” Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 23 (2): 93–117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00059-2.

- Saldaña, J. 2015. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage.

- Seidel, J. 2014. “Meditations on contemplative pedagogy as sanctuary.” The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry 1 (1): 141–147.

- Seidel, J., and D. W. Jardine. 2014. Ecological Pedagogy, Buddhist Pedagogy, Hermeneutic Pedagogy: Experiments in a Curriculum for Miracles. New York: Peter Lang.

- Seidel, J., and D. W. Jardine. 2016. The Ecological Heart of Teaching: Radical Tales of Refuge and Renewal for Classrooms and Communities. New York: Peter Lang.

- Selby, D. 2017. “Education for sustainable development, nature and vernacular learning.” CEPS journal 7 (1): 9–27. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:12955.

- Sipe, Lawrence R., and Maria Paula Ghiso. 2004. “Developing Conceptual Categories in Classroom Descriptive Research: Some Problems and Possibilities.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 35 (4): 472–485. doi:10.1525/aeq.2004.35.issue-4.

- Strauss, A. L. 1987. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, L., and D. F. Hochuli. 2015. “Creating Better Cities: How Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning Enhance Urban Residents’ Wellbeing.” Urban Ecosystems 18 (3): 747–762. doi:10.1007/s11252-014-0427-3.

- Thorburn, Malcolm, and Peter Allison. 2013. “Analysing Attempts to Support Outdoor Learning in Scottish Schools.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 45 (3): 418–440. doi:10.1080/00220272.2012.689863.

- Vrikki, M., R. Kershner, E. Calcagni, S. Hennessy, L. Lee, F. Hernández, N. Estrada, and F. Ahmed. 2019. “The Teacher Scheme for Educational Dialogue Analysis (T-SEDA): Developing a Research-Based Observation Tool for Supporting Teacher Inquiry Into Pupils’ Participation in Classroom Dialogue.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42 (2): 185–203. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2018.1467890.

- Waite, Sue. 2010. “Losing our way? The downward path for outdoor learning for children aged 2–11 years.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 10 (2): 111–126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2010.531087.

- Waite, Sue. 2020. “Where Are We Going? International Views on Purposes, Practices and Barriers in School-Based Outdoor Learning.” Education Sciences 10 (11): 311. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110311.

- Ward, J. S., J. S. Duncan, A. Jarden, and T. Stewart. 2016. “The Impact of Children's Exposure to Greenspace on Physical Activity, Cognitive Development, Emotional Wellbeing, and Ability to Appraise Risk.” Health & Place 40: 44–50. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.015.

- Wilson, R. 2019. “What Is Nature?.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 7 (1): 26–39.