ABSTRACT

Forest Schools emerged in the UK in the early 1990s after a group of practitioners developed the Forest School programme following a visit to Denmark. In our recent systematic review of forest school literature in England (Garden and Downes Citation2021), we proposed that a focus on space in future research to generate new complexities around the broader concepts that allow us to explore hybrid spaces constituted by both classrooms and Forest Schools. This means an examination of the various interactions between children, adults and artefacts that come together to generate existing and new spaces. There is the opportunity to re-conceptualise ideas around the Forest School space through the framing of Massey’s (Citation2005) proposition that space is a product of relations-between and that space is always in the process of being made. Thus, children create and ‘own’ the Forest School space through their inhabitation of it. This paper provides a key contribution to existing knowledge around Forest Schools within outdoor education by examining ways in which new educational spaces can be formed, contested and colonised beyond the classroom.

Introduction

In our recent systematic review of forest school literature in England (Garden and Downes Citation2021), we proposed a focus on space in future research to generate new complexities around the broader concepts that allow us to explore hybrid spaces constituted by both classrooms and Forest Schools. This means an examination of the various interactions between children, adults and artefacts that come together to generate existing and new spaces. By comparing, for example, classrooms with Forest Schools as constructed places, we proposed that it is possible to identify continuity and distinctiveness. Such an approach would open the possibility of Forest School interactions existing within classroom spaces as well as vice versa. We argue that the essential quality of Forest Schools is their relatively ambiguous nature: they provide opportunities for children to negotiate their interactions using processes garnered from a range of experiences, including those encountered in formal education. As such, they can be brought back into formal learning environments in ways that benefit those environments and thus become fundamental, rather than peripheral to shifts in formal practices (Garden and Downes Citation2021).

Additionally, we argue that such spaces create conditions in which new interactions, rituals and practices can be constructed. Forest School programmes lead to different learning experiences and outcomes and the construction of qualitatively different kinds of knowledge to those offered by more formal learning spaces. The tension between classroom spaces and outdoor spaces is something to be celebrated, rather than avoided. We argue that Forest Schools occupy a ‘third space’ (Bhabha Citation2012), existing between the highly ritualised spaces that constitute classrooms and the more fluid, flexible spaces that are present in home life. Forest Schools are new spaces where existing roles are subverted, and familiar actors are required to construct new identities and practices. We argue that this has the potential to create new opportunities for the construction of knowledge, not only within Forest Schools but beyond them.

There is an increasing interest in outdoor education and especially in Forest School (Forest School Association (FSA) Citation2021). Building on a rich history of outdoor learning, Forest Schools represent a distinctive educational approach that has emerged in the UK over the past 17 years (McCree and Cree Citation2017). Forest Schools originated from the Danish concept of ‘udeskole’ meaning ‘outdoor school’, which can be seen in many schools across Scandinavia (Knight Citation2013). This approach purports to develop the confidence of participants through opportunities to engage in learning experiences in a woodland environment (Murray and O’Brien Citation2005; Forest Education Initiative Citation2006). In these contexts, the outdoor environment is a significant and recognised aspect of the school curriculum. For example, Danish schools emphasise learning in outdoor contexts through curriculum subjects such as nature and technology (Danish Learning Portal Citation2018). Whilst UK curricula also reference outdoor spaces, their value is not explicitly highlighted in the same way leading to something of a lacuna in the validation of UK Forest Schools because they cannot be recontextualised in a way that is compatible with the original concept. UK Forest Schools often conflict with official discourses of knowledge and learning in a way that Scandinavian approaches do not. There is often no immediate connection in the UK between the outdoor space and existing curricular content; Forest Schools’ relationship with natural environments has a narrow overlap with formal learning requirements (Leather Citation2018).

This paper contributes to the growing body of literature around the use of outdoor spaces and in particular Forest School; a regular and repeated form of outdoor learning (Harris Citation2017). It focusses on the construction of Forest School space for outdoor educators (Garden Citation2022a) and provides a starting point for understanding the value of Forest Schools within outdoor education. A reduction in interaction with nature coincides with a growing sense of urgency concerning global environmental problems such as climate change and biodiversity decline (Harris Citation2021). Significant groups of children spend little time outdoors in natural environments (Hunt, Burt, and Stewart Citation2015). An engagement with the natural world is important if children are to develop an awareness of environmental issues (Zylstra et al. Citation2014; Beery and Wolf-Watz Citation2014). It is a concern that if children do not experience nature, they may not appreciate its potential value and therefore may not be concerned about its potential loss (Harris Citation2021).

The UK Forest School approach goes beyond learning outside the classroom as it creates a unique space to foster relational and meaning-making opportunities within the natural environment. These opportunities lead directly into the pathways to nature connectedness supporting potential health, wellbeing, and pro-environmental outcomes too (Harris Citation2017). This paper begins with positing the case for space, the positioning of childhood outdoors, building on our previous work on Forest School space (Garden and Downes Citation2021), discusses the background to Forest School in the UK and the implications and challenges for practitioners and teachers.

Forest schools in UK

The practice of using the outdoors as an educational tool has evolved internationally. Bertelsen’s junk playground in the 1940s, and Flatau’s ‘vandrebørnehave’ or ‘wandering kindergarten’ in the 1950s developed into what is known today as ‘skovbørnehave’ meaning ‘forest kindergarten’ (Williams-Siegfredsen Citation2017). Outdoor learning has been particularly significant in Scandinavian education and Scandinavian models of outdoor learning have influenced UK outdoor education discourses (Bentsen, Diabetes, and Ejbye-Ernst Citation2009). Whilst the notion of formal education happening in outdoor spaces can be seen as part of wider international discourses, Scandinavian approaches to outdoor education have taken on a distinct approach, largely due to cultural tendencies that foreground outdoor activities, such as ‘friluftsliv’ (fresh-air life) in Norway (Henderson and Vikander Citation2007). There is also the tradition of ‘forest pedagogy’, the progenitor of which was the Skogsmulle school and the ensuing ‘In Rain and Shine’ early years’ movement in Sweden. Similar initiatives evolved across Scandinavia, such as Metsamoori in Finland and åbørns pædagogik in Denmark (Cree and McCree Citation2012). These initiatives were characterised by a strong connection with the natural environment, which resonates with historical discourses that underpin outdoor learning initiatives developed in the UK.

Forest School in the UK emerged from Danish influences incorporating learning outside the classroom referred to as udeskole (meaning outdoors). The Scandinavian approach to early years’ education has a strong focus on the importance of ‘place’ for learning. Whilst initially it was created for early childhood education, the concept has expanded to include older age groups and children who have additional needs. Forest School ethos and practice aim to be nourished within social movements such as natural play, woodland culture, land rights and child-centred learning (Cree and McCree Citation2012). The experiential and progressive ideology and outdoor focus of Forest School education resonates with many of the concerns concerning childhood and the impact of the curriculum reforms introduced by the English Foundation Stage (DfES Citation2006).

Scandinavian approaches to Forest School allow the children to lead the learning as, according to Biesta, Allan, and Edwards (Citation2013), this encourages greater engagement from the children and richer learning opportunities. In England, however, the focus is on meeting children’s needs that align with the curriculum, creating tensions between sessions being child-led or structured by the teacher. Forest School practitioners often view the aims of sessions to be encouraging holistic development, but they often struggle with the concept of taking a step back and observing, compared to their usual pedagogy of adult-directed teaching (Garden Citation2022b). The culture within Forest School is increasingly becoming commodified and as a result, this is reducing the potential of Forest Schools. Within the UK, despite the rapid growth of Forest Schools, there are concerns that understanding is often not genuine, thus illustrating that undertaking Forest School training does not necessarily mean the development of deep and reflexive practice. Many researchers aim to uncover what makes Forest Schools unique compared to other learning experiences (Leather Citation2018).

Children in Denmark who take part in outdoor learning usually begin with an existing understanding and care for the environment due to friluftsliv (the Nordic concept of getting outdoors and into ‘free air’) culture (Williams-Siegfredsen Citation2017). The lack of widespread friluftsliv practice in the UK makes it more difficult for an approach such as Forest School to be a part of the mainstream educational experience; it is therefore perceived as ‘alternative’. Adapting friluftsliv in the UK causes it to lose its original meaning, therefore limiting the perceived benefits that children can gain from Forest Schools (Leather Citation2018).

In 2006, a Learning Outside the Classroom manifesto was launched by the government, followed by the formation of a Council for Learning Outside the Classroom in 2008, to assume responsibility for leading the roll-out of this manifesto (Council for Learning Outside the Classroom Citation2020). In addition, the provision of outdoor learning within the early years foundation stage became mandatory in 2007 (Department for Education and Skills Citation2006). Successive governments have acknowledged the importance of the early years, particularly with reference to social and economic outcomes. The legislation is applied in practice through a Foundation Stage in England. This runs from 0-5 years, with most children starting school at age 4 and beginning to study national curriculum subjects at 5–6 years of age in Key Stage 1. National Curriculum subjects demarcate a shift in children’s experience of education, from learning through play to more teacher-directed and content-determined learning. This usually means a move from more active to passive learning modes (Waite, Rogers, and Evans Citation2013) although outdoor learning, or engagement in Forest Schools to some extent offsets this change. However, as Waite (Citation2010) points out, at age 7 children move to Key Stage 2 and the opportunities for outdoor learning sharply decrease.

‘Policy borrowing’ in Forest School with the application of policy decisions in education in different contexts (Burdett and O’Donnell Citation2016, 133), the subsequent collectivisation of Forest School activities (Cree and McCree Citation2012) and the various government policy interventions (Council for Learning Outside the Classroom Citation2020) have given UK Forest Schools their distinctiveness. Firstly, the establishment of core principles widened the scope of activities to include all those in education (as opposed to restricting Forest Schools to pre-school provision). Secondly, Forest Schools were defined in a way that did not connect them to established education curricula other than in early years. Thirdly, the requirement of a level 3 qualification for all Forest School leaders fixed the characteristics of the activities within the environment. Finally, Department for Education and Skills (DfES) documentation, which focused solely on early years provision, created tensions with wider Forest School definitions.

The case for space

Forest School space can be argued to be the product of interrelations with multiplicity and space as co-constitutive (Massey Citation1995); that is, each has casual powers over the other. Space, therefore, is always under construction. A co-constructive understanding acknowledges a relational dynamic between the children, culture, risk, and the Forest School space that they inhabit and help to shape (Garden Citation2022a). For this reason, we have focused on Forest Schools as distinctive spaces that sit within, and interact with, other connected spaces.

Spaces are also bounded and are thus closed environments. We argue that human interactions that occur within spaces are not infinite. Within such environments, social structures form and limit the possibilities for human interaction. Boundaries create a distinction between what is and what is not, between the inside and the outside. As such, they can be material (walls, fences) but also semiotic (a Forest School can end at a given tree) and ritualistic (in this space we do these things). Such boundaries are created through social agreement (social practices) and become the foundations of further practices. Similarly, Laaksoharju and Rappe (Citation2017) highlight that trees provided many ways for children to become connected to place.

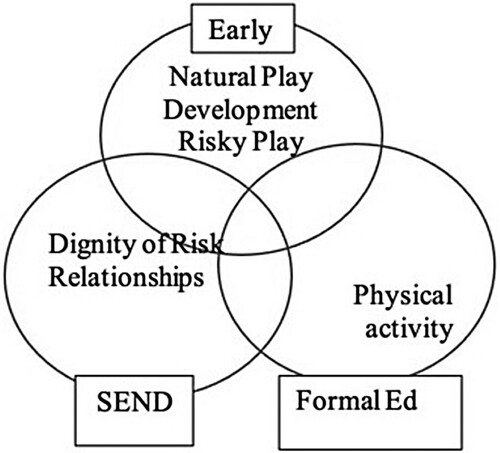

Our systematic literature review of forest school literature in England (Garden and Downes Citation2021) conceptualised the forest school space in the areas of early years, special education needs and disability, and formal education as presented in below:

Figure 1. Garden and Downes (Citation2021) space within forest school.

The contexts and themes on space identified within the literature on Forest Schools are historical (Garden and Downes Citation2021). For example, early years education has developed outdoor learning as a focus for practice, particularly concerning the importance of outdoor play to early child development (Davies Citation2018). Similarly, a body of historical work has concentrated on the importance of outdoor learning for children with special educational needs and disabilities because of the opportunities such contexts provide for children to experience risk (Perske Citation1972). This interaction between context and themes are important because such relationships are not necessarily transferable. For example, what is desirable in early years settings might not be desirable in other educational settings. Broader theorisations of outdoor learning, specifically those associated with space, are more rarely utilised in the literature, with only three articles referring to these concepts in any sustained fashion (Garden and Downes Citation2021) (see Cumming and Nash Citation2015; Harris Citation2018; Mycock Citation2019). We (Garden and Downes Citation2021) posit that this is an area that requires more specific attention for those writing about Forest Schools because more abstract theorisations, such as spatialisation, provide opportunities for a broader, more distributed discussion that is not constrained by historical discourses associated with given contexts (Foucault Citation1972).

A redefinition of the relationship between space and time in Forest Schools creates a more dynamic account of reality. Rather than a timeless, closed system, space becomes a ‘discrete multiplicity (that is) imbued with temporality’ (Massey Citation2005, 55). According to Massey, there is confusion between time and space, which emanates from a sense that both are facets that exist independently of us. Such an approach ignores the work of Kant, which is central to most modern paradigms of thought. For Kant, time and space are a priori functions, that is, they form the architecture by which we make sense of the world: we see objects in space but only make sense of them through difference, as they change through time (Massey Citation2005, 57). In other words, both time and space are internal concepts that form the basic architecture of cognition. For Massey, this understanding necessarily requires an ontological reframing. Rather than a dualism between our experiences of an external world, predicated on matter, and our internalised thoughts, predicated on time, the world is a range of narratives that play out as we move through space and time.

The multiplicity of possibilities afforded by Massey’s approach are effectively illustrated by the distinction between ‘space’ and ‘place’, where ‘place’ is the positioning of static objects such as those in nature in Forest Schools and ‘space’ is the multiple interactions that occur between such objects (Agnew Citation2011). Whereas the former provides no possibility for diverse outcomes and agency, the latter provides for multiple trajectories to exist within the same context. Furthermore, an individual can operate multiple trajectories through the same space.

The ‘third space’, as initially conceptualised by Bhabha, tacitly acknowledges the interconnectedness of different spaces (Potter and McDougall Citation2017). Thus, a Forest School exists as a place (e.g. trees, paths, fire circle) but one that is continually being recreated and is always subject to the possibility of change. As a space, it contains actors that progress on multiple trajectories (rangers, teachers, pupils) including those that exist pluralistically (a teacher can also be a ranger).

The value of the outdoor space

According to Coates & Pimlott-Wilson (Citation2019), children’s increased use of digital technology has played a crucial role in a decline in their engagement with outdoor activities. Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic, which affected the UK from March 2020, contributed to children staying indoors and restricting contact with their peers. It is often argued that the decrease in outdoor activity is, in part, due to a concomitant increase in young people’s exposure to digital technologies (Garden Citation2022b). However, little is understood about the potential of such technologies to enhance outdoor spaces. Often technology and outdoor activities are viewed as existing within an ‘either/or’ relationship, but this may well be a false dichotomy (Garden Citation2022b). It has been argued that children’s engagement with nature and the outdoor environment has been compromised by digital technology which provides a quicker, easier, and less demanding form of interaction and intellectual development (Louv Citation2005).

The anti-modern representation of an idyllic and, invariably, rural childhood manifests itself in the highly influential work of Richard Louv, whose Last Child in the Woods (2010) has been celebrated by organisations such as the National Trust (Moss Citation2018) which endorse Louv’s ‘diagnosis’ that children are suffering from ‘Nature Deficit Disorder’. Both Moss and Louv recognise that this is not a medical condition; the use of the term has become commonplace because it resonates with a more general pathologisation of children, characterised by the contested psychological condition Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Louv (Citation2005) suggests that, to remain healthy, children do not just need good nutrition and adequate sleep, but also need contact with nature.

Palmer’s highly influential Toxic Childhood (2006) and Detoxifying Childhood (2007) considers the impact of the ‘denial’ of play, in particular outdoor play. Palmer argues that, because of technological advancement and a reduction in traditional forms of play, combined with exposure to consumerist messages, children’s emotional, social, and cognitive development is being compromised. He suggests that the antidote is nature and therefore a move away from technology. Palmer proposes that children’s lives should be ‘free range’, rather than the sedentary, technologically mediated, nature-deprived ‘battery’ living they now experience.

As an antidote to both technological over-exposure and over-protection, there have been moves amongst parents, campaigners, policy advisors, the DfES (Citation2006) and advocates, such as Wild Nature, Playing Out and Project Wild Thing, to reintroduce risk-taking behaviours into the lives of children. In doing so, they aim to counter both the perceived cocooning of children and the pervasive negative understanding of risk, which is seen to emasculate not only children but parents and those who, while acting in loco parentis, are responsible for children’s welfare and wellbeing. An educational initiative that has been offered as an exemplar (DfES Citation2006) in countering such ubiquitous risk aversion is a policy borrowed from Scandinavia-Forest School education. Proponents of this initiative argue that through exposing children to both nature and risk (Knight Citation2013, Forest School education can mitigate some of the perceived deleterious impact that contemporary hyper-risk aversion can have on children’s wellbeing. The ‘safe’ space of Forest School allow risk to be explored and children to assess the levels of risk for themselves (Garden Citation2022a).

The work of Goffman may help to elucidate how social groups legitimise their existence and colonise social spaces (Goffman Citation1971). For Goffman, it is not possible to talk about an individual as a single, immutable entity; to do so is to miss the pluralistic nature of a person’s interactions with the world, preferring instead to use the term ‘unit’ to refer the different ways in which individuals and groups of people can ‘be’ in the world (Goffman Citation1971, 3–27). Thus, a person is comprised of many different units depending on the context of their interactions. Furthermore, an individual might not act alone as a single unit; a unit can also refer to an orderly group, which acts as one (a unit with).

Goffman (Citation1971) makes the significant point that all goods themselves are bounded: that is, everything we value has distinct edges; the point at which something stops being valued is the boundary. For example, children digging with sticks creates all sorts of value-driven activity: the territory where the digging is taking place, objects produced by digging, and ‘buried treasure’. For Goffman, social goods are themselves territories, which units make claims against. Of course, in making such claims, units extend and shape the nature of the territory they are colonising. This linking of space (territory) and goods (value) provides insights into the way spaces are formed and the social orders that run through them.

Through connecting with nature and the natural world, we argue that children develop a sense of belonging and responsibility towards the wider environment supporting the development of pro-environmental attitudes. Harris (Citation2021) believes that it is development of ties with places along with positive experiences in the space that will encourage the development of pro-environmental behaviour in children and a desire for protection of that environment. Similarly, Kudryavtsev, Stedman, and Krasny (Citation2012) in their review argue that people will want to protect places that are meaningful to them within cultural, social, and ecological perspectives. Forest School is a different ‘cultural’ space where children and young people, as well as practitioners, have relative autonomy in activities away from the confines of the more ‘structured’ formal school setting (Harris Citation2017).

In considering outdoor space, the less predictable nature of the Forest School space may make the outdoor space more dynamic than an approved play space such as a playground; a space that is often designed to prevent injury (Garden Citation2022a). The idea of ‘risky play’ in the Forest School space can be described as play fitting within the category of physical play and is described as active, exciting, and having elements of risk (Kleppe, Melhuish, and Sandseter Citation2017). Risky play can be argued to be a necessary component of healthy child development and the promotion of physical, social, and mental health in children. Opportunities though to experience nature first-hand are increasingly rare for many children, especially those who live in urban areas, without gardens, and with limited opportunity for free play outdoors (Harris Citation2021). Forest Schools can be viewed as distinctive spaces that sit within, and interact with, other connected spaces. Harris (Citation2021) found that fostering a relationship with nature and place and the development of pro-environmental behaviour in the longer term is a fundamental part of the practice for forest school practitioners. Forest schools are generally viewed as an alternative pedagogy and a space as free from the constraints of the national curriculum.

Forest School can be seen as offering an alternative learning environment from which curricular links can be made, particularly with respect to science, maths and the arts (Cumming and Nash Citation2015). As well as offering a different context for learning, the learning approach associated with Forest School is understood as being quite different from that of mainstream school, that is, constructivist rather than instructional, and an alternative way of delivering the curriculum, which can be embedded into the schools’ education framework as a whole (Cumming and Nash Citation2015). This, it is argued, can support children’s motivation to learn and so Forest School is often positioned as complementing or supplementing classroom learning, a form of curriculum enrichment that allows children to develop key skills such as problem-solving (Slade, Lowery, and Bland Citation2013). It is Forest School’s unique purpose that seems to distinguish it from other types of outdoor learning. Forest School increases children’s connections with nature within the cultural and social context of an ever-urbanised and indoor society; it also aims to increase young children’s motivation to learn (Waite, Bølling, and Bentsen Citation2016), mainly by stimulating their interests.

Forest School is a vehicle for the curriculum and not a curriculum in itself. Tensions can exist when the curricular goals and philosophy do not fully align with its ethos. As Mycock (Citation2019) argues, Forest School pedagogy is often a mix of contradictory influences, including experiential learning; play-based learning; child development theories; environmental science; and ‘nature’ studies. An ‘ideal representation’ of Forest School and what it entails can be quite different from reality. For example, Forest School education has been endorsed because it explicitly encourages ‘risky’ activities such as fire lighting, knife use and tree climbing, activities from which children are increasingly prohibited. As a result of these attitudinal and policy changes, as well as the increased competition between schools in the United Kingdom wishing to distinguish themselves through the Forest School badge, there has been a precipitous increase in the number of both private and school-based Forest Schools. With many providers claiming to offer Forest School education, and to standardise this increasingly fragmented ‘market’ the Forest School Association was formed in 2012.

Forest as undecided spaces

It is possible to consider space in a more contextualised way by considering the behaviours that are expected from all parties in Forest Schools – the children, teachers, and Forest School leaders – and the relative ways in which they negotiate their respective roles within the space. We propose that these labels are contingent upon the spaces in which they exist. Therefore, the label of ‘teacher’ is dependent on the classroom context to determine the various practices associated with the role. When people with roles defined in a different context are brought into the Forest School space, their roles become more fluid and negotiable. Forest Schools are thus in many ways an undecided space where new roles are formed, and old roles are renegotiated. Harris (Citation2017), for example, found that the outdoor learning space of Forest School allows teachers and pupils to deviate from the norms and conventions of the classroom, which in turn leads to them adopting different learning attitudes and engage in more child-led learning. Similarly, Ridgers, Knowles, and Sayers (Citation2012) reported the positive influence that Forest School had on children’s natural play and their knowledge of the natural world. It is important that outdoor learning in nature is recognised as fostering pro-environmental behaviour (Öhman and Sandell Citation2016).

Tensions between teachers and Forest School leaders can arise when discussions have not taken place around how differing principles can support the purpose of the session, leading to misunderstandings about who is responsible for behaviour and learning. This tension is further exacerbated by a more risk-averse UK context, meaning that teachers are more likely to pass responsibility to external ‘expert’ providers whilst often ultimately remaining responsible for their pupils. Discourses of risk are one of the most central issues in the wider contestation of Forest Schools. For example, the use of knives as tools for construction can be questioned by teachers, headteachers, parents and even those more widely responsible for running Forest Schools. This can lead to differing expectations of behaviour when using knives and the extent to which such activities are controlled.

Peacock and Pratt (Citation2011) similarly describe a ‘cultural border’, present in subtle changes in the relationship between staff and children when outdoors. This cultural border is created by differing goals for learning when outdoors, combined with a different approach to pupil expectations for behaviour. The approaches to teaching are therefore subtly altered (Harris Citation2017). However, an important subtlety is that children within a Forest School ethos are testing their boundaries and therefore positively challenging themselves, as opposed to challenging authority (Moss Citation2019).

We suggest that the tensions created between classroom roles and Forest School practices necessitate the need for a symbolic ‘gateway’ between the classroom and Forest Schools. In many Forest Schools, this is represented by the fire circle which acts as the initial meeting place and the focal point for discussions, instructions and community eating. At each of these points, the Forest School begins or ends as a constructed space and familiar roles that reference classroom practices are re-established. Thus, there is a constant link between the classroom and Forest Schools. Forest Schools and classrooms act in tension but are inter-connected. Vygotsky (Citation1978) similarly believed that learning and knowledge should be shared between individuals and that education should focus on the learning process and not the performance.

The concept of place attachment (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010) and the bonding of people to places has been investigated in more detail to reveal debates about whether it relates to a specific place, or a type of place such as a specific wood, or woods in general (Harrington Citation2018). Place attachment is the bonding through social ties and activities, of individuals and the environment that affords meaning for them (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010). We can also consider the nature of that relationship such as whether it is based on the restorative aspects of a place, a commitment to return to the place, ecological stewardship, habit and familiarity, a refuge from daily routine, a place to relax or a place to belong (Harris Citation2021). There is a need for a greater recognition of the need to understand the processes through which attachment to places occur (Morgan Citation2010; Lewicka Citation2011). A key role in development of a sense of place and place attachment is the physical and social development that Forest School affords participants (Beames and Ross Citation2010) as participants begin to see themselves in relation to all the other creatures within that setting.

We argue that there is a need to understand the processes through which people go through in terms of establishing meaningful relationships with places whether it be pivotal moments or feelings of safety in a place. Similarly Raymond, Brown, and Weber (Citation2010) identify the role of a physical setting in creating a specific venue for social experiences, and the subsequent social bonds and relationships with others, or with a specific place that form. The greater exposure to the natural environment the more it affords meaning to them, promoting a sense of belonging. We suggest that a model of place attachments should be related to natural aspects of a place in terms of the impact on environmental identity, whereas emotional attachment to places relates to pro-environmental behaviours (Harris Citation2021).

Conclusion

We argue that a tacit acknowledgement of Forest Schools as distinctive spaces allows for the concomitant generation of new ways of describing Forest Schools and their value to those who engage with them. Such notions of new spaces as distinctive of, but complementary to, existing educational spaces are not new. The emergence of digital technologies has necessitated a similar approach when considering their affordances within the education context (Potter and McDougall Citation2017). A ‘third space’ (Potter and McDougall Citation2017, 37) may describe the interconnectedness of different spaces for learning across various domains. Whilst spaces can exist antagonistically with one another, usually defined by rigid impenetrable borders, many exist in affiliation (Bhabha Citation2012). A space does not become a place until we interact and socialise within it.

We argue that the ‘gateway’ into Forest School is an important moment of transition from one place (usually a school) to another. In Forest Schools, this gateway is usually symbolised using a fire circle. This is where the context for the Forest School space is created through establishing who will say what and when, who will have control over what, and general rules about how to move around and interact with the space. The continuity with connected spaces (e.g. the classroom) can therefore be established. The more the gateway references classroom rules, practices, and roles, the greater the continuity; the fewer references there are, the more discrete the space becomes. We argue that the ideal is a blend of both; a connection with other spaces so that Forest Schools become meaningful in these contexts, and disconnection, leading to Forest Schools becoming distinctive spaces.

It should be emphasised that boundaries, gateways, and general rules do not constitute a space. Even within the more rigid boundaries of a classroom, there is room for other types of knowledge construction to occur (e.g. Kelly Citation2010). As the existing foliage that forms rigid structures within a Forest School environment generates constraints and possibilities for new botanic growth, so the boundaries of the Forest School generate constraints and opportunities for new social interactions. As with connected spaces like schools, these social interactions need their expression of value to lay moral claim to their existence in relation to other spaces (Rawls Citation2010). The existing notions of the value of digital spaces as learning spaces provide points of reference.

Such discourses tend to foreground creativity and collaboration (Craft Citation2005). We suggest that this should be the starting point for understanding the value of Forest Schools. For example, Manner, Doi, and Laird (Citation2020) in their research with adolescent girls with mental health issues, reported that their mood, confidence, social skills and relationships, were all positively affected as a result of taking part in the Forest School programme and that the impact extended beyond the Forest School setting. Often such approaches are placed in opposition to the instrumental paradigms that are seen to characterise formal education (Biesta, Allan, and Edwards Citation2013; Potter and McDougall Citation2017). We argue that it is not necessarily the case: less rigid forms of knowledge construction can be measured against frameworks that express desirable outcomes (e.g. Gunawardena, Lowe, and Anderson Citation1997; Wallas Citation2018). This provides a point of connection with the more rigid, state-sponsored discourses of formal education. We see this as a potential opportunity to subvert these discourses in a way that provides opportunities for growth in recognition of the value of Forest Schools. In the words of Heidegger, ‘A boundary is not that at which something stops but, as the Greeks recognised, the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing’ (Heidegger Citation1971, 152).

This article has built on our previous paper (Garden and Downes Citation2021), which identified a set of abstract themes emerging from our work on space. Whilst all of these relate to outdoor learning, they represent three distinct contexts: early years, special education needs and disability, and formal education. We posited that this is an area that requires more specific attention for those writing about Forest Schools because more abstract theorisations, such as spatialisation, provide opportunities for a broader, more distributed discussion that is not constrained by historical discourses associated with given contexts (Foucault Citation1972). The focus on certain educational contexts is particularly significant because accepted practices within a given setting affect what is perceived as possible and therefore fixes the scope of the theoretical lens through which activities are interpreted (Garden and Downes Citation2021).

Consideration of the physical space can mean there is a need to redefine how we conceptualise the notion of space within Forest Schools. Space is how individuals view the extension of learning beyond the confines of the classroom, not just the physical space (Garden Citation2022a). The idea of Forest School as a range of narratives for children played out in time and space links into Massey’s ideas and this understanding necessarily requires a redefinition of the ontological question. Rather than a dualism between our experiences of an external world, predicated on matter, and our internalised thoughts, predicated on time with both having their own characteristics. This redefinition of the relationship between space and time in Forest Schools necessarily creates a more dynamic account of the real. Rather than a timeless, closed system, space becomes a ‘discrete multiplicity (that is) imbued with temporality’ (Massey Citation2005, 55).

Building on our ‘Space within Forest School’ conceptual framework (Garden and Downes Citation2021) we argue that UK Forest Schools should be seen as third spaces (Bhabha Citation2012) between the familiar contexts of school and home. Each of these environments has its own established rituals and practices (teacher, parent, pupil, child). Forest Schools are inextricably linked to these contexts but are also distinctive. This means that the connection needs to be defined through gateways to the environment where external practices are acknowledged. We believe that such a model provides scope for interaction between home, school, and Forest School. This paper contributes to knowledge in the field of outdoor education research by presenting Forest Schools as a ‘third space’ providing opportunities for participants to develop in previously unacknowledged ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agnew, J. 2011. “Space and Place.” In The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, edited by J. Agnew, and D. Livingstone, Chap. 23, 316–330. London: Sage.

- Beames, S., and H. Ross. 2010. “Journeys Outside the Classroom.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 10 (2): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2010.505708.

- Beery, T. H., and D. Wolf-Watz. 2014. “Nature to Place: Rethinking the Environmental Connectedness Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 40: 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.06.006.

- Bentsen, P., S. Diabetes, and N. Ejbye-Ernst. 2009. Friluftsliv. https://udeskole.nu/wp-content/uploads/77_1_Forskning-i-udeskole.pdf accessed 06/08/2021.

- Bhabha, H. K. 2012. The Location of Culture. Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Biesta, G., J. Allan, and R. Edwards. 2013. Making a Difference in Theory : The Theory Question in Education and the Education Question in Theory. London : Routledge.

- Burdett, N., and S. O’Donnell. 2016. “Lost in Translation? The Challenges of Educational Policy Borrowing.” Educational Research 58 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1080/00131881.2016.1168678.

- Coates, J. K., and H. Pimlott-Wilson. 2019. “Learning While Playing: Children’s Forest School Experiences in the UK.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1002/berj.3491.

- Council for Learning Outside the Classroom. 2020. History of Council for Learning Outside the Classroom. https://www.lotc.org.uk accessed 06/08/2021.

- Craft, A. 2005. Creativity in Schools: Tensions and Dilemmas. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Cree, J., and M. McCree. 2012. A brief history of the roots of forest school in the UK. Horizons, 60, 32–34. Retrieved from https://www.outdoor-learning-research.org/Portals/0/Research%20Documents/Horizons%20Archive/H60.History.of.FS.pt1.pdf?ver=2014-06-23-151226-000.

- Cumming, F., and M. Nash. 2015. “An Australian Perspective of a Forest School: Shaping a Sense of Place to Support Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. Routledge 15 (4): 296–309. doi: 10.1080/14729679.2015.1010071.

- Danish Learning Portal. 2018. Nature and technology. Retrieved from https://emu.dk/grundskole/naturteknologi acccessed 06/08/2021.

- Davies, R., et al. 2018. ‘Assessing Learning in the Early Years ‘ Outdoor Classroom : Examining Challenges in Practice Examining Challenges in Practice’, 4279. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2016.1194448.

- Department for Education and Skills. 2006. Learning outside the classroom: Manifesto. Retrieved from http://www.lotc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/G1.-LOtC-Manifesto.pdf.

- Forest Education Initative. 2006. Forest schools. https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/research/a-review-of-the-forest-education-initiative-in-britain/ accessed 06/08/2021.

- Forest School Association. 2021. https://forestschoolassociation.org.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge & the Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. Leek, UK: Colophon Books.

- Garden, A. 2022a. “The Case for Space in the co-Construction of Risk in UK Forest School.” Education 3-13 International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education 1–12. doi:10.1080/03004279.2022.2066148.

- Garden, A. 2022b. “An Exploration of Children’s Experiences of the use of Digital Technology in Forest Schools.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 1–15. doi:10.1080/14729679.2022.2111693.

- Garden, A., and G. Downes. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Forest Schools Literature in England.” Education 3-13 International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education. Published online 25 Aug 2021. doi:10.1080/03004279.2021.1971275.

- Goffman, E. 1971. Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Gunawardena, C. N., C. A. Lowe, and T. Anderson. 1997. “Analysis of a Global Online Debate and the Development of an Interaction Analysis Model for Examining Social Construction of Knowledge in Computer Conferencing.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 17 (4): 397–431. doi:10.2190/7MQV-X9UJ-C7Q3-NRAG.

- Harrington, L. M. B. 2018. “Alternative and Virtual Rurality: Agriculture and the Countryside as Embodied in American Imagination.” Geographical Review 108 (2): 250–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12245.

- Harris, F. 2017. “The Nature of Learning at Forest School: Practitioners’ Perspectives.” Education 3-13 45 (2): 272–291. doi:10.1080/03004279.2015.1078833.

- Harris, F. 2018. “Outdoor Learning Spaces: The Case of Forest School.” Area 50 (2): 222–231. doi: 10.1111/area.12360.

- Harris, F. 2021. “Developing a Relationship with Nature and Place: The Potential of Forest School.” Environmental Education Research 27 (8): 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1896679.

- Heidegger, M. 1971. Poetry, Language, Thought. (A. Hofstadter, Trans.). London, UK: HarperCollins.

- Henderson, B., and N. Vikander. 2007. Nature First: Outdoor Life the Friluftsliv way. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn.

- Hunt, A., J. Burt, and D. Stewart. 2015. Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: A Pilot for an Indicator of Visits to the Natural Environment by Children - Interim Findings from Year 1 (March 2013 to February 2014). Natural England Commissioned Reports, Number 166.

- Kelly, C. 2010. Hidden Worlds : Young Children Learning Literacy in Multicultural Contexts. Stoke: Stoke-on-Trent.

- Kelly, P. 2014. “Intercultural Comparative Research: Rethinking Insider and Outsider Perspectives.” Oxford Review of Education 40 (2): 246–265. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.900484.

- Kleppe, R., E. Melhuish, and E. B. H. Sandseter. 2017. “Identifying and Characterizing Risky Play in the Age One-to-Three Years.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (3): 370–385. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308163.

- Knight, S. 2013. International Perspectives on Forest School: Natural Spaces to Play and Learn. London, UK: SAGE.

- Kudryavtsev, A., R. C. Stedman, and M. E. Krasny. 2012. “Sense of Place in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 18 (2): 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.609615.

- Laaksoharju, T., and E. Rappe. 2017. “Trees as Affordances for Connectedness to Place – a Framework to Facilitate Children’s Relationship with Nature.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 28: 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.10.004.

- Leather, M. 2018. “A Critique of “Forest School” or Something Lost in Translation.” Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 21: 5–18. doi:10.1007/s42322-017-0006-1.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (3): 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001.

- Louv, R. 2005. 2010) Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder. London: Atlantic Books.

- Manner, J., L. Doi, and V. Laird. 2020. “‘That’s Given me a bit More Hope’ – Adolsecent Girls’ Experiences of Forest School.” Children’s Geographies 19 (4): 4332–445. doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1811955.

- Massey. 1995. Thinking Radical Democracy Spatially. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. First Published June 1, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1068/d130283

- Massey, D. B. 2005. For Space. London, UK: SAGE.

- McCree, M., and J. Cree. 2017. “Forest School: Core Principles in Changing Times.” In Children Learning Outside the Classroom – from Birth to Eleven, edited by S. Waite, 222–232. London: SAGE.

- Morgan, P. 2010. “Towards a Developmental Theory of Place Attachment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.07.001.

- Moss, P. 2018. Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. UK: Oxford.

- Moss, J.2019. Researching education: Visually – digitally - spatially [Brill]. doi:10.1163/9789087902339

- Murray, R., and E. O’Brien. 2005. Such enthusiasm – a joy to see: An evaluation of Forest School in England. UK: Report for the Forestry Commission.

- Mycock, K. 2019. “Forest Schools: Moving Towards an Alternative Pedagogical Response to the Anthropocene?” Discourse. Taylor & Francis 0 (0): 1–14. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2019.1670446.

- Öhman, J., and K. Sandell. 2016. “Environmental Concerns and Outdoor Studies.” In Routledge International Handbook of Outdoor Studies, edited by B. Humberstone, H. Prince, and K. A. Henderson, 30–39. London: Routledge.

- Peacock, A., and N. Pratt. 2011. “How Young People Respond to Learning Spaces Outside School: A Sociocultural Perspective.” Learning Environments Research 14: 11–24. doi:10.1007/s10984-011-9081-3.

- Perske, R. 1972. “The Dignity of Risk and the Mentally Retarded.” Mental Retardation 10 (1): 24–27. PMID: 5059995.

- Potter, J., and J. McDougall. 2017. Digital Media, Culture and Education: Theorising Third Space Literacies. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rawls, A. W. 2010. “Social Order as Moral Order.” In Handbook of the Sociology of Morality. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, edited by S. Hitlin, and S. Vaisey, 95–121. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6896-8_695–121.

- Raymond, C. M., G. Brown, and D. Weber. 2010. “The Measurement of Place Attachment: Personal, Community, and Environmental Connections.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (4): 422–434. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002.

- Ridgers, N. D., Z. R. Knowles, and J. Sayers. 2012. “Encouraging Play in the Natural Environment: A Child-Focused Case Study of Forest School.” Children’s Geographies 10 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1007/978-981-4585-90-3_2-1.

- Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. “Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006.

- Slade, M., C. Lowery, and K. Bland. 2013. “Evaluating the Impact of Forest Schools: A Collaboration Between a University and a Primary School.” Support for Learning 28 (2): 66–72. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12020.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Oxford, UK: Harvard University Press.

- Waite, S. 2010. “Losing our way? The Downward Path for Outdoor Learning for Children Aged 2-11 Years.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 10 (2): 111–126. doi:10.1080/14729679.2010.531087.

- Waite, S., M. Bølling, and P. Bentsen. 2016. “Comparing Apples and Pears?: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Forms of Outdoor Learning Through Comparison of English Forest Schools and Danish Udeskole.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 868–892. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1075193.

- Waite, S., S. Rogers, and J. Evans. 2013. “Freedom, Flow and Fairness: Exploring how Children Develop Socially at School Through Outdoor Play.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 13 (3): 255–276. doi:10.1080/14729679.2013.798590.

- Wallas, G. 2018. The Art of Thought. London, UK: Solis Press.

- Williams-Siegfredsen, J. 2017. Understanding the Danish Forest School Approach: Early Years Education in Practice. Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Zylstra, M. J., A. T. Knight, K. J. Esler, and L. L. Le Grange. 2014. “Connectedness as a Core Conservation Concern: An Interdisciplinary Review of Theory and a Call for Practice.” Springer Science Reviews 2 (1–2): 114–119. doi:10.1007/s40362-014-0021-3.