ABSTRACT

This research builds on a previous study which found that ‘fault lines of failure’ existed in the Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice 2015 (SENDCOP). The fault lines that were revealed, through a historical analysis of policy and practice, were those of multi-agency working, the training of professionals, pupil/ parent voice, and the funding of the systems of SEND. This current research, through the application of a thematic analysis, sought to examine whether the ‘fault lines’ evidenced in this previous research were observable in politician’s speeches detailed in Hansard from December 2014 to May 2022. The research found that similar to extant research the fault lines of failure were indeed observable and that there was also a significant disjunct between government rhetoric and that of parliamentarians as to the success of the operation of the SENDCOP. The research concludes that moving into a new legislative era, the government must not only listen to, but must hear and heed the voices of parliamentarians as these voices offer a source of wisdom and provide early warning to the opening of the ‘fault lines of failure’ which have doomed previous SEND policies to failure.

Introduction

Previous research has revealed ‘fault lines of failure’ at the core of all iterations of the government's legislative frameworks of SEND since the 1980s (Hodkinson Citation2023). This research argued such ‘fault-lines’ served as structural impediments to the current SENDCOPs efficient and effective implementation and operation. The fault lines revealed in the previous research were those of multi-agency working, pupil/ parent and professional partnerships, funding, and teacher training.

This current study builds on the conclusions of the existing research which demonstrated how the government was bombarded with criticism and recommendations, from 1978 onwards, in relation to its inception and operation of its systems of SEND in England. Indeed, the previous research indicated that the 1981, 1993, 2001, and most recently the 2014 Act, and their SENDCOPs, failed to adequately support children. This research concluded that despite significant government rhetoric to the contrary, forty years of legislation had not inculcated a radical cultural change in practice but had led only to systems of SEND that were under-resourced and ‘harmful for children and all those involved’ (Ahad, Thompson, and Hall Citation2022, 20). It detailed that legislation had created ‘warrior parents’ (Lamb Citation2019) who had to ‘swear and make a stink’ (Cullen and Lindsay Citation2019, 3) as they battled the system to ensure that their children were supported.

The current study aims to demonstrate that the fault-lines identified in the previous research are also evident in the speeches of parliamentarians, as evidenced in Harvard between December 2014 to May 2022. In addition, this research aims to evidence that there was a clear divide between government rhetoric and the voices of parliamentarians, of all political parties, as to the success of the systems of SEND management introduced it introduced in 2014.

Firstly, some contextual historical detail, as to the causation of the 2014 SEND systems failure, is provided beginning with the fault line of multi-agency working.

Examining multi-agency working, parents/ pupils, participation, and partnerships

Section 25 of the Children and Families Act (CFA) (Citation2014) places a legal duty on local authorities (LAs) to guarantee that education, training, and social care provision:

‘ensure[s] that services consistently place children and young people at the centre of decision-making and support … challenging any dogma, delay or professional interests that might hold them back’.

Within SEND, Watson et al. (Citation2002) suggest multi-agency working necessitates the bringing together of a range of professionals across the boundaries of education, health, social-care, welfare, voluntary organisations, parents and pupils, and their advocates, all with the purpose of working towards holistic approaches to access high-quality services for children. There can be no doubt though that multi-agency working is complex and fraught with difficulties, not least because of the plethora of services involved. As example, the Children and Families Act (Citation2014) details the types of services that might be involved in joint commissioning arrangements:

‘Specialist support and therapies, such as clinical treatments and delivery of medications, speech and language therapy, assistive technology, personal care (or access to it), Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) support, occupational therapy, rehabilitation training, physiotherapy, a range of nursing support, specialist equipment, wheelchairs and continence supplies and also emergency provision … ’.

(Children and Families Act Citation2014, 40)

Multi-Agency working: what can go wrong?

Within multi-agency working, confusion can arise because of the plethora of language that is employed to describe how various agencies and services work together to support children (Hussain and Brownhill Citation2014). As an example, multi-agency working itself can be described in many differing and divergent ways. Such as:

Integrated working

Multi-agency/ Cross-agency/ Interagency/ Trans-agency

Co-ordination

Co-operation

Collaboration

Partnerships

‘Joined up thinking’ and ‘joined up working’

Cross cutting

Network

Working together

Interprofessional working (Kaehne Citation2014; Payler and Georgeson Citation2013; Stone and Foley Citation2014)

Universal Services – where all children can access without a special referral. For example, GPs, dentists, opticians, nurseries, schools, colleges, and hospitals.

Targeted Services – These services provide support for certain groups of children. Such services might include children’s centres, parental support, and social services.

Specialist Services – required when universal services are unable to meet the individual needs of a child. These services might include family support workers, behaviour support workers, speech and language therapists, physiotherapists, youth offending teams, dietitians, and child and adolescent mental health workers. (Hussain and Brownhill Citation2014)

Research by the Care Co-ordination Network UK (Citation2004) has shown that, on average, families of children labelled with SEND have contact with at least ten different professionals over the course of the year and can attend up to 20 appointments at hospitals and clinics. It is vital, therefore, that professionals work together through a multi-agency approach to support children and their families (Atkinson et al. Citation2002). The literature base, though, also identifies several challenges that serve to undermine the effectiveness of multi-agency partnerships (see Atkinson et al. Citation2002). These challenges normally centre around four broad areas. These being:

funding and resources: one of the major challenges involved with the development of multi-agency partnerships is the simple question, ‘Who is going to pay for these initiatives?’

roles and responsibilities: within any partnership arrangement a fundamental question is ‘Who should lead the multi-agency team?’ Whose procedures and practices should dominate the approach taken with an individual child and their family?

competing priorities: each service provider in a multi-agency team may be held responsible by different government departments or indeed have different inspection regimes that they are accountable to. The question that can dominate multi-agency teams is ‘Who is accountable when something goes wrong?’

communication: one of the major reasons for developing multi-agency partnerships was in response to the death of Marie Coldwell and the lack of communication between professionals that was a contributory factor in this case.

The key success factors involved in multi-agency working

According to the NFER (Atkinson et al. Citation2002) successful multi-agency working is based upon effective systems and practices that ensure good communication, adequate resources in terms of staffing and time but more importantly that the professionals involved have the commitment and drive to ensure that this form of provision works in practice. In addition, another key success factor is that all agencies understand their own roles and responsibilities as well as those of other agencies and that multi-agency teams are led by people with vision and tenacity (Hodkinson Citation2019a). Thus, as Warnock indicated, what is crucial to effective multi-agency partnership working is the ability of various professional disciplinary areas to be able to train together, share ideas and resources and to work more co-operatively across professional boundaries (Department for Education and Science (DES) Citation1978; Jahans and Bayton Citation2022). In attempting to address these areas the government in 2014 set out to establish much more responsive services with timely support for children and their families. However, previous research (Hodkinson Citation2023) details that such aspirations were not realised.

Training and SEND: a missed opportunity?

Turning now to provide some contextual detail as to the second fault-line that of teacher training in relation to the systems and practice of SEND. It seems clear that training for the teaching of pupils labelled with SEND has been an issue that has inhibited the successful implementation of legislative frameworks in the past (Hodkinson Citation2019b). Indeed, as early as 1978, Warnock (DES Citation1978) recognised that a lack of training acted as a barrier to the integration of pupils in mainstream schools. Warnock’s report into SEND at that time concluded that increasing the knowledge base of teachers was of the ‘upmost importance’ (DES Citation1978, 121). This Report advocated that teachers should be able to recognise the early signs of SEN. The Report further stated that students should understand,

developmental difficulties;

the steps necessary for meeting a child’s need;

the attitudes needed for dealing with SEN; and,

how to modify classrooms and the curriculum.

‘Some 40 years will need to elapse … before it can be assured that all teachers have undertaken … such initial training (DES Citation1978, 244).

In 2007, the teacher development agency (TDA) again warned about the issue of training stating that, ‘by improving [trainees] knowledge and skills we can help them deliver a more inclusive … learning experience for pupils’ (TDA Citation2008, 1). Despite some new training modules, nothing though really changed in how teachers were prepared to teach SEND (Basingstoke Citation2008). It was at this time that SENDCOP 2015 was introduced. Whilst many broadly welcomed the new code (Hodkinson Citation2019a) the timescale for its implementation was regarded with unease by parliamentarians. This was because the Bill’s passage through parliament left only a few months before schools had to implement SENDCOP leaving no time to provide workforce training (Perry Citation2014). The Carter Review of 2015 again found significant gaps in training for SEND. Therefore, during 2016, the TDA produced a five-year plan to strengthen ITT. Part of this plan introduced an element making it compulsory for trainees to understand SENDCOP and how they might modify the National Curriculum in terms of pupil accessibility.

Today’s classrooms are though heterogeneous (Hodkinson Citation2019a) containing a range of children, some with complex learning needs. Successive legislation has continued to indicate that all teachers are teachers of SEND as such legislation assumes that they have adequate knowledge, skills and understanding to take ownership of the teaching and learning of children labelled as SEND (Sarginson Citation2017). Despite significant evidence as to the importance of effective training (DES Citation1978; Carrol et al. Citation2017) this fault line has remained at the core of government legislation. So, whilst a person may have completed teacher training and has been engaged to teach children labelled as SEND, they may do so without the skills, knowledge, or confidence to meet their needs. It appears, then, that little has changed since the Warnock Report of 1978. This history suggests that governmental initiatives in relation to new SEND legislative frameworks will continue to remain unsuccessful (Hodkinson Citation2009, Citation2019b, Citation2023).

Funding for SEND: is a ‘reboot’ of the thinking needed?

Analysis of the fault line that of funding to support the operation of SENDCOP details that SENDCOP 2015 placed the financial planning into the hands of Local Authorities (Las) despite past failures. In addition, LAs were also gifted opaque funding formulas, inconsistent procedures and financial constraints that made the operation of SEND services very complex (Taberner Citation2022). LAs had been accused, in the past, of maintaining a postcode lottery of provision (Hodkinson Citation2019a). This variation of funding observed some LAs building new special schools while others invested in expensive alternative provision. This legacy of funding provision continues today as there are still significant variations in high-needs block funding (Marsh, Gray, and Norwich Citation2022). This means that families are faced with unacceptable variations in levels of service provision. Such variations coupled with the complexities and lack of funding have acted as a barrier to the effective support of children. In 2018, the Local Government Association stated,

‘there has been a historic underfunding of high needs funding and a significant increase in the number of pupils with SEND. Whilst increasing funding … was a step in the right direction, it was never enough to meet increasing numbers of SEND pupils.’ (See Hodkinson Citation2019a, 22)

Funding then continues to be a significant fault line at the core of government policy. The past few years have observed a ‘war of words’ between schools and ministers (Perera Citation2019, 1). Schools say they are at a ‘breaking point’ while ministers continue to make ‘efficiency savings’ (Perera Citation2019, 2). Many leaders of children’s services have warned that funding is insufficient to meet the unprecedented needs they face and do nothing to avert an ‘impending crisis in SEND support’ (Hayes Citation2019, 1). This has led some to call for a ‘fundamental reboot’ to SEND funding system (Hayes Citation2019, 1). Given the size of the deficits, some LAs are facing, it appears that even the additional monies provided by the government will not ‘make a real dent’ in the funding issues facing schools and SEND services (Perera Citation2019, 8). To close this fault-line it seems clear that a radical reboot of the system is needed, one that provides a less opaque and simpler funding formula that has greater flexibility to ensure schools can respond, in real time, to the support needed by children (Perera Citation2019). As Tirraro stated,

‘Government and authorities need to stop clinging onto the models of old and forecast how the future of the world looks for SEND’ (Tirraro see Hayes Citation2019, 3).

Methodology

The data for this research were gained from a detailed analysis of Hansard with the research seeking to ascertain whether the ‘fault-lines of failure’, explored above, were observable within parliamentarians speeches. This analysis was framed from the implementation of the Children and Families Act (CFA), January 2014 through to May 2022 and centred on debates in the House of Commons. To aid in the search of Harvard, keywords were employed singularly and in combination. The keywords were ‘disability’, ‘special needs’, ‘special educational needs’, ‘additional needs’, ‘schools,’ and ‘primary’. The documents retrieved were searched for relevance and duplications. This resulted in 182 documents, containing 541,679 words, being subject to an initial analysis. After Braun and Clarkes (Citation2006) approach, the macro analysis involved each page of the documents being read several times. After such readings general areas of text were highlighted and so 167,305 words still held relevance. The subsequent microanalysis examined the demarcated sections through their lexicon, action and agency, voice, verb, and adjectives so as to reveal the parliamentarian’s conceptualisations and meanings (Park and Hodkinson Citation2017). At this stage codes, relating to the fault-lines, were placed onto the text (Essex, Alexiadou, and Zwozdiak-Myers Citation2021). The documents were then read again to indicate sections of text that provided important examples of the fault-lines (Finkelstein, Shama, and Furlonger Citation2021). Throughout this analysis questions were asked of the data:

Do the fault-lines of failure indicated above, appear in the data?

When did the fault-lines reveal themselves in parliamentarian speeches? and,

How did parliamentarians define and exploit the fault-lines?

Findings

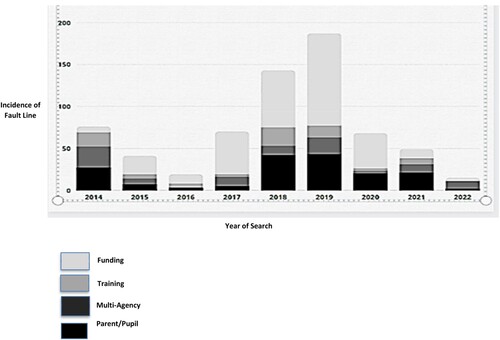

The search results are tabulated and graphed below.

Analysis and discussion

, and evidence that a wave of legislative dissatisfaction, centring on the fault lines, rose early in 2014 before ebbing slightly away in 2015 and 2016 as SENDCOP began to be operationalised. However, the data make plain that parliamentarians gave an early warning to the discontent that built in 2017 and overtopped the Government’s legislative surety in 2019. The data contain a wealth of information which the scope and size of this research simply do not allow to be fully examined. Therefore, analysis in this section will critically examine the main thrusts and themes chronologically that grew within the area of each fault-lines.

Table 1. Keyword Search.

Table 2. Incidence of the Fault Lines.

On the fault line of training . ..

In terms of training, parliamentarians appear to have been somewhat quiet. However, the data reveal some significant and concerning themes. For example, throughout the period 2014 to 2022 the government consistently stated that all children including those labelled with SEND should have access to world quality education systems, and that the ‘golden thread’ to this ‘high quality support … begins with ITT’ (Hansard Citation2021). Indeed, the government made clear in May 2018 that: ‘teachers and the training they receive is very much part of the strategy’ (Hansard Citation2018). Despite such rhetoric, as early as December 2014, politicians of all political persuasions, began to voice their concern, as example:

‘parents groups … report a lack of awareness on the part of health professionals, teachers, educators and LA professionals … this will impede progress…’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Many secondary schools have no specialist training…’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Clinical and education staff including SENDCOs, must receive initial and ongoing training’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘We do not seem to have the right balance in sharing skills that are available … So that expertise [in SEND] are utilised properly to help build knowledge, skills and training in mainstream … ’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Education settings, therefore, need to ensure that they give their staff the training necessary’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Early years providers, schools and colleges are responsible for deciding what specialist expertise required … we have been at pains to drive this point home that it is the responsibility of teachers … to have an understanding and awareness of SEND’ (Hansard Citation2020),

Analysis of Harvard though, counsels caution in accepting government rhetoric that: ‘all teachers are now trained in autism and other conditions’ (Hansard Citation2018). Drilling down into Hansard, reveals data that leads to the questioning of the quality and reach of this training. To provide just one example of concern, which relates to autism. The government announced in 2019, that since 2011, it had been working with the Autism Educational Trust, to provide more than 150,000 education staff, not just head teachers, teachers, and teaching assistants but also: ‘support staff such as receptionists’ (Hansard Citation2019). Whilst we should applaud such ‘training’ it must be placed into context. In 2018, there were 709,400 teaching staff and assistants working in maintained schools and colleges (DfE Citation2018) as well as 430,500 staff working in the early years settings (DfE Citation2018). Even without data for receptionists or midday supervisors, the government’s figures are somewhat tarnished. A Labour MP was very clear about the government’s commitment to training, stating that:

‘Sometimes we have such debates it can feel a little like Groundhog Day because the same sort of issues are repeated over and over again.’ (Hansard Citation2018)

‘There is certainly a case to be made for specialist training and for changes to the way we train teachers’ (Hansard Citation2019).

‘It is important for teachers to be trained to deal with children who have difficulties. At the moment there often supply teachers or temporary teachers who do not have the necessary skills, which could make a difference …’ (Hansard Citation2019).

‘[Teachers] … often they feel that they do not have the necessary skills …’ (Hansard Citation2020)

‘Teachers in classrooms do not always [have a] full understanding about different types of learning difficulty, so of course we go back to teacher training’ (Hansard Citation2021).

‘SENCOs, are brilliant, but they do not have the expertise, we would hope to have in these situations’ (Hansard 2022).

‘I want to ensure that people who work with children … have the training qualifications, skills, to make their lives a little simpler, although I have not managed this yet’ (Hansard Citation2015).

Pupil voice, funding, and multi-agency working

An analysis of this fault-line reveals a wealth of data relating to funding issues, time delays in the system, and that multi-agency working remained highly problematic throughout the period of data collection. However, in the space available here, it is intended to concentrate on two aspects within the data, that is exclusion/off rolling and how government appeared to ‘carry on regardless’ despite the voices that provided an early warning to the discontent that would be revealed in 2019. We should not forget though that in the early days the government trumpeted the new CFA as one which would: ‘place views, wishes, feelings and aspirations of children … at the heart of the system,’ and that through multi-agency working ‘genuine partnerships’ would develop (Children and Families Act Citation2014). Furthermore, government believed that:

‘Knowledge should not remain static. We remain open to suggestions and concerns of parents … to make sure that the work we are doing brings about a change in culture’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘[We are] in danger of operating in silos’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘All too often a silo mentality … [means that] action on the ground is impeded by a failure to work together’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Negativity about the potential of the CFA reforms, a legacy of an adversarial SEN system … a sense of cynicism’ (Hansard Citation2014).

‘Parents are battle hardened; they are also sceptical. Government needs to prove to them that their reforms mean that they don’t have to fight for the right education’ (Hansard Citation2014).

2015, was though a somewhat quieter year, no doubt because the SENDCOP had just been implemented. However, there were still some notable exchanges in Parliament, where it was observable that despite the fault lines beginning to open, government continued with their rhetoric of positivism:

‘Children with SEN must get the best possible education … That is what the EHCP has introduced … we are seeing more collaboration between schools across the system’ (Hansard Citation2015).

‘It is of course important that schools be held to account for all their pupils’ (Hansard Citation2015).

‘Does the honourable, gentlemen share concern that SEN children account for 65% of all exclusions … ?’ (Hansard Citation2016).

‘Schools are getting away with poor SEN provision … Schools have been given a loophole in the law to out difficult disabled children’ (Hansard Citation2016).

‘Many schools, deliberately or otherwise, defer or reject … children … because admitting such children would have an adverse effect on overall school results’ (Hansard Citation2016).

‘We have made fundamental changes to how SEND support systems worked for families, the biggest change in a generation … putting children and young people with SEND at the heart of the system’ (Hansard Citation2016).

Throughout the period 2017 to 2019 the trickle of dissatisfaction turned into a torrent of discontent as exclusions and the spectre of off-rolling entered MPs debates:

‘Children with special needs are increasingly being pushed out of the mainstream schools and they are grossly overrepresented in exclusion figures’ (Hansard Citation2017).

‘We have a real problem with the number of exclusions …’ (Hansard Citation2018).

‘Schools deliberately exclude children with autism, when they know they have an OFSTED coming’ (Hansard Citation2018).

‘In this brave new world … what happens to the children who nobody wants? The combination of high-stakes accountability created a perverse incentive for schools to off role and discourage children from attending mainstream’ (Hansard, Citation2018).

‘shockingly high exclusion rates … ’

‘Last year 20,000 children were off-rolled.’

‘I think there is a wild west of exclusions out there.’

‘[ I have a] feeling that something has to change, or schools will implode.’ (see Hansard Citation2018)

‘We recognise we are only part way to achieving our vision, the biggest issue we now face [is that we] have to address is changing the culture of LAs, clinical commissioning groups and education settings … We must overcome the barriers that prevent them from working together …’ (Hansard Citation2018).

With exclusions continuing to be of concern throughout 2019 to 2022, the government fell back on the safety net created in 2015. Hansard details the government became quick to ‘pass the buck’ when the failings in the system became obvious. Working with the government it appears that in 2018 Conservative MPs began to obfuscate the issues relating to multi-agency working. Whilst we mentioned early that in 2015 the government had ‘shared’ responsibility for the system’s success with schools in 2018 they also began to ‘share’ responsibility for its failures.

‘we are trying to cut down numbers of exclusions, [we] introduced EHCPs … ’.

‘we recognise challenges that LA’s face … which is why we have provided them with support to deliver the best value …’ (Government)

‘It’s about breaking down the silos on the ground, in reality, levers do not exist on the ground to deliver meaningful change … that was envisaged by the legislation’ (Conservative MP) (see Hansard Citation2018).

‘He stands at the dispatch box … as if everything is rosy, the parents know that is a load of rubbish’ (Hansard Citation2018).

‘The government can cite figures and dances around the issue, and we can cite figures back at them … primary heads wrote government … they are desperate for more money’ (Hansard Citation2018).

‘These issues are not new … they were certainly issues for the last Labour government.’ (Hansard Citation2019).

‘I put it on record that I share your concerns … the government will take action’ (Hansard Citation2019).

‘Problems remain political with respect to accountability, [there is] still substantial evidence of non-compliance with the 2014 Act … [it’s a] failure of political will on the part of councils’(Hansard Citation2020).

‘we need a consistent approach across the whole country to ensure that children get services and support they need’ (Hansard Citation2021).

‘The DfE is deflecting its responsibility for SEND pupils onto local government.’ (Hansard Citation2021).

‘[Children are] being forgotten, left behind and overlooked, waiting five years for a diagnosis’ (Hansard Citation2018).

‘Children are being tragically let down’ (Hansard Citation2020).

‘School exclusions have … shockingly tripled in five years’ (Hansard Citation2020).

‘Supporting children and young people with SEND is one of the most important roles of government … In 2014 we introduced major reform … and put [children’s] needs and their families at the heart of the system’ (Hansard, Citation2020).

‘The government are absolutely dedicated to supporting children with SEND and their families, [our] ambition for them … is to ensure a world-class education system that sets them up for life’ (Hansard Citation2021).

‘Heartbreakingly, the picture facing schools supporting children with SEN is bleak. School budgets are at breaking point … schools and LAs are struggling to meet the needs of children … the SEN code is no more than empty promise’ (Hansard Citation2020).

Conclusions

Research (Hodkinson Citation2023) demonstrated that SEND legislation that had operated in England since 1981 had been subject to recurring fault-lines which coalesced around pupil voice, multi-agency working, training, and funding. This research suggested that various government had been told that SEND legislation of the past 40 years had not been fit for purpose. The evidence gained from this current research confirms that of earlier research denoting that the ‘fault-lines of failure’ were evident within the speeches of parliamentarians recorded in Hansard from December 2014 until May 2022. The current analysis details that politicians, of all political persuasions, told government where the fissures in their legislation were. However, despite overwhelming evidence the government did not listen to the voices of parliamentarians and their concerns preferring it seems to carry on with legislation that was built upon child deficit and a policy that placed LAs in a perverse duality of being the provider and the limiter of services and resources that support children labelled as SEND. Furthermore, and despite its early rhetoric, the government did not place the child and their families at the heart of legislation nor really tackle, with any relish, the issue of the training of professionals working in multi-agency teams. In short, their legislation did not lead to radical cultural change. Indeed, they never really seem to start this process. It appears that if new SEND legislation is to be effective then the government must listen to and hear and heed voices that offer wise counsel and efficient solutions to preventing legislative failing – namely parliamentarians. Problematically, though, as Petronius Arbiter stated around 2,000 years ago – we have known for time immemorial what governments do to avoid radical culture change. It appears that current SEND legislation is covered in much the same rhetorical illusion of progress. As he said:

‘We trained hard—but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we were reorganised. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganising, and what a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while actually producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralisation.’

Petronius Arbiter legionos Director of Elegance AD 27- 66 (Brittania.com)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Ahad, A., A. M, Thompson, and K. E. Hall. 2022. “Identifying Service Users Experiences of the Education, Health and Care Plan Process: A Systematic Literature Review.” Review of Education 10 (1): 1–24.

- Atkinson, M., A. Wilkin, A. Stott, P. Doherty, and K. Kinder. 2002. Multi-Agency Working: A Detailed Study. London: National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Basingstoke, M. 2008. Hansard – Col. 589-600.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Pyschology.” Qualitative Research in Pyschology 3: 77–101.

- Boesley, L., and L. Crane. 2018. “‘Forget the Health’ and Care and Just Call Them Education Plans: SENCOs Perspectives on Education, Health and Care Plans.” Jorsen 18: 36–47.

- Capper, Z. 2020. A cultural Historical Activity Theory Analysis of Educational Pyschologists Contributions to the Statutory Assessments of Children and Young People with Special Educational Needs post 2014 Children and Families Act. Unpublished Ph.D, University of Birmingham.

- Care Co-ordination Network United Kingdom. 2004. Information Sheet. Available at: www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/rworks/jan2004-1.pdf.

- Carrol, J., L. Bradley, H. Crawford, P. Hannant, H. Johnson, and A. Thompson. 2017. SEN Support: A Rapid Evidence Assessment Research Report July 2017. London: DfE.

- Cavet, J. (n.d.). Working in Partnership Through Early Support: Distance Learning Text Best Practice in Key Working: What do Research and Policy Have to say? London: Care Co-ordination Network UK.

- Cheminais, R. 2009. Effective Multi-Agency Partnerships: Putting Every Child Matters Into Practice. London: Sage.

- Children and Families Act. 2014. [online] Available at: http://www.ccinform.co.uk/children-families-act-2014/#adoption

- Community Care. 2022. Serious Case Reviews into Toddler Murders Highlight Social Work Staffing and Oversight Failures. Available at: https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2019/06/06/serious-case-reviews-toddler-murders-highlight-social-work-staffing-oversight-failures/.

- Corbett, J. 2001. Supporting Inclusive Education: A Connective Pedagogy. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Cullen, M. A. R., and G. Lindsay. 2019. “SEN Understanding Drivers of Complaints and Disagreement in the English System.” Frontiers in Education 4 (7): 1–14. doi:10.3389/feduc2019.00077

- Department for Education and Science. 1978. The Warnock Report:Special Educational Needs Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Education of Handicapped Children and Young People. London: HMSO.

- Department for Education and Employment [DfEE]. 1998. Meeting Special Educational Needs: A Programme for Action. London: DFEE.

- Department for Education [DfE]. 2018. Survey of Childcare and Early Years Providers: Main Summary, England, 2018.Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1039531/Survey_of_Childcare_and_Early_Years_Providers_2018_Main_Summary_revised_December2021.pdf.

- Edwards, A., D. Daniels, T. Gallagher, J. Leadbetter, and P. Warmington. 2009. Enhancing Inter-Professional Collaborations in Children's Services: Multi-Agency Working for Children's Wellbeing (Improving Learning Series). London: Routledge.

- Essex, J., N. Alexiadou, and P. Zwozdiak-Myers. 2021. “Understanding Inclusion in Teacher Education- A View from Student Teachers in England.” International Journal of Inlcusive Education 25 (12): 1425–1442.

- Finkelstein, S., U. Shama, and B. Furlonger. 2021. “The Inclusive Practices of Classroom Teachers: A Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (6): 735–762.

- Hansard. 2014. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2015. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2016. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2017. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2018. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2019. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2020. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hansard. 2021. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk

- Hayes, D. 2019. Factors for SEND Funding Crisis. Children and Young People Now. Available at: https://www.cypnow.co.uk/features/article/factors-for-send-funding-crisis.

- Hodkinson, A. 2009. “Pre-Service Teacher Training and Special Educational Needs in England 1970-2008: Is Government Learning the Lessons of the Past or Is It Experiencing a Groundhog Day?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 24 (3): 277–289. doi:10.1080/08856250903016847

- Hodkinson, A. 2019a. Key Issues in Special Educational Needs, Disability and Inclusion (3/e). London: Sage.

- Hodkinson, A. 2019b. “Pre-Service Teacher Training and Special Educational Needs in England 1978-2018. Looking Back But Moving Forward?” In Including Children and Young People with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities in Learning and Life. How Far Have We Come Since the Warnock Enquiry – and Where Do We Go Next?, 36–41. London: Routledge.

- Hodkinson, A. 2023. “The Death of the 2015 Special Educational Needs Code of Practice and the ‘Parable’ of the Drowning man. Should Government Have Learnt Lessons from Listening to the Voices of History, Research and Politicians? (Part I).” Education 3-13, Online First.

- Hussain, H. D., and S. Brownhill. 2014. “‘Integrated Working: From the Theory to the Practice’.” In Empowering the Children’s and Young People’s Workforce Practice Based Knowledge, Skills and Understanding, edited by S. Brownhill, 193–209. London: Routledge.

- Jahans, K., and A. Bayton. 2022. “Safeguarding Communications Between Multiagency Professionals When Working with Children and Young People: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 35: 171–178. doi:10.1111/jcap.12363

- Kaehne, A. 2014. Multi-Agency Protocols as a Mechanism to Improve Partnerships in Public Services, Local Government Studies, 2014. Available at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108003003930.2013.861819#preview.

- Lamb, B. 2019. “Statutory Assessment for Special Educational Needs and the Warnock Report, the First 40 Years.” Frontiers in Education 4: 5–1. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00051

- Marsh, A. J., P. Gray, and B. Norwich. 2022. Fair Funding and Levelling Up for Pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disability in England 2014 to 2023. Available at:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358867574_Fair_funding_and_levelling_up_for_pupils_with_special_educational_needs_and_disability_in_England_2014_to_2023.

- Ofsted. [Office for Standards in Education]. 2003. Special Educational Needs in the Mainstream. London: HMSO.

- Park, J., and A. Hodkinson. 2017. “'Telling Tales'. An Investigation into the Representation of Disability in Classic Children's Fairy Tales.” Educational futures [online] 8 (2). Available at: https://educationstudies.org.uk/?p=7624

- Payler, J., and J. Georgeson. 2013. “Multiagency Working in the Early Years: Confidence, Competence and Context.” Early Years: An International Research Journal 33 (4): 380–397. doi:10.1080/09575146.2013.841130

- Perera, E. 2019. High Needs Funding: An Overview of the Key Issues. Education Policy Institute April 2019 Research Area: Education Funding. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/33298/1/EPI_High-Needs-Funding_2019.pdf.

- Perry, J. 2014. “England: SEN measures-Implementation.” British Journal of Special Education 41 (3), doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12075

- Sarginson, E. 2017. An Investigation into Special Educational Needs Training and the SENCO‘s Role in Practice Change a Qualitative Review. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Manchester.

- Stone, B., and P. Foley. 2014. “‘Towards Integrated Working’.” In Changing Children’s Services: Working and Learning Together (2nd ed.), edited by P. Foley, and A. Rixon, 49–92. Bristol: Policy.

- Taberner, J. 2022. “There Are Too Many Kids with Special Educational Needs”. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357679505_There_are_too_many_kids_with_special_educational_needs_Squires_2017.

- Teacher Development Ageny [TDA]. 2008. Available at: www.tda.gov.uk/teachers/sen/support_teachers_and_trainers.aspx.

- Watson, D., R. Townsley, D. Abbott, and P. Latham. 2002. Working Together? Multi Agency Working in Services to Disabled Children with Complex Health Care Needs and Their Families: A Literature Review. Birmingham: Handsel Trust.

- Webb, C. J. R. 2022. “More Money, More Problems? Addressing the Funding Conditions Required for Rights-Based Child Welfare Services in England.” Societies 12 (9): 1–19. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/182139/

- Winter, E. C. 2006. “Preparing new Teachers for Inclusive Schools and Classrooms.” Support for Learning 21 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9604.2006.00409.x