ABSTRACT

In the new Curriculum for Wales (Cwricwlwm i Gymru) which is phasing in from September 2022, the concept of ‘cynefin’ (‘the place where we feel we belong’) is core to developing children’s understandings of place and identity. While cynefin has long been considered in a wider cultural and heritage context in Wales, it is not yet clearly understood in education, and is rarely explored from the pupil perspective. Drawing on data gathered from four primary schools in Wales (n = 67 children, aged 7–10), using the method of photo elicitation to scaffold talk, this article explores children’s understandings of what cynefin means to them. Themes of people, place, activity, and emotions/feelings emerged, which interconnected in multiple, non-linear, and unique ways, indicating the importance of nuance in primary-level curricula design.

Introduction

From September 2022, schools in Wales will start to follow a phased introduction of a new statutory Curriculum for Wales (Cwricwlwm i Gymru), which has been described as a ‘bold new vision for curriculum, teaching and learning’ (Sinnema, Nieveen, and Priestley Citation2020, 181). Representing the culmination of many years of education system-level reform in Wales (Evans Citation2022), there are some echoes of the Curriculum for Excellence in Scotland, as a result of ‘transnational policy actors’ (Hulme, Beauchamp, and Clarke Citation2020, 498). The new curriculum requires teachers to move beyond being a compliant ‘policy actor position of receiver’ (Aldous, Evans, and Penney Citation2022, 499) to ‘continually shift between or actively combine multiple policy positions – as narrators, translators, receivers, and in some moments entrepreneurs, in enactment of the new curriculum’ (511). Through a re-envisioned curriculum leadership role for teachers, this role as local curriculum makers (Crick and Priestley Citation2019) aspires to contribute to school and wider system-level improvement (Harris, Jones, and Crick Citation2020). This is because the Welsh Government (Citation2022) assert that ‘It is for schools and practitioners … to decide what specific experiences, knowledge and skills will support their specific learners’. The intention is a curriculum designed in Wales and for Wales (Welsh Government Citation2022), whereby

Learners should be grounded in an understanding of the identities, landscapes and histories that come together to form their cynefin … Wales, like any other society, is not a uniform entity, but encompasses a range of values, perspectives, cultures and histories … [which are] … not simply local but provide[s] a foundation for a national and international citizenship. (Welsh Government Citation2022)

Literature review

To contextualise the concept of cynefin, both in its broader sense of belonging and its specific position in Wales and the Welsh language, it is necessary to analyse both international curricula and academic research. The structure of the review, below, will adopt this layered approach.

‘Belonging’ in international curricula

The concept of ‘belonging’ appears in a number of curriculum guidelines in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres, including the new Curriculum for Wales which is the core focus of this study. Yuval-Davis (Citation2011) talks about belonging and the social and emotional importance of feeling safe and ‘at home’, and highlights the importance of belonging not just as a personal consideration but also in relation to complex social, political, and cultural influences. Similar lack of consistency in meaning is highlighted by Piškur et al. (Citation2022), who analysed how belonging is portrayed in the curriculum guidelines of five European countries – Netherlands, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. They note that the actual term ‘belonging’ is an uncommon word in the guidance, but the concept is explored using words like ‘community’, ‘participation’ and ‘values’, and they recommend that the concept of belonging warrants further academic exploration.

In Ireland, the Early Childhood Aistear, the curriculum framework for all pupils from birth to age 6, uses four interconnected themes to describe pupils’ learning and development: Well-being; Identity and Belonging; Communicating; and Exploring and Thinking. The theme of Identity and Belonging is about pupils developing a positive sense of who they are and feeling that they are valued and respected as part of a family and community. In a literature review to support the update of Aistear, French et al. (Citation2022, 237) highlight:

the importance of recognising that children’s learning and development results from their unique and dynamic socio-cultural contexts; children’s learning and knowledge-building is supported and given meaning through everyday experiences and participation in their family and community.

Murphy (Citation2013, 807) also highlights the related concepts of dùthchas (Scottish Gaelic) or duchas (Irish Gaelic), which are ‘emotive’ and, like cynefin, hard to translate into English. Murphy (Citation2013, 807) continues to explain that, although conscious of oversimplifying a complex idea, dùthchas is ‘being-in – place (in a cultural sense rather than in an existential one); captures the way that land, people and community, past and present, are connected – connections which are maintained by practices, language and other means’. Meighan (Citation2022) also connects the Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic words, but adds an extra dimension, beyond people and place, by asserting that dùthchas ‘stresses the interconnectedness of people, land, culture, and an ecological balance among all entities, human and more than human’ – the latter echoing connections to the other-than-human world discussed by Adams and Beauchamp (Citation2022) in relation to cynefin.

Further afield, in New Zealand, tūrangawaewae, meaning a ‘place to stand’, or the ‘ground and place which is your heritage and that you come from’ (Kahu et al. Citation2022, 11) is seen as a foundational education principle (Berger and Johnston Citation2015). Its early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki, is underpinned by the vision that pupils are ‘secure in their sense of belonging’ (Ministry of Education Citation2017, 5). Similarly, Australia’s national early childhood curriculum, Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF; Australian Government Citation2009), situates belonging as the lead concept. The curriculum outcomes refer to developing a child’s strong sense of identity, pupils connecting with and contributing to their world, pupils having a strong sense of wellbeing, and the importance of pupils drawing on a sense of belonging to be confident and involved learners.

Such statements of intent, however, need to be tempered by concerns about implementation. For instance, when considering opportunities and risks arising from the belonging motif in the Australian framework, Sumsion et al. (Citation2018) question why there appears to be very little guidance provided about how it might be implemented or conceptualised beyond the level of everyday explanations and understandings. In addition, in Wales a note of caution is raised by the ‘Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communities, Contributions and Cynefin’ in the New Curriculum Working Group Final Report (Williams Citation2021, 53), which identified the need to interrogate some of the assumptions that underpin the concept of cynefin within the curriculum and

… to question its applications in a highly mobile, interconnected world, where place, history and belonging often defy national boundary … this concept may encourage an interpretation of belonging associated with roots rather than routes to Welsh citizenship, servicing ideas of us and them, locals and others, in which the claims of some are seen as more authentic than others.

Cynefin and belonging in academic literature

Cynefin is a difficult concept to define and will potentially have individualised meanings for each learner. Although the word now features in education, previous academic literature has been focused on its use in business and geography. In business, for example, Snowden (Citation1999, 36) first used the analogy of cynefin as a ‘concept of wholeness and history’, where organisations develop ‘trusted relationships and confidence that comes from a community with common values’. The label ‘cynefin’ was used for a subsequent sense-making framework with four domains (complex, knowable, known, chaos) (Kurtz and Snowden Citation2003). Although these conceptualisations utilise the label ‘cynefin’, in reality they offer little for schools to apply within the curriculum.

In terms of geography, the word ‘cynefin’ is not used explicitly, but it is implicit in thinking about place-conscious education. This aims to explore the ‘perceptual, cultural, ecological, and political dimensions of place’ (Gruenewald Citation2003, 646), and how this shapes the educational experiences and cynefin of pupils. Like cynefin, place-conscious education has many dimensions, including the promotion of equity in the classroom (Vander Ark, Liebtag, and McClennen Citation2020) and the exploration of ecologies of literacy (Pahl and Allan Citation2011).

The Curriculum for Wales (2022) frames cynefin as an element in the development of learners’ identities. This resonates with the concept of funds of identity (Esteban-Guitart and Moll Citation2014) which recognises the foundation of identity that pupils themselves construct. Building on the concept of funds of knowledge (Gonzalez, Moll, and Amanti Citation2005) and its acknowledgment that families and communities are a resource in pupils’ education, ‘funds of identity’ recognise that pupils’ identities develop from the complex interaction of family and community resources as well as the child’s individual disposition. Learning happens when connections are made between the learners’ funds of identity and new material/ideas. Schools that have an insight into their learners’ funds of identity are well placed to prevent the marginalisation of minoritized students (Hogg and Volman Citation2020) and address some of the challenges of cynefin that are highlighted by Williams (Citation2021).

Adams (Citation2022, 2) asserts that the word cynefin also ‘provides insight into ways of knowing and states of being that are alternative to the dominant epistemologies and ontological stances in mainstream education yet in keeping with place-based pedagogy’. He reports a conversation with a Welsh-speaking hill farmer, who described his concept of cynefin as how sheep ‘might wander off during the day, but they would always come back to their part of the land, their cynefin’, but then related it to himself by stating that ‘It's the same with me. If I've been away on a journey and I come back, I can feel it, the land when I come back, my cynefin’ (Adams Citation2022, 4). Such views highlight the influence of personal history and place in developing a sense of cynefin, but also indicate that such views can be very personal to an individual and their circumstances.

Academic studies of cynefin also raise challenges with which schools are confronted as they implement their new curricula. For instance, Adams and Beauchamp (Citation2022) note that cynefin could potentially help educators ‘to feel emboldened to create opportunities for their learners where alternative states of being, and ways of knowing, are encouraged’ (15).

Sampling and sample

To explore primary pupils’ perceptions of cynefin, a purposive, convenience sample of 67 pupils aged 7–10 years from four primary schools, geographically spread around Wales, was recruited through existing university networks (see ). All schools serve diverse communities in terms of race, ethnicity, culture, and language.

Table 1. Sample.

Method

To explore pupils’ unique and nuanced perceptions of identity, culture and belonging, the study adopted a qualitative approach. As a starting point for this work, the sample of pupils were considered to be ‘experts in their own lives’ (Clark and Statham Citation2005, 460). As such, the project fostered a participatory approach, whereby data collection was child-centred and hands-on, enabling the pupils to construct meaning through the research process and share it with the researchers. In other words, the research was by and with pupils, not conducted ‘on’ them (White et al. Citation2010). The approach also reflected the prominence of pupil voice in the Wales context, in terms of the legal and policy frameworks that support pupils’ rights (Tyrie and Beauchamp Citation2018).

In light of the above, we wanted to use a research method that gave the pupils agency (Clark and Statham Citation2005). Photo elicitation, here defined simply as ‘a visual research method which uses photographs as a stimulus for talk … which can be used by pupils’ (Cooper Citation2017, 625), provided an appropriate ‘participant-driven approach’ (Vigurs and Kara Citation2017, 515) that is suitable for use with primary age pupils (Shaw Citation2021). With this method, images are used as the stimulus for interviews to enable participants to ‘describe to the researcher the meaning and significance of their images as well as their perspectives and understanding thereof’ (Joubert Citation2012, 454). This method has the potential to provide ‘fascinating empirical data and provide unique insights into diverse phenomena, as well as empowering and emancipating participants by making their experiences visible’ (Oliffe and Bottorff Citation2007, 850). Such an approach also provides the opportunity for capturing voices that are not usually heard (Wilson et al. Citation2008).

To generate the pictures for use in the interviews, the sample pupils (who were all confident users of technology) utilised existing school equipment such as iPads and computers. The original intention of the study was to use auto-driven photography (also known as native, reflexive or participant-generated images) (Ford et al. Citation2017), where the pupils would capture images of ‘things that are important to them in a particular context’ (Guillemin and Drew Citation2010, 176). However, in reality, we had to accept ‘uncertainty and discomfort as essential travel companions’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2022, 12) and make some adaptations to the approach due to prevailing concerns in the schools during the immediate post-COVID timing of the study.

Hence, in response to these uncertainties and to allow for some flexibility, the pupils were also permitted to use ‘found data’ (Wiles et al. Citation2008, 4) obtained through online image searches conducted in the safety of the classroom setting. In both image-sourcing activities, the pupils played an integral role in the generation of their chosen images, with sensitive facilitation by researchers (who were experienced in working with primary school pupils) and their teachers. As a result, the pupils had a high level of autonomy. They were encouraged to take, or find, a maximum of four digital images of social and/or material surroundings of anything that had meaning to them. For ethical reasons, the images did not include people.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by Aberystwyth University’s Ethics Panel for all university partners. Informed consent was sought from parents and practitioners and, most importantly, from the pupils who participated.

This ‘procedural ethics’ (ref) was also accompanied by more informal considerations of ‘ethics in practice’, or ‘everyday ethical issues that arise in the doing of research’ (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004, 263). For instance, ensuring the potential disruption of the research to pupils’ education was minimised. In their role as co-researchers, the classroom teachers embedded the collection of images as a classroom or homework task with opportunities for the pupils to collect images at home, within their local community, or from image searches in the classroom.

The final ethical considerations related specifically to visual data. As the image collection was predominantly embedded in classroom activities, or under parental supervision through homework, there was little danger of the pupils accessing inappropriate images. In addition, if any inappropriate images were provided by the pupils, there were clear protocols in place through university and school policies to handle such a situation. As all interviews took place in school settings, there was an added layer of protection.

Data collection

Four members of the research team undertook data collection through small group interviews, with a maximum of four children in each group. The interviews were conducted in three schools by members of the research team, but a researcher was unable to visit one school due to their prevailing post-COVID visiting rules. In this case, the interviews were conducted by the classroom teacher using the same agreed prompts. Whilst the data from this particular school was arguably comparatively limited, because it was not possible for a researcher to prompt for more detailed responses, it was still included in the overall dataset for analysis.

All the pupils showed their chosen pictures during the interviews, either in print form or on a tablet/iPad. These images were used as the visual stimulus for group interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. These interviews were semi-structured around agreed open prompts, such as ‘Can you tell me about your image?’, together with sensitive follow-up questions to elicit detailed responses. All the pupils talked about their images and what they represented and, in some instances, chose to explain the reasons for their choices by sharing associated stories and/or experiences.

Data analysis

The images used in this study were ‘neutral tools in the research process’ (Lipponen et al. Citation2016, 937), in the sense that no attempt was made to read further meaning into the images by analysing them. The main data source was therefore the ‘voice’ of the pupils in the interview transcripts. The analysis followed a hybrid (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006) approach to thematic analysis to ‘understand the situated nature of participants’ interpretations and meanings’ (Ezzy Citation2002, 81). The initial codes reflected the focus of the research study (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006, 84), while also allowing the generation of new codes and themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). The analysis followed Nowell et al.’s (Citation2017) approach to qualitative analysis to achieve ‘trustworthy’ outcomes as a team. Members of the research team met after each stage of the data-gathering, for discussion and debriefing, to agree on the coding generated through their analyses. This approach allowed for ‘open coding’ and involved ‘a constant moving back and forward between phases’ (Nowell et al. Citation2017, 4), using diagramming as appropriate to develop iterations of a final model (discussed later in this paper). Other members of the research team provided externality to the analytical process, particularly in developing iterations of the final model.

Discussion and findings

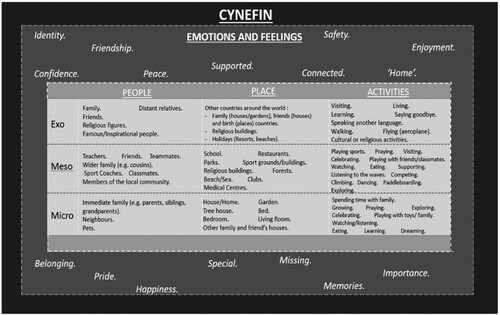

As no significant differences in findings were identified between the schools, they are reported as a whole. The analysis generated four key themes that outline what shaped the pupils’ sense of cynefin:

People

Place

Activity

Emotions/feelings

In addition, we identified three dimensions to each theme, which were initially categorised as micro, meso and macro. The term macro, however, which implies coverage of larger societal issues such as ideology, cultures, social norms, policy and so on (Piškur et al. Citation2022), presented some challenges due to its lack of connection to the pupils, who reflected much more personal concerns. In this context, Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979, 7–8) concept of exo-systems seemed to better represent a larger scale whilst retaining a personal connection, where a child ‘may never enter (a setting) but in which events occur that affect what happens in the person’s immediate environment’. The dimensions explored in this study are hence described as:

Micro: home and immediate family

Meso: local community, including school, clubs, places of worship, family living locally

Exo (akin to ‘Cynefin beyond Wales’): extended family, family history, holidays, visits.

The four themes and three dimensions are not hierarchical in nature, but constantly interact on multiple, non-linear levels. These are examined in detail below, using pupil-voice quotes from the interviews to exemplify and explore ideas. Each child is identified by a code (e.g. CG4) to ensure anonymity. After each theme has been discussed, it will be incorporated into a final conceptual model to demonstrate the emergent patterns of non-linear interactions.

Theme 1 – people: the importance of ‘who’ in the development of cynefin

During the data collection process, the pupils were encouraged to create or find and share photographs of places/things that were important to them. The pupils were told not to photograph or use pictures that contained people. However, when prompted to explain why they had chosen their photograph, the pupils often highlighted the significance of the connections it had to the people in their lives. Such connections clearly shaped their perceptions of cynefin and what they considered to be important to them.

On a micro scale, these were reflected by the importance of immediate family, often prompted by choosing pictures of their homes. Typical quotes included:

The importance of wider family at a micro level is demonstrated by the following interview extract:

The picture is my Nana's house. And I was it. It's a place where I feel safe. I guess it feels like my house. And I feel really safe.

So tell me about your picture. Why that place is really important to you?

It is my Nana's house. And when I was born, she always used to look after me and take care of me and every time we go there, she always spoils us. We always go there at Christmas and after school. (WG1)

I feel happy, because if [name of football team] score goals he [dad] would lift me up. And we would all shout and we would be very happy if [name of football team] won the match. (WG7)

I chose the (local monument) because [it] is really important to our school and community. (CG2)

… I have the best teacher and support system (CG1)

My picture is not in Wales … I don’t have any grannies or grandpas here, I only have them in Bulgaria. And that is why this is more important. (WG4)

This was my family garden in Nigeria … this one makes me the saddest because I really miss my friends (AG1)

I think it’s an important part of connecting. So not just the place but the people you go with to the place (WG4)

I have friends and see lots of the same people; they help me feel I belong. (WG8)

In many cases, people were a fundamental part of the pupils’ feeling of safety, with home, garden or school as the places they shared with family members at the micro level. As noted above, however, the borders between different levels are porous and can span from micro and exo level, often within a single image. For example, a child talked in detail about photographs of family from Nigeria (exo), who appeared in their chosen picture of the main room in the family home (micro). Thus, the child’s sense of belonging was rooted in the security of a family with international ties, capturing their complex ‘funds of identity’ (Esteban-Guitart and Moll Citation2014). Similar experiences were explored by pupils talking about their grandparents, who lived in Bulgaria or Sri Lanka; in these cases, the images were of locations outside Wales, demonstrating the need to develop a conception of cynefin which reaches beyond the geographical borders of a country.

Theme 2 – place: the importance of ‘where’ in the development of cynefin

As a concept, cynefin has often been centred around ‘place-based identities’ and ‘place-making’. The Curriculum for Wales (2022) emphasises ‘identities, landscapes and histories’. This understanding of cynefin has remained focused on localities and how this shapes individuals’ perceptions of themselves, others, and the world. In our data, the responses resonated with Antonsich’s (Citation2010, 646) notion of ‘place-belongingness’, where a place, not necessarily a domesticated or material space, is felt as ‘home’ and is a ‘symbolic space of familiarity, comfort, security, and emotional attachment’. When asked to choose an image of a place that was important to them, many of the pupils chose to focus on private spaces of personal significance and spoke about safety and comfort. Many pupils chose pictures of their houses (often a specific room therein), their gardens, or the immediate area outside their homes, reflecting the micro level. For instance, on a micro level, typical responses included:

My safe place is my home because I feel that I belong because … well … it reminds me of the reason that I’m in this world – family, friendship and kindness. It makes me feel right and it makes me feel like I belong (T4)

My place is my bedroom. I can lie in my bed and think about everything that’s happened that day, and that week, and I can dream about what’s happening tomorrow. (T14)

Also, I have a picture of my room inside, this has my most valuable items (CG1)

My picture is my garden. And I chose it because we have lots of special parties there. And it makes me feel special … (AG3)

This mosque is important to me (CG5)

I put down [name of rugby team] RFC because that is the rugby team that I play for and I feel safe there and I enjoy it (T2)

My next one is the Medical Centre. They are such a great help (WG3)

[name of local facility] because I go bowling and to the cinema with my family (CG2)

I put the library because I like to read … I get to choose new books … it’s close to me and it’s like really big (CG4)

At an exo level, the pupils also demonstrated that the importance of cynefin is not just rooted in the local. Indeed, their sense of Cynefin was shaped by places all over the world (even if they had never visited them) and ultimately shaped how they saw themselves and the processes of place-making within their current locality. Responses reflected the diversity of the sample pupils, including:

Sri Lanka is my home (WG3)

My first picture is of Honduras, where I am from. It is important to me, but I have never been able to go there (CG1)

(Talking about the Blue Mosque) “This is in Turkey Istanbul and that is why it is special to me” (CG3)

My picture is of Ireland. We go there every year to remember my Great-Great Grandmother (T19)

And I like playing football with my dad. And it also makes me feel magical because I have a fairy garden on the bottom of my garden.

The fairy garden’s not on the pictures.

I know but it's kind of like in the corner.

Do you want to tell us about the fairy garden? That sounds really interesting.

So, the fairy garden is where we leave stuff out for the fairies, and they come and replace it with something else. … we put plants and stuff in it. And if stuff, if like stuff crumbles up, we replace it with something new. And one time I accidentally broke the swing, and the night fairies replaced it with a new one.

It appears that the importance of places assigned by the pupils may not always be obvious to others. This accords with Rasmussen’s (Citation2004) distinction between ‘places for children’ (largely fixed in time and prescribed by others), and ‘children’s places’ (largely personal and ephemeral, therefore subject to change when the child’s relationship with the place changes). Rasmussen (Citation2004, 171) suggests that we should therefore be aware of children.

as social and cultural actors who create places that are physical and symbolic and call attention to ‘the interfaces’ between adults’ understanding of what one can and should do in a place for children and children’s understanding of this matter.

Theme 3 – activity: the importance of ‘what’ in the development of cynefin

Our data highlight that it was not always just the place or the people that made it special and important to the pupils’ sense of cynefin, but rather the activities that they undertook on their own or with others. In other words, just being in a place was not always enough, and activities added another dimension. The types of activity were many and varied, and often overlapped at all levels (as previously mentioned) with other themes, especially people. For example, some pupils illustrated the importance of this on a micro level, by discussing what they do in their homes and gardens:

I like to dig up potatoes and plant stuff (AG2)

My mum lets me eat food out in the garden. I like playing with my brother on my little tree house and playing football there (AG2)

I like playing football with my dad (AB3)

We would all shout and we would be very happy if [name of football team] won the match … I would be part of the community watching the football. (WG7)

I love to go there [beach] with my family and go on my paddleboard. I like to climb the rocks with my mom. (AG3)

My place is [name of] dance company. I chose [name of] dance company because when I am there it makes me happy, and I feel safe. (T9)

“It is in South Africa where I liked to walk.” … “We walked everywhere there because we did not have a car. We walk everyday here.” (WG6)

This is a photo of the temple in India that me and my family go to. (CG4)

This was in my family garden in Nigeria (Picture of them gardening) (AG1)

Theme 4 – emotions and feelings: the affective aspect of cynefin

The varied combinations of the themes above led to the articulation of a wide range of emotions and feeling by the pupils. These transcended the micro, meso and exo levels and represented another dimension of cynefin. Examples from the interviews below are indicative of the wide range of emotional responses described by pupils:

It feels like my home with my friends. (In context of going to a dessert restaurant with friends) (WG3)

This one makes me the saddest because I really miss my friends. (AG1)

So that this is why it's special to me because when I went there, I felt confident (talking about a visit to a mosque in Turkey) (CG5)

So, hearing the waves on the beach in Wales makes me feel like I am supposed to be here. … So, when you to the beach everything is calm, so you feel calm yourself. (WG7)

… I feel happy relaxed and at peace (CG2)

Developing a model of cynefin

When analysing the data as a research team, it was helpful to use an iterative process of diagramming (Nowell et al. Citation2017) to analyse the relationship between the various themes that were generated. The aim was to develop an understanding of how the pupils in this study constructed their sense of cynefin, starting with ‘an emphasis on the embodied lived experience of place’ (Hackett Citation2014, 10). In examining different visualisations of data, it became apparent that Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) original ecological theory offered the best way of representing our findings. More specifically, we found that Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979, 3) conception of an ecological environment as ‘a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like a set of Russian dolls’ was particularly suitable, so it provided the starting point for the framing of a model. It is worth noting, however, that our model does not reflect Bronfenbrenner’s later work (particularly the concept of time) because this study focused on a moment in time, rather than on time as developmental processes. This was seen as unproblematic because, as Tudge et al. (Citation2009, 207) point out, ‘Bronfenbrenner never implied (let alone stated outright) that every aspect of the model had to be included within any study’.

In our new model (), the outer ‘doll’ is cynefin, with emotions/feelings, and then people, place and activity nested within it. It is important to note, however, that the boundaries between ‘dolls’ or elements of the model are porous, and are thus represented by dotted lines. We define people, place and activities as the core domain of the model (each with three levels: micro, meso and exo), with emotions/feelings as the affective domain, and cynefin as the conceptual domain. There is an element of directionality only in so far as cynefin begins in the core, which evokes an affective element, and the synergy of both create a sense of cynefin, but since this is not linear or predictable it is not included in the model. For example, ‘family’ might appear in any other core element depending on physical and emotional proximity, and the activity being undertaken (if any). Therefore, we suggest that people, place and activity on their own do not represent cynefin, unless they generate an affective response (feelings/emotions). In this model, words from the pupils are used to represent the range of emotions reported, but we do not try to link these to a specific activity or suggest that they all need to be present to generate a sense of cynefin. In addition, we suggest that individually people, place or activity (at any level) can each generate an affective response, leading to a sense of cynefin. Or, any combination of the core elements has the same potential to create an affective response, particularly linking people to place and activity, leading to cynefin.

Conclusion

The model of cynefin for primary school pupils in this study, authentically articulated through pupil-voice, reflects our belief that ‘children’s perspectives of their world are unique’ (Joubert Citation2012, 452), and need to be captured through the research process. The concept of cynefin is an important feature of the new curriculum in Wales, but is as yet not clearly understood, certainly from a pupil perspective. While we acknowledge the possible limitation that the model is based on a small-scale sample (n = 67 primary school pupils from four schools), what has emerged is the fact that cynefin is individual to each pupil. As such, this reflects the importance of ‘my feelings, my thinking, my experience, my lived-body awareness’ (author italics) (Pulkki, Dahlin, and Värri Citation2017, 215). Indeed, the ways in which the pupils described cynefin echoes the Welsh-speaking hill farmer described by Adams (Citation2022, 4), who talked of ‘my cynefin’ (our emphasis). We suggest that, as cynefin is integrated into the new curricula being developed by primary schools in Wales, teachers need to be aware that it is not a generic, abstract concept, but is unique to each pupil. To explore this with pupils, we suggest that visual methods are a useful tool for unlocking the core domain of people, place and activity and could be used in further research in this are to build on the model outlined in this article. It is also necessary to explore and articulate resultant affective domains of emotions and feelings to fully understand what cynefin means to pupils in primary schools in Wales.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a small-scale grant from Association for the Study of Primary Education (ASPE), without which this research project would not have happened.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, D. 2022. “Exploring Cynefin – Being in Place. Place-based Education and the Natural World.” Holistic Education Review 2 (1): 1–6.

- Adams, D., and G. Beauchamp. 2022. “‘A Loss of ‘Cynefin’ - Losing Our Place, Losing Our Home, Losing Our Self.” Wales Journal of Education 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.16922/wje.24.1.2.

- Aldous, D., V. Evans, and D. Penney. 2022. “Curriculum Reform in Wales: Physical Education Teacher Educators’ Negotiation of Policy Positions.” The Curriculum Journal 33 (3): 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.149.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging–An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x.

- Beauchamp, G. 2017. Computing and ICT in the Primary School: From Pedagogy to Practice. 2nd ed. London: David Fulton/Routledge.

- Berger, J. H., and K. Johnston. 2015. Simple Habits for Complex Times. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Clark, A., and J. Statham. 2005. “Listening to Young Children Experts in their Own Lives.” Adoption and Fostering 29 (1): 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857590502900106.

- Cooper, L. 2017. “Lost in Translation: Exploring Childhood Identity Using Photo-elicitation.” Children's Geographies 15 (6): 625–637. http://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1284306.

- Council of Australian Governments. 2009. “Belonging, being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia.” Accessed March 15, 2023. apo.org.au.

- Crick, T., and M. Priestley. 2019. “Co-construction of a National Curriculum: The Role of Teachers as Curriculum Policy Makers in Wales.” In European Conference on Educational Research (ECER 2019).

- Demetriou, H. 2019. “More Reasons to Listen: Learning Lessons from Pupil Voice for Psychology and Education.” International Journal of Student Voice 5 (3): 1–27.

- Esteban-Guitart, M., and L. C. Moll. 2014. “Funds of Identity: A New Concept Based on the Funds of Knowledge Approach.” Culture and Psychology 20 (1): 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515934.

- Evans, G. 2022. “Back to the Future? Reflections on Three Phases of Education Policy Reform in Wales and their Implications for Teachers.” Journal of Educational Change 23 (3): 371–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09422-6.

- Ezzy, D. 2002. Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Information. London: Routledge.

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Ford, K., L. Bray, T. Water, A. Dickinson, J. Arnott, and B. Carter. 2017. “Auto-driven Photo Elicitation Interviews in Research with Children: Ethical and Practical Considerations.” Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing 40 (2): 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2016.1273977.

- French, G., G. Mckenna, T. Farrell, C. Gillic, C. Halligan, G. Lake, A. ni dhiorbhain, et al. 2022. Literature Review to Support the Updating of Aistear, the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework Commissioned by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment Education (Psychology in Education). Dublin City University. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368302986_Literature_Review_to_Support_the_Updating_of_Aistear_the_Early_Childhood_Curriculum_Framework_Literature_review_to_support_the_updating_of_Aistear_the_Early_Childhood_Curriculum_Framework_Commissioned.

- Gonzalez, N., L. Moll, and C. Amanti, eds. 2005. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. Mahwah: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Gruenewald, D. A. 2003. “Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-Conscious Education.” American Educational Research Journal 40 (3): 619–654. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003619.

- Guillemin, M., and S. Drew. 2010. “Questions of Process in Participant-generated Visual Methodologies.” Visual Studies 25 (2): 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.502676.

- Guillemin, M., and L. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity, and ‘Ethically Important Moments’ in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800403262360.

- Hackett, A. 2014. “Zigging and Zooming All Over the Place: Young Children’s Meaning Making and Movement in the Museum.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798412453730.

- Harris, A., M. Jones, and T. Crick. 2020. “Curriculum Leadership: A Critical Contributor to School and System Improvement.” School Leadership and Management 40 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1704470.

- Hogg, L., and M. Volman. 2020. “A Synthesis of Funds of Identity Research: Purposes, Tools, Pedagogical Approaches, and Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research 90 (6): 862–895. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320964205.

- Hulme, M., G. Beauchamp, and L. Clarke. 2020. “Doing Advisory Work: The Role of Expert Advisers in National Reviews of Teacher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (4): 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1580687.

- Joubert, I. 2012. “Children as Photographers: Life Experiences and the Right to be Listened to.” South African Journal of Education 32 (4): 449–464. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n4a677.

- Kahu, E., T. R. Moriarty, H. Dollery, and R. Shaw. 2022. Tūrangawaewae: Identity and Belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand. 2nd ed. Auckland: Massey University Press.

- Kurtz, C. F., and D. J. Snowden. 2003. “The New Dynamics of Strategy: Sense-making in a Complex and Complicated World.” IBM Systems Journal 42 (3): 462–483. https://doi.org/10.1147/sj.423.0462.

- Langager, M. L., and N. Spencer-Cavaliere. 2015. “‘I Feel Like This is a Good Place to be’: Children’s Experiences at a Community Recreation Centre for Children Living with low Socioeconomic Status.” Children’s Geographies 13 (6): 656–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2014.937677.

- Lipponen, L., A. Rajala, J. Hilppö, and M. Paananen. 2016. “Exploring the Foundations of Visual Methods Used in Research with Children.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (6): 936–946. http://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2015.1062663.

- Meighan, P. J. 2022. “Dùthchas, a Scottish Gaelic Methodology to Guide Self-decolonization and Conceptualize a Kincentric and Relational Approach to Community-led Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 160940692211424. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221142451.

- Ministry of Education. 2017. PISA 2015: New Zealand Students’ Wellbeing Report. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

- Murphy, J. 2013. “Place and Exile: Resource Conflicts and Sustainability in Gaelic Ireland and Scotland.” Local Environment 18 (7): 801–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.732049.

- Nowell, L., J. Norris, D. White, and N. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Oliffe, J., and J. Bottorff. 2007. “Further Than the Eye can See? Photo Elicitation and Research with Men.” Qualitative Health Research 17 (6): 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306298756.

- Pahl, K., and C. Allan. 2011. “I don’t Know What Literacy is: Uncovering Hidden Literacies in a Community Library Using Ecological and Participatory Methodologies with Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 11 (2): 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798411401864.

- Piškur, B., M. Takala, A. Berge, L. Eek-Karlsson, S. M. Ólafsdóttir, and S. Meuser. 2022. “Belonging and Participation as Portrayed in the Curriculum Guidelines of Five European Countries.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 54 (3): 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1986746.

- Pulkki, J., B. Dahlin, and V. Värri. 2017. “Environmental Education as a Lived Body Practice? A Contemplative Pedagogy Perspective.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 51 (1): 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12209.

- Rasmussen, K. 2004. “Places for Children – Children’s Places.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 11 (2): 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568204043053.

- Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. “Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006.

- Shaw, P. 2021. “Photo-elicitation and Photo-voice: Using Visual Methodological Tools to Engage with Younger Children’s Voices About Inclusion in Education.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 44 (4): 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2020.1755248.

- Sinnema, C., N. M. Nieveen, and M. Priestley. 2020. “Successful Futures, Successful Curriculum: What Can Wales Learn from International Curriculum Reforms?” The Curriculum Journal 31 (2): 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.17.

- Snowden, D. 1999. “Story Telling: An old Skill in a new Context.” Business Information Review 16 (1): 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382994237045.

- Sumsion, J., L. Harrison, K. Letsch, B. S. Bradley, and M. Stapleton. 2018. “‘Belonging’ in Australian Early Childhood Education and Care Curriculum and Quality Assurance: Opportunities and Risks.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 19 (4): 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118796239.

- Tudge, J. R., I. Mocrova, B. E. Hatfield, and R. B. Karnik. 2009. “Uses and Misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory of Development.” Journal of Family Theory and Review 1: 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x.

- Tyrie, J., and G. Beauchamp. 2018. “Children’s Perceptions of their Access to Rights in Wales: The Relevance of Gender and Age.” The International Journal of Children’s Rights 26 (4): 781–807. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02604005.

- Vander Ark, T., E. Liebtag, and N. McClennen. 2020. The Power of Place: Authentic Learning Through Place-based Education. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Vigurs, K., and H. Kara. 2017. “Participants’ Productive Disruption of a Community Photo-elicitation Project: Improvised Methodologies in Practice.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (5): 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1221259.

- Welsh Government. 2020. Guidance to Help Schools and Settings Develop their own Curriculum, Enabling Learners to Develop Towards the Four Purposes. Humanities Area of Learning and Experience (AoLE). Accessed December 11, 2022. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/humanities/designing-your-curriculum.

- Welsh Government. 2021. Welsh Government Consultation Document. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/consultations/2021-05/careers-and-work-related-experiences-consultation-document_1.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2022. Developing a Vision for Curriculum Design. Accessed November 20, 2022. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/designing-your-curriculum/developing-a-vision-for-curriculum-design.

- White, A., N. Bushin, F. Carpena-Méndez, and C. Ní Laoire. 2010. “Using Visual Methodologies to Explore Contemporary Irish Childhoods.” Qualitative Research 10 (2): 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109356735.

- Wiles, R., J. Prosser, A. Bagnoli, A. Clark, K. Davies, S. Holland, and E. Renold. 2008. “Visual Ethics: Ethical Issues in Visual Research, ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper.” Accessed April 12, 2023. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/421/.

- Williams, C. 2021. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communities, Contributions and Cynefin in the New Curriculum Working Group Final Report. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-03/black-asian-minority-ethnic-communities-contributions-cynefin-new-curriculum-working-group-final-report.pdf.

- Wilson, N., M. Minkler, S. Dasho, N. Wallerstein, and A. C. Martin. 2008. “Getting to Social Action: The Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) Project.” Health Promotion Practice 9 (4): 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289072.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2011. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. London: Sage.