ABSTRACT

This scoping review examines the prevalence of visual art participation in studies of young children’s social emotional wellbeing. Systematic reviews were identified through a search of two databases, grey literature, and reference lists. 22 reviews contained at least one study of visual art participation in children 0–9 years. Ten of these were analysed in a subset of visual art participation in children 0–5 years. The studies therein were primarily delivered by art therapists, with associated scaffolding. Other studies involved performing arts or mixed artforms. A knowledge gap has been identified which the authors will address with a systematic review.

A child with social emotional wellbeing is happy, confident, autonomous, able to maintain relationships with others, and to regulate emotions (NICE Citation2012). The ability to regulate emotions at age 2 years is associated with academic success and productivity at age 5 years (Graziano et al. Citation2007). Social and emotional wellbeing are readily present in children with secure attachment styles which develop through early interpersonal interactions (Sroufe Citation2005). The quality of the relationship a child forms towards their primary caregivers is internalised by the child as a framework on which later interpersonal interactions are modelled (Bowlby Citation1969) and is associated with the quality of their peer interaction throughout the lifespan (Doyle and Cicchetti Citation2017). This framework develops in early childhood (Opie et al. Citation2021), which means that activities can be introduced in the early years of a child’s life to improve the quality of their relationships (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and Juffer Citation2003; Wright and Edginton Citation2016). Achieving social emotional wellbeing in the early years is therefore essential for academic and social development at school.

Visual art therapy has demonstrable positive effects relating to parent–child relationships, including maternal mental health (Armstrong and Howatson Citation2015; Arroyo and Fowler Citation2013) and in dyadic attachment behaviours (Armstrong, Dalinkeviciute, and Ross Citation2019). However, a scoping review (de Witte et al. Citation2021) which identified positive factors specific to art therapy also called for empirical research into the mechanisms of change. The scaffolding provided by art therapists includes mechanisms such as the selection of appropriate art materials to reduce anxiety (de Witte et al. Citation2021) or the establishment of psychological structures such as the containment of ‘chaos’ (Hosea Citation2006, 70). This scoping review seeks to determine to what extent visual art participation has been studied as a tool for improving the attachment relationships and social emotional wellbeing of young children, and if any effect is reported without therapeutic scaffolding. The findings have implications for how the artform can be best applied in a health context (such as social prescribing, and early childhood interventions). All settings were considered, including pre-school and primary education, cultural venues, clinical settings, and homes. Relevant literature reviews were collated to identify knowledge gaps which inform the inclusion and exclusion criteria for a future systematic literature review (PROSPERO CRD42021257566).

Indicators of social emotional wellbeing were defined using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance (NICE Citation2012): as a state of happiness and confidence (emotional), emotional regulation and autonomy (psychological), and ability to maintain relationships with others (social). These indicators are reflected in a systematic review of 95 ‘well-being’ studies in young people (Szántó, Susánszky, Berényi, Sipos, and Murányi Citation2016), where commonly measured indicators included life satisfaction, happiness, self-esteem, social support, relationships with parents and peers, and social conduct. Cho and Yu (Citation2020) state the importance of selecting wellbeing indicators appropriate to the life course: early childhood is underrepresented in the literature, and therefore there is the risk of skewing data by using developmentally inappropriate indicators of wellbeing. This review seeks to examine the arts and wellbeing literature to determine if this approach to ‘childhood’ as a homogenous life phase persists.

In this review, visual art is defined as being primarily appreciated by sight, such as painting and sculpting. It excludes time-based media such as film to avoid potential overlaps with performing arts. ‘Early’ childhood is defined both as 0–8 years (Scottish Government Citation2009; UNICEF Citation2019), and 0–5 years (Department for Education Citation2021). The search therefore included any reviews with children in either age group, but excluded arts participation in adolescent populations, defined as 10–19 years (World Health Organisation Citation2022). A subset of reviews that included studies with young children 0–5 years participating in visual art was then analysed for evidence relating to social emotional wellbeing or attachment. This subset was chosen to reflect the formative period when attachment security is most malleable (Opie et al. Citation2021; Pinquart, Feußner, and Ahnert Citation2013).

The scoping review research questions were:

What do prior arts participation literature reviews address, in terms of psychological domains and population, and what common conclusions are made?

Within these reviews, how prevalent are studies that explore the effect of visual art participation with children 0–5 years old?

What proportion of the studies included in Question 2 focus on children’s social emotional wellbeing, or attachment relationships?

Method

Identifying the research question

The scoping review was conducted according to Arskey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework (Citation2005). The research questions above were identified following a period of background research conducted by the primary reviewer, in which 60 cultural policy reports and studies on the topic of arts and wellbeing were scanned for references to young children. We identified a need for a summary of artform distribution in research with this age group.

Identifying relevant studies

Relevant reviews were identified through a title, abstract and keyword search of databases, grey literature, reference lists, and hand-searching. All searches were conducted in April 2021. Firstly, the PROSPERO register of systematic review protocols was searched four times for recent or ongoing reviews, using the terms ‘arts’, ‘attachment’, ‘creativ*’ and ‘visual art’, within the ‘Child Health’ or ‘Public Health’ areas of review, added to the register before 1st April 2021. Two electronic databases were then searched for published reviews: Cochrane Database, and Scopus. A supplementary search of grey literature was conducted with the search engine Google Scholar. Finally, a hand-search of reference lists and aggregate resource sites such as the Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance (Citation2021) was conducted. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in , but in summary the review subject must examine the effects of arts participation on children’s wellbeing, attachment relationships, or other related cognitive domains. At least one study in the review must address visual art participation. This does not necessarily mean an intervention has taken place, as correlational and longitudinal studies may be considered. Participation was defined as active creative ‘making’.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The Scopus search terms were: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (art OR creativ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (wellbeing OR well-being OR attachment) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (child) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (literature OR review)). These terms were simplified in the search of Cochrane Reviews (‘art OR creativ*’ AND ‘child’) to retrieve any population-relevant material. Other considerations, such as child age, were not defined at the searching stage to ensure relevant material was not overlooked (for example with studies examining both child and adult populations). The effect of art participation on attachment relationships and social emotional wellbeing was the central research topic, but the more general term ‘wellbeing’ was included to retrieve material in related domains. ‘Health’ was not used, to exclude wellbeing studies pertaining to physical wellbeing, as defined by the World Health Organisation (Citation2020).

Study selection

Study selection was conducted by the primary reviewer. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance according to the inclusion criteria: art participation with a wellbeing outcome, an indication that a synthesis had been undertaken, and that children formed part of the population. Exclusions at this stage were titles/abstracts which did not indicate an exploration of the relationship between art participation and wellbeing, or those which were targeted at older adults or dementia patients. The selected articles were retrieved for full text appraisal. References of selected articles were hand-searched for additional studies.

‘Charting’ the data

Data were extracted on research objective(s), age of children, outcome measures, specific artforms in studies, quantity of studies, setting, publication date, search period, author’s assessment of quality, and their suggestions for future research. Following a broad overview of the characteristics of the field, which included all studies with children 9 years or younger, a further analysis was conducted on reviews that included children 0–5 years old and visual art. This subset was searched for unique studies that addressed the domains of attachment and social emotional wellbeing to assess the prevalence of this subject.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The first stage in summarising the results was to describe the characteristics of all selected reviews with children 0–9 years old. This included publication date, search period, outcome measures, author’s assessment of quality, and proportion of studies with visual art AND children 0–5 years old. This was to offer an overview of the current distribution of research in the field. The second stage was to conduct a subset analysis of reviews which included at least one study with children 0–5 years old participating in visual art, to determine what outcome measures were reported.

Results

Study selection

The PROSPERO register search returned a total of 164 records, using the terms ‘arts’ (105 records), ‘attachment’ (124 records), ‘creativ*’ (32 records) and ‘visual art’ (3 records). Only one protocol potentially addressed a similar population and activity: Verger et al. (Citation2019) focussed on pre-school children aged 2–5 years old and considered social factors such as attachment style as part of a wider search on the effect of creative interventions on resilience. However, the record had not been updated since December 2019, and did not appear to have been completed.

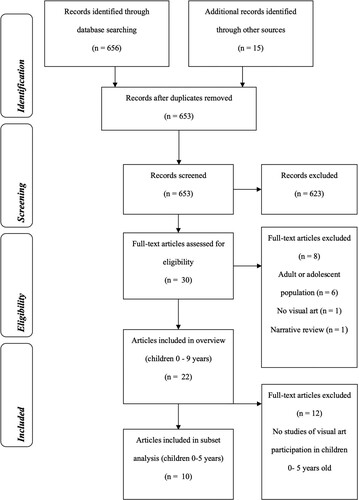

Cochrane Reviews returned 158 results of which none were relevant. Reviews commonly appeared in the results due to the term ‘ART’ as an acronym for ‘anti-retroviral therapy’ or ‘assisted reproductive technology’. Scopus returned 298 results (after excluding the term ‘reproductive’, and 13 irrelevant subject fields, such as chemistry or dentistry). After abstract screening, six reviews were retrieved for full-text appraisal. Grey literature was also searched via Google Scholar and hand-searching through reference lists of included reviews. Google Scholar returned 14,700 results, but due to the relevance ranking built into the search engine, only the first 20 pages (200 results) were considered for title and part-abstract screening. 27 reviews were retrieved for full abstract screening, and nine were retained for full-text appraisal. Finally, 15 reviews were identified through hand-searching. illustrates the search process (Moher et al. Citation2009).

In total, 30 reviews were retrieved for full-text appraisal (see Appendix Table A1), and eight were subsequently excluded (see Appendix Table A2). 22 reviews are summarised in , which all include some visual art-based studies with children 9 years old or younger. From this selection, ten reviews featured studies of the effects of visual art participation on children 0–5 years old. These reviews are summarised later in .

Table 2. Characteristics of included reviews with children 0–9 years old.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies included in subset analysis of visual art studies with children 0–5 years old (excluding pregnancy and birth interventions).

Characteristics of reviews with children 0–9 years old

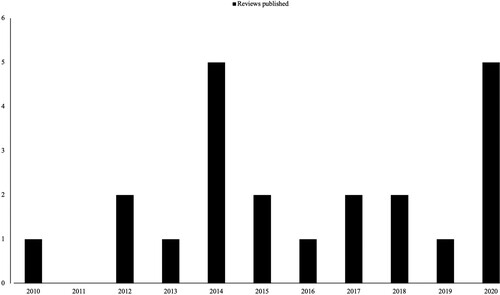

To address the first research question, all reviews which included at least one study of child visual art participation and social emotional wellbeing were assessed. All 22 reviews selected for inclusion () were published from 2010 to 2020, with two spikes in 2014 and 2020 respectively (see ). Eight reviews searched all periods, one from 1950, three from 1980s, one from 1999, three from 2000, four from 2004, one from 2010, and one did not specify a search date range. The reviews assessed 486 total studies, of which 52 studies were referred to more than once. The total number of unique references was 419. An evidence summary (APPGAHW Citation2017) was included because a literature review was conducted as part of the inquiry (Gordon-Nesbitt and Howarth Citation2020). Six reviews focussed on formal education settings, nine focussed on a clinical population (some of which were in an educational setting), and the others considered mixed settings or the general population.

As anticipated, some reviews used the term ‘health’ in addition to ‘wellbeing’, but these tended to include objective physical or mental health measures. The definition of ‘wellbeing’ included individual and social fulfilment (APPGAHW Citation2017), life-satisfaction (Mowlah et al. Citation2014), emotional wellbeing (Bungay and Vella-Burrows Citation2013; Zarobe and Bungay Citation2017), social wellbeing (Jindal-Snape, Scott, and Davies Citation2014), physical wellbeing (Toma et al. Citation2014), and the physical, mental and social facets of health defined by the World Health Organisation (Fancourt and Finn Citation2019).

20 of the reviews described significant methodological problems with the studies surveyed. The exception was the leisure participation review (Dahan-Oliel, Shikako-Thomas, and Majnemer Citation2012), but only one of the studies was art-based. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Inquiry Report (Citation2017) was uncritical of the evidence presented in the relevant chapters (6.1-3), having applied a quality assessment framework in the selection process (Gordon-Nesbitt and Howarth Citation2020), but discussed a general need for arts and health projects to move away from the historical use of anecdotal ‘evidence’. Common limitations identified in the other reviews were small sample sizes, researcher bias, lack of longitudinal research or follow-up data, lack of transparent methodology or definitions, inconsistent use of measurement tools, mixed artforms, no randomisation, and lack of controls. In general, it was difficult to attribute causation.

Ten reviews directly discussed either the lack of comparison between the effects of different artforms, or the lack of detailed descriptions of the arts intervention to enable such a comparison to be made (Bungay and Vella-Burrows Citation2013; Callinan and Coyne Citation2020; Derman and Deatrick Citation2016; Jindal-Snape, Scott, and Davies Citation2014; Citation2018; Menzer Citation2015; Slayton, D'Archer, and Kaplan Citation2010; Toma et al. Citation2014; van Westrhenen and Fritz Citation2014; Zarobe and Bungay Citation2017). McDonald and Drey (Citation2018) state that interventions were described in ‘varying degrees of detail’ (Citation2018, 39), which suggests it is difficult to synthesise results. Some reviews considered mixed arts interventions (such as storytelling or music within art therapy sessions) with no indication that separation of artforms might be necessary to attribute effects to specific mechanisms (e.g. APPGAHW Citation2017; Moula Citation2020; Moula et al. Citation2020; Citation2014). These were either broad cultural policy reports or focussed on therapeutic interventions. The review of visual art therapy interventions within paediatric cancer settings (Derman and Deatrick Citation2016) specifically discussed the heterogeneity of interventions, which included both group and individual sessions, and structured and free art-making sessions. Whilst each study was rated ‘good’ or ‘high’ quality in their literature review, it proved difficult to compare approaches. The authors suggest implementing standardised art interventions in future studies. Menzer (Citation2015) suggests that for better understanding of the effects of art participation not only should artforms be separated, but art activity should also be separated from the social context, such as participation within a group.

To address the second research question, only 35 (8.4%) of the 419 unique studies in the reviews included children 0–5 years old participating in visual art (see subset analysis below). Menzer (Citation2015) also concludes that not much research exists on the effect of visual art participation among infants and toddlers. Art therapy interventions are the exception (e.g. Armstrong and Ross Citation2020). Infants and toddlers in the general, non-clinical population predominantly appear in studies of performing arts, such as music (e.g. Fancourt and Finn Citation2019; Jindal-Snape, Scott, and Davies Citation2014).

Subset analysis of studies with children 0–5 years old

The ten reviews that included studies with children 0–5 years old and visual art (see ) included 35 unique references relevant to this subset, as discussed. One study was published in 1993, and the others between 2000 and 2019. These studies will now be described to address our third research question regarding the proportion that focus on children’s social emotional wellbeing or attachment relationships.

Only two reviews (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020; Menzer Citation2015), specifically collated evidence on the effect of visual art participation on children’s relational experiences (15 studies on parent–child relationships and social emotional development respectively). To characterise the studies in the other eight reviews (see ), two studies focussed on parental mental health and wellbeing (Ponteri Citation2001; White et al. Citation2010), and two studies on child emotional regulation (Ball Citation2002; Brown and Sax Citation2013). The other studies did not address the domains in our third review question (attachment or social emotional wellbeing). Instead, they included: coping mechanisms and mood in a hospital context (Councill Citation1993; Favara-Scacco et al. Citation2001; Madden et al. Citation2010; Massimo and Zarri Citation2006; Siegel et al. Citation2016; Soanes et al. Citation2009), art as expression of grief or trauma (Chilcote Citation2007; DiSunno, Linton, and Bowes Citation2011; Hanney and Kozlowska Citation2002; Howie et al. Citation2002; Klorer Citation2005; Kozlowska and Hanney Citation2001), academic or learning skills (Brown, Benedett, and Armistead Citation2010; Martin Citation2009), and behavioural problems (Kearns Citation2004; Saunders and Saunders Citation2000).

Of the 15 studies which addressed parent–child relationships, reviewed by Armstrong and Ross (Citation2020) and Menzer (Citation2015), all but two were conducted by art therapists. The two other studies were a project delivered by visual artists, in partnership with a mental health trust (Black et al. Citation2015), and a cohort study in which the only visual art component was ‘block building’ (Muñiz, Silver, and Stein Citation2014). This was one aspect of a wider ‘play’ category and is therefore not isolated clearly enough for the purposes of this review.

The authors of the two most relevant reviews concluded that data was limited by sample size and lack of control groups (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020), and by unstandardised measurement tools (Menzer Citation2015). However, positive wellbeing changes were identified in parents, and improvements in parent–child relationships following visual art participation (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020). Menzer (Citation2015) concludes that arts participation in general benefits social emotional development in the short-term but as most of the studies focussed on intrinsically social arts activities (such as parent–child or group activities) the effects of art participation itself were difficult to isolate.

Discussion

‘Wellbeing’ encompassed various domains in the 22 reviews, including fulfilment, life satisfaction, and social, emotional and physical wellbeing. Only one review exclusively considered the impact of visual art making on young children’s attachment relationships or social emotional wellbeing (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020). This scarcity of published evidence does not reflect the volume of work on clinical attachment interventions (e.g. Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and Juffer Citation2003), but may reflect child wellbeing studies in general. Cho and Yu (Citation2020) found that only four of 186 child wellbeing studies focussed exclusively on children 0–5 years old. Pollard and Lee (Citation2003) argue that younger children’s wellbeing is at risk of being under-reported as there were a greater number of wellbeing indicators used in studies with older children. This may indicate a lack of appropriate tools to capture the experience of very young children. In a rights-based approach to wellbeing, where children have the right to have their views heard (Convention on the Rights of the Child Citation1989), subjective measures allow children to offer their own perspective and be treated as an active entity within a family. This is more difficult when children are pre-verbal, and requires wider adoption of infant-focussed observational tools (e.g. Armstrong and Ross Citation2021).

Art therapists facilitated most of the relevant studies in the reviews. As discussed in the introduction, the scaffolding provided by art therapists involves several potential mechanisms of change (de Witte et al. Citation2021; Hosea Citation2006), which may confound the intrinsic effects of art making. This has implications for the scale of benefits achievable in public or pre-school art settings without therapeutic guidance. However, Armstrong and Ross (Citation2020) found potential properties which could potentially be isolated from therapeutic processes in future research, including the production of physical artworks. de Witte et al. (Citation2021) similarly isolate the ‘artistic product’ (as a mechanism for transference), as a visual art-specific factor in comparison to other creative arts therapies. The production and display of physical artworks offer a means of reflection, whether taken home, or displayed in a group setting (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020). Encouraging parents to recognise and support their young child’s interests in the activity, by providing developmentally appropriate art materials and the means to regulate ‘mess’ may support emotional regulation (Armstrong and Ross Citation2020). This, as discussed, is associated with academic productivity (Graziano et al. Citation2007).

Most studies in the age group were in performing arts or mixed artforms. This is an important distinction because performing artforms involve different physical properties to visual art making, such as vocalisation and movement. These have unique physiological, neurological and hormonal effects. For example, music participation and listening decrease cortisol levels (Fancourt, Ockelford, and Belai Citation2014), and even a comparison between music and drama participation found different effects on children’s social skills (Schellenberg Citation2004). UK health advisory bodies recommend dyadic visual arts participation to develop positive attachment behaviour (NHS Education for Scotland Citation2016), bonding, and perinatal mental health (APPGAHW Citation2017), but there must be clear evidence to support these recommendations. Without further robust research, it is difficult to advocate for the social emotional wellbeing benefits of participation in visual art compared to performing arts, despite promising evidence in art therapy. Only one study reviewed by Armstrong and Ross (Citation2020) was delivered by practicing visual artists (Black et al. Citation2015), which suggests that there may be a benefit to the field if training was widely adopted by artist-educators on supporting early childhood social emotional wellbeing.

This scoping review was limited by the number of databases searched. However, the hand-searching was thorough, and the search terms were inclusive of all artforms and child age. The specific population area could then be explored in the knowledge that cross-age reviews had not been excluded.

Conclusion

In the initial selection of 22 reviews which included children 0–9 years old, the majority concluded that there were significant methodological problems in the field, and that inconsistencies in design, measures, and reporting made the synthesis of evidence very difficult. Only 8.4% of studies represented in the 22 selected reviews included visual art participation with children 0–5 years old. These studies were found in ten reviews from the initial selection, two of which addressed the effects of visual art participation on the social emotional wellbeing of young children. The other eight addressed different aspects of wellbeing, such as emotional regulation and coping mechanisms in hospitalised children. Only Armstrong and Ross (Citation2020) addressed the target population, visual art activity, and parent–child relationships, and found some evidence to suggest that there are mechanisms of change unique to visual art. Menzer’s review (Citation2015) focussed on social emotional development in children 0–8 years, in all artforms. There is therefore a knowledge gap regarding the effect on the social emotional wellbeing of young children participating in visual art. In addition, relevant studies in these two reviews were primarily conducted in a therapeutic context, and the remaining studies utilised mixed artforms. The heterogeneity of artforms was identified as a problem in almost half of all reviews. Therefore, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding effects attributable to visual art making as distinct from the confounding factors of therapeutic scaffolding or mixed artforms.

The authors have registered a protocol (PROSPERO CRD42021257566) for a mixed methods systematic review to address the knowledge gaps identified. This scoping review also forms a rationale for researchers to conduct controlled studies with preschool children, perhaps within a visual art organisation, to assess the effect of parent–child art participation in a non-therapeutic setting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- APPGAHW (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing). 2017. Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. Inquiry report, 2nd ed. London. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/.

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O'Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Armstrong, Victoria Gray, Egle Dalinkeviciute, and Josephine Ross. 2019. “A Dyadic Art Psychotherapy Group for Parents and Infants: Piloting Quantitative Methodologies for Evaluation.” International Journal of Art Therapy 24 (3): 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1590432.

- Armstrong, Victoria Gray, and Rosie Howatson. 2015. “Parent-Infant Art Psychotherapy: A Creative Dyadic Approach to Early Intervention.” Infant Mental Health Journal 36 (2): 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21504.

- Armstrong, Victoria Gray, and Josephine Ross. 2020. “The Evidence Base for Art Therapy with Parent and Infant Dyads: An Integrative Literature Review.” International Journal of Art Therapy 25 (3): 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1724165.

- Armstrong, Victoria Gray, and Josephine Ross. 2021. “Observational Tool for Infant-Caregiver Activities and Therapeutic Interventions. Dundee: University of Dundee. https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/en/publications/observational-tool-for-infant-caregiver-activities-and-therapeuti.

- Arroyo, Carl, and Neil Fowler. 2013. “Before and After: A Mother and Infant Painting Group.” International Journal of Art Therapy 18 (3): 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.844183.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian J., Marinus H. van IJzendoorn, and Femmie Juffer. 2003. “Less is More: Meta-Analyses of Sensitivity and Attachment Interventions in Early Childhood.” Psychological Bulletin 129 (2): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195.

- Ball, Barbara. 2002. “Moments of Change in the Art Therapy Process.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 29 (2): 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(02)00138-7.

- Black, Carrie-Ann, Megan Ellis, Lucy Harris, Alison Rooke, Imogen Slater, and Laura Cuch. 2015. Making it Together: An Evaluative Study of Creative Families an Arts and Mental Health Partnership Between the South London Gallery and the Parental Mental Health Team. London: South London Gallery and the Southwark Mental Health Family Strategy Group. https://www.southlondongallery.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Creative_Families_Report_b_0.pdf.

- Bosgraaf, Liesbeth, Marinus Spreen, Kim Pattiselanno, and Susan van Hooren. 2020. “Art Therapy for Psychosocial Problems in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Narrative Review on Art Therapeutic Means and Forms of Expression, Therapist Behavior, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 584685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584685.

- Bowlby, John. 1969. Attachment and Loss: Volume I: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Brown, Eleanor D., Barbara Benedett, and M. Elizabeth Armistead. 2010. “Arts Enrichment and School Readiness for Children at Risk.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25 (1): 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.07.008.

- Brown, Eleanor D., and Kacey L. Sax. 2013. “Arts Enrichment and Preschool Emotions for Low-Income Children at Risk.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 28 (2): 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.08.002.

- Bungay, Hilary, and Trish Vella-Burrows. 2013. “The Effects of Participating in Creative Activities on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People: A Rapid Review of the Literature.” Perspectives in Public Health 133 (1): 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913912466946.

- Callinan, J., and I. Coyne. 2020. “Arts-Based Interventions to Promote Transition Outcomes for Young People with Long-Term Conditions: A Review.” Chronic Illness 16 (1): 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395318782370.

- Chilcote, Rebekah L. 2007. “Art Therapy with Child Tsunami Survivors in Sri Lanka.” Art Therapy 24 (4): 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129475.

- Cho, Esther Yin-Nei, and Fuk-Yuen Yu. 2020. “A Review of Measurement Tools for Child Wellbeing.” Children and Youth Services Review 119: 105576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105576.

- Colegrove, Vivienne M., and Sophie S. Havighurst. 2017. “Review of Nonverbal Communication in Parent–Child Relationships: Assessment and Intervention.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 26 (2): 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0563-x.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. “Treaty no. 27531.” In United Nations Treaty Series, 1577, 3–178. Geneva: United Nations. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf.

- Councill, Tracy. 1993. “Art Therapy with Pediatric Cancer Patients: Helping Normal Children Cope with Abnormal Circumstances.” Art Therapy Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 10 (2): 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1993.10758986.

- Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance. 2021. “Research and Evaluation”. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/resources/research-and-evaluation.

- Dahan-Oliel, Noemi, Keiko Shikako-Thomas, and Annette Majnemer. 2012. “Quality of Life and Leisure Participation in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities: A Thematic Analysis of the Literature.” Quality of Life Research 21 (3): 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0063-9.

- Daykin, Norma, Ellie Byrne, Tony Soteriou, and Susan O'Connor. 2008. “Review: The Impact of Art, Design and Environment in Mental Healthcare: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 128 (2): 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424007087806.

- Department for Education. 2021. Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework–2.

- Derman, Yael E., and Janet A. Deatrick. 2016. “Promotion of Well-Being During Treatment for Childhood Cancer.” Cancer Nursing 39 (6): E1–E16. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000318.

- de Witte, Martina, Hod Orkibi, Rebecca Zarate, Vicky Karkou, Nisha Sajnani, Bani Malhotra, Rainbow Tin Hung Ho, Girija Kaimal, Felicity A. Baker, and Sabine C. Koch. 2021. “From Therapeutic Factors to Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies: A Scoping Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 678397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397.

- DiSunno, Rebecca, Kristin Linton, and Elissa Bowes. 2011. “World Trade Center Tragedy: Concomitant Healing in Traumatic Grief Through Art Therapy with Children.” Traumatology 17 (3): 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765611421964.

- Doyle, Colleen, and Dante Cicchetti. 2017. “From the Cradle to the Grave: The Effect of Adverse Caregiving Environments on Attachment and Relationships Throughout the Lifespan.” Clinical Psychology: a publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association 24 (2): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12192.

- Fancourt, Daisy, and Saoirse Finn. 2019. “What is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review. Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report 67.” Copenhagen: World Health Organisation. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553773/.

- Fancourt, Daisy, Adam Ockelford, and Abi Belai. 2014. “The Psychoneuroimmunological Effects of Music: A Systematic Review and a New Model.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 36: 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.014.

- Favara-Scacco, Cinzia, Guiseppina Smirne, Gino Schilir, and Andrea Di Cataldo. 2001. “Art Therapy as Support for Children with Leukemia During Painful Procedures.” Medical and Pediatric Oncology 36 (4): 474–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpo.1112.

- Galloway, Susan. 2007. “Cultural Participation and Individual Quality of Life: A Review of Research Findings.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 1 (3-4): 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-007-9024-4.

- Gordon-Nesbitt, Rebecca, and Alan Howarth. 2020. “The Arts and the Social Determinants of Health: Findings from an Inquiry Conducted by the United Kingdom All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing.” Arts & Health 12 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2019.1567563.

- Graziano, Paulo A., Rachael D. Reavis, Susan P. Keane, and Susan D. Calkins. 2007. “The Role of Emotion Regulation in Children's Early Academic Success.” Journal of School Psychology 45 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002.

- Hall, Penelope. 2008. “Painting Together: An Art Therapy Approach to Mother-Infant Relationships.” In In Art Therapy with Children: From Infancy to Adolescence, edited by Caroline Case and Tessa Dalley, 20–35. London: Routledge.

- Hanney, Lesley, and Kasia Kozlowska. 2002. “Healing Traumatized Children: Creating Illustrated Storybooks in Family Therapy.” Family Process 41 (1): 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000037.x.

- Hogan, Susan, David Sheffield, and Amelia Woodward. 2017. “The Value of Art Therapy in Antenatal and Postnatal Care: A Brief Literature Review with Recommendations for Future Research.” International Journal of Art Therapy 22 (4): 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1299774.

- Hosea, Hilary. 2006. “The Brush’s Footmarks: Parents and Infants Paint Together in a Small Community Art Therapy Group.” International Journal of Art Therapy 11 (2): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830600980317.

- Hosea, Hilary. 2011. “The Brush’s Foot Marks: Researching a Small Community Art Therapy Group.” In In Art Therapy Research in Practice, edited by Andrea Gilroy, 61–80. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Hosea, Hilary. 2017. “Amazing Mess: Mothers Get in Touch with Their Infants Through the Vitality of Painting Together.” In In Art Therapy in The Early Years: Therapeutic Interventions with Infants, Toddlers and Their Families, edited by Julia Meyerowitz-Katz and Dean Reddick, 104–117. London: Routledge.

- Howie, Paula, Berre Burch, Selby Conrad, and Shari Shambaugh. 2002. “Releasing Trapped Images: Children Grapple with the Reality of the September 11 Attacks.” Art Therapy 19 (3): 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2002.10129401.

- Jindal-Snape, Divya, Dan Davies, Rosalind Scott, Anna Robb, Chris Murray, and Chris Harkins. 2018. “Impact of Arts Participation on Children's Achievement: A Systematic Literature Review.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 29 (2018): 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.06.003.

- Jindal-Snape, Divya, Rosalind Scott, and Dan Davies. 2014. “‘Arts and Smarts’: Assessing the Impact of Arts Participation on Academic Performance During School Years. Systematic Literature Review (Work Package 2).” Glasgow Centre for Population Health. http://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/4512/GCPH__Arts_and_Smarts__Sys_Review_WP2.pdf.

- Kearns, Diane. 2004. “Art Therapy with a Child Experiencing Sensory Integration Difficulty.” Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 21 (2): 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129551.

- Klorer, P. Gussie. 2005. “Expressive Therapy with Severely Maltreated Children: Neuroscience Contributions.” Art Therapy 22 (4): 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129523.

- Kozlowska, Kasia, and Lesley Hanney. 2001. “An Art Therapy Group for Children Traumatized by Parental Violence and Separation.” Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 6 (1): 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104501006001006.

- Lavey-Khan, Shona, and Dean Reddick. 2018. “Painting Together: A Dyadic Art Therapy Group.” Unpublished manuscript. Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation and Islington Council Early Years Education.

- Leckey, Jill. 2011. “The Therapeutic Effectiveness of Creative Activities on Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 18 (6): 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01693.x.

- Leenarts, Laura E.W., Julia Diehle, Theo A.H. Doreleijers, Elise P. Jansma, and Ramón J.L. Lindauer. 2013. “Evidence-Based Treatments for Children with Trauma-Related Psychopathology as a Result of Childhood Maltreatment: A Systematic Review.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 22 (5): 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0367-5.

- Madden, Jennifer R., Patricia Mowry, Dexiang Gao, Patsy McGuire Cullen, and Nicholas K. Foreman. 2010. “Creative Arts Therapy Improves Quality of Life for Pediatric Brain Tumor Patients Receiving Outpatient Chemotherapy.” Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 27 (3): 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454209355452.

- Martin, Nicole. 2009. Art as an Early Intervention Tool for Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Massimo, Luisa M., and Daniela A. Zarri. 2006. “In Tribute to Luigi Castagnetta-Drawings. A Narrative Approach for Children with Cancer.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1089 (1): xvi–xxiii. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1386.020.

- McDonald, Alex, and Nicholas StJ Drey. 2018. “Primary-School-Based Art Therapy: A Review of Controlled Studies.” International Journal of Art Therapy 23 (1): 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1338741.

- Menzer, Melissa. 2015. The Arts in Early Childhood: Social and Emotional Benefits of Arts Participation. A Literature Review and Gap-Analysis (2000-2015). Washington: National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/arts-in-early-childhood-dec2015-rev.pdf.

- Meyerowitz-Katz, Julia. 2017. “The Crisis of the Cream Cakes: An Infant’s Food Refusal as a Representation of Intergenerational Trauma.” In In Art Therapy in The Early Years: Therapeutic Interventions with Infants, Toddlers and Their Families, edited by Julia Meyerowitz-Katz and Dean Reddick, 118–132. London: Routledge.

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and the PRISMA Group. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

- Moula, Zoe. 2020. “A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Art Therapy Delivered in School-Based Settings to Children Aged 5-12 Years.” International Journal of Art Therapy 25 (2): 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1751219.

- Moula, Zoe, Supritha Aithal, Vicky Karkou, and Joanne Powell. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Child-Focused Outcomes and Assessments of Arts Therapies Delivered in Primary Mainstream Schools.” Children and Youth Services Review 112: 104928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104928.

- Mowlah, Andrew, Vivien Niblett, Jonathon Blackburn, and Marie Harris. 2014. The Value of Arts and Culture to People and Society: An Evidence Review. Manchester: Arts Council England. https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/docs/the-value-of-arts-and-culture-to-people-and-society/.

- Muñiz, Elisa I., Ellen J. Silver, and Ruth E.K. Stein. 2014. “Family Routines and Social-Emotional School Readiness Among Preschool-Age Children.” Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 35 (2): 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000021.

- NHS Education for Scotland (National Health Service Education for Scotland). 2016. Infant Mental Health: Developing Positive Early Attachments. https://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/media/x4lmfskd/final_imh_interactive_pdf__3_.pdf.

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). 2012. Social and Emotional Wellbeing: Early Years (PH40). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph40.

- Opie, Jessica E., Jennifer E. McIntosh, Timothy B. Esler, Robbie Duschinsky, Carol George, Allan Schore, Emily J. Kothe, Evelyn S. Tan, Christopher J. Greenwood, and Craig A. Olsson. 2021. “Early Childhood Attachment Stability and Change: A Meta-Analysis.” Attachment & Human Development 23 (6): 897–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1800769.

- Parashak, Sharyl Thode. 2008. “Object Relations and Attachment Theory: Creativity of Mother and Child in the Single Parent Family.” In In Family Art Therapy: Foundations of Theory and Practice, edited by Christine Kerr and Janice Hoshino, 65–93. New York: Routledge.

- Perruzza, Nadia, and Elizabeth Anne Kinsella. 2010. “Creative Arts Occupations in Therapeutic Practice: A Review of the Literature.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 73 (6): 261–268. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925468943.

- Pinquart, Martin, Christina Feußner, and Lieselotte Ahnert. 2013. “Meta-Analytic Evidence for Stability in Attachments from Infancy to Early Adulthood.” Attachment & Human Development 15 (2): 189–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.746257.

- Pollard, Elizabeth L., and Patrice D. Lee. 2003. “Child Well-Being: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Social Indicators Research 61 (1): 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021284215801.

- Ponteri, Amy K. 2001. “The Effects of Group Art Therapy on Depressed Mothers and their Children.” Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 18 (3): 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2001.10129729.

- Proulx, Lucille. 2000. “Container, Contained, Containment: Group Art Therapy with Toddlers 18 to 30 Months and their Parent.” Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal 14 (1): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2000.11432243.

- Proulx, Lucille. 2002. “Strengthening Ties, Parent-Child-Dyad: Group Art Therapy with Toddlers and Parents.” American Journal of Art Therapy 40 (4): 238–258.

- Proulx, Lucille. 2003. Strengthening Emotional Ties Through Parent-Child Dyad Art Therapy: Interventions with Infants and Pre-Schoolers. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Saunders, Edward J., and Jeanne A. Saunders. 2000. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Art Therapy Through a Quantitative, Outcomes-Focused Study.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 27 (2): 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00041-6.

- Schellenberg, E. Glenn. 2004. “Music Lessons Enhance IQ.” Psychological Science 15 (8): 511–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00711.x.

- Schweizer, Celine, Eric J. Knorth, and Marinus Spreen. 2014. “Art Therapy with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Clinical Case Descriptions on ‘What Works’.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 41 (5): 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.009.

- Scottish Government. 2009. Early Years Framework. https://www.gov.scot/publications/early-years-framework/pages/1/.

- Siegel, Jane, Haruka Iida, Kenneth Rachlin, and Garret Yount. 2016. “Expressive Arts Therapy with Hospitalized Children: A Pilot Study of Co-Creating Healing Sock Creatures©.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 31 (1): 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2015.08.006.

- Slayton, Sarah C., Jeanne D'Archer, and Frances Kaplan. 2010. “Outcome Studies on the Efficacy of Art Therapy: A Review of Findings.” Art Therapy 27 (3): 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2010.10129660.

- Soanes, Louise, Darren Hargrave, Lauren Smith, and Faith Gibson. 2009. “What are the Experiences of the Child with a Brain Tumour and Their Parents?” European Journal of Oncology Nursing 13 (4): 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2009.03.009.

- Sroufe, L. Alan. 2005. “Attachment and Development: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study from Birth to Adulthood.” Attachment & Human Development 7 (4): 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928.

- Szanto, Zsuzsa, Eva Susanszky, Zoltan Berenyi, Florian Sipos, and Istvan Muranyi. 2016. “Understanding Well-Being. Review of European Literature 1995-2014.” Journal of Social Research & Policy 7 (1): 57–75.

- Toma, Madalina, Jacqui Morris, Chris Kelly, and Divya Jindal-Snape. 2014. “The Impact of Art Attendance and Participation on Health and Wellbeing: Systematic Literature Review (Work Package 1).” Glasgow Centre for Population Health. http://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/4511/GCPH_Art_and_Health_Sys_Review_WP1.pdf.

- Tomlinson, Alan, Jack Lane, Guy Julier, Lily Grigsby Duffy, Annette Payne, Louise Mansfield, Tess Kay, et al. 2018. “A Systematic Review of the Subjective Wellbeing Outcomes of Engaging with Visual Arts for Adults (“Working-Age”, 15-64 Years) with Diagnosed Mental Health Conditions.” What Works Centre for Wellbeing. https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/visual-art-and-mental-health/.

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). 2019. “The Formative Years: UNICEF’s Work on Measuring Early Childhood Development.” https://data.unicef.org/resources/the-formative-years-unicefs-work-on-measuring-ecd/.

- Urquhart, Melissa, Fiona Gardner, Margarita Frederico, and Rachael Sanders. 2020. “Right Brain to Right Brain Therapy: How Tactile, Expressive Arts Therapy Emulates Attachment.” Children Australia 45 (2): 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2020.30.

- Uttley, Lesley, Alison Scope, Matt Stevenson, Andrew Rawdin, Elizabeth Taylor Buck, Anthea Sutton, John Stevens, Eva Kaltenthaler, Kim Dent-Brown, and Chris Wood. 2015. “Systematic Review and Economic Modelling of the Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Art Therapy Among People with Non-Psychotic Mental Health Disorders.” Health Technology Assessment 19 (18): 1–120. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19180.

- van Westrhenen, Nadine, and Elzette Fritz. 2014. “Creative Arts Therapy as Treatment for Child Trauma: An Overview.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 41 (5): 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.004.

- Verger, Nicolas, Kareena McAloney-Kocaman, Julie Thomson, and Julie Guiller. 2019. A Systematic Review of Creativity-Based Interventions to Foster Resilience in Preschool Children.” PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019160848. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID = CRD42019160848.

- White, Madeleine P., Steven Anderson, Kirsty E. Stansfield, and Barbara Gulliver. 2010. “Parental Participation in a Visual Arts Programme on a Neonatal Unit.” Creativity in Health 6 (5): 165–169.

- World Health Organisation. 2020. Basic Documents: Forty-Ninth Edition (Including Amendments Adopted up to 31 May 2019). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organisation. 2022. Adolescent Data. Geneva: World Health Organisation. https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/adolescent-data.

- Wright, Barry, and Elizabeth Edginton. 2016. “Evidence-Based Parenting Interventions to Promote Secure Attachment: Findings From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Global Pediatric Health 3: 2333794X–16661888. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X16661888.

- Zarobe, Leyre, and Hilary Bungay. 2017. “The Role of Arts Activities in Developing Resilience and Mental Wellbeing in Children and Young People a Rapid Review of the Literature.” Perspectives in Public Health 137 (6): 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913917712283.

Appendix

Table A1. Reviews selected for full-text appraisal.

Table A2. Reviews excluded at full text appraisal stage.