ABSTRACT

Differentiation is a major challenge within education. To explore the beliefs and attitudes of Pre-Service Teachers (PSTs) towards differentiation, an interpretivist methodology was deployed with PSTs working through a Professional Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) within Scotland. Unstructured focus group interviews were conducted and elements of grounded theory and thematic analysis were used for data analysis. From the data, PSTs shared a willingness to differentiate to work towards making teaching and learning accessible for all. However, the three most significant negative themes generated demonstrate tensions PSTs encounter with differentiation: the role of ‘ability’; pressure and stress; and conflicting messages.

To support diversity in heterogeneous classrooms, differentiation has, over the last 40 years, become commonplace theoretically and practically (Hamilton and O’Hara Citation2011; Graham et al. Citation2021; GTCS, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Frequently, it links to inclusion (Cremin and Arthur Citation2014, 276) according to Articles 28 and 29 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN Citation1989) to affirm that all children, without discrimination, have the right to an appropriate education which concurs with societal and educational expansion to increase the number of children, historically educated separately, within ‘mainstream’ schools (Chopra Citation2008).

While perceived student ability traditionally dominates differentiation theory, the practice has developed significantly. The 1994 Salamanca Statement consolidated ‘mainstreaming’ stating that children commonly labelled ASN (Additional Support Needs), SEN (Special Educational Needs) or LD (Learning Difficulties) should be educated alongside ‘mainstream peers’ to better ensure the active engagement of all in a wider society (Monsen, Ewing, and Kwoka Citation2014; UNESCO Citation1994). Differentiation neither ‘just happens’ nor is ‘innate’; it must be learnt and developed. As with other professional aspects, teacher beliefs, attitudes and values significantly influence differentiation views and practice. Although commonly linked to inclusion for all, for many teachers, students and qualified alike, differentiation is professionally taxing.

This paper examines instances in the development of pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) beliefs and attitudes about differentiation in the context of a partnership-focused initial teacher education (ITE) course by focusing on connections between student university and placement experiences. To start, we assume that avowed intentions and aims for differentiation and its support in Scottish schools, mark it out as ‘good professional practice’. Importantly, achieving equity for all is a priority within Scotland’s National Improvement Framework (NIF) which seeks to ensure that ‘ … every child has the same opportunity to succeed’ (Scottish Government Citation2023a, 2). This paper’s originality lies in its focus on the development of PST beliefs about differentiation in situ rather than the activities with which they engaged. We examine their beliefs and experiences, rather than the actual activities by which they attempted to differentiate. In this regard, the work’s originality lies in its consideration of differentiation positioning, rather than differentiation enactment.

The paper is in three parts. First, it examines differentiation generally, followed by a discussion of the Scottish policy context and relationships with initial teacher education (ITE). Second, it analyses focus group data with ITE students on a one-year Professional Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) at a Scottish university during the academic year 2018/2019. Finally, the paper concludes by detailing possible ways differentiation might feature in ITE to engender positive PST beliefs; policy implications are thus foregrounded.

Differentiation and inclusive education

Within an inclusive education framework, differentiation is positioned as a professionally attainable, learner-centred approach. Focused on the provision of different and appropriate material, approaches, outcomes or tasks, differentiation concerns professional matters such as duty, care and education for all. However, over the last four decades, differentiation has been reported as the most difficult professional aspect, particularly for PSTs (Varcoe and Boyle Citation2014; Veenman Citation1984). Adopting the premise that teaching quality is an amalgam of ‘doing’, ‘knowing’ and ‘identifying' teaching (Adams and McLennan Citation2021), underscores that PST beliefs are relevant to embed differentiation within professional practice. For PSTs to engage in high-quality differentiation, they must examine personal perspectives and experiences, and for these to be acknowledged by ITE-tutors.

Differentiation has issues: attempts to provide for heterogeneous pupil needs present PSTs and experienced professionals with tensions theoretically, ethically, conceptually and practically. As a marker of inclusive practice, differentiation is a broad church and consequently, some argue for a return to ‘special education’, ‘streaming’ or ‘setting’ as mechanisms to meet learner-need and craft ‘workable’ environments. Arguments originate differently but seem centred either on the belief that meeting everyone’s needs is too difficult in busy classrooms (Tomlinson and Imbeau Citation2012) or that learners learn best when working with those of similar ‘abilities’ (Hamilton and O’Hara Citation2011).

Graham et al. (Citation2021) highlight definitional inconsistency which may result in myriad differentiation practices. Associated are two dominant inclusive perspectives: rights-respecting-based versus needs-based. From the former, concerns emerge that differentiation by content and task may pre-determine and limit children’s learning (Hart, Drummond, and Mcintyre Citation2013) and positionality. Conversely, practices in a needs-based approach give children different learning experiences, thus ensuring support and challenge for all (Tomlinson Citation2017). Differentiation by setting and/or streaming may be viewed as a form of segregation (Graham et al. Citation2021). Importantly, teaching or learning can often highlight differing inclusion perspectives.

Differentiation by student ‘ability’ is common across Scottish schools (Education Scotland Citation2015; Hamilton and O’Hara Citation2011); accordingly to develop differentiation practice, the Donaldson Report (Citation2011) called for systematic change in ITE and highlighted the role differentiation plays in PST development. Donaldson’s developments challenged traditional notions of pupil ability or intelligence and focused on wider professional understanding, such as how socio-economic background can and does influence learning. Furthermore, How Good Is Our School 4 (Education Scotland (ES) Citation2015) a school self-evaluation tool, sets inclusive, equality and equity expectations for all learners (quality indicators 3.1 and 3.2).

Differentiation and practice

To plan differentiated teaching is an explicit expectation of the GTCS for provisional and full teacher registration across Scotland (GTCS Citation2021a, standard 3.1.1). The professional action of differentiation has previously been highlighted as a major theme of challenge for novice and experienced teachers (Varcoe and Boyle Citation2014; Veenman Citation1984). Furthermore, anecdotal evidence from interactions between one of the authors here and PSTs elevates that the most difficulty expressed by PSTs over several years in Scotland has been how to differentiate to meet the academic needs of all children within the diverse classroom. Against this backdrop, the research here presented shifts in discussions about PST differentiation skills and knowledge, of PST beliefs about differentiation as a precursor to developing actionable skills.

Even though Wan (Citation2017) cites differentiation as one of the most effective tools to progress pupil learning and despite Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) view that differentiation should be based on the belief that all can varyingly succeed, accord does not exist. We argued above that differentiation seeks to meet the needs of predefined groups (for example, the ‘less able’) via task, outcome or support variations (Cremin and Arthur Citation2014; Pollard et al. Citation2014). This technical perspective originates from a desire to meet the needs of pre-defined ‘homogeneous sub-groups’: teachers offer provisions differentially matched to the assumption and presumption of pupil ‘need’. This relies on the appropriate identification of heterogeneous ‘need’ augmented through ‘homogeneous sub-groups’, and the application of practical methods to meet such observations.

Historically, ‘need’ centred on the application of perceptions of ‘ability’ or ‘intelligence’ and the provision of matched tasks through sorting pupils into ‘ability groups’. At the end of the twentieth century, there was an effort to expand conceptions of need through Multiple Intelligence Theory (Gardner Citation1983) or ‘learning styles’ but these seem now not to pervade educational research or practice. These challenged historical ideas of ability and/or intelligence, so disrupting simplistic interpretations of links between within-person attributes and educational provision. These movements supported the position that differentiation is the expression of value positions concerning a place for all, within an educational framework that acknowledges myriad sources of impact on learning success. While they have come in for criticism, they attempted to ensure education provision through intelligence or learning styles ‘portfolios’ rather than by organising learning via dubiously organised homogeneous ‘ability’ groups. Their theoretical positions may be ‘flaky’ (White Citation2002) but they stimulated debate about providing a rich learning environment for all.

As an expression of values, meeting heterogeneous needs may be found wanting during ITE. Even though values are at the heart of educationalists’ work, a pressing need for practical solutions may obviate values’ reflection. The ‘here-and-now’ of practice may cause the PST to feel she must ‘do’ rather than ‘identify’ or ‘know' teaching (after Adams and McLennan Citation2021). As the enactment of differentiation depends upon unique interrelationships between what teachers know, what they can do and what they believe, eliding these is to either reflect with little influence on practice or to action hints and tips with limited professional impact. PSTs’ beliefs significantly impact how they differentiate (Monsen, Ewing, and Kwoka Citation2014; Tomlinson and Imbeau Citation2010; Varcoe and Boyle Citation2014) and this undoubtedly impacts teaching and children’s learning.

Nonetheless, since the 1980s, differentiation has been cited as PSTs’ most common difficulty (Varcoe and Boyle Citation2014; Veenman Citation1984) for it challenges assumptions about ability, learner readiness, standards, etc. How teachers differentiate differs across schools, classes and pupils depending on varying funds of PST, and teacher institutional knowledge and perceived next learning steps. Done well, differentiation enables curriculum accessibility for all, enhances equitable educational opportunities, increases pupil motivation and participation and engenders learning success.

Despite this, a major hurdle faced by teachers following fewer traditional and more heterogeneous educational philosophies was that limited practical support was given to help children participate in a wider society (Monsen, Ewing, and Kwoka Citation2014; Rouse Citation2008). Additionally, ITE often had a limited focus on differentiation matters while a 2017 content analysis of Scottish ITE programmes indicated that university time spent on equality had increased (Scottish Government Citation2017a). Similar findings (Scottish Government Citation2017b, 4) of readiness to teach highlighted that probationary teachers often do not feel experienced enough to differentiate appropriately. The first review in this latter report emphasised the need to support PSTs to develop praxis in supporting the needs of all learners. While there has been an increase in ITE hours covering equity-related themes generally, these do not readily translate into effective differentiation practices.

However, differentiation approaches can impact negatively children’s learning. Indeed, the importance of a positive learner identity has been highlighted to increase motivation and participation. When children are in homogeneous sub-groups resulting from predetermined ‘ability’ assumptions, Hart, Drummond, and Mcintyre (Citation2013) emphasise that this can exacerbate losses in equity. Boaler, Wiliam, and Brown (Citation2000) posit that fixing expectations about pupil learning often elides formative assessment and slows progression. Possibly, by trying to support all learners through the provision of ‘levels’ for different children, teachers may be widening learning gaps and setting limits on children’s progression. Furthermore, Tomlinson (Citation2017) reports that standardised testing may be an obstacle to promoting differentiation as a value position and subsequently raise barriers that inhibit attainment for various groups of children. Tension exists when trying to provide learning for different children working differently within the same age and stage.

The Scottish context for differentiation

While inclusive methods are enacted differently in many countries, differentiation is often promoted as an effective tool to meet a multiplicity of needs (Wan Citation2017). Specifically, it is said to support a range of diverse learners within mainstream classrooms (Arthur-Kelly et al. Citation2013) with avowed intent to include all children (Tomlinson and Imbeau Citation2010) through ‘varied approaches to the content, the process, and/or the product in anticipation of or in response to student differences in readiness, interests, and learning need’ (Tomlinson Citation2017, 10) and based on the belief that all can succeed. Internationally, differentiation practice has become more common as an educator response to meet the diversity inherent in heterogeneous classrooms (Graham et al. Citation2021; Hamilton and O’Hara Citation2011).

In keeping with international changes steering differentiation away from the provision of something additional or different for ‘some’, in the Scottish inclusive education paradigm, differentiation has moved towards provision for ‘everyone’ (Hart, Drummond, and Mcintyre Citation2013). This shift is ‘believed to have particular relevance to social justice and equity in Scottish Education’ (Florian, Young, and Rouse Citation2010, 710) so broadening understanding of diverse learner needs (Education Act Citation2004/Citation2009/Citation2017; Standards in Scotland’s Schools Etc Act Citation2000) alongside a more focused learner-centred education (Children and Young People’s Act Scotland Citation2014; Getting It Right for Every Child, 2008). Although a significant number of children within mainstream Scottish schools are recorded as having ASNs (30.9%), differentiation is advanced as an approach to planning effectively to meet all learning needs and is identified as a key feature of the Standards for Provisional and Full Registration (General Teaching Council Scotland (GTCS) Citation2021a; Citation2021b).

The NIF (Scottish Government Citation2023a) identifies a children’s rights approach which highlights that inclusion and targeted support are one of four key lenses through which workstreams are to be managed (Scottish Government Citation2023b). While not mentioning differentiation directly, the Muir Report (Muir Citation2022) proposes establishing a new national Scottish education agency with a brief to provide ‘ … bespoke support and professional learning at regional and local levels’ (Muir Citation2022, 5). It seems contradictory to tailor system-wide developments to meet identified demand while classroom practice remains wedded to pedagogic approaches ignoring multiplicity of needs.

This Scottish shift away from differential provision afforded through, for example, ASN towards wider conceptions of educational need and how to provide for this, positions all teachers as needing to respond to diversity and plurality. As a feature of contemporary education systems, particularly following the Coronavirus pandemic, meeting the needs of individual children and young people has come to the fore. In its Coronavirus Special Edition: back to school, the Organisation for Economic and Social Co-Operation (OECD) (Citation2020, 8) highlighted the need to adjust teaching ‘ … to the individual learning losses and gains during school closure … ’ In Scotland, the report Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: into the future (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Citation2021) noted that multi-level secondary classes caused professional challenges in delivering the curriculum to all. This is also relevant for Scottish primary schools in rural/remote areas particularly where vertical grouping is often deployed. Although the recent National Discussion on Scottish Education (Scottish Government Citation2023b) highlighted a significant need for all involved in education, differentiation was not discussed. The term was also unmentioned in the NIF update (Scottish Government Citation2023a). However, in ITE differentiation is expected to be utilised to plan and teach effectively to meet learner needs (GTCS Citation2021a, standard 3.1.1).

Differentiation, ITE and PSTs

For effective differentiation, all children must be valued, and teachers must believe that all can succeed. If learning requires a growth mindset endeavour, then every child should be focused, challenged and engaged. Although research acknowledges that teachers care about their students and enthusiastically support inclusive differentiation approaches, teaching practices often do not align (Brighton Citation2003). Specifically, for ASNs, a persistent medical model prevails; attention to the learning needs centres on ameliorating ‘within person diagnoses’ (Rouse Citation2008). ‘Solutions’ are ‘found’ that encapsulate approaches where ‘deficiency’ foregrounds educational interventions (Adams Citation2008). While differentiation is more than an ‘ASN issue’ we note the ubiquity of this medical model. Although inclusion and social justice should form the heart of education and ITE programmes, globally student teachers feel ill-equipped to teach inclusively (cf. Florian and Black-Hawkins Citation2011; Rouse Citation2008).

While some hold that ITE should focus on classroom skills (e.g. DfE Citation2010) research indicates that PST placement engagement is a product and indicator of developing beliefs (Monsen, Ewing, and Kwoka Citation2014, Black-Hawkins and Florian, Citation2012, Richardson Citation1996) that do not always originate in well-reasoned action or evidence. It is important that ITE provides opportunities for an examination thereof (He and Levin Citation2008) for tacit suppositions about students, curriculum, classrooms, etc. locate emerging teacher assumptions. Unless student teachers examine reasons for action, ITE programmes are unlikely to impact beliefs or practice (Florian, Black-Hawkins, and Rouse Citation2016).

Importantly, PSTs’ beliefs varyingly stem from nascent personal experience and are the product of myriad encounters: their time as a pupil; classroom assistant; observer; or parent/carer perhaps. Personal positioning of education originates in various life events. Praxis (personal, theoretical positions resulting from classroom experience (Roth Citation2002)) is certainly one placement outcome. However, reliance on personal experience is insufficient; praxis is only valuable in relation to enduring theory with a basis in research-informed endeavours (Adams and McLennan Citation2021). Without this, praxis becomes hearsay, ideology or mere whimsy.

The research

An examination of praxis is difficult: theory does not always sit with experience and local, professional interactions may challenge personal views. For ITE to contribute to professional development, it must examine how PSTs ‘come to know’. In Scotland, political vision is explicit in its desire to reduce the attainment gap within a framework of excellence and equity (Scottish Government Citation2017c). Given that differentiation is cited as one mechanism to achieve this, it is propitious to identify PSTs’ differentiation attitudes and beliefs. Accordingly, research was conducted to answer the question, ‘What are the beliefs and attitudes of pre-service teachers towards differentiation?’

Research design

The research was situated in an interpretivist paradigm where ‘reality’ depends on individual positioned constructs (cf. Harré Citation2004) to explore opinions and feelings of attitudes and beliefs of PSTs. We sought to build a situated understanding of phenomena in context (Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003). The qualitative research method of interviews was utilised.

Sampling strategy

The whole cohort of 2018–19 PGDE Primary Education students was invited to take part in this research project. Clearly highlighted in the introduction to the research was that no student was obliged to take part, and that non-participation would not lead to any detriment in PGDE success. Participation was entirely optional and voluntary. The invitation to all was made at the end of a lecture, not delivered by any of the authors and also via a group email. Any PST who showed interest in participating at this stage was provided with a participation information sheet. This shared further information about the study including their potential involvement, anonymity, confidentiality and that participants had the option to withdraw from the study at any time up until the merging of anonymised data for analytical purposes. It was clearly stated that participation or otherwise in this research would have no bearing on the outcome of their PGDE programme.

Before coming to the interview, participants were given a consent form reiterating these key points. Only PSTs, who consented were interviewed and included in this research project.

Sample

Thirteen out of fifteen PSTs were females and two were males. This is representative of the PGDE gender demographic on the PGDE widely. The age range was twenty-two to fifty-four. Six participants progressed into the PGDE directly following undergraduate (UG) studies. Seven out of nine participants had worked in schools and/or early years’ establishments between UG and PGDE studies. Participants thus had varying levels of differentiation knowledge and experience.

Both informant and time triangulation were incorporated to offer validity, improved accuracy and present a fuller picture (Denscombe Citation2014; King, Horrocks, and Brooks Citation2018). All interviews, except one, were conducted on different days in March. By March, participants had completed three out of four placements. One interview was conducted in May after all placements were complete. Each participant was interviewed once, and each interview consisted of new participants.

Data collection tools

Data were generated through qualitative, unstructured, mini-focus group interviews. These interviews were most suitable to collect PSTs’ opinions, feelings, emotions and experiences (Denscombe Citation2014). Interviews allowed participants to offer more thoughtful and complex contributions and to explore in greater detail individual experiences and perspectives in an inductive manner (Bryman Citation2016). Participants controlled their language and their terms which facilitated greater insight into how they thought about the world (King, Horrocks, and Brooks Citation2018).

The fifteen PGDE Primary PSTs were interviewed in 2019 in three groups of four and one group of three. Each mini-focus group interview elicited PSTs’ concepts and theories with one author as moderator.

Each focus group opened with a moderator posed question: ‘What are your beliefs and attitudes towards differentiation?’ The intention was for participants to steer the conversation. Each focus group was audio-recorded and the moderator took contemporaneous notes. Data collection took place face-to-face, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data analysis process

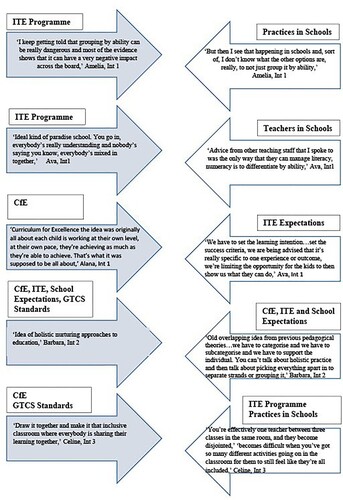

Elements of grounded theory and thematic analysis were deployed for data analysis. Data were sorted into concepts and categories formed from the ongoing development of relationships across the data (Gibbs Citation2018). Middle-range theories evolved (Charmaz and Belgrave Citation2012). From the open and axial coding, selective coding was generated, and salient points were identified ro inform theory generation (see ).

Table 1. PSTs’ beliefs and attitudes towards differentiation.

Ethical considerations

Clearly, when researching with one’s students, power imbalance must be considered. To overcome any sampling bias, the whole student cohort was approached to remove feelings of obligation and to ‘distance’ the focus-group moderator from individual students. The moderator was known to the students; they had taught them previously by large-scale lectures. However, in such teaching situations, it is very difficult for staff-student relationships to develop. Accordingly, the moderator carefully presented the research, parameters for participation and procedures for anonymity/ethics during a large-scale lecture. It was clearly stated that data would remain anonymous and confidential, and that participation would have no bearing on PGDE success and was completely voluntary. Students were asked to contact the moderator so that feelings of coercion could be avoided. Furthermore, as all PGDE assignments are submitted anonymously no staff involved in the research could connect any assignment to any student; this was also reiterated to students. Neither author was involved in supporting any of the students interviewed during their school placement.

Although participants knew the moderator, it was felt this positively contributed to the development of a collaborative, research/working relationship. Students did not seem to participate unwillingly or be stymied in their responses. The moderator was situated: they were, until shortly before the research, a primary school teacher, then they worked in ITE. Hence, ‘bracketing’ was adopted; the researcher set aside their assumptions and deployed ‘inter-subjectivity’ to align commonly reported threads (Creswell and Poth Citation2007). Ethical permission was granted from the Institute of Education at the university in question. The second author acted as the research supervisor.

Results

Overall, PSTs noted that differentiation was necessary to effectively meet diverse learning needs. However, they also felt an overwhelming sense of stress and pressure to differentiate to meet the needs of all learners, partly due to conflicting messages from key influencers. To expand, PSTs believed that differentiation, when used critically to ensure no learner detriment, could progress learning for all. ‘Can-do’ PST attitudes showcased a willingness to try myriad differentiation to gain experience and expertise. Participants highlighted that ongoing assessment, experiences, knowledge and resources, time and experience with learners were key to ensuring that differentiation through content, process, product and environment is pitched appropriately.

This said, there were much greater feelings of unease. For most, differentiation was a ‘hurdle’ to ‘overcome’ during ITE and subsequently. Many felt pressure to succeed not only so they might graduate but also so they might meet the needs of all in their care. They often felt they lacked experience, resources, confidence and knowledge. They believed that at times differentiation by fixed ability grouping was detrimental to pupil identity and learning. As Celine states in interview 3:

Like, sometimes kids, I think they kind of fall into their group label. If it’s ability grouping, they become the lower group.

Discussion

PSTs expressed positive and negative beliefs, can-do and can’t-do attitudes. Within the discussion, we here move away from reporting the findings to concentrate on problematic issues as these were expressed with more significance and purpose. Moreover, as pre-service teacher educators, a key purpose of this research was to consider how to improve ITE experiences to build teacher self-efficacy within this major challenging educational theme of differentiation; thus, the difficulties experienced must be scrutinised. In summary, the themes generated are

The role for ‘ability’

Pressure and stress

Conflicting messages

We reiterate here that inclusion and equity are key educational values encompassed within the social justice standard for Full and Provisional Registration for all teachers in Scotland (GTCS Citation2021a, standard 1.1). Furthermore, Donaldson (GTCS Citation2021b) reiterated that ‘quality teaching is central to the wellbeing and success of Scotland’s Young people’, the implication being that all teachers should be supported to develop professionally throughout their careers. Policy-wise, then, significant areas of focus for teacher education and development are developing the ability to be able to address inequalities, ASNs and distressed childhood behaviours (2010, 36).

Furthermore, such International foci position differentiation as vital for practice over time as a professional response to meeting diversity in heterogeneous classrooms (Graham et al. Citation2021; Hamilton and O’Hara Citation2011). As evidenced previously (see ), PSTs grapple with educational values and expectations from a range of key influencers and their own beliefs and attitudes in pursuit of differentiating inclusively.

The role for ability

Ability, within differentiation, is perceived as Janus-faced: both advantageous and disadvantageous. Participants viewed differentiation by ‘ability’ to be crucial to ensuring each child is taught at their point of need. As expressed by Ava in interview 1 when discussing differentiation by level of English language

If they’re actually achieving well in that setting with a range of peers, is that not a healthier approach than limited support and a really acute awareness that you’re not quite at the level of your peers?

If you were doing it in by ability, their self-esteem and stuff would suffer. (Bambi, interview 2)

Pressure and stress

The Scottish Universities’ Inclusion Group recently shared that what makes differentiation inclusive may not be explicitly expressed within ITE or schools (Cantali, Florian, and Graham Citation2022). This makes it more difficult for PSTs to enact their educational values of inclusion and equity through differentiation in an evidence-based, informed and confident manner; conflicting messages perceived by PSTs about differentiation hence led to stress and uncertainty. Expressed alternatively, this is suggestive of the oft-noted dichotomy between (as noted in ) child-centred (on the left) and teacher-centred (on the right). Another key area of conflict is for whose benefit do teachers differentiate: a child-centred approach in a bid to produce successful learners via CfE (The Scottish Government, n.d.) or a methodology employed to ‘manage’ a diverse classroom? Such perspectives were not evident in the data but are elevated when teacher practice comes to the fore.

Conflicting messages

Underpinning the key themes of feeling pressure and stress while managing conflicting messages stems from a lack of experience, knowledge, agency and confidence (see ). As demonstrated in interview 1 where Amelia spoke about how differentiation is ‘ … really difficult’, Abigail shared that she didn’t ‘ … really feel confident in doing it or that we’ve really touched on it’ and Ava spoke of guilt,

… as a trainee teacher … that’s, maybe, one- the impact of that one lesson that you have on a child’s sense of their own ability, but, actually, what’s happened is you’ve got it wrong.

And to me, differentiation is very- I value it a lot. I think it’s crucial. And that is the area that I worry about it, because it’s – when you look at it, it’s almost like that mountain that you have to climb to so, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to be there ever’. But you have to just put your head down and go one step at a time’. ‘But if I think about differentiation, it’s what made me think, “This is an impossible job”.

The pressure it puts on us, because the huge difference a teacher can make to a student. (Bobby)

Because, obviously, we’re under so much pressure as it is, as student teachers to meet certain standards and guidelines. Are we putting too much pressure on ourselves? When do we stop? When do we say enough, that’s enough differentiation? (Bambi)

Teachers’ beliefs in being able to perform well or having the locus of control/agency to action change also translate to positive achievements for learners (Morris, Usher, and Chen Citation2017). Teachers with a keen sense of self-efficacy also demonstrate increased resilience, are more willing to be creative (Jerald Citation2007) than peers who doubt themselves and are less susceptible to burnout (McCartney et al. Citation2018). If PSTs experience self-doubt and lack self-efficacy, over and above what might be deemed acceptable in an emerging teacher, then it is challenging for them to oppose segregating practices seen on placement even when their educational values oppose this. This could result in PSTs copying classroom practices they observe (Chesnut and Burley Citation2015) to be seen to meet the Standards for Provisional Registration (SPR, GTCS Citation2021a) by key influencers () with a stake in their success. Perhaps the lack of permission to enact the educational values upon which they have spent time critically reflecting could lead to stress, pressure and lack of job satisfaction. Considering this, the sense of pressure and stress to ‘Get it Right for Every Child’ while faced with two dominant and opposing inclusion perspectives seems to result in conflicting beliefs, attitudes and praxis of differentiation. This, as Barry shared, makes teaching ‘an impossible job!’

Recommendations for ITE

Aligning with Graham et al.’s (Citation2021) definition and considering the interdependency and complex tensions between differentiation and inclusion, many of the recommendations below support inclusive practice.

First, we posit that ITE must facilitate PSTs to develop knowledge, theory and practical experience to enact inclusion and differentiation alongside critical reflection to tackle feelings of professional inadequacy (Beacham and Rouse Citation2012; Florian and Linklater Citation2010; Florian, Young, and Rouse Citation2010; Maciver et al. Citation2021; Sosu, Mtika, and Colucci-Gray Citation2010). Drawing from a range of school placement experiences (Florian and Linklater Citation2010) is a positive feature of an ITE system built on a partnership approach between schools, local authorities and HEIs. Each partner supports PSTs to feel better prepared to tackle conflicting messages, thus lessening self-doubt and stress. This can also bridge ITE HEI-school relationships so facilitating positive beliefs and ‘can-do’ attitudes. This is not without tension though as the role outcomes for the different educational sectors involved in ITE often present tensions and contradictions that are not easy to manage.

Second, PSTs could be encouraged to explore supportive frameworks and resources to enable them to decipher appropriate differentiation practices. As the National Framework for Inclusion (NFI) in Scotland (SUIG Citation2022) aligns with Tomlinson’s framework for differentiation (2017) and Florian and Spratt’s Enacting Inclusion Model (Citation2013). An exploration of these could provide critical reflection, so helping to build bridges between HEI and schools while continually supporting the development of positive beliefs.

Third, an additional framework and bank of certified resources to support teachers’ understanding of specific needs could be deployed to tackle feelings of insufficient knowledge and how this can be overcome through a concentration not only on knowledge but also on feelings of developing agency. This could provide significant inter-professional experiences through collaboration with specialists (such as educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, etc.) to explore how the need might be supported. Incorporating this into ITE programmes could assist PSTs to develop knowledge and confidence.

Finally, time should be allotted for PSTs to engage in educational research. Beginner teachers report that often education research is not for them or is inaccessible (McCartney et al. Citation2018). Increasing accessibility would help beginner teachers value research, increase engagement thereon, support critical reflection and inform the next steps in teaching. Possibly, there is not enough time within a 36-week PGDE programme to enable PSTs to engage sufficiently with such recommendations; feasibly, Scotland should look to extend PGDE time to support PSTs’ professional development when tackling major challenges such as differentiation.

Limitations

The research was conducted with a small sample of PSTs from one Scottish university; more participants would, therefore, widen reach. As the research was unfunded, travel, time, convenience and relationship factors will have played a role in accessing participants (Denscombe Citation2014). As with researching in any community where one is known, participants may have shared views they believed their tutor wanted to hear. However, the positive relationship between the tutor and participants was thought advantageous and seemed to put participants more at ease. For future studies, how data generation is conducted and with whom should continue to be considered.

Conclusion

While it is natural most PSTs upon graduation feel confident about certain matters (see www.mquite.scot), differentiation persists as an area for development. It is unclear whether feelings stem from messages during the HEI part of their programme, time on placement or because differentiation is ‘difficult’. Partly, differentiation is a value and philosophical matter and pertains to how PSTs understand: their role; their agency; pupil needs and pedagogic ends. It is, however, also a practical endeavour, one which requires a critique of the provision PSTs feel they should and can offer and feel they are offering.

Differentiation is more than a task: it is a litmus test for myriad teaching positions. It may originate in views that celebrate myriad pupil perspectives and thus encourage an approach based on diagnosing needs and applying mediating techniques. Here, ASN and ability ideas come to the fore and drive classroom and school organisations to provide for ‘most pupils’ while accepting that such norms might not accommodate all. Ensuing ameliorative organisation manufactures homogeneity; indeed, the data above indicate this as a major concern. PSTs speak of ‘ability’ as defining classroom organisation, particularly in maths and how this leads to pressure to ‘meet need’ but also to be seen to act responsibly to ‘fit in’. Such conflicting messages are redolent of HEI/school boundaries and how, while there may be a common desire to meet pupil needs, this is often perceived and actioned very differently.

Conversely, differentiation may generate professional interpretations that seek to deploy mechanisms to specifically work with heterogeneity: approaches for all and inclusive of all. However, such Human Rights approaches seem often not to be elevated in PST experiences. Evident tensions between practitioners’ values and praxis result in conflicting messages and appear to cause significant levels of pressure and stress for PSTs.

Finally, the research for this paper occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic and this further militates against differentiation development unless attention is paid to understanding pupil needs as a human-rights issue, rather than something stemming from within-pupil attributes.

Ethical approval

This research was granted ethical approval by the University of Strathclyde’s School of Education.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all participants, and the anonymous reviewers for their supportive words and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Raw and anonymised data can be requested, in writing, from the corresponding author.

References

- Adams, P. 2008. “Considering ‘Best Practice’: The Social Construction of Teacher-Activity and Pupil-Learning as Performance.” Cambridge Journal of Education 38 (3): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640802299635.

- Adams, P., and C. McLennan. 2021. “Towards Initial Teacher Education Quality: Epistemological Considerations.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 53 (6): 644–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1807324.

- Arthur-Kelly, M., D. Sutherland, G. Lyons, Mac Farlane, and P. Foreman. 2013. “Reflections on Enhancing Pre-service Teacher Education Programmes to Support Inclusion: Perspectives from New Zealand and Australia.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (2): 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.778113.

- Beacham, N., and M. Rouse. 2012. “Student Teachers’ Attitudes and Beliefs About Inclusion and Inclusive Practice.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 12 (1): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01194.x.

- Black-Hawkins, K., and L. Florian. 2012. “Classroom Teachers’ Craft Knowledge of Their Inclusive Practice.” Teachers and Teaching 18 (5): 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732.

- Boaler, J., D. Wiliam, and M. Brown. 2000. “Students’ Experiences of Ability Grouping-Disaffection, Polarisation and the Construction of Failure 1.” British Educational Research Journal 26 (5): 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/713651583.

- Brighton, C. M. 2003. “The Effects of Middle School Teachers’ Beliefs on Classroom Practices.” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 27 (2–3): 177–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320302700205.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cantali, D., L. Florian, and A. Graham. 2022. Mapping Inclusive Practice and Pedagogy in Scotland’s ITE Courses. https://www.sera.ac.uk/blog/2022/02/01/inclusive-education-network-seminar-mapping-inclusive-practice-and-pedagogy-in-scotlands-ite-courses/.

- Charmaz, K., and L. Belgrave. 2012. “Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft 2: 347–366. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218403.n25.

- Chesnut, S. R., and H. Burley. 2015. “Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Commitment to the Teaching Profession: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review 15: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.001.

- Children and Young People’s Act Scotland. 2014.

- Chopra, R. 2008. “Factors Influencing Elementary School Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education.” In British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, 3–6. Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University.

- Cremin, T., and J. Arthur. 2014. “1 Providing for Inclusion.” In Learning to Teach in the Primary School, 373–386. London: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Method: Choosing among Five Approaches. London: Sage.

- Denscombe, M. 2014. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. London: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Department for Education (DfE). 2010. The Importance of Teaching: The Schools White Paper 2010. Norwich: The Stationery Office.

- Donaldson, G. 2011. Teaching Scotland’s Future: Report of a Review of Teacher Education in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/2178/7/0110852.

- Education Scotland. 2015. How Good Is Our School 4. https://education.gov.scot/nih/Documents/Frameworks_SelfEvaluation/FRWK2_NIHeditHGIOS/FRWK2_HGIOS4.pdf.

- Education Scotland. 2015. Differentiated Learning in Numeracy and Mathematics: Briefing 1. Livingston: Education Scotland. Differentiated learning in numeracy and mathematics (2015): Briefing 1 | Resources | National Improvement Hub. https://education.gov.scot/resources/differentiated-learning-in-numeracy-and-mathematics/.

- Education Scotland Act 2004, 2009, 2017

- Florian, L., and K. Black-Hawkins. 2011. “Exploring Inclusive Pedagogy.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (5): 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.501096.

- Florian, L., K. Black-Hawkins, and M. Rouse. 2016. Achievement and Inclusion in Schools. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315750279.

- Florian, L., and H. Linklater. 2010. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive Education: Using Inclusive Pedagogy to Enhance Teaching and Learning for all.” Cambridge Journal of Education 40 (4): 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588.

- Florian, L., and J. Spratt. 2013. “Enacting Inclusion: A Framework for Interrogating Inclusive Practice.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (2): 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.778111.

- Florian, L., K. Young, and M. Rouse. 2010. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive and Diverse Educational Environments: Studying Curricular Reform in an Initial Teacher Education Course.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (7): 709–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603111003778536.

- Gardner, H. 1983. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

- General Teaching Council for Scotland. 2021a. Professional Standards 2021 Scotland’s Teachers. Comparison of Professional Standards 2012 and 2021. https://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-standards/professional-standards-2021-engagement.aspx.

- General Teaching Council for Scotland. 2021b, January 14. GTC Scotland Lecture 2021 with Professor Graham Donaldson. https://www.gtcs.org.uk/News/events/january-lecture-2021.aspx.

- Gibbs, G. R. 2018. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Vol. 6. Sage Publications Limited.

- Graham, L. J., K. De Bruin, C. Lassig, and I. Spandagou. 2021. “A Scoping Review of 20 Years of Research on Differentiation: Investigating Conceptualisation, Characteristics, and Methods Used.” Review of Education 9 (1): 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3238.

- Hamilton, L., and P. O’Hara. 2011. “The Tyranny of Setting (Ability Grouping): Challenges to Inclusion in Scottish Primary Schools.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (4): 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.009.

- Harré, R. 2004. Positioning Theory. http://www.massey.ac.nz/_alock/virtual/positioning.doc.

- Hart, S., M. J. Drummond, and D. Mcintyre. 2013. “Learning Without Limits: Constructing a Pedagogy Free from Determinist Beliefs About Ability.” The SAGE Handbook of Special Education: Two Volume Set 1: 439. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282236.N28.

- He, Y., and B. B. Levin. 2008. “Match or Mismatch? How Congruent Are the Beliefs of Teacher Candidates, Cooperating Teachers, and University-Based Teacher Educators?” Teacher Education Quarterly 35 (4): 37–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23479173.

- Jerald, C. D. 2007. “Believing and Achieving. Issue Brief.” Center for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement 1–8. ED495708.pdf.

- King, N., C. Horrocks, and J. Brooks. 2018. Interviews in Qualitative Research. London: SAGE Publications Limited.

- Maciver, D., C. Hunter, L. Johnston, and K. Forsyth. 2021. “Using Stakeholder Involvement, Expert Knowledge and Naturalistic Implementation to Co-Design a Complex Intervention to Support Children’s Inclusion and Participation in Schools: The CIRCLE Framework.” Children 8 (3): 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8030217.

- McCartney, E., H. Marwick, G. Hendry, and E. C. Ferguson. 2018. “Eliciting Student Teacher's Views on Educational Research to Support Practice in the Modern Diverse Classroom: A Workshop Approach.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 342–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1498748.

- Monsen, J. J., D. L. Ewing, and M. Kwoka. 2014. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusion, Perceived Adequacy of Support and Classroom Learning Environment.” Learning Environments Research 17 (1): 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-013-9144-8.

- Morris, D. B., E. L. Usher, and J. A. Chen. 2017. “Reconceptualizing the Sources of Teaching Self-Efficacy: A Critical Review of Emerging Literature.” Educational Psychology Review 29 (4): 795–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9378-y.

- Muir, K. 2022. Putting Learners at the Centre: Towards a Future Vision for Scottish Education. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic and Social Co-Operation). 2020. Coronavirus Special Edition: Back to School. Paris: OECD.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development). 2021. Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: Into the Future, Implementing Education Policies. Paris: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/bf624417-en.

- Pollard, A., K. Black-Hawkins, G. Cliff-Hodges, P. Dudley, and M. James. 2014. Reflective Teaching in Schools: Evidence-Informed Professional Practice. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Richardson, V. 1996. “The Role of Attitudes and Beliefs in Learning to Teach.” Handbook of Research on Teacher Education 2 (102-119): 273–290.

- Ritchie, J., and J. Lewis. 2003. Qualitative Research Practice. London: Sage.

- Roth, W. M. 2002. Being and Becoming in the Classroom. London: Ablex Publishing.

- Rouse, M. 2008. “Developing Inclusive Practice: A Role for Teachers and Teacher Education.” Education in the North 16 (1): 6–13. DRAFT. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/education/documents/journals_documents/issue16/EITN-1-Rouse.pdf.

- The Scottish Government. 2017a. Initial Teacher Education Content Analysis. https://www.gov.scot/publications/initial-teacher-education-content-analysis-2017/.

- The Scottish Government. 2017b. Gathering Views on Probationer Teachers’ Readiness to Teach. https://beta.gov.scot/publications/gathering-views-probationer-teachers-readiness-teach/.

- The Scottish Government. 2017c. Pupil Equity Funding. https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-equity-fund-national-operational-guidance-2017/.

- Scottish Government. 2023a. 2023 National Improvement Framework (NIF) and Improvement Plan Summary Document. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2023b. All Learners in Scotland Matter: The National Discussion on Education Final Report. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Scottish Universities Inclusion Group. 2022. The National Framework for Inclusion in Scotland. 3rd ed. National Framework for Inclusion - The General Teaching Council for Scotland. https://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-standards/national-framework-for-inclusion/.

- Sosu, E. M., P. Mtika, and L. Colucci-Gray. 2010. “Does Initial Teacher Education Make a Difference? The Impact of Teacher Preparation on Student Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Educational Inclusion.” Journal of Education for Teaching 36 (4): 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2010.513847.

- Standards in Scotland’s Schools Etc Act. 2000.

- Tomlinson, C. A. 2017. How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., and M. B. Imbeau. 2010. Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom. Virginia, VA: ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., and M. B. Imbeau. 2012. “Common Sticking Points About Differentiation.” School Administrator 69 (5): 18–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301553796_Common_sticking_points_about_differentiation.

- United Nations. 1989. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the child. https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/.

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- Varcoe, L., and C. Boyle. 2014. “Pre-service Primary Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education.” Educational Psychology 34 (3): 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785061.

- Veenman, S. 1984. “Perceived Problems of Beginning Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 54 (2): 143–178. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543054002143.

- Wan, S. W. Y. 2017. “Differentiated Instruction: Are Hong Kong in-Service Teachers Ready?” Teachers and Teaching 23 (3): 284–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1204289.

- White, J. 2002. The Child’s Mind. London: Routledge.