ABSTRACT

This article takes stock of the current trends in research, policy and practice regarding the role of language in the dialogic classroom. The article uses the policies of two different educational jurisdictions as counterpoints to highlight the different ways that oral language can be positioned within primary curricula. It reflects on current and recent research literature, exploring how language can promote the collaborative learning that is central to dialogic pedagogy, highlighting the value of less formal registers or less ‘certainty’ in the proposal of ideas. The article then offers a linguistic-ethnographic analysis of what this looks like in practice, drawing on classroom observational data gathered in English primary schools. Finally, these three strands of theory, policy and practice are brought together, scoping ways forward for the inclusion of language and dialogue in primary education.

Introduction

Classes where there is an emphasis on the generation of ideas through whole class and group talk, and where children’s voices and perspectives are heard, valued and engaged with by the teacher have been described as dialogic (Alexander Citation2008, Citation2020). The definitions of this type of pedagogy and close analysis of the interactions between teachers and children within it have gained ground in the late 90s and early part of the twenty-first century (see for example, Alexander Citation2008; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Nystrand Citation1997). However, recognition of the importance of learning as an active and interactive endeavour stretches back through the twentieth century at least, with educational thinkers such as Dewey (Citation1933) and Donaldson (Citation1978) placing inquiry and discovery at the heart of learning. The role of oral language is perhaps more implicit than explicit in these older theories, but at the heart of a pedagogy that values the sharing of ideas and collaborative sense-making, lies the means by which we communicate and respond to each other.

This article takes stock of the current trends in research, policy and practice regarding the role of language in the dialogic classroom. It draws on data generated as part of a large European project aimed at developing children’s cultural competence through concentrating on the dialogic dispositions of tolerance, empathy and inclusion (DIALLS Citation2021). The article uses the policies of two different educational jurisdictions in the project (England and Wales) as counterpoints to highlight the different ways that oral language can be positioned within primary curricula. It reflects on current and recent research literature, exploring how language can promote the collaborative learning central to dialogic pedagogy, highlighting the value of less formal registers or less ‘certainty’ in the proposal of ideas. The article then offers a linguistic-ethnographic analysis of what this looks like in practice, drawing on project data gathered in England. Finally, these three strands of theory, policy and practice are brought together, scoping ways forward for the inclusion of language and dialogue in the curriculum in ways that can support young learners to be global citizens. The article argues that language in the dialogic classroom is a powerful, collaborative learning tool that serves a social and cultural purpose towards building intercultural competence and understanding of others with empathy and inclusion.

How can oral language be positioned in primary curricula

Schools in England and Wales were included in a project aiming to support the inclusion of dialogue in classroom learning (DIALLS Citation2021). Schools in England were part of the main data collection phase of the DIALLS project. Then in a later project phase, online materials were trialled working with local authorities and schools in Wales, to plan how they might sit alongside the existing curriculum. The curricular policies of these two educational jurisdictions are useful to compare, not least because whilst geographical neighbours, they reflect very different approaches to the positioning of oral language within their frameworks for learning and teaching.

In England’s National Curriculum (DfE Citation2013) ‘Spoken Language’ is included in the programme of study for English. In a document of 88 pages, the programme of study for spoken language occupies just over a page, with little emphasis on progression other than that children should build on skills they have been taught previously. In the initial ‘aims’ section of the curriculum document it states that,

the quality and variety of language that pupils hear and speak are vital for developing their vocabulary and grammar and their understanding for reading and writing. Teachers should therefore ensure the continual development of pupils’ confidence and competence in spoken language and listening skills. (DfE Citation2013, 3)

In the new Curriculum for Wales (Welsh Government Citation2021), a different approach is taken with a ‘Languages, Literacy and Communication’ area of learning and experience. Centring on the importance of spoken language in the formation of own’s identity and understanding of culture, the Curriculum for Wales highlights how, ‘learners should be given opportunities to use languages in order to be effective as they interact, explore ideas, express viewpoints, knowledge and understanding and build relationships’ (Welsh Government Citation2021). The curriculum area highlights key principles around language, stating that, ‘Languages connect us’ (LCU), ‘Understanding Language is key to understanding the world around us’ (UL) and ‘Expressing ourselves through Languages is key to communication’. This framing positions the role of language beyond the articulation of ideas for attainment gains, towards life-long learning competences aimed at belonging and relating to others. Importantly, these principles are the starting point for progression steps (PS) and these make reference to, a ‘sense of belonging’ (PS1, LCU), ‘a relationship between languages, culture and my own sense of Welsh identity’ (PS2, LCU) and to ‘listen empathetically to different people’s viewpoints on various subjects’ (PS3, UL). The approach of the new Curriculum for Wales, starting with clear principles for how language, culture and identity are bound together, speak to the OECD goal of developing globally competent citizens who can, ‘examine local, global and intercultural issues, understand and appreciate different perspectives and world views, interact successfully and respectfully with others’ (OECD Citation2018, 7). This approach is also reminiscent of proposed aims for the primary curriculum that were the result of the extensive Cambridge Primary Review (CPR) of the English Primary Curriculum (2006–2010). In the review report, a clear vision for the place of oral language in the curriculum was proposed, with ‘enacting dialogue’ one of the 12 aims for primary education (Cambridge Primary Review Citation2009, 19). The review argues that, ‘Dialogue is central to pedagogy, between self and others, between personal and collective knowledge, between present and past, between different ways of thinking’ (Cambridge Primary Review Citation2009). The positioning of dialogue at the centre of this learning is discussed in the next section.

Dialogic pedagogy

The impact of dialogic pedagogy has been the subject of much educational research the last 20 years (see for example, Alexander Citation2020; Hardman Citation2019; Howe et al. Citation2019). Typically focusing on a language-rich pedagogy, the role of talk is central to this approach to learning and teaching. In addition to his work leading the Cambridge Primary Review, Alexander is the educationalist most closely associated with the notion of dialogic teaching in the UK. His work significantly extended earlier research into the most effective classroom interactions that highlighted the importance of open questioning and the take-up of children’s ideas by teachers (Nystrand Citation1997). By identifying principles that underpin dialogic teaching, Alexander considered not just the types of interaction that might happen in classrooms but the values and ethos that underpin such a learning environment where knowledge is jointly constructed with children and their ideas prioritised. Refining his ideas in a recent ‘companion’ text (Alexander Citation2020), he argues that these classrooms should be collective, with children and teachers all embarking on a learning journey together; supportive, a place where all children feel able to share their ideas and welcomed to do so; reciprocal, meaning that children and teachers ask and answer queries and take responsibility for sharing different perspectives; deliberative, seeking resolution of differing viewpoints as reasoned positions and outcomes are striven for cumulative in that the learning builds in a coherent manner, and references prior learning; and purposeful, as even though it is open-ended, there are structures and goals in mind (Citation2020, 131). In a recent evaluation of an intervention supporting teachers to become more dialogic in their teaching, the research found consistent, positive effects in English, Science and Maths for all children in Year 5 (nine to ten year-olds), equivalent to about two months additional progress (Education Endowment Foundation Citation2017).

Alexander is not the only researcher to explore the dynamics of dialogic teaching and its impact on attainment. Reviewing research from the later twentieth century onwards, Howe and colleagues synthesised a plethora of studies that highlighted the features of pedagogy that produced what they called ‘educationally productive dialogue’ (Howe et al. Citation2019, 18). Drawing on studies particularly from Northern America, Europe and Israel conducted in the last 25 years the researchers found that there were five themes recurrent in how these studies defined dialogic teaching: the use of open ended questioning; the opportunity for learners to give extended responses and to build on or elaborate the ideas already shared; the acknowledgement and careful critique of different perspectives; the integration of lines of inquiry as differences are sought to be resolved; and finally that participants should be able reflect on the practice of their talk, to consider how successfully their discussions include each other and fulfil goals. Howe and colleagues’ review of the literature around dialogic teaching was part of a study examining whether there was evidence to support the claims that dialogic teaching leads to educational attainment. They set out to explore, ‘degrees of approximation to theoretically productive dialogue’ (Citation2019, 17) evaluating classes against dialogic criteria; and then testing for positive associations with educational attainment. Whilst not without complications and caveats, they concluded that elaboration of previous contributions, a key feature of a dialogic interactions, were positively associated with higher levels of attainment measured in tests at the end of primary education.

These studies have examined the impact of dialogic teaching on educational attainment, yet the underpinning values espoused by Alexander in his discussions of dialogic pedagogy (Citation2008, Citation2020) point to a wider potential of such an approach, and one that has been picked up in other more recent theories and research.

Dialogic pedagogy to promote global competence

Dialogic pedagogy is a much broader concept than simply focusing on oracy skills to further reasoning and argumentation. To be ‘in dialogue’ with another means holding in tension different viewpoints and perspectives (Wegerif Citation2013). Classrooms where authentic dialogue is valued involve teachers and children working actively to include each other, to welcome the uncertainty of not having definite ‘answers’ and to empathise with other positions whilst building their own identities and values (Cook, Maine, and Čermáková Citation2022). More than this, a truly dialogic encounter involves making meanings in the moment, with response and further voices always potential. This means that meanings made are necessarily provisional as with additional voices adding to an idea, views can change and adapt. It is educationally valuable to provide children with opportunities to experience discussions that are geared towards multiple perspectives and perhaps less directed towards seeking agreement. In these discussions, the value of different voices and, what the Council of Europe (Citation2018) calls, the tolerance of ambiguity comes to the fore. These qualities move beyond articulating ideas or positioning arguments to seek agreements. They require an openness towards situations of complexity and an ability to suspend judgement (Cook, Maine, and Čermáková Citation2022). For example, discussions around culture, citizenship and democracy are not easily, nor even necessarily desirably, resolvable. They often include context-specific solutions, and most often, multiple viewpoints.

This notion of multiplicity in dialogue poses a slight tension with one of Alexander’s principles (an interesting addition to his original list of five principles published in 2008). He describes deliberation as a principle where participants seek to, ‘resolve different points of view; they present and evaluate arguments and they work towards reasoned positions and outcomes’ (Alexander Citation2020, 131). This added principle sits comfortably alongside with the body of research demonstrating the educational value of alternative perspectives and reasoning (Howe et al. Citation2019; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Nystrand Citation1997; Soter et al. Citation2008). However, it seems in contrast with the notion of genuine dialogue (Buber Citation1947), which seeks to embrace multiple perspectives accepting that neat solutions may not be desirable. As Wegerif describes:

In a real dialogue we learn only if there are different views. These different views are not always just different perspectives on a single world such that we can agree together once we see the bigger picture. Often the different worlds of experience found in dialogue together are not reducible to one single ‘correct’ view but really are different – ontologically different. (Wegerif Citation2018)

The concept of dialogue as a social practice draws on the work of Street (Citation1984). He defined traditional views of literacy as ‘autonomous’ as they imply a context-free set of generic technical skills. His study of communities in Iran led him to make the argument that in an alternative, ideological model, literacy can be seen as a culturally bound social practice, with communication of ideas and values and joint meaning-making at the centre of its purpose. He argued that, ‘literacy practices, then, refer to the broader cultural conception of particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing in cultural contexts’ (Citation2003, 79). Thus there is no one state of ‘attainment’ of literacy as by its definition it is the social act of making and sharing meaning.

The language of dialogue and the importance of provisionality

In discussions where outcomes are not clear, where solutions are neither simple nor sometimes desirable, the language used to express ideas needs to accommodate uncertainty. Studies exploring the language used in reasoning highlight the importance of modal vocabulary such as ‘maybe’, ‘perhaps’ and ‘might’, noting the importance of this speculative language in opening reasoning contributions (Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999) or simply including it in a list of discourse markers that serve as proxies for reasoning (Soter et al. Citation2008). Other studies have paid more attention to the role of provisionality in reasoning (Boyd and Kong Citation2017; Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019), noting how such language can serve as, ‘hooks on which to build inter-subjectivity’ (Cook, Maine, and Čermáková Citation2022, 4) or a, ‘lack of full commitment to a proposal under consideration’ (Rowland Citation2007, 87). The use of provisional language demonstrates that in the articulation of ideas, a speaker is aware of their audience and the hedging of a fully committed proposal shows epistemic modality, or a provisionality in the expression of knowledge (Maine and Čermáková Citation2023). However, the use of this language also has further social value as it is this consideration of audience that implies a relatedness, or ‘I-thou’ stance (Buber Citation1947).

With this underpinning literature framing the study, specific research questions come to the fore in examining the role of language in the dialogic classroom: Firstly, in discussions around social and cultural issues, where there are no clear answers and where multiple voices are encouraged, how are dialogic language moves and instances of provisional language-use correlated? Secondly, how does the language used by teachers and children in these discussions indicate the principles that Alexander (Citation2008, Citation2020) has proposed in his definition of dialogic pedagogy?

Methodology

Investigating research questions that link macro and micro analyses of classroom talk (Copland and Creese Citation2015) requires a methodology that can capture both the intricacies of the language used, but also the socio-cultural contexts in which it is happening. Linguistic ethnography (Rampton Citation2007) offers such an approach by combining, ‘linguistic methods for describing patterns of communication with ethnographic commitments to particularity, participation and holistic accounts of social practices’ (Lefstein and Snell Citation2014, 185). Taking such an approach has been criticised as potentially falling between two stalls and not engaging either macro or micro analysis successfully (Hammersley Citation2007), but the work of Lefstein and Snell and colleagues (Lefstein and Snell Citation2014; Lefstein, Snell, and Israeli Citation2015) has demonstrated how useful it can be to qualitatively unpack classroom dialogue where the interactional principles, politics and power structures are complex and hidden to simple observational techniques.

The DIALLS project gathered observational data from classrooms in 7 project countries, and transcriptions of these lessons exist as a multilingual database (Rapanta et al. Citation2021). However, in order to apply a linguistic ethnographic approach, rather than a broader corpus linguistic analysis, the data reported in this article was gathered in England and observed as part of ongoing professional learning dialogues with the project’s classes and teachers. Data was collected from a series of lessons where primary-aged children watched or read a wordless text (films and picturebooks) together as a class and used them as a stimulus for discussions about cultural themes in a ten-week programme. Twenty classroom lessons in the rural East of England were observed (ten lessons from Year 1 classes – five and six year-olds, and ten lessons from Year 5 classes – nine and ten year-olds). Teachers had attended a series of professional learning sessions where they discussed the ideas and practices of dialogic pedagogy, learnt how visual texts can be used to promote discussion, and explored the central cultural values informing the project. In the DIALLS programme, lesson objectives prioritising the development of dialogue skills were positioned alongside the cultural themes to be discussed. These objectives were cumulative, focusing on listening and sharing ideas, in addition to building on arguments or disagreeing by offering alternative perspectives. Children’s awareness of their dialogic engagement was foregrounded. Importantly, the discussion topics were designed to be open-ended and to offer opportunities for multiple perspectives to be shared, rather than as debates to seek agreement.

Each class was observed twice at different points in the DIALLS programme (lesson 3 and lesson 8). The data include different contexts for learning – both whole class (WC) where teachers were leading the discussions (for the Y1 and Y5 lessons) and small groups (SM) where students worked with their peers (in Y5). Lessons were video and audio-recorded and transcribed – and the speech turns were coded as part of a wider project scheme analysing the interactions of students and teachers. The coding was used to identify instances where elaborations (which included both reasoning and expansions of this) occurred, following Howe et al. (Citation2019) conclusions about the importance of elaboration in productive educational dialogue. Here the unit of analysis was the student turn. Turns where students elaborated on each other’s contributions were isolated as indictors of a commitment to dialogue, that is, a desire to engage with multiple perspectives and tolerate the ambiguity that results from a lack of clear, agreed final positions. Inter-rater reliability was established across the team of researchers as each coded the transcripts separately, then compared differences and discussed these until a consensus was reached. Further linguistic analysis focused on the language of provisionality, capturing the frequency of words associated with suggestion/proposal or tentative ideas across the two lessons. These words were drawn from similar studies investigating discourse features (Boyd and Kong Citation2017; Maine Citation2015; Soter et al. Citation2008).

Following this initial, broad analysis, episodes of dialogic talk from the classes were qualitatively analysed to present a more refined picture of how a culture of dialogic practice was being enacted through language. This analysis followed a, ‘layered and iterative analytic process … zooming in on the event to investigate interactional details’ (Lefstein and Snell Citation2014, 186). The unit of analysis here was expanded to sequences of turns that indicated dialogic spells (Nystrand Citation1997).

In the project, ethical consents to record and transcribe classroom talk were given by parents/carers with the older children also signing their consent. Clear protocols for the collection, anonymisation, storage and sharing of data were followed (BERA Citation2018) and ethical approval was confirmed by the supporting university. To avoid assumptions made, for example, about the ethnicity of children indicated by naming/providing pseudonyms, the transcripts presented in the following section anonymise the children by giving them a number and G or B to indicate if they were a boy or a girl. The teacher is noted as ‘T’.

Findings and discussion

The wider lens

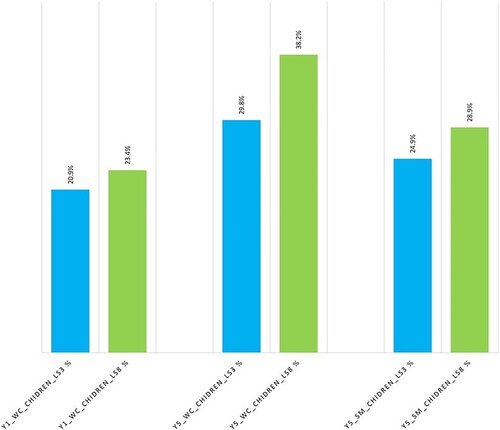

The linguistic analysis of the lessons showed that in all learning contexts (WC in Y1, WC in Y5, SM in Y5) there were differences in the percentage frequency of turns that included ‘elaborations’ (see ), that is, where children offered reasoning which they expanded appeared. shows the percentage frequency of this elaboration coding as it occurred in the wider coding scheme (which also captured, for example, statements, acknowledgements, invitation and managerial moves).

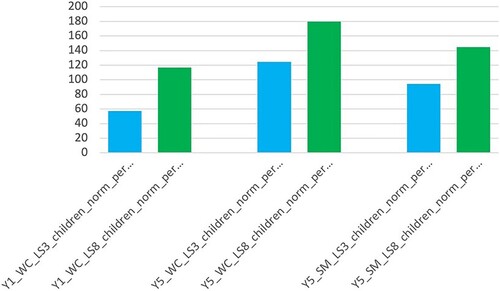

The graph shows a higher frequency of elaboration in the latter lesson for each different learning context. However, as each discussion and text was different in these lessons, a number of variables could have affected this (for example, if the discussion topics were more inviting, or if the texts themselves appealed more to the children). Thus, interpreting these results as an improvement over time should be circumspect. However, when set alongside an analysis of the frequency (normalised per 10,000 words) of provisional language words used by the children in the same contexts (), a clearer pattern is apparent, with elaborations and provisionality similarly changed in each context.

The combination of these two quantitative analyses indicates that reasoning and provisionality appear to work together in discussions where children are encouraged to explore multiple perspectives. However, this very broad analysis is not sufficient to understand how the language in these discussions works as a dialogic tool to encourage and engage multiple perspectives. For this, a close-up analysis of the language in use sheds light on the dialogic dynamic in the classroom, moving from a linguistic perspective to an ethnographic one.

The close-up lens

Researchers investigating classroom interaction have highlighted the limitations of looking at speech acts in isolation (see for example, Bloome et al. Citation2005; Rajala, Hilppö, and Lipponen Citation2012), and the affordance of a linguistic ethnographic approach is to use the wider analysis of patterns of language to isolate episodes for further interrogation. As the aim of the study was to look at the building of dialogic classrooms through language use, this analysis also focused on the teachers’ interactions to examine how they were modelling the enactment of the social value of dialogue in the two different year groups.

In the first episode, a class of Y1 children with their teacher are exploring a wordless picturebook which highlights issues of inclusion and solidarity. In Mein Weg mit Vanessa (Kerascoët Citation2018) a young girl is depicted starting at a new school, but on her way home is bullied by another child. A peer who has noticed the incident resolves to help out and the next day walks with her to school. In this episode, the class teacher is encouraging the children to share their interpretations of the images so that they can collaboratively construct the narrative.

Episode 1: Y1 whole class discussion about Mein Weg mit Vanessa

In each of her interactions with the three children, the teacher reaffirms what each is saying, to recognise that she has heard them and is basing her invitation for them to elaborate on their response on what they have already said. In response to her initial invitation, G1 offers her interpretation of the images and the teacher invites other children to link to her statement. This prompts G2 to offer a more extended elaboration (L52) and to refine her answer. However, this just prompts a one-word answer. The teacher acknowledges it and moves on. In the teacher’s interaction with G3, she more directly asks her to justify her reasoning. As a response (L58), the teacher offers her own elaboration on the action depicted. This short episode illustrates several of the dialogic teaching principles proposed by Alexander (Citation2020). The learning is framed as a collective endeavour with the teacher positioned alongside the children as the co-construct the story. The supportive environment means that these six year-olds are confident to share their ideas and engage in an ‘elaborative interrogation’ (Nystrand Citation2006, 397). The talk is purposeful and cumulative, as the goals of interpreting the text together are clear and coherent.

In the second illustrative episode, a Y5 class is discussing the concept of ‘home’ and what that might mean. It is a whole class (WC) discussion that demonstrates an inclusive environment where the children take an active stance in the management of the discussion. At the point of the episode that follows, the discussion has moved on to consider what it feels like to be displaced from home by war, a direction likely influenced by the class’s history topic about World War II. The episode is fragmented with overlapping speech (denoted by squared brackets) and ideas that start but remain unfinished. It is chosen because it reflects the reality of a whole class discussion where many voices are clamouring to be heard, where ideas are being presented as ‘thinking in action’ (Maine and Čermáková Citation2023) rather than as individual presentations of fully formed argument.

Episode 2: year 5 whole-class discussion about ‘home’ and displacement

There are several features of this extended exchange to highlight, if regarding it as indicative of a classroom discussion where dialogue is valued and multiple perspectives encouraged. The management of a whole class discussion to be more than simply the statement of ideas is a challenge. In this classroom, the teacher steps back from being the conduit through which all comments must pass and joins in the discussion to offer ideas alongside the children. Sometimes she overtly disagrees with the children (L468) and sometimes her voice is also unsuccessfully competing for the floor (L477). She allows the children to lead the discussion, and lines 458–466 show a sequence where, with good humour apparent from the whole class, the issue of overlapping speech occurs. Rather than take the reins and decide who should speak first, the teacher passes the responsibility to the speakers. The children are supportive of each other; in the episode between L473 and L478, G8 and G7 explore an alternative perspective. The final comment in the sequence returns to G4, who raised the point to begin with. She demonstrates how she has listened to the views of the others, and realising that it is not a simple decision to stay or go in times of war, has adjusted her position slightly.

The third illustrative episode shows a small group (SM) discussion that comes from the same Y5 lesson. The extract is from an earlier part of the lesson where the children are still discussing the concept of home and its multiplicity (Maine et al. Citation2021). It shows that the same patterns of involvement are evident in the small group as the whole class. The children share ideas, respond to each other and invite each other to contribute.

Episode 3: Y5 small group discussion about home and displacement

In this discussion the children try to link to each other’s ideas (L427, L431). They try to follow a thread to discuss the possibility that home might be more than just where you live. Here, as they stumble through an idea they are not sure of, there is more tentative language, with repetition and vagueness evident (‘kind of like’, ‘yeah’). These hedging words and phrases give the children space to construct their ideas as attempt to build cohesion. They are indicative of a collective goal, and also highlight the support the children give to one another.

An examination of high levels of exploratory talk (Mercer et al. Citation1999) might dismiss both Y5 discussions as the children largely agree with each other and incorporate each other’s views into their own, without neat positioning or scientific agreement. However, if the goal of the talk is also to nudge towards new thinking and ideas, including voices and respecting viewpoints, then expressing ideas in this way is valid. There are not simple answers to questions like, ‘Can you feel that two places are your home?’ and ‘How long does somewhere you no longer live remain your home?’ yet they are important concepts to consider in a time where displacement and isolation are the lived experiences of millions of people.

In both classes, the inclusion of different viewpoints and supportive sharing of ideas are enabled by the teachers. Sometimes this is explicit and the teacher draws the children’s attention to how they are developing ideas, or they model agreement and disagreement. Sometimes it is the lack of teacher domination in a discussion that indicates the underpinning principles of inclusion in the learning space. All three episodes are reminders that communities of learning take time to establish, and perhaps if children experience this throughout their primary education then they will be sophisticated dialogic learners as they head into secondary school.

Conclusion

This article has presented policy, research literature and examples of dialogue in practice to highlight the role of language in dialogic primary classrooms. These three strands now come together to point a way forward for the inclusion of dialogue in primary education.

The policies of the two educational jurisdictions of England and Wales can be seen to reflect the different models of literacy proposed by Street (Citation1984, Citation2003). From an autonomous perspective oral language can be seen as a set of decontextualised skills to be taught and mastered. For example, in England, the teaching of oral language skills is positioned to prioritise the presentation of reasoning and the expression of ideas using formal registers (Department for Education Citation2013). However, this offers only part of the purpose and potential of talk when it happens in a dialogic classroom. The wider potential of dialogue as bound together with culture, identity and understanding of oneself and community are reflected in the Curriculum for Wales (Welsh Government Citation2021). These ideas are more closely associated with Street’s ideological model of literacy as a social practice (Citation1984; Citation2003). Other educational jurisdictions follow similar approaches. A third project country, Finland, also positions ‘cultural competence, interaction and self-expression’ as transversal competences (FNAE Citation2016) that are needed in a changing society, thus moving the emphasis from individual understanding of identity and heritage into a societal competence.

The empirical data presented in the article show how dialogic classrooms, where the underpinning dispositions of tolerance, empathy and inclusion are foregrounded, can bring together these different curricula positions by supporting both the development of oral language skills and the development of dialogic competences. Firstly, the data show that in discussions that were opened-ended and focused on the exploration of different perspectives, provisionality and vagueness was embedded within the expression of ideas and reasoning. Secondly, in these classrooms, emphasis was not only on the presentation of ideas, the product, but on ‘thinking in action’, the process of collaborating and creating new thinking (Maine and Čermáková Citation2023). Teachers enabled this through careful modelling, affirmation and gentle challenge in Y1 and then through creating learning contexts where children could share their ideas about societal and cultural challenges in whole class and small groups in Y5.

The data shed light on the theoretical positions explored in the article, showing how dialogic pedagogy is enacted in practice, and how modes of language such as provisionality provide spaces for the development of ideas in shared learning environments. The examples show that language in the dialogic classroom can be a powerful, collaborative learning tool that serves a social purpose towards building intercultural competence and understanding of others with empathy and inclusion. The OECD goals for global competence highlight the need for individuals to, ‘engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions across cultures’ (Citation2018, 8). They define such interactions as, ‘relationships in which all participants demonstrate sensitivity towards, curiosity about and willingness to engage with others and their perspectives’ (Citation2018, 10). These goals can be realised through more explicit positioning of language and dialogue in curriculum policy, to incorporate not only oral language skills, but also the dispositions that underpin dialogue as a social and cultural practice, enabling and inspiring young people to be empathetic and inclusive in their engagement with each other and with the wider world.

Rights retention statement

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Acknowledgements

The DIALLS project (DIALLS Citation2021) was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme between 2018 and 2021, under grant agreement no. 770045. Further acknowledgement goes to Anna Čermáková for her corpus linguistic skills in extracting the original quantitative data from the DIALLS dataset.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alexander, Robin J. 2008. Towards Dialogic Teaching: Rethinking Classroom Talk. 4th ed. London: Dialogos.

- Alexander, Robin. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. 1st ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351040143.

- BERA. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th ed. London: BERA. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online.

- Bloome, David, Stephanie Power Carter, Beth Morton Christian, Sheila Otto, and Nora Shuart-Faris. 2005. Discourse Analysis & the Study of Classroom Language & Literacy Events: A Microethnographic Perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Boyd, Maureen P., Ming Ming Chiu, and Yiren Kong. 2019. “Signaling a Language of Possibility Space: Management of a Dialogic Discourse Modality Through Speculation and Reasoning Word Usage.” Linguistics and Education 50:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.03.002.

- Boyd, Maureen, and Yiren Kong. 2017. “Reasoning Words as Linguistic Features of Exploratory Talk: Classroom Use and What It Can Tell Us.” Discourse Processes 54 (1): 62–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2015.1095596.

- Buber, Martin. 1947. Between Man and Man. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Cambridge Primary Review. 2009. Introducing the Cambridge Primary Review. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

- Cook, Victoria, Fiona Maine, and Anna Čermáková. 2022. “Enacting Cultural Literacy as a Dialogic Social Practice: The Role of Provisional Language in Classroom Talk.” London Review of Education 20 (1): 14. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.20.1.02.

- Copland, Fiona, and Angela Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. 1st ed. London: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473910607.

- Council of Europe. 2018. “Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture - Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture.” https://rm.coe.int/prems-008318-gbr-2508-reference-framework-of-competences-vol-1-8573-co/16807bc66c.

- Department for Education. 2013. The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document. London: HMSO. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf.

- Dewey, John. 1933. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. New edition. Boston, MA: D. C. Heath and Company.

- DIALLS. 2021. https://dialls2020.eu/.

- Donaldson, Margaret. 1978. Children’s Minds. London: Harper Collins.

- Education Endowment Foundation. 2017. “Dialogic Teaching.” EEF. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/dialogic-teaching/.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2016. “National Core Curriculum for Primary and Lower Secondary (Basic) Education.” FNAE. https://www.oph.fi/en/education-and-qualifications/national-core-curriculum-primary-and-lower-secondary-basic-education.

- Hammersley, Martyn. 2007. “Reflections on Linguistic Ethnography.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00347.x.

- Hardman, Jan. 2019. “Developing and Supporting Implementation of a Dialogic Pedagogy in Primary Schools in England.” Teaching and Teacher Education 86:102908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102908.

- Hennessy, Sara, Sylvia Rojas-Drummond, Rupert Higham, Ana María Márquez, Fiona Maine, Rosa María Ríos, Rocío García-Carrión, Omar Torreblanca, and María José Barrera. 2016. “Developing a Coding Scheme for Analysing Classroom Dialogue Across Educational Contexts.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 9:16–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.12.001.

- Howe, Christine, Sara Hennessy, Neil Mercer, Maria Vrikki, and Lisa Wheatley. 2019. “Teacher-Student Dialogue During Classroom Teaching: Does It Really Impact on Student Outcomes?” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 28 (4-5): 462–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1573730.

- Kerascoët. 2018. Mein Weg Mit Vanessa. Hamburg: Aladin Verlag.

- Lefstein, Adam, and Julia Snell. 2014. Better Than Best Practice: Developing Teaching and Learning Through Dialogue. 1st ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315884516.

- Lefstein, Adam, Julia Snell, and Mirit Israeli. 2015. “From Moves to Sequences: Expanding the Unit of Analysis in the Study of Classroom Discourse.” British Educational Research Journal 41 (5): 866–885. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3164.

- Maine, Fiona. 2015. Dialogic Readers: Children Talking and Thinking Together About Visual Texts. London: Routledge.

- Maine, Fiona, Benjamin Brummernhenrich, Maria Chatzianastasi, Vaiva Juškienė, Tuuli Lähdesmäki, Jose Luna, and Julia Peck. 2021. “Children’s Exploration of the Concepts of Home and Belonging: Capturing Views from Five European Countries.” International Journal of Educational Research 110:10187: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101876.

- Maine, Fiona, and Anna Čermáková. 2021. “Using Linguistic Ethnography as a Tool to Analyse Dialogic Teaching in Upper Primary Classrooms.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 29:100500: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100500.

- Maine, Fiona, and Anna Čermáková. 2023. “Thinking Aloud: The Role of Epistemic Modality in Reasoning in Primary Education Classrooms.” Language and Education 37 (4): 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2022.2129979.

- Maine, Fiona, Victoria Cook, and Tuuli Lähdesmäki. 2019. “Reconceptualizing Cultural Literacy as a Dialogic Practice.” London Review of Education 17 (3): 383–392. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.17.3.12.

- Mercer, Neil, Rupert Wegerif, and Lyn Dawes. 1999. “Children’s Talk and the Development of Reasoning in the Classroom.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (1): 493–516.

- Nystrand, Martin. 1997. Opening Dialogue: Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning in the English Classroom. Language and Literacy Series. London: Teachers College Press.

- Nystrand, Martin. 2006. “Research on the Role of Classroom Discourse as It Affects Reading Comprehension.” Research in the Teaching of English 40 (4): 392–412. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte20065107.

- OECD. 2018. Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World the OECD PISA Global Competence Framework. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/Global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world.pdf.

- Rajala, Antti, Jaakko Hilppö, and Lasse Lipponen. 2012. “The Emergence of Inclusive Exploratory Talk in Primary Students’ Peer Interaction.” International Journal of Educational Research 53 (January): 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.12.011.

- Rampton, Ben. 2007. “Neo-Hymesian Linguistic Ethnography in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 584–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00341.x.

- Rapanta, Chrysi, Dilar Cascalheira, Beatriz Gil, Cláudia Gonçalves, D’Jamila Garcia, Rita Morais, João Rui Pereira, et al. 2021. “Dialogue and Argumentation for Cultural Literacy Learning in Schools: Multilingual Data Corpus.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4742176.

- Resnick, Lauren B., Christa S.C. Asterhan, and Sherice N. Clarke. 2018. “Accountable Talk: Instructional Dialogue That Builds the Mind UNESCO International Bureau of Education.” UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000262675.

- Rowland, Tim. 2007. ““Well Maybe Not Exactly but It’s Around Fifty Basically?”. Vague Language in Mathematics Classrooms.” In Vague Language Explored, edited by Joan Cutting, 79–96. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shady, Sara LH, and Marion Larson. 2010. “Tolerance, Empathy, or Inclusion? Insights from Martin Buber.” Educational Theory 60 (1): 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2010.00347.x.

- Soter, Anna O., Ian A. Wilkinson, P. Karen Murphy, Lucila Rudge, Kristin Reninger, and Margaret Edwards. 2008. “What the Discourse Tells Us: Talk and Indicators of High-Level Comprehension.” International Journal of Educational Research 47 (6): 372–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.01.001.

- Street, Brian V. 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture, 9. Cambridge: University Press.

- Street, Brian V. 2003. “What’s “New” in New Literacy Studies? Critical Approaches to Literacy in Theory and Practice.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 5 (2): 77–91. https://doi.org/10.52214/cice.v5i2.11369.

- Wegerif, Rupert. 2013. Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203111222.

- Wegerif, Rupert. 2018. “Dialogue and Equality.” Rupert Wegerif (blog). https://www.rupertwegerif.name/blog/dialogue-and-equality.

- Welsh Government. 2021. “Languages, Literacy and Communication: Introduction - Hwb.” https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/languages-literacy-and-communication/.

- Wolf, Mikyung Kim, Amy C. Crosson, and Lauren B. Resnick. 2006. Accountable Talk in Reading Comprehension Instruction. CSE Technical Report 670. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST). http://eric.ed.gov/?id = ED492865.