?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this empirical study was to investigate the antecedents and prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour in primary and middle-level schools of the state of Amhara, Ethiopia. A mixed approach with an embedded research design was employed. Multi-stage stratified sampling was applied to select 748 teacher respondents. One sample t-test, multiple regression and hierarchical multiple regression model were used to analyse the data. The study revealed that antecedents of destructive leadership were moderately exhibited in Primary and Middle-Level Schools. When the prevalence of destructive leadership was regressed on susceptible followers, leader behaviour and conducive environment antecedents of destructive leadership, 61% of the variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour was accounted for by the interplay of susceptible followers, leader behaviour and conducive environment. Leader behaviour antecedent of DLB contributes more to the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour among principals in primary and middle schools. Based on the findings of the study it is inferred that the antecedents of destructive leadership were moderately exhibited in the primary and middle-level schools of the study area.

1. Introduction

The problem related to destructive leadership is the level of understanding we have; due to the presence of imbalances in research between understanding the nature and consequences of positive leadership attributes and dysfunctional leadership attributes. That is why, Hogan et al. (1990) as cited in Burke (Citation2006) said that if we don't investigate the dark side of leadership, we won't be able to fully comprehend it. This suggests that in order to have a more accurate understanding of leadership, we must first examine its dark side.

To begin with, destructive leadership is defined as the systematic and recurring actions of a manager, supervisor, or leader that undermine and/or sabotage the organisation’s goals, tasks, resources, and effectiveness as well as the motivation, well-being, or job satisfaction of his/her subordinates. This behaviour violates the legitimate interest of the organisation (Einarsen, Aasland, and Skogstad Citation2007). According to Thoroughgood et al. (Citation2012), it is a leadership style exemplified by behaviours that are often seen as detrimental and abnormal towards followers and/or the organisation. It is a specific kind of wrongdoing that is unquestionably linked to the leader's voluntarily engaging in such activity. Destructive leadership behaviour, on the other hand, happens when a leader acts in a way that is actively or passively harmful to workers, organisations, or both, whether verbally or physically, in a direct or indirect manner. It does not, however, address behaviours that are the result of incompetence and/or good intentions (Buss 1961, as cited in Aasland et al. Citation2010).

Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, and Vohs (Citation2001) provided a foundational basis for this proposal by implying that bad occurrences have a higher impact on social interactions than positive ones and that bad events are more common than good ones. This suggests that in order to influence desired outcomes in an organisation, recognising and mitigating the bad parts of leadership may be just as important – if not more so – than recognising and developing its positive features. This again implies that educational policy and strategy aspirations of schools success without proper understanding and prevention of such leadership behaviour is impossible. Therefore, it was worthy to investigate the antecedents and prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour for the following reasons.

One thing, there is a dearth of research and a lack of understanding of the effects of toxic leadership in educational settings. Out of the dozen research done on school leadership, particularly in Ethiopia, nearly all of them concentrate on and highlight the positive aspects of leadership while ignoring its negative aspects. The work of Gunaseelan (Citation2016), who asserts that leadership has both a constructive and destructive side, provides literature support for this divide. In organisations, both are evident, but only the positive one seems to receive the most attention. Here, the level of incidence and contributing elements of destructive leadership were empirically investigated in light of the study's local context.

Second, a practical issue exists in the local setting of this research project, implying the existence of harmful leadership. At the level of the district education office, the researcher held the responsibility of supervising teachers, school principals, and supervisors. The researcher heard grieving teachers' comments at that time, accusing school administrators of misbehaving. Instructors frequently complained about their immediate school superiors' denigration, undermining, exploitation, abuse, unfair treatment, and punishment. Even the researcher had seen instructors who blamed the actions of their school principals for their transfer from a very comfortable school to one with inferior infrastructure. Typically, the researcher had experienced the presence of teachers who dislike their profession in general and working schools in particular blaming the behaviour of school leaders in front of them. Additionally, the researcher has seen several instructors who quit their jobs due to unfavourable leadership and a dislike of working with aggressive school administrators. Since there was no existing research-based information in the local context of this research problem, all of these obvious implications to the existence of practical issues with destructive leadership behaviour in the research study's local context demand empirical verification.

Third, as another implicate of the leaders DL behaviour, once upon a time one school principal who the researcher knows' stole ‘21,000’ Ethiopian birr and disappeared from the school. That man today is the reach person who lives in the country without any accountability. In fact MoE (Citation2018) reported a broad gap that accountability is missed at all levels of the education governance. This strongly supports the researchers' experienced problem at the very ground. In this case, theft is one manifestation of destructive leadership behaviour and unable to ensure accountability in the system will serve as a fertile ground to develop such a behaviour, but needs an empirical investigation. At the very beginning, based on the researchers' experience, principals were striving to hold the principal-ship position for a priory to gain a better salary than to lead and bring change to schools. School principals were finding it difficult to prioritise their own change over that of the school. Kellerman (Citation2004) defined them as harmful leaders in literature, referring to leaders like school administrators who prioritise their personal interests over the organisation's genuine goals.

Therefore, the main purpose of this research was to investigate the antecedents, and prevalence of destructive leadership in the case of primary and middle-level schools. Accordingly, the study answered the following research questions:

To what extent the antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour are exhibited in the primary and middle schools of the state of Amhara?

How much of the variance in destructive leadership behaviour prevalence can be explained by each antecedent in the current study area?

Which antecedent contributes more to the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour among principals in the primary and middle schools of the state of Amhara?

2. Conceptual framework of the study

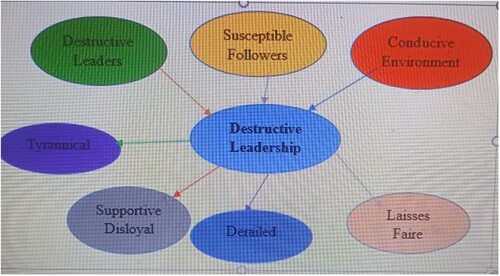

The centre of gravities to develop a conceptual framework for this research study were antecedents to destructive leadership (3 at the top), destructive leadership prevalence (1 at the centre), and destructive leadership dimensions (4 below). The overall development of this conceptual framework is guided by the toxic triangle model forwarded by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) and the destructive leadership model developed by Einarsen, Aasland, and Skogstad (Citation2007).

At the very beginning, the toxic triangle model forwarded by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) suggested that destructive leaders do not exist in a vacuum; rather the model defines destructive leadership along the interaction effect of the leaders, followers, and environmental contexts. Based on this, the three elements such as destructive leaders, susceptible followers and a conducive environment as a prior thing for the existence of destructive leadership was framed to have a direct linkage with destructive leadership prevalence at the centre. Therefore, in this research problem, the researcher is looking forward to empirically test as if the (toxic triangle elements) antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour were exhibited inside the primary and middle-level schools of the given local context.

The destructive leadership model developed by Einarsen, Aasland, and Skogstad (Citation2007) describes destructive leadership behaviour along four dimensions; destructive leader behaviours targeting the followers (tyrannical), destructive leader behaviours that target the organisation (supportive-disloyal), behaviours targeted to both (derailed) and passive destructive leadership behaviour (lasses faire). For this research problem, this conceptualisation can be used so that it would help to see the level of existence (prevalence) of destructive leadership and various manifestations (dimensions) of destructive leadership as reflected in the framework.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study design and paradigmatic instance

This study followed the positivist paradigm because the nature of this study is investigating the effect of destructive leader behaviour, susceptible followers and conducive environment on the prevalence of destructive leadership properly aligns with the attribute of the positivist paradigm. Hence, the concept of the positivist paradigm satisfied the current study. To deal with in detail, this study intends to test the effect of destructive leader behaviour, susceptible followers and conducive environment on the prevalence of destructive leadership through a purely quantitative view. After deciding the paradigm that the researcher followed, the next step was selecting the appropriate design that satisfied the study. Therefore, based on the nature of the study conducted, the predictive design was selected. The argument that urges the researcher to select predictive design is that predictive studies explain the predictions of a well-defined problem through a number of variables believed to be related to a big and complex variable. As a result, the researcher investigated the predictive effect of destructive leader behaviour, susceptible followers and conducive environment on the prevalence of destructive leadership using a predictive research design.

3.2. Population and sample

Based on Amhara National Regional State Education Bureau Annual Education Statistics Abstract (2020/2021), there are 5769 primary and middle-level schools and 50,138 (33,128 Male & 17,010 Female) teachers, 5769 (8359 male and 589 female) principals, 1,509 (1056 male and 453 female) vice principals and 1999 (1,912 male and 87 female) cluster supervisors in the region that can be considered as the population to this study. The state of Amhara is decided as a study area to be considered intentionally. Because the problem of this research study was framed based on the researcher's own experience. From 15 (fifteen) zones of the study area representative sample 30%s (5) zones were randomly selected using a simple random sampling technique of a lottery system. A multi-stage stratified sampling technique followed by convenient sampling was also applied to select appropriate sample units and participants proportionally.

To determine the proportional sample size of respondents Cochran formula was used.

The Cochran formula is;

where: e is the desired level of precision (i.e. the margin of error); p is the (estimated) proportion of the population which has the attribute in question; q is 1 − p, and the z-value is found in a Z table.

Therefore, in this study, the researcher assumed that half of the study population shares the same attribute that gives the maximum variability. So p = 0.5. The researcher wants 95% confidence, and at least 5 percent plus or minus precision. A 95% confidence level gives Z value of 1.96, per the normal tables. Therefore by computing the above Cochran formula the researcher gets; ((1.96)2 (0.5) (0.5)) / (0.05)2 = 385.

This is true when the population size (amount) is infinite or not known. But in cases when the population size is finite and known the reduced formula will be used. For this study, the total population is 17,795, hence the researcher used the reduced Cochrans' formula;

where, n0 is Cochran's sample size recommendation, N is the population size, and n is the new adjusted sample size. Therefore; n = 377.

Finally, the design effect is calculated as; N = D X n, where N is the design effect, D is the stages in the multi-stage stratified sampling and n is the adjusted sample size. N = 2 × 377 = 754. So, a random respondent of 754 teachers in all sample study woreda was taken as a respondent to the survey.

3.3. Instrumentation

To measure the antecedents of destructive leadership (leader behaviour, susceptible follower and conducive environment respectively); the toxic leadership scale developed by Schmidt (Citation2008), the Alvarado work environment scale of toxicity developed by Alvarado (Citation2016) and follower susceptibility scale developed by Christian N. Thoroughgood (Citation2013) was adopted.

Again a destructive leadership scale developed by Einarsen et al. (2002) as cited in Hayson (Citation2016) and a lasses fair leadership questionnaire from a multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio (1990), were also adapted to measure the prevalences of destructive leadership behaviour.

On the other hand, the instrument used to measure turnover intention was adapted from turnover intent (TI) questionnaire derived from a survey created by Mobley et al. (1978) and Roodt's (2004) unpublished turnover intention scale as cited in Bonds (Citation2017).

3.4. Data analysis

The SPSS version 26 application was used for data analysis purposes. The gathered data were coded, cleaned up, and then preliminary analysis (looking for multivariate outliers, missing values, and verifying multivariate assumptions) was performed. To investigate whether there is a significant association between teachers' intention to leave their jobs and principals' destructive leadership style, Pearson correlation analysis was used. The variance in teacher turnover intention that can be explained by each destructive leadership behaviour dimension was found using multiple regression, and the destructive leadership behaviour dimension that contributes most to teachers' turnover intention was found using hierarchical regression.

3.4.1. Demographic profile of respondents

The demographic details of the respondents who took part in answering the survey are displayed in the following tables. The sex of the respondents is the subject of , the bellows table. A total of 748 persons were included in this research as the survey questionnaire respondents, as indicated in the table above. According to the demographic data, 67% of all respondents were female and the remaining 33% were male. This indicates that the majority of respondents were female. Because the question was administered at random, there were more female participants than male participants in terms of share. This discrepancy is insignificant because the study's intended purpose was not to investigate gender-based perceptual differences regarding the title's study variables. It does, however, have implications for future research in the field, particularly with regard to the existence of perception and intention differences regarding turnover intention and destructive leadership conduct, respectively, between males and females ().

Table 1. Sex of respondents.

In terms of responder age, the majority of teacher participants in this study – 81.1% – were between the ages of 25 and 50. The remaining 7.1% and 11.8% of teachers who responded were under 25 and over 50 years old, respectively. The majority of primary and middle school teachers who responded to this survey may have reached the appropriate level of maturity for their age, based on the results. They also provided reliable information about the behaviours of school administrators and made it clear whether or not they intended to leave their jobs or continue working in schools. This result may also encourage other researchers to conduct a follow-up study in the area, focusing on the existence of age-related perception differences regarding teachers' intentions to leave their jobs and/or damaging leadership behaviour (among different age groups) ().

Table 2. Age of respondents.

According to below, which shows the credentials of the teacher respondents, the majority of the teachers (60.6%) were diploma holders; the remaining 1.7% and 37.7% of respondents were certificate/below and degree holders, respectively. In terms of teaching experiences, the majority of survey participants – 67.2% – have more than ten years of experience. In contrast, the remaining teacher respondents – 8.4% and 24.3%, respectively – have less than or equal to five years of experience and between six and ten years of experience. Even though the majority of the teacher participants held diplomas, it's possible that most of them had enough experience working as elementary and middle school teachers to be able to provide reliable information on the problem being investigated. This discovery also carries implications for future research about the existence of perception differences regarding damaging leadership behaviour among educators with different backgrounds and experiences in the classroom. If instructors' intentions to leave vary amongst those with different backgrounds and experiences, that has further implications for future research.

Table 3. Educational status and experience of respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour

One of the primary research goals of the study was to ascertain the extent to which primary and middle schools exhibited the precursors of destructive leadership. This was accomplished by using the toxic triangle model created by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) to assess the extent to which harmful leadership antecedents were evident. Three elements of the model – permissive surroundings, vulnerable followers, and destructive leaders – were considered as antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour.

shows the three major subscales where the demonstrated level of antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour was examined. The respondents' perceived average mean perceptions for susceptible followers, conducive environment, and leader behaviour were found to be x̄ = 3.15, x̄ = 3.06, and x̄ = 3.24, respectively. It was also discovered that the respondents' cumulative average mean perception of the causes of damaging leader conduct was 3.15. This demonstrates unequivocally that none of the major scales mean reached a scale of four, which indicates agreement in the individual items. Instead, the cumulative mean values of the antecedents of destructive leadership behaviour in three of the major dimensions are closer to a scale of three, which indicates agreement to some extent in the individual questionnaire items (moderate level of existence to the analysis). Therefore, the overall outcome shows that the primary and intermediate-level schools in the study area had modestly displayed DLB antecedents.

Table 4. The mean perception values of antecedents of destructive leadership.

Examining the variation in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour that may be explained by each of the DLB antecedents and determining which antecedent contributes more to the prevalence of DLB was the second main study topic.

All variables were checked for significant statistical assumption violations, such as normality, linearity, multi-collinearity, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals, before moving on to the data analysis for this research question, and the data model satisfied all the requirements. The database was first examined for accuracy in data entry, extreme and missing values using frequency distribution, and the minimum and maximum scores for each variable. These checks revealed no issues with outliers or missing values. The data points were reasonably close to the straight line, and the data model satisfies the assumption that the residuals should be normally distributed about the anticipated DV scores, according to graphical analyses of the data's normality using the Q-Q plot and histogram. Each variable's linearity was also evaluated using a normal probability plot, and none of the study's variables clearly demonstrated a tendency towards linearity based on the probability plot (normal Q-Q plot). As a result, the data model satisfies the requirement that the residuals and anticipated DV scores have a straight-line connection. Another assumption taken into account was multi-collinearity. When the independent variables have a strong correlation (r = .9 and above), multi-collinearity is present. Once more, a tolerance value less than 10 or a VIF more than 10 denotes a multi-collinearity issue. As a result, multi-collinearity among the variables in the analyses did not appear to be an issue in this study, as evidenced by the appendix previously indicated, where all tolerance values >.1 and VIF < 10. Using a scatterplot, which showed that the standardised residuals were nearly rectangular distributed with the majority of the scores concentrated in the middle, the homoscedasticity assumption was also checked and found to be met. Durbin-Watson was used to complete the second assumption of the Independence of Residuals Test. Durbin-Watson test statistic scores between 1.5 and 2.5 are generally considered to be very normal. However, values outside of this range can be reason for worry (Will Kenton Citation2023). This study's Durbin-Watson statistic test value was 1.9, indicating a satisfactory model fit. Overall, the current data met the conditions of normality, linearity, multi-collinearity, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals test. It was determined that the data were suitable for the multiple regression analysis as a result.

4.2. The predictive relationships between antecedents and prevalence of DLB

In this case, hierarchical multiple regression and multiple linear regression were conducted one after the other. Hierarchical regression analyses were performed to determine which antecedent of destructive leadership predicts more in the model for the variation in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine the extent to which each antecedent of destructive leadership explained the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour independently.

R: 0.780.

R Square: 0.609.

Adjusted R Square: 0.607.

shows that all predictor variables (i.e. conducive environment, leader behaviour, and susceptible followers) explained significantly and positively the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour. The results are as follows: β = .18, p < 0.001 for conducive environment, β = .39, p < 0.001 for leader behaviour, and β = .29, p < 0.001 for susceptible followers. Using this data model, it was possible to determine that the interaction between conducive environment, leader behaviour, and susceptible followers explained 60.9% of the variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour when the behaviour was regressed on these variables. Therefore, the interaction of each DLB antecedent can account for 61% of the variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour.

Table 5. The result of multiple regression analysis predicting prevalence of destructive leadership from its antecedents.

Hierarchical regression was used to determine which antecedent contributes more to the prevalence of DLB and how much each antecedent affects destructive leadership behaviour. demonstrates how all of the damaging leadership antecedents were arranged hierarchically in the regression equation according to their beta weights, with leader conduct accounting for the majority of the model's variation. The variable in question accounted for 51.1% of the variation in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour, and it demonstrated statistical significance (F (1,745) = 778.62, p < 0.001). The second most significant predictor variable in the model that was included in the regression equation was susceptible followers. The addition of this variable resulted in an 8.5% statistically significant increase in the proportion of variation in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour (F (2, 744) = 549.81, p < 0.001). The inclusion of the conducive environment as the final predictor in the regression equation resulted in a 1.3% increase in the proportion of variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour, which was nevertheless statistically significant (F (3, 743) = 385.87, p < .001). Hence, the DLB model benefits more from the leader behaviour antecedent.

Table 6. The result of hierarchical regression analysis predicting destructive leadership prevalence from its antecedents.

5. Discussion

Examining the degree to which DLB antecedents are demonstrated was one of the research questions in this study. It was established that all three of the prerequisites for destructive leadership – a destructive leader, gullible followers, and a supportive environment – were only mildly present. Qualitatively, it is also shown that in elementary and middle schools, the antecedents of harmful leadership conduct were teachers' cooperation, the competency and experience of leaders, their inherent character, and the system's inability to ensure accountability. This result is in line with Orunbon's empirical research (Citation2020), which showed that in a school context, toxic leaders frequently have more freedom to express their toxicity due to vulnerable followers and a supportive environment. Schneider’s (Citation2021) empirical research corroborated the conclusion that the environment has a significant role in the manifestation of destructive leadership in organisations, in addition to the psychological attractiveness of destructive leaders. Pelletier, Kottke, and Sirotnik (Citation2019) discovered evidence for the environment and susceptible followers prior to damaging leadership, which is consistent with the study's findings.

Similarly, research by Thoroughgood et al. (Citation2012), who claim that disruptive leaders – like leaders in general – do not act in a vacuum, supports the findings of this study. The results of this study confirmed the veracity of the aforementioned claim by illuminating the demonstrated spirit of predisposing followers, poisonous leader behaviour, and favourable surroundings.

The story of Baronce (Citation2015), who examined the work of Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007), provides support for the current study's findings. Baronce stated that the idea behind the toxic triangle is not that followers are toxic, but rather that there is a toxic leader who causes bad things to happen because of their actions, decisions, and behaviour. The toxic leader is surrounded by followers who because they lack the strength to resist anything potentially hazardous and because the atmosphere encourages the growth of toxicity, are likely to allow the toxicity to spread. Therefore, followers may act in a way that encourages toxicity and has detrimental long-term effects, just like toxic leaders do. Baronce stated that toxicity is influenced by the environment, which lends additional credence to the current findings. Politicians and other leaders utilise natural or man-made disasters (financial crises, wars, political messiahs, etc.) to their advantage in order to enact laws that are less beneficial to the populace but grant them greater authority and influence. They take advantage of people's fragile mental states by acting as poisonous leaders. This hypothesis clarified that when followers believe that things are out of control, they are more inclined to agree to follow. Sadly, the actual condition of affairs at the time of the study was one of manufactured disasters (war), and the study's findings are in line with the literature mentioned above, which establishes the foundation for destructive leadership's manifestation. Because they believe that things are out of control, teachers in the study's target area, for example, are more likely to embrace and obey such harmful school leaders.

The existence of a supportive environment where ‘instability, perceived threat, cultural values, absence of checks and balances and institutionalisation destroys the natural order of the situation and contributes for the destructive leadership behaviour’ is disclosed by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) as additional support for the findings of the current study. The real environmental setup of the subject area in this study can be described as unstable, filled with perceived threats, a setting where people do not feel free, and lacking in checks and balances. Therefore, the general environmental condition of the research area – a disordered environment that promotes toxicity – may be the cause of the demonstrated precursors of destructive leadership established in the schools of the current study. According to this study, there is no reason why instructors at the school shouldn't feel insecure or fearful of what will happen the next day in the actual environment of Ethiopia as a whole, and the state of Amhara in particular. As a result, they may collaborate with leaders to take harmful actions.

The results of this study also align with the research conducted by Lipman-Blumen (Citation2005), which claimed that people support and prefer disruptive leaders in a variety of industries, including public non-profit education. People do not just tolerate harmful leaders. This suggests that followers themselves encourage and assist leaders to act destructively before leaders act in a harmful manner and followers accept such a behaviour. The present study's findings from the qualitative data analysis, which highlighted teachers' cooperation as one of the main preconditions for school leaders to exhibit damaging leadership behaviour, corroborate the aforementioned statement. It is recalled from the quantitative data analysis that vulnerable followers have shown detrimental leadership conduct as a precursor.

This study not only revealed receptive followers and a favourable atmosphere, but it also revealed that toxic leaders were the precursors of harmful leadership behaviour. This conclusion is further supported by the results of the qualitative data analysis, which showed that the study area's school leaders' aggressive, tyrannical, abusive, and thieving activities were examples of deviant leadership behaviours. This result is consistent with other scientific studies. For example, Kusy and Holloway (Citation2009) found that 64% of study participants said they were currently working under a toxic boss, suggesting that the leader was acting inappropriately at work. The results of this investigation are likewise in line with earlier empirical studies in the sector, including those by Solfield and Salmond (Citation2003), who revealed empirically that 91% of employees suffered verbal abuse that left them feeling embarrassed. According to (Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser Citation2007), the feature that most clearly identifies a toxic leader is their lack of ethics. The study's qualitative data, which supports this claim, demonstrated that school administrators do in fact engage in thieving behaviour. All of this suggests the extent to which poor leadership conduct is demonstrated at work, and the current study's findings are corroborated by and comparable to earlier empirical investigations in the field.

4.3. The predictive relationships between antecedents and prevalence of DLB

The incidence of destructive leadership behaviour was significantly and positively predicted by each of the three antecedents of destructive leadership – a permissive environment, susceptible followers, and leader behaviour. According to this study, the interaction of each antecedent of destructive leadership behaviour can account for 61% of the total variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership. 51.1%, 8.5%, and 1.3% of the total variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership was explained by the interactions between conducive environment, susceptible followers, and leader behaviour, out of the 61% of variance that was accounted for by these factors alone. The study's findings are supported by the toxic triangle model developed by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) to conceptualise the antecedents of destructive leadership. This model states that destructive leadership is defined as the unfavourable outcomes that arise from the combination of destructive leaders, vulnerable followers, and favourable environments.

Additionally, this study established that the antecedent destructive leadership conduct of a leader positively and significantly predicts the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour. The results are most in line with earlier empirical studies in the field. Destructive leadership begins when a ‘manager + leader’ ceases to be either a manager or a leader, according to Atan's (Citation2014) paper, Destructive Leadership: From Retrospective to Prospective Inquiry (Antecedents of Destructive Leadership). This suggests that leaders are the main forces behind the success of destructive leadership. According to Atan's empirical research, which was previously indicated, there are erratic, violent, conceited, corrupt, and evil leaders everywhere, and bad or at least undeserving individuals frequently hold prominent leadership positions. Byrne et al. (Citation2014) conducted a scientific investigation into the connection between leaders' depleted resources and their leadership behaviours, corroborating the findings of the current study. They found that leaders' depletion was linked to higher levels of abusive supervision. The current study's findings are corroborated by earlier empirical research by Dionisi and Barling (Citation2019), who discovered that conflict between family and work affects leaders' personal life and is linked to poor leadership conduct. A scientific work titled ‘The Hot and Cold in Destructive Leadership: Modeling the Role of Arousal in Explaining Leader Antecedents and Follower Consequences of Abuse versus Exploitative Leadership’ was produced by other researchers in the field, Emmerling, Peus, and Lobbestael (Citation2023). The current study's findings are corroborated by earlier empirical research by Dionisi and Barling (Citation2019), who discovered that conflict between family and work affects leaders’ personal life and is linked to poor leadership conduct. A scientific work titled ‘The Hot and Cold in Destructive Leadership: Modeling the Role of Arousal in Explaining Leader Antecedents and Follower Consequences of Abuse versus Exploitative Leadership’ was produced by other researchers in the field, Emmerling, Peus, and Lobbestael (Citation2023).

Once more, although the degree varies, susceptible followers are a prelude to harmful leadership. Owolabi’s (Citation2022) earlier empirical work in this area also lends weight to the study's findings. Using a quantitative method, Owolabi empirically explored the impact of followership traits (types) on destructive leadership behaviour. The findings showed that destructive leadership conduct was substantially correlated with followers' thinking and participation, accounting for 22.2% of the variance in destructive leadership behaviour. The results of this study support and are consistent with an empirical work by Owolabi that revealed a direct relationship between followership and destructive leadership. As previously mentioned, the amount of variance that susceptible followers explained on destructive leadership was actually different. The results of this study also aligned with earlier empirical research by Schaubroeck et al. (Citation2012), which discovered that 79% of leaders would never confront a superior who was acting unethically. This suggests that harmful leadership conduct would proliferate if followership vulnerability was present at work. Since followers are the ones who are constantly exposed to toxic behaviours, the results of this study align with the scientific work of Reed (Citation2004), who stated that followers have a key role to play in recognising toxic leaders. Reed suggested that by their blind obedience, gullible followers are the ones who support poisonous leadership. This suggests the degree to which the results of the current study, in which followers predict damaging leadership, were consistent with earlier research on the subject. The results of Thoroughgood et al. (Citation2012), who unequivocally asserted that followers are vulnerable to toxic leaders' impact, corroborate the findings of the current study. Because of this power imbalance between teachers and school leaders, it is possible that teachers in the study provided are more vulnerable to the influence of school leaders.

The context that accounts for the ubiquity of harmful leadership behaviour was the study's other key finding. The results showed that destructive leadership is positively predicted by a conducive atmosphere. The work of Erickson et al. (Citation2015), which revealed how the working environment itself positively predicts destructive leadership, supports this finding. They reported that organisational factors like high turnover, poor role modelling by senior management, or a dysfunctional culture are the cause of destructive leadership. The results of this investigation are corroborated by other earlier scientific studies. For example, Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (Citation2007) revealed that environments that are volatile, unpredictable, complex, and ambiguous are prone to foster the growth of toxic leadership. The reality that the area under study is extremely unstable and lacks a check and balance because of the uncertainty and volatile nature of the ground may have contributed to the study's result, which showed a positive prediction of a conducive environment in school leaders' destructive leadership behaviour.

5. Summery and conclusion

First of all to summarise the findings; as perceived by respondents, the antecedents of DLB were moderately exhibited in the primary and middle-level schools of the study area. When the prevalence of destructive leadership was regressed on susceptible followers, leader behaviour and conducive environment antecedents of destructive leadership, it was found that 61% of the variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour was accounted for by the interplay of susceptible followers, leader behaviour and conducive environment. The study also revealed that leaders' behaviour contributes more to the prevalence of DLB among principals in primary and middle schools.

Based on the findings of the study it is inferred that the antecedents of destructive leadership were moderately exhibited in the primary and middle-level schools of the study area. 61% of the variance in the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour was accounted for by the interplay of susceptible followers, leader behaviour and conducive environment. Leader behaviour antecedent of DLB contributes more to the prevalence of DLB among principals in primary and middle schools. This variable explained 51% of the variance in destructive leadership behaviour prevalence.

6. Implications

The study's conclusions have implications for future research on the causes of bad leadership behaviour, the susceptibility of followers, and the conditions that lead to bad leadership. They also have implications for the issue at other educational levels, including secondary schools and universities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their truthful thanks to the study participants for their consent and dedication of their time in providing data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aasland, M. S., A. Skogstad, G. Notelaers, M. B. Nielsen, and S. Einarsen. 2010. “The Prevalence of Destructive Leadership Behavior.” British Journal of Management 21 (2): 438–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00672.x.

- Alvarado, C. 2016. Environmental Ingredients for Disaster: Developing and Validating the Alvarado Work Environment Scale of Toxicity. San Bernardino: California State University.

- Atan, T. R. 2014. "Destructive Leadership: From Retrospective to Prospective Inquiry (Antecedents of Destructive Leadership)." Archives of Business Research 2 (6): 48–61.

- Bass, B. M., and B. J. Avolio. 2004. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Menlo Park.

- Baronce, E. 2015. From Passivity to Toxicity: Susceptible Followers in a Conducive Environment. Linnaeus University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:839156/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Baumeister, R. F., E. Bratslavsky, C. Finkenauer, and K. D. Vohs. 2001. “Bad Is Stronger Than Good.” Review of General Psychology 5 (4): 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323.

- Bonds, A. A. 2017. “Employees’ Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intentions.” Doctoral diss., Walden University.

- Burke, R. J. 2006. “Why Leaders Fail: Exploring the Dark Side.” International Journal of Manpower 27 (1): 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720610652862.

- Byrne, A., A. M. Dionisi, J. Barling, A. Akers, J. Robertson, R. Lys, J. Wylie, and K. Dupré. 2014. "The Depleted Leader: The Influence of Leaders' Diminished Psychological Resources on Leadership Behaviors." The Leadership Quarterly 25 (2): 344-357.

- Dionisi, A. M., and J. Barling. 2019. "What Happens at Home Doesn’t Stay at Home: The Role of Family and Romantic Partner Conflict in Destructive Leadership." Stress and Health. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2858

- Einarsen, S., M. S. Aasland, and A. Skogstad. 2007. “Destructive Leadership Behavior: A Definition and Conceptual Model.” The Leadership Quarterly 18 (3): 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002.

- Emmerling, F., C. Peus, and J. Lobbestael. 2023. "The Hot and the Cold in Destructive Leadership: Modeling the Role of Arousal in Explaining Leader Antecedents and Follower Consequences of Abusive Supervision Versus Exploitative Leadership." Organizational Psychology Review 13 (3): 237–278.

- Erickson, A., B. Shaw, J. Murray, and S. Branch. 2015. “Destructive Leadership: Causes, Consequences and Countermeasures.” Organizational Dynamics 44 (4): 266-272.

- Gunaseelan, R. 2016. “Destructive Leadership and Subordinates Intention to Leave: An Empirical Study.” Indian Journal of Research 5 (4): 104–106.

- Hayson, C. M. 2016. “Relationship Between Destructive Leadership Behaviors and Employee Turnover.” Doctoral diss., Walden University.

- Kellerman, B. 2004. Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters? Harvard Business Press.

- Kenton, W. 2023. Durbin Watson Test: What It Is in Statistics, With Examples. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/durbin-watson-statistic.asp

- Kusy, M., and E. Holloway. 2009. Toxic Workplace!: Managing Toxic Personalities and Their Systems of Power. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lipman-Blumen, J. 2005. “Toxic Leadership: When Grand Illusions Masquerade as Noble Visions.” Leader to Leader 2005 (36): 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.125.

- Ministry of Education. 2018. “Ethiopian Education Development Roadmap (2018–30).” https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/ethiopia_education_development_roadmap_2018-2030.pdf.

- Orunbon, N. O. 2020. “Susceptible Followers and Conducive Environment: The Gateway to School Leaders Toxic Behaviour.” Commonwealth Journal of Academic Research. https://www.proquest.com/openview/33b3ddd600ddc250f8967355a88c667c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Owolabi, A. B. 2022. “Destructive Leadership Behavior: How Follower Characteristics Make a Destructive Leader.” Doctoral diss., The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. https://www.proquest.com/openview/33b3ddd600ddc250f8967355a88c667c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Padilla, A., R. Hogan, and R. B. Kaiser. 2007. “The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and Conducive Environments.” The Leadership Quarterly 18 (3): 176–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.001.

- Pelletier, K. L., J. L. Kottke, and B. W. Sirotnik. 2019. “The Toxic Triangle in Academia: A Case Analysis of the Emergence and Manifestation of Toxicity in a Public University.” Leadership 15 (4): 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715018773828.

- Reed, G. E. 2004. “Toxic Leadership.” Military Review 84 (4): 67–71.

- Schaubroeck, J. M., S. T. Hannah, B. J. Avolio, S. W. Kozlowski, R. G. Lord, L. K. Treviño, N. Dimotakis and A. C. Peng. 2012. “Embedding Ethical Leadership Within and Across Organization Levels.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (5): 1053–1078. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0064.

- Schmidt, A. A. 2008. Development and Validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale. University of Maryland, College Park.

- Schneider, C. S. 2021. The Toxic Triangle: A Qualitative Study of Destructive Leadership in Public Higher Education Institutions. Catherine University. Repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/maol_theses/41.

- Sofield, L., and S. W. Salmond. 2003. "Workplace Violence: A Focus on Verbal Abuse and Intent to Leave the Organization." Orthopaedic Nursing 22 (4): 274-283.

- Thoroughgood, C. N. 2013. Follower Susceptibility to Destructive Leaders: Development and Validation of Conformer and Colluder Scales. The Pennsylvania State University.

- Thoroughgood, C. N., B. W. Tate, K. B. Sawyer, and R. Jacobs. 2012. “Bad to the Bone: Empirically Defining and Measuring Destructive Leader Behavior.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 19 (2): 230–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811436327.