ABSTRACT

This study presents findings from an action research project that I completed in my own year 3 classroom. Using the frameworks of praxis (Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.) and sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited by M. Cole et al. Translated by M. Cole. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.), I studied the relationship between praxis-based, decolonised history teaching and year 3 students’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. Student-participants’ work and classroom observations were used as data collection methods. An inductive approach to thematic analysis produced 5 themes, namely: Knowledge of locations across the Roman Empire, People’s physical actions, Characteristics of people that lived in Roman Britain, Migration in the Roman Empire and Students’ disciplinary knowledge.

Introduction

This paper presents findings on an action research project conducted within a primary school classroom. I took on the dual role of teacher/researcher for this study. I taught a sequence of lessons on Roman Britain to my own year 3 students and analysed data collected from those lessons. Data analysis focused on the impact that decolonised history teaching had on a sample of year 3 pupils’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. The research was conducted under the frameworks of praxis (Freire Citation1970) and sociocultural theory (Vygotsky Citation1978).

Praxis encouraged me to reflect on my own teaching and take practical steps to implement social justice in primary history education. Enhancing the year 3 students’ awareness of a heterogenous Roman Britain was an important aspect of the research. I entered this research holding the belief that there is an imbalance of power in curriculum representation, with those from the white, Western world being overrepresented as the agents of the past.

I taught 26 students in a year 3 classroom to gather data for this research. The research was completed in an ethnically diverse school in inner-London. I feel that highlighting a diverse British past is particularly important in diverse areas such as London. It is important that all people feel represented in the historical canon and everybody should see themselves in history.

I took the position that the classroom is a social setting that can develop children’s perceptions. I took on the sociocultural stance that teachers can facilitate and scaffold child development by creating the correct conditions for learning (Vygotsky Citation1978).

I completed this research to demonstrate how teachers can use decolonisation strategies to highlight a heterogenous Roman Britain. This research shows that primary school teachers can diversify their history practice whilst complying with National Curriculum (DfE Citation2013) expectations.

Literature review

How diverse is the primary national curriculum for history?

Writing about history education at secondary level, Mohamud and Whitburn (Citation2016) claim that the school curriculum encourages teachers to focus on the history of the elite, which lacks diverse representation in British history because those from the elite in Britain’s past rarely identified with an ethnic minority background. It is argued that the knowledge presented in school curriculums favours white people and is Eurocentric because it has been designed in the Western world (Apple Citation2019; Moncrieffe Citation2020; Young Citation2016). Apple (Citation2019) and Moncrieffe (Citation2020) both claim schools promote white hegemony through the curriculum. White hegemony ignores the histories of people outside the white world, especially Africa and its diaspora (Mohamud and Whitburn Citation2016).

Apple (Citation2019) posits that hegemony is a form of consciousness that can be both created and recreated in schools. The knowledge presented in the National Curriculum (NC) is the socially legitimate knowledge of society, with the hegemonic values working through educators (Apple Citation2019). According to Apple, however, teachers can challenge these values. By decolonising and diversifying classroom practice, teachers can decentre the dominant, Eurocentric canon on the past (Moncrieffe Citation2020).

How are educators expected to implement the Primary National Curriculum for history?

Ofsted (Citation2021) claims that no content of the NC is innately core and teachers have much freedom to design curricular as they please. The NC is often interpreted merely as a transmission of facts, Cooper (Citation2018) has argued. Lee (Citation2014) contests this claim, however, noting that the more nuanced complexities of history, such as how history is contested and how evidence is used to make claims about the past, have been a part of learning in primary school classrooms since before the 1980s.

It is argued that successful history teaching needs to engage students in investigating significant themes and questions about the past, with people at the centre of class foci (Levstik and Barton Citation2015). According to Ofsted (Citation2021), the subject should bring students into a rich dialogue with the past. They claim children should be learning subject specific history from primary age.

The NC knowledge that students are expected to be exposed to can be defined as substantive or disciplinary. Substantive knowledge includes information on key dates, events and people (Counsell Citation2021). According to Counsell, remembering dates, events, people and the language associated with a topic help pupils navigate that topic with greater ease.

Lee (Citation2014) notes that substantive knowledge is a key goal in history education – however, it cannot be taught alone if pupils are to make sense of historical disagreements. Focusing on substantive knowledge alone tricks pupils into thinking the past is a fixed narrative (Counsell Citation2021). Viewing history as fixed does not give teachers the opportunity to use the classroom to decentre an established, Eurocentric historical canon (Moncrieffe Citation2020).

Teachers should also cover second-order concepts for pupils to question the past. According to Counsell (Citation2021), second-order concepts drive the types of questions historians generally ask. The second-order concepts expected to be taught at key stage 2 are cause, consequence, change and continuity, similarity and difference, historical significance, source and evidence, and historical interpretations (Ofsted Citation2021).

Understanding sources, evidence and interpretations of the past are keyways to understand how people construct history. This is referred to as disciplinary knowledge. According to Ofsted (Citation2021), quality history teaching ensures pupils progress in their disciplinary knowledge. The disciplinary knowledge of history brings sophistication and rational to history lessons, giving pupils the conditions to understand that claims about the past can be both made and contested (Counsell Citation2021). Counsell notes that developing this thought process in pupils is vital if they are to understand history is a construction that can be challenged and questioned. The process of asking questions, finding information and drawing conclusions from historical sources is a form of historical inquiry (Levstik and Barton Citation2015). Levstik and Barton (Citation2015) posit that a good way to take this approach is to build a community of inquiry.

How are people from minority ethnic backgrounds portrayed in history education?

Hall (Citation1997) posits that people from minority ethnic backgrounds are presented in education as irrational, unintelligent and backwards. According to Hall, people of white descent are presented as actors with agency in history, whereas non-white people are presented as objects of the past. These stereotypes can often come through history textbooks and schemes-of-work (Hall Citation1997). The Eurocentric presentation of the past is that human history has been driven by the white race (Young Citation1990).

Young (Citation1990; Citation2016) puts forward his argument on Eurocentrism in history from a postcolonial perspective. According to Young (Citation2016), postcolonialism is a movement that seeks to challenge perceived imperialist systems of economic, political and cultural domination. Postcolonial theory is more concerned with ethnicity and experience than it is with national identity (Clark and Peck Citation2022). Postcolonial critique, Young (Citation2016) posits, is a form of social justice in which the postcolonial theorist puts himself in the position of the oppressed. The oppressed people often face discrimination through the process of ‘otherness’, which Said (Citation1978) defines as a stereotyped, distorted and inaccurate representation of people not of European descent. People from minority backgrounds are presented as intellectually and culturally inferior. This othering, Said posits, occurs through education and can be aimed at people from minority ethnic backgrounds in the West (Said Citation1978).

Stereotyping limits how students from minority ethnic backgrounds see themselves in history. Mohamud and Whitburn (Citation2016) posit that black people in history are often stereotyped by being linked to a history of slavery, African Empires, African American Civil Rights and apartheid. Students seldom learn of people of African descent actively contributing to British history. They note this is also often the case with Muslim students. In her research, Traille (Citation2006) found that black secondary school students and their mothers resent the portrayal of themselves in the past. They can become unengaged with lessons because of the undignified representation that black people face as victims with no agency. These negative experiences can potentially damage pupils’ self-esteem (Mohamud and Whitburn Citation2016). This suggests teachers should be mindful of the ways they represent people from minority ethnic backgrounds in history.

What opportunities does the National Curriculum present for teachers who want to diversify and decolonise their history classroom practice?

In her writing, Ladson-Billings posits that culturally relevant pedagogy develops students academically, nurtures and supports cultural competence and develops critical consciousness (Ladson-Billings Citation1995; Citation2014). Ladson-Billings highlights that culturally relevant pedagogy is successful in the classroom when teachers have expectations for their pupils to achieve academically. Culturally relevant pedagogy accepts attainment targets set in curricular as a measurement of success. This indicates that if primary teachers want to make their practice culturally relevant, they should ensure they still meet NC history attainment targets.

Decolonisation strategies can be used in the classroom to present a heterogenic British past. Focusing on higher education, Behm et al. (Citation2020) note that including more subaltern voices when engaging with sources from the past is a form of decolonisation. To encourage discussions on diversity, multiple perspectives on the past should be shared to expose pupils to differing interpretations of it (Levstik and Barton Citation2015). Exposing pupils to different experiences from the past can make their understanding of history more nuanced, sophisticated, and complex (Moncrieffe Citation2020). Ofsted (Citation2021) expects pupils in primary education to develop their disciplinary knowledge of history by comparing different interpretations of the past.

Moncrieffe (Citation2020) claims decolonisation can be done through transformative critical multicultural education. Primary teachers who want to decolonise their practice, he states, should celebrate cross-cultural encounters in British history and highlight the ethnic and cultural differences of those that contributed to Britain’s past. Traille (Citation2020; Citation2006) argues similarly, claiming the first encounter a child has of his/her ethnicity from the past should be a positive one.

To decolonise, teachers can focus on the people from Britain’s past, rather than British history (Harris Citation2020). If teachers do this, pupils will learn about the range of experiences of the British people in history in all their diversities. Guyver (Citation2021) argues that focusing on the experiences of everyday people that lived in the past does decolonise classroom learning. He suggests this contests and unsettles the traditional canon of the past. It gives teachers the opportunity to present people from different races, ethnicities and cultures as people with agency that have contributed to Britain’s history.

Rather than simply replace one form of knowledge with another, the decolonisation of history suggests teachers facilitate learning that builds on pupils’ disciplinary understanding of the past by exposing them to a wider range of perspectives on it, including perspectives that unsettle the traditional history canon (Moncrieffe Citation2020). This suggests decolonisation can be associated with culturally relevant pedagogy because it aims to both raise cultural awareness and enhance pupils’ academic capabilities and thinking. Decolonisation calls for critical analysis of learning by teachers and students. It encourages disciplinary learning with multiple stories from the past that speak to and against each other (Levstik and Barton Citation2015). Decolonisation ensures this because it encourages the recognition of alternative, subaltern voices. As Mohamud and Whitburn (Citation2016) posit, teachers should not pursue greater diversity in their practice without also seeking to develop the best pedagogy. Ladson-Billings (Citation1995) states that this takes reflection and praxis from teachers.

What are the implications for this Institution Focused Study?

As highlighted in the introduction, I used action research in my own year 3 classroom to diversify and decolonise my practice for this research project. I diversified and decolonised the learning in my classroom whilst teaching the following statutory NC topic:

• The Roman Empire and its impact on Britain. (DfE Citation2013, 190)

I aimed to develop the pupils’ disciplinary knowledge too. I reflected on the evidence for a multicultural Roman Britain that I could share with them. In his book Black and British: A Forgotten History (Olusoga Citation2021), Olusoga highlights the evidence for the presence of African and Asian communities in Roman Britain. Skulls and teeth studied by archaeologists working for the Museum of London indicates the presence of people with Asian and black African ancestry living in Roman Britain (Redfern Citation2018). Records note a presence of foreign fighters from Europe and beyond defending the border of the Roman Empire along Hadrian’s Wall (Segedunum: Tyne and Wear Archives & Museums Citation2023). Levels of mobility have always been known to be high in the Roman Empire and recent archaeological evidence backed up by isotopic and craniometric analysis has supported this claim (Eckardt, Müldner, and Lewis Citation2014).

Evidence shows the presence of Africans and Asians living in Roman Britain as far back as the first century AD. I decolonised my practice for this project by focusing on some of these people. I wanted to see whether this focus would develop pupil-participants’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain.

Methodology

Action research (AR) was used to reflect on curriculum implementation in the classroom. This aligned with my framework of praxis, which Stringer (Citation2014) posits is a form of AR. Throughout the research, I followed the cyclical process of plan, act, observe and reflect (McNiff and Whitehead Citation2010). This made the research design systematic.

Hammersley (Citation2013) notes that qualitative research can be flexible, data-driven and tends to involve the study of a small number of participants within a natural setting. I took on a qualitative approach for this research. I was flexible, changing the research in parts during the action-reflection process. The aim of the research was to collect and analyse the work completed by a sample of participants in my class – therefore, the project was data driven.

I used purposive sampling so that I could choose a sample size that would give me an in-depth analysis of students’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain within the time limitation that I had. I decided to choose a sample of 6 students to focus on. I chose 6 pupils in my class who I predicted would yield enough data to analyse.

Each pupil-participant was given a pseudonym. shows the pseudonym, gender and ethnicity of each pupil-participant. The ethnicities are given according to the school’s database.

Table 1. Pseudonym, gender and ethnicity of each pupil-participant.

The AR that I completed in my classroom involved planning and teaching six key stage 2 history specific lessons. After a first lesson to gain the sample participants’ pre-learning perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain, the remaining 5 lessons used decolonising strategies to develop their understanding of diversity in Roman Britain. Across the lessons, I facilitated various activities that aimed to build on the learners’ perceptions of a heterogenous Roman Britain. The lessons also aimed to develop the pupils’ substantive and disciplinary knowledge, as described in the NC (DfE Citation2013).

Whilst facilitating these lessons, I conducted informal, participant observations taking on a participant-as-observer role (Robson and McCartan Citation2016). Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2018) posit that participant observations are useful to spot things that are not mentioned in other forms of data collection. My observations of the participants’ interactions with the learning enabled me to listen to their verbal descriptions during the lessons. According to Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2018), when an observer remains in a setting over time, he can better identify how events change participants’ perceptions. I completed lesson observations for this research to detect how the participants’ interaction with the learning influenced their perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. By observing the participants’ interaction with the learning over the six lessons, I was able to better infer how the learning changed their thinking.

Robson and McCartan (Citation2016) state that observations are often used as an exploratory phase of research. They state that observations can be used as a precursor to subsequent data collection and analysis. Observations were completed to initially explore the participants’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. Observations of the learning supported my greater focus on collecting and analysing the participants’ written work. Observations were used to triangulate my findings.

The six sample participants’ written work from each lesson was collected and transcribed into a Word document before being uploaded into NVivo. This was so I could complete an in-depth analysis of their writing. Robson and McCartan (Citation2016) note that the purpose of document analysis is to obtain a picture of what might have been missed in an observation. Studying the learners’ written work from the lessons did enable me to analyse their perceptions in greater detail. By analysing the participants’ work, I was able to infer how their interpretations of Romans and Roman Britain had developed over the course of the learning. The analysis of their written work enabled me to infer whether their changing perceptions correlated according to their interaction with the classroom learning.

I used NVivo to complete a thematic analysis (TA) of the written work completed by the six participants. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) describe TA as a method used in research to identify, analyse and report patterns. Gibbs (Citation2018) notes that a systematic approach to TA can be used to index and categorise the data that you have collected. I used TA to analyse the data that I collected for this project so I could identify themes to report on. Taking the systematic approach suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) helped me index and categorise the large amount of written data that I had acquired.

Gibbs (Citation2018) argues that when taking a systematic approach to TA, the researcher can pay close attention to what the respondents say. This, he argues, enables the researcher to discover participants’ actual experiences, which can challenge the researcher’s own theoretical presuppositions. Coding the participants’ writing sentence-by-sentence did enable me to analyse their experiences of the learning in detail. It gave me the opportunity to take a focused look at their perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. This encouraged me to take an inductive approach, with themes emerging during the analysis process (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Ethical approval for this research was gained from UCL Institute of Education. I followed the BERA (Citation2018) ethical guidelines for research in education. The Headteacher of the school read an outline of the research before signing a consent form. I also prepared an outline of the research for the students in my class and their primary caregivers. Primary caregivers read the outline and were given the option to opt their child out of the research. I read an outline of the research with the students in my class and they were given the option to opt into it.

Findings

The findings have been structured into the 5 defined themes given in the abstract. As mentioned, these themes were identified by taking an inductive approach to analysis.

Theme 1:knowledge of locations across the Roman Empire

In Lesson 1, the participants were asked a sequence of questions to give their perceptions of Romans that they saw in history textbooks. The following question was used to elicit their perceptions on where they thought the Romans in the books came from before the praxis-based, decolonising learning occurred.

- Where do you think the Romans in the books come from?

Ayo, Ime, Jasper and Leo all stated that they thought the Romans in the books came from Italy in Lesson 1. Omolara stated that they came from Rome. Umar did not answer the question.

It might be argued that Ayo, Ime, Jasper, Leo and Omolara gave these statements in Lesson 1 because of the white Eurocentric nature of the textbooks. This data might also indicate that Lesson 1 reinforced their white hegemonic understanding of history, which Moncrieffe (Citation2020) and Apple (Citation2019) claim saturates education.

As the lessons progressed, the learners developed an understanding that the Roman Empire was expansive and that Roman citizens came from across it – including from Africa and Asia. The data shows multiple references to provinces and locations across the Empire in the participants’ writing. The provinces and locations referenced did correlate with those that the students learned in the lessons.

The praxis-based, decolonised learning did try to enhance the students’ understanding that Romans did not just come from Italy and Europe. From Lesson 2 onwards, there were references in the data to racial and ethnic diversity across the Roman provinces and in Roman Britain. For example, there were references to Romans being ‘mixed-race’ and having ‘African characteristics’. However, there is not enough evidence to suggest the learners understood wider cultural diversity across the provinces. Although racial and ethnic diversity across the Empire was highlighted in the teaching, the limited time available meant that other aspects of cultural diversity across the provinces – such as different languages spoken, clothes worn, religions celebrated and food eaten – were not explored. It seems reasonable to suggest, then, that there could have been a greater focus on cultural diversity to further decolonise the learning.

The learners cited locations both within and beyond Europe in their writing. Specific locations were often mentioned in the same lesson that the participants learned about them. For example, Ime stated in her writing that ‘skeletons of African Romans have been found in York’ after learning about Ivory Bangle Lady. Morocco, Algeria and Iraq were referenced in Lesson 3, which highlighted that some of the garrisons stationed along Hadrian’s Wall came from those locations. This gives me reason to suggest the interaction with the learning did influence the participants’ writing. Their writing suggests the learning helped them notice that Roman citizens (including soldiers) living in Britain came from beyond Europe.

Theme 2: people’s physical actions

References to physical actions did include some general actions such as building and trading. However, the pupils’ written descriptions of physical actions generally related to fighting for and defending the Roman Empire. The learning developed the participants’ understanding that soldiers from across the Empire fought for it.

There were multiple references in the data to people fighting for the Roman Empire. A reading of the data might indicate there were multiple references to fighting because much of the learning did focus on Roman soldiers, particularly at Hadrian’s Wall. This could reflect my own perception on Roman history as a period of fighting and conquest, which could be considered a limitation of my own teaching.

There was variation between the participants’ references to fighting. References to fighting for the Empire were coded 11 times for both Jasper and Umar, the most of all the participants. References to fighting were coded 5 times for Ime, the least of all the participants. There is reason to argue, therefore, that the learning influenced the participants’ writing in different ways. Sociocultural theory does note that child development can be periodic and uneven, with social interactions in the classroom leading to different cognitive development according to the pupil (Vygotsky Citation1978).

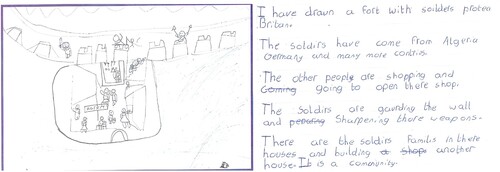

For Lesson 3, pupils had to locate the modern-day birthplaces of garrisons that were stationed along Hadrian’s Wall. The learners were asked to draw and describe their own setting along Hadrian’s Wall after this activity. shows some of the sentences they used in their descriptions. The table shows that Ayo and Leo both used the word ‘protecting’ in their sentences. Jasper, Omolara and Umar all used ‘defending’ in their writing. The use of these terms implies they were aware that the garrisons stationed along Hadrian’s Wall were there to defend/protect Britain.

Table 2. Some of the participants’ written work from Lesson 3 describing an image of Hadrian’s Wall that they drew.

The participants were also asked to note where the soldiers in their images had come from. They noted that the soldiers came from the following modern-day locations:

Ayo: Algeria, Germany and ‘many more countries.’

Ime: Spain and Iraq.

Jasper: Morocco.

Leo: Spain.

Omolara: Iraq, Hungary and Switzerland.

Umar: Spain.

A focus on the active contribution to Britain’s past by people from minority ethnic backgrounds is often lacking in the retelling of British history (Hall Citation1997; Mohamud and Whitburn Citation2016; Traille Citation2020). As mentioned, the learning aimed to develop the participants’ perceptions of racial and ethnic diversity amongst the soldiers at Hadrian’s Wall. I wanted the learners to understand that people from minority ethnic backgrounds actively contributed to Roman British history.

My observation of the lessons was that the participants understood that soldiers stationed at Hadrian’s Wall were not only white. I wanted this knowledge of soldier diversity to be reflected in their images from Lesson 3. However, none of the learners cited race or ethnicity when describing their soldiers. I reflected that this might have been because none of the questions in Lesson 3 encouraged this. The participants’ work from Lesson 3, however, does show that Ayo, Ime, Jasper and Omolara created a setting with non-European Roman soldiers actively defending Britain.

Theme 3: characteristics of people that lived in Roman Britain.

Some of the learning focused on the identities of the people that lived in Roman Britain. This encouraged the pupils to describe people’s physical characteristics in their writing. References to race and ethnicity, gender and social class were made across the lessons. There did seem to be correlation between the facilitated learning and participants’ written descriptions of Roman people’s physical characteristics. For example, questions in Lesson 1 asked the learners to describe what the men and women in textbooks about the Romans looked like. There were 13 references to gender in that lesson. Similarly, part of Lesson 3 focused on the race and ethnicity of the Aurelian Moors. The data showed 9 references to race and ethnicity in that lesson. There is reason to argue, therefore, that the pupils’ interaction with the learning encouraged them to cite physical characteristics in their writing.

There were multiple references to race and ethnicity across the learning. For example, Omolara wrote that the Aurelian Moors were an ‘African community in Britain’ in Lesson 2. Umar wrote that the word ‘moors’ means ‘people from North Africa’ in Lesson 3. Ime wrote that Roman Britain had ‘different races and cultures’ in Lesson 6. It might be suggested there were multiple references to race or ethnicity because decolonised learning does aim to highlight racial and ethnic diversity (Behm et al. Citation2020; Moncrieffe Citation2020).

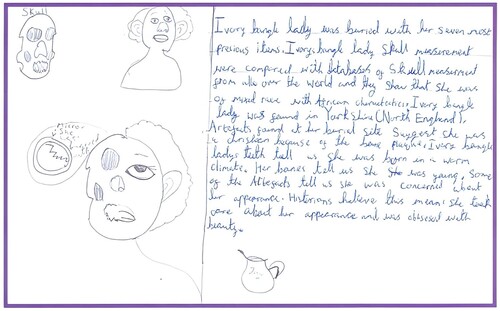

Lesson 4 focused on the race, ethnicity, gender and social status of Ivory Bangle Lady. After researching Ivory Bangle Lady, participants completed a museum information plaque to describe her. Across their writing for this activity, Ivory Bangle Lady’s race was cited more than other forms of her identity.

gives some of the sentences used in Lesson 4 to describe Ivory Bangle Lady. The table shows that Ivory Bangle Lady’s race was described by Ayo, Jasper, Leo and Omolara. Their writing indicates they noticed that people from different races lived in Roman Britain. Omolara also noticed that Ivory Bangle Lady had ‘African characteristics’ in her sentence. There is reason to argue that highlighting Ivory Bangle Lady’s race developed the participants’ perceptions of diversity in Roman British history.

Table 3. References to Ivory Bangle Lady’s race from Lesson 4. The participants completed a museum information plaque to describe her.

Theme 4: migration in the roman empire.

In Lesson 2, the pupils learned that Roman citizens were able to move freely around the Empire. At the end of this lesson, the learners were asked to complete an exit card explaining something new they had learned. shows what some of the pupils wrote on their exit cards. The table shows that Ime and Jasper used the word ‘moved’ in their sentences. Leo and Umar used the word ‘travelled’ in their sentences. The use of these words shows that these participants noticed that movement around the Empire occurred. They noticed that Roman citizens travelled ‘freely’ (Leo) and ‘whenever they wanted’ (Ime).

Table 4. Sentences that some of the participants wrote on their exit cards at the end of Lesson 2 to explain something new they had learned.

In Lesson 3, furthermore, pupils were asked to draw and describe their own setting along Hadrian’s Wall. shows Ayo’s image and description from that lesson.

The writing and image in show that Ayo included soldiers and their families from Algeria, Germany and ‘many more countries’ in her image. She described her setting as a ‘community’ in her final sentence. It might be suggested that by including people that migrated from Algeria and Germany in her image, Ayo drew a setting with a multi-ethnic community. However, there is not enough information in her writing to confirm this. Although she mentioned where the soldiers and their families came from, Ayo did not specifically describe anybody’s race or ethnicity.

shows that Jasper and Omolara also mentioned where the people in their images came from, but did not cite anybody’s race or ethnicity. The table shows that like Ayo, neither Jasper nor Omolara gave detail on the identities of the people in their images beyond where they had migrated from. This makes their writing basic and limits my interpretation of their perceptions.

Table 5. Jasper and Omolara’s written descriptions of images they drew of garrison posts stationed along Hadrian’s Wall.

However, and show that Ayo, Jasper and Omolara each created an image with people that migrated to Roman Britain from outside Europe to build communities. This reflects a different perception to what these participants held in Lesson 1. In Lesson 1, they wrote that Romans migrated to Britain from either Italy (Ayo and Jasper) or Rome (Omolara).

Another lesson that developed an understanding of migration to Britain from beyond Europe was Lesson 4, which focused on Ivory Bangle Lady. For this lesson, pupils were asked to navigate a website named Romans Revealed (University of Reading and Runnymede Trust Citation2023). After using the website to research Ivory Bangle Lady, pupils designed their own museum information plaques to describe her.

is the museum information plaque written by Omolara. The writing in suggests Omolara associated migration with Ivory Bangle Lady. She knew her body was found in Yorkshire. She was aware that she was mixed-race with African characteristics. She noted that Ivory Bangle Lady’s teeth ‘tell us’ she was born in a warm climate. The figure indicates Omolara knew Ivory Bangle Lady’s presence in Britain was a consequence of migration.

The other participants also referenced Ivory Bangle Lady’s race, ethnicity and social status in their museum information plaques. Ayo wrote that Ivory Bangle Lady ‘came from North Africa’. She identified her as ‘mixed-race’ and wrote that she ‘lived in a rich family’. Jasper and Ime also noted that Ivory Bangle Lady was mixed-race and rich in their museum information plaques. This suggests that their interaction with the learning helped them notice that wealthy people migrated to Roman Britain from beyond the white world. This is not the ‘othering’ and stereotyping of people from minority ethnic backgrounds that Said (Citation1978), Mohamud and Whitburn (Citation2016) and Traille (Citation2020) claim children in education are often exposed to in history lessons. There is reason to argue that in their museum information plaques, these participants reflected the positive representation of African migration that Traille (Citation2020) posits pupils should experience at an early age. These descriptions do unsettle the traditional history canon.

Theme 5: students’ disciplinary knowledge.

The learning included slides that highlighted the authors of the historical sources that were being studied. The intention of these slides was to try to enhance the pupils’ understanding that accounts of the past have authors. I felt this was a good way to introduce the year 3 pupils to historical construction at the beginning of key stage 2.

The students were encouraged to cite evidence when making claims about diversity in Roman Britain. There is evidence in some of the data to suggest this had an impact on their writing. For example, Ayo wrote that archaeologists think Ivory Bangle Lady came from North Africa ‘because of her skull’, and Jasper wrote that there is evidence the Aurelian Moors were stationed in Aballava because it was ‘written in one text and has been written in stone’.

All participants mentioned bones, teeth, artefacts and written sources as evidence to support their claims that Roman Britain was diverse. Some of them were more specific when citing written sources of evidence in their writing. For example, Ime and Omolara both specifically named Notitia Dignitatum as a primary source of evidence that detailed the first recorded African community in Britain.

In Lesson 4, discussions in pairs, on tables and across the classroom focused on how bones and artefacts give clues to Ivory Bangle Lady’s identity. In their writing, participants referenced Ivory Bangle Lady’s bones when citing her race and ethnicity. Ime, Jasper, Leo and Omolara all wrote that her skull suggests she was mixed-race. Ayo wrote that her skull suggests she was African. This writing reflects an awareness that archaeological evidence gives clues to racial diversity in Roman Britain.

Teacher-student and student-student interaction is a key feature of sociocultural theory. Talking was encouraged in some of the activities so learners could listen to and question differing perspectives on Roman history. In Lesson 6, for example, the pupils revisited and discussed textbooks that they looked at in Lesson 1. As a class, we focused on and discussed the information in the one of the books. We discussed how the perspectives we focused on during lessons 2, 3, 4 and 5 differed from the information in the book.

After this whole class discussion, the pupils wrote a letter to the publishers of the book suggesting how they might improve their text next time they write it. All participants took a critical perspective on the publisher. For example, Omolara wrote that she would like to see more evidence about migration and diversity in Roman Britain. Ime noted in her letter that David Olusoga and Dr Hella Eckardt focus on migration in Roman Britain. She told the publisher that their next book should do the same. Umar took a critical stance by telling the publisher that he did not see any Romans from Iraq and Syria in their book. This suggests he thought the book should go beyond the Eurocentric representation that was evident. Ayo wrote that the book should include information on where the people in the text came from so readers can know if they looked the same or different to them. Jasper suggested the book should highlight that Romans had different races and cultures. Finally, Leo wrote that it is important to learn about Ivory Bangle Lady to look at evidence of migration and diversity. In their writing for this activity, all the participants questioned and challenged the representations of Romans and Roman Britain that they saw in the book.

Discussion

Going into the learning, I took the stance that all the participants would have the Eurocentric, white hegemonic mindset of Roman British history described by Moncrieffe (Citation2020) and Apple (Citation2019). There is evidence in some of the data items to support this. In Lesson 1, none of the participants acknowledged that Romans living in Britain could have come from an ethnic minority background. Five of the participants wrote that Romans came from either Italy or Rome in the lesson. The participants’ written work from this lesson shows no awareness of the heterogenous Roman Britain described by Olusoga (Citation2021) and Eckardt, Müldner, and Lewis (Citation2014).

My praxis stance encouraged me to act within my own classroom to challenge this white Eurocentric perception of Roman Britain that was reflected in Lesson 1. Highlighting the contribution to British history made by people from outside the white European world is something that Moncrieffe (Citation2020) encourages to decolonise learning. This is something that I did. There is evidence in the data to suggest this developed the participants’ perceptions of the people that lived in Roman Britain. For example, the data shows an awareness that people from beyond Europe migrated to, defended and built communities in Roman Britain. There are references to ‘skeletons of African Romans’ being found in York, the first African community in Britain and ‘mixed-race’ Romans living in Roman Britain. Comparing this to written work from Lesson 1 does indicate that the participants’ perceptions of Roman Britain’s population developed in correlation with the learning. However, there is no evidence in the findings to suggest this has affected the participants’ wider thinking on a diverse, heterogenic British past. Further action research is needed.

This report does not claim to have proven a causal link between classroom learning and participants’ perceptions of Romans and Roman Britain. However, there is correlation between perceptions reflected in the participants’ written work and the focus of the learning. For example, their writing shows that they started to notice citizens could move freely across the Empire in Lesson 2. This lesson focused on free movement across the Empire and how this led to more migration to Roman Britain. Lesson 4 focused on the identity of Ivory Bangle Lady. The participants’ writing described her as ‘mixed-race’, having ‘African characteristics’, being from ‘North Africa’ and coming from a ‘hot climate’ in this lesson. References to Roman people’s characteristics occurred in correlation with the learning.

Some of the data items suggest participants in this study did understand that migration to Britain was commonplace in the Roman era. There is some evidence in all the participants’ written work to indicate a perception of Roman British history beyond the white, Eurocentric canon that Moncrieffe (Citation2020) and Young (Citation2016) claim is commonplace in education. This perception was developed with the participants learning about the lives of people that had migrated to Roman Britain from Africa, Asia and mainland Europe. There is reason to argue that the learning developed their understanding that Roman Britain was influenced by the ‘wider world’ – namely, the Roman Empire.

The NC suggests key stage 2 students should understand how knowledge of the past is constructed (DfE Citation2013). I do not suggest any of the participants met this target. However, I do note that this is an end of key stage 2 target and the students for this research were in year 3 at the time of the learning. The lessons developed all participants’ understanding that historical sources have authors. There were times in the lessons when the participants cited sources when making claims about diversity in Roman Britain.

The NC (DfE Citation2013) states that students in key stage 2 should regularly address second-order concept thinking. There is reason to argue that the learning developed an understanding of similarities and differences between the people that lived in Roman Britain. For example, all participants showed an awareness that the soldiers stationed along Hadrian’s Wall came from different locations across the Empire. Their writing also showed that they noticed racial and ethnic diversity in Roman Britain. It might also be argued that their written work showed some understanding of the causes and consequences of migration to Roman Britain. For example, some of the participants expressed an awareness of migration across the Empire in their writing. There is also evidence in some of the data to suggest an awareness that migration to Roman Britain led to diverse communities.

Lee (Citation2014) states that although children as young as seven can understand second-order concept thinking, it is hard to measure their ability to do this just by looking at their work. From the data, it is difficult for me to interpret a wider comprehension of second-order concept thinking in the participants. I cannot comment on whether they will be able to transfer second-order thinking skills to other history topics. A wider, whole-school action research study would be needed for this.

Limitations and concluding comments

I am aware that this was a study conducted in a single classroom setting. The sample size of six pupil-participants limits claims I can make on the effectiveness of the learning. The data that I analysed was written work completed by the participants across six lessons. I am unsure whether any of them have retained perceptions of a heterogenous Roman Britain because I have not been able to follow up on the findings. I do not know if these findings suggest any wider perceptions of diversity in British history. All participants are now in a new year group with a different teacher. The findings presented are my own interpretation of a limited number of participants’ interpretations of a particular period from British history.

From a subjective standpoint, I accept that bias is likely to exist in my own interpretation of the data. Stenhouse (Citation1975) suggests practitioner research such as this should sit as an example for other practitioner researchers to try and test. I suggest other teachers conduct insider research into decolonising primary history education to challenge or verify my findings.

I failed to gain as much data from the participants as I wanted. I do reflect that the dual role of teacher/researcher was more challenging than I anticipated. I have reflected that my questioning in some of the lessons did not encourage the pupils to express their understanding of cultural diversity in Roman Britain as I would have wanted. A greater focus on questions for the pupils to answer will take place next time I conduct similar insider research.

I have reflected on my own positionality on history and how this might have impacted the learning that occurred. As a white-British male, I am aware that I am not a marginalised minority, which does impact my understanding of discrimination and marginalisation. I used praxis to reflect on this and attempt to understand marginalisation in the curriculum, as suggested by Freire (Citation1970) and Darder (Citation2015).

This research has taught me that it is possible to deliver the NC whilst also challenging the underrepresentation of people from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds in Roman history. With a praxis mindset, I demonstrated that subaltern voices can be included in the retelling of Roman Britain. I suggest that through reflection and with a praxis mentality for social justice, other teachers can do the same when teaching other topics from the primary history curriculum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Apple, M. 2019. Ideology and Curriculum. 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

- Behm, A., C. Fryar, E. Hunter, E. Leake, S. L. Lewis, and S. Miller. 2020. “Decolonizing History: Enquiry and Practice.” History Workshop Journal 89 (1): 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbz052.

- BERA. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, Fourth Edition. 4th edn. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Clark, A., and C. L. Peck. 2022. “Introduction: Historical Consciousness: Theory and Practice.” In Contemplating Historical Consciousness: Notes from the Field, edited by A. Clark and C. L. Peck, 1–16. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education. 8th edn. New York: Routledge.

- Cooper, H. 2018. “Children, Their World, Their History Education: The Implications of the Cambridge Review for Primary History.” Education 3-13 46 (6): 615–619.

- Counsell, C. 2021. “History.” In What Should I Teach? Disciplines, Subjects and The Pursuit of Truth, edited by A. S. Cuthbert and A. Standish, 2nd edn, 154–173. London: UCL Press.

- Darder, A. 2015. Freire and Education. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Department for Education. 2013. The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document. Crown Copyright. Accessed July 1, 2023.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf.

- Eckardt, H., G. Müldner, and M. Lewis. 2014. “People on the Move in Roman Britain.” World Archaeology 46 (4): 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.931821.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

- Gibbs, G. 2018. Analyzing Qualitative Data. 2nd edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Guyver, R. 2021. “Doing Justice to Their History: London’s BAME Students and Their Teachers Reflecting on Decolonising.” Historical Encounters 8 (2): 156–174.

- Hall, S. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

- Hammersley, M. 2013. What is Qualitative Research. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Harris, R. 2020. “Decolonising the history curriculum.” BERA Research Intelligence: Decolonising the Curriculum Transnational Perspectives (142 Spring 2020), pp. 16–17.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 1995. “But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” Theory Into Practice 34 (3): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 2014. “Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: A.K.A The Remix.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (1): 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751.

- Lee, P. 2014. “Fused Horizons? UK Research into Students’ Second-Order Ideas in History: A Perspective from London.” In Researching History Education: International Perspectives and Disciplinary Traditions, edited by M. Koster, H. Thunemann, and M. Zulsdorf-Kersting, 170–194. Frankfurt: Wochenschau Verlag.

- Levstik, L., and K. Barton. 2015. Doing History Investigating with Children in Elementary and Middle Schools. New York: Taylor and Francis (5).

- McNiff, J., and J. Whitehead. 2010. You and Your Action Research Project. 3rd edn. London: Routledge.

- Mohamud, A., and R. Whitburn. 2016. Doing Justice to History: Transforming Black History in Secondary Schools. London: Trentham Books.

- Moncrieffe, M. L. 2020. Decolonising the History Curriculum. Euro-Centrism and Primary Schooling. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Imprint: Palgrave Pivo.

- The Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills. 2021. “Research Review Series: History. Crown Copyright.” Accessed July 1, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-review-series-history/research-review-series-history.

- Olusoga, D. 2021. Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Picador.

- Redfern, R. 2018. The Surprising Diversity of Roman London, Museum of London Docklands. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/surprising-diversity-roman-london-docklands.

- Robson, C., and K. McCartan. 2016. Real World Research. 4th edn. New York: Wiley.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Random House Inc.

- Segedunum: Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums. 2023. Where did the Soldiers Living along Hadrian’s Wall come from? Accessed September 1, 2023. https://segedunumromanfort.org.uk/learning/where-did-the-soldiers-living-along-hadrian-s-wall-come-from.

- Stenhouse, L. 1975. An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. London: Heinemann.

- Stringer, E. 2014. Action Research. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Traille, K. 2006. School History and Perspectives on the Past: A Study of Students of African Caribbean Descent and their Mothers. Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Institute of Education, University of London.

- Traille, K. 2020. Teaching History to Black Students in the United Kingdom. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- University of Reading and Runnymede Trust. 2023. Romans Revealed. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.romansrevealed.com/.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited by M. Cole et al. Translated by M. Cole. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Young, M. 1990. White Mythologies: Writing History and the West.

- Young, R. 2016. Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction Anniversary Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.