ABSTRACT

The Swedish preschool curriculum places strong emphasis on the home – preschool partnership and parent engagement in this regard is considered important for reasons such as promoting child well-being and a healthy development. The central target of inquiry of this study was thus to explores the three primary perspectives that interconnect in the preschool – home partnership (child, parent, teacher) and applies this exploration in order to better understand what parent engagement in preschool means to the child. Central to the study was determining the child’s position within the partnership, thus the theoretical framework of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory was applied. Stories were collected through interviews which highlighted the interconnectedness of the three perspectives and analysed using story constellations. Through identifying harmonies and contradictions in the stories, the construct of children’s, parents and preschool teachers understanding of parent engagement in the Swedish preschool has been investigated, shedding light on the child’s sense of agency within the partnership.

Introduction

During the 1960s, the Swedish state took some important initiatives in early childhood education and care (hereafter referred to as ECEC) and soon the preschool system became a significant pillar in the mechanism for ensuring that women joined the working forces. Hence, its role in Swedish family policy was established (Hartman, Citation2005; Population Europé Resource Finder and Archive [PERFAR], Citation2008; Swedish Agency for Education, Citation2010; Tunberger & Sigle-Rushton, Citation2011). Today the vast majority of all Swedish children, regardless of socio-economic status, attend preschool (Hartman, Citation2005) and affordable childcare has become every family’s right. According to Hayes, O’Toole, and Halpenny (Citation2017) there is an increasing focus on the role of parents in children’s ECEC and the significance parent engagement in preschool may have on children’s development. International educational research highlights ‘the importance of understanding children’s learning as embedded in the social, cultural and family contexts in which it occurs’ (Alanen, Brooker, & Mayall, Citation2015, as cited in O’Toole, Citation2017) and the overall consensus is that children will, in a well-being, development and learning perspective, do better with parents who are actively engaged in their pedagogical development (Borgonovi & Montt, Citation2012; Emerson, Fear, Fox, & Sanders, Citation2012; Goodall & Vorhaus, Citation2011). Thus, designing pathways in order to develop the communication between home and preschool is considered a significant factor in children’s developmental outcomes (Hayes et al., Citation2017).

This study rests against the theoretical framework of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. The theory defines six layers of environment, each which are considered imperative in understanding the wholeness of a child’s development. The first and perhaps most important of Bronfenbrenner’s definitions, is that,

the ecology of human development involves the scientific study of the progressive, mutual accommodation between an active growing human being and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which the developing person lives, as this process is affected by relations between these settings, and by the larger contexts in which the settings are embedded. (Citation1979, p. 21)

teachers are responsible for,

each child, together with their parents, receiving a good introduction to the preschool,

for ensuring that parents receive opportunities to participate and exercise influence over how goals can be made concrete in pedagogical planning,

for the content of the development dialogue, its structure and how it is carried out, and

for involving guardians in assessing the work of the preschool (Swedish Agency for Education, Citation2010).

The work team should,

show respect for parents and be responsible for developing good relationships between staff of the preschool and the children’s families,

maintaining an on-going dialogue with guardians on the child’s well-being, development and learning, both inside and outside the preschool, and holding annual development talks and,

take due account of parents’ viewpoints when planning and carrying out activities (Swedish Agency for Education, Citation2010).

This division of responsibilities suggests that a mutual engagement between the preschool and the home is central in the welfare state’s task to provide Swedish children with the necessary prerequisites to maintain well-being and a healthy development within the sphere of ECEC.

Literature review

International context

Existing international literature highlights significant correlations between parent engagement and children’s mental health and well-being (Gilleece, Citation2015; Hornby & Lafaele, Citation2011) emphasizing the importance of understanding children’s learning as embedded in the family, social and cultural contexts in which it occurs (Alanen et al., Citation2015). However, whilst this has led to an increased focus on the parents’ role in children’s learning within the global debate (Hayes et al., Citation2017) it has not illuminated the child’s voice in the debate. With heavy emphasis on children’s performance and how parent-participation in matters such as homework, teacher–parent evenings and so on, affect children’s learning development, recent international research is limited to parents being actively involved in the actual academic education of the child (Borgonovi & Montt, Citation2012; Emerson et al., Citation2012; Goodall & Vorhaus, Citation2011), overlooking perhaps the less dogmatic values such as children’s understanding and meaning-making. Against this background, research on children’s perspective in terms of parent engagement, can be divided into two categories. The first category identifies research concerned with cognitive outcomes, considering primarily the

critical factors affecting children’s educational outcomes across the world which include families socio-economic and cultural status (Harju-Luukkainen et al., Citation2018; Yamamoto & Holloway, Citation2010), parental involvement in their child’s education (Christenson, Citation2004; Fantuzzo, Tighe, & Childs, Citation2000) and the type of expectations that families have (Siraj-Blatchford, Citation2010). (As cited in Uusimäki, Yngvesson, Garvis, & Harju-Luukkainen, Citation2019)

Swedish context

An increased interest surrounding the subject of parental engagement in preschool in a Swedish context has emerged in recent years and an overall heavy emphasis on establishing strong teacher-parent relationships in the Swedish National Curriculum for Preschools and parental engagement in preschool have been highlighted as important for reasons such as promoting a healthy development of the child, as well as socialization and learning through play (Johansson & Pramling Samuelsson, Citation2006; Löfdahl & Hägglund, Citation2006; Widding & Berge, Citation2014). However, little or no emphasis is placed on the child’s perspective within the academic debate. When compared to other nations, parents in Sweden share the task of childcare with professional early years educators in preschool, which means that this relationship between home and preschool is of great significance for the child’s healthy cognitive development and self-concept (Chong & Liem, Citation2014; Nisbett et al., Citation2012; Phillipson & Phillipson, Citation2012, Citation2017). Swedish children are thus subject to the supervision-, care- and education of both parents and teachers in two different settings, that of the home and that of the preschool, making collaboration between the micro-systems of preschool- and home all the more significant. According to the OECD there is an increasing global interest concerning the area of parental engagement in ECEC (OECD, Citation2012/Citation2015/Citation2017) existing research primarily represents the teacher’s voice (Hakyemez-Paul, Pihlaja, & Silvennoinen Citation2018; Hujala, Turja, Gaspar, Veisson, & Waniganayake, Citation2009; Venninen & Purola, Citation2013) leaving it overrepresented in comparison to the child’s voice. Hence, the domain between home and preschool in Sweden today is one that is widely discussed in the academic debate and, although many studies have shown that positive cooperation between the child’s ECEC microenvironments, have been of great benefit to the child’s learning and development (Patel & Corter, Citation2012; Persson & Tallberg Broman, Citation2017; Markström & Simonsson, Citation2017; Murray, McFarland-Piazza, & Harrison, Citation2014; Vlasov & Hujala, Citation2017), very few of these include the child’s perspective.

The Nordic tradition of inclusion have resulted in several research projects where parental engagement has been focal and by comparison, Finland initiated the International Parent- Professional Partnership (IPP) research study, which was conducted by Hujala et al. (Citation2009). The study explored the teacher-parent collaborations in ECEC services in five countries (Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Norway and Portugal) and emphasis was placed on the teachers’ views of parents’ involvement in preschools. The study found that parents differed in their capacity to establish and maintain relationships with teachers. In another study conducted by Hakyemez-Paul et al. (Citation2018), with a sample of 287 educators (with both qualitative and quantitative data), it was identified that the Finnish preschool teachers generally possess a positive attitude towards parental engagement and that a participants found the difficulties of parental engagement to oftentimes be caused by poor motivation on the parents behalf, as well as lack of time on both parents’ and preschools part. From an ecological perspective, it is vital to examine linkages among central settings in a child’s life. Parent’s involvement in children’s education both at school and at home promotes the role of the parent in the Swedish preschool curriculum and embodies the idea that Swedish society has a comprehensive view of the child, meaning we talk about ‘the whole child’. ‘The whole child’, refers to all aspects of the child, which in a preschool perspective, means that the child’s entire day is carefully planned for, including meals, toilet needs, sleep, play and learning through play (Swedish Agency for Education, Citation2010). These areas of the child’s pedagogical day must also represent the parents needs in regard to their child, on a holistic as well as practical level (Markström & Simonsson, Citation2017). These distal systems that forms part of a child’s life, have been investigated to some extent; including analysis and comparative studies of steering documents and policies where documentation of the child’s pedagogical day is focal (Emilson & Pramling Samuelsson, Citation2014; Harju-Luukkainen et al., Citation2018; Löfdahl, Citation2014; Löfgren, Citation2015; Sheridan, Williams, & Sandberg, Citation2013). However, in order to determine the associations between levels of parental preschool engagement and child outcomes on an institutional level, the child’s narrative must be included alongside the policy narrative (Tan & Goldberg, Citation2009) promoting a search beyond the individual child and into the child’s nested environments instead.

Policy makers as well as researchers normally view and present engagement between home and educational institutions in a positive light and some researchers have devoted their time to researching parents many roles in relation to educational institutions (Crozier, Citation2000; Hanafin & Lynch, Citation2002; Markström & Simonsson, Citation2017). However, critical research has posed the question of whether or not this engagement is in fact beneficial for all parties (Crozier, Citation2000; Markström, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Osgood, Citation2012; Vincent & Ball, Citation2006). For instance, the large inequalities in both socio-economic and ethnic background are viewed as troublesome in an engagement perspective – largely due to differences in belief-systems and personal culture (Bæck, Citation2010; Bouakaz & Persson, Citation2007; Englund, Citation2010). Thus, as mentioned earlier, on a political and social level, the three primary discourses that have been identified remains the same: responsibility, performativity and efficiency (Markström & Simonsson, Citation2017), all three pertaining largely to the preschool and its staff, again leaving (it) devoid of the child’s perspective.

Purpose of study

There is an overall heavy emphasis on establishing strong teacher-parent relationships in the Swedish National Curriculum for Preschools and as we have seen thus far, parent engagement in preschool is considered important for reasons such as promoting child well-being and development, as well as socialization and learning through play (Johansson & Pramling Samuelsson, Citation2006; Löfdahl & Hägglund, Citation2006; Widding & Berge, Citation2014). As well as being asserted by the UN Convention of The Rights of the Child, the ambition of a healthy development of the child is further supported by the Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory, where the ecological development ‘is conceived as a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like Russian dolls’ (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, p. 3) and that ‘the innermost level is the immediate setting containing the developing person’ (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, p. 3). Against this background, the central target of inquiry of this study was thus to explores the three primary perspectives that interconnect in the preschool – home partnership (child, parent, teacher) and applies this exploration in order to better understand what parent engagement in preschool means to the child.

Method

The empirical material was generated in four sets of data (a) interviews with children in the preschool (1) and the home environment (2), (b) interviews with parent, (c) interviews with preschool teachers. The children who participated in the study were all boys: Noah, 4.5 years old, Elliot, 5 years old and Mason, also 5 years old. The data were collected through interviews and observations were done in triads of child–parent–teacher. The narratives collected from all nine participants were compiled then demonstrated and analysed in story constellations. During the in total six children’s interviews, whereof each child partook in three interviews each, two in the preschool setting and one in the home setting, careful consideration was placed on observations of the child’s positioning within their stories. Obtaining data that provided insights into how the participants viewed the preschools role in the children’s and their own lives in relation to the rest of the world (Bryman, Citation2016), was poignant. For this reason, a semi-structured interview that would allow freedom to move within the paradigms of each question was determined upon. A series of three separate interviews with each participating child was executed. The interviews with the parents and teachers were two-pronged: first a 60-minute face-to-face interview, then a follow-up interview by telephone.

The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations. The study comprises of three children, three mothers and three teachers from whom narratives have been collected and placed in relation to one another. The study therefore is in its very essence limited to nine voices. The study was executed in accordance with the ethical requirements of the United Nations and the Swedish Research Council. Furthermore, the matter of consent versus assent when researching with children was considered throughout the study.

Findings

As we will see below, the study had three major findings. These were the discrepancies between the participants understanding, meaning and practice of parent engagement as stipulated in the curriculum. The stories of the nine participants were investigated and harmonies and discrepancies between the children’s and the adult’s understanding were identified.

Finding 1: understanding

When discussing the cognitive development perspective of children and how the interactions of the participants of the children’s lives affect a child’s development, we note that according to Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) the more encouraging and nurturing these relationships and places are, the better the child will be able to develop healthily. The mother in Case 1 claimed absolute trust in the system and volunteered that she had never read the curriculum, engaged in the preschool beyond the daily dialogues at drop-off and pick up, or ever consciously attempted to deliberately extend visible pathways between home and preschool to her son, Noah. The mother assumed that if the child is not happy, he will express that and the preschool as a collective and the maintenance of a particular engagement as such, was not a priority – making it clear that her primary concern was her child’s well-being and his well-being only. The child in Case 1 (Noah) was the only child to connect the preschool to the curriculum, stating verbally in various ways throughout his interview, that he was there to learn, and that the preschool was the children’s place of learning. Noah identified the verb ‘learn’ as the lead verb for describing the purpose of the preschool. When in the preschool setting, Noah was not concerned with his parents’ role in this part of his life, leaning only on the teachers for the support he needed throughout the day. The mothers in Case 2 (Elliott) and Case 3 (Mason) claimed a high level of involvement, considering themselves to be actively participating in their children’s pedagogical day. However, neither child’s narratives reflected this. Both Elliott and Mason assumed the preschool to be a place where they were kept while their parents had other things to do; both of them identifying ‘play’ as the lead verb for describing the purpose of preschool. The teacher in Case 1 was actively engaged in Noah’s interview process and situation, communication to him both verbally and bodily his position of ownership of both identity and self in the preschool setting. The teacher emphasized this by being present upon my arrival and visibly allowing him space to take command of the situation. This blends with the preschool mission to ensure child well-being through assuming a holistic approach to the child and the mother’s assumption that the preschool will do what is best for the development and well-being (Swedish Agency for Education, Lpfö 98, Citation2010) of the child. In contrast, the teacher’s in Cases 1 and 2 were not present upon my arrival, one of them not making an appearance at all and the other appearing only to greet me and wish me welcome. From the researcher perspective his certainly signals trust, however it is uncertain whether or not this affects the child’s positioning through an absence of teacher’s emotional support.

Finding 2: meaning

The above findings indicate that only one out of the three participating children possessed a clear understanding of the symbiosis of the micro-systems, demonstrating both ownership of self and a sense of belonging (Wenger, Citation2017). This child was Noah and his teacher’s demonstration in the morning of the interview of visibly allowing him the authority to openly assume control of his pending interview situation, also mirrored this sense of self and of belonging; there was a symbiosis between the two of them, and between his story and his mother’s. However, two out of three participating children, Elliott and Mason, lack visible encouragement and nurturing in regard to the relationships and places that pertain to the micro-systems that ultimately form their meso-system. Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) dictates that the more encouraging and nurturing these relationships and places are, the better the child will be able to develop healthily, grow- and develop learning happenings (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Dewey, Citation2012; Feuerverger, Citation2011; Lpfö 98, Citation2010). Within this growth and development lies the child’s ability to learn- and to find meaning in his pedagogical day (Feuerverger, Citation2011), something that when in the preschool setting, contrary to the parents and teachers’ beliefs, was identified as absent from both Elliot’s and Mason’s relationships with their preschool.

Finding 3: practice

In Case 1, Noah’s primary micro-system, his most intimate level of life, was dominating his well-being and sense of self (Wenger, Citation2017) and pushing the other systems to the periphery (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). This was his way of practicing the ownership he possessed of his role in each micro-system, allowing for meaning-making and well-being to exist regardless of which micro-system he found himself in. As cited in Bauer et al. (Citation2012, p. 512) ‘Fivush, Hudson, & Nelson, (Citation1984) noted that when kindergarten children told an interviewer about their day at school, they discriminated events based on location changes throughout the day’. This was not the case with Noah when in the preschool setting. The children from Case 2 and case 3, Elliott and Mason respectively, did however make such discriminations against events, clearly stating that given the option to leave their doings in preschool and go home, they would.

Conclusion

A child’s memory functions is prominent in several phenomena in a child’s systems, including the ‘power of spatial location as a cue to recall’ (Bauer et al., Citation2012) and when I had asked the parents about the application- and use of the preschool’s digital information platform in the family’s life, the mother in Case 1 responded that they look at it together sometimes. However, the mother’s in Case 2 and 3 explicitly state that they are actively engaged in reading the updates, avidly sharing these with their respective children. The children however, when approached about Unikum in their interviews, all claim to never have heard of it. Against this background, it can be suggested that in the case of Elliott and Mason, the amount of spatial–temporal information that is required in order to deliver a narrative in regard to how he perceived his parents role in preschool, is very high (Bauer et al., Citation2012), meaning that Elliott and Mason was not able to reconstruct emotions, understanding or meaning in regard to my inquiry into exploring the different perspectives that interplay. Children aged 4–5 are however, statistically relatively apt at executing such a task and to ‘routinely orient their narratives of personal past events to location or place’ (Bauer et al., Citation2012). So how come Elliott and Mason were unable to do this? In an attempt to map where the stories entered a state of disharmony, a discrepancy between the overall child – adult perspective was identified: it appeared that while the conversations were taking place, they were taking place with the child on the periphery. Here, the difference between having a child’s perspective and taking the child’s perspective (Nilsson et al., Citation2015) became apparent. The latter being the one in which the child is provided a forum to express themselves concerning a particular matter, in this case parent engagement in his preschool. The overarching finding therefore, is that Noah’s mother and teacher carried out these conversations with the child, meaning the child was included rather than informed, whereas with Elliott and Mason the conversations were carried out about the child, meaning the child was informed rather than included (Yngvesson, Citation2019). This results in either (a) a lack of understanding-, or (b) indifference. This qualitative difference between the child- and adult perspectives, imply that in Elliott’s and Mason’s participation in processes concerning themselves, is not enhanced to a level of understanding (Nilsson et al., Citation2015) and placed in a children’s right’s (UN, Citation1989) perspective, Elliott’s and Mason’s comprehension of parent engagement in preschool is assigned but informed (Hart & Risley, Citation1992). The cognitive and experiential capacity of children this age, as well as the level of interpretation of both verbal utterances and body language needed to fully comprehend the children’s opinions and emotions (Nilsson et al., Citation2015) suggest that Elliott and Mason identify themselves as on the periphery of this aspect of their respective lives. From an ideological perspective, this peripheral positioning may seem like a natural development, however whether the two perspectives are better or worse than one another, or whether they are better viewed as different ends on the continuum that is the child – adult relationship, where which perspective you take depends entirely on whether it’s seen from the perspective of the child himself-, the child’s relationship with preschool or the mother’s view of the child (Nilsson et al., Citation2015).

This study sought to identify understanding by applying a narrative approach, and to within the narratives identify where the stories blend and where they contradict. Therefore, these stories were placed in constellations, a version of narrative inquiry that uncovers the children’s, the parents and the teachers’ knowledge and understanding of parent engagement in context (Craig, Citation2007).

A fluid form of investigation that unfolds in a three-dimensional inquiry space, story constellations consist of a flexible matrix of paired narratives that are broadened, burrowed, and restoried over time. The adaptability of this narrative inquiry approach is then made visible through introducing three story constellations separately, then laying sketches of the individual story constellations side-by-side. (Craig, Citation2007, p. 173)

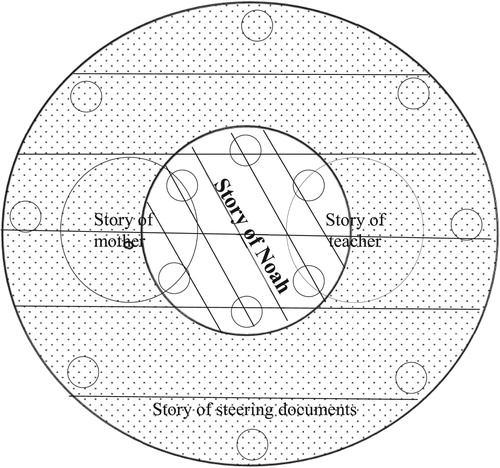

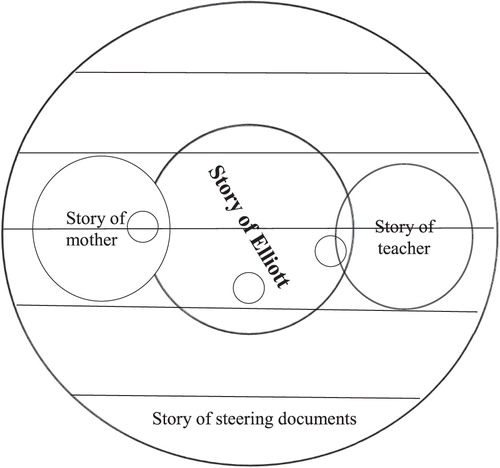

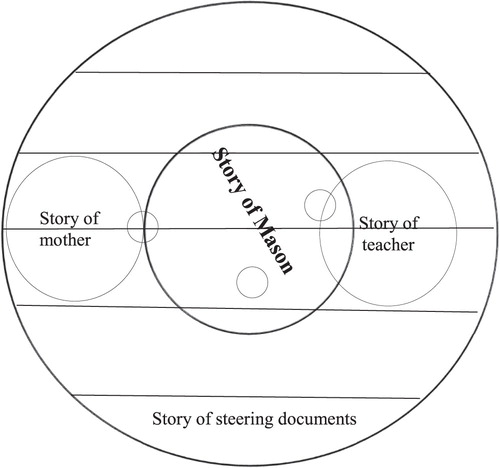

The sketches have their departure point in the child’s perception of engagement whilst in the preschool context (setting). The sketches consist of two layers, the first representing the two micro-systems of home- and preschool in the first (innermost) layer and the meso-system in the second (outermost) layer. The interconnectedness of the circles labelled ‘story of (initials of child)’, ‘story of mother’ and ‘story of teacher’ demonstrate the interconnectedness of the stories and the smaller circles (without text) demonstrates the child’s smaller stories which, which align (or not) across the two systems and stand in relation to the mother- and teacher stories. Thus, the symbiosis between the child-, parent- and teacher understanding of parent engagement on a micro- and meso-level is illuminated. Each sketch is accompanied by a brief explanation of the constellations and with the human voice serving as an instrument of the individual truth, these explanations take the departure point from the child; lifting out their voices from under the white noise of bureaucracy and adult assumption, bringing into daylight children’s narration of experiences and meaning-making. These constellations can thus be viewed as an opportunity to challenge the adult voice, in terms of what they (the adults) know and what they think they know.

As we will see from the sketches, there difference between the child being an active agent in his preschool life or on the periphery, is notable. In these constellations, the smallest circles represent the child’s ‘little stories’, these are the narratives the child delivered throughout the interview which demonstrate understanding and interconnectedness between home and preschool, as well as his understanding of the purpose of preschool; the larger circles labelled ‘story of mother’, ‘story of (name)’ and ‘story of teacher’ are the overall understanding and meaning in terms of steering documents and expectations that the three demonstrated during interviews; the presence or absence of an interlocking between these circles demonstrate the overarching interconnectedness between their understanding, with the vertical lines representing how they align with steering documents and local policies, or not. The diagonal lines in the circle of the child demonstrate the increased harmony between understanding within himself and his sense of position in the triad, regardless of context. The higher the saturation of dots and circles, the greater the harmony. In the event of a non-transparent- or non-overlapping circle, a discrepancy between the three perspectives conception of parental engagement has been identified ().

Figure 1. Story constellation 1: Noah, his mother and his teacher. Adapted from Craig (Citation2007).

Noah tells a story of understanding both the purpose- and task of the preschool. He assumes the preschool to be a place of learning. Noah also assumes the existence of- as well as demonstrates understanding for-, the existence of an engagement between his mother and his teacher. He is not concerend with the details, assuming they will be shared with him upon request. In this constellation we can see that in the meso-system, the overarching role of the steering documents, saturate the relationships; providing all three voices with a forum in which to exercise engagement. In the smaller micro-system(s), Noah’s story aligns with the preschool policies- ideology and curriculum. Furthermore, Noah’s stories are evenly distributed in the micro-system dominated by the mother (home) and the micro-system dominated by the teacher (peschool), indicating that he understands the purpose of the parent engagement as one intended to provide him with a safe environment where he can experience both well-being and a healthy development ().

Figure 2. Story constellation 2: Elliott, his mother and his teacher. Adapted from Craig (Citation2007).

Elliott tells us quite a different story. Elliott’s understanding of preschool does not align with neither steering documents, nor local policies – all of which place emphasis on preschool being a pedagogical institution where children come to learn- and to develop. Thus Elliott assumes preschool to be a place of child-storage and demonstrates indifference in regard to the existence of an engagement between his mother and his teacher. In this constellation we can see that in the meso-system, the overarching role of the steering documents are left bereft of meaning; resulting in a disharmony between the three stories making diffucult the maintenance of a forum in which to exercise engagement. In the smaller micro-system(s), Elliott’s story does not aligns with the preschool policies- ideology and curriculum, nor does it demonstrate an interconnectedness between child- and parent understanding. The mother’s focus is beyond the innermost level of the child’s understanding, centred rather on the interconnectedness between adult – policies and vice versa. Elliott’s stories are unevenly distributed in the micro-system dominated slightly by the mother (home) and with a visible interconnectedness with the teacher (preschool). The overlapping of the mother’s story however, is indicative that Elliott is not included in the dialogue concerning his mother’s parent engagement, rather he is on the periphory of his own story ().

Figure 3. Story constellation 3: Mason, his mother and his teacher. Adapted from Craig (Citation2007).

Mason tells a third story. Mason’s understanding of preschool does not align with neither steering documents, nor local policies. Mason however, is aware of the social and political structural drives that motivate children attending preschool, however has chosen to perceive it only as a place where he can play. Unaware of a greater purpose, Mason, like Elliott, perceives preschool primarily as storage. Mason demonstrates an interconnectedness between his own story and the mother and teacher’s, however no symbiosis between the three, as seen from the perspective of the child, has surfaced in the story constellation. In this constellation we can see that in the meso-system, the overarching role of the steering documents are yet agan left bereft of meaning; resulting even here in a disharmony between the three stories. Hence, making difficult the maintenance of a forum in which to exercise to the child meaningful parent engagement. In the smaller micro-system(s), Mason’s story does not align with the preschool policies- ideology and curriculum, nor does it demonstrate an interconnectedness between child and parent understanding. As we saw in the case with Elliott, the mother’s focus is beyond the innermost level of the child’s understanding, centred rather on the development of understanding between the adult-to-adult and adult-to-policy relatonship. Furthermore, Mason’s stories are unevenly distributed in the micro-system, again dominated slightly by the teacher (preschool) – this time with the mother (home) on the peripheray, indicating that Mason does not posess sufficient understanding regarding parent engagement in preshool for him to value the symbiosis between the two.

Discussion

As we saw earlier in this study the curriculum states that the preschool must strive toward establishing lasting relationships where not only the child’s well-being and development, is central, but where the child is also included in the dialogue concerning the child’s well-being and development (Swedish Agency for Education, Lpfö 98, Citation2010). However, no formal directions are made as to how this is to be achieved. Thus, the strongest support from the data and literature yielded from this study is for the idea that relationships and context matter in combatting existing misaligning of interpretational outcome in regard to policies and steering documents. Meaning that if parents and teachers do not have visible and transparent pathways of communication between them (Hultqvist & Dahlberg, Citation2001; Karlsson & Perälä-Littunen, Citation2017; Simonsson & Markström, Citation2013; PERFAR, Citation2008; Swedish Agency for Education, Citation2010; Tunberger & Sigle-Rushton, Citation2011; Venninen & Purola, Citation2013) the domain between home and preschool will remain one of constant negotiations of understanding (Persson & Tallberg Broman, Citation2017), with the potential result being a continued lack of clarity between expectations and reality.

This study has thus shown that the absence of how in this political text, affects the child’s overall ecological system on four levels. These four levels are the micro-, meso-, exo- and macro-level. In the interest of discussion, these four levels are merged two-and-two, approaching the discussion from the top down as follows, (1) exo- and macro-level and (2) micro- and meso-system. The reason for this is that in order to understand the relationships and impact of these on a micro- and meso-level, we must first lift the contextual issues on a broader level, namely the exo- and the macro-level (Yngvesson, Citation2019). In discussing the findings of the study assumes that both parents and teachers do their best to establish positive pathways with one another, but that in the absence of formal opportunity to deconstruct some of the interpretative issues related to belief- and ideological templates (Olson and Bruner, Citation1996; Yngvesson, Citation2019). This brings us to the first level, where the focus is on the exploration of the three perspectives that interconnect (that of child, parent, teacher). The possible threat of these aforementioned ‘folk psychologies’ is that they serve only to sustain the existing void in both research and practice, where the risk of misinterpretation culminate in parents’ unwillingness to become involved.

As with adults, it can be said of children that their knowledge reflects their understanding of the world (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation1989, Citation1993, Citation1994, Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, Citation1993, Citation1994; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006; Clandinin, Citation1992), thus, the children’s personal epistemologies can be defined as ‘an individuals’ way of knowing and acting arising from their capacities, earlier experiences, and on-going negotiations with the social and brute world, that together shape how they engage with and learn through work activities and interactions’ (Lemon & Garvis, Citation2014, p. 12). Wenger (Citation2017) argues that engagement, imagination and alignment are the three primary factors which create sensations of belonging, which in turn can result in an identity growth. This occurs in different ways, through both time and space (p. 181) which brings us to the second level. We know that the child’s life is dominated by his relationship with his parents and his teachers, as well as affected by the relationship between the aforementioned. Against this background and with the emphasis of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory being on the importance for policy and practice when considering the development and maintenance of necessary bi-directional relationships in ensuring child well-being and healthy development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation1989, Citation1993, Citation1994, Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, Citation1993, Citation1994; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006; Markström & Simonsson, Citation2017; Murray, McFarland-Piazza, & Harrison, Citation2014; Patel & Corter, Citation2013; Persson & Tallberg Broman, Citation2017; Vlasov & Hujala, Citation2017), this level is representative of the inquiry to better understand what parent engagement in preschool means to the child.

The study investigated nine voices and whilst the findings may not translate to preschools in other municipalities, or even in other child-, parent- teacher triads across the same municipality, the results may be symptomatic of an overall void in understanding between what we see on a document and how we interpret that into practice. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory can provide an appropriate conceptual framework through which to interpret processes of parental involvement, engagement and partnership (O’Toole, Citation2017), indicating that a study of similar nature but of grander scale may be widely applicable in helping with similar research not only in Sweden, but in other parts of the world where childhood is ECEC driven.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tina Yngvesson

Tina Elisabeth Yngvesson holds M.Sc. degrees in International Educational Research and International Business. Alongside various international and national research projects in child- and youth sciences, she also works as an educare teacher in a Swedish primary school. Her research interests are early learning- and children's life in preschool, curriculum and policies and parent engagement in children's education. She has also worked with local community groups, focusing heavily on parents in the curriculum versus parents on the periphery. Tina is also part of an overarching municipal organization which is in the early stages of developing pilot projects aimed at increasing participation between home and preschool/school.

Susanne Garvis

Susanne garvis is a professor of Child and Youth studies in the department of Education, Communication and Learning at the University of Gothenburg and a guest professor at the University of Stockholm. She is the leader of the funded Nordic Early Childhood Research Group (NECA) and works on international research grants around early childhood and care. Her research methods include mixed methods, allowing her to work with parents, children, teachers and governmental organizations. She has published numerous books, journal articles and reports within early childhood education with a specific focus on policy, learning and quality.

References

- Alanen, L., Brooker, L., & Mayall, B. (Eds.). (2015). Childhood with Bourdieu. Basingstoke: Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bæck, U. K. (2010). We are the professionals: A study of teachers’ views on parental involvement in school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(3), 323–335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425691003700565

- Battle, J., & Lewis, M. (2002). The increasing significance of class: The relative effects of race and socioeconomic status on academic achievement. Journal of Poverty, 6(2), 21–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J134v06n02_02

- Bauer, P. J., Doydum, A. O., Pathman, T., Larkina, M., Güler, O. E., & Burch, M. (2015). It’s all about location, location, location: Children’s memory for the ‘where’ of personally experienced events. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113(4), 510–522. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.06.007

- Borgonovi, F., & Montt, G. (2012). Parental involvement in selected PISA countries and economies (OECD Education Working Papers No. 73). Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k990rk0jsjj-en

- Bouakaz, L., & Persson, S. (2007). What hinders and what motivates parents’ engagement in school? International Journal about Parents in Education, 1(0), 97–107. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2043/5152

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). The developing ecology of human development: Paradigm lost or paradigm regained. Proceedings from biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Kansas City, MO.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993). The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In R. H. Wozniak & K. Fischer (Eds.), Scientific environments (pp. 3–44). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995a). The bioecological model from a life course perspective: Reflections of a participant observer. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 599–618). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995b). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, Jr., & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619–647). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1993). Heredity, environment and the question ‘How?’ A new theoretical perspective for the 1990s. In R. Plomin & G. E. McClearn (Eds.), Nature, nurture and psychology (pp. 313–324). Washington, DC: American Psychological Society.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualized: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101, 568–586. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. E. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: theoretical Models of human development (Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Qualitative research in social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chong, W. H., & Liem, G. A. D. (2014). Self-related beliefs and their processes: Asian insights. Educational Psychology, 34(5), 529–537. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.916034

- Christenson, S. (2004). The family-school partnership: An opportunity to promote the learning competence of all student. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(4), 454–482. doi: https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.4.454.26995

- Clandinin, D. J. (1992). Narrative and story in teacher education. In T. Russell & H. Munby (Eds.), Teachers and teaching: From classrooms to reflection (pp. 124–137). Philadelphia, PA: The Falmer Press.

- Craig, C. J. (2007). Story constellations: A narrative approach to Contextualizing teachers’ knowledge of school Reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(2), 173–188. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.014

- Crozier, G. (2000). Parents and schools: Partners or protagonists? Stoke-on Trent: Trentham Books.

- Dewey, J. (2012). Education and democracy in the World of Today Schools (1938). Studies in Education, 9(1), 96–100.

- El Nokali, N. E., Bachman, H. J., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2010). Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3), 988–1005. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x

- Emerson, L., Fear, J., Fox, S., & Sanders, E. (2012). Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research. Canberra, Australia: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) for the Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau.

- Emilson, A., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2014). Documentation and communication in Swedish preschools. Early Years, 34(2), 1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2014.880664

- Engin-Demir, C. (2009). Factors influencing the academic achievement of the Turkish urban poor. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(1), 17–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.03.003

- Englund, T. (2010). Questioning the parental right to educational authority – arguments for a pluralist public education system. Education Inquiry, 1(3), 235–258. doi: https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v1i3.21944

- Fantuzzo, J., Tighe, E., & Childs, S. (2000). Family Involvement Questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 367–376. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.367

- Feuerverger, G. (2011). Re-bordering spaces of Trauma: Auto-ethnographic reflections on the immigrant and refugee experience in an inner-city high school in Toronto. International Review of Education, 57(3), 357–375. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-011-9207-y

- Fivush, R., Hudson, J., & Nelson, K. (1984). Children's long-term memory for a novel event: An exploratory study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 30(3), 303–316.

- Flouri, E. (2006). Parental interest in children’s education, children’s self-esteem and locus of control and later educational attainment: Twenty-six-year follow-up of the 1970 British Birth Cohort. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 41–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X52508

- Gilleece, L. (2015). Parental involvement and pupil reading achievement in Ireland: Findings from PIRLS 2011. International Journal of Educational Research, 73, 23–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.08.001

- Goodall, J., and Vorhaus, J. (2011). Review of best practice in parental engagement. London: Department for Education.

- Hakyemez-Paul, S., Pihlaja, P., & Silvennoinen, H. (2018). Parental involvement in Finnish daycare – what do early childhood educators say? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 258–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1442042

- Hanafin, J., & Lynch, A. (2002). Peripheral voices: Parental involvement, social class, and educational disadvantage. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(1), 35–49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690120102845

- Harju-Luukkainen, H., Garvis, S., Bramley, M., Goff, W., Knör, E., Lewadowska, E., … Yngvesson, T. E. (2018). Perspectives on collaboration with parents in ECEC: A content analysis on steering documents in Australia, England Finland, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Germany and Sweden. Springer: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1992). American parenting of language-learning children - persisting differences in family child interactions observed in natural home environments. Developmental Psychology, 28(6), 1096–105. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1096

- Hartman, S. (2005). Det pedagogiska kulturarvet. Traditioner och idéer i svensk undervisningshistoria [ The Pedagogical Cultural heritage. Traditions and ideas in Swedish teaching history]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur (Author’s translation).

- Hayes, N., O’Toole, L., & Halpenny, A. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A guide for students and practitioners in early years education. London: Routledge.

- Hill, N. E., Castellino, D. R., Lansford, J. E., Nowlin, P., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development, 75(5), 1491–1509. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1995). Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record, 95, 310–331.

- Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 3(1), 37–52.

- Hujala, E., Turja, L., Gaspar, M. F., Veisson, M., & Waniganayake, M. (2009). Perspectives of early childhood teachers on parent teacher partnerships in five European countries. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 17(1), 57–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930802689046

- Hultqvist, K., & Dahlberg, G. (2001). Governing the child in the New Millenium. New York: Routledge Falmer.

- Johansson, E., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2006). Play and learning-Inseparable dimensions in preschool practice. Early Child Development and Care, 176(3-4), 441. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500470546

- Karlsson, M., & Perälä-Littunen, S. (2017). Managing the gap - policy and practice of parents in child care and education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 119–122. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1389137

- Lemon, N., & Garvis, S. (2014). Being “In and Out”: Providing voice to early career women in academia. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Löfdahl, A. (2014). Teacher-parent relations and professional strategies – a case study on documentation and talk about documentation in a Swedish preschool. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 39(3), 103–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911403900313

- Emerson, L., Fear, J., Fox, S., & Sanders, E. (2012). Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research. Canberra, Australia: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) for the Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau.

- Löfgren, H. (2015). A noisy silence about care: Swedish preschool teachers’ talk about documentation. Early Years, 36(1), 1–13.

- Löfdahl, A., and Hägglund, S., (2006) Power and participation: Social representations among children in pre-school. Social Psychology of Education, 9(2), 179–194.

- Markström, A.-M. (2013a). Children’s perspectives on the relations between home and school. International Journal about Parents in Education, 7(1), 43–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12114

- Markström, A.-M. (2013b). Garderoben som sted for samar- beid og forhandlingen mellom hjem og barnehage. In E. Foss (Ed.), Til barnas beste. Veier til omsorg og lek, læring og danning (pp. 218–239). Oslo: Gyldendals Forlag.

- Markström, A. M., & Simonsson, M. (2017). Introduction to preschool: Strategies for managing the gap between home and preschool. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 179–188. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1337464

- Murray, E., McFarland-Piazza, L., & Harrison, L. J. (2014). Changing patterns of parent–teacher communication and parent involvement from preschool to school. Early Child Development and Care, 185(7), 1031–1052. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.975223

- Nilsson, S., Björkman, B., Almqvist, A. L., Almqvist, L., Björk-Willén, P., Donohue, D., … Hvit, S. (2015). Children’s voices – differentiating a child perspective from a child’s perspective. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 18(3), 162–168. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2013.801529

- Nisbett, R. E., Aronson, J., Blair, C., Dickens, W., Flynn, J., Halpern, D. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2012). Intelligence: New findings and theoretical developments. American Psychologist, 67(2), 130–159.

- Okpala, C. O., Okpala, A. O., & Smith, F. E. (2001). Parental involvement, instructional expenditures, family socioeconomic attributes, and student achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 95(2), 110–115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670109596579

- Olson, D. R., & Bruner, J. S. (1996). Folk psychology and folk pedagogies. In D. R. Olson and N. Torrance (Eds.), The handbook of education and human development (pp. 9–27). Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2012). Research brief: Parental and community engagement matters. Encouraging Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC). Starting Strong III Toolbox.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). Starting strong IV: Monitoring quality in early childhood education and care. Washington, DC: Author.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2017). Starting strong 2017: Key OECD indicators on early childhood education and care. Washington, DC: Author.

- Osgood, J. (2012). Narratives from the nursery: Negotiating professional identities in early childhood. London: Routlegde.

- O’Toole, L. (2017). A bioecological perspective on parental involvement in children’s education. Conference Proceedings: The Future of Education, 7th Edition, 385–389.

- Patel, S., & Corter, C. (2012). Building capacity for parent involvement through school-based preschool services. Early Child Development and Care, 183(7), 1–24.

- Persson, S., & Tallberg Broman, I. (2017). Early childhood education and care as a historically located place – the significance for parental cooperation and the professional assignment. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 189–199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1352440

- Phillipson, S., & Phillipson, S. N. (2012). Academic expectations, belief of ability, and involvement by parents as predictors of child achievement: A cross cultural comparison. Educational Psychology, 27(3), 329–348.

- Phillipson, S. & Phillipson, S. N. (2017). Generalizability in the mediation effects of parental expectations on children's cognitive ability and self-concept. Child Family Studies, 26, 3388–3400. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0836-z

- Population Europé Resource Finder and Archive. (2008). Family policy: Sweden. Retrieved from https://www.perfar.eu/policy/family-children/sweden

- Sheldon, S. B. (2007). Improving student attendance with school, family, and community partnerships. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(5), 267–275. doi: https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.100.5.267-275

- Sheridan, S., Williams, P., & Sandberg, A. (2013). Systematic quality-work in preschool. International Journal Of Early Childhood, 45(1), 123–150. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-012-0076-8

- Sibley, E., & Dearing, E. (2014). Family educational involvement and child achievement in early elementary school for American-born and immigrant families. Psychology in the Schools, 51(8), 814–831. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21784

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2010). Learning in the home and at school: How working-class children ‘succeed against the odds’. British Educational Research Journal, 36(3), 463–482.

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A metanalytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453.

- Simonsson, M., & Markström, A. M. (2013). The parent-teacher conference as a task and tool in the pre-school teachers' professional practice in interaction with parents. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 6(10), 1–18.

- Swedish Agency for Education [Skolverket]. (2010). Education Act 2010:800.

- Tan, E., & Goldberg, W. A. (2009). Parental school involvement in relation to children’s grades and adaptation to school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(4), 442–453. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.023

- Tunberger, P., & Sigle-Rushton, W. (2011). Continuity and change in Swedish family policy reforms. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(3), 225–237. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710395048

- United Nations (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Geneva: UN.

- Uusimäki, L., Yngvesson, T. E., Garvis, S., & Harju-Luukkainen, H. (2019). Parental involvement in ECEC in Finland and Sweden. Victoria, Australia: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wenger, E. (2017). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Widding, G., & Berge, B. (2014) Teacher’s and parent’s experiences of using parents as resources in Swedish primary Education. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 1587–1593. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.439

- Venninen, T., & Purola, K. (2013). Educators’ views on parent participation on three different identified levels. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 2(1), 48–62.

- Vincent, C., & Ball, S. (2006). Childcare, choice and class practices: Middle-cross parents and their children. London: Routledge.

- Vlasov, J., and Hujala, E. (2017). Parent-teacher cooperation in early childhood education – directors' views to changes in the USA, Russia, and Finland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 732–746. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356536

- Yamamoto, Y., & Holloway, S. (2010). Parental expectations and children’s academic performance in sociocultural context. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 189–214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9121-z

- Yang, Y. (2003). Measuring socioeconomic status and its effects at individual and collective levels: A cross-country comparison. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. Print. Göteborg Studies in Educational Sciences, 193.

- Yngvesson, T. E. (2019). Parent engagement in Swedish preschools: A narrative inquiry through the conceptual lens of proximal processes (Master thesis ). University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.