ABSTRACT

We investigated health-related quality of life in preterm children in association with birth weight, breastfeeding and maternal emotional state. A cross-sectional study was carried out involving 97 mothers of 2-year-old children born below 2500 g. Participants completed the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory and a comprehensive psychological interview. Birth weight and chronic neonatal morbidities were not significant predictors of quality of life at 2 years. However, breastfeeding and positive maternal emotional state were important protective factors to the prospective quality of life of preterm children. Retrospectively, calm mothers reported their children more positively comparing to anxious mothers both during their pregnancy and after birth. As protective factors, the positive maternal emotional state before and after childbirth and breastfeeding are more crucial in the development of quality of life at 2 years than biological factors.

Introduction

Preterm birth is a serious medical issue globally, which complications carry the risk of cognitive and social difficulties, neurosensory deficits and psychiatry disorders (Doyle & Anderson, Citation2010; Vederhus, Markestad, Eide, Graue, & Halvorsen, Citation2010). The high prevalence of dysfunctions (Aylward, Citation2003) results in negative outcomes in the areas of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and social functioning (Hack, Cartar, Schluchter, Klein, & Forrest, Citation2007; Saigal, Citation2013).

The morbidity of prematurity is associated with the short gestational period (Korvenranta et al., Citation2009), low birth weight (Platt et al., Citation2007) and early complications (Roze et al., Citation2009). Infants born under 1500 g and before the 32-gestational week are at the highest risk regarding several developmental problems such as visual impairment (Bodeau-Livinec et al., Citation2007), hearing loss (Cristobal & Oghalai, Citation2008), cognitive impairment (Woodward et al., Citation2009), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Sucksdorff et al., Citation2015) or epilepsy (Pisani et al., Citation2004). However, recognizing these diseases alone is not enough to understand their impact and burden on children and their families. For this reason, more comprehensive studies are crucial to explore these issues, which focuses on other aspects of these conditions, such as their impact on everyday life. Such aspect is the health-related quality of life, which refers to one’s ability to tend to the tasks of everyday life, which is a combination of physical, emotional and social well-being (Hays & Reeve, Citation2010).

Prematurity and its subsequent complications impact quality of life through difficulties in everyday life, however, this relationship is highly complex. A systematic review of 15 studies found that preterm children who were born with severe neural deficits reported similar quality of life as young adults than those, who were born at the end of a full-time pregnancy. Children and adolescents born prematurely, however, reported lower quality of life than the control group. Moreover, parental reports showed significantly lower quality of life in toddlers, school-aged children and adolescents compared to the preterm children’s self-reports and to those who were born in time (Chien, Chou, Ko, & Lee, Citation2006; Lunenburg et al., Citation2013; Rautava et al., Citation2009; Zwicker & Harris, Citation2008). Based on these inconsistent results, quality of life seems to vary throughout development, thus it is informative to measure it from the earliest ages.

In early childhood, the role of mothers, as main attachment figures are crucial in the development of emotional and social functions of children (Malatesta, Culver, Tesman, & Shepard, Citation1989). Several studies found the maternal emotional state to be critically important for the mental health of both their own and their children not only after birth but during the pregnancy as well (Sandman, Davis, Buss, & Glynn, Citation2011). Another important aspect at this age is breastfeeding, which is essential for the development of attachment between the mother and infant through the ritual of feeding, eye contact and direct skin-to-skin contact (Fergusson & Woodward, Citation1999). The beneficial effects of breastfeeding are well-researched, especially on later physiological and cognitive development (Whitehouse, Robinson, Li, & Oddy, Citation2011), although only a few studies explored its impact on emotional development and quality of life specifically in early childhood.

Our goal was to assess the health-related quality of life among preterm children at the age of 2 and its associations with birth weight, as well as with other influencing factors from both the mother and child. We measured crucial aspects of this early period, such as maternal emotional state (both in the period of pregnancy and after birth), duration and method of breastfeeding, chronic morbidities and behavioural characteristics of the infants, retrospectively.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our research was approved by the Hungarian Medical Research Council (33176-2/2017/EKU) following the ethical principles of the WMA Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample

Data collection was carried out between October 2016 and August 2017 at the Pediatric Clinic of University of Debrecen. The examination took place within the psychology outpatient care of the Pediatric Psychology and Psychosomatic Unit, where 97 mothers of premature and/or low-birth-weight children were asked to participate in the study. The children were assessed at 2 years old.

In our research, we used birth weight to divide children into groups based on their immaturity and the level of biological vulnerability. Low birth weight refers to infants born below 2500 g, which can be further divided into three subgroups based on the 1961 definition of WHO (WHO, Citation1961): low birth weight (1500–2499 g) – LBW; very low birth weight (1000–1499 g) – VLBW; extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) – ELBW. Using this classification, we sorted the children of our sample into three groups: LBW (n = 23), VLBW (n = 35) and ELBW (n = 39) ().

Table 1. Characteristics of pregnancy, childbirth and development.

Measures

Health-related quality of life questionnaire

As a dependent variable, Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured by the generic module of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL; Varni, Citation1998), which is a proxy questionnaire for parents of 2–4 years old children. PedsQL measures, four areas of functioning: physical functioning (eight items, such as running, lifting heavy objects, sports), emotional functioning (five items, such as anger, fear, sadness), social functioning (five items, such as playing with other children) and school functioning (three items, such as the inability of doing something like the other children). Mothers were asked to rate on a 5-points Likert-scale, how difficult was for their children the particular task (0 = never; 1 = mostly never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = often; 4 = always). In this age group, school functioning refers to the period before kindergarten, however, only 12% of the sample was frequently among other children, therefore, this scale was omitted from the statistical analysis.

Data collection from final reports

Retrospective analysis of neonatal final reports was used to determine the existence of chronic neonatal morbidities, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), etc.

Psychological interview

Items were utilized from the structured questionnaire used in the Hungarian adaptation of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley, Citation2006; Hungarian adaptation: Kő, Rózsa, Mészáros, Kálózi-Szabó, & Nagy, Citation2017). Data were gathered retrospectively about the period from conception until the time of examination. We assessed the course of pregnancy (e.g. with or without any problems) and the circumstances of birth (e.g. vias naturales, section caesarea). Other independent variables we used in the analyses were the following:

Breastfeeding

As part of the psychological anamnesis, we gathered information about the mothers’ ability to breastfeed her new-born. In case of ‘yes’, we used open questions to assess the time and duration of breastfeeding and structured questions to assess the way the new-born fed (e.g. ‘with a good technique’ or ‘frequent swallowing and sucking problems’).

Behavioural characteristics of infants

Behavioural characteristics were also explored retrospectively. A list containing both positive and negative characteristics was presented to the mothers (e.g. weepy, well-adjusted, calm, etc.) and binary coding was used to gather a list of dominant characteristics. Then two scales were converted based on the list: one contained the positive characteristics of the infant (e.g. calm, good sleeper, well-adjusting or easy), the other, on the other hand, contained the negative characteristics such as weepy, peevish, bad sleeper or colicky. These scales were used in the statistical analysis.

Predominant maternal emotional state

The predominant emotional state of the mothers was also assessed by structured questions retrospectively. For example, the following options were available to choose: ‘collected, optimist, suspenseful’ or ‘emotionally unstable, ambivalent’. Mothers were asked to retrospectively rate their dominant emotional state for both in the period of pregnancy and after childbirth.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics v23 was used for statistical analysis. General characteristics of the sample were analysed by descriptive statistics. After data collection, the normality of the sample was assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Chi-square test. The results indicated paranormal distribution in most of our variables, so non-parametric statistical tests were used for analysis. Mann–Whitney U-test test was used to measure the differences between two groups (e.g. breastfed-not breastfed), whereas Kruskal–Wallis was utilized to compare two or more groups regarding the independent variables (e.g. predominant maternal state). Finally, Spearman rank correlation test was used to measure the relationship between continuous and ordinal variables (e.g. birth weight, HRQoL, behavioural characteristics of infants).

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The mean birth weight of toddlers participating in the study (n = 97) was between 330 and 2490 g (M = 1246.81; SD = 531.25). The mean gestational age also was low (M = 30.13; SD = 3.7), as almost all the low-birth-weight sample was born prematurely. The mean age of children was 25.8 mo. (SD = 2.04) during the examination. The mean age at birth of mothers was 29 years (M = 29.45 ;SD = 4.91) and 11 women (11.35%) reached the age of 35 among them. On average, infants and mothers spent 46 days in the hospital after birth (M = 46.17; SD = 28.23) ().

Biological factors and health-related quality of life at 2 years

The mean scores of the function areas examined by PedsQL were the following: social functioning was rated as highest (M = 87.47; SD = 15.5), followed by physical functioning (M = 83.14; SD = 15.57), whereas mothers evaluated the lowest quality of life in emotional functioning (M = 75.72; SD = 15.34). The most frequently chosen difficulties were anger (35%), fear (19%) and sleeping problems (14%) based on parental reports. The mean score of quality of life was 82.26 (SD = 11.99).

No significant association was found between quality of life and the most frequent neonatal morbidities such as IVH (p = 0.699; χ2 = 0.715), ROP (p = 0.477; χ2 = 1.481), PVL (p = 0.52; U = 30.0), NEC (p = 0.505; U = 109.0), intrauterine hypoxia (p = 0.132; U = 207.0) or intrauterine asphyxia (p = 0.509; U = 29.5). However, mothers reported significantly lower quality of life in preterm infants with BPD (p = 0.025; U = 443.5). The distribution of neonatal morbidities in the sample is shown in .

Table 2. Distribution of chronic neonatal morbidities.

We found no significant differences in quality of life between birth-weight groups at 2 years. The Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant association between birth weight and quality of life at 2 years (p = 0.180; χ2 = 3.431).

We found gender differences only in emotional functioning (p = 0.039; U = 878.00). Mothers reported significantly more emotional problems in boys compared to girls. No significant differences were found between boys and girls in social functioning (p = 0.628; U = 1096.5) and physical functioning (p = 0.962; U = 1154.5).

Behavioural characteristics of infants and emotional functioning at 2 years

In addition to gender differences, emotional problems were also associated with the behavioural characteristics of the infants. Mothers described their infants the most frequently as ‘colicky’ (30%) and ‘irritated’ (17%) as negative characteristics, on the other hand, ‘calm’ (62%) and ‘good sleeper’ (49%) were among the most frequently chosen positive characteristics. In statistical analysis, we generated two scales based on the reported binary-coded list of characteristics. The two scales included the number of positive characteristics (such as calm, good sleeper, adaptable and easy to take care of) and negative characteristics (such as irritated, weepy, bad sleeper, has a loss of appetite or colicky), respectively. Spearman rank correlation showed a significant relationship between emotional functioning and both the number of positive and negative characteristics (). More positive behavioural characteristics significantly correlated with higher emotional functioning (p = 0.033; r = 0.216). Based on the coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.046), positive behavioural characteristics explain 4.6% of variance in emotional functioning at 2 years. On the other hand, a stronger, negative correlation was found in connection with the number of negative characteristics (p = 0.002; r = −0.313; R2 = 0.097), which provides a 9.7% explanatory power. Moreover, the higher number of negative behavioural characteristics significantly correlated with the overall quality of life (p = 0.004; r = −0.291).

Table 3. Quality of life at 2 years in association with behavioural characteristics of infants.

Breastfeeding and quality of life

A positive but weak correlation was found between the duration of breastfeeding and quality of life (p = 0.016; r = 0.244), indicating that mothers reported higher overall quality of life in their children in case of longer duration of breastfeeding. Nonetheless, almost half of mothers (43%; <1000 g: 73%; 1000–1500 g: 34%; 1500–2500 g: 13%) was unable to breastfeed after birth. The mean duration of breastfeeding was 6.58 months (SD = 8.08).

The association between quality of life and potential non-nutritive sucking habits (i.e. using a lazy method or having swallowing and sucking difficulties) was also assessed. These problems occurred in 44% of the sample. No significant connection was found between quality of life and sucking habits (p = 0.433; χ2 = 1.672), however, there were marginal but significant differences in overall quality of life in comparison with mother who could not breastfeed their infants (p = 0.05; U = 891.5). Similarly, no significant association was found between each of the function areas and sucking habits, however, the tendency was also similar between the groups of those who were and were not breastfed (). Based on the mean scores of quality of life, breastfeeding mothers tendentially reported higher overall quality of life in their children at 2 years, even if the experience problems in sucking habits, compared to those who were unable to breastfeed.

Table 4. Associations between breastfeeding and quality of life.

Maternal emotional state and quality of life at 2 years

Significant associations were found between the quality of life of preterm children at 2 years and the retrospectively assessed predominant maternal emotional state both during pregnancy (p = 0.007; χ2 = 10.059) and after birth (p < 0.01; χ2 = 15.209) (). Those mothers, who retrospectively described themselves as balanced, positive, excited during their pregnancy, characterized their children more positively and reported significantly fewer difficulties in physical (p = 0.013; χ2 = 8.688) and social (p = 0.02; χ2 = 12.654) functioning compared to conflicted and anxious mothers. Reversely, anxious and nervous or emotionally unstable mothers reported more difficulties in physical and social functioning in their children at 2 years. After childbirth, we also found this significant association in each area of functioning: physical (p = 0.012; χ2 = 8.905), emotional (p = 0.006; χ2 = 10.333) and social (p = 0.024; χ2 = 7.462) functioning.

Table 5. Associations between predominant maternal emotional state and reported quality of life at 2 years.

Discussion

Biological factors and health-related quality of life at 2 years

In our examination, mothers reported the fewest problems in social functioning at 2 years, thus the preterm children seem to have no difficulties at 2 years regarding social skills in social activities such as playing with other children. They experienced more problems in physical functioning (e.g. walking or running, lifting heavy objects and putting away their toys), which can be explained by the delay or deficit of gross motor skills. These difficulties are more frequent in preterm children due to their prematurity (Ramachandran & Dutta, Citation2015). Finally, mothers reported the most problems in emotional functioning. Dealing with negative emotions, such as anger or fear and bad sleeping were the most problematic for children according to their mothers.

It must be noted that many studies examining preterm children found correlations between lower birth weight and lower developmental quotients in developmental areas such as gross or fine motor skills or social skills even at 2 years (Kenyhercz & Nagy, Citation2017; Potijk, de Winter, Bos, Kerstjens, & Reijneveld, Citation2012; Talge et al., Citation2010). However, our results suggest that birth weight is not a significant predictor for the quality of life reported by mothers. Regarding the most common neonatal morbidities in preterm infants, we found significant associations exclusively between bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and quality of life at 2 years. Mothers of children with BPD reported significantly lower overall quality of life compared to their healthy peers. Thus, children with BPD may be at risk of lower quality of life at later ages as well.

After the examination of gender differences, we found that boys were reported as having more emotional problems, especially in dealing with the emotions of anger and frustration. A meta-analysis of 166 studies reported similar findings in gender differences, where girls had more positive emotions and internalizing symptoms (e.g. anxiety, fear) compared to boys, who showed rather externalizing symptoms (e.g. anger and frustration) (Chaplin & Aldao, Citation2013). Furthermore, a study found that high maternal prenatal anxiety is a high-risk factor of emotional difficulties in boys, compared to girls at 4 years (O’Connor, Heron, Golding, Beveridge, & Glover, Citation2002). High-risk pregnancy and preterm birth are also linked to higher anxiety levels of mothers (Alder, Fink, Bitzer, Hösli, & Holzgreve, Citation2007).

Behavioural characteristics of infants and emotional functioning at 2 years

Examining the behavioural characteristics of the infants, we found a significant correlation with emotional difficulties based on maternal reports. In the case of negative characteristics, mothers reported their babies as ‘colicky’ and ‘irritated’ and they used calm’ and good sleeper’ the most as positive characteristics. Mothers, who retrospectively used more negative behavioural characteristics to describe their babies, reported significantly more emotional problems in their children at 2 years. Reversely, the same strong correlation was found between the number of positive behavioural characteristics and higher quality of life in physical and emotional functioning. These reported characteristics can be interpreted as ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’ based on the theory of Thomas and Chess (Thomas & Chess, Citation1977). Several studies found positive correlation between easy temperament and higher levels of social, personality and cognitive development in toddlers and small children, whereas difficult temperament was linked to higher rates of behavioural and emotional difficulties (Abulizi, Pryor, Michel, van der Waerden, & EDEN Mother-Child Cohort Study Group Citation2017; Stams, Juffer, & van IJzendoorn, Citation2002). In our study, we found significant correlation in both ways between ‘temperament’ and physical and emotional functioning in 2-year-old children.

Breastfeeding and quality of life

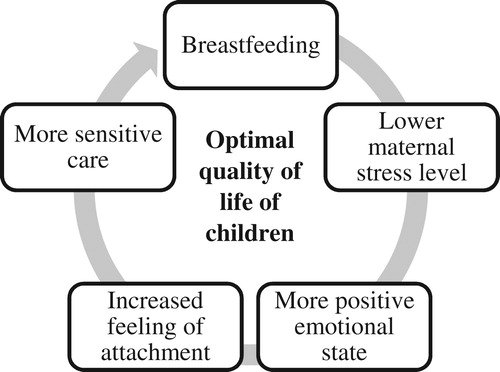

In the literature, the beneficial effects of breastfeeding are widely accepted. Breast milk is an essential source of nutrients as it is rich in essential fatty acids, vitamins, minerals and amino acids, which are fundamental for both cognitive functioning and speech development (Whitehouse et al., Citation2011). A meta-analysis showed a negative correlation between the duration of breastfeeding and lower risks of acute respiratory and ear infections, asthma, obesity and type 1 and 2 diabetes, so a variety of psychosomatic diseases (Ip et al., Citation2007). The increased production of prolactin and oxytocin during breastfeeding lowers the stress levels of the mothers and strengthens the attachment toward the baby (Uauy & de Andraca, Citation1995). The positive emotional state and the increased feeling of attachment further contribute to a more sensitive care from the mothers (DeWitt et al., Citation1997), thereby to a smoother breastfeeding process, which again lowers the stress level of the mothers and helps achieve a more positive emotional state and so on (). This process, therefore, functions as a self-reinforcing cycle, which may promote both the mother’s and baby’s health.

Based on the findings of our study and the literature we can conclude that mothers, who breastfeed their babies, reported a significantly more positive emotional state for themselves and higher quality of life for their 2-year-old children regardless of any difficulties in breastfeeding. They experienced fewer physical, emotional and social difficulties among their children compared to mothers, who for some reason, were unable to breastfeed their new-borns.

We also confirmed the importance of the maternal mental health in the optimal quality of life in children. During infancy, one aspect of maternal functioning is the mirroring of emotions to the children (Gergely, Citation1996), which may bring difficulties for an emotionally less stable, depressed and worrisome mother. Several studies of the last decades examined the effects of maternal emotional state not only on the foetus during pregnancy but on the baby after giving birth as well (Sandman et al., Citation2011). Our findings support this concept that maternal emotional state before and after childbirth has a vital role in the development of quality of life in children.

Conclusions

In our study, we found the maternal emotional state before and after childbirth to be a more important aspect in the development of quality of life in early childhood, as opposed to birth weight or other biological factors. Moreover, breastfeeding seems to be an essential protective factor for the mother–child bond as well.

Considering our findings, we find it important to help mothers during the early days of motherhood regarding breastfeeding. Moreover, implementing interventions like the ‘golden hour’ protocol or the Kangaroo care after childbirth are also vital, since the early hours in life and skin-to-skin contact are critical in the later development of attachment (Harriman, Citation2018) and quality of life. Furthermore, it may also have an impact on the maternal mental health. The use of these early interventions seems crucial in the later development of at-risk premature children. In addition to sooner recovery after birth, they may also have an indirect impact on the later quality of life in both children and their parents.

The emotional support of mothers and fathers after premature birth should be also an important intervention during the early years, not only for their mental health and quality of life but their children’s as well. We recommend utilizing the help of mental health professionals, clinical and health psychologists in paediatric clinics and obstetric and new-born care units in order to provide support for parents of premature children.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is the small sample size. In order to overcome this limit, we pursue the involvement of more children and parents to confirm these preliminary findings. Beyond the detailed exploration of the breastfeeding process, we set out to examine the quality of life of children, who were exclusively fed with formula and to carry out a comparative study. Moreover, more information might be gathered by carrying out a longitudinal follow-up study, in which the development of emotional, social and cognitive functioning can be assessed regarding the ways of feeding in the early years, from infancy to adolescence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the children and parents for their participation and interest in this study. We are grateful to our colleagues in the DE KK Pediatric Clinic and the Department of Neonatology for their contribution in data collection and assistance in pre-processing self-report data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Flóra Kenyhercz

Flóra Kenyhercz is a health-psychologist and doctoral student at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Debrecen. Her research focus is on the quality of life, mental health, and psychomotor and cognitive development of preterm children.

Szabolcs Kató

Szabolcs Kató is a health-psychologist and doctoral student at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Debrecen. His research focus is on the quality of life and mental health of children with inflammatory bowel disease.

Beáta Erika Nagy

Beáta Erika Nagy is a clinical child psychologist, psychotherapist and professor of child psychology at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Debrecen. Her research focus is on the psychomotor and cognitive development of preterm children and the mental health of children with chronic diseases.

References

- Abulizi, X., Pryor, L., Michel, G., van der Waerden, J., & EDEN Mother-Child Cohort Study Group. (2017). Temperament in infancy and behavioral and emotional problems at age 5.5: The EDEN mother-child cohort. Plos One, 12(2), e0171971. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171971. eCollection 2017.

- Alder, J., Fink, N., Bitzer, J., Hösli, I., & Holzgreve, W. (2007). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 20(3), 189–209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050701209560

- Aylward, G. P. (2003). Neonatology, prematurity, NICU, and developmental issues. In M. C. Roberts (Ed.), Handbook of pediatric psychology (pp. 253–268). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development (3rd ed.). Administration manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment.

- Bodeau-Livinec, F., Surman, G., Kaminski, M., Wilkinson, A., Ancel, P., & Kurinczuk, J. (2007). Recent trends in visual impairment and blindness in the UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92, 1099–1104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.117416

- Chaplin, M. T., & Aldao, A. (2013). Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 735–765. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030737

- Chien, L. Y., Chou, Y. H., Ko, Y. L., & Lee, C. F. (2006). Health-related quality of life among 3–4-year-old children born with very low birthweight. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56, 9–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03974.x

- Cristobal, R., & Oghalai, J. (2008). Hearing loss in children with very low birth weight: Current review of epidemiology and pathophysiology. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 93, F462–F468. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.124214

- DeWitt, S. J., Sparks, J. W., Swank, P. B., Smith, K., Denson, S. E., & Landry, S. H. (1997). Physical growth of low birthweight infants in the first year of life: Impact of maternal behaviors. Early Human Development, 47, 19–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-3782(96)01757-4

- Doyle, L. W., & Anderson, P. J. (2010). Adult outcome of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics, 126(2), 342–351. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0710

- Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (1999). Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13, 144–157. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.x

- Gergely, G. (1996). ‘Hoppá!’, avagy az eszmélkedés lélektana: a szociális tükrözés szerepe az öntudat és az önkontroll kialakulásában. Pszichológia, 16, 361–382.

- Hack, M., Cartar, L., Schluchter, M., Klein, N., & Forrest, C. B. (2007). Self-perceived health, functioning and well-being of very low birth weight infants at age 20 years. Journal of Pediatrics, 151(6), 635–641. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.063

- Harriman, T. L. (2018). Golden hour protocol for preterm infants. A quality improvement project. Advances in Neonatal Care, 18(6), 462–470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000554

- Hays, R. D., & Reeve, B. B. (2010). Measurement and modeling of health-related quality of life. In J. Killewo, H. K. Heggenhougen, & S. R. Quah (Eds.), Epidemiology and demography in public health (pp. 195–205). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Ip, S., Chung, M., Raman, G., Chew, P., Magula, N., DeVine, D., … Lau, J. (2007). Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 153, 1–186.

- Kenyhercz, F., & Nagy, B. E. (2017). Examination of psychomotor development in relation to social-environmental factors in preterm children at 2 years old. Orvosi Hetilap, 158(1), 31–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1556/650.2017.30628

- Kő, N., Rózsa, S., Mészáros, A., Kálózi-Szabó, C., & Nagy, B. (2017). A Bayley-III Csecsemő és Kisgyermek Skálák magyar kézikönyve: hazai tapasztalatok, vizsgálati eredmények és normák. Budapest: OS Hungary Tesztfejlesztő Kft.

- Korvenranta, E., Lehtonen, L., Peltola, M., Häkkinen, U., Andersson, S., Gissler, M., … Linna, M. (2009). Morbidities and hospital resource use during the first 3 years of life among very preterm infants. Pediatrics, 124, 128–134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1378

- Lunenburg, A. M., van der Pal, S., Van Dommelen, P., van der Pal-de Bruin, K. M., Bennebroek Gravenhorst, J., & Verrips, G. H. (2013). Changes in quality of life into adulthood after very preterm birth and/or very low birth weight in the Netherlands. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-51

- Malatesta, C. Z., Culver, C., Tesman, J. R., & Shepard, B. (1989). The development of emotion expression during the first two years of life. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 54(219), 1–2.

- O’Connor, T. G., Heron, J., Golding, J., Beveridge, M., & Glover, V. (2002). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(6), 502–508. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.6.502

- Pisani, F., Leali, L., Parmigiani, S., Squarcia, A., Tanzi, S., Volante, E., & Bevilacqua, G. (2004). Neonatal seizures in preterm infants: Clinical outcome and relationship with subsequent epilepsy. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 16(Suppl. 2), 51–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/jmf.16.2.51.53

- Platt, M. J., Cans, C., Johnson, A., Surman, G., Topp, M., Torrioli, M. G., & Krageloh-Mann, I. (2007). Trends in cerebral palsy among infants of very low birthweight (<1500 g) or born prematurely (<32 weeks) in 16 European centres: A database study. Lancet, 369, 43–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60030-0

- Potijk, M. R., de Winter, A. F., Bos, A. F., Kerstjens, J. M., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2012). Higher rates of behavioural and emotional problems at preschool age in children born moderately preterm. Archives of Disease in Childhoodrch, 97(2), 112–117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2011.300131

- Ramachandran, S., & Dutta, S. (2015). Developmental screening tools for motor developmental delay in high risk preterm infants. Journal of Nepal Pediatric Society, 35(2), 162–167. doi: https://doi.org/10.3126/jnps.v35i2.12954

- Rautava, L., Häkkinen, U., Korvenranta, E., Andersson, S., Gissler, M., Hallman, M., … Lehtonen, L. (2009). Health-related quality of life in 5-year-old very low birth weight infants. The Journal of Pediatrics, 155, 338–343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.03.061

- Roze, E., Van Braeckel, K., Veere, C., Maathuis, C., Martijn, A., & Bos, A. (2009). Functional outcome at school age of preterm infants with periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics, 123, 1493–1500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1919

- Saigal, S. (2013). Quality of life of former premature infants during adolescence and beyond. Early Human Development, 89(4), 209–213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.01.012

- Sandman, C. A., Davis, E. P., Buss, C., & Glynn, L. M. (2011). Prenatal programming of human neurological function. International Journal of Peptides, 1–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/837596

- Stams, G. J., Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2002). Maternal sensitivity, infant attachment, and temperament in early childhood predict adjustment in middle childhood: The case of adopted children and their biologically unrelated parents. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 806–821. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.806

- Sucksdorff, M., Lehtonen, L., Chudala, R., Suominen, A., Joelsson, P., Gissler, M., & Sourander, A. (2015). Preterm birth and poor fetal growth as risk factors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 136(3), e599–e608. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1043

- Talge, N., Holzman, C., Wang, J., Lucia, V., Gardiner, J., & Breslau, N. (2010). Late-preterm birth and its association with cognitive and socioemotional outcomes at 6 years of age. Pediatrics, 126(6), 1124–1131. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1536

- Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

- Uauy, R., & de Andraca, I. (1995). Human milk and breast feeding for optimal mental development. The Journal of Nutrition, 125, 2278–2280. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/125.suppl_8.2278S

- Varni, W. J. (1998). The PedsQL. Measurement model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory. PedsMetrics, Quantifying the Qualitative. Medical Care, 37(2), 126–139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003

- Vederhus, B., Markestad, T., Eide, G., Graue, M., & Halvorsen, T. (2010). Health related quality of life after extremely preterm birth: A matched controlled cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 53–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-53

- Whitehouse, A. J., Robinson, M., Li, J., & Oddy, W. H. (2011). Duration of breastfeeding and language ability in middle childhood. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 25, 44–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01161.x

- WHO. (1961). The work of WHO 1961. Official records of the World Health Organization, No. 114. Geneva.

- Woodward, L. J., Moor, S., Hood, K. M., Champion, P. R., Foster-Cohen, S., Inder, T. E., & Austin, N. C. (2009). Very preterm children show impairments across multiple neurodevelopmental domains by age 4 years. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 94, F339–F344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.146282

- Zwicker, G. J., & Harris, R. S. (2008). Quality of life of formerly preterm and very low birth weight infants from preschool age to adulthood: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 121(2), 366–376. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0169